Abstract

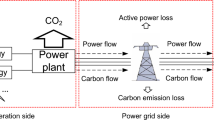

Global climate change is one of the major environmental challenges faced today, and carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions is the primary cause of global warming. Although many countries have committed to reducing carbon emissions and achieving carbon neutrality, progress in reducing emissions across various industries remains uncertain. To address this issue, this study employs advanced machine learning methods such as random forest, extreme gradient boosting (XGBoost), and stacked regression to construct a dynamic correlation model for exploring the relationship between sectoral electricity consumption and urban average CO2 column concentration (XCO2). By combining time-rolling window techniques, the model dynamically reveals temporal correlations between sector-specific electricity consumption and urban XCO2. The performance of the dynamic correlation model was validated with sectoral electricity consumption and urban XCO2 data from 16 cities between 2017 and 2021. The model achieved a coefficient of determination (R2) of up to 0.864 and an root mean square error (RMSE) of 1.350. The study revealed that the model significantly outperformed the traditional random forest and XGBoost models in terms of prediction accuracy, effectively capturing the complex relationship between sectoral electricity consumption and carbon concentration. The correlation between electricity consumption in different industries and XCO2 exhibited significant temporal fluctuations across cities. Through time-rolling analysis, the study revealed sector-specific influences, providing valuable insights for developing more precise and industry-targeted carbon reduction policies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Global climate change is one of the most critical environmental challenges of our time1. The emission of greenhouse gases, especially carbon dioxide (CO2), is the primary cause of global warming, which severely affects ecosystems, human health, and economic activities2,3. In response to the growing threat of climate change, countries worldwide have committed to reducing carbon emissions and achieving carbon neutrality4,5,6. As a result, pollution reduction and carbon mitigation have become top priorities for governments and various industries globally7,8.

Despite these concerted efforts, progress in reducing pollution and carbon emissions remains uncertain, and the effectiveness of current strategies is often unclear5,9. This uncertainty stems in part from the lack of a comprehensive technological framework to assess and guide pollution reduction across different sectors10. The ability to evaluate the effectiveness of emission reduction measures is further hindered by the complexity and diversity of sectoral impacts on carbon emissions11,12,13. Existing studies on carbon reduction efforts have focused on three main approaches:

High-resolution Monitoring: Numerous studies have utilized advanced monitoring technologies, such as satellite remote sensing14, drone-based monitoring15, and ground sensor networks16, to track carbon emissions with high spatial and temporal resolution. These approaches can identify major emission sources and carbon hotspots. However, data integration remains a significant challenge because of inconsistencies in spatial and temporal resolution across different data sources. Additionally, the sheer volume of high-resolution data makes processing and analysis more difficult, limiting its practical utility for guiding targeted pollution reduction strategies17,18.

Economic–Environmental Models: Many studies have attempted to model the relationship between carbon emissions and economic activities through economic–environmental models19,20,21,22,23. These models, which relate emissions to factors such as industrial production, transportation, and energy consumption in buildings, are useful for assessing the broader economic drivers of carbon emissions. However, practical limitations, such as data gaps and regional variability in economic activities, limit the accuracy of these models. The complexity of the relationship between economic activities and emissions further complicates the development of a universal model that can provide reliable guidance for diverse regions and industries24,25,26.

Machine Learning and Big Data Technologies: Machine learning (ML) and big data technologies have emerged as powerful tools for analyzing and predicting carbon emissions27,28,29,30. These technologies enable the identification of patterns and trends in large datasets, offering valuable insights for decision-makers31,32,33. However, the accuracy and reliability of machine learning models depend on the quality of the data and the complexity of the models. Additionally, while ML models can identify key drivers of emissions34,35, they often fail to capture the dynamic, sector-specific nature of carbon emissions, limiting their ability to provide actionable guidance for targeted emission reduction efforts36.

Despite advancements in these areas, there remains a significant gap in the ability to provide comprehensive and dynamic guidance for pollution reduction efforts across sectors. Specifically, current models encounter difficulties in effectively correlating sectoral electricity consumption with carbon emissions and analyzing these relationships over time. The lack of models that integrate sector-specific and temporal factors in a dynamic framework leads to insufficient insights for developing targeted, industry-specific strategies.

This study aims to fill these gaps by constructing a dynamic correlation model between sectoral electricity consumption and the urban average CO2 column concentration (XCO2). By leveraging large-scale, multiperiod data from 16 cities (2017–2021) and employing advanced machine learning methods—such as random forest, extreme gradient boosting (XGBoost), and stacking regression—this high-precision model can be used to understand the dynamic relationship between electricity consumption and average XCO2. The model incorporates time-rolling window analysis techniques to dynamically identify the correlation between sector-specific electricity consumption with urban XCO2 over time. This dynamic approach provides actionable insights for policymakers and industry managers to refine emission reduction strategies. By offering sector-specific guidance, this study contributes to more effective pollution control measures, energy policy planning, and the achievement of carbon neutrality goals.

Large-scale, multiperiod collection of sectoral electricity consumption and carbon concentration data

Categorized data on total electricity consumption

In this study, categorized data on total electricity consumption were compiled across 16 cities from Jan. 2017 to Dec. 2021. The dataset is extensive and detailed, providing rich information that includes extensive and detailed information, covering various industries and sectors, and providing a wealth of information (see Table 1). These industries and sectors include traditional first industries such as agriculture, forestry, animal husbandry, and fishery, as well as resource-intensive industries such as coal mining, oil and natural gas extraction, and metal ore mining. Additionally, the dataset includes high-energy-consuming sectors in manufacturing, such as food processing, textiles, chemical products, metal smelting and rolling, machinery manufacturing, and electronic equipment manufacturing, along with energy supply industries such as electric power and heat production and supply. The dataset also comprehensively reflects electricity consumption in essential fields such as construction, transportation, and communication services, as well as public services and social services sectors such as water management, education, healthcare, and public administration. This comprehensive dataset supports research on the relationship between sectoral electricity consumption and average XCO2 in cities.

By thoroughly analyzing these electricity consumption data, this study aims to explore the dynamic temporal relationship between electricity consumption in various urban sectors and their average XCO2. This information will help us understand the impact of electricity consumption in different sectors on the overall carbon emissions of cities and provide a scientific basis for formulating effective carbon reduction strategies.

Average XCO2 data for urban areas

On the basis of the XGBoost machine learning algorithm, XCO2 data from multiple satellite sources (GOSAT, OCO-2, and OCO-3) were integrated and interpolated to reconstruct the monthly spatial‒temporal distribution of the 1 km grid XCO2 for the corresponding cities from 2017 to 2021 (see Fig. 1). For detailed information, see37.

Construction of a correlation model and Temporal correlation analysis between urban sectoral electricity consumption and average XCO2

To investigate the correlation between urban sector electricity consumption (such as residential, industrial, and service sector electricity consumption) and average XCO2, random forest, XGBoost, and stacking regression methods are employed to construct a correlation model. Furthermore, time rolling analysis techniques are introduced to reveal the dynamic temporal correlation between major sectoral electricity consumption and urban average XCO2.

Random forest model

Random forest is an ensemble learning method based on decision trees. It enhances accuracy and stability by generating multiple decision trees and averaging their predictions (for regression problems) or voting (for classification problems). This method applies “bagging” and random feature selection, allowing each tree to make high-variance, low-bias predictions, thereby reducing the risk of overfitting38.

A random forest consists of multiple decision trees, each trained with a subset of the training data. The model’s prediction is the average of all the trees’ predictions (for regression) or the majority vote (for classification). The formula is as follows:

where \(\hat {y}\) is the final prediction result of the random forest, N is the number of decision trees, and \({\hat {y}_i}\) is the prediction result of the i-th tree.

XGBoost model

XGBoost is an efficient implementation of gradient boosted decision trees (GBDTs), which are widely recognized for their advantages in handling large-scale data and achieving high accuracy. This model employs an incremental approach to optimize the loss function, where each newly added tree addresses the prediction errors from the previous trees, thereby enhancing the overall model performance39.

The XGBoost model iteratively improves its predictions by adding new trees. The goal of each new tree is to minimize the residuals (prediction errors) of all the preceding trees. The formula is as follows:

where \({\hat {y}^{(t)}}\) is the prediction result of the t-th round and \({f_t}(x)\) is the prediction result of the i-th tree. The optimization of the loss function is performed via the following formula:

where \({\text{ob}}{{\text{j}}^{(t)}}\) is the objective function of the t-th round, l is the loss function, Ω is the regularization term, and n is the number of samples.

Model fusion

To further enhance the predictive performance of the model, this study employs the stacking regressor method40, which fuses the random forest and XGBoost models. In the stacking regressor method, the input is the predictions of multiple base learners, and a new regressor is trained to output the final prediction.

where stacked_model is the correlation model. The estimators parameter specifies the set of base learners, including the best random forest model best_rf and the best XGBoost model best_xgb. The final_estimator is the final regressor; in this paper, ridge regression (RidgeCV) is selected as the final_estimator.

Temporal correlation analysis

This study employs time rolling analysis to examine the temporal variation in the correlation between electricity consumption by various urban sectors and average XCO2. Specifically, within each time window, the correlation between sectoral electricity consumption and average XCO2 is calculated, allowing for a dynamic examination of the potential impact of different sectors’ electricity consumption on changes in average XCO2 over different periods. This approach provides data and supports decision-making processes for formulating more effective carbon reduction strategies41.

(1) data window division

The data are divided into multiple fixed-size windows in chronological order, and the correlation for each window is calculated. Suppose that the time series data are given as \(D=({X_t},{y_t})_{{t=1}}^{T}\), where \({X_t}\) is the feature vector at time t and \({y_t}\) is the target variable at time t. If the size of the time rolling window is w, then the data for the k-th window are given as follows:

where i is the starting time index of the rolling window and w is the window size. In this study, each window contains data for 12 months.

(2) correlation calculation

where \({\text{importance}}{{\text{s}}_{{\text{window}}}}\) is the correlation within the window, M is the number of base learners, and \({\text{model}}.{\text{featur}}{{\text{e}}_{\text{i}}}{\text{mportance}}{{\text{s}}_{{\text{-j}}}}\) is the correlation of the j-th base learner.

For each time window, the corresponding feature matrix \({X_{{\text{window}}}}\) and target variable \({y_{{\text{window}}}}\) are extracted, and the correlation between electricity consumption by various urban sectors and the average XCO2 is calculated.

(3) time variation analysis of electricity consumption in the sector with the highest correlation

By employing the rolling window method, monthly variation in the correlation between electricity consumption by various urban sectors and the average XCO2 can be obtained. By selecting the sectors with the highest correlation each month, the trends over different periods are analyzed to better understand and reveal the potential correlation of electricity consumption in each sector with the average XCO2.

Assuming that the top k sectors are selected on the basis of their correlation, the correlations for these sectors within each time window are represented as:

By using time series analysis methods, the trend of these correlation values can be plotted over time:

where \(importance\_trend(t)\) represents the correlation between electricity consumption in the top k sectors and the average XCO2 at time t.

Model training and parameter configuration

Model training and performance evaluation

The training process for modeling the relationship between urban sectoral electricity consumption and average XCO2 involves two steps: first, the base learners (random forest and XGBoost) are trained, and then, the outputs of these base learners are used as new features to train the final regressor (ridge regression). The specific steps are as follows:

(1) Base learner training: Cross-validation is performed with the training data to obtain the predictions of each base learner.

(2) Final regressor training: The predictions of the base learners are used as input features to train the final regressor.

In this model, \({\hat {y}_{{\text{stacked}}}}\) is the final prediction result, and \({\hat {y}_{i,{\text{rf}}}}\) and \({\hat {y}_{i,{\text{xgb}}}}\) are the predictions of the random forest and XGBoost base learners, respectively. The model performance is evaluated via the coefficient of determination (\({R^2}\)) and the root mean square error (RMSE)42:

where \({y_i}\) is the true value, \({\hat {y}_i}\) is the predicted value, \(\bar {y}\) is the mean of the true values, and n is the number of samples.

Model parameter configuration

(1) The main hyperparameters of the random forest algorithm include the following:

-

n_estimators: The number of decision trees constructed in the random forest. Increasing the number of trees can enhance model performance but increases computational costs.

-

max_depth: Controls the maximum depth of the tree. When set to None, the trees grow until all leaf nodes are pure or contain fewer samples than min_samples_split does.

-

min_samples_split: The minimum number of samples required to split an internal node. Larger values can prevent the model from overfitting.

-

min_samples_leaf: The minimum number of samples required to be at a leaf node. Larger values can prevent the model from learning noise in the training data.

Hyperparameter tuning is performed via RandomizedSearchCV43. The specific settings for the hyperparameter search space are shown in Table 2.

(2) The main hyperparameters of XGBoost include the following:

-

n_estimators: The number of boosting trees. Increasing the number of trees can improve model performance but also increase training time.

-

max_depth: Controls the maximum depth of the tree. Greater depth could lead to overfitting, whereas shallower depth could cause underfitting.

-

learning_rate: Controls the learning rate for each boosting step. A smaller learning rate makes the model more robust but requires more boosting trees.

-

Subsample: The proportion of samples used to train each tree. The values range from (0, 1], which helps prevent overfitting.

-

colsample_bytree: The proportion of features used to construct each tree. The values range from (0, 1], which helps prevent overfitting.

Hyperparameter tuning is performed via RandomizedSearchCV. The specific settings for the hyperparameter search space are shown in Table 3.

By tuning these hyperparameters, one can find the optimal model configuration and improve the model’s predictive performance.

Experiment analysis

Performance validation of the correlation model in different cities

The predictive performance of the correlation model varies across different cities (see Table 4), generally yielding favorable results. In several cities, such as City 1, City 2, City 3, and City 4, the model achieves high R2 values of 0.864, 0.8528, 0.8327, and 0.8325, respectively, indicating strong explanatory power for the relationship between electricity consumption and carbon concentration. Additionally, the model achieves low RMSE values for these cities, recorded at 1.3502, 1.4939, 1.5082, and 1.6058, respectively, reflecting smaller prediction errors.

For other cities, such as City 5 and City 6, the model performance is somewhat low, with R2 values of 0.7846 and 0.8301 and RMSE values of 1.8904 and 1.6032, respectively. This finding suggests a more complex relationship between electricity consumption and carbon concentration in these cities, possibly due to data noise or additional influencing factors. Additional model optimization or the introduction of additional features may be needed to improve predictions in these areas.

In addition, a comparative analysis is conducted with widely used models such as random forest and XGBoost, with a focus on key metrics such as R2 and RMSE across multiple cities (see Table 4). Our model consistently outperforms or matches the benchmark models, achieving higher R2 values and lower RMSE scores in most cases. For example, in City 1, our model achieves an R2 of 0.864 and an RMSE of 1.3502, outperforming random forest (R2 = 0.8071, RMSE = 1.608) and XGBoost (R2 = 0.862, RMSE = 1.3603). These results underscore the advanced capabilities of our approach in providing accurate and reliable predictions.

The correlation model demonstrates robust performance in predicting the relationship between electricity consumption and average XCO2 across most cities, thereby validating its effectiveness and reliability. This model comparison further emphasizes the advantages of the proposed model, providing a solid foundation for further investigations into the temporal dynamics between sectoral electricity consumption and the urban carbon concentration.

Performance analysis of the correlation model for predicting average XCO2 in various cities

This study presents a comparison of the actual and model-predicted average XCO2 values across sixteen cities (Cities 1–16), as shown in Fig. 2. The predicted values (red lines) closely align with the actual values (blue lines) across most periods, indicating that the model can effectively capture the relationship between sectoral electricity consumption and average XCO2 in each city.

In terms of city-specific performance, the model generally captures the trend accurately across all cities. For City 1 (Fig. 2a), the model effectively follows the trend in average XCO2, with only minor deviations in short-term fluctuations. For City 2 (Fig. 2b), the model provides accurate predictions of peaks and troughs in 2019 and 2020, although its performance is slightly reduced during more volatile periods. For City 3 (Fig. 2c), long-term trends are well captured, despite slight discrepancies in short-term variations, whereas, for City 4 (Fig. 2d), the model achieves high accuracy, especially in 2020 and 2021, reflecting its strong predictive ability. For City 5 (Fig. 2e), the model shows minor deviations during peak periods but performs well overall. For City 6 (Fig. 2f), the overall trend is captured effectively, with minor inaccuracies during low-activity periods. Among the extended cities (Cities 7–16 (Fig. 2g–p)), the model values closely align with actual values in most cases, particularly in Cities 7, 8, 9, 13, 14, 15, and 16. For Cities 10, 11, and 12, while the model performs well overall, there are occasional slight discrepancies during more volatile periods.

Overall, the analysis across 16 cities confirms the model’s ability to mine the relationship between electricity consumption and average XCO2. Although there are minor shortcomings in predictions for certain periods and cities, the model consistently demonstrates effectiveness and reliability.

Temporal correlation analysis between sectoral electricity consumption and average XCO2 in cities

To thoroughly analyze the temporal variation in the correlation between electricity consumption by various sectors and the average XCO2 in cities, this study employs a time rolling analysis method to calculate the potential correlation of electricity consumption in different sectors with changes in average XCO2 over different periods. This section highlights the temporal trends of the top three electricity-consuming sectors in each city, as shown in Fig. 3. The detailed findings are as follows.

The correlation between electricity consumption and average XCO2 in City 1 clearly exhibited seasonal fluctuations, particularly between 2019 and 2020. In Mar. 2019, the highest correlation, 0.438, was observed between electricity consumption in manufacturing (label 13) and average XCO2. In contrast, in Dec. 2019, the building sector (label 45) had the greatest impact on average XCO2, with a correlation of 0.486, suggesting that winter construction activities may increase carbon emissions. In Jun. 2020, for the transportation sector (label 51), a significant increase in correlation of 0.462 was observed, reflecting the impact of the heavy-traffic season on the electricity consumption‒carbon emission relationship. In City 2, the highest correlation between the building sector (label 45) and average XCO2 of 0.458 occurred in Dec. 2018. In Aug. 2020, the agriculture sector (label 1) peaked at a correlation of 0.412, indicating that summer agricultural activities significantly influence energy demand and carbon emissions. In Jan. 2021, the water supply sector (label 44) exhibited a strong correlation of 0.419. These patterns reveal distinct seasonal differences in energy demand and carbon emissions in City 2. City 3 showed significant correlations in the chemical industry (label 25), with a peak of 0.437 in May 2019 and a similar trend in July 2020 (0.424). The transportation sector (label 51) in Nov. 2020 also showed a notable correlation of 0.421. Overall, the relationship between electricity consumption and average XCO2 in City 3 is complex, with seasonal variations driven by different industries.

In City 4, a prominent correlation of 0.479 was observed in Sept. 2019 between the transportation sector (label 51) and average XCO2. In winter 2020, the building sector (label 45) exhibited a high correlation, peaking at 0.463 in Dec. Agriculture (label 1), also showed a strong correlation in Aug. 2020, with a peak of 0.444, reflecting the significant seasonal impacts of various industries. City 5 displayed similar seasonal fluctuations. In Oct. 2019, the water supply sector (label 44) had a strong impact, with a correlation of 0.473, whereas in the summer of 2020, the transportation sector (label 51) had an increased correlation of 0.428. In Dec. 2020, the building sector (label 45) once again demonstrated a strong seasonal correlation of 0.391. In City 6, the relationship between electricity consumption and average XCO2 also exhibited seasonal fluctuations. In Feb. 2019, agriculture (label 1) had a high correlation of 0.485, reflecting the seasonal impact of agricultural production on carbon emissions. In May 2020, both the building sector (label 45) and the chemical industry (label 25) showed significant correlations, with values of 0.457 and 0.424, respectively. The transportation sector (label 51) in autumn 2020 also demonstrated a strong correlation.

City 7’s electricity consumption and average XCO2 correlation peaked in Dec. 2019, especially in the building sector (label 45), which had a correlation of 0.492. In spring 2020, agriculture (Label 1) showed a correlation of 0.448, highlighting the impact of the busy agricultural season on carbon emissions. In Jan. 2021, the water supply (label 44) and transportation (label 51) sectors exhibited correlations of 0.421 and 0.419, respectively. In City 8, the chemical industry (label 25) showed a significant correlation with the average XCO2 in Apr. 2019, with a value of 0.472. In summer 2020, the transportation sector (label 51) had a correlation of 0.429, whereas agriculture (label 1) had a notable correlation of 0.436 in autumn 2020, indicating the seasonal contribution of agricultural activities to carbon emissions. In City 9, the building sector (label 45) had a correlation of 0.464 with the average XCO2 in the winter 2020. The transportation sector (label 51) had a correlation of 0.428 in autumn, whereas agriculture (label 1) had a significant correlation of 0.469 in spring 2019. Overall, the electricity consumption‒average XCO2 relationship in City 9 is influenced by multiple factors, particularly transportation and construction.

In City 10, the transportation sector (label 51) had a correlation of 0.476 in summer 2019, whereas the building sector (label 45) peaked at 0.491 in autumn 2020, illustrating the seasonal impact on carbon emission patterns. Agriculture (label 1) had a correlation of 0.424 in spring 2021. In City 11, the building sector (label 45) exhibited a correlation of 0.459 with electricity consumption in Oct. 2019. In summer 2020, the transportation sector (label 51) had a significant impact, with a correlation of 0.445. Other sectors, such as agriculture (label 1) and water supply (label 44), also showed strong correlations in different seasons. City 12’s correlation between electricity consumption and average XCO2 demonstrated clear seasonal fluctuations. In Dec. 2019, the building sector (label 45) had a correlation of 0.474. In the summer of 2020, agriculture (Label 1) reached a correlation of 0.487, whereas the transportation sector (Label 51) showed a correlation of 0.419 in autumn, highlighting the interaction between different sectors and seasons.

In City 13, the chemical industry (label 25) had a correlation of 0.468 in April 2019. In winter 2020, the building sector (label 45) exhibited a high correlation of 0.482, reflecting the impact of winter construction activities on carbon emissions. Agriculture (Label 1) also showed a significant correlation of 0.461 in summer 2020. In City 14, electricity consumption and average XCO2 correlations showed clear seasonal fluctuations. In Feb. 2019, transportation (label 51) and water supply (label 44) had significant correlations of 0.468 and 0.403, respectively. The building sector (label 45) peaked at a correlation of 0.392 in Dec. 2020, suggesting that winter heating and construction activities intensified carbon emissions. Agriculture (Label 1) had a high correlation of 0.478 in Aug. 2018, indicating the substantial impact of agricultural activities on average XCO2. City 15 exhibited volatile correlations between electricity consumption and average XCO2. In July 2019, the chemical industry (label 25) showed a strong correlation of 0.442. In February 2021, manufacturing (label 13) had a correlation of 0.419. In May 2020, the transportation sector (label 51) demonstrated a significant correlation of 0.377, emphasizing the sector’s impact on average XCO2. Overall, the relationship in City 15 was influenced by both seasonal changes and industry fluctuations, particularly with respect to chemicals and transportation. In City 16, the correlation between electricity consumption and average XCO2 followed a similar seasonal pattern to that of other cities. In Sep. 2020, the transportation sector (label 51) had the highest correlation at 0.492. In Nov. 2019, the building sector (label 45) showed a notable correlation of 0.479. Other sectors, such as agriculture (Label 1) and food manufacturing (Label 13), displayed strong correlations at different times, with agriculture reaching 0.463 in May 2019 and food manufacturing 0.410 in Jan. 2021.

The analysis of the 16 cities revealed significant seasonal fluctuations in the relationship between electricity consumption and average XCO2, with different industries playing key roles. Notably, the building, agriculture, and transportation sectors have the greatest impacts on this relationship, especially in winter and summer. The seasonal fluctuations, changes in energy demand, and periodic economic activities all contribute to the complex interactions that shape carbon emission patterns.

Conclusions

The significant contributions of this study are reflected in the development of a correlation model that links sectoral electricity consumption with urban average XCO2, providing a detailed analysis of the correlation between electricity consumption and carbon emissions. XCO2 data and comprehensive electricity consumption data from 16 cities spanning from Jan. 2017 to Dec. 2021 were collected. These datasets include electricity use across various sectors, serving as the foundation for building and refining the model. The correlation model was constructed via advanced machine learning techniques—specifically, random forest, XGBoost, and stacking regression—and its performance was evaluated via metrics such as R2 and RMSE. The results demonstrated that the model effectively captured the relationship between electricity consumption and carbon concentration, with high predictive accuracy and low error rate. The best performance was observed with an R2 of 0.8564 and an RMSE of 1.350. The model’s reliability was validated by comparing its predictions with actual average XCO2 across 16 cities, as the predicted values were closely aligned with the observed data for most periods.

In addition, the dynamic relationship between electricity consumption and carbon emissions was explored via a rolling window method to calculate correlations between electricity consumption in different sectors and changes in average XCO2 over time. The findings revealed that this relationship is not static but varies over time, with some sectors showing stronger correlations at specific points. Overall, this study provides a scientific basis for understanding the role of sectoral electricity consumption in shaping urban carbon emissions. The insights generated offer valuable guidance for policymakers and industry managers to develop more targeted and effective pollution reduction and carbon mitigation strategies, ultimately contributing to more sustainable urban development and the realization of global carbon neutrality goals.

In future studies, the model could be refined and expanded by incorporating additional variables, such as meteorological data and socioeconomic factors, to improve its predictive accuracy and robustness. In addition, future research will aim to integrate cross-national data and expand the analysis to other cities and regions for broader comparisons, further validating the model’s generalizability and addressing challenges in data collection and integration, thereby providing a wider understanding of global carbon dynamics and supporting sustainable urban planning and the global transition toward carbon neutrality.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Upadhyay, R. K. Markers for global climate change and its impact on social, biological and ecological systems: A review. Am. J. Clim. Change 9, 159 (2020).

Rajak, J. A preliminary review on impact of climate change and our environment with reference to global warming. Int. J. Environ. Sci. 10, 11–14 (2021).

Jogdand, O. K. Study on the effect of global warming and greenhouse gases on environmental system. In Green Chemistry and Sustainable Technology, 275–306 (Apple Academic Press, 2020).

Chen, L. et al. Strategies to achieve a carbon neutral society: a review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 20, 2277–2310 (2022).

Liu, Z. et al. Challenges and opportunities for carbon neutrality in China. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 3, 141–155 (2022).

De La Peña, L., Guo, R., Cao, X., Ni, X. & Zhang, W. Accelerating the energy transition to achieve carbon neutrality. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 177, 105957 (2022).

Nikolaidou, A., Kopsacheilis, A., Gavanas, N. & Politis, I. The dynamic relation of climate change and energy transition with transport and mobility policies in the EU through social media data mining. In Conference on Sustainable Urban Mobility 17–28 (Springer).

Szramowiat-Sala, K. et al. AI-based data mining approach to control the environmental impact of conventional energy technologies. J. Clean. Prod. 472, 143473 (2024).

Huisingh, D., Zhang, Z., Moore, J. C., Qiao, Q. & Li, Q. Recent advances in carbon emissions reduction: policies, technologies, monitoring, assessment and modeling. J. Clean. Prod. 103, 1–12 (2015).

Dai, J., Farooq, U. & Alam, M. M. Navigating energy policy uncertainty: effects on fossil fuel and renewable energy consumption in G7 economies. Int. J. Green. Energy, 1–14 (2024).

Chen, Y. et al. Substantial differences in source contributions to carbon emissions and health damage necessitate balanced synergistic control plans in China. Nat. Commun. 15, 5880 (2024).

Kuang, Y., Fan, Y., Bin, J. & Fan, M. Impact of the digital economy on carbon dioxide emissions in resource-based cities. Sci. Rep. 14, 16514 (2024).

Ibekwe, K. I. et al. Energy efficiency in industrial sectors: A review of technologies and policy measures. Eng. Sci. Technol. J. 5, 169–184 (2024).

Eldering, A. et al. The orbiting carbon Observatory-2 early science investigations of regional carbon dioxide fluxes. Science 358, eaam5745 (2017).

Wiedmann, T. et al. Three-scope carbon emission inventories of global cities. J. Ind. Ecol. 25, 735–750 (2021).

Wang, J. et al. Large Chinese land carbon sink estimated from atmospheric carbon dioxide data. Nature 586, 720–723 (2020).

Li, J. et al. High-spatiotemporal resolution mapping of spatiotemporally continuous atmospheric CO2 concentrations over the global continent. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 108, 102743 (2022).

He, C., Ji, M., Grieneisen, M. L. & Zhan, Y. A review of datasets and methods for deriving Spatiotemporal distributions of atmospheric CO2. J. Environ. Manag. 322, 116101 (2022).

Zhang, J., Liu, L., Xie, Y., Zhang, Y. & Guo, H. An integrated optimization and multi-scale input–output model for interaction mechanism analysis of energy–economic–environmental policy in a typical fossil-energy-dependent region. Energy Strategy Rev. 44, 100947 (2022).

Zhao, S., Shi, Y. & Xu, J. Carbon emissions quota allocation based equilibrium strategy toward carbon reduction and economic benefits in China’s Building materials industry. J. Clean. Prod. 189, 307–325 (2018).

Verma, P., Kumari, T. & Raghubanshi, A. S. Energy emissions, consumption and impact of urban households: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 147, 111210 (2021).

Liu, X. et al. Scenario simulation of urban energy-related CO2 emissions by coupling the socioeconomic factors and Spatial structures. Appl. Energy 238, 1163–1178 (2019).

Doğan, B., Driha, O. M., Lorente, B., Shahzad, U. & D. & The mitigating effects of economic complexity and renewable energy on carbon emissions in developed countries. Sustain. Dev. 29, 1–12 (2021).

Ou, J., Liu, X., Li, X. & Chen, Y. Quantifying the relationship between urban forms and carbon emissions using panel data analysis. Landsc. Ecol. 28, 1889–1907 (2013).

Bekhet, H. A., Matar, A. & Yasmin, T. CO2 emissions, energy consumption, economic growth, and financial development in GCC countries: dynamic simultaneous equation models. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 70, 117–132 (2017).

Luo, J., Zhuo, W., Liu, S. & Xu, B. The optimization of carbon emission prediction in low carbon energy economy under big data. IEEE Access. (2024).

Farahzadi, L. & Kioumarsi, M. Application of machine learning initiatives and intelligent perspectives for CO2 emissions reduction in construction. J. Clean. Prod. 384, 135504 (2023).

Gaur, L., Afaq, A., Arora, G. K. & Khan, N. Artificial intelligence for carbon emissions using system of systems theory. Ecol. Inf. 76, 102165 (2023).

Akyol, M. & Uçar, E. Carbon footprint forecasting using time series data mining methods: the case of Turkey. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. 28, 38552–38562 (2021).

Dinçer, H. et al. Integrating data mining and fuzzy decision-making techniques for analyzing the key minimizing factors of carbon emissions. J. Intell. Fuzzy Syst., 1–17 (2023).

Abuzir, S. & Abuzir, Y. Data mining for CO2 emissions prediction in Italy. Mühendislik Bilimleri Ve Araştırmaları Dergisi. 3, 59–68 (2021).

Pan, W., Miao, L. & Lin, Z. Analysis of enterprise data-driven innovation diffusion supervision system based on the perspective of green supply chain. J. Org. End. User Comput. (JOEUC). 35, 1–28 (2023).

Wang, G., Zhang, X., Gao, Y., Yee, A. L. & Wang, X. The use of an internet of things data management system using data mining association algorithm in an e-commerce platform. J. Org. End. User Comput. (JOEUC). 35, 1–19 (2023).

Yang, L., Tian, X., Zhao, X. & Wang, L. Low-carbon optimization in commercial buildings through data mining. In E3S Web of Conferences. 01016 (EDP Sciences).

Willetts, M. & Atkins, A. S. Application of data mining to support facilities management in smart buildings. In IoT Enabled Computer-Aided Systems for Smart Buildings, 121–143 (Springer, (2023).

Bengio, Y., Goodfellow, I. & Courville, A. Deep Learning Vol. 1 (MIT Press, 2017).

He, C. et al. Deriving full-coverage and fine‐scale XCO2 across China based on OCO‐2 satellite retrievals and carbontracker output. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2022GL098435 (2022).

Rigatti, S. J. Random forest. J. Insur. Med. 47, 31–39 (2017).

Chen, T., Guestrin, C. & Xgboost A scalable tree boosting system. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining. 785–794.

Acharya, S. et al. Non-invasive estimation of hemoglobin using a multi-model stacking regressor. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inf. 24, 1717–1726 (2019).

Kish, L. Space/time variations and rolling samples. J. Off. Stat. 14, 31 (1998).

Alpaydin, E. Machine Learning (MIT Press, 2021).

Vishnu, M. et al. Recurrent gastric cancer prediction using randomized search cv optimizer. In 2023 International Conference on Computer Communication and Informatics (ICCCI) 1–5 (IEEE, 2023).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the Science and Technology Project of State Grid Corporation of China (No. 1400–202426279 A-1-1-ZH).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Yufei Teng: As the lead author, responsible for research design and data analysis, ensuring the scientific accuracy of the methods.Han Zhang: Assisted in data collection and processing, participated in model construction, and provided valuable insights for the results discussion.Yu Zhan: As the corresponding author, guided the overall research direction, responsible for writing and editing the paper to accurately convey the findings.Zhengwei Chang: Contributed to the literature review and background research, providing theoretical support for the study and assisting in data analysis.Yumin Chen: Responsible for data visualization, ensuring the research results are presented clearly and enhancing the paper’s readability.Xinyi Liu: Participated in model validation and result interpretation, ensuring the reliability of the research conclusions.Hongli Liu: Provided expertise in statistical analysis, helping to optimize the analysis methods and offering suggestions for the research design.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Teng, Y., Zhang, H., Zhan, Y. et al. Dynamic correlation analysis of sectoral electricity consumption and urban carbon concentration using machine learning models. Sci Rep 15, 9939 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-94201-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-94201-z