Abstract

To investigate the relationship between nutritional and inflammatory status and all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in the U.S. population with cardiometabolic syndrome (CMS) and to identify the optimal nutrition-inflammation index for assessing long-term prognosis. Health data from the 1999–2010 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) were used. Kaplan-Meier analysis explored associations between nutrition-inflammation indices and mortality in the CMS population. Significant indices were selected for ROC curve analysis, and the most effective index was analyzed using COX regression models. Restricted cubic splines (RCS) analyzed nonlinear associations, and a recursive algorithm determined inflection points. Subgroup and sensitivity analyses assessed the stability of the model. The study included data from 5,969 participants (2,900 males, 3,069 females), with 1,753 all-cause deaths and 607 cardiovascular deaths. Kaplan-Meier analysis indicated that good nutrition and low inflammation were linked to better long-term outcomes. The Advanced Lung Cancer Inflammation Index (ALI) was the most effective assessing index. COX regression showed a negative association between ALI and both mortality types. RCS analysis revealed a U-shaped relationship for all-cause mortality and an L-shaped curve for cardiovascular mortality, with an inflection point at 106.24. Subgroup analysis and sensitivity analysis confirmed the robustness of ALI in assessing the mortality risk in the CMS population. ALI is an ideal indicator for evaluating the relationship between nutritional and inflammatory status and both all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in the CMS population. Maintaining an appropriate ALI level can help reduce the risk of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in CMS patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cardiometabolic Syndrome (CMS) is a cluster of metabolic abnormalities, including central obesity, hypertriglyceridemia, low high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, elevated fasting glucose, and hypertension1. These metabolic abnormalities significantly increase the risk of cardiovascular diseases and all-cause mortality. Globally, the prevalence of CMS is rising continuously, along with the associated all-cause and cardiovascular mortality2,3. According to the International Diabetes Federation (IDF), the global prevalence of CMS is approximately 25%4. In the United States, the prevalence of CMS in adults has increased from 28.23% in 1999 to 37.09% in 2018, with an annual growth rate of 1.385%5. Evidently, CMS is rapidly undermining public health and imposing a substantial economic burden on society6. Therefore, studying the risk factors of CMS and strategies for its prognosis is of paramount importance.

Research indicates that individuals with CMS often exhibit dysregulated nutritional and inflammatory states7,8. This population is frequently in a state of overnutrition and insulin resistance, leading to increased fat synthesis and elevated levels of inflammatory factors such as tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interleukin-6 (IL-6), C-reactive protein (CRP), and plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1)9,10,11. These inflammatory factors directly impair endothelial function, promote atherosclerosis, and induce oxidative stress, exacerbating inflammation and causing cellular and tissue damage. This process facilitates the formation and rupture of atherosclerotic plaques, induces thrombosis, and increases the risk of cardiovascular events12,13, thereby elevating cardiovascular mortality in CMS patients. Furthermore, the accumulation of visceral fat and insulin resistance results in a chronic inflammatory state, leading to protein catabolism, nutritional imbalance, muscle atrophy, reduced physical strength, and weakened immunity. These factors reduce the disease resistance of CMS patients, further increasing their all-cause mortality14,15,16. However, the existence of the obesity paradox gives CMS patients a different level of disease resistance, making the phenomenon more complex. Most individuals with CMS, due to obesity, exhibit a lower mortality risk under specific conditions, even showing a higher survival rate for cardiovascular diseases and other health issues17. Therefore, these individuals may possess greater disease resistance than traditionally understood. However, the specific mechanisms behind the obesity paradox remain unclear, and appropriate indices to assess the disease resistance and mortality risk of CMS patients have not been sufficiently explored.

To date, relying on individual inflammatory or nutritional markers may be insufficient to fully assess the nutritional and inflammatory status of CMS patients, especially given the complexity introduced by the obesity paradox. Therefore, identifying an index that can accurately assess the complex relationship between obesity, inflammation, cardiovascular events, and mortality risk in the CMS population is of great significance for optimizing the management and treatment strategies for CMS patients. This study utilizes data from the NHANES database to evaluate the effectiveness of various inflammatory and nutritional indicators in predicting cardiovascular and all-cause mortality, selecting the optimal index to provide a new perspective for CMS management.

Materials and methods

This study utilized the NHANES database, conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). NHANES is a comprehensive survey designed to collect representative information on the health and nutrition of the civilian, non-institutionalized population of the United States. It includes data on demographics, socioeconomic status, dietary intake, and health-related issues. To ensure the diversity of the sample, NHANES employs a stratified, multistage probability sampling method to select participants from across the country. The study protocol was approved by the NCHS Research Ethics Review Board of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and all participants provided written informed consent. Detailed information is available on the NHANES website (https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/index.html) .

Data and sample sources

This study utilized publicly available data from NHANES 1999–2010 to identify individuals with cardiometabolic syndrome (CMS). Participants were classified as having CMS if they met three or more of the following criteria1: (1) waist circumference ≥ 102 cm in men or ≥ 88 cm in women; (2) triglycerides (TG) ≥ 150 mg/dL; (3) high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) < 40 mg/dL in men or < 50 mg/dL in women; (4) fasting glucose ≥ 110 mg/dL; (5) diagnosis of hypertension (systolic blood pressure ≥ 130 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure ≥ 85 mmHg). The inclusion criteria for this study were adult patients (age > 20) diagnosed with CMS. The exclusion criteria were: (1) patients missing elements required to calculate inflammatory indices; (2) pregnant patients; (3) patients with missing health data; (4) participants missing any necessary covariates. Ultimately, the study included a total of 5,969 individuals. The specific selection process is illustrated in Fig. 1.

The calculation formulas for nutritional and inflammatory indices

To thoroughly investigate the impact of inflammation and nutritional status on CMS people’s health outcomes, we included four inflammation and nutrition related indices for comparison18,19,20,21. These indices are the Advanced Lung Cancer Inflammation Index (ALI), C-reactive Protein to Lymphocyte Ratio (CLR), Neutrophil to Serum Albumin Ratio (NPAR), and Neutrophil to Lymphocyte Ratio (NLR). The formulas are as follows:

-

(1)

\({\text{ALI}} = \frac{{{\text{Weight}}\left( {{\text{kg}}} \right)}}{{{\text{Height}}\left( {\text{m}} \right)^{2} }} \times {\text{Albumin}}\left( {{\text{g}}/{\text{dL}}} \right) \times \frac{{{\text{Lymphocyte}}\,\left( {1000\,{\text{cells/}}\mu {\text{L}}} \right)}}{{{\text{Neutrophil}}\left( {1000\,{\text{cells/}}\mu {\text{L}}} \right)}}\)

-

(2)

\({\text{CLR}} = \frac{{{\text{CRP}}\,\left( {{\text{mg/L}}} \right)}}{{{\text{Lymphocyte}}\left( {1000\,{\text{cells/}}\mu {\text{L}}} \right)}}\)

-

(3)

\({\text{NPAR}} = \frac{{{\text{Neutrophil}}\,\left( {1000\,{\text{cells/}}\mu {\text{L}}} \right)}}{{{\text{Albumin}}\left( {g{\text{/dL}}} \right)}}\)

-

(4)

\({\text{NLR}} = \frac{{{\text{Neutrophil}}\,\left( {1000\,{\text{cells/}}\mu {\text{L}}} \right)}}{{{\text{Lymphocyte}}\left( {1000\,{\text{cells/}}\mu {\text{L}}} \right)}}\)

Subsequently, based on the quartiles of ALI, we divided the CMS participants into four groups. Specifically, the first quartile (ALIQ1) was used as a reference, including Quartile 1 (ALIQ1 ≤ 25th percentile), Quartile 2 (ALIQ2 > 25th percentile to ≤ 50th percentile), Quartile 3 (ALIQ3 > 50th percentile to ≤ 75th percentile), and Quartile 4 (ALIQ4 > 75th percentile).

Assessment of mortality

Mortality assessment was determined using the latest National Death Index(NDI) public mortality data set. Causes of death from specific diseases were identified according to the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10). Cardiovascular disease deaths included rheumatic heart disease, hypertensive heart disease, ischemic heart disease, pulmonary heart disease, cardiomyopathy, endocarditis, as well as cerebral hemorrhage, cerebral infarction, subarachnoid hemorrhage, and other cerebrovascular diseases, with the specific codes being I00-I09, I11, I13, I20-I51, and I60-I69.

Covariates

This study, by referencing previous research, considers multiple variables that may influence the relationship between inflammation, nutritional status, and the risk of mortality22,23,24. These variables covered various demographic characteristics of the study population, including age, sex, race, marital status, education level, and income-to-poverty ratio. Additionally, personal health status, smoking and drinking habits, as well as the presence of kidney disease, cancer, and cardiovascular diseases were included. Smoking history was defined as having smoked more than 100 cigarettes in one’s lifetime25,26, and drinking history was defined as having consumed at least one 12-ounce beer, one 5-ounce glass of wine, or 1.5 ounces of liquor in the past year27. The diagnosis of cancer and cardiovascular disease is based on the following questions: “Has a doctor or other health professional ever diagnosed you with any type of cancer or malignant tumor?“28 and “Has a doctor or other health professional diagnosed you with coronary heart disease, angina, heart failure, myocardial infarction, or stroke?“29.Detailed information can be found on the NHANES website. (https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/index.html)

Statistical analyses

The statistical analysis of this study was conducted strictly according to the design methods recommended by the NHANES database, using appropriate weights for each study. For continuous variables that followed a normal distribution, the data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation; for continuous variables that did not follow a normal distribution, the data were expressed as median (25th percentile, 75th percentile). Baseline differences in continuous variables were assessed using ANOVA, and baseline differences in categorical variables were assessed using the χ² test, with results expressed as percentages.

Kaplan-Meier analysis was used to preliminarily investigate the relationship between the four nutrition-inflammation indices and all-cause as well as cardiovascular disease (CVD) mortality in CMS patients. If the curves intersect substantially and the P-value is > 0.05, it may indicate that the hazard ratio changes over time, violating the proportional hazards assumption. If the assumption holds, subsequent COX regression analysis can be performed. The Time-dependent ROC curve was then used to compare the value and efficiency of multiple indices in assessing mortality. The most efficient nutrition-inflammation index was further analyzed using multivariate COX regression models to explore its impact on all-cause and CVD mortality in CMS patients, with results expressed as hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI). This study utilized three models for analysis: a crude model without adjustment for confounding factors; Model 1, which adjusted for age, sex, race, education level, PIR, and marital status to control for demographic factors; and Model 2, which further adjusted for smoking, drinking, cardiovascular disease, cancer, and chronic kidney disease based on Model 1 to control for the impact of prior disease history.

Additionally, we combined restricted cubic spline (RCS) analysis with the multivariable adjusted COX regression model to evaluate the nonlinear relationship between nutrition-inflammation status and all-cause as well as cardiovascular mortality in CMS patients. When a nonlinear relationship was present, a recursive algorithm was used to determine the inflection point and further examine threshold effects. Lastly, subgroup and sensitivity analysis was performed on factors that might affect model stability to assess the stability and reliability of our findings. All analyses were conducted using R software (version 4.3.1). Statistical significance was defined as a two-sided P < 0.05.

Results

Characteristics of participants

We analyzed data from 5,969 participants collected by NHANES between 1999 and 2010 to investigate the relationship between nutrition, inflammation status, and the risk of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality. This included 2,900 male participants and 3,069 female participants, as well as 1,753 participants who died from all causes and 607 participants who died from cardiovascular causes. Based on the quartiles of the ALI, the population was divided into four groups. Significant differences (P < 0.05) were found among the four groups in terms of race, age, BMI, income-poverty ratio, marital status, smoking, kidney disease, heart disease, and cancer. The Q4 group had lower age, higher BMI, lower C-reactive protein, lower disease risk, better lifestyle habits, and lower mortality risk compared to the other groups, as detailed in Table 1.

Kaplan-Meier analysis

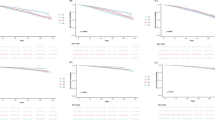

To explore the long-term health implications of nutrition and inflammation status in CMS patients, this study utilized Kaplan-Meier analysis to preliminarily assess the association between four nutrition and inflammation-related indices with all-cause and CVD mortality. The results showed that the ALI index was negatively correlated with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in the CMS population, with higher ALI indicating higher survival rates (PALL<0.0001, PCVD<0.0001). Conversely, inflammation-related indices such as CLR, NPAR, and NLR demonstrated a positive association with mortality, indicating that higher values of these indices were associated with higher mortality risk. Specifically, CLR (PALL<0.0001, PCVD=0.002); NPAR (PALL=0.007, PCVD=0.373); NLR (PALL<0.0001, PCVD<0.0001), suggesting that nutrition is crucial for promoting survival in the CMS population, while chronic inflammation increases the mortality risk. Detailed results are shown in Fig. 2.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves of Nutrition-Inflammation Indices impact on long-term ALL-cause and CVD-cause mortality in CMS patients: (A) Association between ALI and ALL-cause mortality in CMS patients. (B) Association between ALI and CVD-cause mortality in CMS patients. (C) Association between CLR and ALL-cause mortality in CMS patients. (D) Association between CLR and CVD-cause mortality in CMS patients. (E) Association between NPAR and ALL-cause mortality in CMS patients. (F) Association between NPAR and CVD-cause mortality in CMS patients. (G) Association between NLR and ALL-cause mortality in CMS patients. (H) Association between NLR and CVD-cause mortality in CMS patients.

Evaluation diagnostic performance of indices

To determine which nutrition-inflammation index is the most sensitive and effective evaluation metrics of long-term prognosis in the CMS population, we conducted a time-dependent ROC analysis. The results showed that the AUC value of ALI was higher than those of the composite indices NLR, NPAR, CLR, as well as the individual indices of neutrophils, lymphocytes, albumin, and C-reactive protein, for both all-cause and cardiovascular mortality. This demonstrates that ALI has a superior ability to evaluate long-term health outcomes compared to other nutrition-inflammation indices. Detailed results are shown in Fig. 3.

Relationship between ALI and mortality

After identifying ALI as the best nutrition-inflammation index for assessing long-term prognosis in CMS, we used COX multivariate regression models to calculate the relationship between ALI and cardiovascular, all-cause mortality in the CMS population. The results showed that ALI was significantly associated with both all-cause and cardiovascular mortality after adjusting for other potential confounding variables. Specifically, for each unit increase in ALI, all-cause mortality decreased by 0.4%, and the risk of cardiovascular death decreased by 0.8% (see Table 2). This trend was also significant across the ALI quartiles; compared to the Q1 quartile, the Q4 quartile had a 43.6% reduction in all-cause mortality and a 54.6% reduction in cardiovascular mortality. Additionally, there was a clear downward trend in cardiovascular and all-cause mortality risk from Q1 to Q4 quartiles (P for trend < 0.05), as detailed in Table 3. The COX multivariate regression analysis results for other inflammation indices are shown in Table S1.

Non-linear relationships between ALI with mortality in CMS patients

To further determine the potential non-linear association between ALI and cardiovascular and all-cause mortality in CMS patients, we employed Restricted Cubic Spline (RCS) analysis. This allowed us to calculate the inflection points and analyze threshold effects. Our results indicated a U-shaped association between ALI and all-cause mortality in the CMS population, and an L-shaped association with cardiovascular mortality, as shown in Fig. 4.

Using a recursive algorithm, we identified the inflection point for ALI and all-cause mortality, and further examined the threshold effect. For CMS patients, the inflection point was 106.24. To the left of the inflection point, each unit increase in ALI decreased all-cause mortality by 1.2%, while to the right of the inflection point, each unit increase in ALI increased all-cause mortality by 0.2%. Our calculations revealed a negative association between ALI and cardiovascular mortality, with higher ALI associated with lower mortality rates. To the left of the inflection point, each unit increase in ALI decreased cardiovascular mortality by 1.5%, whereas to the right of the inflection point, the relationship between ALI and cardiovascular mortality became insignificant (P > 0.05), as detailed in Table 4. The RCS curves for other indices are shown in Fig. S1.

Subgroup analyses

To ensure the reliability of ALI in assessing long-term prognosis in the CMS population, we conducted a subgroup analysis by using the CMS population to the right of the inflection point as the baseline and comparing the mortality risk in different CMS populations to the left of the inflection point. The results showed that gender, smoking, alcohol consumption, cancer, kidney disease, and heart disease did not affect the model’s evaluative power for long-term prognosis in the CMS population. However, age might influence ALI’s assessment of all-cause mortality in CMS (P for interaction < 0.05). Specifically, ALI was more accurate in assessing long-term survival for CMS patients aged over 60. In this group, if ALI < 106.24, the risk of all-cause mortality was 29.5% higher, and cardiovascular risk was 39.4% higher compared to those with ALI > 106.24. Moreover, the results were potentially more reliable when using ALI to evaluate all-cause mortality for CMS patients with ALI < 106.24 who smoked, consumed alcohol, had (or did not have) cancer, had (or did not have) heart disease, or had kidney disease (P < 0.05). These patients had an increased all-cause mortality risk of 28.2%, 31.6%, 74% (35.4%), 68.5% (34.4%), and 66.6%, respectively, compared to those with ALI ≥ 106.24. For cardiovascular mortality assessment, ALI was more accurate in male patients with ALI < 106.24, as well as in those who smoked, consumed alcohol, did not have cancer, had cardiovascular disease, or had kidney disease (P < 0.05). These groups had higher cardiovascular mortality risks of 69.5%, 64.1% (60.7%), 45.5%, 30.9%, 71.5%, and 59.1%, respectively, compared to those with ALI > 106.24. Overall, the stability of ALI in assessing all-cause and cardiovascular mortality was better in most populations, with the CMS population to the left of the inflection point showing higher risks of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality compared to those to the right of the inflection point (see Figs. 5 and 6).

Sensitivity analyses

To further assess the robustness of the association between ALI and all-cause and cardiovascular mortality risk in the CMS population, we conducted a sensitivity analysis. After excluding individuals who died within one year and those under 40 years old, we performed a sensitivity analysis on 4,845 participants. The results showed that the statistical association between ALI and all-cause and cardiovascular mortality risk remained highly robust. This suggests that ALI is a reliable metric for assessing all-cause and cardiovascular mortality risk in the CMS population (Tables 5 and 6).

Discussion

This study included data from 5,969 participants collected by NHANES from 1999 to 2010 to investigate the relationship between nutritional and inflammatory status and mortality in the population. Among these participants were 2,900 men and 3,069 women, with 1,753 cases of all-cause mortality and 607 cases of cardiovascular mortality. Using Kaplan-Meier analysis to preliminarily explore the relationship between nutritional inflammation indices and mortality, we found that ALI, CLR, NPAR, and NLR were associated with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in the CMS population. Higher ALI was associated with lower mortality, while higher levels of CLR, NPAR, and NLR were associated with higher mortality. This indicates that nutrition is crucial for promoting survival in the CMS population, whereas chronic inflammation increases mortality risk. To further explore which nutritional inflammation index is the best Evaluation metrics of long-term prognosis in CMS, we conducted an ROC diagnostic test. The results revealed that ALI is the best index for assessing long-term prognosis in the CMS population. COX multivariate analysis, after adjusting for other covariates, confirmed the negative association between ALI and both all-cause and cardiovascular mortality. RCS analysis and threshold effect analysis revealed a U-shaped curve relationship between ALI and all-cause mortality, suggesting that before the inflection point, an increase in ALI reduces mortality, while beyond the inflection point, an increase in ALI raises mortality risk. The relationship between ALI and cardiovascular mortality showed an L-shaped curve, where higher ALI was associated with lower cardiovascular mortality risk. Therefore, the study’s results highlight ALI’s evaluative role in the long-term prognosis of the CMS population, urging clinicians to maintain ALI within an appropriate range is crucial for improving the prognosis of CMS patients.

Originally, ALI was an index for assessing the long-term prognosis of patients with advanced lung cancer30. However, due to its comprehensive efficacy in assessing inflammation and nutritional status, it has been used by clinicians to evaluate the risk of diseases such as hypertension31, coronary heart disease32, and diabetes33, demonstrating good evaluative value. Subsequently, ALI has been widely used to evaluate the long-term prognosis of patients with chronic diseases. For instance, Ren Z used ALI to evaluate the long-term survival rate of peritoneal dialysis patients34, Ma Z used ALI to evaluate the all-cause and cardiovascular mortality risk in patients with rheumatoid arthritis35, and Chen X used ALI to evaluate the long-term mortality risk in stroke patients36. Thus, we hypothesized that using ALI to assess the long-term prognosis of CMS patients is feasible. The study results were as expected, showing a close association between ALI and mortality in the CMS population. This may be due to ALI comprising BMI and albumin, which reflect nutritional status, and NLR, which reflects inflammation, fitting well with the chronic inflammation and nutritional imbalance state of CMS patients37,38.

Interestingly, we discovered a U-shaped relationship between ALI and all-cause mortality in CMS. This suggests that on the left side of the inflection point (ALI = 106), an increase in ALI may enhance resistance to disease mortality and reduce all-cause mortality risk in CMS patients.Considering the common diseases in CMS, an increase in ALI on the left side of the inflection point may provide stronger protection against cardiovascular death39, cancer death40, respiratory disease death41, and death from microbial infections42. This might be related to the improved immunity and disease resistance associated with higher ALI. However, it is important to note that a lower risk of disease-related death does not mean CMS patients with higher ALI are less likely to develop these diseases. This point is illustrated by the fact that on the right side of the inflection point, higher ALI increases the risk of all-cause mortality, possibly due to nutritional excess, leading to more disease risk factors and the occurrence of acute and chronic diseases, causing CMS patient deaths. Although individuals with high ALI have higher BMI and albumin levels, which provide stronger resistance to chronic disease-related death, they are also more prone to acute and chronic diseases, resulting in many disease-related death risks that cannot be effectively avoided43,44. For example, nutritional excess can lead to cancer, or obesity can increase the risk of pulmonary infections45,46. Additionally, low NLR may be associated with certain hematological diseases, such as aplastic anemia and lymphoma47,48, further increasing mortality risk. Regarding the relationship between ALI and cardiovascular mortality risk, we observed an L-shaped negative association curve, indicating that as ALI increases, cardiovascular mortality risk decreases. This could be because albumin has a strong effect on preventing oxidative stress and regulating endothelial function, protecting blood vessels, and preventing acute myocardial infarction and cardiogenic shock in CMS patients49,50. Moreover, studies have reported that higher NLR is associated with increased rates of acute myocardial infarction and stroke, and lower NLR correlates with higher ALI, thus reducing cardiovascular mortality risk in patients with higher ALI51. In summary, the relationship between ALI and mortality in CMS patients reflects the widespread presence of the “obesity paradox” in this population. Although obesity is generally associated with a higher risk of mortality, in CMS patients, a higher BMI (which correlates with a higher ALI) may be linked to a lower risk of death. This may be attributed to the increased body fat providing greater energy reserves and enhanced stress resistance, particularly after severe illness or acute events, thereby helping to reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality. Therefore, ALI measurement not only assesses inflammation status but also reflects nutritional status, offering a more comprehensive prediction of long-term outcomes in CMS patients.

Furthermore, subgroup analysis showed different effect values of ALI in assessing mortality risk among various CMS populations. In the analysis of ALI assessing all-cause mortality and cardiovascular mortality, we found that CMS patients younger than 60 years old were not suitable candidates. This could be due to the greater impact of nutritional and inflammatory status on the elderly52, as younger populations generally have stronger disease resistance and their metabolic and protective hormone levels are healthier. When their nutritional and inflammatory levels become disturbed, their bodies can quickly adjust and restore balance without resulting in severe outcomes like death53,54. Moreover, the evaluative effect of ALI on CMS people all-cause mortality risk varies by gender, possibly due to different hormone protection mechanisms. Testosterone promotes protein synthesis and has anti-inflammatory effects, while estrogen protects vascular endothelium and the nervous system. These differences in disease types between genders lead to inconsistencies in all-cause mortality risk among the CMS population55,56,57. Similarly, the predictive model for cardiovascular mortality was less effective in CMS women, possibly due to healthier lifestyles and estrogen’s protective effects, which reduce their susceptibility to cardiovascular diseases58,59. Subgroup analysis also indicated that non-smoking and non-drinking CMS populations had less effective models for assessing long-term prognosis using ALI. This could be because their inherent lower risk of lung cancer, liver cancer, and cardiovascular diseases results in less noticeable mortality risk60,61,62. Additionally, we found that using ALI to evaluate cardiovascular and all-cause mortality risks was more effective in CMS patients with kidney disease, cancer, or cardiovascular disease than in those without these conditions. This aligns with clinical observations, as patients with these conditions have more vulnerable nutritional and immune statuses, making ALI a more suitable index of long-term prognosis. In contrast, those without these diseases have relatively stable nutritional and immune statuses, and fluctuations in nutrition and inflammation do not significantly impact their long-term prognosis63,64,65. Therefore, using ALI to evaluate long-term prognosis in CMS patients with existing diseases is relatively stable and reliable.

Overall, our study has several advantages and significant clinical implications. To our knowledge, our study is the first to investigate and establish the relationship between nutritional and inflammatory status and all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in the CMS population, making it innovative. Additionally, we established ALI as the best index for assessing nutritional and inflammatory status in the CMS population, demonstrating that a high-nutrition, low-inflammation status can improve long-term survival rates for CMS patients. Furthermore, we noted the U-shaped curve relationship between ALI and all-cause mortality, suggesting that clinicians and patients should consciously control ALI levels, maintaining them around the appropriate range to ensure better long-term prognosis for the CMS population. Nevertheless, our study is not without limitations. Firstly, a multitude of potential factors could impact ALI and mortality rates. Despite incorporating covariates like chronic kidney disease, cancer, and cardiovascular disease that can affect nutritional and inflammatory status, it is challenging to account for all possible confounding factors. Hence, our findings should be interpreted cautiously and verified by future research. Secondly, although this is a cohort study that can explore the association between ALI and both all-cause and cardiovascular mortality risks in the CMS population to some extent, accurate causality cannot be firmly established due to the presence of objective factors. For example, the study may be subject to bias. Aside from objective physical and blood test indicators, self-reported data in the covariates could be influenced by subjective responses or interviewer-induced biases, leading to inaccuracies. Lastly, the applicability of our findings to other populations may be limited by variations in genetic backgrounds, lifestyles, healthcare quality, and socio-economic factors across different regions. Therefore, when extending these findings to a global context, it is essential to consider regional specificities. Future studies should aim to include a more diverse sample, encompassing various countries and cultures, to improve the generalizability and relevance of the results.

Conclusion

ALI is an ideal indicator for evaluating the relationship between nutritional and inflammatory status and both all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in the CMS population. Maintaining an appropriate ALI level can help reduce the risk of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in CMS patients.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Abbreviations

- CMS:

-

Cardiometabolic syndrome

- NCHS:

-

National Center for Health Statistics

- NHANES:

-

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

- ALI:

-

Advanced lung cancer inflammation index

- NPAR:

-

Neutrophil to Serum Albumin Ratio

- CLR:

-

C-reactive protein to Lymphocyte Ratio

- NLR:

-

Neutrophil to Lymphocyte Ratio

- BMI:

-

Body Mass Index

- PIR:

-

Poverty Income Ratio

- CVD:

-

Cardiovascular Disease

- CKD:

-

Chronic Kidney Disease

- HR:

-

Hazard ratios

- CI:

-

Confidence intervals

- RCS:

-

Restricted cubic spline

References

Grundy, S. M. et al., et al. Definition of metabolic syndrome: Report of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute/American Heart Association conference on scientific issues related to definition. Circulation. 109(3):433-8. (2004).

Arnlöv, J., Ingelsson, E., Sundström, J. & Lind, L. Impact of body mass index and the metabolic syndrome on the risk of cardiovascular disease and death in middle-aged men. Circulation 121 (2), 230–236 (2010).

Gami, A. S. et al. Metabolic syndrome and risk of incident cardiovascular events and death: a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 49 (4), 403–414 (2007).

O’Neill, S. & O’Driscoll, L. Metabolic syndrome: a closer look at the growing epidemic and its associated pathologies. Obes. Rev. 16 (1), 1–12 (2015).

Yang, C. et al. Trends and influence factors in the prevalence, intervention, and control of metabolic syndrome among US adults, 1999–2018. BMC Geriatr. 22 (1), 979 (2022).

Curtis, L. H. et al. Costs of the metabolic syndrome in elderly individuals: findings from the cardiovascular health study. Diabetes Care 30 (10), 2553–2558 (2007).

Monteiro, R. & Azevedo, I. Chronic inflammation in obesity and the metabolic syndrome. Mediators Inflamm. 2010, 289645 (2010).

Cooke, A. A., Connaughton, R. M., Lyons, C. L., McMorrow, A. M. & Roche, H. M. Fatty acids and chronic low grade inflammation associated with obesity and the metabolic syndrome. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 785, 207–214 (2016).

You, T. et al. The metabolic syndrome is associated with Circulating adipokines in older adults across a wide range of adiposity. J. Gerontol. Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 63 (4), 414–419 (2008).

Bertin, E. et al. Plasma levels of tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-alpha) are essentially dependent on visceral fat amount in type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes Metab. 26 (3), 178–182 (2000).

Alessi, M. C. et al. Production of plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 by human adipose tissue: possible link between visceral fat accumulation and vascular disease. Diabetes 46 (5), 860–867 (1997).

Liberale, L. et al. Inflammation, aging, and cardiovascular disease: JACC review topic of the week. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 79 (8), 837–847 (2022).

Ruscica, M., Corsini, A., Ferri, N., Banach, M. & Sirtori, C. R. Clinical approach to the inflammatory etiology of cardiovascular diseases. Pharmacol. Res. 159, 104916 (2020).

Nishikawa, H., Asai, A., Fukunishi, S., Nishiguchi, S. & Higuchi, K. Metabolic syndrome and sarcopenia. Nutrients 13 (10), 3519 (2021).

Jin, S. M. et al. Change in serum albumin concentration is inversely and independently associated with risk of incident metabolic syndrome. Metabolism 65 (11), 1629–1635 (2016).

Prado, C. M., Batsis, J. A., Donini, L. M., Gonzalez, M. C. & Siervo, M. Sarcopenic obesity in older adults: a clinical overview. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 20 (5), 261–277 (2024).

Simati, S., Kokkinos, A., Dalamaga, M. & Argyrakopoulou, G. Obesity paradox: fact or fiction?? Curr. Obes. Rep. 12 (2), 75–85 (2023).

Song, M. et al. The advanced lung cancer inflammation index is the optimal inflammatory biomarker of overall survival in patients with lung cancer. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 13 (5), 2504–2514 (2022).

Chen, X., Lin, Z., Chen, Y. & Lin, C. C-reactive protein/lymphocyte ratio as a prognostic biomarker in acute pancreatitis: a cross-sectional study assessing disease severity. Int. J. Surg. 110 (6), 3223–3229 (2024).

Gao, Y. et al. Association of neutrophil and albumin with mortality risk in patients receiving peritoneal Dialysis. J. Ren. Nutr. 34 (3), 252–259 (2024).

Qi, L. et al. Morphological changes of Peri-Coronary adipose tissue together with elevated NLR in acute myocardial infarction patients in-Hospital. J. Inflamm. Res. 17, 4065–4076 (2024).

Yao, J., Chen, X., Meng, F., Cao, H. & Shu, X. Combined influence of nutritional and inflammatory status and depressive symptoms on mortality among US cancer survivors: findings from the NHANES. Brain Behav. Immun. 115, 109–117 (2024).

Gao, X. et al. Combined influence of nutritional and inflammatory status and breast cancer: findings from the NHANES. BMC Public. Health 24 (1), 2245 (2024).

Liu, B. et al. Positive association between advanced lung cancer inflammation index and gallstones, with greater impact on women: a cross-sectional study of the NHANES database. Front. Nutr. 11, 1506477 (2024).

Lv, X. et al. Associations between nutrient intake and osteoarthritis based on NHANES 1999 to 2018 cross sectional study. Sci. Rep. 15 (1), 4445 (2025).

Guo, T., Zhou, Y., Yang, G., Sheng, L. & Chai, X. Association between cardiometabolic index and hypertension among US adults from NHANES 1999–2020. Sci. Rep. 15 (1), 4007 (2025).

Xu, B. et al. Is systemic inflammation a missing link between cardiometabolic index with mortality? Evidence from a large population-based study. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 23 (1), 212 (2024).

Chen, R. et al. Interaction between sleep duration and physical activity on mortality among cancer survivors: findings from National health and nutrition examination surveys 2007–2018. Front. Public. Health 13, 1532320 (2025).

Hou, X. Z. et al. Association of sleep characteristics with cardiovascular disease risk in adults over 40 years of age: a cross-sectional survey. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 11, 1308592 (2024).

Lu, P. et al. A low advanced lung cancer inflammation index predicts a poor prognosis in patients with metastatic Non-Small cell lung cancer. Front. Mol. Biosci. 8, 784667 (2022).

Zhang, Y. et al. The advanced lung cancer inflammation index predicts long-term outcomes in patients with hypertension: National health and nutrition examination study, 1999–2014. Front. Nutr. 9, 989914 (2022).

Yuan, X., Huang, B., Wang, R., Tie, H. & Luo, S. The prognostic value of advanced lung cancer inflammation index (ALI) in elderly patients with heart failure. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 9, 934551 (2022).

Chen, Y., Guan, M., Wang, R. & Wang, X. Relationship between advanced lung cancer inflammation index and long-term all-cause, cardiovascular, and cancer mortality among type 2 diabetes mellitus patients: NHANES, 1999–2018. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne) 14, 1298345 (2023).

Ren, Z., Wu, J., Wu, S., Zhang, M. & Shen, S. The advanced lung cancer inflammation index is associated with mortality in peritoneal Dialysis patients. BMC Nephrol. 25 (1), 208 (2024).

Ma, Z., Wu, S., Guo, Y., Ouyang, S. & Wang, N. Association of advanced lung cancer inflammation index with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in US patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Front. Nutr. 11, 1397326 (2024).

Chen, X., Hong, C., Guo, Z., Huang, H. & Ye, L. Association between advanced lung cancer inflammation index and all-cause and cardiovascular mortality among stroke patients: NHANES, 1999–2018. Front. Public. Health 12, 1370322 (2024).

Watanabe, D. et al. Frailty modifies the association of body mass index with mortality among older adults: Kyoto-Kameoka study. Clin. Nutr. 43 (2), 494–502 (2024).

Perrotta, F. et al. Adiponectin is associated with neutrophils to lymphocyte ratio in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. COPD 18 (1), 70–75 (2021).

Amouzegar, A., Mehran, L., Hasheminia, M., Kheirkhah Rahimabad, P. & Azizi, F. The predictive value of metabolic syndrome for cardiovascular and all-cause mortality: Tehran lipid and glucose study. Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. ;33(1). (2017).

Jaggers, J. R. et al. Metabolic syndrome and risk of cancer mortality in men. Eur. J. Cancer. 45 (10), 1831–1838 (2009).

Denson, J. L. et al. Society of critical care medicine discovery viral infection and respiratory illness universal study (VIRUS): COVID-19 registry investigator group. Metabolic syndrome and acute respiratory distress syndrome in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. JAMA Netw. Open. 4 (12), e2140568 (2021).

Zhou, Z., Wang, H., Tan, S., Zhang, H. & Zhu, Y. The alterations of innate immunity and enhanced severity of infections in diabetes mellitus. Immunology 171 (3), 313–323 (2024).

Park, J. et al. Association between high preoperative body mass index and mortality after cancer surgery. PLoS One. 17 (7), e0270460 (2022).

Ohlsson, C., Bygdell, M., Sondén, A., Rosengren, A. & Kindblom, J. M. Association between excessive BMI increase during puberty and risk of cardiovascular mortality in adult men: a population-based cohort study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 4 (12), 1017–1024 (2016).

Sceneay, J. & McAllister, S. S. The skinny on obesity and cancer. Nat. Cell. Biol. 19 (8), 887–888 (2017).

Frasca, D. & McElhaney, J. Influence of obesity on Pneumococcus infection risk in the elderly. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne) 10, 71 (2019).

Lundgren, S. et al. Somatic mutations in lymphocytes in patients with immune-mediated aplastic anemia. Leukemia 35 (5), 1365–1379 (2021).

Barcellini, W., Fattizzo, B. & Cortelezzi, A. Autoimmune hemolytic anemia, autoimmune neutropenia and aplastic anemia in the elderly. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 58, 77–83 (2018).

Hariri, G. et al. Albumin infusion improves endothelial function in septic shock patients: a pilot study. Intensive Care Med. 44 (5), 669–671 (2018).

Xia, M. et al. Impact of serum albumin levels on long-term all-cause, cardiovascular, and cardiac mortality in patients with first-onset acute myocardial infarction. Clin. Chim. Acta. 477, 89–93 (2018).

Diniz, L. R., de Lima, S. G., de Amorim Garcia, J. M. & de Oliveira Diniz, K. L. Neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio as a prognostic predictor in older people with acute coronary syndrome. Angiology 70 (3), 264–271 (2019).

Liu, Z. et al. Dietary patterns, nutritional status, and mortality risks among the elderly. Front. Nutr. 9, 963060 (2022).

Clegg, D. et al. Sex hormones and cardiometabolic health: role of Estrogen and Estrogen receptors. Endocrinology 158 (5), 1095–1105 (2017).

Yeap, B. B. et al. Associations of testosterone and related hormones with All-Cause and cardiovascular mortality and incident cardiovascular disease in men: individual participant data Meta-analyses. Ann. Intern. Med. 177 (6), 768–781 (2024).

Gerdts, E. & Regitz-Zagrosek, V. Sex differences in cardiometabolic disorders. Nat. Med. 25 (11), 1657–1666 (2019).

Xing, E., Billi, A. C. & Gudjonsson, J. E. Sex bias and autoimmune diseases. J. Invest. Dermatol. 142 (3 Pt B), 857–866 (2022).

Modra, L. J., Higgins, A. M., Pilcher, D. V., Bailey, M. J. & Bellomo, R. Sex differences in mortality of ICU patients according to Diagnosis-related sex balance. Am. J. Respir Crit. Care Med. 206 (11), 1353–1360 (2022).

Fa-Binefa, M. et al. Early smoking-onset age and risk of cardiovascular disease and mortality. Prev. Med. 124, 17–22 (2019).

Moissl, A. P. et al. Alcohol consumption and mortality: the Ludwigshafen risk and cardiovascular health (LURIC) study. Atherosclerosis 335, 119–125 (2021).

Connor, J. Alcohol consumption as a cause of cancer. Addiction 112 (2), 222–228 (2017).

Gritz, E. R., Talluri, R., Fokom Domgue, J., Tami-Maury, I. & Shete, S. Smoking behaviors in survivors of Smoking-Related and Non-Smoking-Related cancers. JAMA Netw. Open. 3 (7), e209072 (2020).

Alexandrov, L. B. et al. Mutational signatures associated with tobacco smoking in human cancer. Science 354 (6312), 618–622 (2016).

Stenvinkel, P. et al. Chronic inflammation in chronic kidney disease progression: role of Nrf2. Kidney Int. Rep. 6 (7), 1775–1787 (2021).

Zitvogel, L., Pietrocola, F. & Kroemer, G. Nutrition, inflammation and cancer. Nat. Immunol. 18 (8), 843–850 (2017).

Ou, S. M. et al. Association of estimated glomerular filtration rate with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality: the role of malnutrition-inflammation-cachexia syndrome. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 7 (2), 144–151 (2016).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge NHANES databases for providing their platforms and contributing meaningful datasets.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82474494), National Key Research and Development Program of China (No. 2022YFC3500102), the Beijing Municipal Science and Technology Development Funding Program of Traditional Chinese Medicine (No. JJ-2020-69), and High Level Chinese Medical Hospital Promotion Project (No. HLCMHPP2023065). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Writing the first draft of the manuscript, statistical analyses, data organization, writing review, and editing : XC Huang and LS Hu.Research, statistical analyses, and editing : XL Xie, SY Tao, TT Xue. Design research, supervision, editing, review, revision of the manuscript, and funding: J Li and WJ Zhang.All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Our analyses were performed on the basis of publicly available data, with previous subjects signing an informed consent form.Therefore, this study has no ethical implications.All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Huang, X., Hu, L., Li, J. et al. The association of nutritional and inflammatory status with cardiovascular and all-cause mortality risk among US patients with metabolic syndrome. Sci Rep 15, 9589 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-94061-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-94061-7