Abstract

Despite growing interest in adopting water-conserving strategies such as deficit irrigation (DI) and biochar amendment in arid and semi-arid regions, there are remarkably few studies conducted on the integration of these two strategies in water limited West Texas region. The aim of this study was to assess the interactive effects of DI and biochar amendment on saturated hydraulic conductivity of soil and the growth, physiology and yield of cucumber (Cucumis sativus) in West Texas. A split-plot design was used to randomize four irrigation treatments (with two levels before and after mid-season) as the main plot [I1: 100% crop evapotranspiration (ETc)-100% ETc, I2: 80% ETc-60% ETc, I3: 60% ETc-80% ETc, I4: 40% ETc-40% ETc] and three biochar rates as subplot [0 t/ha, 15 t/ha, and 20 t/ha] with four replications. Irrigation level I4 negatively impacted chlorophyll content, stomatal conductance, transpiration, photosynthesis, and intrinsic water use efficiency (iWUE) when the weather was hot and dry in 2022 compared to other treatments. Leaf area index (LAI) under I4 declined significantly by 52% and the final dry biomass by 47% compared to I1 across two years, although I3 reduced biomass by 17% only in 2022. As compared to I1, the yield penalties due to water stress in I2, I3, and I4 were 14, 16, and 34%, respectively, across two years. Although biochar rates 15 t/ha and 20 t/ha significantly increased the saturated hydraulic conductivity of soil by 1.6 and 2.2 folds in 2022 compared to the unamended control but biochar’s impact on cucumber growth, physiology, and yield was minimum during both years. Hence, our findings suggest that I2 can be adopted as an alternative to full irrigation which requires 25% less water and has 14% narrow yield gap. Biochar studies are needed to assess whether added biochar has an apparent long-term effect on improving cucumber yield.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Ogallala aquifer supplies water to eight states1in the U.S. to meet water needs for agriculture and public use2. The Texas High Plains (THP) is a semi-arid region that satisfies 90% of its irrigation needs from the Ogallala aquifer3. However, the water withdrawal rate of the aquifer exceeds its recharge rate, creating a depletion of the water table in the region, which makes irrigated agriculture difficult to sustain2. Therefore, there is a need to develop water-conserving management strategies to sustain crop production and the longevity of the Ogallala aquifer in the water-scarce THP4.

Deficit irrigation (DI) is a widely practiced strategy in water-limited agriculture regions to manage and conserve water resources. Under DI practices, the crop is supplied with less water than its ET water demand that can enhance water use efficiency (WUE) calculated as yield per amount of water used5. Deficit irrigation essentially helps to save a considerable amount of water in irrigated agriculture especially where water management and conservation practices are highly needed6. Deficit irrigation is highly recommended in semi-arid and arid regions where the main goal is to enhance yield per unit of water (i.e., water productivity) rather than yield per unit of area or land (i.e., land productivity)7. The response of DI depends on the crop, crop stages, as well as varieties8. Kirda6reported that DI could stress the crop by limiting the water supply during a certain growth period or the whole crop season. The crop requires different amounts of water at various growth stages, i.e., vegetative and reproductive stages9, and hence, the growth stage-based DI management has been shown to be successful in many crops10,11. When knowledge of irrigation scheduling is limited, the inappropriate amount of water supplied to the crop may not be optimally utilized by the crops, resulting in low water productivity. However, before applying any irrigation strategies, it is imperative to understand the physiological response of crops to water stress at different growth periods12.

Water stress leads to many biochemical and physiological changes in plants at different growth stages, ultimately bringing morphological changes13. Different crops respond differently to water stress based on their water stress tolerance ability. Generally, when the plants are stressed, the stomata tend to close, which limits the gaseous exchange, decreases CO2assimilation, and reduces transpiration. This decreases leaf-level photosynthesis, and ultimately, overall growth is reduced14. These parameters may alter depending on the growth stage of the crop under water stress. Prolonged water stress during the critical growth period of the crop can be detrimental; hence, recognizing that sensitive growth stage is imperative while adopting DI. Any changes in physiological parameters during the critical growth period can be a good indicator for estimating the productivity of crops under water-limited conditions. This is because water stress in this stage alters many morphological and physiological parameters that significantly determine yield15.

Cucumber (Cucumis sativus) is a shallow-rooted moderate water stress tolerant summer crop and has its maximum rooting at 20–30 cm depth with negligible root fiber extension below 60 cm16,17. It is grown on ~ 2500 ha in Texas, where west Texas alone shares 50% of the cultivated area18. According to the USDA Vegetable Summary report of 2022, Texas alone shares more than 9 million US dollars in value for the national economy from the fresh cucumber market19. However, the production of cucumber has been impacted by extreme climatic conditions and water scarcity in the West Texas region4. It has been reported that significant yield reduction occurs with prolonged water deficiency during cucumber production20. However, Mao, et al.17found that WUE was higher with greater irrigation water amount supplied from crop establishment to first fruit ripening but reduced afterward until the end of the fruit harvest. It has been described that cucumbers do not need continuous high irrigation throughout their growth stage. Rahil and Qanadillo21 reported that 70% ET replacement produced a 2.2 t/ha higher yield than 100% ET replacement irrigation in cucumber. In a greenhouse experiment with Japanese cucumber, Oliveira, et al.22found that stressing the crop at the reproductive stage reduced yield significantly compared to the vegetative stage. During flowering and fruiting, more energy exerted by a plant was directed to absorb water from the soil, which caused the flower abortion and small fruit sizes. A greenhouse study was conducted at 40, 60, 80, and 100% ET replacement irrigation levels at different growth stages of cucumber, i.e., initial, developmental, middle, and late, and found that initial and late stages were the most sensitive, the developmental stage being the highest tolerant stage for DI in terms of yield23. A cucumber experiment conducted by Parkash, et al.4 showed that cucumber can have a similar yield at 80% ET compared to 100% ETc. This finding has provided more room to develop a growth stage-based ET requirement rather than a seasonal ET strategy to save more water in this region.

Other water-conserving farming strategies, such as soil amendments, could be integrated with DI for a water-limited or water-stressed production system24. Soil amendments are farm inputs applied to soil to improve soil properties, which could later help crop production. Biochar, a promising soil amendment, is a highly porous stable carbon compound obtained from burning plant residues in a limited oxygen environment at high temperatures25. As biochar has a greater capacity to retain water in the soil, its potential for adoption as a soil amendment is increasing in water-scarce regions26,27. It has been reported that in 90% of studies, the application of biochar has increased water holding capacity in different soil types28. Although the application of biochar has resulted in an enhanced favorable response in soil, there is no consensus as to the upper or maximum limit of biochar application rates or amounts, especially depending on the variability of soil and crop type29. Moreover, the source of biochar (feedstock), pH, and nutrient content of biochar also determine the application rates of biochar30. Liu, et al.31mentioned that an application rate below 30 t/ha can have positive effects on crop productivity but largely depends upon the crop type. Lehmann, Gaunt and Rondon32reported that 55 t/ha of biochar is the upper limit for any crop. However, Filiberto and Gaunt29recommended 25 t/ha as the upper limit for crop production. Since many studies investigating different application rates of biochar as soil amendments have reported varied and contrasting results on the upper or maximum limits of biochar application rates33,34, it is difficult to generalize recommendations for various crops based on individual studies. Hence, there is a need for a site-specific recommendation rate of biochar for growers that could help increase crop productivity.

Among different soil hydraulic parameters, saturated hydraulic conductivity (Ksat) is of immense importance in determining soil quality associated with water flow in the soil35. In a review, Blanco-Canqui28highlighted that biochar reduced Ksat in 12 coarse-textured soil studies by 7–2270% but increased Ksat in 8 fine-textured soil studies by 25–328% because of the high coefficient of variation in soil properties. A greenhouse study in sandy and sandy loam soils with rice husk biochar at a rate of 0, 0.1, 0.5 and 1% (w/w) showed an increase in Ksat value by 54–78% in sandy soil and 82–148% in sandy loam soil with > 0.5% (corresponding to 10.5 t/ha) biochar rates due to enhanced macro-aggregation36. Another study by Toková, et al.37 revealed that biochar application at 20 t/ha had the greatest improvement in soil Ksat by 464 and 350% under control (i.e., without biochar application or non-amended soil) and 108 kg/ha fertilizer application, respectively, in silty loam soil. These reports show that biochar response can vary depending on the soil texture and application rate. Therefore, while biochar is broadly purported to provide agricultural benefits via biochar-induced changes in soil hydraulic properties in many studies, a site-specific biochar application recommendation is still needed in the West Texas region, especially after examining its impact on soil hydraulic properties, such as the Ksat of soil, under semi-arid conditions of West Texas.

Many pieces of literature repeatedly examined the effect of either biochar amendment or DI strategy individually on different crops. However, Singh, et al.27 emphasized that field studies integrating these two management practices are still scarce, especially in semi-arid regions. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first instance that has implemented the combination of these two well-recognized water-saving strategies to grow cucumbers under semi-arid conditions in West Texas. This novel research will help to explore the feasibility of irrigation and soil amendment in sustainable production of cucumber which is rarely investigated area in the region. Our hypothesis for this study is that the integration of DI and biochar would significantly enhance cucumber productivity. Therefore, this study aimed to (i) investigate the effect of biochar rates on the Ksat of soil, and (ii) evaluate the integrated effects of DI and biochar rates on growth, physiology, and yield of cucumber in West Texas.

Materials and methods

Study location

A two-year field study was conducted from April through August in 2021 and 2022 at Quaker Research Farm of Texas Tech University, Lubbock, TX (33° 36′ 18″ N, −101° 54′ 26″W, and 992 m above sea level). The study site was a semi-arid region with an average annual evapotranspiration of 1,501 mm and an average annual rainfall of only 469 mm38. The study location had an average annual low and high temperatures of 8.3℃ and 23.3℃, respectively. The soil type was deep, well-drained, friable, dark grayish brown, and neutral to moderately alkaline with a slope gradient of 0–1%39. The soil texture (0–10 cm), measured on collected soil samples at the beginning of the experiment in 2021 using the hydrometer method40,41, was sandy clay loam with a particle size distribution of 55% sand, 11% silt, and 33% clay. The description of soil nutrient status is presented in Table 1.

Experimental design and cultivation practices

The experimental units were randomized four times in a blocked split-plot design with four growth-stage based irrigation levels: I1 [100% crop evapotranspiration (100% ETc) replacement from crop establishment to mid-season (50–55 days after planting) CMS-100% ETc replacement from mid-season to maturity (MSM)], I2 (80% ETc CMS-60% ETc MSM), I3 (60% ETc CMS-80% ETc MSM), I4 (40% ETc CMS-40% ETc MSM) as main plot factor and three biochar rates (0 t/ha,15 t/ha, and 20 t/ha) as subplot factor. Each plot was 4 m wide and 6 m long with raised beds (i.e., ridges) of approximately 50 cm wide and 15 cm high. The irrigation was applied via the sub-surface drip irrigation system. The drip tapes were buried in the soil at a depth of approximately 30–35 cm from the top of the ridge. The experimental field consisted of four irrigation zones, each equipped with an independent flow control system or regulator and a flowmeter, to apply irrigation treatments (i.e., I1, I2, I3, and I4). Within an irrigation zone, each plot was separated by 1.5 m wide alleys.

At the start of the experiment each year (January-February of 2021 and 2022), the experiment field was plowed with a tractor-mounted disc plow during winter to break large clods and obtain fine tilth. Pre-plant fertilizer URAN 32 (NPK 32-0-0, Nutrien Ag Solution, Loveland, CO) was applied through fertigation once before planting based on a soil fertility test at the rate of 80 kg N/ha. Hardwood biochar prepared from Oak tree (Wakefield™ BioChar, Valdosta, GA) was used for the study, and the physical and chemical properties of this hardwood biochar can be found in Singh, et al.13. The biochar was spread evenly on the soil surface in treatment plots and incorporated to a depth of approximately 15–20 cm, along with the preparation of raised beds using a tractor-mounted rotary tiller on March 18, 2021. The cucumber cultivar Bristol (Rupp Seed Inc., Wauseon, OH) was selected for this study due to its specific adaptation to the semi-arid environments of West Texas. The planting was done on June 10, 2021, and June 6, 2022, by a tractor-mounted four-row planter with row-to-row spacing of 1 m at the rate of 45,000 seeds/ha.

Cucumber, grown under each of the four DI treatments (I1, I2, I3 and I4), was irrigated based on the ETc calculated by multiplying reference evapotranspiration (ETo) by crop coefficient (Kc). The daily ETo was calculated from weather data using the Penman-Monteith method42. The daily weather data was collected from a weather station (Davis Wireless Vantage Pro2, Hayward, CA) installed near the study location. The growth stage-specific crop coefficient of cucumber was Kc initial = 0.45 (0–20 Days After Planting; DAP), Kc crop dev. = 0.70 (21–50 DAP), Kc mid = 0.90 (51–90 DAP), Kc late= 0.75 (91–105 DAP)4,43. Each irrigation zone had a separate irrigation valve which emitted approximately 1 inch of water in 24 h. Based on the water requirement, irrigation valves were opened for a certain amount of time to supply the required volume of water at every irrigation event. Irrigation was applied and adjusted based on the calculated ETc requirements and rainfall events from the previous week.

Measurements and data collection

Soil sampling for saturated hydraulic conductivity (Ksat)

To assess the effect of biochar on soil hydraulic property, soil core samples from 0 to 5 cm soil depth were collected in a stainless-steel soil core ring of 5 cm in height ×8 cm in diameter. The soil core ring was first vertically pressed into the soil by hand and then placed a block of wood on top and pushed further by steady hammering till the core sampler was driven down to the surface of the soil. Both ends of the soil core ring were closed by plastic end caps to help prevent breakage of the soil core and preserve soil sample integrity. Soil core samples were collected from eight replicated plots under each biochar treatment. After leveling the soil at each end of the soil core ring, one end of the ring was placed over a gasket with the porous plate, and it was saturated in deionized water for 24 h. The core was placed over the measuring dome with a crown and screw cap over the core in the Ksat benchtop instrument (Meter Group, Inc., Pullman, WA, USA). Using the Falling Head method, water from the burette was allowed to pass through the saturated soil in the sample core until the steady-state flow (cm/day) was not achieved and the pressure head difference reached a stop criterion44.

The Ksat works based on the Darcys’ equation under the principle of hydraulic gradient which is explained by the following Eqs. 1 and 2 adapted from the44.

Where, L = length of the sample, V = volume of water passing through the core soil sample, H = height of the water column, A = cross-sectional area of the core soil sample, T = time to travel water through the soil sample, a = burette cross-sectional area, L = length of soil sample, Ho and Ht = initial and final hydraulic head difference t = time taken to drop pressure head from Ho to Ht in burette.

Plant physiological parameters

To assess the effect of DI and biochar rates on the physiological responses of cucumber, a portable photosynthesis system (Model LI-COR-6800, LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE) was used to measure net photosynthesis (Pn), stomatal conductance (gs), transpiration (E) and instantaneous water use efficiency (iWUE). All these leaf-level measurements were conducted on the two youngest, fully expanded, sunlit leaves for two random plants in each treatment plot. The photosynthesis system was set at a steady state at 1,500 µmol m–2 s–1 photosynthetic active radiation (PAR), 400 µmol mol–1 reference CO2 concentration, 700 µmol–1air flow rate, 65% of relative humidity while switching the temperature control off13. The measurements of plant physiological parameters were taken between 10:00 am and 2:00 pm local time when the leaves were fully active, and PAR was high at 33, 62, and 72 DAP in 2021, and 42, 71, and 92 DAP in 2022, respectively. The leaf chlorophyll content (µmol/m2) was also measured using the portable MC-100 chlorophyll concentration meter (Apogee Instrument, Logan, UT) on the same observation dates (i.e. 33, 62, and 72 DAP in 2021, and 42, 71, and 92 DAP in 2022) in both years.

Leaf area index, biomass, and yield

The LAI was measured in each treatment plot using the AccuPAR Ceptometer (LP-80, Decagon Device Inc., Pullman, WA) at local noon time when the sun was approximately perpendicular to the cucumber plants in rows. The measurements of LAI were made at 33, 62, and 72 DAP in 2021, and 42, 71, and 92 DAP in 2022, respectively. The plants (leaves and vines) were oven-dried at 70℃ for 72 h to achieve a constant weight. The plant dry biomass was then recorded using a weighing scale at 72 DAP and 92 DAP in 2021 and 2022, respectively. Matured fruits of marketable size were harvested once a week after 44 DAP in 2021 and 48 DAP in 2022 from an area of 6 m2 in each plot, and the total number of fruits (fruits/ha) and the total fruit yield (t/ha) were recorded. The average weight per individual fruit was calculated by dividing the total fruit weight by the total number of fruit weighed in each plot.

Statistical analysis

The collected data were analyzed using the analysis of variance (ANOVA) with a split-plot design in R-Studio version 3.5.245using the Agricolae package version 1.2–846. Data for each measurement date (i.e., DAP) and each year were analyzed separately. The treatment means were separated using the Fisher’s protected least significant difference (LSD) test at a 0.05 level of significance. There were no interactions between irrigation and biochar factors for the data; hence, only the main effects are presented and discussed. The graphs were prepared using SigmaPlot software version 14 (Systat Software, San Jose, CA).

Results and discussion

Weather conditions and irrigation

The average temperature and relative humidity (RH) were 26.3℃ and 58.8% in 2021 (Fig. 1), and 27.1℃ and 49.7% in 2022 (Fig. 2), respectively. The daily average solar radiation received was 22.4 MJ/m2 in 2021 and 23.1 MJ/m2in 2022. The total rainfall amounts during the study were 149.8 and 118.7 mm in 2021 and 2022, respectively. The data showed that the second year (2022) was comparatively hotter and drier than the first year (2021). In 2021, rainfall was mostly received in the early and mid-stage, while it was majorly concentrated during the later growth stage of the cucumber plants in 2022. Relative to 2021, the uneven rainfall distribution in 2022 exposed the cucumber plants to more stressed conditions during their early-mid growth stages. Similarly, plants started to decay at a later stage in 2022, and the high rainfall events caused leaves to die and fall, resulting in fewer harvest events (only six times) compared to 2021 harvests (seven times)47. The total reference evapotranspiration (ETo), which was used in calculating ETc, over the growing season was 702 mm in 2021, while it was 737 mm in 2022. This resulted in variations in the amount of irrigation applied in both years for different DI treatments for cucumber production4. In 2021, a total of 341 (I1), 249 (I2), 306 (I3), and 185 (I4) mm of irrigation amounts were applied. The total amounts of irrigation applied to different treatments in 2022 were higher, i.e., 452 (I1), 353 (I2), 374 (I3), and 283 (I4) mm, owing to the lower amount of rainfall and higher ETc requirement of the cucumber plant. The different DI treatments evaluated in this study resulted in irrigation water saving of 27% (I2), 10% (I3), and 46% (I4) in 2021, and 22% (I2), 17% (I3), and 37% (I4) in 2022, as compared to the control (I1).

Effect of biochar amendment on saturated hydraulic conductivity of the soil

There was no significant difference among biochar treatments for Ksat in 2021, but it significantly improved in biochar-amended treatments (15 and 20 t/ha) in 2022 (Fig. 3). The biochar treatments 15 t/ha and 20 t/ha increased Ksat by 1.6 and 2.2 folds, respectively, compared to 0 t/ha (i.e., the control) in 2022. The Ksat of the soil, which relates soil water flow rate to the hydraulic gradient, is a measure of the ease of water movement through the soil and considered one of the metrics of soil physical quality35,48. Zhou, et al.49reported that the porous compound biochar reduced the bulk density of soil, improved soil porosity, and ultimately increased the hydraulic property. The porous biochar that was added in our study might have contributed the porosity of the soil enhancing the pathway for water to flow in a soil. Blanco-Canqui28reviewed different studies that presented varying effects of biochar amendments on soil hydrological properties and reported that biochar influenced Ksat in coarse-textured soils to a greater degree than fine-textured soils. As mentioned in earlier, soils at the study site were characterized by 33.3% clay content and the added porous compound biochar most likely enriched the soil with the macro- and mesopores, thereby enhancing the hydraulic property of the soil by which it permits the movement of water through it (i.e., hydraulic conductivity). Our finding is consistent with a previous study, in which the wood biochar at 16 t/ha increased the Ksat by 176% compared to 0 t/ha (non-amended) in clay loam soil50. The effect of biochar in our study increased the Ksat by 61% and 121% in 15t/ha and 20 t/ha biochar in 2022, respectively in sandy clay loam soil. This difference in the enhancement due to biochar could be caused by different soil types. Another study by Lim, et al.51 also reported an increase in Ksat under 1% and 2% (w/w) biochar amendment in clay loam soil compared to coarse sandy soil, underscoring the effect of soil textures on biochar-induced changes in soil Ksat. Notably, while most of the previous studies are limited to laboratory or greenhouse or controlled conditions, the findings in this study further clarified our understanding of the changes in soil Ksat associated with biochar addition under semi-arid field conditions. The insignificant difference in soil Ksat among treatments in the first year could be explained by the fact biochar might take more time to reach its full potential since the soil samples for determining Ksat were collected after five months of biochar incorporation. There is still no consensus on exactly how long it takes for the added biochar to be integrated with the soil to bring the most benefits to it, and the literature provides contrasting results in different studies. Wang, et al.52 reported no significant alternation in Ksat in expansive clayey soils after one year of biochar application, whereas Jačka, et al.53 reported significant benefits due to biochar on Ksat within some hours of application in sandy soil loam. Ouyang, et al.54 mentioned that the addition of biochar significantly improved the macro aggregates and increased the saturated hydraulic conductivity of the soil once biochar settled in the soil. So, depending upon settling time and soil types, the effects of biochar on Ksat vary.

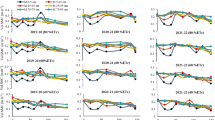

Responses on physiological parameters under integrated strategies of deficit irrigation and biochar soil amendment

Chlorophyll content

Studies have indicated that water stress can bring varying effects on leaf chlorophyll content because it can either increase55, decrease56, or have no effect57 for various crops. In our study, we found that moderate plant water stress induced by DI levels, i.e., especially I2 and I3 treatments, can occasionally increase the leaf chlorophyll content in cucumber compared to non-stressed (the control I1) and highly stressed (I4) plants in 2021 and 2022 (Fig. 4A and B). The chlorophyll content in DI treatments (I2, and I4) was found to be significantly higher compared to I1 at 33 DAP but remained unaffected for the rest of the growing period in 2021 (Fig. 4A). It could be due to the occurrence of frequent rainfall events during the 2021 growing season, which might have resulted in relatively lower water stress conditions and contributed to relatively similar leaf greenness. With a given rainfall event that could favor the optimal soil water status in the root zone, plant uptakes of nitrogen (N) and magnesium (Mg) available in the soil could contribute to leaf sizes and help optimize chlorophyll synthesis58. However, in 2022, the leaf chlorophyll content was found to be enhanced, especially in DI treatment I3, but reduced to the least in I4 when compared with I1 at 70 DAP. At 70 DAP and 90 DAP in 2022, the significant drop in chlorophyll content in I4 was likely associated with lower N uptake rates59,60 as there might be less availability of water to solubilize N and transport it to the plant. Our results agree with the findings of a previous study, in which the leaf chlorophyll content in sweet corn (Zea maysL.) was significantly dropped at higher water stress (40% ETc throughout the crop season) compared to the control (100% ETc)13. The decline in chlorophyll content in I1 at 33 DAP in 2021 and 70 DAP in 2022 could be due to excess water in the soil due to heavy rainfall and irrigation. The saturated soil conditions, as mentioned by Khayatnezhad and Gholamin61, can be susceptible to the reduction in leaf chlorophyll content in our study. Full irrigation, in addition to frequent rainfall, might have contributed to a decline in leaf chlorophyll content for the control I1. Although there was no significant difference in biochar treatments in 2021 (Fig. 4C and D), significant differences were observed at 70 DAP and 90 DAP in 2022 where higher biochar rates were contributing to higher chlorophyll synthesis in cucumber (Fig. 4D). Our finding aligns with a previous study Singh, et al.13that suggested that the hardwood biochar at 13 t/ha increased chlorophyll SPAD reading compared to the control, providing some N and Mg to leaves, and ultimately, enhancing chlorophyll synthesis in sweet corn. The application of biochar soil amendment can increase nutrient supply and uptake by plants by catalyzing biotic and abiotic reactions in the rhizosphere, which help stimulate plant development62. The contribution of biochar in supplying essential nutrients for leaf chlorophyll synthesis in various crops has been reported in different studies63,64. Also, higher Ksat, which eases the water flow in the soil in biochar-amended plots, retained nutrients through physical and chemical means, avoiding leaching65, which plants could uptake for different physiological processes like chlorophyll synthesis.

Stomatal conductance and transpiration

In 2021, at 33 DAP, I4 had the least gs among all the irrigation levels, while the difference in gs remained insignificant among differential irrigations treatments at 62 and 74 DAP (Fig. 5A). In 2022, at 42 DAP, I1 and I2 had comparable gs, which were significantly higher than I3 and I4 (Fig. 5B). At 70 DAP, I3 had significantly higher gs than all three irrigation levels, and at 90 DAP, I1 and I3 had comparable gs, followed by I2, and the least was in I4. Notably, the water stress at 80% ETc at any growth stage of cucumber could maintain similar or even higher gs than full irrigation (100% ETc). Therefore, agreeing with previous reports that highlighted the restriction in the opening of stomata under declining water conditions4,66, our finding also suggests that the cucumber plants likely adapt to water stress or compensate for soil water stress in the root zone imposed by DI level at 80% ETc (i.e., I2 treatment) to maintain similar or higher gs than the control I1 throughout the growing season. Nonetheless, when the irrigation level reached 60% ETc or below, the stomatal conductance in cucumber was lowered, for instance, once the irrigation dropped to 60% ETc at 70 and 90 DAP in 2022 the gs was decreased. A reverse pattern was observed for I3 treatment, where gs was low at the beginning (i.e., 42 DAP)) and increased later (i.e., 70 and 90 DAP) when the irrigation level was maintained at 80% ETc. Biochar treatments did not influence gs responses at different growth stages of cucumber in 2021 and 2022 (Fig. 5C and D).

As shown in Fig. 6A and B, the stomatal closure also reduced transpiration rate (E) of the cucumber plant at 33 DAP in 2021, and 42, 70, and 90 DAP in 2022. The E was significantly lower for I4 treatment at 33 DAP but remained unaffected among DI treatments at 62 and 74 DAP in 2021 (Fig. 6A). A distinct pattern of E to be pointed out in 2022 (Fig. 6B) is that I1 and I2 treatments exhibited comparable E at 42 DAP, and when the second differential irrigation level at 80% ETc was employed to I3, E increased but with 60% ETc, E decreased in I2. Hence, it is envisaged that the transpirational water loss was primarily regulated by stomatal conductance which is dependent on the water availability in leaves and the plant system resulting from different DI levels4. The transpiration loss was more distinct among irrigation levels in 2022 compared to 2021 due to the relatively hotter and drier period in 2022. Biochar treatments did not affect transpiration as there was no difference in stomatal conductance under different biochar application rates (Fig. 6C and D).

Photosynthesis and instantaneous water use efficiency

In 2021, there was comparable net photosynthesis (Pn) between I1 and I3, followed by significantly lower Pn in I2 and the least in I4 at 33 DAP. Still, Pn remained comparable among DI treatments at 62 and 74 DAP (Fig. 7A). In 2022, irrigation levels I1, I2, and I3 had comparable Pn, significantly higher than I4 at 42 DAP (Fig. 7B). At 70 DAP, I3 had the highest Pn followed by I1, and Pn values under I3 and I1 treatments were significantly higher than I2 and I4. The reduced stomatal conductance can be a limiting factor for reduced photosynthetic CO2 assimilation as the intake is constrained by lower water loss in I2 and I4 treatments67,68. At 90 DAP, again, there was no significant difference in Pn among irrigation levels. It is worth noting that I2 treatment for cucumber plants responded favorably by sustaining Pn, i.e., maintaining satisfactory CO2assimilation for most of the growing period under semi-arid climatic conditions. The gs appeared more sensitive than Pn because gs values were significantly affected under water stress conditions, likely leaving Pn unaffected among different DI levels at 90 DAP in 2022. Our finding agreed with the previous studies that the depression in Pn is entirely triggered with the closure of the stomatal aperture69,70. The biochar treatments did not significantly affect Pn in cucumbers in both years (Fig. 7C and D).

Instantaneous WUE (iWUE) was significantly higher in I4 than other irrigation treatments (i.e., I1, I2, and I3) at 33 DAP in 2021, and 42 DAP and 70 DAP in 2022 (Fig. 8A and B). Notably, the percentage decline in gs exceeded the percentage decline in Pn in response to water stress imposed by DI treatments (Figs. 5A-B and 7A-B). The most plausible explanation is that the water stress under different growth stage-based DI treatments largely affects gs (R2 > 0.9) more than Pn (R2< 0.5), which, as also reported in previous studies71, later triggers a reduction in Pn. iWUE increased with increasing water stress levels in different DI treatments, similar to the findings of Singh, et al.13, indicating that cucumber plants under extreme (I4) water stress conditions could exhibit high Pn activity for a given value of gs, resulting in high iWUE. The biochar application rate at 15 t/ha significantly increased iWUE at 33 DAP only in 2021 (Fig. 8C), while it remained unaffected later in the 2021 growing season and throughout the 2022 growing season (Fig. 8D).

Leaf area index, biomass, and yield

Leaf area index significantly differed among irrigation levels throughout the growing season in both years (Fig. 9A and B). LAI started to increase at 33 DAP, reached its peak at 62 DAP, and decreased later except for I3, which continued to increase until 74 DAP in 2021 (Fig. 9A). The DI level I2 had significantly higher LAI at 33 DAP compared to other DI levels, which was comparable to the control I1 at 62 DAP but decreased at 74 DAP. There was a sharp reduction in LAI in I4 beyond 62 DAP in 2021. In 2022, although the highest LAI was observed for I2 at the beginning, I1 had the highest LAI at 70 and 90 DAP (Fig. 9B). The LAI in all the irrigation levels decreased after 70 DAP. The sharp decline in LAI at the later growth stage of the cucumber plant, except I3 in 2021, could be attributed to senescence effects72 in both years. As visualized in Fig. 9A and B, the onset of leaf senescence was relatively rapid for the DI treatment that imposed the most water stress conditions, i.e., I4. Our study showed that I2 at the beginning and I3 at the later growth stage when the irrigation levels were at 80% ETc helped to maintain comparable or even higher LAI than full irrigation (i.e., I1). Similar results were obtained by a previous study in semi-arid West Texas Parkash, et al.4, in which the cucumber plants exposed to irrigation level of 80% of ETc had enhanced leaf area similar to the cucumber plants growing under irrigation level of 100% of ETc. In contrast, differential irrigation was applied at different growth stages in this study, the cucumber plants. exposed to mild water stress conditions (80% ETc) until the mid-season followed by 60% ETc afterward, maintained satisfactory leaf expansion. Apparently, the growth-based DI levels (i.e., I2) evaluated in this study could maintain adequate leaf area or canopy structure of the cucumber plant that would help the plant prepare more photosynthates and allocate assimilates to the developing fruits. The effect of biochar on the LAI of cucumber remained insignificant in both years (Fig. 9C and D).

Different DI levels affected the vegetative dry biomass of cucumber in both years (Table 2). In 2021, irrigation treatments I1, I2, and I3 produced comparable aboveground vegetative dry biomass, while it was the lowest in I4. However, in 2022, compared to I1, I2 only had comparable vegetative dry biomass with I1, whereas the biomass was significantly reduced under I3 and I4 treatments. Singh-Sangwan, Abad Farooqi and Singh Sangwan73mentioned that plants under water stress conditions mobilize the limited water for survival rather than using it for growth. The dry vegetative biomass under I2 compared to I1 might be explained by LAI, an indicator of plant growth and biomass production74. The leaf expansion was similar between I1 and I2 treatments towards the end of the cucumber growing season, which might be the reason why I2 produced similar vegetative dry vegetative biomass compared to I1. Unlike the I2 treatment, the DI level I3, which was subject to more water stress conditions for plants (60% ETc until mid-season), did not maintain biomass accumulation in 2022, as limited water conditions restricted the growth. It can be further explained by the fact that the cucumber plants might experience water stress caused by the DI level of 60% of ETc mainly when the plants were actively growing and requiring enough water for growth before the mid-season. But, switching to DI level of 80% of ETc after the mid-season did not contribute significantly to biomass accumulation because the plants had already assimilated the resources to grow fruits. Compared to I1, the irrigation level I4 significantly reduced vegetative dry biomass by 37% in 2021 and 57% in 2022, indicating that, as also suggested in a previous study4, the cucumber plants under severe water stress (I4) plants undergo growth adjustments as a mechanism to cope with limited water resources. As most of the growth and physiology of the cucumber plants were unaffected by biochar treatments, the vegetative biomass also remained unaffected in both years.

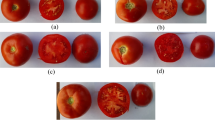

The individual fruit weight is an important determinant of the economic yield of cucumber75. This signifies that the total yield is the function of the sink strength of each fruit. The individual fruit weight was reduced significantly for I2, I3, and I4 treatments by 11, 13, and 27%, respectively, in 2021, but only by 0.5 and 16% for I3 and I4, respectively, in 2022 (Table 2). Alternatively, fruit weight was increased by 5% in I2 in 2022 (Table 2). Our study is in agreement with the findings by Parkash, et al.4where the severe water stress imposed by DI level of 40% of ETc had the largest decrease in average fruit weight of cucumber compared to 100% ETc. It was most likely that, as reported by Abd El-Mageed and Semida76 for cucumber plants, insufficient soil water resulting from DI levels might cause inadequate water and nutrient absorption by cucumber plants that could promote fruit weight. Biochar amendments did not influence the individual fruit weight of the cucumber.

The water stress under different DI treatments significantly affected the yield of cucumber (Table 2). In 2021, the yield penalties in I2, I3, and I4 were 15, 20 and 53%, respectively, but in 2022, the penalties were reduced to 13, 11 and 44%, respectively compared to I1. The average reduction in cucumber yield for the 2021–2022 seasons was 14% for I2, 16% for I3, and 49% for I4 compared to I1. It is noteworthy that the cucumber plants might be sensitive to water stress resulting from the reduced water availability under DI treatment, which could cause yield losses. Nevertheless, the application of DI treatment I2 in the cucumber production system could lead to satisfactory levels of biomass production with less water, i.e., more savings in irrigation water allocation than other DI treatments. Previous studies have also reported yield reductions in cucumbers under DI strategies. For example, Abd El-Mageed, et al.77 showed that DI at 80% ETc replacement did not significantly reduce the yield but a severe decline occurred in 60% ETc water replacement treatments compared to 100% ETc in field-grown cucumber. Another important aspect to be noted is that the yield reductions under growth stage-based DI levels could vary depending on the growth stage at which the ETc deficit was imposed. For example, for the DI treatment I2, 80% ETc until the mid-season followed by 60% after the mid-season had caused a lower, i.e., a 15% yield reduction compared to 60% ETc until mid-season followed by 80% ETc, accounting for a 20% yield reduction in 2021. Mao, et al.17identified the mid-stage of cucumber to be more sensitive than the later stage for water stress impacting yield. Water stress could lead to flower abortion in cucumbers22. When there is higher water stress in cucumbers, the flowers tend to abort, leading to lower yields. As noticed during the routine measurements of plant physiological parameters, until the mid-season, the growth was rapid allowing a higher number of fertile flowers at the nodes. Once it crossed the mid-season, the growth was limited, with fewer nodes producing new flowers.

The biochar treatments 15 t/ha and 20 t/ha increased the yield by 3 and 6%, respectively, in 2021 and by 5% and 8%, respectively, in 2022 compared to the control (0 t/ha). However, the increase in yield was not statistically significant. This minor yield increment could be partially attributed to the enhanced saturated hydraulic conductivity resulting from added biochar amendment, which might regulate infiltration and improve water movement and redistribution of soil water in the root zone, likely influencing adequate root water and nutrient uptakes78.

Conclusions

This study investigated the potential effects of integrating growth stage-based deficit irrigation (DI) levels and biochar application rates on cucumber productivity in semi-arid West Texas. There were no significant interactive effects between irrigation and biochar application on cucumber performance. However, with increased water stress conditions for the plants imposed by comparatively lower DI level treatments at various growth stages (between establishment and mid-season and mid-season and maturity), there was a decline in chlorophyll content, stomatal conductance, transpiration, and net photosynthesis in cucumber. Leaf area index (LAI) and vegetative dry biomass were comparable between I1 and I2, suggesting the adaptability of cucumber plants under DI-imposed water stress conditions by applying irrigation level of 80% of crop evapotranspiration (ETc) until the mid-season followed by irrigation level of 60% of ETc after the mid-season. Yield reductions in cucumbers were only 15 and 20% in I2 and I3, respectively, in 2021, but it narrowed down to 13 and 11% in 2022 compared to I1. The biomass production for DI treatment I2 was similar to I1 (i.e., full irrigation or control treatment), with a minor reduction in cucumber yield and the potential for saving approximately 25% of irrigation water without compromising plant growth and physiological parameters. Therefore, DI levels that maintain moderate water stress conditions for the cucumber plants, especially I2, can be adopted as a promising growth stage-based DI strategy in semi-arid environments such as West Texas. The application of biochar amendment at higher rates (15 and 20 t/ha) significantly increased the saturated hydraulic conductivity for semi-arid soil with relatively higher clay contents in the second growing season. The application of biochar, integrated with growth stage-based DI, showed limited benefits to cucumber growth, physiology, and yield in both growing seasons. Our study provides unique information on managing irrigation for sustainable production of cucumber in water limited regions like West Texas which will help vegetable growers, water users and policy makers to manage water resources. This study also creates an opportunity for soil management using biochar under limited irrigation for vegetable production. However, studies aimed at assessing long-term responses of cucumber are suggested to quantify the potential of integrating biochar and DI strategies for sustaining cucumber production in semi-arid environments.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Cano, A. et al. Current knowledge and future research directions to link soil health and water conservation in the Ogallala aquifer region. Geoderma 328, 109–118 (2018).

Deines, J. M. et al. Transitions from irrigated to dryland agriculture in the Ogallala aquifer: land use suitability and regional economic impacts. Agric. Water Manage. 233, 106061 (2020).

McGuire, V. L. Water-level and recoverable water in storage changes, high plains aquifer, predevelopment to 2015 and 2013–15. (2017).

Parkash, V., Singh, S., Deb, S. K., Ritchie, G. L. & Wallace, R. W. Effect of deficit irrigation on physiology, plant growth, and fruit yield of cucumber cultivars. Plant. Stress. 1, 100004 (2021a).

Gençoğlan, C., Altunbey, H. & Gençoğlan, S. Response of green bean (P. vulgaris L.) to subsurface drip irrigation and partial rootzone-drying irrigation. Agric. Water Manage. 84, 274–280 (2006).

Kirda, C. Deficit irrigation scheduling based on plant growth stages showing water stress tolerance. Food Agricultural Organ. United Nations Deficit Irrig. Practices Water Rep. 22 (2002).

Ruiz-Sanchez, M. C., Domingo, R. & Castel, J. R. Deficit irrigation in fruit trees and vines in Spain. A review. Span. J. Agricultural Res. 8, S5–S20 (2010).

Potop, V. Assessment of water deficit and or surplus during growing period of vegetable crops in Polabí. Meso-climate Microclimate Landsc. Struct. Anthropogenic Environ. Rock. Mill. 2 (2011).

Cakir, R. Effect of water stress at different development stages on vegetative and reproductive growth of corn. Field Crops Res. 89, 1–16 (2004).

Seidel, S., Werisch, S., Schütze, N. & Laber, H. Impact of irrigation on plant growth and development of white cabbage. Agric. Water Manage. 187, 99–111 (2017).

Nangare, D., Singh, Y., Kumar, P. S. & Minhas, P. Growth, fruit yield and quality of tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill.) as affected by deficit irrigation regulated on phenological basis. Agric. Water Manage. 171, 73–79 (2016).

Geerts, S. & Raes, D. Deficit irrigation as an on-farm strategy to maximize crop water productivity in dry areas. Agric. Water Manage. 96, 1275–1284 (2009).

Singh, M. et al. Biochar implications under limited irrigation for sweet corn production in a semi-arid environment. Front. Plant Sci. 13, 1032 (2022).

Makino, A., Sato, T., Nakano, H. & Mae, T. Leaf photosynthesis, plant growth and nitrogen allocation in rice under different irradiances. Planta 203, 390–398 (1997).

Nemeskéri, E. & Helyes, L. Physiological responses of selected vegetable crop species to water stress. Agronomy 9, 447 (2019).

Parkash, V. et al. Effect of deficit irrigation on root growth, soil water depletion, and water use efficiency of cucumber. HortScience 56, 1278–1286 (2021b).

Mao, X. et al. Effects of deficit irrigation on yield and water use of greenhouse grown cucumber in the North China plain. Agric. Water Manage. 61, 219–228 (2003).

Tower, S. The best dill in Texas the agriculturist. Tex. Tech. Univ. (2017).

USDA. Vegetables 2022 Summary. National Agricultural Statistics Service. (2023).

Amer, K. H., Midan, S. A. & Hatfield, J. L. Effect of deficit irrigation and fertilization on cucumber. Agron. J. 101, 1556–1564 (2009).

Rahil, M. & Qanadillo, A. Effects of different irrigation regimes on yield and water use efficiency of cucumber crop. Agric. Water Manage. 148, 10–15 (2015).

Oliveira, E. C., Carvalho, J. A., Silva, W. G., Rezende, F. C. & Almeida, W. F. d. Effects of water deficit in two phenological stages on production of Japanese cucumber cultived in greenhouse. Engenharia Agrícola. 31, 676–686 (2011).

Alomran, A., Louki, I., Aly, A. & Nadeem, M. Impact of deficit irrigation on soil salinity and cucumber yield under greenhouse condition in an arid environment. (2013).

Agbna, G. H. et al. Effects of deficit irrigation and Biochar addition on the growth, yield, and quality of tomato. Sci. Hort. 222, 90–101 (2017).

Fazal, A. & Bano, A. Role of plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR), Biochar, and chemical fertilizer under salinity stress. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 47, 1985–1993 (2016).

Karhu, K., Mattila, T., Bergström, I. & Regina, K. Biochar addition to agricultural soil increased CH4 uptake and water holding capacity–Results from a short-term pilot field study. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 140, 309–313 (2011).

Singh, M., Saini, R. K., Singh, S. & Sharma, S. P. Potential of integrating Biochar and deficit irrigation strategies for sustaining vegetable production in water-limited regions: A review. HortScience 54, 1872–1878 (2019).

Blanco-Canqui, H. Biochar and soil physical properties. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 81, 687–711 (2017).

Filiberto, D. M. & Gaunt, J. L. Practicality of Biochar additions to enhance soil and crop productivity. Agriculture 3, 715–725 (2013).

Kambo, H. S. & Dutta, A. A comparative review of Biochar and hydrochar in terms of production, physico-chemical properties and applications. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 45, 359–378 (2015).

Liu, Z. et al. Effects of Biochar amendment on rapeseed and sweet potato yields and water stable aggregate in upland red soil. Catena 123, 45–51 (2014).

Lehmann, J., Gaunt, J. & Rondon, M. Bio-char sequestration in terrestrial ecosystems–a review. Mitig. Adapt. Strat. Glob. Change. 11, 403–427 (2006).

Sorensen, R. B. & Lamb, M. C. Crop yield response to increasing Biochar rates. J. Crop Improv. 30, 703–712 (2016).

Ali, A. Enhancement of depleted loam soil as well as cucumber productivity utilizing Biochar under water stress. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 50, 49–64 (2019).

Valani, G. P., Martíni, A. F., Pezzopane, J. R. M., de Campos Bernardi, A. C. & Cooper, M. Soil physical quality in the topsoil of integrated and non-integrated grazing systems in a Brazilian ferralsol. Soil Tillage. Res. 220, 105357 (2022).

Gamage, D. V., Mapa, R., Dharmakeerthi, R. & Biswas, A. Effect of rice-husk Biochar on selected soil properties in tropical Alfisols. Soil. Res. 54, 302–310 (2016).

Toková, L., Igaz, D., Horák, J. & Aydin, E. Effect of Biochar application and re-application on soil bulk density, porosity, saturated hydraulic conductivity, water content and soil water availability in a silty loam haplic luvisol. Agronomy 10, 1005 (2020).

TAMU. Historic ETo Reference. College Station, TX: TAMU. (2021).

NCSS. Lubbock Series. USDA., (2010). https://soilseries.sc.egov.usda.gov/OSD_Docs/L/LUBBOCK.html

Gee, G. W. & Bauder, J. W. Particle-size analysis. Methods Soil. Analysis: Part. 1 Phys. Mineralogical Methods. 5, 383–411 (1986).

Singh, A. et al. Simulation of root zone soil water dynamics under cotton-silverleaf nightshade interactions in drip-irrigated cotton. Agric. Water Manage. 288, 108479 (2023).

Zotarelli, L., Dukes, M. D., Romero, C. C., Migliaccio, K. W. & Morgan, K. T. Step by step calculation of the Penman-Monteith evapotranspiration (FAO-56 Method). Inst. Food Agricultural Sci. Univ. Fla. 8 (2010).

Brouwer, C. & Heibloem, M. Irrigation water management: irrigation water needs. Train. Man. 3, 1–5 (1986).

Kharel, G. et al. Effect of Long-Term semiarid pasture management on soil hydraulic and thermal properties. Plants 12, 1491 (2023).

Team, R. C. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria (2013).

de Mendiburu, F. Agricolae tutorial version 1.2-2. Stat. Inf. Department Economic Fac. Natl. Univ. Agric. Molina Peru 78 pp (2015).

Ajibola, O. V. & Amujoyegbe, B. J. Effect of seasons, mulching materials, and fruit quality on a cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.) variety. Asian J. Agricultural Hortic. Res. 3, 1–11 (2019).

Reynolds, W., Bowman, B., Brunke, R., Drury, C. & Tan, C. Comparison of tension infiltrometer, pressure infiltrometer, and soil core estimates of saturated hydraulic conductivity. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 64, 478–484 (2000).

Zhou, H. et al. Biochar enhances soil hydraulic function but not soil aggregation in a sandy loam. Eur. J. Soil. Sci. 70, 291–300 (2019).

Asai, H. et al. Biochar amendment techniques for upland rice production in Northern Laos: 1. Soil physical properties, leaf SPAD and grain yield. Field Crops Res. 111, 81–84 (2009).

Lim, T., Spokas, K., Feyereisen, G. & Novak, J. Predicting the impact of Biochar additions on soil hydraulic properties. Chemosphere 142, 136–144 (2016).

Wang, K. et al. Biochar application alters soil structure but not soil hydraulic conductivity of an expansive clayey soil under field conditions. J. Soils Sediments. 21, 73–82 (2021).

Jačka, L., Trakal, L., Ouředníček, P., Pohořelý, M. & Šípek, V. Biochar presence in soil significantly decreased saturated hydraulic conductivity due to swelling. Soil Tillage. Res. 184, 181–185 (2018).

Ouyang, L., Wang, F., Tang, J., Yu, L. & Zhang, R. Effects of Biochar amendment on soil aggregates and hydraulic properties. J. Soil. Sci. Plant. Nutr. 13, 991–1002 (2013).

Gavili, E., Moosavi, A. A. & Haghighi, A. A. K. Does Biochar mitigate the adverse effects of drought on the agronomic traits and yield components of soybean? Ind. Crops Prod. 128, 445–454 (2019).

Langeroodi, A. R. S., Mancinelli, R. & Radicetti, E. Contribution of Biochar and arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi to sustainable cultivation of sunflower under semi-arid environment. Field Crops Res. 273, 108292 (2021).

Pandey, R., Maranville, J. & Chetima, M. Deficit irrigation and nitrogen effects on maize in a Sahelian environment: II. Shoot growth, nitrogen uptake and water extraction. Agric. Water Manage. 46, 15–27 (2000).

Széles, A. V., Megyes, A. & Nagy, J. Irrigation and nitrogen effects on the leaf chlorophyll content and grain yield of maize in different crop years. Agric. Water Manage. 107, 133–144 (2012).

Ercoli, L., Lulli, L., Mariotti, M., Masoni, A. & Arduini, I. Post-anthesis dry matter and nitrogen dynamics in durum wheat as affected by nitrogen supply and soil water availability. Eur. J. Agron. 28, 138–147 (2008).

Mansouri-Far, C., Sanavy, S. A. M. M. & Saberali, S. F. Maize yield response to deficit irrigation during low-sensitive growth stages and nitrogen rate under semi-arid Climatic conditions. Agric. Water Manage. 97, 12–22 (2010).

Khayatnezhad, M. & Gholamin, R. The effect of drought stress on leaf chlorophyll content and stress resistance in maize cultivars (Zea mays). Afr. J. Microbiol. Res. 6, 2844–2848 (2012).

Joseph, S. et al. How Biochar works, and when it doesn’t: A review of mechanisms controlling soil and plant responses to Biochar. Gcb Bioenergy. 13, 1731–1764 (2021).

Liu, M. et al. Effects of Biochar with inorganic and organic fertilizers on agronomic traits and nutrient absorption of soybean and fertility and microbes in purple soil. Front. Plant Sci. 13, 871021 (2022).

Minhas, W. A. et al. Synergetic use of Biochar and synthetic nitrogen and phosphorus fertilizers to improves maize productivity and nutrient retention in loamy soil. J. Plant Nutr. 43, 1356–1368 (2020).

Gelardi, D. L. et al. M. Biochar alters hydraulic conductivity and impacts nutrient leaching in two agricultural soils. Soil 7 (2021).

Liu, F., Jensen, C. R. & Andersen, M. N. Hydraulic and chemical signals in the control of leaf expansion and stomatal conductance in soybean exposed to drought stress. Funct. Plant Biol. 30, 65–73 (2003).

Ahumada-Orellana, L., Ortega-Farías, S., Poblete-Echeverría, C. & Searles, P. S. Estimation of stomatal conductance and stem water potential threshold values for water stress in Olive trees (cv. Arbequina). Irrig. Sci. 37, 461–467 (2019).

Chaves, M. M. et al. How plants Cope with water stress in the field? Photosynthesis and growth. Ann. Botany. 89, 907 (2002).

Bolla, A., Voyiatzis, D., Koukourikou-Petridou, M. & Chimonidou, D. Photosynthetic parameters and cut-flower yield of Rose ‘Eurored’(HT) are adversely affected by mild water stress irrespective of substrate composition. Sci. Hort. 126, 390–394 (2010).

Sharma, S., Leskovar, D. & Crosby, K. Genotypic differences in leaf gas exchange and growth responses to deficit irrigation in reticulatus and Inodorus Melons (Cucumis Melo L). Photosynthetica 57 (2019).

Asargew, M. F., Masutomi, Y., Kobayashi, K. & Aono, M. Water stress changes the relationship between photosynthesis and stomatal conductance. Sci. Total Environ. 907, 167886 (2024).

Akmal, M., Rehman, H., Farhatullah, M. A. & Akbar, H. Response of maize varieties to nitrogen application for leaf area profile, crop growth, yield and yield components. Pak. J. Bot. 42, 1941–1947 (2010).

Singh-Sangwan, N., Farooqi, A. & Singh Sangwan, R. Effect of drought stress on growth and essential oil metabolism in lemongrasses. New Phytol. 128, 173–179 (1994).

Liang, Y. et al. Improved Estimation of aboveground biomass in rubber plantations by fusing spectral and textural information from UAV-based RGB imagery. Ecol. Ind. 142, 109286 (2022).

Marcelis, L. Fruit growth and biomass allocation to the fruits in cucumber. 1. Effect of fruit load and temperature. Sci. Hort. 54, 107–121 (1993).

Abd El-Mageed, T. A. & Semida, W. M. Organo mineral fertilizer can mitigate water stress for cucumber production (Cucumis sativus L). Agric. Water Manage. 159, 1–10 (2015).

Abd El-Mageed, T. A., Semida, W. M., Taha, R. S. & Rady, M. M. Effect of summer-fall deficit irrigation on morpho-physiological, anatomical responses, fruit yield and water use efficiency of cucumber under salt affected soil. Sci. Hort. 237, 148–155 (2018).

Nweke, I. & Nsoanya, L. Effect of cowdung and Urea fertilization on soil properties, growth, and yield of cucumber (Cucumis sativus L). J. Agric. Ecol. Res. Int. 3, 81–88 (2015).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the Specialty Crop Block Grant Program of Texas Department of Agriculture for funding this study. We thank Dr. Azeezahmed Shaik, Dr. Atinderpal Singh, Gary, Nelson, and Bryan for their assistance in field work. We appreciate the help from Lelton and the Quaker Research Farm crew. We also thank the Department of Plant and Soil Science for providing the resources and facilities for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: A.K., S.S.; Methodology: A.K.; Data collection: A.K., M.S., P.B.; Data Curation: A.K.; Software and Analysis: A.K.; Writing -Original draft preparation: A.K.; Supervision: S.S.; Review and editing: S.S., M.S., S.D., C.S., G.R. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kafle, A., Singh, S., Singh, M. et al. Influence of deficit irrigation and biochar amendment on growth, physiology, and yield of cucumber in West Texas. Sci Rep 15, 9615 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-94113-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-94113-y