Abstract

Differential equations-based epidemiological compartmental systems and deep neural networks-based artificial intelligence can effectively analyze and combat monkeypox (MPV) transmission with Poisson random measure noise into a stochastic SEIQR (susceptible, exposed, infected, quarantined, recovered) model human population and SEI (susceptible, exposed, infected) for rodent population. Compartmental models have estimates of parameter complications, whereas machine learning algorithms struggle to understand MPV’s progression and lack elucidation. This research introduces Levenberg Marquardt backpropagation neural networks (LMBNNS) in training, a new approach that combines compartmental frameworks with artificial neural networks (ANNs) to explain the complex mechanisms of MPV. Meanwhile, a model description proves the existence and uniqueness of a global positive solution. A threshold parameter is determined and employed to identify the factors that lead to infection in the general public. Furthermore, other criteria are developed to eliminate the infection within the entire population. The MPV is eliminated if \(\mathbb {R}_{0\textrm{h}}<1\), but continues if \(\mathbb {R}_{0\textrm{h}}>1\). The study depends on two functional scenarios to quantitatively clarify the theoretical results. An adapted dataset is generated employing the Adam algorithm to minimize the mean square error (MSE) by setting its data effectiveness to 81% for training, 9% for testing, and 10% for validation. The solver’s accuracy is validated by minimal absolute error and complementing responses to every hypothetical situation. In order to verify the adaptation’s reliability and precision, productivity is measured using the error histogram, changeover state, and prediction for addressing the MPV model. Visual representations are used to illustrate the investigation and compare results. Utilizing this hybrid approach, we want to increase our comprehension of disease propagation, strengthen forecasting competencies, and influence more efficient public health actions. The combination of stochastic processes and machine learning approaches creates a powerful tool for capturing the inherent uncertainties in infectious disease dynamics, as well as a more accurate framework for real-time epidemic prediction and prevention.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Recently, the viral infection identified as monkeypox was caused by the MPV, an element of the Orthopoxvirus family. This infection is primarily present in Central and West African countries, with isolated instances documented in other nations such as the United States and the United Kingdom1,2,3.

MPV is most commonly transmitted to individuals by intimate interaction via sick animals or pathogenic objects, including urine, blood, wounds, or matting1,2,4. Transmission from one individual to another is additionally probable, primarily via intimate personal contact involving affected people or contact to contaminated bloodstreams4. Indications of an MPV infection encompass a high temperature, a migraine and a distinctive pigmentation that progresses throughout the entire physique4. In serious instances, problems like a respiratory infection, septicaemia, and encephalopathy can develop2,3,4.

However, there is presently no particular antiretroviral therapy to treat MPV; nevertheless, medical assistance can help with alleviating symptoms and reducing the potential of complications4. The disease vaccination has been found to be beneficial for eradicating MPV, although it has ceased to be administered routinely1,2. As a result, safety precautions that involve interaction tracking, confinement, and segregation are critical for preventing transmission of illness3,4. MPV, a member belonging to the Orthopoxvirus family, was initially discovered in monkeys in the Central African Republic of the Congo in 1958, then among individuals in 1970. The viral infection is prevalent in regions of Central and West Africa, causing intermittent occurrences. Reports of incidents in non-African nations, such as the US, Spain, Portugal, and Spain, have lately escalated5 (see Figure 1 (a,b)).

Meanwhile, several methods are unable to account for the stochastic behaviors inherent in the MPV pandemic, which result from record oversights and time-varying transmission behavior. As a result, moving from deterministic to stochastic techniques is an immediate issue that coincides with the evolving context of disease modeling6,7. The Kalman filter is used in epidemiological modeling due to its ability to handle noisy data and provide scientific advantages in infectious disease contexts with intrinsic fluctuations and uncertainties. Additional research using Kalman filtering to assess the transmission of infectious diseases includes8,9. Such attempts mainly employ the extended Kalman filter to account for non-linearity caused by viruses in susceptible individuals. Several efforts have been made to eliminate the statistical implications associated with Kalman filters, using mathematical techniques from particle filtering. However, the possibility of severe infections leading to hospitalizations in the intensive care unit is addressed in10,11.

In addition to Kalman filters, continuous-time Markov chains are a popular stochastic methodology in research. They are commonly used to simulate epidemiological systems of modest complexity, which usually include two to four states12. Unlike our research, these models focus on certain epidemiological features such as illness extinction time, total number of infections/deaths, optimal revaccination time, and maximum infection cardinality. These schemes and stochastic epidemiological descriptors do not take into account hospitalizations, ICU admissions, or open population dynamics13. Papageorgiou and Vasiliadis14 presented the transient analysis of a SIQS model with state capacities using a non-homogeneous Markov system. Pérez et al.15 addressed a stochastic SVIR model with an imperfect vaccine and an external source of infection. Gamboa and Lopez-Herrero16 analyzed the effect of setting a warning vaccination level on a stochastic SIVS model with an imperfect vaccine.

(a) Geographical distribution of confirmed and suspected monkeypox cases during the outbreak (Diagram generated with Datawrapper) (see17) (b) The cumulative number of identified cases (by validation period) following the initial instance occurrence within the 2023 epidemic, as well as the entire amount of nations registering verified cases.

Recently, the initial MPV incidence in the United States was in 2003, when a West African visitor contracted the virus. This prompted an inquiry, which revealed 47 documented or suspected instances in six states, the majority of which were related to virus-infected prairie rodents. In 2003, Canada experienced an analogous occurrence involving two verified infections of MPV among travelers from West Africa18,19.

Portugal confirmed its initial MPV epidemic in 2018, including nine confirmed cases explained by current flights to Nigeria. In 2021, Spain reported an initial epidemic of MPV, involving two infections associated with excursions to Nigeria. The growing number of MPV infections away from Africa emphasizes the importance of regular monitoring and strategy to handle occurrences20.

To better understand the unpredictable behavior and prevention tactics of MPV, numerical modelling approaches21,22,23 are highly suggested. These systems use previous information to match actual with predicted disease results. Several MPV models, comprising single epidemic research to population threshold, have detected diverse epidemiological trends. External factors are constantly significant in both biological processes and physical catastrophes. Environmental factors strongly affect MPV propagation24. Outbreaks can be unpredictable due to unexpected behavioral connections and changing demographics. As a result, the randomness of the environment may significantly disrupt the infection profile. Modeling MPV employing techniques that consider alterations in the environment and interactions between individuals and rodents is crucial, as food and beverages and sexual contact are essential elements of the virus24,25.

Meanwhile, the scientific research on dynamical phenomena is substantial, and the underpinning structures have been extensively explained through a range of strategies, including deterministic and stochastic, fractional, and fractal-fractional methodologies26,27,28. Many deterministic frameworks were broadened using Gaussian noise and fractional formulations. The deterministic approach presupposes exclusively classical derivatives of the underlying parameters, but fractional formulations are freedom to choose any non-negative real number as an order. Modeling employing stochastic differential equations (DEs) is significantly more accurate than deterministic modeling using ordinary DEs or fractional derivatives29,30. Using stochastic DEs to evaluate an actual-life situation yields diverse outcomes. To gain greater comprehension, the framework must be simulated numerous repetitions based on the required average outcomes. Poisson random measure noise represents probably one of the most significant interruptions given that it operates as a threshold factor via drifting its speed. Introducing such noise into epidemiological algorithms offers trustworthy evidence that reveals previously unidentified details about the infection’s behavior. In particular, Poisson random measure noise offers considerable features versus Gaussian noise. Noise with Gaussian characteristics is often used in numerical modeling; however, it introduces unpredictability31,32,33. The proposed framework outperforms the broader Poisson random measure framework for neuronal effectiveness progression due to its incorporation of jumps that reduce Poisson random measure noise. The present investigation suggests that Poisson random measure noise is especially useful for epidemiological challenges where system reliability varies over time34,35.

Machine learning is becoming increasingly important in epidemiological modeling, particularly for instantaneous disease monitoring and intervention strategy. Research has shown that machine learning approaches, such as deep learning and analytical forecasting, can improve infectious disease outbreak predictions and understanding the spread mechanisms36,37.

Our research advances the prior research by using an amalgamation of Poisson random measure noise, ANN models and the LMBNNs38. This technique additionally enables an extensive investigation of MPV dissemination, but it also provides a scientific foundation that may be applied to various other transmissible illnesses. The incorporation of powerful machine learning methods in our study bridges a significant hole in existing epidemic investigations. Moreover, employing ANN algorithms, particularly LMBNN, to forecast MPV incidences in Portugal using data currently available39,40,41. Manohar et al.42 addressed hybridized long short-term memory-ANN-regularized self-organizing-based deep learning models for the prediction of COVID-19 cases in Eastern European countries. Lakshmi et al.43 investigated a new COVID-19 classification approach based on a Bayesian optimization vector machine kernel using chest X-ray datasets. Manohar and Das44 examined the comparison of hybrid artificial neural networks with GA, PSO, and RSA in predicting COVID-19 cases: a case study of India. Chandra et al.45 investigated ANN-based stock price prediction using the Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm. The contrasting perspectives of this country will enable medical professionals to develop adequate reaction plans. The present investigation is the initial endeavor to employ ANN for assessing current MPV incidents, providing useful insights into the phenomenon’s patterns. A time series dataset of MPV occurrences from Portugal, complemented by graphical representations of confirmed infections, is provided46. Manohar and Das47 demonstrated the prevalence and territorial illustration of documented reports of MPV via ANNs for the prediction of outbreak. Alpalhão et al.48 documented the viral genetic clustering and transmission dynamics of the 2022 MPV outbreak in Portugal.

The technique for forecasting is based on statistics collected by the “Our World in Data” website and employs neural network algorithms. The validity of the model is improved by the LMBNNS learning technique, which optimizes the number of neurones in a single hidden layer ANN model by cross-validation prior to stopping validation38. ANN-based regression techniques have demonstrated usefulness in identifying the propagation of transmissible illnesses such as MPV. These frameworks allow health care providers and politicians to exercise accurate choices about epidemic propagation or react appropriately to occurrences. ANN systems have shown effectiveness for time-series estimation across different fields49,50,51.

Inspired by the aforesaid discussion, the use of algorithms for learning in epidemiology studies constitutes a revolutionary technique for comprehending and controlling viral illnesses. Focusing on the prevailing state of the art in virus estimating, specifically the application of algorithms based on machine learning, our research attempts to improve the prediction modeling of MPV in the context of Poisson random measure noise. While previous investigations, such as47, have established NN algorithms for predicting MPV in multiple nations in a deterministic sense, the present study focuses on implementing the amalgamation of Poisson random measure noise with the LMBNN models to anticipate incidents of MPV in Portugal. By combining Lévy stochastic processes for modeling sudden, unpredictable events with LMBNN optimization for accurate parameter estimation, the most significant application is in modeling and predicting MPV outbreaks characterized by high variability, abrupt changes, and super spreading events. This hybrid methodology allows for more realistic and robust modeling of complex epidemiological dynamics, particularly in scenarios where traditional Gaussian-based stochastic models fall short. Also, this technique fills a gap in MPV studies and analyses the effectiveness of several NN models, adding insight to the epidemiology.

The comprehensive assumptions and modeling architecture are presented in the following order: Section 2 introduces the MPV framework and its hypotheses, as well as the significance of Poisson random measure noise. Moreover, it introduces significant terms and obstructions for stochastic modeling such as it evaluates the trustworthiness and positivity of the proposed solutions. In Section 3, we analyze the stochastic model solution’s behavior approaching the illness-free phase of the ordinary DEs framework and introduce the sickness extermination hypothesis and persistence of mean. Section 4 analyses stochastic and deterministic frameworks, including visualizations to confirm the mathematical findings. Section 5 presents the suggested LMBNNs approach and findings, followed by an interpretation grounded in computed consequences. In a nutshell, we culminate our effort by summarizing the research’s outcomes and proposing future research avenues in conclusion.

Model description

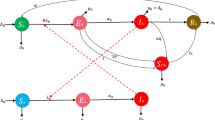

Considering the propagation behavior of MPV, including two populations-rodents and humans-we suggest a deterministic compartmental model. Five categories make up the human population: susceptible humans \({S}_{\textrm{h}}(\xi )\), exposed humans \({E}_{\textrm{h}}(\xi )\), infected humans \({I}_{\textrm{h}}(\xi )\), isolated humans \({Q}_{\textrm{h}}(\xi )\) and recovered humans \({R}_{\textrm{h}}(\xi )\). Three compartments comprise the rodent population: susceptible rodents \({S}_{\textrm{r}}(\xi )\), exposed rodents \({E}_{\textrm{r}}(\xi )\) and infected rodents \({I}_{\textrm{r}}(\xi )\). The rate of human recruitment into the general population is \(\omega _{\textrm{h}}\). The successful interaction rate and probability of an individual apprehending an infection via a diseased rodent are illustrated by \(\eta _{1}\) and the probability of a person contracting MPV following contact with an infectious human is represented by \(\eta _{2}\). \(\psi _{2}\) represents the proportion of affected people who advance to the severely infected class, while \(\psi _{1}\) is the proportion identified. Upon diagnosis, certain suspected instances are verified by medical professionals. whereas undiagnosed cases revert to the susceptible human rate at \(\phi\). A rate of \(\lambda\) is used to treat suspected cases and transfer them to the recovered class. Humans recover at a rate of \(\gamma\). A rodent’s risk of contracting an infection per encounter with an infected rodent is determined by its effective contact rate, or \(\eta _{3}\). The natural mortality rate \(\mu _{\textrm{r}}\) or the death rate brought on by the illness \(\rho _{\textrm{r}}\) reduces the number of diseased rodents. The recruitment rate of rodents into the general public is \(\omega _{\textrm{r}}\). The classical model presented in Figure 2 used in studying the dynamics of MPV transmission in this work is influenced by the subsequent model of nonlinear ordinary DEs in (1). The state variables and parameters of the model are given in Table 1 as:

Schematic flow of MPV model (1).

By implementing initial conditions \({S}_{\textrm{h}}(0)>0,~ {E}_{\textrm{h}}(0)>0, ~{I}_{\textrm{h}}(0)>0,~ {Q}_{\textrm{h}}(0)>0, ~{I}_{\textrm{h}}(0)>0,~ {S}_{\textrm{r}}(0)>0,~ {E}_{\textrm{r}}(0)>0, ~{I}_{\textrm{r}}(0)>0.\) For the human population, \(\bar{\Upsilon }_{\textrm{h}}={S}_{\textrm{h}}+{E}_{\textrm{h}}+{I}_{\textrm{h}}+{R}_{\textrm{h}}+{I}_{\textrm{h}}\). Also for rodent population, \(\bar{\Upsilon }_{\textrm{r}}={S}_{\textrm{r}}+{E}_{\textrm{r}}+{I}_{\textrm{r}}\). Now, we convert the classical MPV model to a stochastic version as follows:

Despite the aforementioned qualities of the Poisson random measure disturbances, it may be additionally advantageous whenever the noisy-scaled drift speed occurs inside an appropriate range of its threshold levels. The incorporation of each non-local and local Lipschitz criteria means that incorporating Poisson random measure disturbances could enhance the transmitted data or bit content in an assortment of feedback-related outbreaks that adopt a particular, arbitrary stochastic DE. In accordance with literature52,53, Poisson random measure noise provides strengths over ordinary Gaussian noise in conceptual epidemiological frameworks. However, it additionally introduces greater computational intricacy to the subject under discussion. Jump-diffusion Poisson random measure noise improves the traditional Poisson random measure hypothesis by accurately explaining the emergence of a neurone’s potential at its membrane. Poisson random measure noise increases the reliability of time-dependent recurrent NNs. Implementing stochastic Poisson random measure noise to the framework (2) results in an accumulation of Poisson stochastic DEs54:

whereas

The compensated Poisson random measure indicated by \(\bar{\Upsilon },\) it can be described as \(\bar{\Upsilon }(d\xi , d t ) = \Upsilon (d\xi , d t )-\chi (d\xi ) d\Psi\). The expression \(\mho (\xi )\) represents the left limit. All additional components retain the identical interpretation. Here, \(\bar{\Upsilon }\) represents the Poisson random measure and \(\chi (.)\) is its intensity measure. Also, the mapping \(\chi\) stated on measure set \(\Psi [0, \infty )\) possessing the features \(\chi (\Psi )<\infty\) and \(\mho _{\textsf{i}}\ge 0,~(\textsf{i} = \{1, 2,...,8\})\).

Basic Concept

This part includes fundamental descriptions and Lemmas in stochastic significance. The formatting utilized herein corresponds with the version supplied in55, and will therefore be implemented within the work.

Lemma 1

To facilitate our investigation, we shall employ two essential presumptions, denoted \(\textbf{A}_1(\xi )\) and \(\textbf{A}_2(\xi )\). Such hypotheses are crucial for demonstrating the existence and uniqueness of a global non-negative solution to the framework (3)56,57.

\(\textbf{A}_1(\xi ).~~ \forall ~~ \textrm{M}> 0~~ \exists ~~ \mathbb {L}_\textrm{M} > 0\) such that

with \(|\textrm{w}_1| \vee |\textrm{w}_2| \le \textrm{M},\) where

where \(\Xi\) represents the compensated stochastic parameter.

\(\textbf{A}_1(\xi ).~~ |\log (1 + \mho _{\textsf{i}}(\textrm{w}))| \le \complement\) for \(\mho _{\textsf{i}}(\textrm{w}) > -1, \textsf{i} = \{1, 2,..,8\},\) where \(\complement\) is a fixed non0negative number.

Theorem 1

If for stochastic model (3) \(({S}_{\textrm{h}}, {E}_{\textrm{h}}, {I}_{\textrm{h}}, {Q}_{\textrm{h}}, {R}_{\textrm{h}}, {S}_{\textrm{r}}, {E}_{\textrm{r}}, {I}_{\textrm{r}})\) is a solution containing initial values \(({S}_{\textrm{h}}(0), {E}_{\textrm{h}}(0), {I}_{\textrm{h}}(0), {Q}_{\textrm{h}}(0), {R}_{\textrm{h}}(0),\) \({S}_{\textrm{r}}(0), {E}_{\textrm{r}}(0), {I}_{\textrm{r}}(0)) \in \mathbb {R}_{8}^{+}\), then

Moreover, if \(\max (\mu _{\textrm{h}}, \mu _{\textrm{h}})>\frac{\varrho _{1}^2+\varrho _{2}^2+\varrho _{3}^2+\varrho _{4}^2+\varrho _{5}^2+\varrho _{6}^2+\varrho _{7}^2+\varrho _{8}^2}{\xi },\) then

Thus, the solutions of MPV model (3) possess the subsequent features;

Proof

The documentation regarding the Lemma are analogous to those supporting Lemmas 1 and 258, thus we will overlook them when examining this setting. \(\square\)

The aforementioned descriptions of mean persistence are noteworthy pointing out, as stated in55.

Definition 1

(59) For stochastic model (3) to demonstrate the attribute of resilience or persistence, it needs to meet the subsequent requirements:

Analogue to the preceding requirement, the Lemmas used in55 must be valid for MPV endurance.

Lemma 2

(Strong law) (59) Considering a real-continuous mapping \(\mathbb {M} = \{\mathbb {M}\}_{0\le \xi }\), the local martingale criterion occurs if it disappears as \(\xi \rightarrow 0\) and

Lemma 3

Assume that \(\textrm{h} \in \complement ([0, \infty ) * \bar{\textrm{B}}(0, \infty ))\) and \(\textrm{G} \in \complement ([0, \infty ) * \bar{\textrm{B}}\mathbb {R}) \ni \lim _{\xi \rightarrow \infty } \frac{\textrm{G}(\xi )}{\xi }=0,~a.s.\) if \(\xi \ge 0\)

Therefore, we have

Herein, \(\Lambda\) and \(\Lambda _0\) indicate positive constants, respectively.

Global positive solution

Stochastic model (3) is a physiological analogy for the population dynamics problem that necessitates a global, bounded, positive solution. The following result will examine the well-posedness of the system defined by stochastic model (3). To facilitate our analysis, we will utilize the two common hypotheses, \(\textbf{A}_1\) and \(\textbf{A}_2\), which are outlined in Lemma 1. In order to prove that there is a unique global solution for stochastic model (3), certain presumptions are essential.

Theorem 2

Suppose that a stochastic model (3) for \(\xi \ge 0\) possess only one solution \(({S}_{\textrm{h}}(\xi ), {E}_{\textrm{h}}(\xi ), {I}_{\textrm{h}}(\xi ), {R}_{\textrm{h}}(\xi ), {Q}_{\textrm{h}}(\xi ), {S}_{\textrm{r}}(\xi ), {E}_{\textrm{r}}(\xi ), {I}_{\textrm{r}}(\xi ))\) for any initial value \(({S}_{\textrm{h}}(0), {E}_{\textrm{h}}(0), {I}_{\textrm{h}}(0), {R}_{\textrm{h}}(0), {Q}_{\textrm{h}}(0), {S}_{\textrm{r}}(\xi , {E}_{\textrm{r}}(\xi ), {I}_{\textrm{r}}(\xi )) \in \mathbb {R}_8^+\) and the solution will exist in \(\mathbb {R}_8^+\) containing unit probability, \(({S}_{\textrm{h}}(\xi ), {E}_{\textrm{h}}(\xi ), {I}_{\textrm{h}}(\xi ), {R}_{\textrm{h}}(\xi ), {Q}_{\textrm{h}}(\xi ), {S}_{\textrm{r}}(\xi ), {E}_{\textrm{r}}(\xi ), {I}_{\textrm{r}}(\xi )) \in \mathbb {R}_8^+ ~~\forall ~ \xi \ge 0,\) a.s.

Proof

Since the drift and diffusion are guaranteed to be locally Lipschitz by the requirement \(\textbf{A}_1\), there will be a time \(\xi\) at which the suggested concern will have a locally specific solution in the range \([0, \lambda _{\mathfrak {e}})\). The explosion phase is represented here by \(\lambda _\mathfrak {e}\); researchers are directed to55 for more details. To establish that the outcome is global, it need to be shown that \(\lambda _{\mathfrak {e}}= \infty\) is adequate. In order to illustrate this, let \(\mathbb {K}_0\) be a sufficiently large positive real integer such that every scheme solution falls inside the range \([\frac{1}{\mathbb {K}_0}, \mathbb {K}_0]\). As a result, given \(\mathbb {K} \ge \mathbb {K}_0\), permit

where \(\textrm{W} = ({S}_{\textrm{h}}(\xi ), {E}_{\textrm{h}}(\xi ), {I}_{\textrm{h}}(\xi ), {Q}_{\textrm{h}}(\xi ), {R}_{\textrm{h}}(\xi ), {S}_{\textrm{r}}(\xi ), {E}_{\textrm{r}}(\xi ), {I}_{\textrm{r}}(\xi ))\). In this study, the\(\inf\) of an empty set is denoted by \(\inf \emptyset = \infty\). Here, \(\lambda _{\mathbb {K}}\) increases as \(\mathbb {K}\rightarrow \infty\). Suppose that \(\lambda _{\mathbb {K}}\) possesses a limit of \(\lambda _{\infty }\), It is almost a given that \(\lambda _{\infty } \le \lambda _{\mathfrak {e}}\). Alternatively, it is necessary to demonstrate that \(\lambda _{\infty } = \infty\). If this supposition is false, then the constants \(\textsf{T}>0\) and \(\varepsilon\) lie in (0,1) such that

Hence, there is a natural number \(\mathbb {K}_1 \ge \mathbb {K}_0\), the following holds

To demonstrate the additional part of the hypothesis, proceed to construct the mapping as:

The aforementioned connection defines the \(L\mathbb {U}\) operator from \(\mathbb {R}^{8}_+\) to \(\mathbb {R}_+\) as:

Consider \(\eta =\max \{\eta _{1},\eta _{2}, \eta _{3}\}\). Furthermore, (13) ensures the inequality \({S}_{\textrm{h}}+{E}_{\textrm{h}}+{I}_{\textrm{h}}+{Q}_{\textrm{h}}+{R}_{\textrm{r}}+{S}_{\textrm{r}}+{E}_{\textrm{r}}+{I}_{\textrm{r}}\le 1,\) thus

The remaining portion of the demonstration basically follows the demonstration of Theorem 2.1 of55,60. As a consequence, we will eliminate it in here, putting the hypothesis’s argument to a conclusion. \(\square\)

Extinction and persistence of disease

The following subsection presents advantageous factors for the eventual demise of the MPV in the community. Our focus is mostly on the foreseeable behaviour of the proposed response. Our approach commences with establishing the framework’s criteria number and then stating a result for infection eradication. This formula gives a threshold value for the stochastic model:

Theorem 3

Let \(({S}_{\textrm{h}}, {E}_{\textrm{h}}, {I}_{\textrm{h}}, {Q}_{\textrm{h}}, {R}_{\textrm{h}}, {S}_{\textrm{r}}, {E}_{\textrm{r}}, {I}_{\textrm{r}})\) be the solution of stochastic model (3) with initial conditions. If \(\mathbb {R}_{0\textrm{h}}<1,~ \mathbb {R}_{0\textrm{r}}<1\), then the subsequent characteristics of such a model solution must exist:

In simple terms, the preceding indicates the eventual demise of the MPV in the society having probability one.

Proof

After performing the integration on model (3), the subsequent formulae can simply be generated:

Employing the second-last equation in problem (20), one can easily compute

where

For the human infected population employing Itô’s technique, the third equation of (20) yields after simplification:

Applying integration on (24) from 0 to \(\xi ,\) and dividing by \(\xi\) provides the subsequent relation:

By replacing (22) with (25), we obtain

Furthermore, \(\textsf{M}_{\textsf{i}}(\xi ) = \frac{\textsf{a}_{\textsf{i}}}{\xi }\int _{0}^{\xi }d\textrm{B}_\textsf{i}{\xi }\) for \(\textsf{i} = \{1, 2, ..,5\}\) are the martingale operator disappears for \(\xi = 0\). Applying \(\xi \rightarrow \infty\) and utilizing Lemma 3, one obtains

Whenever \(\mathbb {R}_{0\textrm{h}} < 1\), (25) generates

Accordingly, (28) assures

Considering equation (29) in (22) and keep in view \(\lim _{\xi \rightarrow \infty }\sup \int _{0}^d\textsf{M}_\textsf{i}{\xi }=0\), we get

Also, for the rodent infected population using Itô’s formula, last-equation of (20) yield after simplification:

Integrate (31) from 0 to \(\xi ,\) then dividing by \(\xi ,\) gives

Furthermore, \(\textsf{M}_{\textsf{i}}(\xi ) = \frac{\textsf{a}_{\textsf{i}}}{\xi }\int _{0}^{\xi }d\textrm{B}_\textsf{i}{\xi }\) for \(\textsf{i} = \{6,7,8\}\) are the martingale mapping vanishes for \(\xi = 0\). Employing \(\xi \rightarrow \infty\) and considering Lemma 3, we find

For \(\mathbb {R}_{0\textrm{r}} < 1\), related (32) yields

with the similar approach, we get

Adopting the same technique, we can prove

This yields the intended outcome. \(\square\)

The following part will explore the future viability of the MPV in the general population. In order to be more particular, we will examine the requirements of the settings that ensure infection perseverance, which is necessary prior to implementing a successful surveillance strategy. We shall commence by investigating the idea of average perseverance, as explained in55.

Theorem 4

Assume that the stochastic model (3) is considered persistent in the mean if:

where

and it ensures that the illness will always occur in the community irrespective of \(\xi\). Introducing

Proof

Assume that there are functions \(\textbf{G}_1\) and \(\textbf{G}_2\) for human and reservoir hosts, respectively, defined as:

where \(\mathcal {Q}_{\jmath },~(\jmath =1,..,7)\) are real constants and will be determined later. Applying the Itô formulation to relation (40) and (41), we get

After simplification, we get

For brevity, assume that

Utilizing these \(\textrm{w}_{\textsf{i}}\), we have

Integrating both sides of the stochastic MPV model (3) and replacing (45) into (40) and (41), we have

Applying strong law defined in Lemma 2, we get

Now, by utilizing Lemma 3, the inferior limit of relationship (46,47) is provided by we obtain

likewise, \(\lim \inf _{\xi \rightarrow \infty }\langle {I}_{\textrm{h}}\rangle \ge 0\) and \(\lim \inf _{\xi \rightarrow \infty }\langle {I}_{\textrm{r}}\rangle \ge 0\).

These outcomes constitute the demonstration of Theorem 4. \(\square\)

Numerical simulations

The following part discusses the implementation of representations to confirm mathematical findings and predict disease behavior within different scenarios. To develop an algorithm for a computationally solvable problem (3), we used the traditional numerical methodology described in61. To effectively design the method, we used \(\textbf{m} = 0, 1, 2, ..., \textbf{M}^{*}\), where \(\textbf{M}^{*}\in \Upsilon\) and \(\textrm{w}^{*}\in \textsf{Y}.\) We take into consideration a fixed step size \(\Theta \xi = \frac{\textrm{T}}{\Upsilon }\) in order to characterize the time interval \([0,\textrm{T}]\). Also, for \(\textsf{i} \in \{1,2,...,8\}\) and \(\Upsilon _{\textrm{h}}^{\textbf{m}}={S}_{\textrm{h}}+{E}_{\textrm{h}}+{I}_{\textrm{h}}+{R}_{\textrm{h}}+{I}_{\textrm{h}}\). Moreover, concerning the rodent density \(\Upsilon _{\textrm{r}}^{\textbf{m}}={S}_{\textrm{r}}+{E}_{\textrm{r}}+{I}_{\textrm{r}}\) and \(\Theta \mathbb {Z}_{\textsf{i}\textbf{m}} \Theta _{\approx } \mathcal {W}(\xi _{\textbf{m}}+1)- \mathcal {W}(\xi _{\textbf{m}}) = \sqrt{\Theta \xi }\varrho _{\textsf{i},\textbf{m}}\), where \(\varrho _{\textsf{i},\textbf{m}}\) indicates the Gaussian noise pertaining to distributions \(\Upsilon (0, 1)\). Furthermore, \(\Theta L _{\textsf{n}}\) stated as \(L (\xi _{\textsf{n}}+1) - L (\xi _{\textsf{n}})\), as a Poisson distribution possessing intensity \(\chi\) taking into account \(\Phi\) = \((0, +\infty )\) with \(\chi (\Phi ) = 1\). The Milstein technique for numerically solving the framework (3) is as follows:

To configure numerical results for the framework (3), consider using the positive preserving truncated Euler-Maruyama (PTEM) approach62, as well as alongside the aforesaid strategies. Numerous researchers have utilized positive PTEM techniques to study complex physical mechanisms63. This strategy was chosen due to its ease of use and effectiveness for managing Poisson random measure jumps.

The model (3) requires specific parameter settings in order to quantitatively substantiate the mathematical findings. Two different sets of input values, shown in Table 2, were employed to simulate the framework. These categories additionally encompass the first demographics of individuals and rodents. For each value combo, the framework was emulated throughout the time interval [0, 100] and every feature was explored with extensive visual demonstrations.

The incidence rate and parameter estimation

MPV indications, such as occurrence, prevalence, and fatality rates, are frequently utilized to evaluate the load of disease produced by MPV. The occurrence rate is a key metric tracked and reported by global officials. The rate of infection is estimated based on both new and relapsed MPV infections. The prevalence rate is expressed as the number of new viral infections per 100,000 individuals annually64 as:

The model parameters were derived based on the prevalence rates of persistent MPV in Portugal, as reported in the WHO annual MPV report65. Some data were sourced from previous research. The values of all parameters determined by the curve fitting procedure (see Figure 3)(a) are denoted as “fitted” in the corresponding column of Table 2. We employed Latin hypercube sampling to estimate the parameter range and varied the initial feature collection at the same time. The framework was used to analyze the prevalence rate for every value variation inside the analyzed region. The Euclidean distance decrease approach selects the settings that best fit the WHO prevalence information.

However, the initial MPV infections in Portugal appeared laboratory-confirmed on May 17, 2022, and the pandemic occurred about July 17, 2022, with a subsequent decrease in the overall number of patients. As of January 10, 2023, there were 951 documented incidences in Portugal (Fig. 3)(b). To better comprehend the biological dynamics of MPV in Portugal amid the 2022 multi-country epidemic, infectious sequencing results have been analysed from 495 people who tested confirmed using polymerase chain reaction. The random sample accumulation originated for the 495 identified instances varied from 4 May (ISO week 18) to 16 September (week 37) 2022, indicating a large pattern collection of 54.2% (495 versus 914) overall demonstrated mpox scenarios in Portugal throughout that time (which corresponds to 52.1% of the total reported scenarios up to 10 January 2023) (Fig. 3).

(a) Parameter prediction: The black dots depicts the WHO prevalence rate65, whereas the red curve represents the fitted curves for Portugal from 17 May 2022 and 10 January 2023. (b) As of January 10, 2023, there were cumulative and weekly occurrences of MPV, as well as infectious in Portugal. The bars show the distribution of MPV positive data by collecting date (week) and are color-coded based on virus accessibility. The line that is dashed indicates the overall amount of cases.

Numerical findings for extinction

In previous subsections, we studied the factors that lead to virus extinction in populations and those that promote long-term persistence. Theorem 3 was proven using the constraints \(\mathbb {R}_{0\textrm{h}} < 1\) and \(\mathbb {R}_{0\textrm{r}} < 1\). The theory offers a biological explanation for the unit probability of MPV eradication in both human and rodent populations when the required conditions are met. Despite the extraordinarily high rate of initial infection, the disease will be completely eliminated from the populace. To quantitatively evaluate these truths, we developed a model depends on Example 1 and provided graphical illustrations in Figure 2. The random system produces curves that are easily observed to progressively tend to the disease-free condition of the associated deterministic system.

Example 1

In this instance, the parameter values for Case I are derived from Table 2. These parameter values are used to construct the threshold parameter \(\mathbb {R}_{0\textrm{h}}\)=0.048 and \(\mathbb {R}_{0\textrm{r}}\)=0.053, which comes out to be smaller than unity. As a result, Theorem 3 requirements are satisfied, which brings about the obvious conclusion. Consequently, each component of the model’s solution complies with the following expressions:

These variations demonstrate the disappearance of the virus throughout the general population, and Fig. 4 (a-h) statistically supports these findings. The results of the analysis on extermination are currently verified and can be considered trustworthy.

This scenario exhibits stochastic extinction, in which the solutions converging to completely eradicate the infection. This behavior is similar for all pathways, influenced by noise-free and standard. Another noteworthy fact is the significant difference in extinction rates between pathways driven by Poisson random measure noise and those following ordinary leaps. Poisson random measure noise trajectories have faster extinction rates than conventional jumps.

Numerical simulations are conducted for three different case classifications matching the framework (4). These categories include the following: (1) deterministic case; (2) Gaussian white noise; (3) Poisson random measure noise.

Numerical description for persistence

In this section, we also try to measure the disease’s persistence in humans and rodents. Theorem 4 theoretically explains the average prevalence of virus in the populations during time \(\xi\). The conclusion follows if the supposition is true, according to the Theorem 4. We looked at data from Table 2 Case II to show the theorem’s numerical verification and we discovered that \(\mathbb {R}_{0\textrm{h}}^{\textrm{s}}>1\). These data were used to simulate both the stochastic and deterministic models; the outcomes are shown in Figure 5 (a-h). The depiction shows that as long as the threshold is greater than one, the MPV is likely to persist in both populations. Therefore, in these situations, the interested parties need to find a control program to manage the infection.

Numerical simulations are conducted for three different case classifications matching the framework (3). These categories include the following: (1) deterministic case; (2) Gaussian white noise; (3) Poisson random measure noise.

Example 2

(The impact of \(\eta _{1}\) , \(\eta _{2}\) and \(\eta _{3}\))

The behavior of the mechanism is mostly determined by a value of \(\eta\). It has an impact on the procedure’s general dependability and convergence. We took into consideration the settings of the characteristics in Table 2 Case III in order to demonstrate the impact of \(\eta _{1}\), \(\eta _{2}\), and \(\eta _{3}\) on the dynamical patterns of the MPV. Figures 6 (a-h) and 7 (a-h), which were produced by modeling the stochastic framework, show the dynamic behavior of outbreaks. In the appropriate communities, decreasing the concentrations of \(\eta _{1}\), \(\eta _{2}\), and \(\eta _{3}\) speeds up the eradication of infection. These criteria must be lowered in order to encourage the elimination of disease. Moreover, the simulations demonstrate that a deeper comprehension of the disease’s processes requires the inclusion of nonlinear stochastic disturbances.

Numerical simulations are conducted for three different case classifications matching the framework (3). These categories include the following: (1) deterministic case; (2) Gaussian white noise; (3) Poisson random measure noise; for \(\eta _{1}\) = 0.5; \(\eta _{2}\) = 0.9; \(\eta _{3}\) = 0.9.

Numerical simulations are conducted for three different case classifications matching the framework (3). These categories include the following: (1) deterministic case; (2) Gaussian white noise; (3) Poisson random measure noise; for \(\eta _{1}\) = 0.3; \(\eta _{2}\) = 0.45; \(\eta _{3}\) = 0.70.

Proposed schemes: LMBNN approach

Here, the LMBNN approach is described in two parts for solving the MPV system. The non-linear MPV model (3) is employed for implementing the LMBNN operator efficiency and network architecture. Table 3 provides particular input settings to execute the mathematical operations. The source data collection for the suggested LMBNN can be created using MATLAB-PDEs-solver and the Adams-Bashforth technique. The MPV model’s numerical outcomes are analyzed employing the LMBNN technique, which has 15 neurons and information choice rates of 81%, 9% and 10% for training, testing, and validation. Figure 8(a,b) depicts the configuration of concealed, input, and output neurons for layers and network form.

Now the computational findings for three MPV models utilizing the LMBNN approach are presented. The suggested approach was utilized to address the framework for multiple scenarios and the starting point. These scenarios provide an extensive representation of model 3 for implementing the suggested method and analyzing results. Now by considering Case I in Table 2.

Outcomes assessment for Case I

Figures 9(a) and 9(b) show the mean square error and transitional state findings associated with the MPV model (1), respectively. Figure 9(c) shows the process of convergence evaluation for Case I, including MSE for testing, training and validation. The MPV system converges at \(10^{-13}\) in Case I. Figure 9(b) displays the gradient and step dimension h in Case I. The gradient for Case I is \(9.6458\times 10^{-8}\) with a step size of \(10^{-13}\). Figures 9(c) and 9(d) show the effectiveness of the suggested LMBNN strategy for the MPV model in Case I and error histograms, respectively. Figure 9(a) shows the greatest efficiency for Case I at \(2.95\times 10^{-13}\). The suggested approach performs effectively at 38 epochs. Error histograms show zero errors within \(-1.5\times 10^{-7}\) and \(1.48\times 10^{-7}\) (see Figure 9(d)). This suggested LMBNN approach clearly validates the obtained results.

Figure 10 shows the regression curve for Case I utilizing the suggested LMBNN approach for the MPV model. Correlations of R have a value of unity, validating the precision of the validation, testing and training procedures. The corresponding regression figure for Case I demonstrates the optimal operating situation of the MPV model (3).

Graphical depiction for Case I for MSE, STs, results and EHs performances for MPV model (3).

Regression analysis of Case I for MPV model (3).

Outcomes assessment for Case II

Figures 11(a) and 11(b) show the mean square error and transitional state findings of the MPV model (3), respectively. Figure 11(c) shows the convergence evaluation of the mean square error for the Case II procedures of training, evaluation, and verification. The confluence of MPV is discovered at \(10^{-13}\) in Case II. Figure 11(b) displays incline and increment measurement Mu for Case II. The gradient for Case II is \(9.9354\times 10^{-8}\), with an increment of \(10^{-14}\).

Figures 11(c) and 11(d) show the effectiveness of the suggested LMBNN strategy for the MPV model in Case II and the error histogram, respectively. Figure 11(a) shows the greatest efficiency for Case II at \(2.32\times 10^{-13}\). It is important to highlight that error histograms display no inaccuracies at \(-3.8\times 10^{-8}\). The suggested LMBNN approach validates the result attained. The suggested framework performs optimally at 44 epochs.

Figure 12 shows the regression curve for Case II with the suggested LMBNN approach for the MPV model. Correlations of R data have been determined to be unity, validating the precision of data utilized in training, testing, and validation. The regression plot for Case II shows that the MPV model works perfectly.

Graphical depiction for Case II for MSE, STs, results and EHs performances for MPV model (3).

Regression analysis of Case II for MPV model (3).

Outcomes assessment for Case III

Figures 13(a) and 13(b) show the means square error and transitional state findings of the MPV model (3), respectively. The convergence evaluation using MSE for training, testing and validation is described. Figure 13(c) shows the convergence evaluation of the MSE in training, testing and validation in Case III. The confluence of MPV was discovered at \(10^{-13}\) in Case III. Figure 13(b) displays the incremental length Mu and a transition for Case III. The gradient for Case III is \(9.9569\times 10^{-8}\), with a step size of \(10^{-14}.\) Figures 13(c) and 13(d) show the efficacy of the suggested LMBNN strategy using the MPV model in Case III with error histogram, respectively. Figure 13(a) shows the greatest efficiency for Case III at \(1.856\times 10^{-13}.\) It is important to highlight that error histograms show inaccuracies at \(-1.8\times 10^{-8}\). This suggested LMBNN approach validates the result attained. The suggested framework performs optimally at 34 epochs. Figure 14 shows the regression curve for Case III with the suggested LMBNN approach for the MPV model. Correlations of R show unity, validating the preciseness of data employed in training, testing, and validation operations. The regression plot for Case III demonstrates the optimal operating setting for the MPV model (3).

Graphical depiction for Case III for MSE, STs, results and EHs performances for MPV model (3).

Regression analysis of Case III for MPV model (3).

Performance comparison for MPV model

Figures 15 illustrate the implementation of outcome evaluations and AE criteria in LMBNN processes to address the MPV model. Figures 15 confirm the AE results for \({S}_{\textrm{h}}(\textrm{t})\), \({E}_{\textrm{h}}(\textrm{t})\), \({I}_{\textrm{h}}(\textrm{t})\), \({Q}_{\textrm{h}}(\textrm{t}),\) \({R}_{\textrm{h}}(\textrm{t}),\) \({S}_{\textrm{r}}(\textrm{t}),\) \({E}_{\textrm{r}}(\textrm{t})\) and \({I}_{\textrm{r}}(\textrm{t})\) employing the LMBNN approach. Figure 15 (a) displays the AE measurements for each susceptible humans. The mathematical framework for all three situations uses \({S}_{\textrm{h}}(\textrm{t})\) values ranging from \(10^{-4}\) to \(10^{-5}\). Figure 15 (b) shows the AE statistic for exposed humans, with \({E}_{\textrm{h}}(\textrm{t})\) ranging from \(10^{-5}\) to \(10^{-6}\). This simplifies the framework for three instances. Figure 15 (c) depicts AE for infected humans. \({I}_{\textrm{h}}(\textrm{t})\), fluctuates from \(10^{-4}\) to \(10^{-6}\) for three different cases of the mathematical models of the MPV. Figure 15 (d) shows that the AE estimates for the quarantine humans range between \(10^{-3}\) to \(10^{-6}\). Figure 15 (e) depicts AE for populations who have recovered. The mathematical framework is solved with \({R}_{\textrm{h}}(\textrm{t})\) values ranging from \(10^{-3}\) to \(10^{-6}\). Three compartments comprise the rodents population: as Figure 15 (f) depicts AE for susceptible rodents. \({S}_{\textrm{h}}(\textrm{t})\), fluctuates from \(10^{-3}\) to \(10^{-6}\) for three different cases of mathematical models of the MPV. Figure 15 (g) shows that the AE estimates for the exposed rodents \({E}_{\textrm{r}}(\textrm{t})\) range between \(10^{-4}\) to \(10^{-6}\). Figure 15 (h) depicts AE for populations of infected rodents \({I}_{\textrm{r}}(\textrm{t})\). The AE illustrations confirm the accuracy of the LMBNN techniques in solving the mathematical framework of the MPV model. Table 4 shows system convergence by intricacy, MSE, training, authentication, generation, and testing. Table 4 shows the optimal effectiveness and gradient attained with the suggested LMBNN approach. The compiled result collection includes information on processing cost, epochs and time increment for all three scenarios.

AE performance of the MPV model (3).

Absolute error of MPV model

Figures 16 compare the outcomes of every case using comparative sources of data for five categories make up the human population (\({S}_{\textrm{h}}(\xi )\),\({E}_{\textrm{h}}(\xi )\),\({I}_{\textrm{h}}(\xi )\),\({Q}_{\textrm{h}}(\xi ),\) \({R}_{\textrm{h}}(\xi ))\). Three compartments comprise the rodent population (\({S}_{\textrm{r}}(\xi )\),\({E}_{\textrm{r}}(\xi )\),\({I}_{\textrm{r}}(\xi )\)), respectively.

Figure 16(a) depicts the vulnerable component of the MPV model. This paper compares the results supplied by the Adams technique to the results for the three situations acquired using the suggested LMBNN technique. The analysis confirms and validates the suggested LMBNN strategy. However, case I had a greater proportion of susceptible humans to the MPV than cases II and III. Case III demonstrates the lowest protective precaution for those susceptible humans to MPV.

Figure 16(b) compares the produced comparison evidence with the results attained using the suggested LMBNN strategy. The overall incidence of exposed humans decreases significantly after the first case. The comparison figure shows that case I leads to a faster decline in exposed humans utilizing the MPV model than cases II and III, respectively.

Figure 16(c) shows an analysis of infected humans among various cases. Increased contact leads to a higher prevalence of MPV infection. Case III has fewer MPV infectious, while Case I has the most.

Figure 16(d) compares the source information to the suggested scheme’s outcomes for the quarantine population in three scenarios. Case I formulations result in higher MPV among the population. Cases II and III show a slower rate to the MPV, resulting in fewer quarantine populations.

Figure 16(e) compares the source information to the suggested scheme’s outcomes for the recovered population in three scenarios. Case I formulations result in higher MPV recovery rates among the population. Cases II and III show a slower immune response to the MPV, resulting in fewer recovered populations.

Figure 16(f) depicts the susceptible rodents of the MPV model. The analysis confirms and validates the suggested LMBNN strategy. Case I had a lower proportion of susceptible rodents to the MPV than cases II and III. Case III demonstrates the highest protective precaution for those susceptible rodents to MPV.

Figure 16(g) compares the produced comparison evidence with the results attained using the suggested LMBNN strategy. The overall incidence of exposed rodents decreases significantly after the first case. The comparison figure shows that case I leads to a faster decline in exposed rodents utilizing the MPV model than cases II and III, respectively.

Figure 16(h) shows an analysis of infected rodents among various cases. Increased contact leads to a higher prevalence of MPV infection. Case III has fewer MPV infectious, while Case I has the most.

Comparison of the effectiveness of the classical MPV model (3).

Experiments and their consequences

Epidemics, particularly the emerging MPV, pose significant challenges to national healthcare structures worldwide. Mathematical modeling of transmissible illnesses frequently involves deterministic strategies that extend the conventional SIR model with differential equations for exposed and died patients. The deterministic approaches to MPV are insufficient to account for the complicated dynamics of the disease66. Model parameters change dramatically with health restrictions like quarantine and masks, as well as the formation of variations. The reported data has uncertainty due to the difficulty of detecting asymptomatic illnesses and the PCR test’s erroneous positive-negative ratio. As a result, we explore designing a dynamic model capable of managing these changes. This work presents a hybrid SEIQR model with dynamic parameter evaluation. It addresses the limitations of deterministic compartmental models66 and significantly improves predictive capacity. We expand the basic SIR model with eight differential equations to account for susceptible humans, exposed humans, infected humans, isolated humans, recovered humans, susceptible rodents, exposed rodents and infected rodents. Incorporating quarantine into the model provides significant advantages. Given the prevalence of untreated persons in MPV, daily operational and recovered cases may not accurately reflect the outbreak’s progression. Individuals treated by quarantine are rigorously screened for MPV infection, making routine observations the most trustworthy evidence to assess the offered model’s fit-predictive potential.

This article proposes an enlarged compartmental version of the classical SEIR model that includes states with relevant daily observations. Our Lévy stochastic epidemiological model improves its fitting and predictive ability by utilizing advantageous daily observations. The Poisson random measure technique uses daily observations to analyze parameter fluctuation, resulting in a stochastic strategy. Using model parameters in screening allows us to track changes during outbreaks.

Our model’s accuracy in anticipating illness transmission in Portugal, even half a month ahead, is supported by the reported results. We contend that a stochastic strategy is required to account for imperfections in daily revealed assessments. Encasing any potential global outbreak adjustments would result in an intricate framework that would be computationally prohibitive and subject to overfitting67. The framework’s random noise includes crossovers with insignificant rates, for instance, those from infections to death. Adding infection rates for revealed quarantine leads to an equivalent or slightly worse fitting effectiveness. The parameter setup procedure when using non-linear techniques should be handled with extreme caution. Dynamic parameter estimation improves the validity of our model. The SEIQR model is widely used to characterize epidemics and includes the most commonly seen states. More recently, Ahsan et al.68 collected the images of MPV, using web mining techniques. Later on, they also evaluated a transfer learning approach with the SEIQR model considering two techniques69. The first technique considered the classification of images into two disease classes: MPV and Chickenpox, whereas the second technique augmented the images. They reported an accuracy of (97%) while classifying the MPV without data augmentation, whereas the accuracy was decreased to 78% with augmentation.

Table 5 shows the detailed results obtained by various NNs models for a specific classification task. The models were compared based on their accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, \(F_{1}\) score, training time, and size of model weight file.

Table 6 provides a comparative analysis of the relevant studies of MPV detection using ANN methods. The table includes the authors’ names and publication year, the purpose of the study, the proposed methodology, key parameters, and the models used in each study. The scores achieved by each study are also presented and discussed in detail in the subsequent sections of the paper using area under the curve (AUC) that represents the behavior of the models under various conditions. AUC can be calculated using following formulas \(AUC=\frac{\sum r_{i}(x_{p})-x_{p}(x_{p}+1)/2}{x_{p}+x_{n}},\) where \(x_{p}\) and \(x_{n}\) represent positive and negative samples of data, respectively, and \(r_{i}\) represents the rating of the ith positive sample. The studies included in the table are carefully selected to provide a comprehensive overview of the state-of-the-art approaches for detecting MPV. The comparison highlights the strengths and limitations of each study, and provides insights into the effectiveness of different methods and models used for MPV detection. The table serves as a useful reference for researchers and practitioners interested in this area, as it provides a clear understanding of the existing approaches and the gaps in knowledge that need to be addressed.

The study results indicate that the proposed scheme model’s performance has an accuracy of 97%, while the ResNet-18 model has an accuracy of 96.49%. The precision, recall, \(F_{1}\) score, and AUC score of the ResNet-18 are also significantly higher than the ResNet-50 model. The findings demonstrate that incorporating the Adam algorithm into the NN model has substantially improved its performance in terms of all evaluation metrics. The accuracy, precision, recall, \(F_{1}\) score, and AUC score have all increased when utilizing the LMBNN-MPV model compared to the non-optimized model. Specifically, the AUC score has improved, indicating a significant improvement in the model’s ability to distinguish among various techniques presented in table 5. The enhancement in other metrics such as recall, precision, and \(F_{1}\) score suggests that the Adam has resulted in better performance in accurately identifying and classifying positive instances. Overall, the findings demonstrate that LMBNN can be a valuable approach to improving the performance of NN models for MPV classification tasks.

As a consequence, we tested our model against a cutting-edge model that approaches our methods as accurately as feasible. The SEIQR model in terms of Poisson noise and LMBNN, as shown in Tables 2 and 3, has higher MSE values for infected and recovered cases than the suggested deterministic SEIQR model (1). The simulations in the outcomes section provide insight into the impact of MPV alternatives, including factors like rodent susceptibility and quarantine rates. Sections 4 and 5’s simulation outcomes for recovered rates justify the efficacy and advantages of MPV versus its negative consequences. A modest rise in immunization rates can significantly improve MPV control, with apparent impacts during the two population waves of the study time frame. This result aligns with other papers highlighting the significance of immunization campaigns in reducing morbidity and mortality rates66.

The MPV model (3) provides crucial insights into the outbreak’s propagation. The current research examines the mathematical features and prediction efficacy of the Poisson random measure stochastic epidemiology technique and LMBNNs approach. Derived formula for \(\mathbb {R}_{0\hbar }^{s}\) yields a more accurate representation of contagion propagation and allows us to arrive at crucial inferences regarding its progression. During 100 days, the reproduction rate fluctuates between 0.729 (1st quartile) and 1.939 (3rd quartile). Reproduction rates decline during quarantine but increase after restrictions are lifted.

In a nutshell, the methods given here can be used for several epidemics, including ebola, influenza, and yellow fever, as the postulated phases and transformations correspond to several of them. This technique is useful when real-time measurements and system behavior are insufficient to effectively depict the propagation of an outbreak owing to uncertainty. It eliminates noise that affects the emergence of states and measurements.

Discussion

The proposed approach of employing LMBNNs for classifying MPV shows significant potential; however, several challenges must be addressed:

-

(i) Limited data availability: Access to large, diverse datasets of MPV is scarce, which can hinder the model’s performance.

-

(ii) Data quality issues: Variations in image quality among available datasets may impact the accuracy of the LMBNN model.

-

(iii) Dataset bias: If the dataset used for training is not representative of the broader population, the model may produce biased results.

-

(iv) Overfitting risk: The LMBNN model might overlearn the training data, leading to poor generalization when applied to new, unseen cases.

-

(v) Lack of interpretability: LMBNNs are often perceived as “black boxes,” making it difficult to understand the reasoning behind their predictions.

-

(vi) Challenges in transfer learning: The effectiveness of transfer learning depends on the similarity between the pretraining dataset and the target dataset, which may vary.

-

(vii) Complex optimization process: Selecting the best hyperparameters and optimization strategies requires extensive computation and time.

-

(viii) Error analysis difficulties: Identifying and analyzing model errors can be challenging, making it harder to pinpoint areas for improvement.

-

(ix) Integration with healthcare systems: Incorporating this approach into existing healthcare workflows may necessitate significant changes and financial investment.

-

(x) High implementation costs: The expense of necessary technology and infrastructure could be a barrier in some healthcare settings.

-

(xi) Variability in real-world performance: The model’s real-world performance may differ due to patient diversity, environmental factors, and other unpredictable conditions.

-

(xii) Influence of confounding factors: Factors such as pre-existing medical conditions or medications can alter lesion appearance, affecting model accuracy.

-

(xiii) Limited generalizability: The approach may not be broadly applicable to other skin diseases or medical conditions requiring visual diagnosis.

While LMBNNs-based classification of MPV holds promise, addressing these challenges is essential for improving its reliability and clinical applicability.

The LMBNN-based approach utilized in the MPV study has the potential to be adapted for other types of data, including clinical records and imaging data, to enhance disease diagnosis and surveillance. For instance, it could be employed to analyze patterns in lung function tests or blood biomarkers to aid in diagnosing and predicting the progression of lung diseases such as pulmonary fibrosis, as highlighted in studies on lung disease screening. Likewise, applying this approach to clinical and imaging data from chest X-rays could improve the accuracy of machine learning-based COVID-19 diagnosis, as explored in research on ANN-driven diagnostic frameworks. However, further investigation is required to assess the feasibility and effectiveness of these applications.

Future direction

The potential for leveraging LMBNNs in classifying MPV is significant, with several promising areas for future research:

-

(i) Enhanced data collection and annotation: The study utilized a small clinical dataset with limited annotations. Future research should focus on curating larger, well-annotated datasets to enhance model accuracy and robustness.

-

(ii) Transfer learning: Leveraging pre-trained models can improve classification accuracy with minimal training data. Future studies can explore advanced transfer learning techniques to optimize model performance.

-

(iii) Multi-class classification: Expanding beyond binary classification (positive or negative for MPV) to multi-class classification could enable differentiation between various skin conditions, enhancing diagnostic utility.

-

(iv) Integration with clinical decision-making: ANN models can significantly aid healthcare professionals in diagnosing and treating skin conditions. Future work can focus on integrating MPV classification models into clinical decision-support systems.

-

(v) Application to other skin diseases: LMBNN-based models could be adapted for classifying other dermatological conditions, such as chickenpox, herpes, and shingles, broadening their clinical relevance.

-

(vii) Integration with telemedicine: LMBNN-powered classification models can be embedded into telemedicine platforms to improve healthcare access, particularly in underserved regions with limited dermatology expertise.

-

(viii) Explainability and interpretability: LMBNN models often function as black boxes, making their decision-making processes difficult to interpret. Future research can prioritize developing explainable ANN models to provide insights into model predictions and enhance trust among medical professionals.

Conclusion

MPV is a viral disease characterized by distinctive skin lesions and rashes, often making accurate diagnosis challenging through mere visual inspection. Given the limitations of traditional diagnostic approaches, this study explores the potential of ANN for the automated classification of MPV. The proposed LMBNNs-based approach was rigorously evaluated using key performance metrics, including accuracy, precision, and Poisson random measure. The model achieved an impressive 97% accuracy, outperforming existing classification methods. To further enhance performance, the LMBNN model was optimized using the Adams-Bashforth algorithm, which significantly improved all evaluation metrics compared to the non-optimized model. This demonstrates the effectiveness of the Adams-Bashforth algorithm in refining LMBNN performance for skin lesion classification tasks.

The findings suggest that machine learning techniques, particularly when optimized with adaptive moment estimation, can greatly improve the accuracy and reliability of MPV diagnosis. This approach is especially beneficial for resource-constrained settings where access to specialized dermatological expertise may be limited. By integrating ANN-driven solutions into public health frameworks, early detection and surveillance of MPV cases can be strengthened, leading to better outbreak management and disease control.

In conclusion, this study underscores the transformative role of LMBNNs and optimization techniques in medical image analysis and detecting virus, showcasing their potential to revolutionize disease diagnosis and contribute to more effective public health interventions. As future work, it would be interesting to consider a hybrid epidemiological particle filter, as particle filtering constitutes another approach that deals with the uncertainty that accompanies the equations of states and observations of a phenomenon such as a pandemic. To better mimic epidemic outbreaks, consider using a Tobit-Kalman filter75 or a Kalman filter with non-negative restrictions76. Employing probabilistic techniques like discrete or continuous time Markov chains to study the development of diseases is also an increasingly prevalent subject. Applying Markov chain processes predicated on the SEIQR model, we may investigate stochastic features such as vulnerable individuals’ quarantine time, infectious wave time frame, and number of deaths. These efforts could be the focus of future assessment.

Data availability

The data sets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Gessain, A., Nakoune, E. & Yazdanpanah, Y. Monkeypox. New England J. Med. 387(19), 1783–1793 (2022).

Leggiadro, R. J. Emergence of Monkeypox-West and Central Africa, 1970–2017. The Pediatric. Infect. Disease J. 37(7), 721 (2018).

Formenty, P. et al. Human monkeypox outbreak caused by novel virus belonging to Congo Basin clade, Sudan, 2005. Emerg. Infect. Disease. 16(10), 1539 (2010).

Parker, S., Nuara, A., Buller, R. M. L. & Schultz, D. A. Human monkeypox: an emerging zoonotic disease. Future Med. 2(1), 17–34 (2007).

Thornhill, J. P. et al. Human monkeypox virus infection in women and non-binary individuals during the 2022 outbreaks: a global case series. The Lancet. 400(10367), 1953–1965 (2022).

Papageorgiou, V. E., Kolias, P. A novel epidemiologically informed particle filter for assessing epidemic phenomena. Application to the monkeypox outbreak of 2022, Inv. Probl. 40(3), (2024).

Sebbagh, A. & Kechida, S. EKF-SIRD model algorithm for predicting the coronavirus (COVID-19) spreading dynamics. Sci Rep. 12, 13415. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-16496-6 (2022).

Papageorgiou, V. E., Tsaklidis, G. An improved epidemiological-unscented Kalman filter (hybrid SEIHCRDV-UKF) model for the prediction of COVID-19. Application on real-time data. Chaos Solit. Fract. 166, 112914 (2023).

Papageorgiou, V. E. & Tsaklidis, G. A stochastic particle extended SEIRS model withrepeated vaccination: Application to real data of COVID-19 in Italy. Math. Meth. Appl. Sci. 47, 6504–6538 (2024).

Christodoulidou, P., Papageorgiou, V. E., Tsaklidis, G. Enhancing infectious disease modelling through a Kalman-based (HCRD-R) epidemiological approach. Application to COVID-19 data during the vaccination period, Commun. Math. Biol. Neurosci., 2024, 98 (2024).

Artalejo, J. R., Economou, A. & Lopez-Herrero, M. J. The stochastic SEIR model before extinction: Computational approaches. Appl. Math. Comput. 265, 1026–43 (2015).

Papageorgiou, V. E. & Tsaklidis, G. A stochastic SIRD model with imperfect immunity for the evaluation of epidemics. Appl. Math. Model. 124, 768–90 (2023).

Papageorgiou, V. E. Novel stochastic descriptors of a Markovian SIRD model for the assessment of the severity behind epidemic outbreaks. J. Franklin. Inst. Journal of the Franklin Institute 361(12), 107022 (2024).

Papageorgiou, V. E. & Vasiliadis, G. Transient analysis of a SIQS model with state capacities using a non-homogeneous Markov system. J. Franklin. Inst. 362(1), 107347 (2025).

Pérez, M. G., Lopez-Garcia, M., Lopez-Herrero, M. A stochastic SVIR model with imperfect vaccine and external source of infection. In: Lecture Notes in Computer Science, 97-209 (2021).

Gamboa, M., Lopez-Herrero, M. J. The effect of setting a warning vaccination level on a stochastic SIVS model with imperfect vaccine. Mathematics. 8(7), 11362020.

Lum, F. M. et al. Monkeypox: disease epidemiology, host immunity and clinical interventions. Nat Rev Immunol 22, 597–613. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41577-022-00775-4 (2022).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC and others). Multistate outbreak of monkeypox-Illinois, Indiana, and Wisconsin, 2003. MMWR. Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 52(23), 537-540 (2003).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC and others). Update: multistate outbreak of monkeypox- Illinois, Indiana, Kansas, Missouri, Ohio, and Wisconsin, 2003. MMWR. Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 52(24), 561-564 (2003).

Moore, M. J., Rathish, B. & Zahra, F. Monkeypox (StatPearls Publishing, StatPearls, 2022).

Petersen, B. W. et al. Vaccinating against monkeypox in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Antiviral research 162, 171–177 (2019).

Vaughan, A. et al. Two cases of monkeypox imported to the United Kingdom. Eurosurveillance 23(38), 1800509 (2018).

Vaughan, A., Aarons, E., Astbury, J., Brooks, T., Chand, M., Flegg, P., ... & Dunning, J. Human-to-human transmission of monkeypox virus, United Kingdom, October 2018. Emerg Infect. Diseases, 26(4), 782 (2020).

Alakunle, E., Moens, U., Nchinda, G. & Okeke, M. I. Monkeypox virus in Nigeria: infection biology, epidemiology, and evolution. Viruses 12(11), 1257 (2020).

Kantele, A., Chickering, K., Vapalahti, O. & Rimoin, A. W. Emerging diseases-the monkeypox epidemic in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Clinical Microbiology. Infect 22(8), 658–659 (2016).

Shi, R. & Zhang, Y. Dynamic analysis and optimal control of a fractional order HIV/HTLV co-infection model with HIV-specific antibody immune response. AIMS Math 9(4), 9455–9493. https://doi.org/10.3934/math.2024462 (2024).

Atangana, A. & Rashid, S. Analysis of a deterministic-stochastic oncolytic M1 model involving immune response via crossover behaviour: ergodic stationary distribution and extinction. AIMS Math 8(2), 3236–3268. https://doi.org/10.3934/math.2023167 (2023).

Shah, K., Sinan, M., Abdeljawad, T., El-Shorbagy, M. A., Abdalla, B., Abualrub, M. S. A Detailed study of a fractal-fractional transmission dynamical model of viral infectious disease with vaccination, Complexity, 2022, Article ID 7236824 (2022).

Ma, Y. & Yu, X. Stochastic analysis of survival and sensitivity in a competition model influenced by toxins under a fluctuating environment. AIMS Math 9(4), 8230–8249. https://doi.org/10.3934/math.2024400 (2024).

Al-Qureshi, M., Rashid, S., Jarad, F. & Alharthi, M. S. Dynamical behavior of a stochastic highly pathogenic avian influenza A (HPAI) epidemic model via piecewise fractional differential technique. AIMS Math 8(1), 1737–1756. https://doi.org/10.3934/math.2023089 (2023).

El Fatini, M. & Sekkak, I. Lévy noise impact on a stochastic delayed epidemic model with Crowly-Martin incidence and crowding effect. Physica A. 541, 123315 (2020).

Dong, Y. & Lin, T. Dynamics of a stochastic rumor propagation model incorporating media coverage and driven by Lévy noise. Chin. Phys. B 30, 080201 (2021).

Guarcello, C., Valenti, D., Carollo, A. & Spagnolo, B. Effects of Lévy noise on the dynamics of sine-Gordon solitons in long Josephson junctions. J. Stat. Mech. 2016, 054012 (2016).

Caraballo, T., Fatini, M. E., Khalifi, M. E. & Rathinasamy, A. Analysis of a stochastic coronavirus (COVID-19) Lévy jump model with protective measures. Stoch. Anal. Appl. 41, 45–59 (2023).

Zhu, Y., Wang, L. & Qiu, Z. Dynamics of a stochastic cholera epidemic model with Lévy process. Physica A 595, 127069 (2022).

Silitonga, P., Bustamam, A., Muradi, H., Mangunwardoyo, W. & Dewi, B. E. Comparison of Dengue Predictive Models Developed Using Artificial Neural Network and Discriminant Analysis with Small Dataset. Appl Sci. 11(2), 943 (2021).

Laureano-Rosario, A. E. et al. Application of artificial neural networks for dengue fever outbreak predictions in the Northwest Coast of Yucatan, Mexico and San Juan. Puerto Rico. Trop. Med. Infect. Disease. 3(1), 5 (2018).

Kenneth, L. A method for the solution of certain non-linear problems in least squares. Quart. Appl. Math. 2(2), 164–168 (1944).

European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Monkeypox multi-country outbreak - second update, 18 October. https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/monkeypox-multi-country-outbreak-second-update (2022).

World Health Organization. Mpox (monkeypox). https://www.who. int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/monkeypox (2019) Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Update: multistate outbreak of monkeypox - Illinois, Indiana, Kansas, Missouri, Ohio, and Wisconsin, 2003. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly Rep. 52, 561-564 (2003).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Update. multistate outbreak of monkeypox - Illinois, Indiana, Kansas, Missouri, Ohio, and Wisconsin, 2003. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly Rep. 52, 561–564 (2003).

Manohar, B., Das, R. & Lakshmi, M. A hybridized LSTM-ANN-RSA based deep learning models for prediction of COVID-19 cases in Eastern European countries. Expert. Sys. Appl. 256, 124977 (2024).

Lakshmi, M., Das, R. & Manohar, B. A new COVID-19 classification approach based on Bayesian optimization SVM kernel using chest X-ray datasets. Evolving Sys. 15, 1521–1540. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12530-024-09575-8 (2024).

Manohar, B. & Das, R. Comparison of hybrid artificial neural networks with GA, PSO, and RSA in predicting COVID-19 cases: a case study of India. IGI Global. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-6684-4466-5.ch011 (2023).

Chandra, A., Kulshreshtha, A. & Kaliraman, N. Artificial neural network-based stock price prediction using Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm. Inter. J. Comp. Sci. Inform. Tech. Res. 8(2), 1–4 (2020).

Roser, M., Ortiz-Ospina, E., Ritchie, H. Our World in Data. University of Oxford. 2013. Available from: https://ourworldindata.org/

Manohar, B. & Das, R. Artificial neural networks for the prediction of monkeypox outbreak. Trop. Med. Infect Disease. 7(12), 424. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed7120424 (2022) (PMID: 36548679).

Borges, V. et al. Viral genetic clustering and transmission dynamics of the 2022 mpox outbreak in Portugal. Nature Medicine 29, 2509–2517 (2023).

Wang, L., Wang, Z., Qu, H. & Liu, S. Optimal forecast combination based on neural networks for time series forecasting. Appl. Soft. Comp. 66, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asoc.2018.02.004 (2018).

Tamang, S. K., Singh, P. D. & Datta, B. Forecasting of Covid-19 cases based on prediction using artificial neural network curve fitting technique. Global J. Envir. Sci. Mana. 6, 53–64 (2020).

Saritas, I. Prediction of breast cancer using artificial neural networks. J. Med. Sys. 36, 2901–2907. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10916-011-9768-0 (2012) (PMID: 21837454).

Guarcello, C., Valenti, D., Carollo, A. & Spagnolo, B. Effects of Lévy noise on the dynamics of sine-Gordon solitons in long Josephson junctions. J. Stat. Mech: Theory. Exper 5, 054012 (2016).

Berrhazi, B. E., El Fatini, M., Caraballo Garrido, T. & Pettersson, R. A stochastic SIRI epidemic model with Lévy noise. Dis. Cont. Dyn. Syss-Ser B 23(9), 3645–3661 (2018).

Gikhman, I. I., Skorokhod, A. V., Gikhman, I. I. & Skorokhod, A. V. Stochastic Differential Equations (Springer, Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007).

El Fatini, M. & Sekkak, I. Lévy noise impact on a stochastic delayed epidemic model with Crowly-Martin incidence and crowding effect. Physica A. 541, 123315 (2020).

Din, A. & Li, Y. Lévy noise impact on a stochastic hepatitis B epidemic model under real statistical data and its fractal-fractional Atangana-Baleanu order model. Phy Scr 96(12), 124008 (2021).

Guarcello, C., Valenti, D., Carollo, A. & Spagnolo, B. Effects of Lévy noise on the dynamics of sine-Gordon solitons in long Josephson junctions. J. Stat. Mech: Theory Exper 2016(5), 054012 (2016).

Zhang, X. B., Wang, X. D. & Huo, H. F. Extinction and stationary distribution of a stochastic SIRS epidemic model with standard incidence rate and partial immunity. Physica A: Stat. Mech. Appl 531, 121548 (2019).

Song, Y., Liu, P. & Din, A. A novel stochastic model for human Norovirus dynamics: vaccination impact with Lévy noise. Fract. Fract 8(6), 349 (2024).

Khan, T., Khan, A., & Zaman, G. The extinction and persistence of the stochastic hepatitis B epidemic model. Chaos, Solit. Fract, 108, 123-128 (2018).

Zhu, Y., Wang, L. & Qiu, Z. Dynamics of a stochastic cholera epidemic model with Lévy process. Physica A: Stat. Mech. Appl 595, 127069 (2022).

Ain, Q. T., Din, A., Qiang, X. & Kou, Z. Dynamics for a Nonlinear Stochastic Cholera Epidemic Model under Lévy Noise. Fract. Fract 8(5), 293 (2024).

Mao, X., Wei, F. & Wiriyakraikul, T. Positivity preserving truncated Euler-Maruyama method for stochastic Lotka-Volterra competition model. J. Comput. Appl. Math 394, 113566 (2021).

Thornhill, J. P. et al. Monkeypox virus infection in humans across 16 countries - April-June 2022. N. Engl. J. Med. 387, 679–691 (2022).

World Bank, Incidence of tuberculosis (per 100,000 people). https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.TBS.INCD.

Peter, O. J. et al. Transmission dynamics of Monkeypox virus: a mathematical modelling approach. Model. Earth. Sys. Env. 8, 3423–3434 (2022).

Sitaula, C. & Shahi, T. B. Monkeypox virus detection using pre-trained deep learning-based approaches. J. Med. Syst. 46, 78. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10916-022-01868-2 (2022).