Abstract

In the past, all the cloaks based on transformation optics or scattering cancellation posed some insufficiencies, for example, only two-dimensional concealment in experiments for the transformation-optics-based cloak and custom made and small hidden objects for scattering cancellation. Therefore, in this work, we proposed a spherical reciprocal cloak composed of shell-based dielectric metamaterials that could be realized by sophisticated ceramic manufacturing procedure. Field distributions of the integrated reciprocal cloaks without and with multiple objects suggested that although some scattering fields appeared, yet, the normalized differences of the scattering cross section when hidden objects were put within the cloak were only 8.44% and 1.11% along θ and ϕ directions, and field distributions for the cloak without and with hidden objects revealed an average relative deviation of 7.2%, demonstrating the capability of the cloak to conceal multiple different objects. Furthermore, the design procedure of the reciprocal cloak was further simplified since the thicknesses of the shell played the major role in the performances of the cloak and were the same within the same regime according to the previous simulation results. Again, the simplified cloak demonstrated the normalized differences of the scattering cross section of 29.93% and 4.58% along θ and ϕ directions and an average relative deviation of 6.1%. We believe such design strategy could be extended to other transformation optics based optical devices such as concentrators, rotators, illusion devices, etc., and pave a route toward a practical three-dimensional concealment in the field of stealth technology.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Through the past score, theories and possible designs of invisibility cloaks have been well-established by the methods of scattering cancellation and transformation optics, respectively1,2,3,4,5,6,7. First, in terms of scattering cancellation, a mantle composed of different metal structures is wrapped around a hidden object8,9. The scattering field of the mantle and hidden object would cancel each other, resulting in concealment of hidden objects. Nevertheless, it could only hide an electric-small object and should be custom made for different hidden objects. On the other hand, transformation-optics-based invisibility cloaks could be categorized into three different types, including an internal cloak3,4,10, an external cloak2,11,12,13 and a reciprocal cloak6,7,14,15,16. The internal cloak could hide arbitrary multiple hidden objects, but the hidden objects lose their visions. Furthermore, the coordinate transformation of the internal cloak involves the origin, resulting in a singular point and limits their operating frequency into the single one. On the other hand, the external cloak employed the concept of scattering cancellation and used anti-objects to create a scattering field with the same magnitude, but opposite sign compared to the one from the hidden objects. The two cancelled each other. Since the objects are put outside the external cloak, the hidden objects could maintain their vision from the environment. Moreover, there also appears no singular points in the external cloak, thus promising a broadband operation. Still, due to their working principle of concealment, a custom-made external cloak cannot hide other arbitrary objects inevitably. In addition, the relative movement between the anti-objects and the hidden objects is also forbidden. Finally, the reciprocal cloak was proposed with the integrated advantages from both the internal and external cloaks. For example, the reciprocal cloak could hide arbitrary multiple objects while these objects could move freely with visions. Unfortunately, the coordination transformation of the reciprocal cloak also involved the origin, thus limiting its operating bandwidth.

On the other hand, besides the intrinsic theoretical limitation of the invisibility cloaks, practical design of the cloak by different metamaterials and their corresponding fabrication methods also posed some obstacles for the realization of the cloaks in experiments. For example, the first experimental internal cloak was demonstrated by arranging split ring resonators or metallic nanowires in a dielectric host to achieve spatially-varied permeability along the radial direction. Some other works employed dielectric metamaterials composed of glass3 or BST17 for the realization of the cloak. Besides, invisibility carpets were demonstrated by a hole/pillar array on a silicon chip within visible ranges18,19,20, holes in Teflon in the microwave regime21 and metasurfaces with spatially distributed phase profiles22,23,24. On the other hand, there appears few literatures discussing experimental realization of the external cloak since the cloak possessed spatially varied negative refractive indices; still, Fang et al. proposed an external cloak with illusion optics by lumped elements networks including resistors, capacitors and inductors11. Finally, as for the reciprocal cloaks, continuous dielectric rings were designed to approach a cylindrical reciprocal cloak6,7. Overall, one can only manipulate the constitutive parameters of metallic metamaterials along a single direction. Next, hollow holes in dielectric material are suitable only for the design of the carpet cloak and sensitive to the incident angle. Meanwhile, metasurfaces also possessed similar drawbacks that the phase profiles of the metasurfaces are in accordance with incident angles. Finally, the lumped element could only be used in microwave regime, limiting the practical applications of the invisibility cloak. Therefore, it is the dielectric metamaterial, which could manipulate the three-dimensional constitutive parameters at will, the most promising candidate for the realization of the three-dimensional reciprocal cloak. Yet, the discrete dielectric metamaterial would impede the demonstration of the cloak due to the manual arrangement error. Furthermore, so far, there appears no practical and experimentally realizable three-dimensional reciprocal cloak25,26,27,28,29. For example, in Ref.25,27,28,29, the authors only provided theoretical calculations of the cloak without providing experimentally feasible design of the cloak. On the other hand, in Ref.26, the author provided a method to realization of the cloak by two alternating dielectrics which presented a difficult challenge for fabrication; therefore, in this work, we would like employ shell-based dielectric metamaterials to assemble a 3D reciprocal cloak.

Design and simulation of reciprocal cloaks

To design an experimentally realizable spherical reciprocal cloak, first of all, we distinguished three different regimes of the spherical reciprocal cloak including the hidden area (area I), the complementary area (area II) and the internal-cloak-like area (area III) with radii of R1, R2 and R3, respectively, as shown in Fig. 1a and b and would like to determine their spatially varied anisotropic constitutive parameters in the area II and III, (i.e., \(\varepsilon_{r}^{II}\), \(\varepsilon_{\theta }^{II}\), \(\mu_{r}^{II}\), \(\mu_{\theta }^{II}\), \(\varepsilon_{\phi }^{II}\) and \(\mu_{\phi }^{II}\) and \(\varepsilon_{r}^{III}\), \(\varepsilon_{\theta }^{III}\), \(\mu_{r}^{III}\), \(\mu_{\theta }^{III}\), \(\varepsilon_{\phi }^{III}\) and \(\mu_{\phi }^{III}\)), and the corresponding formulas were shown below25,26,27,28.

in which,

(a, b) Simulated schemes of the cloak with three areas including the hidden area, the complementary area and the internal cloak like area. The corresponding radii of the three areas were R1, R2 and R3. (c, e) Perspective and (d, f) side views of the field distributions of a 12 layered cloak (c, d) without and (e, f) with hidden objects, i.e., a silicon cuboid and a gold ellipsoid30.

After confirming the corresponding permittivity and permeability of the cloak, we employed shell-based dielectric metamaterials to realize such complicated constitutive parameters of the cloak. However, since the shell-based dielectric metamaterials themselves occupy the finite volume, thus, we should stratify the cloak into layers where the spatially varied permittivity/permeability should be constant. For the institutive thinking, the more layers, the better performances of the cloak. Yet, it is very difficult to design a cloak with infinitesimal layers. Therefore, we simulated the reciprocal cloak with a layer number of 9, 12 and 15 to balance the performance and fabrication difficulties of the cloak. Here, R1, R2 and R3 are arbitrarily chosen to be 0.5, 1 and 2 units for the radii of the hidden area, complementary area and internal-cloak-like area. Also, the field distributions of the 12-layered stratified cloak without and with hidden objects was plotted in Fig. 1c–f. Note that the objects we put inside the cloak are a silicon cuboid with a dielectric constant of 11.9 and a gold ellipsoid with conductivity of 4.56 × 107. From the field distributions, we could learn that there appear no significant scattering fields even the highly scattering objects are put inside the cloak. Also, fields could penetrate through the hidden area and arrive at the hidden objects, a characteristic of the reciprocal cloak. Furthermore, we employed an average relative deviation defined as the \(Avg\left( {\frac{{E_{z, stratified} - E_{z, pefect} }}{{E_{z, perfect} }}} \right)\) where Ez, stratified and Ez, perfect are the z-component electric fields for the stratified and perfect cloaks in the simulation to quantify the performance of the cloaks with different layers. As tabulated in Table 1, the 15 layered cloak revealed the smallest average relative deviation; yet the 12-layered one also showed an acceptable average relative deviation. When considering the fabrication procedure, the spacing to accommodate those shell-based dielectric metamaterials and alignment issues, we chose the 12-layred cloak as our design target.

Shell-based dielectric metamaterials

To design the corresponding shell-based metamaterials to construct a practical 3D invisible cloak, we arbitrarily chose R1, R2 and R3 equal to 48.646, 97.292 and 194.584 mm, respectively and the operating frequency was 8.81 GHz. Thus, the overall spacing of the cloak was equal to 194.584 minus 48.646, and this spacing was further divided into 24 layers when considering the dielectric metamaterials for both TE and TM modes. This resulted in a layer thickness of 6.08075 mm, and the inner and outer radius of each layer could be calculated by the following Eq. 3 and 4 below

where n is the nth layer of the 3D spherical cloak.

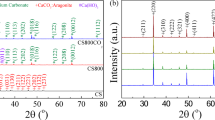

Furthermore, we used zirconia (ZrO2) with its high permittivity of 33 and low loss tangent of 0.0001 to design our shell-based dielectric metamaterials. It is worth mentioning that we believed the constitutive parameters, εr, εϕ and εθ, and μr, μϕ and μθ of a shell under spherical wave incidence could be regarded as the constitutive parameters of a cuboid, εx, εy and εz and μx, μy and μz under plane wave incidence in Cartesian coordinates once the cuboid was small compared to the incident wavelength6,7. Therefore, we just took out a small portion of the dielectric shell and regarded this small part of the shell as a cuboid as shown in Fig. 2. Thus, in simulation, along the azimuthal and polar directions, the cuboid should touch the boundaries to mimic a continuous shell, thus leaving only one-dimensional parameter to tune the corresponding permittivity and permeability of the cloak. In addition, along the radial direction, its length should not be larger than the layer spacing, i.e., 6.08075 mm in this simulation. Furthermore, every even/odd layer of the cloak should be simulated for TM incidence and TE incidence waves, respectively. Thus, three incident directions (i.e., r, θ and ϕ directions) are set to obtain the corresponding transmittance and reflectance spectra for each shell based dielectric metamaterial and the sophisticated retrieval method was employed to retrieve the corresponding εθ and μϕ (r-direction incidence), εϕ and μr (θ-direction incidence) and εr and μθ (ϕ-direction incidence) for TE modes and the corresponding εϕ and μθ (r-direction incidence), εr and μϕ (θ-direction incidence) and μθ and εr (ϕ-direction incidence) for TM modes. Note that the exact form of the spatially varied constitutive was achieved by shell-based metamaterials instead of just functional form, resulting in reduced backscattering compared to the ones used functional form7,29. Also, it is very difficult to approach the exact analytical values of Eq. 1 by the dielectric metamaterials. Thus, we set a range of the constitutive parameters for each layer predicted by substituting the inner and outer radii of each layer into Eq. 1. Once our retrieved constitutive parameters were within these ranges, we believed the parameters were acceptable. Still, we should verify the assembled spherical cloak in simulation. All the retrieved parameters were tabulated in Table 2 and after examining the retrieved constitutive parameters, there appeared only small deviations compared to the values predicted by Eq. 1. Such small deviations might result in stronger back scattering but still would not significantly influence the overall performance of the proposed cloak.

(a) Scheme of a shell-based dielectric metamaterial. (b) A rectangular portion of the shell for the retrieval of six constitutive parameters. Here, we could fine-tune the dimensional parameters of length a, width b and height c31.

To test the spherical reciprocal cloak composed of shell-based dielectric metamaterials, we assembled the simulated dielectric cuboids to 24-layered shells where the parameter “c” indicated the thickness of the shells, and the central radius of each shell could be determined by \(R_{c} = 48.646 + 6.08075 \times \left( {n - 0.5} \right)\) where n indicated the nth layer. Therefore, the inner and outer radius of each shell should be \(R_{i,o} = 48.646 + 6.08075 \times \left( {n - 0.5} \right) \mp c/2\). Meanwhile, the center of the shells for each layer is the same. In this way, we could assemble the total 24 layers of the dielectric shells into the spherical cloak. Then, the boundary conditions of the simulation along the x and y directions are perfect electric conductor and perfect magnetic conductor, respectively, and the boundary condition along the z direction should be open.

The corresponding simulated field distributions of the assembled spherical cloak were illustrated in Fig. 3 without (Fig. 3a) and with an electric larger object (a copper sphere, Fig. 3b) and two small objects (a silicon cuboid and a copper ellipsoid, Fig. 3c). From Fig. 3, there appear similar planar wavefronts before and after the cloak with a little bit scattering field. Also, the field could exist within hidden objects, enabling the vision of the hidden objects. To quantify the performance of the cloak, first of all, the corresponding scattering cross section were calculated in the far-field monitor and showed only 8.44% and 1.11% difference along θ and ϕ directions without and with the hidden object. Furthermore, the average relative deviations of the cloak with the hidden objects for the electric large object and two electric small objects were 7.2% and 4.6%, respectively. Note that when considering manufacturing tolerance of 0.01 mm for ceramic sintering, the potential fabrication method of the proposed cloak, the cloak showed almost the same field distribution with an average field deviation of 6.4% if we arbitrary varied the sizes of four dielectric shells within the cloak with fabrication tolerances of 0.02 mm; thus, the potential for experimental realization was guaranteed. Also, the proposed cloak could be operated under TE or TM incident plane waves due to the symmetrical properties of the spherical cloak. In addition, although in the design procedure, we focused on the frequency of 8.81 GHz, still, we would like to test the operating bandwidth of the cloak. All the average relative deviations at the different frequencies were tabulated in Table 3 and the criterion for the concealment of hidden objects was 10% of average relative deviation. Based on the criterion, the cloak could operate at the frequencies from 8.7 to 9.0 GHz with a bandwidth of 0.4 GHz. From the abovementioned quantification, we believed that our proposed spherical cloak composed of the shell-based metamaterials could conceal metal and dielectric once their sizes are smaller than the hidden area at a limited bandwidth instead of a single operating band.

Field distribution of the reciprocal cloak composed of overall 24 layered shell based dielectric metamaterials (a) without hidden objects, (b) with a copper sphere and (c) with a silicon cuboid and a copper ellipsoid31.

Taking a step further, when scrutinizing Table 2, we could realize that the ‘c’ parameters of the shell-based metamaterials were the same within the same regime and the ‘a’ and ‘b’ parameters played a minor role in the determination of the shell. Thus, we proposed a simplified method for the components of the spherical cloak that is to simulate one shell-based dielectric metamaterial for each regime and each mode. By doing so, we could reduce our total designed shell-based metamaterials from 72 to 4, significantly suppressing the simulation time for the design of the cloak. Furthermore, since the ‘a’ and ‘b’ were minor in the design procedure, thus any constitutive parameters regarding these two directions could be omitted. Therefore, we only need to retrieve εθ and μϕ for TE mode and μθ and εϕ for TM mode, respectively. To verify this idea, we designed another spherical cloak operating at a frequency of 4.33 GHz. The corresponding R1, R2 and R3 were 49.488, 98.976 and 197.952 mm, respectively. All the simulation setup of the shell-based metamaterials were the same and the ‘c’ parameter for each regime and each mode and the retrieved constitutive parameters were tabulated in Table 4.

The corresponding simulated field distribution of the assembled simplified cloak were illustrated in Fig. 4 without (Fig. 4a) and with an electric larger object (a copper sphere, Fig. 4b) and two small objects (a silicon cuboid and a gold sphere, Fig. 4c). From Fig. 4, planar wavefronts could be observed with several back- and forward-scattering fields before and after the cloak. Also, the field could exist within the hidden area, enabling the vision of the hidden objects. Still, when the different objects were put inside the cloak, the field distribution did not vary, guaranteeing the concealment of the hidden objects. To quantify the performance of the simplified cloak, the corresponding scattering cross section were calculated in the far-field monitor and showed only 29.94% and 4.58% difference along θ and ϕ directions without and with the hidden object. Furthermore, the average relative deviation of the cloak without and with the hidden objects were 6.1% and 2.9%, respectively, for the electric large object and two electric small objects. Again, we would like to test the operating bandwidth of the simplified cloak. All the average relative deviations of the proposed simplified spherical cloak at the different frequencies were tabulated in Table 5. Here, the criterion for the concealment of hidden objects was 7% of the average relative deviation, a higher criterion due to the lower operating frequency. Based on this criterion, the cloak could operate at the frequencies from 2.8 to 4.33 GHz with a bandwidth of 1.63 GHz. From the abovementioned quantification, we believed that the simplified cloak could also conceal metal and dielectric once their sizes are smaller than the hidden area at a limited bandwidth instead of a single operating band. To sum up, we tabulated the advantages and disadvantages in Table 6 and believed that our proposed spherical cloak revealed easier design and fabrication process compared to others. Finally, to conduct the experiment, we should first fabricate two semispherical shells for each layer and then assemble those shells into the proposed cloak. The two parallel metal plates supporting a plane wave excitation with a hole in the center for the detection probe is constructed. Note that the lower metal plate was put on a two-dimensional stepper. Therefore, we could map the field distribution outside the cloak.

Field distribution of the simplified reciprocal cloak composed of the shell-based dielectric metamaterials (a) without hidden objects, and (b) with an electric large object, a copper sphere and (c) two electric small objects, a silicon cuboid and a gold sphere31.

Conclusions

In this work, we have designed a spherical reciprocal cloak by 24-layered shell-based dielectric metamaterials. In simulation, the assembled cloak without hidden objects and with an electric large object and two electric small objects demonstrated an average relative deviation of 7.2% and 4.6%, respectively, verifying the concealment of the spherical cloak. Also, the bandwidth of the proposed cloak was 0.4 GHz. Furthermore, we proposed a simplified design procedure of the spherical reciprocal cloak and significantly reduced the simulation times. The simplified cloak without hidden object and with an electric large object and two electric small objects revealed an average relative deviation of 6.1 and 2.9%, respectively, consolidating the effectiveness of the simplified design procedure and concealment of the simplified cloak. The bandwidth of the simplified cloak was 1.64 GHz. We believe the proposed design strategy paves a route toward guidelines for future transformation optics-based devices.

Data availability

The data sets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Alù, A. & Engheta, N. Cloaking a sensor. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102 (2009).

Lai, Y., Chen, H., Zhang, Z.-Q. & Chan, C. Complementary media invisibility cloak that cloaks objects at a distance outside the cloaking shell. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 093901 (2009).

Semouchkina, E., Werner, D. H., Semouchkin, G. B. & Pantano, C. An infrared invisibility cloak composed of glass. Appl. Phys. Lett. 96, 233503 (2010).

Landy, N. & Smith, D. R. A full-parameter unidirectional metamaterial cloak for microwaves. Nat. Mater. 12, 25–28 (2013).

Schumann, M. F. et al. All-angle invisibility cloaking of contact fingers on solar cells by refractive free-form surfaces. Adv. Opt. Mater. 5, 1700164 (2017).

Lin, J.-H., Yen, T.-J. & Huang, T.-Y. Design of annulus-based dielectric metamaterial cloak with properties of illusion optics. J. Opt. 22, 085101 (2020).

Huang, T.-Y., Lin, J.-H., Lee, T. & Yen, T.-J. Experimentally approaching to reciprocal cloaks via annulus-dielectric-metamaterials. J. Opt. 21, 08LT01 (2019).

Chen, P.-Y., Monticone, F. & Alu, A. Suppressing the electromagnetic scattering with an helical mantle cloak. IEEE Antennas Wirel. Propag. Lett. 10, 1598–1601 (2011).

Fruhnert, M. et al. Tunable scattering cancellation cloak with plasmonic ellipsoids in the visible. Phys. Rev. B 93, 245127 (2016).

Luo, Y. et al. A rigorous analysis of plane-transformed invisibility cloaks. https://doi.org/10.1109/tap.2009.2027824.

Li, C., Liu, X., Liu, G., Li, F. & Fang, G. Experimental demonstration of illusion optics with “external cloaking” effects. Appl. Phys. Lett. 99, 084104 (2011).

Chen, H., Luo, X., Ma, H. & Chan, C. T. The anti-cloak. Opt. Express 16, 14603–14608 (2008).

Mei, J. S., Wu, Q. & Zhang, K. Complementary cloak based on conventional cloak with axial symmetrical cloaked region. Appl. Phys. A 108, 1001–1005 (2012).

Yang, J. J., Huang, M., Mao, F. C., Cai, G. H. & Lan, Y. Z. Electromagnetic reciprocal cloak with only axial material parameter spatially variant. Int. J. Antennas Propag. 2012, 1–9 (2012).

Yang, J. J., Huang, M., Yang, C. F. & Yu, J. Reciprocal invisibility cloak based on complementary media. Eur. Phys. J. D 61, 731–736 (2011).

Yang, J., Huang, M., Li, Y. L., Li, T. & Sun, J. Reciprocal invisible cloak with homogeneous metamaterials. Progress Electromagn. Res. M 21, 105–115 (2011).

Gaillot, D. P., Croënne, C., Zhang, F. & Lippens, D. Transformation optics for the full dielectric electromagnetic cloak and metal–dielectric planar hyperlens. N. J. Phys. 10, 115039 (2008).

Valentine, J., Li, J., Zentgraf, T., Bartal, G. & Zhang, X. An optical cloak made of dielectrics. Nat. Mater. 8, 568–571 (2009).

Chen, X. et al. Macroscopic invisibility cloaking of visible light. Nature Communications 2, 176 (2011).

Gabrielli, L. H., Cardenas, J., Poitras, C. B. & Lipson, M. Silicon nanostructure cloak operating at optical frequencies. Nat. Photonics https://doi.org/10.1038/nphoton.2009.117 (2009).

Wang, N., Ma, Y., Huang, R. & Ong, C. K. Far field free-space measurement of three dimensional hole—in—Teflon invisibility cloak. Opt. Express 21, 5941 (2013).

Yang, Y., Wang, H., Yu, F., Xu, Z. & Chen, H. A metasurface carpet cloak for electromagnetic, acoustic and water waves. Sci. Rep. 6, 20219 (2016).

Yang, Y. et al. Full-polarization 3D metasurface cloak with preserved amplitude and phase. Adv. Mater. 28, 6866–6871 (2016).

Jia, Y. et al. In situ customized illusion enabled by global metasurface reconstruction. Adv. Funct. Mater. 32, 2109331 (2022).

Schurig, D., Smith, D. R. & Pendry, J. B. Calculation of material properties and ray tracing in transformation media. Opt. Express 14, 9794–9804 (2006).

Qiu, C.-W., Hu, L., Xu, X. & Feng, Y. Spherical cloaking with homogeneous isotropic multilayered structures. Phys. Rev. E 79, 047602 (2009).

Castaldi, G., Gallina, I., Galdi, V., Alù, A. & Engheta, N. Analytical study of spherical cloak/anti-cloak interactions. Wave Motion 48, 455–467 (2011).

Xuan, Y. & Xu, X. Three-Dimensional Reciprocal Invisibility Cloak with Multilayered Structure. J. Microw., Optoelectron. Electromagn. Appl. 18, 184–195 (2019).

Schurig, D. et al. Metamaterial electromagnetic cloak at microwave frequencies. Science 314, 977–980 (2006).

COMSOL Multiphysics v.6.2. COMSOL AB. www.comsol.com.

CST Studio Suite v.2018. Dassault Systèmes. www.3ds.com.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the financial support from National Science and Technology Council (NSTC 113-2221-E-131-019) and from the Center for Plasma and Thin Film and Thin Film Technologies and Ming Chi University of Technology.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Tsung-Yu Huang conceived the project, Tsung-Yu Huang, Jing-Hao Huang and He-Jun Ren designed, simulated and measured the sample. Tsung-Yu Huang, Jing-Hao Huang and He-Jun Ren co-wrote the paper. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Huang, JH., Ren, HJ. & Huang, TY. A simplified approach to 3D spherical cloaking using shell based dielectric metamaterials. Sci Rep 15, 9427 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-94344-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-94344-z

This article is cited by

-

Optical waveguide as a dual band high sensitivity biosensor based on grating cavity structure

Optical and Quantum Electronics (2025)