Abstract

Aiming at the problem of surrounding rock control during the 52,102 working face passing through the roof fall area of return air roadway in lijiahao coal mine. Through on-site investigations, numerical simulations, and engineering practices, we analyzed the characteristics and causes of roof fall along the rib of the goaf. Based on the Mohr–Coulomb criterion, a numerical model was established, identifying influencing factors, and proposing an early intervention pressure relief control technology centered on "proactive avoidance." Determined the starting position and the staggered distance of the avoiding roadway. The study indicates that: (1) The deformation of the surrounding rock in the roof fall roadway is mainly affected by high static loads, mining pressure, mechanical properties of the surrounding rock, and the effect of pressure relief. The optimal timing for implementing the best prevention technology is to stop mining and excavate an avoidance roadway when the working face is 20 m away from the roof fall area. At the same time, based on safety and economic principles, determine the distance between the avoiding roadway and the original roadway is 20 m to shorten the length of the working face. After passing through the avoidance roadway, resume the use of the original roadway to ensure economic benefits. (2) Early proactive intervention pressure relief technology effectively reduces the deformation of the roadway surrounding rock, decreasing the amount of deformation on both sides by about 11%, verifying its effectiveness and practicality.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The formation mechanism of roof falls is complex, involving factors such as geological structures, rock mechanical properties, and mining techniques. Scholars have made progress through theoretical analysis and numerical simulations. However, in specific scenarios such as the working face has passed through the roof caving area of the return airway, the evolution patterns of roof falls have not been systematically elucidated, hindering effective prevention and control.

Wang et al. identified high horizontal tectonic stress and fault slip induced by mining as the driving forces behind roadway deformation and roof collapse; Gao et al. proposed controlling roof collapse by enhancing surrounding rock shear strength and reducing fracture permeability; Zhang et al. established calculation formulas based on the collapse size of the surrounding rock fracture zone, revealing the relationship between boundary horizontal force distribution and burial depth1,2,3. Pan et al. propose the concept, mechanism, and classification of rock burst and roof collapse composite disasters in deep roadways, revealing their occurrence mechanism and highlighting the importance of softening and rupture zones in stability control for dynamic disaster prevention4. Wang et al. and other scholars have found that the main influencing factors of roof caving and spalling include fissure water, damaged rock mass, and human error5,6,7. Liu et al. study revealed that the method of evaluating the hidden dangers of roof collapse through roof structure detection and exploration technology is highly similar to the actual situation of underground roof strata8. Ray et al. and other scholars identified that the “cutting” phenomenon of surrounding rock before roof caving and the influence of upper coal seam mining on the periodic weighting step distance of the lower coal seam are critical factors leading to poor roof stability in close-distance coal seam groups9,10. Fattahi et al. predicted roof caving rates using algorithms, highlighting coal mine roof rating’s importance; Bieniawski et al. demonstrated geomechanical classification’s effectiveness in roof quality evaluation; Park et al. identified rock mass quality and humidity changes as critical factors influencing circular roadway roof caving risks11,12,13,14. Wang et al. and other scholars research put forward a range of methods that could be used to evaluate the risk of coal mine roof collapse, and at the same time, these methods could help identify the main risk factors15,16,17. Jin et al. proposed a semantic modeling system for sharing and reusing roof fall accident knowledge to enable intelligent decision-making, while Ding et al. highlighted the significant impacts of backfill mining, roof beam disturbance, and gob-side entry retention on roof collapse and coal seam stability under varying mining conditions18,19,20,21,22. Huo et al. investigated the evolution of top coal drawing characteristics to improve recovery rates, while Jia et al. studied collapse column failure, surrounding rock control, overburden fracture development, roadway over-excavation prediction, column stability, and induced caving technology, providing theoretical and technical support for safe mining23,24,25,26,27,28. Du et al. developed an analysis model and methods to enhance the accuracy of evaluating surrounding rock pressure and rock mass strength in shallow-buried and biased roadways, including solutions for deflection functions, movement laws of artificial roofs, and an optimized Hoek–Brown criterion29,30,31,32. Hu et al. proposed a new method for roof control using induced caving, Li et al. validated designs for pillar stability, backfill unloading warning models, and the impact of coal seam dip on pillar strength33,34,35,36, Shi et al. improved mining efficiency through optimized layout and techniques, offering theoretical and practical guidance for safe and efficient mining37,38. Wang et al. study focused on simulating rock mechanical properties and improving parameter calibration methods using enhanced particle swarm and jellyfish swarm algorithms. It also developed a prediction model for rock strength and analyzed the impact of fractures, joints, and holes on rock behavior through compression experiments, offering insights for rock mass stability and fracture analysis39,40,41,42,43,44,45.

In summary, this review highlights various aspects of underground coal mine roof fall accidents and large roadway deformation, including geological conditions, tectonic stresses, fault movements, support methods, and compound disaster mechanisms. Each study contributes valuable insights into understanding these complex issues but requires further verification and refinement. Future research should focus on detailed experimental methods and results descriptions, cross-disciplinary collaborations to achieve more comprehensive prevention strategies.

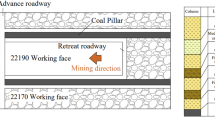

The mining roadway of the working face at Lijiahao Coal Mine employs a double roadway excavation method. Following the completion of mining at the 52,101 working face, the adjacent 52,102 working face is required to utilize the pre-completed roadway. However, upon opening this roadway, a significant issue was identified: it had been adversely affected by the mining activities at the 52,101 working face, resulting in a substantial roof collapse within the mining roadway. The collapsed area measured 10 m in length, 9 m in height, and 5.5 m in width, exhibiting an irregular triangular prism shape, as illustrated in Fig. 1. This occurrence has severely impacted the mining operations at the 52,102 working face. This article examines the deformation and failure mechanisms of the surrounding rock within the roof collapse area of the mining roadway, particularly as the mining working face progresses through the roadway. The study employs theoretical analysis, numerical simulation, and on-site monitoring methods to investigate the evolution model of the roof failure zone during the advancement of the working face, as well as the factors influencing the occurrence and development of roof collapse damage. Ultimately, a rational mining plan is proposed based on these findings, which offers valuable guidance for the successful mining operations at the working face.

The evolution pattern of surrounding rock stress and plastic zone as the working face advances through the roof fall area

This paper uses the FLAC3D software to simulate and analyze the roof fall disaster in the 51,109 return air roadway of Lijiahao Coal Mine, establishing a numerical calculation model of mining face, and analyzed the changes of stress field, displacement field and plastic zone in the roof fall area during the mining process.

Establishment

-

(1)

Geometric model.

In geological engineering, accurate and reasonable model establishment is crucial for numerical simulation calculations and analysis. The choice of model size must consider actual conditions, as its dimensions and internal division strategy affect computational efficiency and precision. The roof fall disaster at Lijiahao Coal Mine affected stope work, with the shape and size of the roof fall area shown in Fig. 1, and the site situation depicted in Fig. 2.

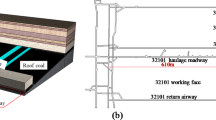

In the study, overlying rock layers above 200 m were simplified to a vertical stress of 10.35 MPa, acting at the 200 m depth in the model. The model dimensions were set to 300 m × 404 m × 150 m to balance computational precision and efficiency, ensuring reliable analysis results. The geometric model is shown in Fig. 3.

-

(2)

Determination of mechanical parameters

The roof fall zone in Lijiahao Coal Mine occurs at the 51,109 return airway, serving the 52,102 working face’s ventilation. Coal seam: + 1280 m elevation, 4.2 m thickness, 2° dip, 570 m depth. Surrounding rock properties tested (Table 1), with stratigraphic column distribution shown (Fig. 4).

Experiments revealed rock mass mechanical properties. The Mohr–Coulomb model incorporated internal friction angle/cohesion parameters to simulate complex behaviors and characterize stress–strain relationships, establishing an engineering-reliable numerical model (Fig. 4) for design/safety evaluation.

Simulation conditions and analysis plan

According to the relative position of the working face and the roof caving area, the stress variation in the middle part of the roof caving area when the working face is pushed to be tangent to the roof caving area is selected as the research object. This position can comprehensively observe the overall trend of stress variation, explore the interaction between the advancement of the working face and the concentrated stress of roof caving under different stress conditions, so as to provide strong data support for engineering design-related work and safety evaluation. At the same time, select the roadways where no roof caving has occurred as the comparison group, so as to accurately identify the specific impact of roof caving on stress distribution.

Analysis of simulation results

Stress evolution pattern as the working face advances through the roof fall area

-

(1)

Analysis scheme model.

Study on the influence of roof fall on the stress distribution of roadways, select the middle position of the roof fall area and the vertical section of the roadway trend and the vertical section of the roadway trend without roof fall as the observation objects, by comparing the stress changes with the working face advancing towards the above two sections, reveal the influence degree and law of roof fall on the stress state of roadways, and provide scientific support for preventive measures and response strategies (Fig. 5).

-

(2)

Analysis the impact of roof falls on the surrounding stress field.

In the control group, stress development extends outward, whereas this phenomenon was not observed in the roof fall group and the range was shortened by 4 m. Preliminary analysis shows that roof falls lead to stress concentration, shifting stress to the roof fall area, affecting its stability and the stress state of surrounding rock masses. The vertical impact range increases due to the rise in roof fall, adding to the support burden and effecting the stability of the roadway. In the numerical model, 15 stress measurement points were distributed within the stress reduction range of the caving roadway and the non-caving positive side, and the observed stress evolution trend is shown in Fig. 6. The stress evolution of the caving roadway is more unstable compared to the non-caving roadway and produces stress concentration.

As the working face nears the collapsed zone, increasing pressure causes rock deformation and instability. This alters stress distribution patterns: the collapsed area shows a small V-shaped stress concentration (> 10 m) on the working face side, while the intact area exhibits a larger U-shaped pattern. Distinct stress elevation zones and symmetrical reduction zones emerge post-collapse, as shown in Fig. 5a–c.

In the stress analysis of Fig. 7, when the working face is 20 m away from the roof fall area, the stress impact is gradual. When the distance is less than 20 m, the superposition effect of the stress field significantly increases complexity, potentially threatening the stability and safety of the working face. Therefore, in practical engineering, measures should be taken before advancing the working face to within 20 m of the roof fall area to mitigate the impact, reduce the adverse effects of stress superposition, and ensure safe and stable advancement.

Evolution pattern of the plastic zone in the roof fall area during working face advancement

To study plastic zone evolution, cross-sections at the mid-collapse zone were analyzed when the working face became tangent to the collapsed area. Comparative modeling with intact roadways revealed collapse-induced mechanisms governing plastic zone development.

Main conclusions on the impact of roof falls on the plastic zone: As the working face advances, the plastic zone expands toward the sidewall, with significant outward expansion in the collapsed group but none in the control group; the vertical height of the plastic zone increases, showing a 1:1 relationship with the height of the roof fall area; the surrounding rock of the roof fall area is continuously affected by shear stress, showing a significant difference from the control group. The area and disturbance range of the plastic zone expand, forming an approximately elliptical disturbance circle in the roof fall group; the rocks around the roadway do not form a traditional stress reduction zone; instead, the development of the plastic zone may exacerbate the risk of roof falls and trigger rock bursts and other mine pressure problems, as shown in Fig. 8.

The development of the plastic zone and stress concentration are key factors affecting roadways in roof fall events, leading to rock deformation, crack propagation, strength reduction, and structural damage to the roof. These changes exacerbate the risk of mine pressure disasters in roadways, such as rock bursts. To prevent and control such disasters, it is necessary to avoid the core impact of the plastic zone, ensuring the stability and safety of the roadway.

Principles of surrounding rock control in the roof fall area during working face advancement

Monitoring points arranged via cross-shaped layout at mid-axis positions of the collapsed zone and equivalent control group. Point A in the collapsed zone was positioned at the roof collapse apex, with three groups (each containing two measurement pairs across both roadways, comprising points A/B/C/D) detailed in Fig. 9.

Based on the measurement points in Fig. 9, as the working face advances 20 m from the original roof fall area, analyze the changing trend of the relative displacement of the top and bottom plates and both sides under different coal pillar widths measured in the model. Create deformation trend graphs as shown in Fig. 10.

Analysis of stress distribution diagrams suggests: stress redistribution caused by roof collapse events during working face advancement. A “proactive avoidance” centered prevention and control technology is proposed: suspend mining activities and excavate new roadways to avoid impact. At the same time, coal pillars are retained for support. Observations indicate small stress fluctuations at the working face 10 m away, requiring special attention to the stability of this area.

Technology for surrounding rock control during working face advancement through the roof fall area

Analysis of the deformation and failure mechanism of surrounding rock in roadways within roof fall areas

The analysis model reveals the displacement field, stress field, and load redistribution of the arch structure under advanced support pressure. The stress concentration in the roof fall area, the trend of displacement changes, and load redistribution are influenced by high static loads, mining pressure, surrounding rock mechanical properties, and the effect of pressure relief. Comparing the load distribution at different positions can analyze the redistribution situation. An increase in load near the working face side may indicate that the failure is extending in that direction. Failure extension is caused by a reduction in the strength and stability of the rock or coal body, which may lead to an increase in the area of the roof fall area, reduce stability, and increase safety risks. It is necessary to adjust the mining strategy to ensure safe passage.

Proposal of control technology

-

(1)

Goals and factors to consider.

Aiming to assure mine gallery stability, mitigate the risks associated with roof collapses, and sustain financial viability; key considerations encompass geological circumstances, patterns of roof fall propagation, interactions between existing and newly constructed passages, along with an evaluation of the shortcomings inherent in conventional shoring techniques. As mining fronts approach regions with prior roof falls, the formation of plastic zones under significant compression and concentrated stresses could lead to neighboring rock masses giving way or exacerbating roof fall incidents, wherein inadequate support systems might precipitate safety incidents.

-

(2)

Simulation steps and methods.

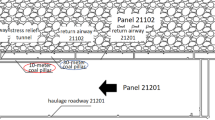

Construct a three-dimensional geological model to ascertain the physical characteristics of the rock strata. On the basis of this model, choose the locations to avoid tunnels and their spacing, for example, 5 m, 10 m, 15 m, and 20 m, and evaluate the stability of these arrangements. Employ FLAC3D software to emulate the tunnel excavation process, as shown in Fig. 11.

-

(3)

Conclusions and recommendations.

In the design, select areas with minimal deformation and uniform stress distribution to ensure reasonable spacing. As the working face progresses, the extent of damage to the rib side and roof increases, posing a risk of toppling due to the use of supports in the original roadway. It is recommended to implement a new strategy: cease mining activities 20 m in front of the goaf area, excavate a new roadway at least 20 m away from the old one, while retaining a coal pillar wider than 20 m, and resume mining after reducing the length of the working face by 25.5 m. This solution has been proven effective, but monitoring should be intensified and construction plans adjusted according to geological conditions.

Engineering practice

With the reduction of the working face, to prevent the repeated excavation of the roadway, new plastic failure zones appear in the surrounding rock, which overlap with the effects of the old roadway. Deformation analysis identifies roadway damage depth/distribution, evaluating current support efficacy and guiding future designs. On-site stress/deformation monitoring captures roadway sidewall convergence and roof subsidence. Baseline points at centerline and waist positions (Fig. 12) enable tri-daily data collection. Monitoring points divided into three groups, each containing three pairs distributed across three roadways, with each pair comprising four points (A/B/C/D).

The monitoring results indicate that the stress evolution pattern from the numerical simulation is consistent with the actual situation. The trend of on-site roadway deformation is shown in Fig. 13, demonstrating that the proposed control scheme has achieved good results in practical applications. It effectively reduces the relative displacement of surrounding rock deformation, stabilizes the surrounding rock stress, and minimizes the amount of deformation on both sides by approximately 11%, verifying the effectiveness and practicality of this technology.

Conclusion

-

(1)

When the working face advances to the roof fall area and crosses its range, under high static loads, due to the development of plastic zones on both sides of the roof fall area and stress concentration towards the working face side, the impact load from the stope will trigger the release of accumulated stress concentration in this area. Additionally, the rotation of old roof rock blocks will lead to the dumping of surrounding rocks or further roof falls and other disasters. If support is used in the roof fall roadway within the roof fall area, it may lead to the occurrence of support dumping accidents. The solution proposed in this paper is safer and more effective, better ensuring economic benefits.

-

(2)

To effectively control the impact of working face mining on the roof fall area, an active intervention pressure relief prevention and control technology centered on the concept of “active avoidance” is proposed. By excavating an avoidance roadway to circumvent the high stress concentration effect of the roof fall area, the avoidance roadway performs the functions of the original return roadway, ensuring the smooth progress of mining activities.

-

(3)

The working face should stop mining operations at least 20 m away from the roof fall area. After the working face stabilizes, excavate an avoidance roadway and shorten the working face. The avoiding distance should be no less than 25 m to avoid the high stress concentration effect of the roof fall area. Simultaneously, excavating the avoidance roadway will form a coal pillar, which can play a role in bearing and isolating, protecting the safety of the newly excavated roadway and working face.

-

(4)

Avoidance Roadway Stability Monitoring and Waiting Period: After the completion of the avoidance roadway excavation, strict stability monitoring must be implemented, and a reasonable waiting period should be set, recommended to be no less than 20 days. This ensures the full stabilization of the roadway structure, providing safety assurance for the initiation of subsequent mining activities.

-

(5)

Future research should integrate roadway avoidance and roof support advantages, investigating their synergistic effects to develop integrated control strategies that mitigate surrounding rock deformation and secondary disasters, establishing theoretical foundations for field operations.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files. The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are not publicly available due commissioned by Lijiahao Coal Mine for confidential research and processing by Professor Shi Zhanshan but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Wang, H. et al. Field investigation of a roof fall accident and large roadway deformation under geologically complex conditions in an underground coal mine. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 51, 1863–1883. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00603-018-1425-1 (2018).

Gao, R., Xia, H., Fang, K. & Zhang, C. Dome roof fall geohazards of full-seam chamber with ultra-large section in coal mine. Appl. Sci. 9, 3891. https://doi.org/10.3390/app9183891 (2019).

Zhang, G. et al. Characteristics of roof collapse of mining tunnels in the fault fracture zone and distribution of the boundary force of the accumulation body. Sustainability 14, 16811. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142416811 (2022).

Pan, Y., Dai, L., Li, G. & Li, Z. Study on compound disaster of rock burst and roof falling in coal mines. J. China Coal Soc. 46(1), 112–122 (2021).

Wang, J. et al. Study on the controller factors associated with roof falling and ribs spalling in deep mine with great mining height and compound roof. Eng. Fail. Anal. 129, 105723. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engfailanal.2021.105723 (2021).

Wang, Y.-J., Zhao, L.-S. & Xu, Y.-S. Analysis of characteristics of roof fall collapse of coal mine in Qinghai Province. China. Appl. Sci. 12, 1184. https://doi.org/10.3390/app12031184 (2022).

Direk, C. Risk Assessment by Fault Tree Analysis of Roof and Rib Fall Accidents in an Underground Hard Coal Mine (Middle East Technical University, 2015).

Liu, H., Ma, N., Gong, P., Zhang, C. & Zhao, H. The technology research about hidden danger identification of tunnel roof fall. Proc. Eng. 26, 1220–1224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proeng.2011.11.2294 (2011).

Influence of cutting sequence and time effects on cutters and roof falls in underground coal mine—numerical approach, Ray, Anil Kumar. West Virginia University ProQuest Dissertations & Theses, 3377510 (2009).

Wang, Y. et al. Study on the destabilization and deformation breakage characteristics of the mine roof under repetitive mining of close coal seam group. Comp. Part. Mech. 11, 1503–1516. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40571-023-00706-7 (2024).

Fattahi, H., Ghaedi, H. & Armaghani, D. J. Optimizing underground coal mine safety: leveraging advanced computational algorithms for roof fall rate prediction and risk mitigation. Min. Metall. Explor. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42461-024-01101-3 (2024).

Bieniawski, Z.T., Rafia, F., Newman, D.A. Ground control investigations for assessment of roof conditions in coal mines. In Paper presented at the The 21st U.S. Symposium on Rock Mechanics (USRMS), Rolla, Missouri (1980).

Park, D. & Michalowski, R. L. Three-dimensional roof collapse analysis in circular tunnels in rock. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 128, 104275. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmms.2020.104275 (2020).

Yasidu, U. M. et al. Influences of water vapor on roof fall accidents in selected underground coal mines in Malawi. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2019, 1–17 (2019).

Wang, Y. J., Lyu, H. M. & Shen, S. L. Rapid determination of fuzzy number in FAHP and assessment risk in coal mine roof fall. Geomat. Nat. Hazards Risk. https://doi.org/10.1080/19475705.2023.2184670 (2023).

Adoko, A. C., Kaisa, N. B. Development of an expert system for unplanned fall of ground assessment in coal mine excavation intersections. In Paper Presented at the 57th U.S. Rock Mechanics/Geomechanics Symposium, Atlanta, Georgia, USA. https://doi.org/10.56952/ARMA-2023-0585 (2023).

Isleyen, E. & Duzgun, H. S. Use of virtual reality in underground roof fall hazard assessment and risk mitigation. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 29(4), 603–607. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmst.2019.06.003 (2019).

Jin, L., Liu, Q. & Geng, Y. Ontology-based semantic modeling of coal mine roof caving accidents. Processes 11, 1058. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr11041058 (2023).

Ding, K. et al. Investigation of the mechanism of roof caving in the Jinchuan Nickel Mine, China. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 51, 1215–1226. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00603-017-1374-0 (2018).

Ding, P. et al. Effect on top-coal mass failure under load-unload induced by shield support. Processes 2024, 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr12091872 (1872).

Yang, Y. et al. Numerical investigation of the influence of roof-cutting parameters on the stability of top coal gob-side entry retaining by roof pre-fracturing in ultra-thick coal seam. Energies 16, 4788. https://doi.org/10.3390/en16124788 (2023).

Huo, Y., Zhu, D., Wang, Z. & Song, X. Numerical investigation of top coal drawing evolution in longwall top coal caving by the coupled finite difference method-discrete element method. Energies 14, 219. https://doi.org/10.3390/en14010219 (2021).

Jia, C. et al. Failure characteristics and control technology of surrounding rock during roadway passing collapse column. Sci. Rep. 14, 28687. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79311-4 (2024).

Lv, X. et al. Fracture field evolution law of mining overburden rock under double-roof-cutting and retaining roadway conditions: a physical analog model and numerical simulation, 18 November 2024, PREPRINT (Version 1) available at Research Square. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-5266676/v1.

Fattahi, H., Nejati, H. R. & Ghaedi, H. Optimizing tunnel excavation: intelligent algorithms for accurate overbreak prediction. Min. Metall. Explor. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42461-024-01074-3 (2024).

Fattahi, H. et al. Accurate Estimation of Bearing Capacity of Stone Columns Reinforced: An Investigation of Different Optimization Algorithms (Elsevier, 2024). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.istruc.2024.106519.

Al, H. M. Feedback of the empirical approach to design the room and pillar mines-Application on Chalk Mines (France). ISRM EUROCK 2016, 689–694. https://doi.org/10.1201/9781315388502-119 (2016).

Chen, Q., Gan, Q., Wang, H. & Liu, C. A new combined mining method: the stope limit length calculation of considering bulk support boundary. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2024, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00603-024-03865-y (2024).

Du, J. M., Fang, Q., Hai, L., Mai, H. Y. & Wang, G. Calculation method for surrounding rock pressure of shallow tunnel with asymmetrical pressure of variable slopes. J. Cent. South. Univ. 52, 4088–4098. https://doi.org/10.11817/j.issn.1672-7207.2021.11.029 (2021).

Guo, X. et al. The Reissner-Ritz method for solving the deflection function of the crown pillar in the stope and its application in the crown pillar failure analysis. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00603-024-03810-z (2024).

He, S. Q. & Ren, Q. F. Mechanical model of artificial roof overlay deformation elastic thin plate. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 504(1), 012024. https://doi.org/10.1088/1757-899X/504/1/012024 (2019).

Hoek, E. & Brown, E. T. The Hoek-Brown failure criterion and GSI-2018 edition. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 11(03), 445–463. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrmge.2018.08.001 (2019).

Hu, J. H. et al. Numerical analysis of application for induction caving roof. J. Cent. South Univ. Technol. 12(Suppl 1), 146–149. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11771-005-0389-y (2005).

Li, X. B., Peng, D. X., Feng, F. & Li, X. S. Stability analysis of horizontal insulating pillar in deep mining from caving to filling method on the basis of refined plate theory. J. China Univ. Min. Technol. 48(3), 484–494. https://doi.org/10.13247/j.cnki.jcumt.001003 (2019).

Liu, C. et al. Construction of filling body instability failure warning model under single-side unloading condition. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 55(7), 4257–4269. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00603-022-02864-1 (2022).

Rashed, G., Slaker, B., Sears, M. M. & Murphy, M. M. A parametric study for the effect of dip on stone mine pillar stability using a simplified model geometry. Min. Metall. Explor. 38, 967–977. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42461-021-00394-y (2021).

Shi, D., Wang, Y., Zhang, C., Fu, T. & Zhang, H. Optimization of efficient mining method in mechanized pan area of FengShan copper mine. Metal Mine. 6, 40–44. https://doi.org/10.19614/j.cnki.jsks.202306006 (2023).

Skrzypkowski, K. Decreasing mining losses for the room and pillar method by replacing the inter-room pillars by the construction of wooden cribs filled with waste rocks. Energies 13(14), 3564. https://doi.org/10.3390/en13143564 (2020).

Wang, M. et al. A calibration framework for the microparameters of the DEM model using the improved PSO algorithm. Adv. Powder Technol. 32(2), 358–369. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apt.2020.12.015 (2021).

Wang, M. & Wan, W. A new empirical formula for evaluating uniaxial compressive strength using the Schmidt hammer test. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 123, 104094. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmms.2019.104094 (2019).

Wang, M., Wan, W. & Zhao, Y. Prediction of the uniaxial compressive strength of rocks from simple index tests using a random forest predictive model. Comptes Rendus Mécanique. 348(1), 3–32. https://doi.org/10.5802/crmeca.3 (2020).

Wang, M., Wan, W. & Zhao, Y. Experimental study on crack propagation and the coalescence of rock-like materials with two preexisting fissures under biaxial compression. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 79, 3121–3144. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10064-020-01759-1 (2020).

Wang, M., Lu, Z., Zhao, Y. & Wan, W. Experimental and numerical study on peak strength, coalescence and failure of rock-like materials with two folded preexisting fissures. Theor. Appl. Fract. Mech. 125, 103830. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tafmec.2023.103830 (2023).

Wang, M., Lu, Z., Zhao, Y. & Wan, W. Peak strength, coalescence and failure processes of rock-like materials containing preexisting joints and circular holes under uniaxial compression: Experimental and numerical study. Theor. Appl. Fract. Mech. 125, 103898. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tafmec.2023.103898 (2023).

Wang, M. et al. Calibrating microparameters of DEM models by using CEM, DE, EFO, MFO, SSO algorithms and the optimal hyperparameters. Comp. Part. Mech. 11, 839–852. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40571-023-00656-0 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number 52004118; Department of Education of Liaoning Province, grant number LJ2020QNL009.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.S. and H.Z.; Methodology, H.Z.; Validation, J.W.; Investigation, Z.S. and H.Z.; Data Curation, H.Z.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, Z.S.; Writing—Review and Editing, Z.S. and H.Z.; Visualization, B.Q.; Supervision, J.H.; Project Administration, Z.S.; Funding Acquisition, Z.S.; Resources, B.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shi, Z., Wang, J., Hao, J. et al. Proactive intervention depressurization control for pre-mining roof fall and mining impacts. Sci Rep 15, 10719 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-94191-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-94191-y

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Roof collapse in a retained top coal roadway induced by high-energy seismic events: implications from a case study

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Primary rupture law of main roof in long-wall face based on principal bending moment

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Research process and hotspot prediction of deep-hole presplitting blasting technology in China’s mines

Geomechanics and Geophysics for Geo-Energy and Geo-Resources (2025)