Abstract

Tourism activities are changing the global landscape pattern. This study attempted to estimate changes in Land Use Land Cover (LULC) and Land Surface Temperature (LST) in District Buner and Shangla, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KPK), Pakistan, and specifically its tourist spots. Using remote sensing data from satellites (1990–2020) and future projections (2035–2050), we applied Artificial Neural Network (ANN) and Cellular Automata Markov (CA-Markov) models to examine past and future LULC and LST dynamics across two districts including four major tourist spots (Shangla Top as tourist spot one (TS1), Bar Puran (TS2), Shahida Sar (TS3), and Daggar (TS4). The LULC classification for the whole study area (1990–2020) indicates that built-up and agricultural areas increased with a net change of +0.8% and +3.2% for the Shangla and Buner districts, respectively. The highest mean LST was found in the built-up areas. The simulation results indicate an expansion of 4.5% and 5.8% of the total built-up areas, and the LST above 31 °C will cover 76% and 88% of the total areas in 2035 and 2050, respectively. This conversion is driven by tourism activities, causing urban heat island effects (UHIs), and environmental degradation. The analysis of tourist spots (1990–2020) shows the highest change in built-up areas at Shangla Top (TS1), while the highest LST (28 °C) for the Daggar (TS4). The future simulation (2035–2050) results for tourist spots show that TS4 would have the highest LULC change in built-up areas (5.67%), and TS4 would have the highest LST (31 °C) from 65.23 to 82.20%. These findings provide an essential understandings for developing long-term tourism policies meant to moderate the environmental impact of tourism in the region.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Anthropogenic activities have influenced the global climate system, affecting Land Use Land Cover (LULC) worldwide1,2,3. Over the previous six decades, about one-third (32%) of the world’s land area has changed due to human activities, which are different in the south and north of the globe4,5. Tourism is one of the world’s largest sectors, employing every eleventh person, contributing 9% of global Gross domestic product (GDP), and accounting for 6% of all exports in 20146,7. Tourists’ activities induce changes in the area, particularly LULC and Land Surface Temperature (LST)8.Tourism infrastructure, vacation houses, golf courses, shopping centers, and highways are tied directly to the LULC changes9,10,11. As a result of the world’s booming tourism industry, land fragmentation has increased with various socio-environmental impacts12,13. Even though LULC’s changing aspects are vital in tourism, it is hard to measure and calculate them due to the unavailability of micro-level geo-referenced data sets, the vast number of possible assumptions, and the difficulty in tracking tourism-associated activities that deliver public services to tourists and the local inhabitants10,14.

LST is one of the most important environmental research parameters, including ocean circulation, climate change, and weather forecasting15. Urban areas have a higher LST, which forms Urban Heat Islands (UHIs), resulting in several health and environmental effects, such as heatstroke and urban warming16,17. Because of impervious surfaces, LST varies spatially and temporally and has a significant temperature difference between urban and surrounding areas18. Given the spatial consequences of tourist development, it’s not surprising that researchers are looking into its effects on LULC and LST. However, few empirical studies based on micro-level datasets were conducted, which show a relationship between LULC, LST, and tourism19,20. The landscape maps used in LULC and LST research are dependent on remote sensing data gathered at an insufficient time and spatial scale21. Besides, LULC and LST directly caused by tourism are difficult to trace22. Direct effects of tourism development on LULC and LST, such as land conversion and UHIs for the construction of Thermal Anomaly Extraction (TAE), are often challenging to link tourism development and landscape changes without thorough fieldwork. However, most of the research used Geographic Information System (GIS) and Remote Sensing (RS) methods to investigate the effects of tourism development on LULC without doing field surveys23,24,25.

Since 2013, Pakistan has experienced significant tourism development in its Northern Areas, leading to LULC and LST changes. Shangla and Buner Districts in the KPK province of Northern Pakistan are attractive tourist destinations for local and international tourists because of their topography, climate and diverse flora. Consequently, the rapid expansion of the population and built-up areas occurred due to business opportunities, and it has impacted the LULC and LST in the study area. However, no specific investigation has been conducted on the association between tourism development, LULC, and LST in this study area. Therefore, the current study explores the impacts of tourism on LULC and LST changes using remote sensing data over the past 30 years and their prediction using Cellular Automata Markov (CA-Markov) and Artificial Neural Network (ANN) models in the District Buner and Shangla of KPK, Pakistan. This study may help to understand social and environmental factors and policymaking for sustainable tourism management.

Materials and methods

Study area

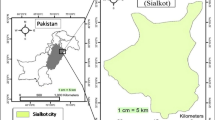

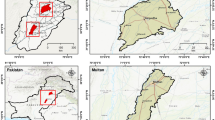

The districts Buner and Shangla are in Northern Pakistan (KPK province) at 33°45′ to 34°30′ N and 73° to 73°30′ E (Fig. 1). The total population of the study area is 1.2 million, and it occupies an area of 2800 km2. Between 1998 and 2020, the population grew from 0.7 to 1.2 million, with growth rates of 4.3% and 2.5% in urban and rural areas, respectively26. The average annual temperature of the area is 18°C27, with June being the warmest (28.1 °C) and January being the coldest (7.5 °C) month of the year. The region is located in the lower Himalayas, which are Pakistan’s most popular tourist destinations, including the western Himalayas and the Karakoram28,29. Districts Buner and Shangla consist of beautiful valleys between hillocks and high mountains covered with dense forests comprised of Pindrow Fir, Morinda Spruce, Blue Pine (Kail), Chir Pine, and Deodar trees. The average elevation ranges from 2000 to 3000 m above sea level30. The highest point (3,440 m) is near Kuz Ganrshal in the northwestern corner of the study area.

The selected tourist spots are declared as tourist spots in the respective Districts by the government of KPK province through the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Board of Investment and Trade (KPK BOIT)20. Additionally, these spot’s characteristics were environmental sensitivity, tourist frequency, diversity, accessibility, and their pleasant climate. Among them, Shangla Top—as Tourist Spot One (TS1, with an area of 75.66 km2) and Bar Puran (TS2, with an area of 39.01 km2) are the main tourist sites in Shangla District, while Shahida Sar (TS3, with an area of 52 km2), and Daggar (TS4, with an area of 56 km2) are in the Buner District. The TS1 and TS2 are famous for their natural green meadows, pines forests, varieties of wild animals and snow-covered mountains. At the same time, the TS3 is famed for the mountainous terrain where the local government has developed tourist residing areas and the TS4 is well-known for the “Peer Baba Graveyard” having religious significance. Thousands of tourists visit31 the said locations, where the local communities rely on the tourism sector for their incomes21.

Data sets

Landsat images (Landsat 5-TM and Landsat 8-OLI) were downloaded (for the years 1990, 2005, and 2020) for May to minimize the seasonal variation, where an overall cloud cover of less than 15% was selected (Table 1). The obtained data was geo-referenced with the WGS-84 projection system using Arc-Map 10.5. Before LULC classification, the data was processed including atmospheric correction, line removal, and mosaicking. During field visits, forty ground truth locations were selected for each LULC class to verify the correctness of classified LULC maps (Fig. 2). Driving variables were gathered from the United Geological Survey (USGS) website and the local municipality, including the Digital Elevation Model (DEM) with a resolution of 30 m and the road shapefile was utilized in LULC projections.

Estimation of LULC changes for the period 1990 to 2020

RGB images were classified using the standard supervised classification method for LULC estimation. The land classes were categorized into built-up, bare soil, vegetation, agriculture, and water bodies for the years 1990‒2020, using the ANN classification method32. The agriculture and vegetation classes were differentiated as, the raising of food and plants with the help of humans—agriculture; and plants and trees that grow naturally without human intervention—vegetation32. To validate the accuracy of LULC classification, we utilized training samples (72%) and testing samples (28%), and the confusion matrix approach was used employing the kappa coefficient and overall accuracy values33. Additionally, we used shapefiles for each sample, rather than points to enhance the precision of validation samples. LULC classification accuracy was greater than 80% for each of the three classified images. Ground-truth points were generated using aerial imagery, Google Earth pictures, topography maps, and GPS points taken during fieldwork to evaluate the accuracy of categorization. Training samples were overlaid on Google Earth Engine (GEE) with the help of Environment for Visualizing Images (ENVI) 5.3 software to enhance the accuracy of training samples for each land cover class. They were examined through post-classification34 modifications from 1990 to 2020. The overall accuracy was calculated by dividing the cumulative number of correctly identified pixels by the cumulative number of total pixels35,36. The confusion matrix yielded four distinct matrices, i.e., user accuracy, producer accuracy, overall accuracy, and kappa coefficient.

LST trends from 1990 to 2020

The thermal data of the Landsat satellite stored as digital numbers (DN) was converted into LST using the four key steps37,38. Using the minimum (LMIN) and maximum wavelength (LMAX) data from Landsat metadata files, DN was transformed into spectral radiance (Eq. 1). The Landsat information files were acquired from the USGS web site together with the Landsat images.

Equation 2 was used to convert the spectral radiation into brightness temperature (BT).

K1 and K2 represent Calibration Constants 1 and 2. For Landsat 5 and Landsat 7, the values of K1 and K2 (obtained from Landsat metadata files) were 607.76, 1260.56, 666.09, and 1282.71, respectively. Landsat 8 (band 10 and 11), K1 and K2 values were 774.89 and 1321.08, 480.88 and 1201.14, respectively. BT was transformed using the usual conversion equation (Eq. 3) from Kelvin to degrees Celsius.

where: λ = represented the wavelength of emitted radiance, the peak response and the average of the limiting wavelengths (λ = 11.5 μm); ρ = h ∗ c/σ (1.438 × 102 mK). c = velocity of light (2.998 ∗ 108 m/s), σ = Boltzmann constant (1.380 649 ∗10–23 J/K), h = Planck’s constant (6.626 ∗ 10–34 J s). ε = Surface emissivity.

In addition, the wavelengths of surface emissivity and emitted radiance, denoted by λ and ε, respectively, are the peak response and the average of the limiting wavelengths (λ = 11.5 μg). PV (Proportion of vegetation) was used to calculate surface emissivity, which is derived from the NDVI of the years 1990, 2005, and 2020. The following formulae39, are used to calculate the PV:

At the end, the surface emissivity was determined by employing equation (Eq. 6)39:

The PV is the perpendicular vegetation index calculated from NDVI.

Standardization of LST

Standardization of LST was carried out to ensure comparability, as the topographic and seasonal differences are associated with mountainous regions in the thermal pictures of various Landsat data years. A number of gross approaches were utilized to eliminate the cloud-contaminated pixels, and Eq. 7 was utilized to standardize the LST40.

where LSTs = Standardized Land Surface Temperature, LSTu = Mean predicted Land Surface Temperature (1990–2020), LSTΩ = Standard deviation of Land Surface Temperature (1990–2020).

LST classification

LST was categorized into five classes (< 12 °C, 12 °C to < 16 °C, 16 to < 22 °C, 22 to < 28, and > 28 °C) to assess the detailed variations41 (1990–2020) (Fig. 3).

Simulating land cover projections maps for 2035 and 2050

Through the utilization of the MOLUSCE tool in Quantum Geographic Information System (QGIS), a CA–Markov model was utilized to forecast future LULC changes42,43. Two categories of variables were used to make the prediction: the dependent variables—including the historical LULC changes from 2005 to 2020, and the independent variables including the distance to elevation, highways, and slope. This computed the distance to roads using the Euclidean distance function in ArcMap. The variables so produced have been used to come up with the transition potential matrix, which assists in forecasting how land cover will be over time. This research applied the technique of random sampling with maximum iterations of 1000 and a neighborhood pixel size that was a 3 × 3 cell area. A CA model is utilized, modeled the transition potential matrix by applying logistic regression to simulate LULC maps for 2035 and 2050. The reliability of the model can be ensured with the support of existing datasets, in which we validate our results. We cross-compared the actual year’s LULC projected by the map of the year 2020 against the actual data that is in line with the corresponding year’s Landsat data. In order to evaluate the model’s accuracy, we generated several Kappa (K) parameters from the validate module of the IDRISI Taiga software: K-no, K-location, and K-standard. To determine the kappa coefficients and percentage correctness in the overall kappa between the categorised and forecasted LULC map of 2020, the QGIS-MULUSCE module was used. These validation steps confirmed the accuracy of the CA–Markov model before it was applied to future projections.

Simulating LST projections for 2035 and 2050

We examined past patterns in LST and used them to simulate, model, and predict future variations using a multi-layer feed-forward reverse propagation ANN technique in MATLAB software44,45. Parameters are automatically determined using the Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) neural network, which learns from errors to improve performance. The LST simulation in this study was prepared using patterns in LST data from 1990 to 2020. Using QGIS, the research region was partitioned into 500 × 500 m grids to generate sample points of geographically related units. A MATLAB Neural Network was trained using the sample data to forecast LST. As the results of the model improved upon including more input parameters, we expanded the model to include the areal extent values of the geographic sample units expressed in latitude and longitude. In this regard, Mean Squared Error (MSE) and correlation coefficient (R) values were used to assess confidence in the network. The value of R was 0.8, and MSE was 0.5. The Graphical User Interface (GUI) was created to verify the performance indication before implementing the network. We saved the network’s performance indicators for prediction once they were satisfactory. After numerous experiments with different values of MSE and R, we settled on several hidden layers. After testing various configurations, we used three hidden layers for this study. We assumed an initial learning rate (μ) of 0.1 and a delay rate of 0.9 for β to optimize predictions. This setup assisted by ensuring the reliability of the LST projection for the years 2035 and 2050.

LULC and LST changes in tourist spots

To evaluate the historical and future changes of LULC and LST in the tourist areas, these areas were extracted from the past and future LULC and LST maps of the whole study area with the help of the ArcMap 10.5 application. After extraction, LULC and LST changes were studied for 1990–2020 and future projections analysis for 2035 and 2050). For determining the mean LST changes, samples were chosen using QGIS 2.8 software from each site map28.

Results

Past pattern of LULC changes in the study area and selected tourist spots

The past patterns of LULC classes in the tourist spots and the entire study area for 1990, 2005, and 2020 are shown in Figs. 4 and 5, as well as Tables 3 and 4. For all three LULC classified images of the entire study area, the ANN’s overall classification accuracy was above 80% (Table 2). These categories included built-up areas, bare soil, vegetation, agriculture, and water bodies. All the classes showed an increasing trend except for the vegetation class which declined by − 140.6 km2 (− 5%). The increase in the built-up area and agriculture was from 100.4 to 123.7 km2 and 661.1 to 751 km2 respectively (years 1990–2020), while in case of bare soil, initially it decreased from 1990 to 2005 by − 53.9 km2 and then increased from 2005 to 2020 (Table 3 and Fig. 4).

When we compared past LULC changes in the entire study area (Table 3), the tourist spots had high net changes (Table 4). In the tourist spots TS1, TS2, TS3, and TS4 the changes in the built-up area in TS2 (2.6%, 1.4 km2) and TS4 (2.8%, 1.1 km2) were more substantial than TS1 (1.9%, 1.4 km2) and TS3 (2.3%, 1.3 km2) (Fig. 4) (Table 4 and Fig. 5). The bare soil and vegetation decreased during the study period, with the highest change in TS1 for bare soil (− 5.78%, − 17.15 km2) and vegetation (− 6.75%, The bare soil and vegetation in TS3 decreased by − 8.45% (− 4.49 km2) respectively.

Past LST pattern of in the selected area and tourist spots

Different temperature zones for the entire study area indicate temperatures above 22 °C with an increasing trend (Fig. 6). The temperature class between 12 to 16 °C initially increased to 13.3% from 1990 to 2005, then decreased to 2.1% by 2020. The highest increase in the zone above 28 °C was observed. Generally, the mean temperature rose by 3 °C. The temperature was highest in the built-up area, followed by the bare soil, agriculture, and vegetation, while the water bodies had the least amount of heat stress increase. The results for tourist spots indicate that the mean LST of the built-up area in TS1, TS2, TS3 and TS4 were 18 °C, 19 °C, 22 °C, and 23 °C, respectively for the year 1990. The LST in the built-up areas had increased to 24 °C and 25 °C in TS3 and TS4 (Buner district), while the highest LST recorded at TS4 in Buner as 28 °C (Fig. 6). Overall, the results show the mean LST of TS1, TS2, and TS3 is higher than that of TS4.

Future LULC changes in the study area and tourist spots

The future LULC for the whole study area and tourist spot shows a substantial rise in built-up areas from 2020 to 2050 (Fig. 7). The LULC shows significant changes over the entire study area (Table 3 & Fig. 5). The simulation indicates the urban area will increase by 4.6% and 5.7% respectively, in 2035 and 2050 (Fig. 9) while less agricultural land and greenery were predicted. The modeling results indicate that LULC change is anticipated in the future, potentially detrimental to the climate and biodiversity of the area.

By comparing the future LULC changes of the entire study area (Table. 5) with the tourist spots, the tourist spots have high net changes as compared to the entire study area. Between 2020 and 2035, the built-up area in TS1 and TS2 (Shangla) would have a net change of 2.64% (1.91 km2) and 2.30% (2.90 km2), respectively. In TS3 and TS4 (Buner), there will be a net change of 5.36% (2.85 km2) and 5.66% (2.93 km2) (Table 5 and Figs. 8 and 9). The net change in bare soil and vegetation is towards decline, with a significant reduction in TS1 (− 4.26% bare soil, − 7.87% vegetation, during 2035–2050). and TS3 (− 5.55% bare soil, − 4.00% vegetation). Similarly, net changes in agriculture in TS1 and TS2 (Shangla) will be 2.69% and 12.89% from 2035 to 2050, while in TS3 and TS4 (Buner), it will be 5.24% and 6.67%, respectively.

Future LST trends in the study area and tourist spots

Overall, LST values are projected to exceed 28 °C in most areas, reflecting a shift towards higher temperature zones (Fig. 10). In 2035 and 2050, most of the study area will be covered by LST class of above 31 °C and will expand beyond the built-up area (Fig. 10) which indicates the urban warming effect. Most of the study area will have LST ≥ 28 °C and lower LST classes such as < 25 °C will be further decreased with an increase in higher LST zones (The Fig. 10).

The future projections show an increase in the TS1 and TS2 with LST classes ≥ 31 °C from 62.11% to 80.40% and 63.11% to 78.50% (Table 6) in 2035 and 2050, respectively, which was 30% in 2020. The area for LST class 28 to < 31 °C will decrease from 33.21% to 16.49% (Table 6) from 2035 to 2050, which was 29.45% in 2020. The area for LST class 25 to < 28 °C will be 1.77% and 1.39% in the years 2035 and 2050, There will be no area under LST class < 16 °C (Table 6). Future LST estimates show that while only 27% of the study area was above 28 °C in 2020, but it will rise to 65.23% and 82.20% of the study area will rise to above 31 °C in 2035 and 2050, respectively (Fig. 9). Area with temperatures below 28 °C had a declining trend and will eventually transition to warmer zones.

For TS3 and TS4, LST ≥ 31 °C will expand from 27% in 2020 to about 80% in 2050 (Table 6; Fig. 10), indicating widespread urban warming effects. The predictions of the TS3 and TS4 show a higher temperature zone (i.e. LST ≥ 31 °C) in 2035 and 2050 (Fig. 10), which was only 27% in 2020.

Socio-economic indicators of the study area

Shangla is home to 0.8 million people, with a 1586 km2 area and 41,727.5 hectares under cultivation. The literacy rate of the district is 33.1%. Buner has a population of one million, with an area of 1865 km2, where 55,216.5 hectares are under cultivation. The literacy rate of the district is 46.8% (Table 7 Buner has a total income of 902 million PKR, with an expenditure of 218.57 million, whereas Shangla has a per-year income of 1,668,378.24$, with an expenditure of 218.57 million. Buner wooded land is 41,001 hectares, with a land-use intensity of 42.3%, whereas Shangla has 44,405 hectares of wooded land and 51.7% land-use intensity. Tourism plays a role in the economy of the study area. Buner’s annual income from tourism is 100 million PKR while Shangla’s is 48 million, with an increasing trend. The most significant socio-economic indicators influenced by tourism are forest land, land price, land use pattern, agricultural output, and the environmental conditions.

Discussion

LULC class changes (1990–2020)

The evaluation of LULC change is crucial for comprehending the interaction between humans and nature46. Analyzing the trends, causes, and consequences of these changes on human livelihoods and the environment is essential for sustainable development and natural resource management1,47. The past 30 years LULC trends for the whole study area from 1990 to 2020 (Fig. 5) shows two distinct trends i.e., an increase in the built-up areas (+ 0.8%), agriculture (+ 3.17), and bare soil (+ 0.9%) while a decline in vegetation cover (− 5.0%) (Table 3). The contributing factors are population growth, socio-economic pressures, and deforestation (Table 3). In addition, illegal forest cutting due to lack of government oversight leads to an increase in the bare soil class. These findings back up those who discovered that urban growth is affected by geopolitical and economic variables48,49. Similar LULC changes were also found in the Upper Indus Basin Pakistan50, which found that population growth and shifting economic and political situations have contributed to LULC changes51. The eco-political conditions and population growth are the key factors for urban expansion52. These factors accelerated the urban sprawl in the study area, which continued to be40, where the mixture of rural and urban LULC types became distinct features.

Quick and unorganized tourism development enhanced investments in infrastructure, hence escalating the demand for land. However, this unregulated expansion of tourism, towns and cities resulted in significant risks to natural and cultural sites, affecting the sustainability of tourism. The built-up area has increased in the past 30 years (Fig. 4) in both the tourist spots and the whole study area. The Shangla top (TS1) had a higher increase in built-up area than T2, TS3, and TS4, which seems the result of increasing tourism-related activities and expansion of tourism infrastructure. Consequently, the attractiveness of tourist destinations is decreasing as vegetation cover is converted into highways and constructions, emphasizing a trade-off concerning development and environmental conservation. Similar findings have reported that tourist activities cause land fragmentation, which causes LULC changes48 resulting in environmental disturbances and climate change53. Tourism puts pressure on local land use, leading to natural habitat loss, increased pollution, and adds stress to threatened species. This contributes to the gradual destruction of the landscape on which tourism depends54.

LST changes in study area and tourist spots (1990–2020)

The past pattern results of LST for both the whole study area and the tourist spots are given in Fig. 6. Since 2013, demand for summer vacations in Pakistan has increased artificial surfaces to aid the growth of tourism establishments and second homes in Northern Pakistan41. Hence LULC and LST are more common there. Artificial surfaces increased from 1987 to 2017 due to increased residential sprawl45. The overall study findings indicate an increase in temperature for all LULC classes. The variation in temperature classes exists as there was an increasing trend in high-temperature areas (i.e., above 22 °C) while a decreasing trend in the temperature range below 22 °C (Fig. 3). The study finding shows that temperature has increased due to the landscape modification from non-impervious to impervious surfaces (Fig. 6). Similarly, bare soil has a lower temperature than built-up areas but higher than vegetation and agricultural land. These findings are supported by53,55, who examined the effect of LULC changes on LST in Bangladesh to see if there was a link between LST and LULC categories. This increase in LST suggests a combined effect of climate change and surface modification Fig. 5. It may lead to the formation of Surface Heat Island (SUHI) and Atmospheric Heat Island (ATHI) in the study area. Similar warming effects were also found by56, from the north of China.

The past patterns of LST changes in tourist spots indicate a mean LST increase in all tourist spots. This may be due to increased tourist activities and related construction activities51. According to previous studies, tourists engage in activities and produce consumption habits while visiting a site, which can lead to changes in the area, particularly LULC, that increase LST. This research work supports Sustainable Development Goals (SDSs) to help mitigate and adapt strategies to climate change in ecologically sensitive tourist spots, by identifying the urban expansion, vegetation loss, and agricultural area changes.

Future projections of LULC changes in the study area and tourist spots

The future simulation of LULC changes is significant for urban planning and sustainable development. The present results showed that the built-up area would be 4.55% and 5.74% in 2035 and 2050, respectively (Fig. 7). Similar findings55 recorded an increase in a built-up area in Northern Pakistan. The decline in vegetation and rise in the built-up area would modify the climate of the study area, which may have health and environmental consequences such as asthma, heat stress, and biodiversity decline57.

The annual influx of tourists to four locations is increasing, and the local population significantly relies on the tourism business. The simulation of LULC in tourist spots (for 2035 and 2050) indicates that there would be significant built-up area expansion in all tourist spots, especially in TS4 (Daggar) (Fig. 6). The construction of tourism-related infrastructure and tourist movements affect vegetation and soil58. These activities have triggered LULC changes and increased LST in the study areas. The LULC dynamics and climate variability are still critical issues for current and future sustainable environments58. The projected findings of this study fulfill SDS goals as it helps in urban planning, balancing LULC and LST changes, biodiversity conservation, and in ecosystem health and resilience, with sustainable ecofriendly economic growth in the study area. SDG-11 represents a target for tourist destinations and the entire study region including Pakistan, which is attainable through an integrated approach by encompassing historical, contemporary, and prospective evaluations, where the socio-economic factors are influencing the urban expansion, and have an overall impact on the terrestrial system59.

Future projections LST trends in the study area and tourist spots

The landscape changes lead to an increase in LST48,60 leading to disturbances to the local thermal environment leads to various health and environmental consequences, like soil erosion, natural habitat loss, culture changes, and public health issues61. The findings of LST forecasted for 2035 and 2050 to assess the impact of LULC change on surface radiation levels in the study area. indicate almost 76% and 88% area with the highest temperature zone (i.e., > 31 °C) (Fig. 8), from 27% in the base year 2020. The thermal capacity of LULC is affected by an increase in LST which increases urban warming in the study area62,63. Increased LST is an environmental issue that endangers people, biodiversity, and the ecosystem64. According to the IPCC’s fifth assessment report, warming in South Asia is higher than the global average, which may accelerate glacier melting and precipitation65. This change will ultimately affect the efficiency of the water-dependent sectors such as energy and agriculture production66. The projected changes in LST over the chosen tourism spots, TS1, TS2, TS3, and TS4, show an overall significant warming trend by the years 2035 and 2050. The analysis presents a clear indication of the land area shifting from lower temperature ranges (< 22 °C and 22–25 °C) to higher ranges (≥ 28 °C) with the maximum proportion of the land area being in the category ≥ 31 °C by 2050. In the case of tourism spots, the proportion of areas in the category ≥ 31 °C has risen by more than 15% in most of the cases. The increasing flow of tourists, especially during the summer season, causes disturbance of the natural environment and enhances commercial activities in the study area, further enhancing LST. Similar findings were reported in Turkey67, where tourism enhanced forest land conversion into hotels and restaurants. For example, 88% of the state-owned forest land in Beldibi (Turkey) was declared private land. The increased tourism also alters land-use patterns, resulting in the conversion of forest and agricultural land into built-up areas (Figs. 4 and 5). An overall agricultural land reduction in the tourist areas of the lower Himalayan region is also noted41. Human activities’ especially tourism, have environmental implications. It usually leads to a reduction in vegetation cover and an increase in LST. The unchecked tourism can accelerate the degradation of the environment and enhance its climatic vulnerability68. Our findings identify the dual position of tourism as both an economic driver and environmental stressor, emphasizing the need for developing sustainable practices against these impacts in the concerned regions69. The disappearance of the < 16 °C range and diminishing coverage of colder temperature ranges (Table 6) show intensified thermal stress possibly due to changes in LULC along with global climatic dynamics. Critical implications thus fall on both the local ecosystem and tourism, as rising LST tends to negatively influence biodiversity, visitor comfort, and aesthetic attributes at tourist spots70.

The relationship between landscape, tourism, and socio-economic indicators

Tourism influenced the landscape patterns and socio-economic indicators of the study region. It is a dynamic force that fosters economic and cultural transformation, leading to landscape changes and socio-economic growth71. This growth usually leads to a conflict between economic growth and maintenance of significant landscapes72,73. It is generally agreed that tourism, socio-economic development, and landscape modification would not be possible without the physical conditions of an area including pine forests, and humid climate. Studies72,73,74 points out that tourism is just one of many forces that drive change, and it is difficult to separate its consequences from other transforming forces. For example, the number of tourists related activities on the East African Coast has increased, leading to rapid economic growth through increased investments in tourist facilities, followed by increased property values, resulting in LULC changes54.

Tourism, LULC, and LST changes are interconnected as tourism demands infrastructure, which in turn raises land prices, putting pressure on farmers to convert their land into restaurants and hotels, leads to higher LST54,74. Resultantly, many low-income farmers have sold their fields due to high land prices, and went to work in the tourism industry, potentially leading to soil erosion, natural habitat loss, cultural shifts, and increased pollution63. Tourism negatively affects forested areas, primarily through deforestation caused by land clearing and fuel consumption. For instance, the construction of a ski resort required significant land removal for associated lodging and infrastructure. Similarly, coastal marshes are drained and filled due to a lack of suitable tourism amenities and infrastructure. These actions destabilize the local ecosystem and inflict long-term ecological damage75. According to the expected results of the LULC reforms, the tourist attractions will be converted into buildings and infrastructure. The conversion of natural forests into artificial land would increase the temperature of tourist locations. These changes will result in fewer tourist attractions, that will directly impact on the local population’s long-term incomes. A study in Turkey76 mentioned that tourism is the main driver of LULC and emphasis the essential role of LST in sustainable planning and management.

Conclusions

This study concluded that both the study area and its tourist spots have experienced significant changes in the LULC and LST. The built-up areas have increased, while the vegetation has decreased, with the highest mean LST observed in the built-up areas and the lowest in the water bodies during the last three decades. In the LULC modeling simulation, the built-up areas of the entire study region will continue to increase between 2035 and 2050, and the LST above 28 °C would cover over 80% of the total area, in the coming thirty years. In tourist areas, the LULC and LST trends showed an increase in the built areas, specifically in the TS1, in the past 30 years. The simulation analysis concluded that TS4 would have the highest LULC changes in the future. The current and future LST results concluded that the maximum temperature is found in TS4, while the maximum temperature would be in TS1, respectively. These reported transformations are mostly driven by tourism-related activities, influencing both past and future LULC and LST changes in this region. Additional land is being pushed towards the high-temperature zone as a result of the expansion of either built-up or bare soil territory. If current LST trends continue, the entire region could convert to hotter zones. Strategies like a compact town, such as de-centralizing urban areas and plantations, could be an appropriate approach for slowing the formation of high-temperature zones. To create a sustainable policy, the tourism sector and the environment will both benefit from the LULC and LST research. Future research should explore the consequences of built-up areas expansion and urban warming on local residents and develop urban planning, sustainable tourism, and climate-responsive policies at both the regional and national levels.

Data availability

Data is provided within manuscript.

References

Roy, P. S. et al. Anthropogenic land use and land cover changes—A review on its environmental consequences and climate change. J. Indian Soc. Remote Sens. 50, 1615–1640 (2022).

Ullah, S., Khan, M. & Qiao, X. Examining the impact of land use and land cover changes on land surface temperature in Herat city using machine learning algorithms. GeoJournal 89, 225 (2024).

Zhang, H. et al. Analysis of the trends and driving factors of cultivated land utilization efficiency in Henan Province from 2000 to 2020. Land 13, 2109 (2024).

Winkler, K., Fuchs, R., Rounsevell, M. & Herold, M. Global land use changes are four times greater than previously estimated. Nat. Commun. 12, 2501 (2021).

Luo, Q. et al. Rural depopulation has reshaped the plant diversity distribution pattern in China. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 215, 108054 (2025).

Goeldner, C. R. & Ritchie, J. B. Tourism: Principles, practices, philosophies (Wiley, Hoboken, 2011).

Gössling, S. et al. Tourism and water use: Supply, demand, and security. An international review. Tour. Manag. 33, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2011.03.015 (2012).

Chu, L., Oloo, F., Chen, B., Xie, M. & Blaschke, T. Assessing the influence of tourism-driven activities on environmental variables on Hainan Island, China. Remote Sens. 12, 1–22 (2020).

Africa, S. & Zealand, N. The Geography of Tourism and Recreation 4th edn. (Routledge, Milton Park, 2014).

Gössling, S. et al. The eco-efficiency of tourism. Ecol. Econ. 54, 417–434 (2005).

Żemła-Siesicka, A. Tourism landscape footprint in the archaeological landscape. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 103, 107255 (2023).

Kowalczyk-anio, J. Rethinking tourism-driven urban transformation and social tourism impact: A scenario from a CEE city. Cities 34, 104178 (2023).

Qiao, G., Hou, S., Huang, X. & Jia, Q. Inclusive tourism: Applying critical approach to a Web of Science bibliometric review. Tour. Rev. https://doi.org/10.1108/TR-04-2024-0332 (2024).

Boavida-Portugal, I., Rocha, J. & Ferreira, C. C. Exploring the impacts of future tourism development on land use/cover changes. Appl. Geogr. 77, 82–91 (2016).

Ullah, S., Qiao, X. & Abbas, M. Addressing the impact of land use land cover changes on land surface temperature using machine learning algorithms. Sci. Rep. 14, 18746 (2024).

Ullah, S., Qiao, X. & Tariq, A. Impact assessment of planned and unplanned urbanization on land surface temperature in Afghanistan using machine learning algorithms: A path toward sustainability. Sci. Rep. 15, 3092 (2025).

Lacerda, L. I. A. et al. Urban forest loss using a GIS-based approach and instruments for integrated urban planning: A case study of João Pessoa, Brazil. J. Geogr. Sci. 31, 1529–1553 (2021).

Filho, W. L. et al. sustainability addressing the urban heat islands effect: A cross-country assessment of the role of green infrastructure. Sustainability 13, 753. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13020753 (2021).

Cetin, M. The effect of urban planning on urban formations determining bioclimatic comfort area’s effect using satellitia imagines on air quality: A case study of Bursa city. Air. Qual. Atmos. Health 12, 1237–1249 (2019).

Shohan, A. A. A., Hang, H. T., Alshayeb, M. J. & Bindajam, A. A. Spatiotemporal assessment of the nexus between urban sprawl and land surface temperature as microclimatic effect: Implications for urban planning. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 31, 29048–29070 (2024).

Njoku, E. A. & Tenenbaum, D. E. Quantitative assessment of the relationship between land use/land cover (LULC), topographic elevation and land surface temperature (LST) in Ilorin, Nigeria. Remote Sens. Appl. 27, 100780 (2022).

Ara, S., Alif, M. A. U. J. & Islam, K. M. A. Impact of tourism on LULC and LST in a coastal Island of Bangladesh: A geospatial approach on St. Martin’s Island of Bay of Bengal. J. Indian Soc. Remote Sens. 49, 2329–2345 (2021).

Li, R. Q. et al. Quantification of the impact of land-use changes on ecosystem services: A case study in Pingbian County, China. Environ. Monit. Assess. 128, 503–510 (2007).

Gao, E. et al. Spatio-temporal evolution monitoring and analysis of tidal flats in Beibu Gulf from 1987 to 2021 using multisource remote sensing. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 17, 6099–6114 (2024).

Gupta, A. analyzing land use/land cover dynamics in mountain tourism areas: a case study of the core and buffer zones of Sagarmatha and Khaptad National Parks, Nepal. Sustainability 16, 10670 (2024).

Pakistan Bureau of Statistics (PBS). Statistical Yearbook 2023. (Government of Pakistan, 2023). https://www.pbs.gov.pk/publications.

Afzaal, M., Haroon, M. A. & Ul Zaman, Q. Interdecadal oscillations and the warming trend in the area-weighted annual mean temperature of Pakistan. Pak. J. Meteorol. 6, 13–19 (2009).

Sher, H. Traditional resources evaluation of district Shangla, Pakistan. Afr. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 7, 2928–2936 (2013).

Ullah, W. et al. Analysis of the relationship among land surface temperature (LST), land use land cover (LULC), and normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI) with topographic elements in the lower Himalayan region. Heliyon 9, e13322 (2023).

Akbar, G. Problems and potential of agriculture for improving livelihood in Malakand division, Pakistan. Paki. J. Agric. Res. 33, 351–361 (2020).

Shangla now a popular tourist destination: DPO. DAWN.COM (6 January 2020). Available at: https://www.dawn.com/news/1526474. Accessed 10 October 2023.

Ahmad, L. G. & Eshlaghy, A. T. Using three machine learning techniques for predicting breast cancer recurrence. J. Health Med. Inform. 4, 3 (2013).

Foody, G. M. Status of land cover classification accuracy assessment. Remote Sens. Environ. 80, 185–201 (2002).

Hussain, M., Chen, D., Cheng, A., Wei, H. & Stanley, D. ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing Change detection from remotely sensed images: From pixel-based to object-based approaches. ISPRS J. Photogr. Remote Sens. 80, 91–106 (2013).

Tariq, A. & Mumtaz, F. Modeling spatio-temporal assessment of land use land cover of Lahore and its impact on land surface temperature using multi-spectral remote sensing data. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 30, 23908–23924 (2023).

Srivastava, P. K., Han, D., Rico-Ramirez, M. A., Bray, M. & Islam, T. Selection of classification techniques for land use/land cover change investigation. Adv. Space Res. 50, 1250–1265 (2012).

Guha, S. & Govil, H. A long-term monthly analytical study on the relationship of LST with normalized difference spectral indices. Eur. J. Remote Sens. 54, 487–512 (2021).

Tariq, A. & Mumtaz, F. A series of spatio-temporal analyses and predicting modeling of land use and land cover changes using an integrated Markov chain and cellular automata models. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 30, 47470–47484 (2023).

Sobrino, J. A., Jiménez-Muñoz, J. C. & Paolini, L. Land surface temperature retrieval from LANDSAT TM 5. Remote Sens. Environ. 90, 434–440 (2004).

Salama, M. S. et al. Decadal variations of land surface temperature anomalies observed over the Tibetan Plateau by the Special Sensor Microwave Imager (SSM/I) from 1987 to 2008. Clim. Change 114, 769–781 (2012).

Ullah, S. et al. Remote sensing-based quantification of the relationships between land use land cover changes and surface temperature over the lower Himalayan region. Sustainability 11, 5492 (2019).

Joorabian Shooshtari, S., Silva, T., Raheli Namin, B. & Shayesteh, K. Land use and cover change assessment and dynamic spatial modeling in the Ghara-su Basin, Northeastern Iran. J. Indian Soc. Remote Sens. 48, 81–95 (2020).

Atef, I., Ahmed, W. & Abdel-Maguid, R. H. Future land use land cover changes in El-Fayoum governorate: A simulation study using satellite data and CA-Markov model. Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess. 38, 651–664 (2024).

Maduako, I. D. Simulation and prediction of land surface temperature (LST) dynamics within Ikom City in Nigeria using artificial neural network (ANN). J. Remote Sens. GIS 5, 3–10 (2015).

Ullah, S. et al. Analysis and simulation of land cover changes and their impacts on land surface temperature in a lower Himalayan region. J. Environ. Manag. 245, 348–357 (2019).

Tahir, Z. et al. Predicting land use and land cover changes for sustainable land management using CA-Markov modelling and GIS techniques. Sci. Rep. 15, 3271 (2025).

Liu, S. et al. Understanding Land use/Land cover dynamics and impacts of human activities in the Mekong Delta over the last 40 years. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 22, e00991 (2020).

Dey, J. et al. Geospatial assessment of tourism impact on land environment of Dehradun, Uttarakhand, India. Environ. Monit. Assess. 190, 1–10 (2018).

Ullah, W. et al. Land use land cover and land surface temperature changes and their relationship with human modification in Islamabad Capital Territory, Pakistan. Braz. J. Biol. 84, e281700 (2024).

Rehman, A. et al. Land-use/land cover changes contribute to land surface temperature: a case study of the upper Indus Basin of Pakistan. Sustainability 14, 934 (2022).

Zhang, A. et al. Automated pixel-level pavement crack detection on 3D asphalt surfaces using a deep-learning network. Comput. Aided Civ. Infrastruct. Eng. 32, 805–819 (2017).

Chen, L., Chen, T., Lan, T., Chen, C. & Pan, J. The contributions of population distribution, healthcare resourcing, and transportation infrastructure to spatial accessibility of health care. INQUIRY J. Health Care Organ. Provis. Financ. 60, 1–19 (2023).

Al Kafy, A. et al. Predicting changes in land use/land cover and seasonal land surface temperature using multi-temporal landsat images in the northwest region of Bangladesh. Heliyon 7, e07623 (2021).

Vijay, R. et al. Assessment of tourism impact on land use/land cover and natural slope in Manali, India: A geospatial analysis. Environ. Earth Sci. 75, 1–9 (2016).

Khan, M. et al. Trends and projections of land use land cover and land surface temperature using an integrated weighted evidence-cellular automata (WE-CA) model. Environ. Monit. Assess. 194, 120 (2022).

Ren, G. Y. et al. Urbanization effects on observed surface air temperature trends in north China. J. Clim. 21, 1333–1348 (2008).

Fattah, Md. A. & Morshed, S. R. Assessment of the responses of spatiotemporal vegetation changes to climatic variability in Bangladesh. Theor. Appl. Climatol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00704-022-03943-7 (2022).

Henderson, J. C. Communism, heritage and tourism in East Asia. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 13, 240–254 (2007).

Kanga, S. et al. Understanding the linkage between urban growth and land surface temperature—A case study of Bangalore City, India. Remote Sens. 14, 4241 (2022).

Ullah, S., Abbas, M. & Qiao, X. Impact assessment of land-use alteration on land surface temperature in Kabul using machine learning algorithm. J. Spat. Sci. 00, 1–23 (2024).

Duan, X. et al. A geospatial and statistical analysis of land surface temperature in response to land use land cover changes and urban heat island dynamics. Sci. Rep. 15, 4943 (2025).

Stewart, I. D. & Oke, T. R. Local climate zones for urban temperature studies. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 93, 1879–1900 (2012).

Zhou, D. et al. Satellite remote sensing of surface urban heat islands: Progress, challenges, and perspectives. Remote Sens. 11, 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs11010048 (2019).

Grimmond, S. Urbanization and global environmental change: Local effects of urban warming. Geogr. J. 173, 83–88 (2007).

IPCC. Climate Change 2007: Mitigation of Climate Change. Contribution of Working Group III to the FourthAssessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (Cambridge University Press, 2007). https://www.globalchange.gov/browse/reports/ipcc-climate-change-2007-mitigation-climate-change.

CDKN. The IPCC’s Fifth Assessment Report: What’s in it for South Asia? (Climate & Development Knowledge Network, 2014). https://cdkn.org/resource/highlights-ipcc-ar5-south-asia.

Cinar, I., Ardahanlıoğlu, Z. R. & Toy, S. Land use/land cover changes in a Mediterranean summer tourism destination in Turkey. Sustainability (Switzerland) 16, 1–16 (2024).

Stefanica, M., Sandu, C. B., Butnaru, G. I. & Haller, A. P. The nexus between tourism activities and environmental degradation: Romanian tourists’ opinions. Sustainability (Switzerland) 13, 1–19 (2021).

Baloch, Q. B. et al. Impact of tourism development upon environmental sustainability: A suggested framework for sustainable ecotourism. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 30, 5917–5930 (2023).

Maoela, M. A., Nhamo, G., Chapungu, L. & Madikizela, A. Tourists’ perceptions of climate change awareness, impact, and response mechanisms in South African national parks. Dev. South Afr. 42(1), 1–23 (2024).

Jehan, Y., Batool, M., Hayat, N. & Hussain, D. Socio-economic and environmental impacts of tourism on local community in Gilgit Baltistan, Pakistan: A local community prospective. J. Knowl. Econ. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13132-021-00885-9 (2022).

Frey, K. E. & Smith, L. C. How well do we know northern land cover? Comparison of four global vegetation and wetland products with a new ground-truth database for West Siberia. Glob. Biogeochem Cycles 21, 1–15 (2007).

Adnan Hye, Q. M. & Ali Khan, R. E. Tourism-led growth hypothesis: A case study of Pakistan. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 18, 303–313 (2013).

Leong, C., Takada, J. I., Hanaoka, S. & Yamaguchi, S. Impact of tourism growth on the changing landscape of a world Heritage Site: Case of Luang Prabang, Lao PDR. Sustainability (Switzerland) 9, 1–12 (2017).

Ndhlovu, P., Chigwenya, A., Makuvaza, S. & Mudzengerere, F. H. Tourism development activities in Chisuma communal area in Hwange Rural District, Zimbabwe. Afr. J. Econ. Sustain. Dev. 4, 141 (2015).

Levent, T. The role of tourism planning in land-use / land-cover changes in the Kızkalesi tourism destination. Land 13, 151 (2024).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the Researchers Supporting Project number (RSPD2025R951), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

Funding

The authors acknowledge the Researchers Supporting Project number (RSPD2025R951), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W.U. wrote the original draft of the manuscript, K.A. S.U. and M.T.R. worked on conceptualization, data curation, and formal analysis; W.U. and S.U. did investigation and methodology; A.A.T. and M.A.A.W managed the project administration, resources, and software; K.A. and supervision, validation, and review.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ullah, W., Ahmad, K., Tahir, A.A. et al. Impacts of tourism on LULC and LST dynamics in district Buner and Shangla, Pakistan. Sci Rep 15, 9304 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-94230-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-94230-8

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Integrating Google Earth Engine and Machine Learning To Map LULC and LST Dynamics in the Arid Heartland of Pakistan

Earth Systems and Environment (2026)

-

Evaluating the impact of urbanization patterns on LST and UHI effect in Afghanistan’s Cities: a machine learning approach for sustainable urban planning

Environment, Development and Sustainability (2025)

-

The effects of Socio-economic conditions and land use pattern on land surface temperature and urban heat Island at saint martin’s Island in Bangladesh

Theoretical and Applied Climatology (2025)