Abstract

Gait impairment, which is commonly observed in stroke survivors, underscores the imperative of rehabilitating walking function. Wearable inertial measurement units (IMUs) can capture gait parameters in stroke patients, becoming a promising tool for objective and quantifiable gait assessment. Optimal sensor placement for stroke assessment that involves optimal combinations of features (kinematics) is required to improve stroke assessment accuracy while reducing the number of sensors to achieve a convenient IMU scheme for both clinical and home assessment; however, previous studies lack comprehensive discussions on the optimal sensor placement and features. To obtain an optimal sensor placement for stroke assessment, this study investigated the impact of IMU placement on stroke assessment based on gait data and clinical scores of 16 stroke patients. Stepwise regression was performed to select the kinematics most correlated with stroke assessment (lower limb part of Fugl-Meyer assessment). Sensors at different locations were combined into 28 sensor groups and their stroke assessment was compared. First, the reduced number of gait features does not significantly impact the stroke assessment. Second, the selected gait parameters by stepwise regression are found all from sensors at the hip and bilateral thighs. Last, a three-sensor scheme–sensors at the hip and bilateral thighs was suggested, which achieved a high accuracy with an adjusted R2 = 0.999, MAE = 0.07, and RMSE = 0.08. Further, the prediction error is zero if the predicted lower limb Fugl-Meyer scales are rounded to the nearest integer. These findings offer a convenient IMU solution for quantitatively assessing stroke patients. Therefore, the IMU-based stroke assessment provides a promising complementary tool for clinical assessment and home rehabilitation of stroke patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Stroke, also referred to as a cerebrovascular accident or brain infarction, is a serious medical condition caused by vascular lesions in the cerebral arterial system1. It is associated with high rates of incidence, disability, mortality, and recurrence, posing a substantial socioeconomic burden2. Globally, it is estimated to be the third leading cause of death3. This condition impairs various brain functions4, predominantly affecting the contralateral side of the body. Stroke-induced upper motor neuron syndrome results in various sensorimotor deficits, including muscle weakness, motor control, spasticity, and proprioceptive impairments. These deficits significantly affect the functional use of the arm5 and the mobility of the lower limbs6. Hemiplegic gait is the most common motor impairment observed after a stroke. It is characterized by unilateral weakness on the hemiplegic side, resulting in inter-limb asymmetry, abnormal trunk tilt and rotation, and a dragging gait7. Temporally, hemiplegic gait is characterized by reduced walking speed8, prolonged stride duration, and decreased stride frequency9,10. Spatially, it is defined by asymmetry in stride length, with the hemiplegic side typically showing a longer stride than the unaffected side6. After rehabilitation, approximately 20% of stroke patients remain unable to walk11. Even among those who regain walking ability, gait patterns often remain abnormal due to spasticity and changes in muscle mechanical properties, which may lead to further impairments over time12. Restoring ambulation is a primary goal for stroke patients. This requires the use of validated gait assessment tools to design personalized rehabilitation plans and assess treatment efficacy. At the same time, stroke rehabilitation is a long-term process that traditionally requires patients to stay in the hospital, often making it labor-intensive and costly. In comparison, home rehabilitation and telemedicine provide more cost-effective and convenient alternatives.

In the clinical assessment of stroke patients, commonly used scales, such as Fugl–Meyer Assessment13 and Berg Balance Scale14, may overlook critical gait characteristics. As a result, they may fail to objectively and comprehensively reflect the patient’s overall condition. Moreover, these scales often rely on subjective judgments and clinician experience, which can hinder their ability to provide objective and quantifiable gait assessment15. Although clinicians can evaluate patients’ gait performance and improvement in walking function using vision-based gait analysis16, the validity, reliability, specificity, and sensitivity of these methods have been questioned17,18. Subjective observational gait scales are often used for the evaluation of certain spatiotemporal and/or kinematic gait parameters. However, they are typically inadequate for analyzing the multifaceted aspects of gait variability and complexity19. In this context, sensor-based measurement has been proposed as a method to provide objective and precise gait data20. Patterson et al. used the pressure mat (GaitRite™, CIR Systems, Clifton, NJ) to collect gait data from stroke patients and healthy subjects. They analyzed spatiotemporal gait parameters to evaluate gait symmetry21 and further investigated long-term gait disorders post-stroke, focusing on parameters such as velocity and symmetry22. Although widely used in experimental research and clinical practice, this approach is unaffordable and limited to ground-based tasks, making it less suitable for home rehabilitation. Wallard et al.23 employed an optical motion analysis system (VICON—Oxford Metrics, Oxford, UK) to quantify the gait of hemiplegic patients before and after robotic rehabilitation, aiming to verify the efficacy of the intervention. Similarly, Ferrari et al.7 utilized six VICON cameras as a reference standard to validate the accuracy, consistency, and correlation of gait parameters and patterns recorded by a single RGB-D sensor during a short walk. Although optical motion capture systems are considered the gold standard for precise spatiotemporal and motion analysis24, their high cost and bulky size hinder their use in both laboratory and clinical environments25. Therefore, there is a need for a method that is easy to operate, cost-effective, time-efficient, and accurate for home rehabilitation.

In recent years, the advancement of microelectromechanical systems (MEMS) has enabled the widespread use of wearable sensors. Their compact size, affordability, and user-friendly design make them suitable for applications in both laboratory and clinical environments19. The wearable sensors have been used in fall detection26,27, motion monitoring28, motion recognition29, and quantitative assessment30. Zhao et al.31 developed a quantitative monitoring tool for the rehabilitation process by employing a wearable IMU-based method for analyzing and evaluating hemiplegic gait. Their approach utilized a gradient descent algorithm (GDA) for gesture reconstruction and a weighted dynamic time warping (WDTW) algorithm to calculate gait discrepancies. Tsakanikas et al.32 used IMU sensors to collect gait data and applied feature extraction techniques combined with machine learning methods to assess gait impairment and identify Parkinsonian gait disorders. Gujarathi et al.33 collected leg motion data using IMU sensors placed on both shanks and derived individual gait parameters with a correlated gait analysis algorithm to monitor rehabilitation progress. Seo et al.34 performed a principal component analysis of trunk movement (TM) and gait event (GE) parameters from IMU sensors to characterize gait in hemiplegic patients. Previous studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of such systems in detecting and analyzing gait abnormalities, evaluating treatment efficacy, and monitoring the rehabilitation process of patients. However, the number of IMUs in most of the prior studies is limited and information from all sensors is used. There are no comprehensive discussions on IMU placement for stroke assessment. It remains uncertain which sensors contribute the most to stroke assessment.

Optimal sensor placement for stroke assessment, including the selection of key kinematic features, is essential to improve accuracy while minimizing the number of sensors required. This study introduces an IMU-based method for accurately assessing stroke patients by identifying critical gait features and determining optimal IMU placement. A comprehensive analysis was performed on the effects of various gait features and IMU placements on stroke assessment. By simplifying and optimizing sensor placements, we proposed a convenient and reliable three-sensor scheme, using IMUs placed on the hip and bilateral thighs, which achieved high accuracy. This method provides a complementary tool to traditional observational approaches, reducing subjectivity and enhancing the objectivity of stroke assessment and rehabilitation.

Results

This study focuses on the quantitative assessment of stroke patients through gait kinematics measured using wearable IMUs. IMUs placed at different locations were combined into 28 groups, and stepwise regression was applied for feature selection. At last, the optimal features were identified as those measured from sensors at the hip and bilateral thighs, showing a strong correlation with clinical assessments (lower limb section of Fugl–Meyer Assessment). Reducing the number of sensors does not compromise the accuracy of stroke assessment; hence, a three-sensor scheme (hip and bilateral thighs) is proposed for precise gait evaluation in both clinical and home rehabilitation settings. The IMU-based stroke assessment method demonstrates high accuracy in clinical evaluations and holds promise as a valuable complementary tool for the clinical assessment and home rehabilitation of stroke patients. With the advent of new sensor technologies, this quantitative IMU-based approach is expected to find broader and more extensive applications in gait assessments.

Feature selection

The number of occurrences of feature selection across all sensor groups, as determined by stepwise regression, was counted (Fig. 1). Gait parameters selected more than five times along with their corresponding sensor locations, are presented in Table 1. Both Fig. 1 and Table 1 highlight five key features: UnUpLeg-Sensor-Gyro-z, UnUpLeg-Bone-Quat-y, Hips-Sensor-Quat-w, UpLeg-Sensor-Quat-w, and Hips-Bone-Quat-x. These features represent the angular velocities and quaternions of the thigh on the unaffected side, as well as quaternions of the hip and the thigh on the affected side. This finding underscores the critical role of sensors placed at the hip and bilateral thighs in the accurate assessment of stroke patients.

IMU placement optimization

The estimation performances of various sensor groups were evaluated using the adjusted R2, MAE, and RMSE metrics, as summarized in Table 2.

In Groups XXVII, and XXVIII, no features were selected by the stepwise regression

Table 2 shows that Group I achieves nearly perfect fitting results, with adjusted R2 = 1, MAE = 0, and RMSE = 0. However, the Pearson correlation coefficient (Fig. 2) and the variance inflation factor (VIF, Table 3) among the features in this group remain notably high. The collinearity between the features is strong, which could lead to overfitting. Therefore, Group I is excluded from consideration as the optimal group.

The other groups exhibit varying levels of estimation performances. For instance, Groups V, VI, and X demonstrate excellent goodness of fit, with adjusted R2 values of 0.999, along with MAE and RMSE below 0.1, indicating minimal prediction errors. While Groups II, III, IV, IX, and XVI exhibit relatively high goodness of fit values, they still display significant differences when compared to Groups V, VI, and X (Table 4). The remaining groups, however, present lower adjusted R2 and higher MAE and RMSE values, reflecting inadequate prediction performances.

Discussion

Feature selection plays a pivotal role in model construction for this study, ensuring that selected gait features accurately reflect the stroke conditions of patients. To reduce the collinearity among the features, the assessment results were compared before and after limiting the number of included features to 10 for all groups. As shown in Table 8, the overall model evaluation performance did not significantly decrease when the number of included features was limited to 10.

The results also indicate that certain kinematic parameters are frequently selected by stepwise regression, highlighting their potential importance in identifying altered movement patterns in stroke patients. These gait parameters are measured using sensors located at the hip and thigh, offering valuable insights for optimizing IMU placement.

Neurological disorders, such as stroke, often have a significant impact on patients’ motor functions, severely affecting their quality of life. Assessing motor function, particularly through gait data, provides an objective and precise evaluation, which is essential for developing personalized rehabilitation programs. Standardized data processing ensures more consistent comparisons between patients, thereby enhancing the guidance for implementing and adjusting rehabilitation treatments. The IMU-based wearable mocap system enables the collection of multidimensional motion data, including gait, posture, and trajectory. These data are not only for assessing patient’s motor functions and rehabilitation progress but also for subsequent data analyses. By employing data analysis methods, including machine learning and statistical analysis, a quantitative evaluation of the patient’s condition can be made, enhancing the understanding of trends in motor function, rehabilitation progress, and potential issues.

In motion capture, particularly for gait analysis, IMUs are widely preferred due to their high accuracy, compact size, low power consumption, and cost-effectiveness. This study explores the impact of different IMU placements on model performance for stroke assessment. Table 4 summarizes the model evaluation results for IMU locations where the adjusted R2 is greater than 0.9. The goal was to identify IMU placements that minimize the number of sensors required while achieving excellent prediction accuracy. IMUs at various locations were combined into 28 groups, and the optimal gait features and sensor placements were determined through stepwise regression analysis.

The modeling performances of different sensor groups were compared and quantified by calculating the adjusted R2, MAE, and RMSE between the predicted and true values (lower limb part of the Fugl–Meyer Assessment). Some sensor groups, such as Group I, exhibited overfitting or strong collinearity issues. In Contrast, other groups showed more generalized tendens, with relatively robust fitting capabilities and a lower risk of overfitting. Considering the balance between cost-effectiveness and performance, Group X emerged as a relatively optimal choice. Figure 3 shows the prediction results for Group X, which achieved high accuracy with an adjusted R2 = 0.999, MAE = 0.07, and RMSE = 0.08 (see Table 4). Additionally, the prediction error would be zero if the predicted lower limb Fugl–Meyer Assessment were rounded to the nearest integer. Group X uses only three sensors (placed on the hip and bilateral thighs) to effectively assess stroke patients’ conditions. Despite the limited number of sensors, the high accuracy of this configuration makes it practical for everyday use. This three-sensor scheme can assist physicians in conducting more objective clinical assessments and also support home rehabilitation evaluations.

In summary, this study tackles the challenges of low time efficiency and lack of objectivity in clinical scale assessments by employing wearable IMUs to quantitatively evaluate the motor function of stroke patients. By integrating feature selection, regression analysis, and sensor placement optimization, this proposed approach delivers accurate gait assessments using fewer sensors, thereby simplifying clinical evaluations, reducing assessment times, and enabling remote rehabilitation. Selecting optimal features and sensor placements, it provides both scientific and personalized guidance for neurological rehabilitation, offering healthcare professionals deeper insights into motor impairments and supporting the development of targeted rehabilitation strategies.

Methods

Participants and procedure

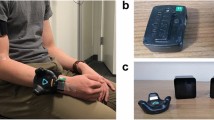

Sixteen stroke patients were randomly recruited based on the inclusion criteria. The gait experiments were conducted at the Department of Rehabilitation Medicine, Affiliated Haikou Hospital of Xiangya Medical College, starting in May 2022. The participants included eleven males and five females, aged between 47 and 68 years, with stroke onset ranging from 1 to 24 months, and lower limb Fugl–Meyer Assessment scores between 10 and 32 (out of a maximum score of 34). Table 5 presents the demographic details of the participants, who were selected based on the following specific inclusion criteria: a confirmed stroke diagnosis via CT or MRI; consent from both patients and their family members to understanding the experiment; adequate competence and understanding the experiment; adequate cognitive and executive functions; and the ability to independently walk at least 20 m. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Affiliated Haikou Hospital, Xiangya Medical College (Registration no: SC2022088). All experiments were conducted in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

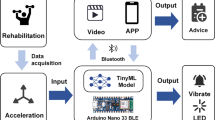

Wearable mocap system

The gait experiments were conducted using a wearable sensor mocap system (Perception Neuron 3 Pro, Beijing Noitom Technology Co., Ltd.), which consisted of 17 IMUs, elastic straps, and data transmission modules. The system’s wireless nine-axis MEMS inertial sensors included built-in accelerometers, gyroscopes, and magnetometers. It operates with a measurement delay of less than 25 ms and a sampling rate of 60 Hz. Data transmission to the receiver in real-time via a 2.4 GHz wireless network.

In the experiment, seven IMUs were strategically attached to predetermined anatomical locations on the participants’ bodies using elastic straps: head, shoulder blades, upper back, upper arms, forearms, lower back (hip), thighs, shanks, and feet. Since the primary focus of this study was to evaluate the lower limb functions of the patients, only the lower limb data were extracted for analyses (Fig. 4). To ensure accurate mapping of the IMU data to individualized body models, subjects underwent postural calibrations while standing.

Experimental design

Before the experiments, all participants were briefed on the study’s purpose and procedures, and informed consent was obtained from each individual. A professional clinician then assessed each patient using the Fugl–Meyer Assessment. Subsequently, a 10-m walking test was administered on level ground (in a hospital corridor) to record the gait data using a wearable IMU-based mocap system. Each participant completed five trials of the walking test, with adequate rest periods provided between the trials.

The Fugl-Meyer Assessment is a clinical tool designed to evaluate functional recovery in the upper and lower extremities of stroke patients, playing a critical role in rehabilitation therapy by providing reliable support and guidance for assessors. It is organized into five categories: motor function, sensory function, balance, joint range of motion, and joint pain. Each category includes multiple items, with each item rated on a three-point scale based on task performance: 0 = unable to perform, 1 = partially able to perform, and 2 = fully able to perform. The motor component’s lower extremity score assesses hip, knee, and ankle motion, coordination, and reflex movements, with a maximum total score of 34 points. Studies by Kim et al.35 and Crow et al.36 have confirmed that the Fugl-Meyer Assessment demonstrates strong inter-rater reliability and consistency, offering a dependable framework and accurate measurements for rehabilitation therapy. As a result, the FMA is widely used in both clinical practice and research as a reliable tool for monitoring rehabilitation progress in stroke patients.

Feature extraction and grouping

This study involves two types of gait data: joint angles and original sensor data. The joint angles were recorded based on conventional definitions of human skeletal kinematics, encompassing movements in three dimensions for each joint. The hip and ankle joints exhibit a total of six movements: flexion, extension, internal rotation, external rotation, adduction, and abduction. In contrast, only flexion and extension were considered in the knee joint. The original sensor data comprise original measurements captured by the sensors, including quaternions, angular velocities, accelerations, and displacements (as shown in Table 6).

To mitigate the influences of variations in step speed, step length, and joint angles, the following pre-processing steps were performed: the walking data from the first and last three gait cycles of each trial were excluded, along with data from two gait cycles before and after each turn. This ensured that joint angles for each participant’s trials were based on complete gait cycles and excluded data immediately before and after turning. The entire gait dataset was then compiled by concatenating data from the trials of different participants. For the range of motion (RoM) of each joint, the peaks and valleys of the joint angles were determined using a peak detection algorithm. For the original sensor data, step length was determined by calculating the difference in the z-components of successive foot positions.

To evaluate the contribution of different IMUs to the stroke assessments, sensors placed at different locations were grouped into 28 distinct sensor groups. Table 7 presents the gait parameters associated with each sensor group as follows:

-

Group I included all seven sensors on the lower limbs.

-

Group II included a lumbar sensor and sensors at three locations on the affected lower limb: thigh, shank, and foot.

-

Group III included three locations on the affected lower limb: thigh, shank, and foot.

-

Groups IV–XV (12 groups in total) each included a lumbar sensor and were differentiated by the placement of sensors on either the affected or bilateral lower limbs. Specifically, Groups IV, V, VI, X, XI, and XII included sensors on the affected lower limb, whereas Groups VII, VIII, IX, XIII, XIV, and XV included sensors on both lower limbs.

-

Groups XVI–XXI included two sensors on either the bilateral or affected side and did not include the hip sensor.

-

Groups XXII–XXVIII, each included only a single sensor placed at different positions.

It is important to note that the joint angles and joint velocities were obtained only when sensors were worn concurrently at two adjacent body locations. For instance, the hip angle was obtained when sensors were worn simultaneously at the hip and thigh locations. These 28 groups, with varying numbers and locations of sensors aimed to provide comprehensive insights into the influences of sensor placements on stroke assessment.

Stepwise regression

The data were processed and statistically analyzed using Python (PyCharm 2021.1.3) and SPSS (version 26.0, IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Regression analysis was conducted using bidirectional elimination, with the sum of features for each group as the input and the lower limb part of the Fugl–Meyer Assessment as the output. This process identified the optimal subset of features for each sensor group, resulting in optimal fitting equations and adjusted R2. Stepwise regression, a feature selection method37, incrementally builds an optimal predictive model by adding or removing variables and assessing their statistical significance at each iteration. Note that the significance of introducing features should be lower than that of their removal. Thus, the criterion for feature inclusion was set at p < 0.05 and that for exclusion was p > 0.1. This ensures the selection of features with statistically significant contributions to the output while eliminating variables with lesser impacts. The correlation coefficients of the selected features were employed to compare the regression results, facilitating the assessment of the model performance.

In stepwise regression feature selection, collinearity among features is mitigated by constraining the number of features included in the model. To evaluate this approach, we compared models with and without a feature limit, setting the maximum number of features at 10 (Table 8). Pearson correlation coefficients between features were calculated, using Groups I, VI, and X as examples, and the results were visualized in a heat map (Fig. 5). Before limiting the number of features included, the heat map exhibits numerous dark-colored areas, indicating strong collinearity. After feature selection, this collinearity was effectively mitigated. Additionally, the comparisons showed that model performance was not significantly affected, indicating that reducing the number of features did not compromise interpretability or prediction accuracy.

Data evaluation

The adjusted R2, MAE, and RMSE values were calculated to evaluate the stepwise regression prediction results. These metrics were then used to comprehensively assess the model’s fit and predictive performance. Among them, the adjusted R2 goodness of the model’s goodness of fit to the data, while the MAE and RMSE quantify prediction errors, with smaller values reflecting high prediction accuracy. Together, these measures provide an effective assessment of the model’s ability to fit the data and predict outcomes accurately.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Lo, E. H., Dalkara, T. & Moskowitz, M. A. Mechanisms, challenges and opportunities in stroke. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 4, 399–414 (2003).

Chunhua, T., Lu, G., Qiong, L. & Lili, Z. Interpretation on the report of global stroke data 2022. J. Diagnostics Concepts Pract. 22, 238 (2023).

Naghavi, M. et al. Global burden of 288 causes of death and life expectancy decomposition in 204 countries and territories and 811 subnational locations, 1990–2021: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet 403, 2100–2132 (2024).

Chemerinski, E. & Robinson, R. G. The neuropsychiatry of stroke. Psychosomatics 41, 5–14 (2000).

Gowland, C., deBruin, H., Basmajian, J. V., Plews, N. & Burcea, I. Agonist and antagonist activity during voluntary upper-limb movement in patients with stroke. Phys. Ther. 72, 624–633 (1992).

Krasovsky, T. & Levin, M. F. Toward a better understanding of coordination in healthy and poststroke gait. Neurorehabil. Neural Repair 24, 213–224 (2010).

Ferraris, C. et al. Monitoring of gait parameters in post-stroke individuals: A feasibility study using rgb-d sensors. Sensors 21, 5945 (2021).

Goldie, P. A., Matyas, T. A. & Evans, O. M. Deficit and change in gait velocity during rehabilitation after stroke. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 77, 1074–1082 (1996).

Woolley, S. M. Characteristics of gait in hemiplegia. Topics Stroke Rehabil. 7, 1–18 (2001).

Bohannon, R. Gait performance of hemiparetic stroke patients: selected variables. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 68, 777–781 (1987).

Balaban, B. & Tok, F. Gait disturbances in patients with stroke. Pm&r 6, 635–642 (2014).

Olney, S. J. & Richards, C. Hemiparetic gait following stroke. Part I: Characteristics. Gait Posture 4, 136–148 (1996).

Meyer, A. F., Jaasko, L., Leyman, I., Olsson, S. & Steglind, S. The post stroke hemiplegic patient. I. A method for evaluation of physical performance. Scand. J. Rehabil. Med. 7, 13–31 (1975).

Berg, K., Wood-Dauphine, S., Williams, J. & Gayton, D. Measuring balance in the elderly: preliminary development of an instrument. Physiother. Canada 41, 304–311 (1989).

Toro, B., Nester, C. & Farren, P. A review of observational gait assessment in clinical practice. Physiother. Theory Pract. 19, 137–149 (2003).

Daly, J. et al. Development and testing of the Gait Assessment and Intervention Tool (GAIT): a measure of coordinated gait components. J. Neurosci. Methods 178, 334–339 (2009).

Ferrarello, F. et al. Tools for observational gait analysis in patients with stroke: a systematic review. Phys. Ther. 93, 1673–1685 (2013).

Turani, N., Kemiksizoğlu, A., Karataş, M. & Özker, R. Assessment of hemiplegic gait using the Wisconsin Gait Scale. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 18, 103–108 (2004).

Mohan, D. M. et al. Assessment methods of post-stroke gait: A scoping review of technology-driven approaches to gait characterization and analysis. Front. Neurol. 12, 650024 (2021).

Nadeau, S., Betschart, M. & Bethoux, F. Gait analysis for poststroke rehabilitation: the relevance of biomechanical analysis and the impact of gait speed. Phys. Med. Rehabil. Clin. 24, 265–276 (2013).

Patterson, K. K., Gage, W. H., Brooks, D., Black, S. E. & McIlroy, W. E. Evaluation of gait symmetry after stroke: a comparison of current methods and recommendations for standardization. Gait Posture 31, 241–246 (2010).

Patterson, K. K., Gage, W. H., Brooks, D., Black, S. E. & McIlroy, W. E. Changes in gait symmetry and velocity after stroke: a cross-sectional study from weeks to years after stroke. Neurorehabil. Neural Repair 24, 783–790 (2010).

Wallard, L., Dietrich, G., Kerlirzin, Y. & Bredin, J. Effects of robotic gait rehabilitation on biomechanical parameters in the chronic hemiplegic patients. Neurophysiologie Clinique/Clinical Neurophysiol. 45, 215–219 (2015).

Cuesta-Vargas, A. I., Galán-Mercant, A. & Williams, J. M. The use of inertial sensors system for human motion analysis. Phys. Ther. Rev. 15, 462–473 (2010).

Krebs, D. E., Edelstein, J. E. & Fishman, S. Reliability of observational kinematic gait analysis. Phys. Ther. 65, 1027–1033 (1985).

Schwickert, L. et al. Fall detection with body-worn sensors: a systematic review. Zeitschrift für Gerontologie Geriatrie https://doi.org/10.1007/s00391-013-0559-8 (2013).

Habib, M. A. et al. Smartphone-based solutions for fall detection and prevention: challenges and open issues. Sensors 14, 7181–7208 (2014).

Yang, C.-C. & Hsu, Y.-L. A review of accelerometry-based wearable motion detectors for physical activity monitoring. Sensors 10, 7772–7788 (2010).

Chernbumroong, S., Cang, S. & Yu, H. A practical multi-sensor activity recognition system for home-based care. Decision Support Syst. 66, 61–70 (2014).

Carpinella, I., Cattaneo, D. & Ferrarin, M. Quantitative assessment of upper limb motor function in Multiple Sclerosis using an instrumented Action Research Arm Test. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 11, 1–16 (2014).

Zhao, H. et al. Analysis and evaluation of hemiplegic gait based on wearable sensor network. Inform. Fusion 90, 382–391 (2023).

Tsakanikas, V. et al. Evaluating gait impairment in Parkinson’s disease from instrumented insole and IMU sensor data. Sensors 23, 3902 (2023).

Gujarathi, T. & Bhole, K. Gait analysis using imu sensor. in 2019 10th International Conference on Computing, Communication and Networking Technologies (ICCCNT). 1–5 (IEEE).

Seo, J.-W. et al. Principal characteristics of affected and unaffected side trunk movement and gait event parameters during hemiplegic stroke gait with IMU sensor. Sensors 20, 7338 (2020).

Kim, H. et al. Reliability, concurrent validity, and responsiveness of the Fugl-Meyer Assessment (FMA) for hemiplegic patients. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 24, 893–899 (2012).

Crow, J. L. & Harmeling-Van Der Wel, B. C. 2008 Hierarchical properties of the motor function sections of the Fugl-Meyer assessment scale for people after stroke: a retrospective study. Physical therapy 88, 1554–1567 (2008).

Wilkinson, L. & Dallal, G. E. Tests of significance in forward selection regression with an F-to-enter stopping rule. Technometrics 23, 377–380 (1981).

Funding

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 32360196, 32260244, and 32160204), the Project of Sanya Yazhou Bay Science and Technology City (No.SCKJ-JYRC-2023–26 and SCKJ-JYRC-2023–27), the Key R&D Project of Hainan Province (Grant No. ZDYF2022SHFZ302, ZDYF2022SHFZ275, and ZDYF2025SHFZ027), Hainan Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (324RC448 and 824CXTD424), Hainan Province Clinical Medical Center (No: 0202067), South China Sea Rising Star Project of Hainan Province, and Joint Program on Health Science & Technology Innovation of Hainan Province (WSJK2025QN046).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YS and ZS contributed to the conception, investigation, and original draft of the study. LM was involved in the data collection. Bl, contributed to the manuscript editing. YS wrote the first draft of the manuscript. Fl, MY andDW supervised the whole project and reviewed the manuscript, All authors contributed to the articleand approved the submitted version.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Institutional review board statement

This experiment was approved by the Ethics Committee of Haikou People’s Hospital (Register no.: SC2022088).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sun, Y., Song, Z., Mo, L. et al. IMU-Based quantitative assessment of stroke from gait. Sci Rep 15, 9541 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-94167-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-94167-y

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Cloud–edge collaborative AI for symmetry and asymmetry in human motion understanding and collaboration

Journal of Cloud Computing (2025)

-

IMU-based segmental root mean square analysis of gait in individuals with cerebellar ataxia: a pilot cross-sectional study

Scientific Reports (2025)