Abstract

The objective of this study is to develop an efficient gradient spiral-structured Ni/CeO2 catalyst for CO2 methanation. The spiral-structured Ni/CeO2 catalysts were prepared by the gradient coating method. The process employs a triple-passed operation for steam trapping to increase the CH4 product at flow rates from 100 to 3000 ml/min. At a low flow rate (100 ml/min), a triple-passed reactor’s CO2 conversion efficiency (98.5%) and CH4 selectivity (99.9%) are slightly greater than those of a single-passed reactor (96.4% and 99.9%, respectively). When operating at a high flow rate of 3000 ml/min, a triple-passed reactor can reach up to 83.4% CO2 conversion efficiency and 94.9% CH4 selectivity, whilst a single-passed reactor can only achieve 64% CO2 conversion and 87.4% CH4 selectivity. In addition, the spiral structure can enhance heat transfer, eliminating hotspots as well as improving mass transfer by swirling flow. The development of gradient coating could be beneficial for conducting thermal energy from a thick-coated front spiral-catalyst to a thinner-coated terminal spiral-catalyst. Furthermore, the steam trapping would further increase CO2 conversion as well as CH4 selectivity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

CO2 methanation has been determined to be a successful method for the total removal of CO2. The technique can not only reduce emissions of CO2 and greenhouse gases, but also provide future energy with ecologically friendly effects1. CO2 methanation is an exothermic reaction2, producing CH4 and H2O as presented in Eq. (1). The combination of an endothermic reversed water gas shift (RWGS) reaction and an exothermic CO methanation, as indicated by Eqs. (2) and (3), respectively, is the most accepted mechanism of the methanation reaction2.

Catalysts are essential in CO2 methanation because they accelerate reaction kinetics and improve selectivity. The catalyst should be highly active, stable, and selective for methane production while limiting unwanted by-products. A number of noble metals, including Rh3, Ru4 and Pd5, have found extensive use for CO2 methanation because of their superior catalytic activities and low-temperature CH4 selectivity. However, they have limited large-scale industrial applications due to their high cost. However, non-noble metals like nickel (Ni) have attracted much attention for applying in CO2 methanation, as they exhibit high activities, and their low cost makes them scalable to industrial scale6,7. Still, there are certain obstacles in the way of enhancing the CO2 methanation performance of Ni-based catalysts. CO2 methanation is an exothermic reaction that results in carbon formation and Ni particle sintering, which deactivates the catalyst during CO2 methanation8. In addition, enhancing CO2 methanation requires consideration of the catalyst supports. According to earlier research9,10, oxygen vacancies are crucial for CO2 methanation since CO2 and CO dissociate on oxygen vacancies. Cerium oxide (CeO2) has unique properties in storing and releasing oxygen with a large capacity, so it is frequently used as a catalyst support for CO2 methanation in order to encourage both CO2 activation and CO2 adsorption11,12.

As mentioned earlier, due to the highly exothermic heat of CO2 methanation, inevitably the temperature inside the reactor rapidly rises, which causes an extremely high temperature zone, called hotspots. The spots would cause thermal sintering of catalyst particles and reduce CO2 conversion and CH4 yield due to the exothermic nature of the reaction. To prolong a catalyst’s lifetime and achieve high CH4 selectivity, thermal management of hotspots is important. In general, packed-bed reactors remain difficult to control heat transfer in high-temperature zones due to the low heat conductivity of catalyst bed materials13. Recently, structured catalyst reactors exhibited excellent catalytic performance for CO2 methanation, especially catalyst stability, attributed to improved heat transfer by the conduction mode of the structured substrate14. In our previous research15, honeycomb-structured Ni-based catalysts were studied for CO2 methanation. It was found that the random-flow channels of the honeycomb structure can increase the catalytic performance, resulting in a high CO2 conversion. We also reported that spiral-structured catalysts with Ni/CeO2 loaded on spiral aluminum substrates presented a high methanation activity because the swirling flow of spiral structures improved heat and mass transfer abilities16.

Herein, we develop spiral-structured Ni/CeO2 catalysts by applying the gradient coating, which consists of a thick-coated front spiral catalyst and a thinner-coated terminal spiral catalyst, to enhance heat and mass transfer and to prevent catalyst deactivation from the hotspots in methanation. Furthermore, a triple-passed operation of steam trapping techniques is employed to improve the CH4 production by removing the by-product of water.

Experimental

Materials and chemicals

Cerium oxide (CeO2, JRC-CEO-2) was purchased and used as received for catalyst support. Nickel nitrate hexahydrate (Ni(NO3)2.6H2O, ≥ 98%, Sigma-Aldrich) was used as the nickel precursor for the catalyst preparation. The aluminum plate (JIS A1100P84 H18) was used as a spiral plate (50 mm × 7 mm) for catalyst coating. Isopropanol (IPA, AR grade, QReC) was used as a dispersal solution during the wash-coat method. Sodium hydroxide (NaOH, GR, Merck) and hydrochloric acid (HCl, 37%, AR grade, QReC) were used for cleaning and activating, respectively, the surface of spiral Al plates.

Preparation of gradient-coated spiral-structured Ni/CeO2 catalysts

CeO2 was used as the catalyst support to prepare the Ni catalysts by wetness to dryness impregnation, which were denoted as Ni/CeO2. In detail, 9.0 g of CeO2 was dispersed into the Ni precursor solution, which contains 4.96 g of Ni(NO3)2.6H2O and 50 ml of DI water. The mixture was then stirred at 80°C to evaporate the DI water. When the solution turned into a slurry mixture, it was physically mixed with a Teflon stick to make the mixture homogenous and dried. After the mixture dried, it was then calcined at 500°C for 3 h (heating rate of 10°C/min). Photographs of each step of Ni/CeO2 catalyst preparation are shown in Fig. 1a.

The preparation of spiral Al plates is illustrated in Fig. 1b. The aluminum plate was cut to the size of 50 mm × 7 mm and twisted at 360° by using the bench vise to obtain the spiral Al substrate. The spiral aluminum substrates were then washed and activated with 5-min of 0.8 N NaOH and 30-min of 2.8 N HCl solutions, respectively.

To coat Ni/CeO2 on the activated surface of the spiral substrate, the wash-coat method was applied16 as shown in Fig. 1c. The activated spiral substrate was immersed in a slurry mixture of prepared Ni/CeO2 and IPA. Then it was blown and dried by a dryer. The cycle of dipping and drying was further continued until the spiral substrate was coated with the desired weight of Ni/CeO2. In this work, gradient-coated spiral catalysts were used in CO2 methanation; hence, the Ni/CeO2 was coated on the spiral Al plates at different weights, that is, 120 mg and 180 mg.

Characterization of Ni/CeO2 catalyst

The as-prepared Ni/CeO2 catalysts were characterized comprehensively using several techniques, including X-ray diffraction (XRD, BENCHTOP, D2 PHASER, BRUKER), H2 temperature-programmed reduction (H2-TPR, BEL-CAT-B), Raman spectroscopy (PerkinElmer® Spectrum™GX), field emission scanning electron microscope and energy dispersive x-ray spectrometer (FESEM-EDS, JEOL JSM-7610F, Oxford X-Max 20 model), transmission electron microscopy (TEM, JEOL, JEM-2100 Plus), N2 adsorption-desorption (TriStar II 3020 Version 3.02), inductively coupled plasma-optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES, Avio 550 Max) and atomic force microscopes (AFM, Park system Fx40).

Catalytic test of CO2 methanation

A single-passed reactor

There were two types of experimental setups for CO2 methanation in this study: a single-passed reactor and a triple-passed reactor, as presented in Fig. 2. Regarding the single-passed reactor (Fig. 2a) and the triple-passed reactor (Fig. 2b), the CO2 methanation was carried out in one reactor constructed from a quartz tube (i.d. = 8 mm, length = 900 mm). The as-prepared spiral-structured Ni/CeO2 catalysts were placed inside the reactor in the order of 180 mg, followed by 120 mg (the total catalyst weight was 300 mg). It should be noted that using 180 mg and 120 mg catalysts for gradient coating in this research is intended to provide a suitable balance of catalytic activity while preventing the creation of hotspots as we proposed. The gradient coating promotes heat convection, lowering the risk of overheating and ensuring catalytic performance and longevity. In brief, the 180 mg catalyst produces higher catalytic activity and heat, whereas the 120 mg catalyst serves to reduce the intensity of the reaction in areas that exhibit excessive heat.

The quartz tube reactor, which carried pieces of spiral catalyst, was positioned horizontally within a tube furnace and fitted with a digital temperature controller (KP1000 series, Chino). A type K thermocouple was used to track the temperatures of the spiral catalyst bed. Prior to the CO2 methanation process, the as-prepared spiral catalysts were reduced in situ with a 100 vol% H2 flow at 100 ml/min at 500°C (10°C/min) for an hour. The feed gas (CO2/H2 = 1/4 molar ratio) was then injected into the reactor at a total flow rate of 100 ml/min, corresponding to a weight hourly space velocity (WHSV) of 20,000 ml/g·h. CO2 methanation was performed at 200–500°C under atmospheric pressure. The outlet gas had steam as a byproduct, so it was cooled and trapped by a condenser before being manually injected into a Gas Chromatography (GC-TCD 8A, Shimadzu) by a micro syringe (MS-GAN025, ITO).

A triple-passed reactor

Three quartz tube reactors were set up in a tube furnace. Each reactor contained pieces of gradient-coated spiral-structured Ni/CeO2 catalysts. The conditions of H2 reduction and CO2 methanation were similar to those of a single-passed reactor. However, the outlet gas of the R1 was used as the inlet gas for the R2 reactor, and the outlet gas of the R2 reactor was used as the inlet gas for the R3 reactor. Furthermore, as illustrated in Fig. 2b, the steam in each reactor’s outlet gas was removed by a cooling trap before passing through the sampling port and the following reactor.

The CO2 methanation performances of these two configurations of single-passed and triple-passed reactors were investigated at high reactant feed (CO2/H2) flow rates of 500, 1000, 1500, 2000, 2500, and 3000 ml/min at 350°C. In addition, the pressure drop between the gas inlet and outflow locations was measured using a manometer (DT-8820) in order to investigate the flow behavior during methane production at different flow rates.

The catalytic performance in terms of CO2 conversion (\(\text X_{{\text {CO}_{2}}}\)), CH4 selectivity (\(\text S_{{\text {CH}_{4}}}\)), CO selectivity (SCO), and carbon balance was calculated following Eqs. (4–7)17, respectively.

where [CO2]in and [CO2]out are the CO2 concentrations (mol/min) at the input and output gases. The concentrations (mol/min) of CH4 and CO outlets are denoted by [CH4]out and [CO]out, respectively. Fin and Fout are the total molar flow rates of the input and output gases, respectively.

The mass-normalized reaction rate (rm) was determined following Eq. (8).

where [CO2]in is the CO2 inlet concentration (mol/min). \(\text X_{{\text {CO}_{2}}}\) represents CO2 conversion. mcat represents the amount of catalyst in grams.

Results and discussion

Investigation of pristine CeO2 support and Ni/CeO2 catalyst

The crystal structure investigation

Figure 3 shows the employing of X-ray diffraction (XRD) to investigate the crystal phase information of pristine CeO2 supports along with Ni/CeO2 catalysts in both calcined and reduced forms. The diffraction characteristic peaks of 2θ found at 28.6°, 33.1°, 47.5°, 56.4°, 59.2°, 69.5°, 76.8°, and 79.2° corresponded to the CeO218. These peaks can be indexed to the lattice planes of a typical cubic fluorite structure as follows: (111), (200), (220), (311), (222), (400), (331), and (420), respectively, indicating that eight oxygen atoms surround each metal cation19. After loading Ni on the CeO2 support (calcined Ni/CeO2), the specific peaks of 2θ were presented at 37.2°, 43.3°, and 62.9°. These peaks corresponded to the NiO form with the weak diffraction peaks at lattice planes of (100), (200), and (220), respectively20. Before methanation, the calcined Ni/CeO2 catalyst must be reduced by H2 gas to transform NiO to metallic Ni, and the catalyst after H2 reduction will be called reduced Ni/CeO2. The distinctive metallic Ni diffraction peaks in the reduced Ni/CeO2 catalyst were located at 44.7° and 52.1° (JCPDS no. 01-071-4655). There are no NiO peaks left after H2 reduction, which means that the catalyst is completely reduced.

The crystallite sizes of CeO2, NiO, and Ni before and after H2-reduction are shown in Table 1. The Scherrer equation was used to compute the crystallite sizes of CeO2, NiO, and Ni, which were found at the 2θ peaks of 28.6°, 43.3°, and 44.7°, respectively. The pristine CeO2 shows a small crystallite size at 7.4 nm. After calcination to form calcined Ni/CeO2, the CeO2 crystallite size increased from 7.4 to 8.1 nm. This is because calcination is a thermal treatment process, as it was proceeded at 500°C for 3 h at atmosphere, causing CeO2 particles to migrate and coalesce, resulting in a larger crystallite size21. Similarly, when the calcined Ni/CeO2 was then reduced by H2 at 500°C for another 1 h to form reduced Ni/CeO2, the crystallite size of CeO2 kept rising to 9.9 nm due to this high temperature can also induce sintering effects, leading to the coalescence of CeO2 crystallites and an increase in their size. In addition, the H2 reduction process generates oxygen vacancies in the CeO2 lattice, which can enhance atomic mobility and facilitate crystallite growth. This can be confirmed by Raman spectra (see Fig. 6b and Table 3), showing that oxygen vacancies (the ratio between peak intensities of the D and F2g mode, ID/IF2g) of reduced Ni/CeO2 are a bit higher than that of the calcined one. The prior research22 also affirmed that Ni2+ species can enter the CeO2 lattice to replace Ce4+ and create oxygen vacancies to balance charges.

The crystallite size of NiO was 21.6 nm before H2 reduction. After H2 reduction, the NiO transformed to metallic Ni. The metallic Ni from reduced Ni/CeO2 presents a crystallite size of 28.3 nm, which is a bit larger than that of NiO. This is because of Ni atom diffusion from NiO to Ni at high temperatures during the H2 reduction23,24. After the H2 reduction process, although the Ni and CeO2 crystallite sizes of the reduced catalyst were slightly larger, causing a loss of some surface area, they still perform well in CO2 methanation25.

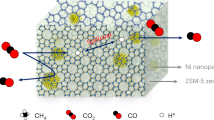

The morphology of pristine CeO2 support and Ni/CeO2 catalyst

As shown in Fig. 4, the morphologies of the CeO2 support and Ni/CeO2 catalyst were examined using SEM and TEM techniques. The Ni particle size distribution (nm) is measured from ImageJ software with a sample number of 50 (N = 50). Since the pristine CeO2 support was produced commercially, it was used exactly as given. The SEM image in Fig. 4a showed the agglomeration of CeO2, which consisted of aggregating CeO2 nanoparticles. Following Ni impregnation, known as calcined Ni/CeO2, the SEM image in Fig. 4b shows that the Ni particles were distributed over the surface of CeO2 supports. High-magnification SEM image that was placed into Fig. 4b further demonstrated the presence of spherical Ni particles. As we may know, the SEM technique is used for surface morphological characterizations; hence, to study the internal structure of the reduced form of Ni/CeO2, the TEM technique was employed. TEM micrographs in Fig. 4c show the dark spots of spherical Ni particles distributed over CeO2 supports. However, some locations exhibited agglomeration of black dots due to the development of crystals from NiO to Ni during the H2 reduction process23,24. The Ni particle size distribution, measured from reduced Ni/CeO2, is presented in Fig. 4d. This finding illustrates that Ni particle sizes are in between ~20 and ~60 nm. The average size of Ni particles is 32.1 ± 10.0 nm, and most Ni particle sizes are typically greater than that of the Ni crystallite size of reduced Ni/CeO2 (28.3 nm) that is measured from the XRD technique (see Table 1). As we know, Ni particles are the entirely physical entity or aggregate of Ni that can be made from one or more crystallites. In addition to the SEM and TEM results, the ICP-OES analysis demonstrated that the actual Ni loading amount was 10.3% (mass), as indicated in Table 2, confirming that Ni species were successfully distributed on the CeO2 surface.

Porosity of pristine CeO2 and its Ni/CeO2 catalysts

To study the porosity of the pristine CeO2 and Ni/CeO2 catalysts (calcined form and reduced form), N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms, BET surface areas (SBET), total pore volumes, and pore size distribution (PSD) are shown in Fig. 5 and Table 2.

Figure 5a illustrates that pristine CeO2 exhibits type IV isotherms with a hysteresis loop, which may indicate that it contains mesoporous structures26. Incorporating Ni on pristine CeO2 to form Ni/CeO2 catalyst influences the textural properties, which can be observed through changes in N2 adsorption-desorption isotherms, total pore volumes, and PSDs. Calcined Ni/CeO2 (prepared from wetness to dryness impregnation) and reduced Ni/CeO2 (obtained from H2 reduction) show similar N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms; that is, type IV isotherms with a hysteresis loop. However, N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms of pristine CeO2 display higher adsorption capacity (cm3/g STP) than those of calcined Ni/CeO2 and reduced Ni/CeO2. This is due to loading Ni onto pristine CeO2, which could affect the pore structure and SBET, leading to decreased N2 adsorption capacity. Table 2 shows that after Ni impregnation, SBET of pristine CeO2 significantly decreases, from 155.7 to 89.1 m2/g (for calcined form) and 87.5 m2/g (for reduced form). Total pore volumes also exhibit the same decreasing trend. The decrease in SBET and total pore volumes indicates that the addition of Ni to the CeO2 surface resulted in mesopore blockage, suggesting that Ni particles are distributed over the CeO2 surface and partially block the porosity of the CeO227. On the other hand, PSDs of calcined Ni/CeO2 (6.9 nm) and reduced Ni/CeO2 (7.0 nm) are larger than that of pristine CeO2 (5.5 nm) as presented in Fig. 5b together with Table 2. To compare PSDs between pristine CeO2 and calcined Ni/CeO2, it was found that during the calcination of the as-prepared Ni/CeO2, the Ni precursor decomposes to form nickel oxide (NiO) particles, which are dispersed on the surface and within the pores of CeO2, leading to a larger pore size. After H2 reduction of the calcined Ni/CeO2 catalyst, the PSD of reduced Ni/CeO2 is a bit larger than that of calcined Ni/CeO2. This is due to NiO particles being transformed into metallic nickel (Ni), which can influence the pore structure. The H2 reduction process could lead to the creation of additional pore volume or the enlargement of existing pores due to the migration and sintering of Ni particles28. It can be concluded that the Ni/CeO2 catalysts still perform an excellent CO2 methanation even if loading Ni to the pristine CeO2 affects the catalyst’s porosity.

Metal-support interaction and oxygen vacancies

The interactions between Ni and CeO2 in NiO–CeO2 and its reduction characteristics are examined by H2-TPR characterization at 50–900°C, as shown in Fig. 6 and Table 3. The temperature range of 200–600°C is usually where the reduction peaks of NiO catalysts supported by CeO2 are observed20. Regarding the H2-TPR result in Fig. 6a, three reduction peaks were denoted as α, β, and γ. The α peak, which is detected below 250°C, is attributed to the reduction of surface oxygen species. These species may be linked to the oxygen vacancies created by the partial substitution of Ni2+ ions for Ce4+ ions29. The Ni/CeO2 catalyst displayed two distinct α peaks at 243.7°C and 259.1°C. These two peaks shifted to a high reduction temperature in the α zone, demonstrating a strong relationship between metal and support on the surface of the catalyst17. The main reduction peak of Ni/CeO2 catalysts was seen at a temperature between 250°C and 400°C, which corresponds to β-NiO. The β-NiO peak is ascribed to the interaction between NiO and CeO2, also known as the Ni–Ce–O30. The temperature of the β peak over Ni/CeO2 was 312.1°C, indicating a strong interaction between NiO and CeO231, reported in Table 1. The temperature of the γ peak of Ni/CeO2 was at 762.6°C, which is responsible for the bulk CeO2 support at the high reduction temperature (650–900°C)32. In this case, Ni/CeO2 was reduced by H2 at 500°C for an hour to convert NiO peaks in α and β forms to metallic Ni since the metallic Ni is more active for CO2 methanation.

Table 3 shows the H2 consumption over the Ni/CeO2 catalyst as determined by the H2-TPR pattern. The catalyst displayed a total H2 consumption of 2.836 mmol/g, with the greatest amount of H2 consumption (2.090 mmol/g) occurring in the major β peak. To compare the actual amount of H2 consumption of the Ni/CeO2 catalyst with the theory, the theoretical H2 consumption can be computed from NiO at 1.755 mmol/g of 10% (mass) of Ni. It was found that the actual amount of H2 in the Ni/CeO2 catalyst was higher than the theoretical amount. This was because of the H2 spillover effect, which occurs when CeO2 support in the γ region is also reduced during the H2-reduction step33.

The oxygen vacancy of the Ni/CeO2 catalyst was examined using Raman characterization. Since oxygen vacancies provide active sites for CO2 activation, they have the potential to improve the performance of CO2 methanation34. Oxygen vacancy content was determined by the ratio between the peak intensities of the D and F2g modes, as seen in Fig. 6b and Table 4. The F2g Raman activation mode of CeO2 was detected by the peaks at 454 and 456 cm-1, while the D mode of stretching vibration from the defect site was observed at 554 cm-135. It can be seen that after the H2-reduction process, the ID/IF2g ratio of Ni/CeO2 slightly increased, from 0.47 to 0.48. The reason for this could be that oxygen vacancies were abundant in the structures formed by NiO and CeO2 nanocrystals even prior to reduction. The finding was consistent with the results of the previous study36. Furthermore, the H2-TPR result in Fig. 6a demonstrated a strong interaction between the Ni and the CeO2 support, resulting in a high oxygen vacancy concentration of the catalyst37.

The surface roughness of the samples (Untreated Al spiral, Activated Al spiral, and Spiral-structured Ni/CeO2 catalysts)

The AFM technique was used to identify the topographical change of the Al spiral after the surface treatments and catalyst coating, as shown in Fig. 7. Each sample was randomly selected and measured to compare the surface roughness information. The surface of untreated Al spiral without chemical treatment showed slit patterns, with a depth ranging from 250-320 nm. After chemical etching, the surface of the Al spiral became corroded, causing it to lose its pattern and develop an irregular roughness instead. Chemical corrosion also removed the shine from the Al spiral, confirmed by the digital photos in Fig. 7.

In comparison to the untreated Al spiral substrate, the depth of the etched surface increased by 3–4 times (from 700 to 1,250 nm), improving the surface area accessible for the catalyst coating. Following Ni catalyst coating, the surface of the coated Al spiral remained inconsistent in height, ranging from 220 to 560 nm. However, it should be noted that the catalyst was strongly coated and adhered to the Al spiral surface due to its surface roughness. This promotes the strength of the spiral-structured Ni/CeO2 catalyst as well as increases the surface area, enhancing the catalytic activities of CO2 methanation.

CO2 methanation

The influence of temperatures over gradient-coated spiral-structured Ni/CeO2 catalysts in a single-passed reactor

Figure 8 shows the CO2 methanation performance, CO2 conversion, product selectivity, carbon balance, and temperature profile of gradient-coated spiral-structured Ni/CeO2 catalysts in a single-passed reactor. The reaction was performed at 200-500°C with a reactant feed flow rate of 100 ml/min. During CO2 methanation, the spiral catalysts recorded temperatures from front side to back side of the catalyst position, including 3 cm before the front side catalyst.

Figure 8a and 8b show that the CO2 conversion and CH4 selectivity, respectively, decreased in the 400–500°C range because of thermodynamic limitations of the methanation reaction, which can occur at high temperatures and create unwanted products like CO38. In order to determine the catalytic activity of CO2 methanation, reaction temperatures between 200 and 350°C were considered. The gradient-coated spiral-structured Ni/CeO2 catalysts in a single-passed reactor achieved the best catalytic performance for CO2 methanation at a temperature of 350°C, 96.4% CO2 conversion, and 99.9% CH4 selectivity.

The temperature of the inlet gas before reaching the spiral catalyst is close to the set value; however, when the reactant feed (CO2/H2) was introduced to the thick-coated front spiral catalyst (F), the temperature slightly rises because CO2 methanation is an exothermic reaction. The gas then passes to the thinner-coated spiral catalyst behind (B), where the temperature gradually decreases, as presented in Fig. 8d. This is due to the fact that the swirling flow enhanced convective heat transfer, which increases the efficiency of CO2 methanation by potentially reducing hotspots that can cause catalyst deactivation39. Spiral-shaped catalysts also demonstrated low pressure drop values between 0.02 and 0.07 mbar, which indicates that the spiral form encourages efficient gas flow. According to the temperature effect study, the carbon balance in Fig. 8c was within a reasonable range of 94–97%.

Aside from the spiral structure and gradient coating of the catalyst, there are other reasons why the gradient-coated spiral-structured Ni/CeO2 catalyst exhibits high performance of CO2 methanation. One of the reasons is that even after H2 reduction, the catalyst (reduced form) retains small Ni crystallite sizes of 28.3 nm, as shown in Table 1, thus improving CO2 methanation performance25. A further reason is the presence of oxygen vacancies (0.48 of ID/IF2g), as indicated in Raman spectra in Fig. 6b and Table 4, which enhances CH4 production by acting as active sites for CO2 adsorption and activation34, thereby encouraging CO2 methanation. Another reason is that the catalyst has a rough surface, as illustrated in Fig. 7c, which increases surface area of active sites, promoting CO2 methanation.

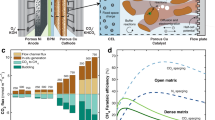

Comparison of catalytic performance between a single-passed and a triple-passed reactor at different flow rates

Figure 9 and Table 5 provide a comparison of the catalytic performance between a single-passed and triple-passed reactor over a spiral shape with a gradient-coated Ni/CeO2 catalyst at flow rates ranging from 100 ml/min to 3000 ml/min at a set temperature of 350°C. Relevant insights, such as pressure drop (PD), reaction rate (rm), and temperature profile, were also observed. As mentioned in Fig. 8, a gradient-coated spiral catalyst in a single-passed reactor presented excellent catalytic activity (96.4% CO2 conversion, and 99.9% CH4 selectivity) under a feed flow rate of 100 ml/min at 350°C. However, when operating a single reactor at high flow rates, Fig. 9a showed that the CO2 conversion of a single passing reactor tended to decline as the flow rates increased. This was due to high flow rates during CO2 methanation over Ni/CeO2 catalysts with a spiral shape, which can shorten the duration that CO2 species spend on the catalyst surface39. As a result, high flow rates limit the interaction between CO2 molecules and active sites, which lowers conversion rates and causes CO intermediates. For example, when increasing the reactant flow rate by 10 times, from 100 to 1000 ml/min, CO2 conversion dropped from 96.4% to 78.3%, as did CH4 selectivity, from 99.9% to 98.5% (see Fig. 9b). Catalytic activity in a single-passed reactor showed the same tendency, further declining at higher flow rates (see Table 5). To lower the production of CO intermediate when operating at high flow rates, the steam produced by the CO2 methanation was eliminated in order to further shift the equilibrium towards complete conversion to CH440. To improve the efficiency of producing CH4 in this study, a method of steam trapping from the reaction between reactor stages was employed, with the reactant gas passing through three reactors in a series. In order to compare changes in catalytic performance when removing water, data on CO2 conversion and CH4 selectivity were recorded individually for each reactor in the triple-passed reactor, together with the overall pressure drop (see Fig. 9c) and temperature profiles. As seen in Eq. (1), when conducting CO2 methanation, the water is also produced together with CH4, and the presence of water vapor can hinder the catalytic process by blocking active sites on the catalyst surface41. By effectively trapping steam, the catalyst surface remains free from water vapor, allowing for better interaction between the reactants and the catalyst, thus improving the rm42. This is consistent with the findings shown in Fig. 9d and Table 5, when eliminating steam from gas products, the rm in a triple-passed reactor always increased following R3 > R2 > R1 at all flow rates (R1, R2, and R3 represent gradient-coated spiral Ni/CeO2 catalysts operated in the first, second, and third reactor tubes, respectively, for a triple-passed reactor). The catalytic efficiency of CO2 methanation and CH4 selectivity also showed the same trend, R3 > R2 > R1, as shown in Fig. 9a and Table 5, since the effectiveness of steam removal. Sayed et al.42 confirmed that eliminating steam can cause the Sabatier reaction’s thermodynamic equilibrium to move to the product side, increasing the conversion of CO2.

The CO2 methanation performance of gradient-coated spiral-structured Ni/CeO2 catalysts were investigated in single-passed and triple-passed reactors at a set temperature of 350°C, with flow rates varying from 100 to 3000 ml/min as following: (a) CO2 conversion, (b) Product selectivity, (c) Pressure drop, (d) rm, and temperature profiles of (e) Single-passed and (f) Triple-passed reactors.

When comparing the efficiency of catalytic performances between single-passed and triple-passing, it was found that at a low feed flow rate (100 ml/min), both types of these two configurations have insignificant differences in catalytic efficiency for CO2 conversion (96.4% for S, 98.5% for R3) and CH4 selectivity (99.9% for both S and R3), as shown in Table 5. Furthermore, the temperature profiles of a single-passed and triple-passed reactors are not significantly different at a flow rate of 100 ml/min, as the maximum temperature of spiral catalysts in a single-passed reactor was 364°C, while that of a triple-passed reactor was 372°C.

When CO2 methanation catalytic activity is operated at higher flow rates (500-3000 ml/min), the temperature profiles of single-passed and triple-passed reactors showed that the thick-coated spiral catalyst at the front side has higher temperatures due to more intense exothermic reactions, compared to the spiral catalyst at the back side (see Table 5). The results of the temperature profile are consistent with previous research, as Najari et al.43 used kinetic models to study the impact of in situ water removal from a methanation reactor. It was demonstrated that eliminating water on-site enhanced CO2 conversion efficiency; however, this also raises the possibility of hotspots forming within the reactor, which might potentially affect the performance of the catalyst. The heat generated from the front catalyst was carried to the back spiral catalyst by swirling flow, leading to heat convection (see Fig. 9e and 9f). This helped reduce hotspots on the catalysts. Apparently, the temperature profile of a triple-passed reactor was much higher than that of a single-passed reactor. This is due to the exothermic reaction caused by CO2 methanation in a triple-passed reactor, which is placed side by side in the furnace and promotes a significantly greater temperature than a single reactor at all flow rates. For example, at 3000 ml/min, the maximum temperature of spiral catalysts in a single reactor was 400°C, while that of a triple-passed reactor was up to 499°C. Even operating CO2 methanation at high flow rates can cause high temperatures. A triple-passed reactor can achieve a CO2 conversion efficiency of up to 83.4% with CH4 selectivity at 94.9%, whereas a single-passed reactor achieved 64% with CH4 selectivity of 87.4%. This is because steam trapping via triple-passing promotes a further shift in equilibrium towards increased CH4 production and eliminates the issue of insufficient residence time.

It is worth noting that the CO2 conversion and CH4 selectivity in R1 of a triple-passed reactor are lower than those in a single-passed reactor, while they should be similar. This is due to the fact that R1 was surrounded by higher temperatures. As mentioned in Fig. 8, high temperatures can cause RWGS (Eq. (2)), reducing CO2 conversion but promoting CO selectivity. In addition to the high temperature, there is also a pressure drop occurring in the triple-passed reactor that causes R1 to have less catalytic performance than a single reactor. The triple-passed reactor has a larger pressure drop since the feed gas passes through three reactors in series. Meanwhile, a single reactor’s pressure drop progressively rises as the feed flow rate increases as it operates with an open-ended reactor. Table 5 shows that at high feed flow rates between 500 and 3000 ml/min, the rm of R1 in a triple-passed reactor is always slower than the rm of a single reactor because of the pressure drop effect in the experimental system. Despite having a higher total pressure drop, the triple-passed reactor demonstrated higher catalytic activity than a single reactor due to improved water removal effectiveness and the elimination of insufficient residence time.

Investigation of spent gradient-coated spiral-structured Ni/CeO2 catalysts after CO2 methanation

Figure 10 presents XRD pattern of spent gradient-coated spiral-structured Ni/CeO2 catalysts obtained from a single-passed reactor and a triple-passed reactor after conducting CO2 methanation. These spent catalysts were obtained from operating with CO2/H2 (1/4) feed flow rates from 100 to 3000 ml/min at 350°C. It should be mentioned that the thick-coated front spiral catalyst (F) from the single-passed and triple-passed reactors was chosen to represent the spent catalyst for each reactor. Regarding the triple-passed reactor, R1, R2, and R3 represent gradient-coated spiral Ni/CeO2 catalysts operated in the first, second, and third reactor tubes, respectively. The XRD pattern findings indicates no significant phase change in the CeO2 support structure under reaction conditions, as the CeO2 peaks remain prominent and stable across all conditions. The CeO2 crystallite sizes for all spent catalysts are within the range of 9.1–9.4 nm, but they are a bit smaller than that of the reduced catalyst (9.9 nm), as seen in Table 6. This is due to the thermal stability of CeO244, maintaining its crystallite sizes and preventing collapse of the lattice during CO2 methanation.

Prior to H2 reduction, the calcined Ni/CeO2 catalyst exhibits diffraction characteristic NiO peaks. However, NiO peak is reduced by H2 to form metallic Ni after H2 reduction, as no diffraction characteristic peaks are observed in the reduced Ni/CeO2 catalyst, seen in XRD results in Fig. 3. Apparently, the NiO peak at 28.5° of 2θ appeared again in all spent Ni/CeO2 catalysts after conducting CO2 methanation (see Fig. 10). This is because CO2 methanation produces water as a byproduct at high temperatures, water can oxidize metallic Ni to NiO, leading to the appearance of NiO peak in the post-reaction. This oxidation process can affect the catalyst’s performance, as NiO is less active in CO2 methanation compared to metallic Ni45. However, Table 6 shows that all spent catalysts of both single-passed and triple-passed reactors displayed NiO crystallite sizes at the range between 12.0 and 13.9 nm, which are not that large if compared to that of the calcined Ni/CeO2 (21.6 nm). To compare metallic Ni crystallite sizes of spent catalysts after CO2 methanation, it was found that Ni crystallite sizes from a triple-passed reactor (32.0 nm for spent-R1 and 33.4 nm for spent-R3) are greater than those from a single-passed reactor (29.0 nm), as seen in Table 6. This is due to Ni sintering at high temperatures, especially in the triple-passed reactor (see temperature profiles in Fig. 9e, f). When conducting CO2 methanation at the set temperature of 350°C, the actual temperatures are much higher than that set temperature as CO2 methanation is an exothermic reaction.

Figure 11a, b presents N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms, and pore size distributions of pristine CeO2 and Ni/CeO2 catalysts (calcined and reduced forms), together with spent-R1 Ni/CeO2. To compare the porosity of spent Ni/CeO2 with that of calcined and reduced forms, it should be noted that after CO2 methanation (at feed flow rates of CO2/H2 (1/4) from 100 to 3000 ml/min at 350°C), the thick-coated front spiral catalyst (F) from the first reactor tube in a triple-passed reactor was selected to represent the spent Ni/CeO2 catalyst in this study for Fig. 11.

(a) N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms, and (b) pore size distributions of pristine CeO2 and Ni/CeO2 catalysts in different forms (calcined and reduced forms), compared with spent-R1 Ni/CeO2 catalyst after performing CO2 methanation in triple-passed reactor (CO2/H2 (1/4) feed flow rates ranging from 100 to 3000 ml/min at 350°C).

As mentioned earlier in Fig. 5 and Table 2, The N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms of pristine CeO2 have a higher adsorption capacity than those of calcined and reduced Ni/CeO2 because adding Ni to pristine CeO2 may change the pore structure and SBET, leading to lower N2 adsorption capacity. Similarly, Fig. 11a shows that the isotherm of the spent Ni/CeO2 catalyst shows the lowest adsorption capacity, with the lowest SBET at 69.24 m2/g, (see Table 7). The significant loss of adsorption capacity and SBET can be attributed to sintering of Ni particles and carbon deposition during the CO₂ methanation when operating at high flow rates. Figure 11b shows that the spent Ni/CeO2 catalyst has a significantly larger average pore size of 8.5 nm when compared to other Ni/CeO2 forms. This reveals structural damage, which could be caused by Ni particle sintering, pore collapse, or carbon formation during CO2 methanation8.

Conclusion

The gradient coating approach was effectively used for fabricating spiral-structured Ni/CeO2 catalysts. The gradient coating transferred heat energy from a thick-coated front catalyst to a thinner-coated back catalyst, reducing hotspots as well as improving mass transfer through swirling flow. Single-passed and triple-passed operations were used to compare the catalytic performance of gradient-coated spiral-structured Ni/CeO2 catalysts with and without steam trapping. When operating at a low input flow rate (100 ml/min), a triple-passed reactor achieved slightly better CO2 conversion efficiency of 98.5% and CH4 selectivity of 99.9% than a single-passed reactor, which showed 96.4% CO₂ conversion and 99.9% CH₄ selectivity, respectively. It should be noted that both types of these two configurations exhibited insignificantly different catalytic performances. This was due to the fact that a low flow rate produced similar temperature profiles, a small amount of pressure drop, and no residence time limits. On the other hand, CO2 methanation is carried out at higher flow rates (500-3000 ml/min), and a triple-passed reactor performed better in terms of CO2 conversion and CH4 selectivity compared to a single-passed reactor. For instance, at 3000 ml/min, a triple-passed reactor can reach up to 83.4% CO2 conversion efficiency along with 94.9% CH4 selectivity, while a single-passed reactor only achieved 64% CO2 conversion with 87.4% CH4 selectivity. Increased CO2 conversion and CH4 selectivity are results of effectively trapping steam in a triple-passed reactor, which keeps the catalyst surface free from water vapor and allows for more contact between the reactants and the catalyst. A triple-passed reactor with steam trapping at high flow rates not only eliminates the insufficient residence time but also promotes a further shift in equilibrium toward increased CH4 production.

Data availability

All data related to the finding of this study are accessible upon request from the corresponding author Sakhon Ratchahat.

References

Asri, M. E., Yusak, S. & Norzahir. A short review on carbon dioxide (CO2) methanation process. Materials Today: Proceedings 31, 394–397 (2020).

Stangeland, K., Kalai, D., Li, H. & Yu, Z. CO2 methanation: The effect of catalysts and reaction conditions. Energy Procedia 105, 2022–2027 (2017).

Karelovic, A. & Ruiz, P. Mechanistic study of low temperature CO2 methanation over Rh/TiO2 catalysts. J. Cataly. 301, 141–153 (2013).

Xu, X. et al. Facile Cr3+-doping strategy dramatically promoting Ru/CeO2 for low-temperature CO2 methanation: Unraveling the roles of surface oxygen vacancies and hydroxyl groups. ACS Cataly. 11, 5762–5775 (2021).

Kim, H. Y., Lee, H. M. & Park, J.-N. Bifunctional mechanism of CO2 methanation on Pd-MgO/SiO2 Catalyst: Independent roles of MgO and Pd on CO2 methanation. J. Phys. Chem. C 114, 7128–7131 (2010).

González-Rangulan, V. V. et al. CO2 Methanation over nickel catalysts: Support effects investigated through specific activity and operando IR spectroscopy measurements. Catalysts 13 (2023).

Ye, R.-P. et al. Engineering Ni/SiO2 catalysts for enhanced CO2 methanation. Fuel 285, 119151 (2021).

Mebrahtu, C. et al. in Studies in Surface Science and Catalysis Vol. 178 (eds Stefania Albonetti, Siglinda Perathoner, & Elsje Alessandra Quadrelli) 85–103 (Elsevier, 2019).

Lin, J. et al. Enhanced low-temperature performance of CO2 methanation over mesoporous Ni/Al2O3-ZrO2 catalysts. Appl. Cataly. B Environ. 243, 262–272 (2019).

Wang, F. et al. Active site dependent reaction mechanism over Ru/CeO2 catalyst toward CO2 methanation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 6298–6305 (2016).

Rodríguez, S. L. et al. Effect of Pr in CO2 methanation Ru/CeO2 catalysts. J. Phys. Chem. C 125, 12038–12049 (2021).

Wu, Y. et al. Ni nanocatalysts supported on mesoporous Al2O3–CeO2 for CO2 methanation at low temperature. RSC Adv. 10, 2067–2072 (2020).

Sun, D. & Simakov, D. Thermal management of a Sabatier reactor for CO2 conversion into CH4 Simulation-based analysis. J. CO2 Utilization 21, 368–382 (2017).

Fukuhara, C., Hayakawa, K., Suzuki, Y., Kawasaki, W. & Watanabe, R. A novel nickel-based structured catalyst for CO2 methanation: A honeycomb-type Ni/CeO2 catalyst to transform greenhouse gas into useful resources. Appl. Cataly. A General 532, 12–18 (2017).

Ratchahat, S. et al. Development of a powerful CO2 methanation process using a structured Ni/CeO2 catalyst. J. CO2 Utilization 24, 210–219 (2018).

Fukuhara, C., Ratchahat, S., Kamiyama, A., Sudoh, M. & Watanabe, R. Auto-methanation performance of structured Ni-type catalyst for CO2 transformation. Chem. Lett. 48, 441–444 (2019).

Jomjaree, T. et al. Catalytic performance of Ni catalysts supported on CeO2 with different morphologies for low-temperature CO2 methanation. Catal. Today 375, 234–244 (2021).

Rui, N. et al. Highly active Ni/CeO2 catalyst for CO2 methanation: Preparation and characterization. Appl. Cataly. B Environ. 282, 119581 (2021).

Chen, Z., Ma, Z., Song, J., Wang, L. & Shao, G. A novel approach for the preparation of Ni–CeO2 composite cathodes with enhanced electrocatalytic activity. RSC Adv. 6, 60806–60814 (2016).

Marconi, E., Tuti, S. & Luisetto, I. Structure-sensitivity of CO2 methanation over nanostructured Ni supported on CeO2 nanorods. Catalysts 9 (2019).

Bahtiar, Z., Windarti, T. & Hudiyanti, D. The effect of calcination temperature on the characteristics of CeO2 synthesized using the precipitation method. Jurnal Kimia Sains dan Aplikasi 27, 226–231 (2024).

Shan, W., Luo, M., Ying, P., Shen, W. & Li, C. Reduction property and catalytic activity of Ce1−XNiXO2 mixed oxide catalysts for CH4 oxidation. Appl. Cataly. A General 246, 1–9 (2003).

Ruckenstein, E. & Pulvermacher, B. Growth kinetics and the size distributions of supported metal crystallites. J. Cataly. 29, 224–245 (1973).

Wynblatt, P. & Gjostein, N. A. Particle growth in model supported metal catalysts—I. Theory. Acta Metallurgica 24, 1165–1174 (1976).

Liu, J. et al. Enhanced low-temperature activity of CO2 methanation over highly-dispersed Ni/TiO2 catalyst. Cataly. Sci. Technol. 3, 2627–2633 (2013).

Wang, L. et al. Three-Dimensional mesoporous Ni-CeO2 catalysts with Ni embedded in the pore walls for CO2 methanation. Catalysts 10 (2020).

Parra-Marfil, A. et al. Modeling and experimental analysis of CO2 methanation reaction using Ni/CeO2 monolithic catalyst. Environ. Sci. Poll. Res. 31, 32766–32783 (2024).

Horváth, A. et al. Influence of 0.25% indium addition to Ni/CeO2 catalysts for dry reforming of methane. Catalysts 14 (2024).

Romero-Núñez, A. & Díaz, G. High oxygen storage capacity and enhanced catalytic performance of NiO/NixCe1−xO2−δ nanorods: Synergy between Ni-doping and 1D morphology. RSC Adv. 5, 54571–54579 (2015).

Ahasan, M. R., Hossain, M. M., Barlow, Z., Ding, X. & Wang, R. Low-temperature plasma-assisted catalytic dry reforming of methane over CeO2 nanorod-supported NiO catalysts in a dielectric barrier discharge reactor. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 15, 44984–44995 (2023).

Sun, C., Beaunier, P., La Parola, V., Liotta, L. F. & Da Costa, P. Ni/CeO2 nanoparticles promoted by yttrium doping as catalysts for CO2 methanation. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 3, 12355–12368 (2020).

Wang, L., Liu, H., Liu, Y., Chen, Y. & Yang, S. Influence of preparation method on performance of Ni-CeO2 catalysts for reverse water-gas shift reaction. J. Rare Earths 31, 559–564 (2013).

Sharma, V., Crozier, P. A., Sharma, R. & Adams, J. B. Direct observation of hydrogen spillover in Ni-loaded Pr-doped ceria. Cataly. Today 180, 2–8 (2012).

Hussain, I. et al. A review of the indispensable role of oxygen vacancies for enhanced CO2 methanation activity over CeO2-based catalysts: Uncovering, influencing, and tuning strategies. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 48, 24663–24696 (2023).

Zhang, Y., Zhang, T., Wang, F., Zhu, Q. & Liu, Q. Ni/CeO2 catalysts for low-temperature CO2 methanation: Identifying effect of support morphology and oxygen vacancy. Greenhouse Gases Sci. Technol. 11, 1222–1233 (2021).

Zhang, Y., Ye, F. & Li, W.-D.Z. Self-assembled two-dimensional NiO/CeO2 heterostructure rich in oxygen vacancies as efficient bifunctional electrocatalyst for alkaline hydrogen evolution and oxygen evolution. Chem. A Eur. J. 27, 3766–3771 (2021).

Li, X. et al. Strong metal-support interactions of Ni-CeO2 effectively improve the performance of a molten hydroxide direct carbon fuel cell. ACS Omega 7, 24646–24655 (2022).

Yeo, C.-E. et al. Optimization of operating conditions for CO2 methanation process using design of experiments. Energies 14 (2021).

Hossain, M. S., Akama, H., Verma, P., Watanabe, R. & Fukuhara, C. Effect of twist angle in spiral-type Ru/CeO2 catalysts on CO2 auto-methanation performance. J. Chem. Eng. Jpn. 56, 2182628 (2023).

Canu, P. & Pagin, M. Biogas upgrading by 2-steps methanation of its CO2 – Thermodynamics analysis. J. CO2 Utilization 63, 102123 (2022).

Sirigina, D. S. S. S., Goel, A. & Nazir, S. M. Process concepts and analysis for co-removing methane and carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. Sci. Rep. 13, 17290 (2023).

Hashemi, S. E., Lien, K. M., Hillestad, M., Schnell, S. K. & Austbø, B. Thermodynamic insight in design of methanation reactor with water removal considering nexus between CO2 conversion and irreversibilities. Energies 14 (2021).

Najari, S., Gróf, G. & Saeidi, S. Enhancement of hydrogenation of CO2 to hydrocarbons via In-Situ water removal. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 44, 24759–24781 (2019).

Yi, L. et al. The regulatory mechanisms of cerium oxide nanoparticles in oxidative stress and emerging applications in refractory wound care. Frontiers in Pharmacology 15 (2024).

Wasnik, C. G., Nakamura, M., Shimada, T., Machida, H. & Norinaga, K. CO2 methanation over low-loaded Ni-M, Ru-M (M = Co, Mn) catalysts supported on CeO2 and SiC. Carbon Resources Conversion, 100241 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This research has received funding support from the NSRF via the Program Management Unit for Human Resources & Institutional Development, Research and Innovation [grant number B16F640164].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.S.: Investigation, Methodology, Data curation, and Writing- Original draft preparation. A.S.: Resources. W. K.: Resources. P. K.: Funding acquisition and Visualization. S. A.: Resources and Visualization. C.F. : Resources and Visualization. S.R. : Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Visualization, Data curation, Supervision, and Writing- Reviewing and Editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Suriya, P., Srifa, A., Koo-Amornpattana, W. et al. A novel process of triple-passed CO2 methanation over gradient-coated spiral-structured Ni/CeO2 catalysts. Sci Rep 15, 9984 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-94262-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-94262-0

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Oxide-Type Materials for Catalytic CO2 Methanation: Recent Advances and Future Perspectives

Korean Journal of Chemical Engineering (2025)