Abstract

In this paper, a low-damage flexible drum-shaped threshing element is designed to address the stringent requirements for seed harvesting, specifically targeting the issues of high seed breakage rates, low threshing rates, and elevated entrainment loss rates during the mechanized harvesting process of rice seed propagation. Initially, a mathematical model was developed to determine the maximum normal impact force exerted by the threshing elements on rice seeds throughout the threshing process, derived from a comprehensive mechanical analysis. Subsequently, experimental research was conducted to investigate the physical properties of rice, leading to the establishment of a flexible, multi-level hollow stem discrete element rice model. This model facilitated an examination of the normal and tangential threshing forces from a microscopic perspective, thereby validating the performance of the flexible drum-shaped threshing element. Optimization simulation tests were then performed, with drum speed, feeding amount, and threshing gap serving as test factors, while the crushing rate and loss rate were used as test indexes. The results indicate that, under the optimal structural parameters of the threshing element, the ideal configuration includes a drum speed of 900 rmp, a feeding amount of 3.734 kg/s, and a threshing gap of 23.214 mm, resulting in a normal force of 18.05 N and a tangential force of 12.96 N, with a loss rate of 0.929%. Finally, a field harvest verification test was conducted based on these optimization results. Under identical working parameters, the breakage rate of the newly designed flexible threshing element was reduced by 55.9% compared to the traditional steel nail teeth, while the loss rate decreased by 15.3%, thereby fulfilling the high-quality harvesting requirements for rice seeds.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Rice is one of the world’s major food crops, with China being the largest producer and consumer of rice1.As the population continues to grow while the area of cultivated land decreases, the cultivation of superior rice varieties can help alleviate food pressure in the country2.Currently, to enhance harvesting efficiency and reduce costs, rice seed production primarily depend on combine harvesters for seed harvesting3.During the threshing process, the collision between the seeds and the rigid surfaces of the threshing device can easily cause damage, adversely affecting the subsequent germination rate of the seeds4,5. The primary factors contributing to mechanical damage to seeds include the impact of threshing elements, drum speed, gravure gap, and feeding amount. Among these, the impact of threshing elements on rice grains is the direct cause of seed breakage6,7. Additionally, the breakage rate of seeds during harvesting is influenced by variations in rice varieties, moisture content, and maturity8,9.

Currently, ensuring the integrity of rice seeds presents a technical challenge during rice seed harvesting. Duane L et al. analyzed the effects of grain speed, physical properties, moisture content, collision material, and collision angle on the extent of mechanical collision damage and indicated that altering the structure of threshing elements can effectively reduce grain damage10. Tang et al. investigated the propagation of cracks in rice grains, elucidating the fracture mechanism and establishing the relationship between impact toughness and fracture speed11. Kamst et al. examined the effects of blowing speed and crop humidity on the breakage rate, concluding that humidity is inversely proportional to the breakage rate, while blowing speed is directly proportional to it12. Xu et al. studied the stress experienced during the collision between rice grains and nail teeth, revealing that maximum stress occurs at the center of the collision, with macro cracks expanding outward from this point13. Li et al. quantified the degree of damage to rice by utilizing the free surface energy of new surfaces created by damage, comparing the breakage rates of two types of nail teeth—circular and rectangular cross-sections and found that the breakage rate of the circular cross-section was lower than that of the rectangular cross-section14. Wang et al. explored the relationship between the speed of threshing elements and the rice grain breakage rate, establishing a mathematical model that relates the linear speed of circular cross-section threshing elements to the grain breakage rate15.

To minimize damage to seeds during the threshing process, some scholars have proposed the use of rubber materials, which are gentler than steel, as threshing elements. Xie et al. replaced traditional rigid nail teeth with a flexible toothed threshing drum, significantly reducing the breakage rate of rice grains during threshing16. Li et al. designed a nail tooth made of EPDM rubber, and tests demonstrated that this flexible nail tooth exhibits a lower breakage rate and improved wear resistance17. Ren et al. developed a power consumption model comparing rigid-tooth and flexible-tooth threshing drums, revealing that the power consumption of the flexible-tooth drum is lower under the same feeding amount18. Su et al. created a curved nail tooth using nitrile rubber and polyurethane rubber and indicated that the breakage rates of these two flexible threshing elements were lower than that of the traditional trapezoidal nail tooth19. Qian et al. established a dynamic model of frictional contact between the threshing gear rod and rice based on multi-body system theory and showed that continuous normal force and minimal tangential force are generated during the flexible threshing process, which helps reduce grain damage20. However, despite the advantages of rubber threshing elements in reducing seed damage, there is a concurrent decrease in threshing force, which complicates the removal of rice seeds and leads to drum clogging, as well as an increase in the rate of non-threshing.

In addition, to optimize the structure of the threshing device and enhance its overall performance, numerous scholars have conducted mechanism analyses on the threshing and movement processes of grains within the threshing chamber, as well as the crushing process of grains21,22. However, the threshing separation process involves a complex interaction between the material flow in the threshing chamber, the threshing device, and its interior components, which cannot be intuitively or accurately described using mathematical models or experimental analyses. With the development and improvement of discrete element method, it is widely used in the agricultural field23,24. Through discrete element simulation, it becomes possible to investigate unmeasurable physical quantities during specific processes and to analyze the motion of materials within a confined space, which is a significant advantage. Wang et al. analyzed the internal movement of seeds with different moisture contents at different angles in a high-level grain unloading barrel25. Wang et al. simulated the rice threshing process within a shear flow drum, examining the behavior of grains in the threshing elements by superimposing speed and force resulting from impact, while also studying the influence of various operating parameters on the non-threshing rate and separation rate26. Su et al. established a discrete element model of grains and straw, investigating the movement speed and displacement of particles within both concentric and non-concentric threshing devices27. Li et al. explored the dynamic response characteristics of rice particles to various parameters, establishing an amplified mathematical model that incorporates both structural and operational parameters28. Currently, in the realm of discrete element modeling of rice, Liu et al. introduced a modeling method specifically for rice hollow stems29, Mao et al. proposed a straw particle model featuring flexible hollow cylindrical bonds30, Xu et al. conducted parameter calibration on an upright whole rice plant model31. However, due to the complexity of the rice plant structure, there are relatively few studies focused on comprehensive modeling of the entire plant. Most existing research typically involves modeling individual parts separately, which neglects the integrity of the rice structure and the interactions between particles that arise from their shapes. This will significantly affect simulation results and parameter optimization.

To address the aforementioned issues, this research aims to achieve the following primary objectives: (1) To innovate a flexible drum-shaped threshing element that minimizes the impact damage to seeds while enhancing the rubbing effect, thus improve the threshing rate and resolve the contradictory relationship between the damage rate and the threshing rate. (2) To enhance the reliability of the simulation results, a flexible multi-level hollow stem rice DEM model was developed and calibrated. Based on this, a three-factor, five-level orthogonal rotation combination test was conducted, where drum speed, feeding amount, and threshing gap were the test factors. The normal force, tangential force, and loss rate served as the test indicators to identify the optimal working parameters, followed by field trials for verification.

Materials and methods

Low damage flexible threshing drum

This study focuses on optimizing the design of threshing elements for a longitudinal axial flow threshing device. Figure 1 illustrates the overall structure of the threshing device, which measures 2200 mm in length, 650 mm in width, and features a drum diameter of 600 mm. The initial threshing element employed is a steel nail tooth.

The threshing element serves as the core component of the threshing drum. Within the threshing chamber, the threshing element facilitates the detachment of grains through mechanisms such as impacting, combing, squeezing, and rubbing the rice32,33. The falling of grains mainly depends on the impact of threshing elements, but the grains are easily broken during the impact process. The impact force exerted by the threshing elements on the rice can be analyzed in terms of its normal and tangential components. By appropriately reducing the normal force while increasing the tangential force, it is possible to effectively decrease the seed breakage rate during the threshing process. This study presents the design of a drum-shaped flexible threshing element, which aims to diminish the impact of the normal force, enhance the rubbing effect of the tangential force, and ultimately reduce the rate of seed breakage.

Basic structure and materials of flexible drum threshing element

Nail teeth exhibit excellent threshing and separation capabilities, making them widely utilized in threshing devices. This study builds upon the existing design of nail teeth. When the steel nail teeth are rotating with the drum, the busbar is oriented perpendicular to the rotational speed, resulting in significant normal impacts on the rice. This not only increases the seed crushing rate but also leads to the breakage of stems and leaves, consequently extending the workload for the cleaning device. To address these issues, this study employs EPDM rubber to design a drum-shaped threshing element that is thick in the center and tapered at both ends, effectively mitigating the aforementioned problems. The structural design of the element is illustrated in Fig. 2.

EPDM rubber exhibits reliable performance, excellent wear resistance, and high cost-effectiveness. Compared to steel, it is softer and effectively minimizes seed damage. Additionally, its surface roughness exceeds that of steel, which enhances the rubbing effect during the threshing process. The primary parameters of the drum-shaped threshing element include the height of the threshing element, the diameter of the top, and the diameter of the drum body, with the diameter of the drum body being larger than that of the top. In contrast to cylindrical nail teeth, the design featuring an increased diameter in the middle creates a slope on the drum surface. When in contact with rice, this inclined surface provides a buffering effect, thereby reducing the normal impact force and increasing the tangential rubbing force, which ultimately minimizes grain breakage.

Analysis of contact force between rice and drum-shaped threshing element

The collision and contact process between rice grains and threshing elements can be categorized into two stages: elastic collision and inelastic collision. Initially, the threshing element makes contact with the rice grains, resulting in an elastic collision. During this phase, the contact force increases as elastic deformation occurs. As compression continues, the elastic deformation reaches its maximum value, at which point it approaches the limit of the elastic state. Beyond this threshold, further deformation leads to inelastic collisions, which propagate outward from the contact point, resulting in the formation of stress cracks or fractures. Consequently, the rice grains undergo permanent plastic deformation.

This study primarily examines the elastic collision process that occurs when the drum-shaped threshing element makes contact with rice grains, as illustrated in Fig. 3a. Given the curvature of the drum surface, this collision process is categorized as an inclined plane collision. For the inclined collision problem, Hertz’s theory can be applied in the normal direction to investigate the normal contact force34,35. To streamline the analysis and calculations, the following assumptions are established:

-

(1)

The rice grain is simplified into a uniform isotropic ellipsoid.

-

(2)

A center-to-center collision occurs between the rice grain and the threshing element.

-

(3)

The contact point between the threshing element and the rice grain is treated as an elastic half-space body.

-

(4)

Energy dissipation during the collision is neglected.

-

(5)

The effects of other grains, stems, and leaves on the collision process are ignored.

-

(6)

Assume that the initial velocity of rice during the collision is zero.

Contact mechanics analysis of rice collision process. (a) The impact of the drum on the seeds when it rotates. (b) Collision between the top of the threshing element and the seeds. (c) The collision between the threshing element and the kernel from the tangential perspective.Where O1 and O2 are the centers of the threshing drum and the threshing element bearing rod, respectively; ω is the drum speed, rmp; V is the linear speed of the top of the threshing element teeth, m/s; Vn is the normal linear speed of threshing element, m/s;Vt is the tangential linear speed of threshing element, m/s; θ is the angle between the linear velocity of the top of the threshing element teeth and the horizontal direction, °; α is the angle between the normal linear velocity of the threshing element and the horizontal direction, °; β is the angle between the linear velocity of the top of the threshing element teeth and the normal linear velocity of the threshing element, °; R1 is the radius of the threshing disc, m; R2 is the drum body curve radius, m; R3 is the radius of the threshing element bearing bar, m; r is the top radius, m; H is the height of the threshing element, m; h is the distance from the top of the threshing element to the largest drum of the threshing element, m; δ is the embedding distance between the threshing element and the rice grain, m; m1 and m2 are the mass of threshing element and rice grain, respectively, kg.

As illustrated in Fig. 3b, there exists a specific angle between the velocity of the threshing element and the normal force. According to Hertzian theory, the directions of the velocity and the normal force should align. This relationship is based on geometric principles, as shown in Eqs. (1) and (2).

Let \(\:D=\left|\begin{array}{cc}cos\alpha\:&\:sin\theta\:\\\:sin\alpha\:&\:cos\theta\:\end{array}\right|\), Then there is Eq. (3).

In Fig. 3c, according to Hertz’s theory, when the threshing element collides with the rice grain, the normal force \(\:{F}_{n}\)is a nonlinear function of the deformation, as shown in Eq. (4).

Where n is the exponential coefficient. In the Hertz problem, n is 3/2. K is the Hertz contact stiffness, N/m1.5.

Where R is the equivalent contact radius, m; R1’, R2’, R1” and R2” are the maximum and minimum curvature radii when the threshing element contacts the rice grains, m; E* is the equivalent elastic modulus, Pa; E1 and E2 are the elastic moduli of the threshing element and the rice grains, Pa; v1 and v2 are the Poisson’s ratios of the threshing element and the rice grains.

Let \(\:\frac{1}{M{F}_{\left(e\right)}}=\frac{1}{{m}_{1}}+\frac{1}{{m}_{2}}\), where M is the equivalent mass, kg; F(e) is the equivalent mass correction factor. From Newton’s second law, we can get Eq. (7).

Taking the definite integral of both sides of the equation with respect to δ at (0, δmax).

Rearrange Eq. (9)

When δ = 0, there is no collision between the rice grain and the threshing element, dδ/dt represents Vn, which is the relative speed of the rice grain and the threshing element prior to the collision; When δ = δmax ,the relative speed at the point of collision is zero, resulting in the normal contact force reaching its maximum value, as shown in Eq. (11).

After transformation of Eq. (11)

Equation (14) illustrates that the contact force exerted when rice grains interact with the threshing element is influenced by the equivalent elastic modulus, equivalent mass, rotation speed of the threshing element, and the structural parameters of the threshing element. Notably, the drum speed and the structural parameters of the threshing element significantly affect the contact pressure, while the equivalent elastic modulus and mass also play a crucial role, aligning with the findings of Liang et al. and Li et al.36,37. Consequently, to optimize the threshing effect, selecting EPDM with a lower elastic modulus and reduced mass can effectively diminish the normal contact force during the collisions between rice grains and the threshing elements, thereby minimizing grain damage.

Determination of key parameters of flexible drum threshing element

The drum-shaped threshing element possesses three critical structural parameters: the height of the threshing element, the diameter of the top, and the diameter of the drum body. In this study, the designed drum-shaped threshing element is installed on the threshing drum in the form of a rubber sleeve, with the original nail tooth diameter measuring 13 mm and the height measuring 100 mm. The height of the flexible drum threshing element is constrained by the height of the original drum threshing element and the thickness of the flexible rubber sleeve. If the thickness is too thin, it will reduce the wear resistance and service life of the drum rubber sleeve; conversely, if the thickness is too thick, it will impair the threshing performance. Therefore, the thickness of the rubber sleeve is set to 3 mm, resulting in a threshing element height of 103 mm. To ensure the consistency and stability of the top structure of the threshing element, the top diameter is determined by adding the thickness of the rubber sleeve to the original top diameter, resulting in a measurement of 19 mm. At this point, the only undetermined structural parameter is the diameter of the drum body, which is not constrained by the structure of the original threshing drum. Given that the other two structural parameters are fixed, the diameter of the drum body directly influences the magnitude of the normal contact force.

According to the references14,15, the critical stress that induces cracks in the endosperm of the kernel during the threshing process is 31.68 MPa, while the corresponding critical normal contact force is 42.84 N. In this study, the maximum rotation speed of the threshing device is set at 900 rmp, with the maximum normal force equating to the critical normal contact force. The optimal structural parameters for the drum body diameter are determined at this maximum rotation speed.

According to Eq. (14).

The maximum radius of curvature of the drum tooth is R1′=∞, and the minimum radius of curvature is R1"=r. The maximum and minimum radii of curvature of the grain are related to the three-axis dimensions of the grain. According to the grain size measured in Table 1, R2′=Lg2/2Hg = 12.8 mm, R2"=Bg2/2Hg = 3.2 mm, where Lg is the length of the grain, Bg is the width of the grain, and Hg is the height of the grain. The elastic modulus and Poisson’s ratio of EPDM and grain can be obtained from the Table 4. Since the mass of the threshing element is much larger than the mass of the grain, M ≈ m1 = 8.6 × 10− 2 kg. Mass correction factor F(e) = 0.001. Maximum normal force Fnmax=42.84 N. Maximum rotation speed ω = 30πrad/s. Drum radius R1 = 200 mm. Radius of the rod carrying the threshing element R3 = 17 mm. Threshing element height H = 103 mm. The top radius r = 9.5 mm. h is approximately equal to the height of the threshing element minus half the radius of the rod carrying the threshing element, that is, h ≈ 0.5(H-R3) = 43 mm.

Substituting the above parameters into Eq. (15)

The drum diameter can be obtained through geometric relationship

To facilitate processing, the diameter of the drum body is set at 29 mm. Based on this measurement, three structural parameters of the drum-shaped threshing element have been established: the top diameter is 19 mm, the drum body diameter is 29 mm, and the height of the threshing element is 103 mm.

Rice model based on discrete element method

In order to investigate the threshing force and the movement state of grain in the threshing chamber from a microscopic perspective, a comprehensive model of the entire rice plant was developed. This study focuses on the “Shuyounuo No. 81” rice variety and constructs a model based on the physical and biological characteristics previously studied by the laboratory38. The biological characteristics are detailed in Table 1. To simplify the modeling and simulation process, the rice plant model is reduced to include one rice ear, two leaves, and three sections of hollow stems. The modeling process is illustrated in Fig. 4.

Rice plant discrete element model

(1) Establishment of rice ear modeling simulation model.

As illustrated in Fig. 5. The main cob comprises 40 particles, each with a diameter of 2 mm, while the primary branches consist of 40 particles with a diameter of 1 mm. “Shuyounuo No. 81” is classified as japonica rice, which is characterized by its short and round appearance. Consequently, the rice grains are modeled using five spheres. The angle between the primary branch and the main cob is designated as angle α, while the angle between the grain and the branch is referred to as angle β.

(2) Establishment of stem modeling simulation model.

The rice stem model utilized in this study comprises two leaves and three internodes, as illustrated in Fig. 5. By importing the three-dimensional model of the leaf, a rice leaf constructed from 1279 particles of varying sizes was efficiently generated. The leaves are positioned at the intersection of the stems, with an angle γ formed between the leaves and the stems. The hollow stem internodes consist of rings made up of six particles arranged tangentially, with the center of each ring aligned along the same straight line. The primary stalk is constructed from 188 hollow ring segments, each with an inner diameter of 0.5 mm, an outer diameter of 1.5 mm, and a height of 1 mm. The secondary stalk comprises 150 hollow ring segments, with an inner diameter of 0.75 mm, an outer diameter of 2.25 mm, and a height of 1.5 mm. Finally, the tertiary stalk is formed by the accumulation of 128 hollow ring segments, featuring an inner diameter of 1 mm, an outer diameter of 3 mm, and a height of 2 mm.

Particle contact mechanics model

Since the traditional solid stalk model can not accurately reflect the mechanical properties of rice hollow stalk, a multistage hollow stalk rice model was constructed in this study. As illustrated in Fig. 6, the particles situated between the two sets of rigid rings correspond one-to-one, forming parallel bonds that transmit force and moment at the contact point. As depicted in Fig. 7, when either the normal force or the tangential force reaches its maximum value, the parallel bonding bond breaks38. The parallel bond between the two rings is treated as a hollow Bernoulli beam. According to the mechanics of materials, the normal stiffness and tangential stiffness of the ring section beam per unit area can be expressed as Eqs. (19) and (20).

Where kn is the normal stiffness of the hollow particle, N/m3; kτ is the tangential stiffness of the hollow particle, N/m3; EP is the elastic modulus of the hollow particle, Pa; GP is the shear modulus of the hollow particle, Pa; L is the distance between the centers of two hollow particles, m.

When the particle shape and accumulation are fixed, the macroscopic Poisson’s ratio is related to kn/kτ39. Consequently, the normal-to-shear stiffness ratio of the hollow particles is established to be equal to the actual elastic-to-shear modulus ratio, as demonstrated in Eq. (21).

Where E is the actual elastic modulus of rice, Pa; G is the actual shear modulus of rice, Pa; and µ is the Poisson’s ratio of rice.

The overall normal stiffness of the internodes is determined by the series connection of parallel keys between N rings40. The overall normal stiffness of the internodes can be represented as shown in Eq. (22).

Where kni is the normal stiffness of the whole stem model, N/m; kτi is the tangential stiffness of the whole stem model, N/m; Av is the cross-sectional area of the hollow stem model, m2; N is the number of hollow stem particles.

Illustration of the particle bonding. Where r1 is the physical radius of the particle, mm; r2 is the bonding radius, mm; L is the distance between the two particles, mm; Ft and Fn are the normal force and tangential force of the bonding bond, N; Mt and Mn are the normal and tangential moments of the bonding bond, N•m.

As illustrated in Fig. 8a, a tensile test was conducted on various segments of the rice plant using a texture analyzer, resulting in the acquisition of force and deformation curves. The test curve was subjected to linear fitting, as depicted in Fig. 8c. The slope derived from this linear fitting represents the actual normal stiffness38. Under the assumption that the normal stiffness of each segment of the rice plant is equivalent to that of the particle model, the actual normal stiffness values for each segment are substituted into Eq. (23) to determine the parallel bond unit normal stiffness for each segment of the rice plant modle, as presented in Eq. (25).

In other words,

where knr is the actual normal stiffness of the stem, N/m.

The unit normal stiffness and unit shear stiffness of the other components of the model can be derived using the aforementioned formulas.

The maximum tensile force can be identified from the tensile test curve. As the tensile force continues to increase, when it exceeds the maximum tensile force, the test specimen will experience axial fracture. The critical normal stress can be represented by Eq. (27).

Where σmax is the critical tensile stress, Pa; Fnmax is the maximum tensile force, N; Ar is the actual cross-sectional area of the stem, m2.

As illustrated in Fig. 8b, a shear test was performed on each component of the research subject using a texture analyzer. The resulting test curve is presented in Fig. 8d. The testing process can be categorized into four distinct stages. Initially, the stem is compressed, leading to elastic deformation that transforms the hollow ring cross-section into an elliptical shape. As the shear force escalates, the stem undergoes further deformation and enters the yield stage. With continued increases in shear force, the upper and lower surfaces of the stem walls come into contact, resulting in an increase in shear resistance, thereby entering the strengthening stage. Ultimately, when the shear force surpasses the maximum shear threshold, the test specimen fails, and the critical shear stress can be expressed as Eq. (27).

Where τmax is the critical shear stress, Pa, Fτmax is the maximum shear stress, N.

Based on the aforementioned analysis, the bonding parameters of various components of rice particles can be obtained, as presented in Table 2.

Simulation parameters

To ensure that the rice discrete element model accurately reflects the real physical characteristics of the rice plant, the parameters necessary for simulation were obtained through a review of relevant literature and the execution of contact parameter tests38, as presented in Table 3.

Figure 9a illustrates the measurement test for the static friction coefficient. The material under examination is positioned on the angle adjustment platform, with grains and stems placed on its surface. Initially, the platform is set at an angle of 0 degrees. The angle of the adjustment platform is then gradually increased. When the grains and stems begin to move or show a tendency to move, the process is halted, and the reading from the angle measuring instrument is recorded. This procedure is repeated 10 times to obtain an average value. The static friction coefficient is defined by Eq. (29).

Where µ1 is the static friction coefficient; λ is the angle at which the motion trend is generated, °.

Figure 9b illustrates the measurement test for the kinetic friction coefficient. The material under investigation is positioned on an angle adjustment platform, which is fixed at 45 degrees. Seeds and stems are placed at a height of 40 mm and allowed to roll to the bottom under the influence of gravity. The motion is recorded using a high-speed camera. During this process, the velocities of the grains and stems as they roll downward are calculated based on the camera’s frame rate and the coordinates from grid paper. This procedure is repeated 10 times to obtain an average value. The kinetic friction coefficient is then calculated using the kinetic energy theorem, as demonstrated in Eq. (30).

Where µ2 is the coefficient of kinetic friction; h1 is the height of the slope, m; η is the angle of the slope, °; v is the speed at which the object rolls to the bottom, m/s; g is the acceleration due to gravity, m/s2.

Figure 9c illustrates the measurement test for the restitution coefficient. The seeds and stems are released from a height of 100 mm in free fall. The material under investigation is positioned at the bottom. The maximum height achieved by the grains and stems after contacting the material is recorded using a high-speed camera. This process is repeated 10 times, and the average is calculated. The recovery coefficient among the grains, stems, and various materials is determined using Eq. (31).

Where e is the coefficient of restitution; h2 is the free fall height, m; and h3 is the maximum rebound height, m.

The simulation parameters obtained from experimental measurements and literature review were incorporated into the developed discrete element model of rice, with the median value selected for parameters that exhibited a range. At this stage, the complete flexible rice plant model has been constructed; however, the accuracy of the model requires further verification.

Simulation-based optimization experimental design

Simulation test method

This study focuses on the longitudinal axial flow threshing device of the intelligent harvester for rice seed production, which has been independently developed by the research group. The three-dimensional model of this device was imported into EDEM for subsequent simulation. The threshing elements consist of EPDM drum-shaped teeth, with a spacing of 70 mm and 140 mm, arranged in a spiral staggered configuration. A receiving box, consisting of 7 rows and 5 columns, is positioned beneath the threshing device. The columns are numbered from left to right as 1 to 5, while the rows are numbered from front to back as 1 to 7. Additionally, baffles are installed on both sides below the threshing chamber to prevent the stripped kernels from escaping the simulation calculation area.

A virtual plane measuring 200 mm by 100 mm is established 0.5 m in front of the feeding device, serving as a pellet factory for the generation of rice plants. Each rice plant has a mass of 26.78 g, and the factory operates at a production rate of 600 plants per second. The objective is to generate a total of 187 rice plants. These generated rice plants descend onto a conveyor belt at a velocity of 2 m/s. Once all the rice plants have been deposited onto the conveyor belt, they are transported to the spiral feeding port at the same speed of 2 m/s, as illustrated in Fig. 10. The drum initiates a counterclockwise rotation at 0.01 s, with a rotational speed set to 700 rmp and a threshing gap of 25 mm. The simulation runs for a duration of 2.5 s, with a time step of 1.2 × 10− 6 s, and test data is recorded every 0.05 s.

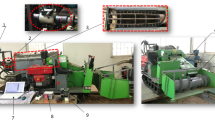

Model validation scheme

To verify the accuracy of the rice model and the effectiveness of the simulation test, a verification test was conducted using a self-developed longitudinal axial flow rice threshing bench, as illustrated in Fig. 11. The conveyor belt has a total length of 2 m and operates at a speed of 2 m/s. A total of 5 kg of rice was evenly distributed on the conveyor belt, with the rice stalk length aligning with the discrete element rice model. The grass-to-grain ratio was maintained at 1.33, while the measured moisture content of the rice grains was 26.83%, and the moisture content of the straw was 69.67%. The threshing drum is driven by a hydraulic motor, with the threshing gap adjusted via a hydraulic cylinder. Thirty-five receiving boxes are positioned beneath the threshing drum to collect the falling materials. The threshing element in the bench test consists of EPDM drum-shaped teeth. The operational parameters of the threshing device align with the simulation design outlined in “Simulation test method”. A comparison is made between the statistics of the distribution of falling materials in both the axial and radial directions for the bench test and the simulation test to verify the results.

Orthogonal rotation combination simulation test design

To investigate the optimal operating parameters of the low-loss flexible threshing drum, we maintained constant rice model and simulation parameters while varying three experimental factors: drum speed (z1), feeding amount (z2), and threshing gap (z3). The normal force (y1), tangential force (y2), and threshing loss rate (y3) experienced by the rice during processing served as the test indicators for a three-factor quadratic regression orthogonal rotation combination test. At threshing element speeds ranging from 16 to 28 m/s, rice grains are less prone to damage15.Considering the structural parameters of the drum outlined in this study, the drum speed was set between 500 and 900 rmp. Additionally, based on the rated feeding capacity and gap adjustment capabilities of the threshing device, the feeding amount was set to range from 3 to 7 kg/s, while the threshing gap was adjusted between 10 and 40 mm. The coding table is presented in Table 4. The normal and tangential forces acting on the rice were obtained through EDEM post-processing, while the loss rate was calculated as the ratio of lost grains to the total number of grains prior to separation. The test plan and results are summarized in Table 5.

Field harvest trial verification

Experimental materials and locations

From June 4 to 7, 2024, a field trial for rice seed production and harvesting was conducted at Changpozi Garden in Xinlong Town, Dongfang City, Hainan Province (18º 57′ N, 108º 40′ E). The experimental rice variety used was “Shuyounuo No. 81”, characterized by a plant height ranging from 900 to 115 cm, a grain moisture content of 21.1–25.3%, a stem moisture content of 65.3–74.2%, and a grass-to-grain ratio of 1.24. The harvesting was performed using the 4LZ-7G2A rice seed propagation harvester, which was independently developed by the research group. A processed flexible drum-shaped threshing element was installed on the threshing drum, as illustrated in Fig. 12. The harvesting operations adhered to the standards outlined in “GB/T8097-2008 Harvesting Machinery Combine Harvester Test Methods” and “NY/T 498–2013 Rice Combine Harvester Quality Evaluation Technical Regulations.”

Test methods

Before the experiment, an oilcloth was secured at the grass discharge outlet to collect entrained lost seeds and unthreshed seeds. The rice seeds harvested from each experimental group were gathered into sacks at the grain outlet. After weighing, a collection bag was employed to gather samples for assessing the breakage rate of each group. To minimize the influence of external factors, a field characterized by flat terrain and uniform plant growth was chosen for the experiment. Each test group was subjected to a stroke length of 50 m, and both testing and sampling were repeated three times for each group. The average values for the seed breakage rate and loss rate were subsequently calculated, with the relevant formulas presented in Eqs. (32) and (33).

Where p1 is the seed breakage rate; p2 is the seed loss rate; M is the total mass of the sample, kg; m1 is the mass of the broken kernels, kg; m2 is the mass of the unremoved kernels, and m3 is the mass of the unseparated kernels, kg.

Results and discussion

Model validation results analysis

In Fig. 13, the threshing distribution pattern observed in the simulation test aligns closely with that of the bench verification test. The maximum relative error between the two sets of tests is 5.2%. This error may be attributed to parameter inaccuracies in the simulation process and inherent randomness in the actual test. However, this error has minimal impact on the overall results of the test. Consequently, the constructed rice discrete element model is deemed accurate.

Simulation results analysis

Analysis of threshing process

As shown in Fig. 14a, the material enters the threshing chamber through the spiral feeding head and progresses toward the end of the drum under the influence of the rotating guide blade. During this movement, the rice is subjected to impacts from the threshing element, friction against the gravure screen, and kneading and squeezing within the material flow, resulting in the separation of grains from the grain handles. The detached grains are subsequently entrained in the spiral movement of the material flow. During this process, the centrifugal force generated by the drum’s rotation, combined with the complex interactions within the material flow, allows the threshed seeds to migrate towards the edge of the material layer. As they pass through one side of the gravure screen, the seeds navigate through the gaps in the gravure and enter the collection box, thereby completing the separation process.

Bulk density analysis

Analyzing the internal movement state of the material in the radial section, it can be observed from Fig. 14b that the stacking density of the material layer gradually decreases from the inner wall of the drum toward the center. This phenomenon occurs due to the action of inertia, which causes the material to splash outward. The obstruction provided by the cover plate and the gravure screen results in the gradual accumulation of material along the wall. Consequently, under the compaction of the accumulated material behind, the density of the material exhibits a gradual increase along the radial direction. Notable protrusions are observed in the six areas labeled A, B, C, D, E, and F, within the same range of rings, the material density in these areas is significantly greater than in others, indicating substantial accumulation. This accumulation is attributed to the agitation caused by the threshing element, where the front end of these areas interacts with the material layer. A speed differential exists between the two, leading to this accumulation. As the circumferential distance increases, the accumulation phenomenon diminishes. The contact area between the front end of the threshing element and the material is considerably larger than that of the rear end, suggesting that the material flow possesses a degree of toughness and stiffness, which aligns with practical observations. Areas G and H, although symmetrical, exhibit different accumulation conditions. This discrepancy arises because the drum rotates counterclockwise, causing the material flow to pass through area G first. The diameter of the cover plate exceeds that of the gravure screen, creating a dead corner at the junction where material tends to accumulate due to changes in wall structure. As the drum continues to rotate, the material flows through area H, where the wall surface is excessively smooth, contrasting sharply with the significant accumulation observed in area G.

Analysis of the distribution pattern of exudates

Su et al.27 studied the mass distribution of extrusives in the threshing process of the longitudinal axial flow threshing device, and found that in the axial direction, the percentage of extrusives was negatively correlated with the distance, while in the radial direction, the extrusives showed an open upward quadratic relationship with the distance. The results of this study show that with the movement of the material flow, the percentage of extrusions gradually decreases in the axial direction, and then increases in the radial direction, which is consistent with Su27. As shown in Fig. 14a and c, under the impact of the roller and the friction between the materials, the grains on the rice are threshed and separated into the collection box. In the axial direction, the proportion of extruded objects in the 1–4 region is larger, and the proportion of extruded objects in the 5–7 region is smaller. This is because of the high density of seeds in the initial material flow, most of the seeds that are easy to be threshed are threshed and separated at the front end, and with the backward movement of the material flow, the remaining mainly stalks, leaves and grains that are difficult to be threshed.

As shown in Figs. 13b and 14c, the percentage of falling material in region 4–5 is greater than that in region 1–2, and the amount of falling material in region 3 is the least. This phenomenon can be attributed to the counter-clockwise rotation of the drum, so that the material flow first produces an inertial impact with the gravure mesh in the 4–5 region. The threshed grain moves down, through the gaps and into the collection bin below. When the material reaches the bottom of the gravure screen, the approximate direction of motion of the grain is tangent to the bottom of the gravure screen, and then the flat throwing motion is done under the action of gravity, and the material receiving box in the 1–2 area is entered. Since the grave plate screen located in the 4–5 region first contacts with the material flow, the quantity and density of grains are larger, and the probability of the receiving box falling into the 4–5 region after threshing and separation is also greater. As the material flow continues to rotate and reaches the 1–2 region, the threshing and separation difficulty of grains increases, so the percentage of falling material in the 1–2 region is less than that in the 4–5 region.

Threshing force analysis

When other simulation parameters remain unchanged, the normal and tangential forces experienced by rice under the action of flexible drum-shaped teeth and steel nail teeth are compared and analyzed, as illustrated in the Fig. 15a and b. From 0 to 0.15 seconds, the rice plants are fed into the threshing chamber via the conveyor belt through the spiral feeding head. During this period, the rice plants does not come into contact with the threshing drum, resulting in an almost negligible threshing force. Between 0.15 and 1.5 s, both the normal and tangential forces on the rice plant model increase sharply. This increase is attributed to the accumulation of materials at the front end of the threshing chamber in the early stage, which raises the material density at that location. Consequently, the number and frequency of impacts from the threshing elements on the materials rise, leading to an increase in the average threshing force. Notably, the average normal threshing force exerted by the flexible drum-shaped teeth is 14.41 N lower than that of the steel nail teeth, while the peak tangential force increases by 4.98 N. This indicates that under identical working parameters, the flexible drum-shaped teeth can reduce the probability of seed damage. Qian et al.45 compared the continuous threshing force of rubber teeth and steel teeth. The results showed that the normal force of rubber teeth was smaller than that of steel teeth, and the tangential force was greater than that of steel teeth, which is consistent with our conclusion. This phenomenon can be attributed to the softer rubber material, which offers greater surface friction and results in less damage to the seeds at the same impact speed, in accordance with Eq. (13). Within 1.5 to 2 s, the normal and tangential forces acting on the rice plant model tend to stabilize and decrease. This stabilization occurs as the material moves in a spiral motion toward the end of the drum, influenced by the drum’s rotation and the guide blades. Consequently, the material is transported backward as a whole, alleviating the pressure of material accumulation at the front end. It is observed that the threshing force of the flexible drum-shaped teeth stabilizes earlier than that of the steel nail teeth. Furthermore, the normal force exerted by the drum-shaped teeth remains lower than that of the nail teeth, while the tangential force is greater. This discrepancy may be attributed to the structural design of the drum body in the drum-shaped threshing element. During the drum’s rotation, the rice experiences a ‘centrifugal’ inertial effect. The curved surface structure of the drum amplifies this effect, causing the diameter of the material layer to expand outward. Consequently, the tangential force in the front section increases, facilitating the guiding and conveying of material flow. As a result, the thickness of the material layer is reduced compared to that of the steel nail teeth, leading to a shorter stabilization time for the material layer’s thickness. The thinner material layer decreases the contact area with the surface of the threshing element, increases the contact area with the top, reduces normal collisions, and enhances the friction between the tooth tops and the material flow. Additionally, the threshing force is influenced by operational parameters such as drum speed, feeding amount, and threshing gap, which require further investigation through experimental studies.

Regression analysis of orthogonal rotation combination simulation test

Normal force

As shown in Table 6, the p-values of the regression model for the normal force test are all less than 0.01, while the p-values of the residual model exceed 0.05. This indicates that the regression equation, with normal force as the test index, demonstrates a good fit.

In the experiment, x2, x3, x12 and x22 had extremely significant effects on the normal force (p < 0.01). The influence of x1 and x1 × 2 on the normal force is significant (0.01 < p < 0.05). The effects of x1 × 3, x2 × 3, and x32 on the normal force are not significant (p < 0.05). After removing the insignificant terms, the fitted coded value regression equation is presented in Eq. (34).

The influence of test factors on the normal force, ranked from largest to smallest impact, includes the threshing gap, feed rate, and drum speed. After eliminating the insignificant terms, the resulting regression equation for the normal force is presented in Eq. (35).

Tangential force

As shown in Table 7, the p-values of the regression model for the tangential force test are all less than 0.01, while the p-values of the residual model exceed 0.05. This indicates that the regression equation, with tangential force as the test index, demonstrates a good fit.

In the experiment, x1, x2, x3 and x22 had extremely significant effects on the tangential force (p < 0.01). The influence of x1 × 2 on the tangential force is significant (0.01 < p < 0.05). The effects of x1 × 3, x2 × 3, x12and x32 on the tangential force are not significant (p < 0.05).After removing the insignificant terms, the fitted coded value regression equation is presented in Eq. (36).

The influence of test factors on the tangential force, ranked from largest to smallest impact, includes the drum speed, feed rate, and threshing gap. After eliminating the insignificant terms, the resulting regression equation for the normal force is presented in Eq. (37).

Loss rate

As shown in Table 8, the p-values of the regression model for loss rate test are all less than 0.01, while the p-values of the residual model exceed 0.05. This indicates that the regression equation, with loss rate as the test index, demonstrates a good fit.

In the experiment, x1, x2, x3, x22 and x32 had extremely significant effects on the loss rate (p < 0.01). The influence of x2 × 3 on the loss rate is significant (0.01 < p < 0.05). The effects of x1 × 2, x1 × 3 and x12 on the loss rate are not significant (p < 0.05).After removing the insignificant terms, the fitted coded value regression equation is presented in Eq. (38).

The influence of test factors on the tangential force, ranked from largest to smallest impact, includes the threshing gap, drum speed, and feed rate. After eliminating the insignificant terms, the resulting regression equation for the normal force is presented in Eq. (39).

Simulation experiment interaction analysis

Analysis of the interactive effect between drum speed and feed rate

As illustrated in Fig. 16a, the normal force exerted by the flexible drum-shaped teeth on the rice initially increases with the rotation speed of the drum before subsequently decreasing, while the tangential force continues to rise. According to Eq. (14), an increase in drum rotation speed correlates with heightened impact strength and frequency of the threshing element acting on the rice. As the rotational speed further escalates, the curved surface structure of the flexible drum-shaped threshing element directs the material layer to extend toward the drum wall, thereby increasing the likelihood of contact between the materials and enhancing the frictional effect between the top and the gravure surface. In Fig. 16b, it is observed that as the feed amount increases, both the tangential and normal forces exhibit a trend of initially rising and then falling. This phenomenon occurs because an increase in material density elevates the probability of contact between the threshing element and the rice. However, when the material density becomes excessively high, the internal movement of the material flow becomes obstructed, resulting in reduced fluidity and a diminished likelihood of contact with the threshing element, consequently leading to a decrease in threshing force.

Li et al.46 studied the influence of different rotational speeds on the unstripped rate and entrainment loss rate, and the results showed that with the increase of rotational speed, the unstripped rate and entrainment loss rate gradually decreased. Yu et al.47 found that the greater the rotation speed of the threshing drum, the greater the impact of threshing elements on the grain, and the more easily the grain is broken. In Fig. 16c, the influence of the threshing element on the normal force increases with drum speed, while the loss rate gradually decreases, aligning with the findings of Li46 and Yu47. This phenomenon occurs because higher rotational speeds enhance the likelihood of rice seeds being threshed from the ear. As the feed amount increases, the loss initially decreases before subsequently increasing. This behavior can be attributed to the increased contact probability between the threshing element and the material, as well as between the materials themselves. However, as the feeding amount continues to rise, the overall stiffness of the material increases, which diminishes the threshing effectiveness of the threshing element.

Analysis of the interactive effect between drum speed and threshing gap

In Fig. 17a and b, a negative correlation is observed between the threshing gap and both the normal and tangential forces exerted by the threshing element on the material. This phenomenon occurs because, as the threshing gap increases, the contact area between the threshing element and the rice diminishes, thereby reducing the likelihood of impact, friction, and collision with the rice. Additionally, as the drum’s rotation speed increases, the striking speed of the threshing element rises, leading to a continuous increase in the normal force applied to the rice. However, with further increases in rotational speed, the normal force exerted by the rubber threshing element begins to decline. This decline is attributed to the streamlining of the drum structure, which reduces the effective normal area of action of the threshing element on the rice while simultaneously increasing the area of tangential force.

Figure 17c illustrates that as the threshing gap increases, the loss rate initially decreases before subsequently increasing. This phenomenon occurs because a larger gap enhances the likelihood of grains passing through the gravure screen. However, as the gap continues to expand, the contact area between the threshing element and the material diminishes, leading to a reduced threshing effect on the rice. Furthermore, there is a negative correlation between drum speed and loss rate; as the rotational speed increases, the threshing force applied to the rice also increases, thereby enhancing the probability of effective threshing.

Analysis of the interaction between feed amount and threshing gap

In Fig. 18a and b, the normal and tangential forces exerted on the rice initially increase and subsequently decrease with the rising feeding amount, and they continue to decline as the threshing gap increases. At a constant drum rotation speed, an increase in the feed amount and a reduction in the drum gap lead to a higher frequency of collisions and friction between the threshing element and the rice. However, when the feeding amount becomes excessively large, the impact and kneading capabilities of the threshing element on the material are diminished.

In Fig. 18c, as the feeding amount and threshing gap increase, the loss rate initially decreases before subsequently increasing. In the early stages, the rise in feeding amount and the reduction in threshing gap enhance the interaction between materials, thereby improving threshing efficiency. However, in the middle and late stages, the backward movement speed of the material decreases, leading to significant accumulation of the material layer and a reduction in threshing probability.

Simulation parameter optimization

To explore the optimal working parameters of the two threshing elements, the established regression model was optimized by minimizing the normal force and loss rate while maximizing the tangential force. The constraints included drum speed, feeding amount, and threshing gap. The objective function and constraints are as follows:

Using the Design-Expert optimization solution module, the optimal working parameters for the flexible drum-shaped threshing element are a drum speed of 900 rmp, a feeding amount of 3.734 kg/s, and a threshing gap of 23.214 mm. The predicted normal force is 18.05 N, the predicted tangential force is 12.96 N, and the predicted loss rate is 0.929%. These optimized working parameters were simulated and verified, as illustrated in Fig. 19. The maximum error observed was 12.5%, demonstrating that the model’s predictions are reliable.

Field validation trials field validation trials

To further verify the reliability of the optimization results concerning the working parameters of the EPDM drum-shaped teeth, verification tests were conducted on EPDM drum-shaped teeth and steel nail teeth using the optimized working parameters. It is important to note that adjusting the working parameters of the threshing device during field harvest tests may not achieve the precision necessary to align with the optimized parameters. Therefore, the drum speed was set to 900 rmp, the feeding amount to 4 kg/s, and the threshing gap to 23 mm. The test results are illustrated in Fig. 20. Under identical operating conditions, the breakage rate of the flexible nail teeth was found to be 55.9% lower than that of the steel nail teeth, while the loss rate decreased by 15.3%. This improvement can be attributed to the flexible drum-shaped inclined surface, which buffers the normal impact of the threshing teeth on the rice, enhances friction, and reduces the seed breakage rate during the threshing process. Additionally, the inclined surface of the drum contributes to a thinner material layer during movement, thereby increasing the free flow rate and the probability of a grain passing through the gravure gap. Additionally, we found that the integrity of the discharged stalks at the end of the drum of the flexible threshing device is significantly higher than that of the traditional threshing device. This observation indirectly indicates that the flexible threshing device reduces the normal impact on the rice.

Conclusion

This article presents the design of a low-damage drum-shaped threshing element, with the objective of reducing both the damage rate and the loss rate during seed harvesting. Additionally, discrete element modeling of the rice plant was conducted to analyze the normal and tangential threshing processes of the threshing element at a microscopic level. The study examines the force and loss rate in conjunction with an orthogonal rotation combined test, aiming to address the conflicting relationship between the damage rate and the threshing rate. The specific research content is outlined as follows:

-

1.

To minimize seed breakage during the harvesting process, a low-damage drum-shaped threshing element was designed. A normal contact force model for the threshing process was established through mechanical analysis. The structural parameters of the threshing element were determined based on the principle of minimum normal force. The top diameter measures 19 mm, the drum body diameter is 29 mm, and the height is 103 mm.

-

2.

This study established a flexible hollow-stem rice model by investigating the structural and mechanical properties of rice. The reliability of the model was validated through bench tests. Additionally, the movement dynamics of rice during the threshing process were examined through simulation, and a comparative analysis of the threshing forces exerted by two threshing elements was conducted.

-

3.

A three-factor, five-level orthogonal rotation combination test was conducted, with drum speed, feeding amount, and threshing gap as the test factors, and normal force, tangential force, and loss rate as the test indicators. The influence of the test factors on normal force, ranked from largest to smallest, is as follows: threshing gap, feed rate, and drum speed. For tangential force, the ranking from largest to smallest is drum speed, feed rate, and threshing gap. Regarding the loss rate, the degree of influence, from largest to smallest, is threshing gap, drum speed, and feed rate.

-

4.

Through multi-objective optimization, the optimal working parameters for EPDM drum teeth were determined to be a drum speed of 900 rmp, a feeding amount of 3.734 kg/s, and a threshing gap of 23.214 mm. The predicted normal force is 18.05 N, the predicted tangential force is 12.96 N, and the predicted loss rate is 0.929%. Based on these optimization results, field experiments were conducted, revealing that under the optimal working parameters, the breakage rate of the flexible tine was 55.9% lower than that of the steel tine, and the loss rate was reduced by 15.3%. These findings demonstrate that the flexible drum-shaped threshing element can effectively minimize seed damage and loss during the threshing process, thereby meeting the requirements for rice seed harvesting.

Data availability

The data presented in this study are available on demand from the second author at (hnupeiyuw@foxmail.com).

References

Yuan, L. Progress in super-hybrid rice breeding[J]. Crop J. 5 (2), 100–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cj.2017.02.001 (2017).

Shang, S. et al. Current situation and development trend of mechanization of field experiments[J]. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agricultural Eng. 26 (1), 5–8. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1002-6819.2010.z1.002 (2010).

Zami, M. et al. Performance evaluation of the BRRI reaper and Chinese reaper compared to manual harvesting of rice (Oryza sativa L). Agriculturists 12 (2), 142–150. https://doi.org/10.3329/agric.v12i2.21743 (2015).

Kalkan, F. et al. Strength and frictional properties of popcorn kernel as affected by moisture content[J]. Int. J. Food Prop. 14 (6), 1197–1207. https://doi.org/10.1080/10942911003637319 (2011).

Agelet, L. E. et al. Feasibility of near infrared spectroscopy for analyzing corn kernel damage and viability of soybean and corn kernels[J]. J. Cereal Sci. 55 (2), 160–165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcs.2011.11.002 (2012).

Sharma, A. D., Kunze, O. R. & Sarker, N. N.Impact damage on rough rice[J]. Trans. ASAE. 35 (6), 1929–1934. https://doi.org/10.13031/2013.28817 (1992).

Asli-Ardeh, E., Askari, A. G., Yousef & Saeid, A. Study of performance parameters of threshing unit in a single plant thresher. Am. J. Agricultural Biol. Sci. 4(2)(2009):92–96. https://doi.org/10.3844/ajabssp.2009.92.96

Kawamura, N. & Horio, H. A basic study on harvesting of standing grain[J]. J. Japanese Soc. Agricultural Mach. 33 (2), 156–162. https://doi.org/10.11357/jsam1937.33.156 (1971).

Morishita, T. & Suzuki, T. The evaluation of harvest loss occurring in the ripening period using a combine harvester in a shattering-resistant line of common buckwheat. Japanese J. Crop Sci. 62–69. https://doi.org/10.1626/jcs.86.62 (2017).

Dauda, A. & Aviara, A. N. Effect of threshing methods on Maize grain damage and viability[J]. Agricultural Mechanization in Asia, Africa and Latin America32 (AMA, 2001). 4.

Tang, H. et al. Discrete element method simulation of rice grains impact fracture characteristics[J]. Biosyst. Eng. 237, 50–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biosystemseng.2023.11.011 (2024).

Kamst, G. F. et al. Effect of deformation rate and moisture content on the mechanical properties of rice grains[J]. Trans. ASAE. 45 (1), 145. https://doi.org/10.13031/2013.7857 (2002).

Li, Y., Wang, X. & Xu, L. Threshing injury to rice grain based on the energy conservation[J]. J. Mech. Eng. 43 (3), 160–164. https://doi.org/10.3321/j.issn:0577-6686.2007.03.027 (2007).

Xu, L. & Li, Y. Finite element analysis on damage of rice kernel impacting on Spike tooth[J]. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agricultural Eng. 27 (10), 27–32. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1002-6819.2011.10.005 (2011).

Wang & XianRen Li YaoMing and Xu LiZhang. Relationship between thresher velocities and rice grain broken rate. 16–19. (2007). https://doi.org/10.3321/j.issn:1002-6819.2007.08.003

Xie, F. et al. Threshing principle of flexible pole-teeth roller for paddy rice[J]. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agricultural Eng. 25 (8), 110–114. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1002-6819.2009.08.020 (2009).

Li, Y. B. et al. Preparation and threshing performance tests of rubber composite nail teeth under maize with high moisture content[J]. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 51, 158–167. https://doi.org/10.6041/j.issn.1000-1298.2020.11.017 (2020).

Ren et al. Analysis and test of power consumption in paddy threshing using flexible and rigid teeth. 12–18. (2013). https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1002-6819.2013.05.002

Su, Y. et al. Optimization and experiment of spike-tooth elements of axial flow corn threshing device. Trans. CSAM. 49 (1), 265–272. https://doi.org/10.6041/j.issn.1000-1298.2018.S0.034 (2018).

Qian, Z., Jin, C. & Zhang, D. Multiple frictional impact dynamics of threshing process between flexible tooth and grain kernel[J]. Comput. Electron. Agric. 141, 276–285. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compag.2017.07.022 (2017).

Tang, Z. et al. Breaking paths of rice stalks during threshing[J]. Biosyst. Eng. 204 (1), 346–357. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biosystemseng.2021.02.008 (2021).

Vlăduț, N. V. et al. Contributions to the mathematical modeling of the threshing and separation process in an axial flow combine[J]. Agriculture 12 (10), 1520. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture12101520 (2022).

Berger, R., Kloss, C., Kohlmeyer, A. & Pirker, S. Hybrid parallelization of the LIGGGHTS open-source DEM code. Powder Technol. 278, 234e247. https://doi.org/10.1016/ (2015).

Chen, Z. et al. Simulation and optimization of the tracked chassis performance of electric shovel based on DEM-MBD. Powder Technol. 390, 428–441. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.powtec.2021.05.085j.powtec.2015.03.019 (2021).

Wang, J. et al. Discrete element method simulation of rice grain motion during discharge with an Auger operated at various inclinations[J]. Biosyst. Eng. 223, 97–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biosystemseng.2022.08.020 (2022).

Wang, Q., Mao, H. & Li, Q. Modelling and simulation of the grain threshing process based on the discrete element method[J]. Comput. Electron. Agric. 178, 105790. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compag.2020.105790 (2020).

Su, Z. et al. Simulation of rice threshing performance with concentric and non-concentric threshing gaps[J]. Biosyst. Eng. 197, 270–284. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biosystemseng.2020.05.020 (2020).

Li, A. et al. Study on dynamic response mechanism of rice grains in friction rice mill and scale-up approach of parameter based on discrete element method[J]. Innovative Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 86, 103346. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ifset.2023.103346 (2023).

Liu, F., Zhang, J. & Chen, J. Modeling of flexible wheat straw by discrete element method and its parameter calibration[J]. Int. J. Agricultural Biol. Eng. 11 (3), 42–46. https://doi.org/10.25165/j.ijabe.20181103.3381 (2018).

Mao, H., Wang, Q. & Li, Q. Modelling and simulation of the straw-grain separation process based on a discrete element model with flexible Hollow cylindrical bonds[J]. Comput. Electron. Agric. 170, 105229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compag.2020.105229 (2020).

Xu, C. et al. Determination of characteristics and establishment of discrete element model for whole rice plant[J]. Agronomy, 13(8), 2098. (2023). https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy13082098

Wang, X. R., Shi, Q. X. & Ni, C. N. Study on the impact numbers of threshing tooth on rice grain for semi feeding unit[J]. J. Agricultural Mechaniz. Res. 4, 17–20. https://doi.org/10.13427/j.cnki.njyi.2011.04.056 (2011).

Olaoye, J., Olanrewaju, K. C. & Oni Olaoye. Computer applications for selecting operating parameters of stationary grain crop thresher. Int. J. Agricultural Biol. Eng. 3, 8–18. https://doi.org/10.3965/j.issn.1934-6344.2010.03.008-018 (2010).

Maw, N., Barber, J. R. & Fawcet, I. N. The role of elastic tangential compliance in oblique impact [J]. Transactions of the ASME. J. Lubr. Technol. 10. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.3251617 (1981).

Lizhang, X., Yaoming, L. & Linfeng, D. .Contacting mechanics analysis during impact process between rice and threshing component[J].Trans. Chin. Soc. Agricultural Eng., DOI:doi:https://doi.org/10.3901/JME.2008.09.177. (2008).

Liang, Z. et al. Optimum design of an array structure for the grain loss sensor to upgrade its resolution for harvesting rice in a combine harvester[J]. Biosyst. Eng. 157, 24–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biosystemseng.2017.02.006 (2017).

Lizhang, X. et al. Theoretical analysis and finite element simulation of a rice kernel obliquely impacted by a threshing tooth[J]. Biosyst. Eng. 114 (2), 146–156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biosystemseng.2012.11.006 (2013).

Yang R, Wang P, Qing Y, et al. Establishment of Whole-Rice-Plant Model and Calibration of Characteristic Parameters Based on Segmented Hollow Stalks[J]. Agriculture 15(3),327. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15030327(2025).

Potyondy, D. O. & Cundall, P. A. A bonded-particle model for rock[J]. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 41 (8), 1329–1364. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmms.2004.09.011 (2004).

Coetzee, C. J. & Lombard, S. G. The destemming of grapes: experiments and discrete element modelling[J]. Biosyst. Eng. 114 (3), 232–248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biosystemseng.2012.12.014 (2013).

Xu, L. et al. Numerical simulation of gas–solid two-phase flow to predict the cleaning performance of rice combine harvesters[J]. Biosyst. Eng. 190, 11–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biosystemseng.2019.11.014 (2020).

Li, H. et al. CFD–DEM simulation of material motion in air-and-screen cleaning device[J]. Comput. Electron. Agric. 88, 111–119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compag.2012.07.006 (2012).

Horabik, J. & Molenda, M. Parameters and contact models for DEM simulations of agricultural granular materials: A review[J]. Biosyst. Eng. 147, 206–225. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biosystemseng.2016.02.017 (2016).

Zirnstein, B., Schulze, D. & Schartel, B. Mechanical and fire properties of multicomponent flame retardant EPDM rubbers using aluminum trihydroxide, ammonium polyphosphate, and polyaniline[J]. Materials, 12(12): 1932. (2019). https://doi.org/10.3390/ma12121932

Qian, Z. et al. Modelling threshing using an entropy regularisation approach with frictional contact dynamics and a flexible threshing mechanism[J]. Biosyst. Eng. 226, 144–154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biosystemseng.2023.01.001 (2023).

Li, Y. et al. Power analysis and experiment on longitudinal axial-threshing unit test-bed[J].Nongye Jixie Xuebao/Transactions Chin. Soc. Agricultural Mach., 42(6):93–97. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1000-1298 (2011).

Yu, Y., Fu, H. & Yu, J. DEM-based simulation of the corn threshing process[J]. Adv. Powder Technol. 26 (5), 1400–1409. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apt.2015.07.015 (2015).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China - Youth Science Foundation Project (52305252), the National Key R&D Program-Sub-project, (2023YFD2000400) and the Key R&D project in Hainan Province (ZDYF2024XDNY181).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, R.Y. and Y.Q.; methodology, P.W.; software, P.W.; validation, P.W., L.C. and W.S.; formal analysis, P.W.; investigation, D.C.; resources, R.Y. and Y.Q.; data curation, P.W. and R.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, P.W.; writing—review and editing, Y.Q., P.W., W.S. and D.C.; visualization, L.C.; supervision, Y.Q.; project administration, Y.Q. and R.Y.; funding acquisition, Y.Q. and W.S.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, R., Wang, P., Qing, Y. et al. Discrete element simulation optimization design and testing of low-damage flexible drum threshing elements suitable for high-quality seed harvesting. Sci Rep 15, 13601 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-94007-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-94007-z