Abstract

Species that rely on dens are integral to sustaining ecosystem balance, and gaining insight into their den selection patterns is essential for successful conservation efforts. The Indian Gray Wolf (Canis lupus pallipes) faces significant challenges in finding safe denning sites amidst India’s human-dominated landscapes. The survival of this species depends heavily on its ability to coexist with humans. As one of the oldest wolf lineages, they have evolved separately and adapted to the semi-arid landscapes of India. This study investigates den-site selection within a 64 km² area of the MWS, Jharkhand, India. Between 2022 and 2024, 18 active dens were identified and analysed against 40 random locations to assess the importance of habitat and anthropogenic variables in den-site selection. The results revealed that dens are typically found in areas with abundant Sal (Shorea robusta) trees, steep slopes, and increased shrub cover. This highlights the significance of the Sal tree, where its cultural association helps minimize disturbances, indirectly supporting wolf breeding habitats. This study emphasizes the need to understand the ecological requirements of the Indian Gray Wolf and incorporate traditional cultural practices into wildlife management strategies. By shedding light on den site selection in tribal landscapes, the study offers crucial insights for wildlife managers, enabling them to develop effective conservation plans that promote the survival of Indian wolves and foster coexistence with humans amid evolving environmental conditions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Large carnivores worldwide are experiencing a significant decline, primarily due to habitat destruction and deliberate persecution by humans1. Many predator species are now classified as vulnerable, endangered, or critically endangered, with more than 75% of their populations undergoing a downward trend2,3,4. Human-wildlife conflict is now the leading factor driving many large carnivore populations toward collapse1,5,6. Thankfully, many conservation efforts over the past century have led to the recovery of several carnivore species that were once on the verge of extinction7. Although extinction is primarily a demographic process influenced by changes in mortality and fertility rates that lead to a decline in population growth8. Consequently, the study of breeding sites, which directly contributes to understanding species demography, is crucial for the formulation of effective population management programs8.

The wolf population in India is in a critical state, with numbers even lower than that of tigers (Panthera tigris), estimated at around 3,100 individuals in the wild9,10. Extensive habitat loss due to human expansion and retaliatory killings have significantly contributed to the decline of wolf populations throughout their range10,11. Coexistence may be vital for the conservation of this species12, while co-adaptation is essential for promoting peaceful relations between humans and large carnivores13. Promoting coexistence requires managing the complex interactions between people and wildlife, as well as addressing the differing perspectives among human groups regarding wildlife issues14. In recent years, conservationists have employed various approaches to address coexistence challenges15,16, yet little is understood about this concept or how to effectively study it12.

Moreover, tribal traditions and cultural practices can play a pivotal role in understanding coexistence mechanisms and contribute to species conservation, such as that of the wolf. For centuries, indigenous communities in India have been integral to biodiversity conservation across various ecosystems, from rainforests to alpine and coastal habitats17. India’s long history of human settlement has introduced a variety of cultural and religious traditions, many of which involve the worship of nature and the preservation of sacred forests dedicated to deities or ancestral spirits18. Many tribes follow practices like totemism, which fosters the protection of biodiversity by revering certain species and habitats as sacred19. Such belief systems, which incorporate taboos and spiritual connections with the land, promote the conservation of flora and fauna, some of which are endangered or threatened20. Jharkhand, with its rich biodiversity and significant tribal population (26.3% of the state’s total)21, exemplifies this connection between indigenous cultures and conservation. The region’s tribal communities adhere to taboos that prevent the exploitation of natural resources, ensuring the regeneration and protection of forests and creating spaces for wildlife to thrive19,22. These traditions create disturbance-free zones that wildlife can utilize, indirectly supporting ecosystem stability and biodiversity19.

Wildlife managers throughout the wolf range, particularly in heavily populated nations such as India, encounter considerable difficulties in reducing human disturbances23,24,25. Interestingly, this is not the case in the Mahuadanr Wolf Sanctuary (hereafter MWS), where the Sal tree (Shorea robusta) dominates, and interestingly, the local tribal people, who worship the tree, strictly avoid entering the forest during winter until the Sal flowers begin to bloom19. Human disturbance at wolf dens and rendezvous sites continues to be a concern. However, the influence of cultural factors on wolves den site selection remains understudied and needs further exploration.

Additionally, den sites are a vital component of wolf ecology26, and gaining insights into how wolves select these locations is crucial for wildlife managers to make informed decisions about their management and conservation26. Dens are vital for the survival of wolf populations, serving as a limited resource for some groups27. Den sites provide shelter from severe weather and offer protection from predators26.The stable microclimate provided by dens is particularly important for the survival of young pups28,29. Another significant factor is the topography of canid den sites, which plays a role in predator avoidance26. It is essential to understand the topographical characteristics of den sites, as most pup mortality happens within the first six months of life29,30. The placement of dens affects the susceptibility of both pups and adult wolves to predators31.Topographical features, particularly slope, are considered “energy-expensive terrains” where movement incurs higher energy costs due to the effects of gravity, as compared to flat terrain32. In response to inclined surfaces, animals tend to adopt energy-efficient movement strategies, such as altering their speed, direction, and avoiding steeper slopes33. This behaviour allows wolves to access relatively safer areas by utilizing their long-term understanding of how competitors use the space. There is a lack of research dedicated to understanding the energy-efficient movement patterns of large carnivores in India, particularly concerning slope. This aspect is vital to denning ecology and could provide important insights into the factors influencing den site selection, especially regarding interspecific competition.

Our study focuses on the MWS in Jharkhand, India, which is recognized as one of the key wolf breeding sites in the country9,34. The MWS is situated in the Mahuadanr block of Latehar district, an area largely populated by tribal communities35.The cultural practices of the local tribes, particularly their avoidance of the Sal-dominated forests during winter—coinciding with the wolves’ breeding season—along with the area’s topographical features, lead us to hypothesize in two distinct directions.

-

1.

(H1) Wolves preferentially select den sites located in areas with challenging topographical features, which are energetically demanding for other predators to access. This selection behavior reduces the likelihood of encounters with co- predators, thereby increasing the survival chance of the wolves.

-

2

(H2) The Sal Forest serves as a refugia for wolf den sites as tribal people avoid entering these areas during winter, resulting in a disturbance free zone that enhances the suitability of the forest for denning.

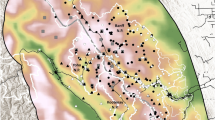

We tested both hypotheses independently using relevant variables and then combined them to assess their overall effect. This approach could provide novel and valuable insights for this region, as den site selection plays a critical role in the survival of both adult wolves and their young28,29,31,36. We expect that our findings will aid management and conservation efforts by pinpointing the locations and timing of wolf denning, facilitating more informed, data-driven decision-making (Fig. 1).

Results

Over the course of three breeding seasons (2022: 8 dens, 2023: 7 dens, 2024: 5 dens), a total of 18 wolf dens were identified within the study area (Fig. 2). Notably, no instances of multiple dens being utilized or den-shifting behaviour were observed throughout the duration of the study. All dens were situated in rock crevices and caves. Of these, The majority of dens (n = 9) had multiple opening points, with three opening being the most common configuration, while 5 dens had two entrance points, and 4 dens had a single entrance point. The average entrance diameter of the den openings was 1.05 m ± 0.10, ranging from 0.5 m to 2.1 m. The average slope of the den sites was 23.16° ± 2.18, with a range of 5.57° to 35.98°, and the average elevation was 747.28 m ± 50.13, ranging from 250 m to 1,110 m. The analysis of den site proximity to human settlements showed that the majority of dens (55.6%, n = 10) were located between 501 and 1000 m from the nearest human settlement. Additionally, 22.2% (n = 4) were found within 0 to 500 m, 16.7% (n = 3) were situated between 1001 and 1500 m, and only 5.6% (n = 1) were located between 1501 and 2000 m from human settlements. In terms of proximity to water sources, 38.9% (n = 7) of the dens were located within 501 to 1500 m from the nearest water source, while 27.8% (n = 5) were found between 201 and 500 m. Additionally, 22.2% (n = 4) of the dens were situated between 101 and 200 m, and 11.1% (n = 2) were located within 0 to 100 m of the nearest water source. All dens (n = 18) were located in habitats dominated by Sal trees, with an average of 6.94 ± 0.35 Sal trees per den site, ranging from 4 to 11 trees.

For hypothesis one, we used topographical and habitat-related variables, testing multiple combinations with the species ecology as the focus. Two models performed best, with ΔAIC values less than 2 (H1A and H1B, Table 1). The number of opening points (β = 1.10 ± SE 0.78), presence of shrub cover (β = 0.22 ± SE 0.07), and degree of slope (β = 0.23 ± SE 0.09) were positively associated with den site selection. However, entrance diameter was negatively associated (β = -1.6 ± SE 1.2), though this variable was not found to be statistically significant (Supplementary Information Figure. S3).

For hypothesis two, we utilized habitat and disturbance variables. Similar to the first hypothesis, two models performed best, with ΔAIC values less than 2 (H2A and H2B, Table 1). Sal abundance (β = 1.43 ± SE 0.52), shrub cover (β = 0.11 ± SE 0.06), and distance to human settlements (β = 0.002 ± SE 0.001) were positively associated with den site selection, while the relative disturbance index (β = -2.62 ± SE 1.59) showed a negative association. However, none of the variables were statistically significant except for Sal abundance (Supplementary Information Figure S4) (Figs. 3, 4 and 5).

Finally, we combined both hypotheses and tested the full model. The combination of Sal abundance, slope, and average shrub cover yielded the best fit, demonstrating strong explanatory power for wolf den site selection (P ≤ 0.05; Table 2). To further assess the model’s performance, A Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve was utilized (Fig. 6), plotting the true positive rate (sensitivity) against the false positive rate (1 - specificity) across various threshold values. The area under the curve (AUC) was calculated to be 0.98, reflecting excellent discriminatory ability. An AUC of 1.0 signifies perfect classification, whereas an AUC of 0.5 indicates no discriminatory power. With an AUC of 0.98, the model exhibited a strong capacity to differentiate between positive and negative cases, underscoring its robust predictive performance. In the top model, the beta coefficient values for Sal abundance, slope, and average shrub cover were 1.09 ± 0.10, 0.24 ± 0.10, and 0.16 ± 0.07, respectively (Fig. 7). Among these factors, Sal abundance emerged as the most critical determinant influencing wolf den site selection (Fig. 3). The model identified slope as the second most influential factor impacting the likelihood of den site selection (Fig. 4).The likelihood of choosing a den site increased with both Sal abundance and slope. Additionally, the percentage of average shrub cover was positively correlated with the likelihood of den site selection, further underscoring its importance in identifying suitable denning locations for wolves (Fig. 5).

Discussion

We studied the den site selection of Indian wolves (Canis lupus pallipes) in relation to topographical features and the indirect effects of traditional practices by nearby tribal communities on the Sal forest. Reproduction, particularly pup survival, plays a vital role in wolf population growth37. The choice of den sites and activities surrounding them significantly impact the reproductive success of wolf packs, as pup mortality is highest within the first six months of life30,38. Dens serve as central hubs within a wolf’s home range, playing a crucial role in vital activities such as feeding and breeding, both of which are fundamental to the species’ survival39,40. Human disturbance is a key factor influencing wolves to use multiple dens or engage in den-shifting behaviour41. However, in this study, we did not observe instances of multiple den use by wolves, underscoring the importance of relatively undisturbed areas as critical habitat for wolf denning sites.

Our results indicate a decrease in the number of confirmed wolf dens over the three breeding seasons (2022: 8 dens, 2023: 7 dens, 2024: 5 dens). However, it is important to note that our study focused solely on den site selection and did not assess the overall wolf population dynamics in the area. The observed decline could be influenced by several factors, including natural fluctuations in denning behaviour or potential undetected dens. Additionally, our survey methodology did not incorporate radio telemetry, which may have limited our ability to locate all existing dens. A dedicated study on wolf population status and movement patterns would be essential to better understand the underlying reasons for this trend.

Furthermore, our results suggest that most of the dens observed in our study had multiple openings, which is contrary to the findings of Khan et al. (2024)42 from Maharashtra, India. In their study, most dens were located in grasslands and were burrowed into the ground. In contrast, all the dens in our study area were located in rock caves, and no burrows were found to be occupied by wolves. This variation could potentially be attributed to the differences in habitat types between the two regions. Additionally, the absence of radio telemetry in our study may have limited the detection of certain den types, such as ground burrows. These findings underscore the importance of regional context and methodology in understanding wolf denning behaviour.

However, many species show a preference for rocky refugia, which are considered to provide advantages over burrows. Unlike burrows, which are susceptible to flooding and structural damage43, rocky refugia remain dry, retain their structure, and offer a more stable microenvironment44.

The choice of den types, whether burrows or rocky refugia, can vary regionally based on local environmental conditions32. Furthermore, Our results did not indicate significant spatio-temporal differences in den selection patterns, as dens were consistently located in rocky habitats across the study years. This suggests a strong preference for rocky terrain, likely due to its structural benefits such as protection from predators and minimal human disturbance32. While radio telemetry could provide finer-scale movement data, it is unlikely to drastically change our conclusions regarding den site selection, as wolves exhibit strong fidelity to specific habitat features for denning24,41,42. Additionally, direct field observations and habitat assessments supported our findings. However, to capture more nuanced spatial or temporal variations, future studies incorporating GPS tracking and long-term monitoring would be beneficial32,41.

These findings underscore the importance of regional context and methodology in understanding wolf denning behaviours. Additionally, the presence of multiple openings in dens is consistent with the observations made by Matteson74 in Montana. Additionally, we observed a negative association between opening diameters and active dens, indicating that smaller openings may facilitate easy escape for wolves while making it more difficult for larger predators to enter the den. Moreover, We reported that the majority of dens (55.6%, n = 10) were located between 501 and 1000 m from the nearest human settlement which in contrast with other studies conducted outside India45,46,47, wolf prefer to den away from it whereas our results shows contrast of it and we reported that the majority of dens (55.6%, n = 10) were located between 501 and 1000 m from the nearest human settlement, similar kind of result is found by Thiel et al., (1998) and Khan et al., (2024)42,48, , this could that disturbance is not the major issue in our study area as people strictly avoid entering the forest during this time because of their cultural believes and the domestic prey near the human habitation is available. Numerous studies have highlighted resource availability as the key factor affecting wolf reproductive success37. Additionally, 61% (n = 11) of dens were located within 500 m of a waterhole, a finding consistent with other studies41,42,49,50,51,52,53. This emphasizes the significance of water sources near den sites. Proximity to water reduces the distance adult wolves need to travel, thereby minimizing the time dens are left unattended while they hydrate. Additionally, the increased hydration needs of the breeding female during lactation likely contribute to this pattern54. Since canid milk is relatively diluted, lactating females require sufficient water intake to produce milk, making proximity to water a critical factor during this time41.

Wolves exhibit a hierarchical habitat selection process that varies across spatial and temporal scales27. While the influence of anthropogenic and habitat factors on den site selection has not been extensively documented for Indian wolves42, these aspects have been well studied in other wolf subspecies47,55. In our study, all identified dens were located in habitats dominated by Sal trees, with an average of 6.94 ± 0.35 Sal trees per site. Human presence, often described as the “super-predator,” can induce fear and avoidance behaviours even in large carnivores, leading to shifts in their behaviour to minimize risky encounters4,56. However, in this case, the results align with our initial hypothesis. This may be due to the cultural significance of Sal trees in the study area19. where they are revered and protected, resulting in minimal human intrusion into Sal patches. Consequently, these areas function as disturbance-free zones.

Initially, we tested both hypotheses separately, but the results were not as strong as expected. Therefore, we combined the hypotheses, and our top model showed that den site selection was influenced by Sal abundance, slope, and average shrub cover, all of which had a positive relationship with the probability of den site selection. As previously discussed, Sal trees hold cultural significance in the region, leading to reduced human disturbance in Sal-dominated areas. Slope emerged as a key topographical feature in our model, similar to findings in other studies32,57,58, supporting our second hypothesis. Steep slopes may deter larger predators, as the energy costs of reaching such areas would be prohibitive32. Additionally, average shrub cover emerged as an important factor, as dense vegetation around dens may provide concealment from potential predators, thereby enhancing the survival fitness of the species32,59. Our study on wolf (Canis lupus pallipes) den site selection reveals that both topographical features and anthropogenic influences, particularly traditional practices associated with Sal forests, play a significant role in shaping denning behaviour. We found that den site selection is positively influenced by Sal abundance, slope, and shrub cover. The cultural reverence for Sal trees by local tribal communities appears to create disturbance-free zones, allowing wolves to use these habitats without significant human interference. Additionally, steep slopes likely serve as natural barriers to larger predators, while dense shrub cover offers concealment, enhancing pup survival. Overall, our findings underscore the importance of culturally protected landscapes in wolf conservation and highlight the need to consider both ecological and cultural factors when managing wolf populations and their habitats. The interplay between traditional practices, topography, and habitat characteristics has created an environment that supports the reproductive success and survival of wolves in the region. This research enhances our understanding of the factors influencing den site selection and offers valuable insights for the conservation of wolves in India.

Materials and methods

Study area

MWS, located in the Latehar district of Jharkhand, falls under the administrative jurisdiction of the Palamau Tiger Reserve (hereafter PTR) Circle35,60. It lies in the southern region of PTR, Jharkhand, India. Established in 1976 through a declaration by the Government of Bihar60, it holds the distinction of being India’s first and only wolf sanctuary61.

The sanctuary’s total forested area covers 63.256 km² (Fig. 1)60. It is distinguished by surrounding hill ranges with varying elevations, where the western hilltops have flat terrain at an elevation of 1,170 m35. The area’s isolated hills are located near valleys62, and the Burha River serves as the main waterway draining the Mahuadanr valley60. Its drainage flows from south to north, forming tributaries of the Son River62. The area experiences a humid subtropical climate characterized by three distinct seasons: a hot and dry summer, a cold winter, and a rainy monsoon62. The cold season generally spans from November to March, transitioning into summer from April to mid-June, with the monsoon season occurring between mid-June and mid-October62.The cup-shaped valley, surrounded by hills, results in an average annual rainfall of 1,300 mm, with around 90% of it occurring during the monsoon between June and October62. There are 25 villages located near the sanctuary, along with an additional 72 villages within its buffer zone, totalling around 14,000 households21,60. population in this area is predominantly tribal, with 78.68% belonging to Scheduled Tribes and 3.2% to Scheduled Castes21. The strong cultural ties of the tribal communities remain intact in this region, reflected in the prominent celebration of the Sarhul festival, during which the tribal population venerates the Sal tree as part of their cultural and religious practices19.

MWS boasts a rich biodiversity, encompassing a wide array of flora and fauna. The sanctuary’s flora includes species such as Aegle marmelos (Bael), Albizia lebbeck (Siris), Azadirachta indica (Neem), Buchanania lanzan (Pial), Diospyros melanoxylon (Kendua), Diospyros montana (Loharia), Ficus racemosa (Dumur), Gmelina arborea (Gamar), Haldina cordifolia (Karam), Holarrhena pubescens (Kurchi), Mangifera indica (Mango), Madhuca latifolia (Mahua), Pterocarpus marsupium (Piasal), Schleichera oleosa (Kusum), Semecarpus anacardium (Bhela), Shorea robusta (Sal) as the dominant tree species, Terminalia arjuna (Arjun), Terminalia bellirica (Bahera), Terminalia chebula (Haritaki), Terminalia tomentosa (Asan), and various creepers such as Ziziphus species (Kul).

The sanctuary is home to a wide variety of fauna, including both mammals and birds. Prominent mammalian species include the Asian Elephant (Elephas maximus), Asiatic Jackal (Canis aureus), Bandicoot Rat (Bandicota bengalensis), Common Palm Civet (Paradoxurus hermaphroditus), Field Rat (Mus booduga), Grey Mongoose (Herpestes edwardsii), House Mouse (Mus musculus), Indian Grey Wolf (Canis lupus pallipes), Indian Leopard (Panthera pardus fusca), Jungle Cat (Felis chaus), Northern Plains Gray Langur (Semnopithecus entellus), Porcupine (Hystrix indica), Sloth Bear (Melursus ursinus), Spotted Deer (Axis axis), Striped Hyena (Hyaena hyaena), Tree Rat (Rattus rattus arboreus), and Wild Boar (Sus scrofa)35,60,61,62.

Field data collection for Den sites

Field sampling was carried out during the breeding seasons from 2022 to 2024. Information on active and potential den sites was gathered through long-term knowledge shared by local residents and forest department personnel, supported by multiple field visits conducted by the authors. Formal approval for the study was granted by the forest department (Letter No. 749(WL)/2020-21-1153). In our study, “active dens” specifically referred to dens where the presence of pups was confirmed through visual observation or camera trap footage. Dens used as short-term shelters by wolves were not classified as active. Canids are known to hoard bones near their dens32, and the presence of multiple scats around the den typically indicates an active den32,42. Therefore, hoarded bones, wolf tracks, and scat deposits were used as primary indicators to confirm active dens, which was further validated by direct sightings. To confirm the activity status of uncertain den sites, motion-sensor camera traps were installed at each suspected location for a period of 10 nights (Supplementary Information, Figure S2).The camera traps were installed on the closest tree to the den and aimed at the main entrance to capture activity. We ensured minimal disturbance to the dens and collected data without altering the site. Detailed information on den structures, including the number of openings, their position, topographical features, and habitat characteristics, was gathered to better understand the species denning site selection. Site-specific characteristics of the dens were recorded using three concentric circular plots with radii of 15 m, five meter, and one meter, cantered on the den site. Within the 15-meter radius plot, data were collected on individual trees of the dominant species, including measurements of tree height, girth at breast height (GBH), average canopy cover from four points, and average grass height from five points within the plot. In the five meter radius plot, the percentage of shrub cover was documented, while the one meter radius plot was used to estimate the percentage of grass cover. To assess anthropogenic disturbances, evidence of human activity was documented within the 15-meter plot. This included signs such as wood cutting, lopping, human-livestock trails, and the presence of people or livestock. The influence of co-predator abundance on wolf den site selection was evaluated by conducting a 500-meter walk in each of the four cardinal directions from the den site, documenting any indirect signs of co-predators such as leopard (Panthera pardus fusca) and hyena (Hyaena hyaena). Additionally, To analyse the factors influencing den site selection using binomial models, comparable site-specific data were gathered from 40 randomly selected contrast locations within the Mahuadanr forest range of the PTR. The contrast locations were generated using63, and any points overlapping with water bodies, human settlements, or roads were omitted from the analysis.

Variable selection and analysis

We selected five topographical variables for analysis: the number of opening points at each den, the entrance diameter of the openings, slope, elevation, and eight habitat variables, which included tree height, canopy cover, girth at breast height (GBH), shrub cover, shrub height, grass cover, Sal abundance, and the abundance of tree species other than Sal (Table 3). Additionally, we included other variables such as the distance to the nearest waterhole, river, road, and human settlement, along with the relative disturbance index and relative predator presence index. Canopy cover was evaluated at five randomly selected points within the 15-meter plot using ocular estimation, with the den site serving as the central point. The average canopy cover for the plot was then calculated from these measurements. The relative disturbance index was determined by dividing the total count of distinct signs of anthropogenic disturbances—such as woodcutting, lopping, human-livestock trails, and sightings of people or livestock—within the plot by five. Similarly, the relative predator presence index was determined by dividing the total number of signs of leopard and hyena detected across the four directions from the den site by four. The slope was determined using Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM) digital elevation data, which was obtained from the Earth Explorer data archive64. Distances to the nearest waterhole, river, road, and human settlement were calculated using the Euclidean distance tool in ArcGIS65, with Google Earth serving as the reference base map. A Pearson correlation test was performed between the variables prior to developing the candidate models (Supplementary Information, Figure S1). None of the variables exhibited a correlation coefficient greater than 0.7, so all variables were retained for further analysis (Table 3). We then assessed the normality of the dataset’s distribution, and any skewed variables were normalized using a log10 transformation. To examine the factors influencing wolf den site selection, we applied Generalized Linear Models66 to mathematically describe the selection process, ensuring that covariance among explanatory variables was minimized. The selection of error and link functions was informed by the characteristics of the data42. As den presence, a binary response variable (1 = presence, 0 = absence), follows a binomial distribution, a logit link function was applied66. We developed several stepwise models with different variable combinations and evaluated model fit. Models were ranked using Akaike’s Information Criterion (AIC)67 (Tables 1 and 2). All statistical analyses were performed in R statistical software version 4.1.068. Generalized Linear Models (GLMs) were fitted using the MuMIn package69. Additionally, the following R packages were employed during the analysis: ggplot270, MASS71, dplyr72, and pheatmap73.

Data availability

The datasets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Bodasing, T. The decline of large carnivores in Africa and opportunities for change. Biol. Conserv. 274, 109724. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2022.109724 (2022).

Schipper, J. et al. The status of the world’s land and marine mammals: diversity, threat, and knowledge. Science 322, 225–230. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1165115 (2008).

Ripple, W. J. et al. Status and ecological effects of the world’s largest carnivores. Science 343, 1241484. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1241484 (2014).

Ordiz, A. et al. Effects of human disturbance on terrestrial apex predators. Diversity 13, 68. https://doi.org/10.3390/d13020068 (2021).

Di Marco, M. et al. Drivers of extinction risk in African mammals: the interplay of distribution State, human pressure, conservation response and species biology. Philos. Trans. R Soc. B Biol. Sci. 369, 20130198. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2013.0198 (2014).

Loveridge, A. J., Valeix, M., Elliot, N. B. & Macdonald, D. W. The landscape of anthropogenic mortality: how African lions respond to Spatial variation in risk. J. Appl. Ecol. 54, 815–825. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2664.12794 (2017).

Treves, A. & Karanth, K. U. Human-carnivore conflict and perspectives on carnivore management worldwide. Conserv. Biol. 17, 1491–1499. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-1739.2003.00059.x (2003).

van de Kerk, M., de Kroon, H., Conde, D. A. & Jongejans, E. Carnivora population dynamics are as slow and as fast as those of other mammals: implications for their conservation. PLoS One. 8, e70354. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0070354 (2013).

Jhala, Y. et al. Recovery of Tigers in India: critical introspection and potential lessons. People Nat. 3, 281–293. https://doi.org/10.1002/pan3.10177 (2021).

Jhala, Y., Saini, S., Kumar, S. & Qureshi, Q. Distribution, status, and conservation of the Indian Peninsular Wolf. Front. Ecol. Evol. 10, 814966. https://doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2022.814966 (2022).

Mahajan, P., Khandal, D. & Chandrawal, K. Factors influencing habitat use of Indian grey Wolf in the semiarid landscape of Western India. Mamm. Study. 47, 23–37. https://doi.org/10.3106/ms2021-0029 (2021).

Pooley, S., Bhatia, S. & Vasava, A. Rethinking the study of human–wildlife coexistence. Conserv. Biol. 35, 784–793. https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.13653 (2021).

Carter, N. H. & Linnell, J. D. Building a resilient coexistence with wildlife in a more crowded world. PNAS Nexus. 2, pgad030. https://doi.org/10.1093/pnasnexus/pgad030 (2023).

Gao, Y. & Clark, S. G. An interdisciplinary conception of human-wildlife coexistence. J. Nat. Conserv. 73, 126370. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnc.2023.126370 (2023).

Dickman, A. J. Complexities of conflict: the importance of considering social factors for effectively resolving human-wildlife conflict. Anim. Conserv. 13, 458–466. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-1795.2010.00368.x (2010).

Bhatia, S., Redpath, S. M., Suryawanshi, K. & Mishra, C. Beyond conflict: exploring the spectrum of human–wildlife interactions and their underlying mechanisms. Oryx 54, 621–628. https://doi.org/10.1017/S003060531800159X (2020).

Anthwal, A., Gupta, N., Sharma, A., Anthwal, S. & Kim, K. H. Conserving biodiversity through traditional beliefs in sacred groves in Uttarakhand Himalaya, India. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 54, 962–971. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2010.02.003 (2010).

Malhotra, K. C., Gokhale, Y., Chatterjee, S. & Srivastava, S. Cultural and Ecological Dimensions of Sacred Groves in India. 1–30 (INSA, 2011).

Singhal, V., Ghosh, J. & Bhat, S. S. Role of religious beliefs of tribal communities from Jharkhand (India) in biodiversity conservation. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 64, 2277–2299. https://doi.org/10.1080/09640568.2020.1861587 (2021).

Sarma, R. & Mukherjee, R. Spiritual kinship: an insight study of Santhal’s totem world. Think. India J. 22, 4705–4471 (2019).

Census of India. Primary Census Abstract. Registrar General of India, Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India, New Delhi. (2011). https://censusindia.gov.in/census.website/data/data-visualizations/PopulationSearch_PCA_Indicators (accessed 16 April 2024).

Pal, T. Sacred grove in Jharkhand. Indian Int. J. Humanit. Arts Soc. Sci. Res. 1, 60–73 (2016).

Chapman, R. C. The Effects of Human Disturbance on Wolves (Canis Lupus l) (University of Alaska, 1977).

Kumar, S. Ecology and Behaviour of Indian Wolf (Canis lupus pallipes) in the Deccan Grasslands of Solapur, Maharashtra, India. PhD Thesis, Centre for Wildlife and Ornithology, Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh (1998).

Paquet, P. C. & Darimont, C. Yeo Island wolf home site recommendation: A proposed solution to the potential conflict between home site requirements of wolves and areas targeted for timber harvest. In Technical Report Prepared for Raincoast Conservation Society (2002). http://www.raincoast.org.

Joly, K., Craig, T., Cameron, M. D., Gall, A. E. & Sorum, M. S. Lying in wait: limiting factors on a low-density ungulate population and the latent traits that can facilitate escape from them. Acta Oecol. 85, 174–183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actao.2017.11.004 (2017).

McLoughlin, P. D., Walton, L. R., Cluff, H. D., Paquet, P. C. & Ramsay, M. A. Hierarchical habitat selection by tundra wolves. J. Mammal. 85, 576–580. https://doi.org/10.1644/BJK-119 (2004).

Laurenson, M. K. High juvenile mortality in cheetahs (Acinonyx jubatus) and its consequences for maternal care. J. Zool. Lond. 234, 387–408. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7998.1994.tb04855.x (1994).

Benson, J. F., Lotz, M. A. & Jansen, D. Natal Den selection by Florida Panthers. J. Wildl. Manag. 72, 405–410. https://doi.org/10.2193/2007-264 (2008).

Van Ballenberghe, V. & Mech, L. D. Weights, growth, and survival of timber Wolf pups in Minnesota. J. Mammal. 56, 44–63. https://doi.org/10.2307/1379605 (1975).

Jacobs, C. E. & Ausband, D. E. Pup-rearing habitat use in a harvested carnivore. J. Wildl. Manag. 82, 802–809. https://doi.org/10.1002/jwmg.21434 (2018).

Ashish, K., Ramesh, T. & Kalle, R. Striped hyaena Den site selection in Nilgiri biosphere reserve, India. J. Trop. Ecol. 38, 472–479. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0266467422000396 (2022).

Langman, V. A. et al. Moving cheaply: energetics of walking in the African elephant. J. Exp. Biol. 198, 629–632. https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.198.3.629 (1995).

Shahi, S. P. Report of grey Wolf (Canis lupus Pallipes Sykes) in India—a preliminary survey. J. Bombay Nat. Hist. Soc. 79, 493–502 (1982).

Iqbal, S. & Ilyas, O. Patterns of livestock depredation by carnivores: Leopard Panthera Pardus (Linnaeus, 1758) and grey Wolf canis lupus (Linnaeus, 1758) in and around Mahuadanr Wolf sanctuary, Jharkhand, India. J. Threat Taxa. 15, 24291–24298. https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5929-5339 (2023).

Ross, S., Kamnitzer, R., Munkhtsog, B. & Harris, S. Den-site selection is critical for Pallas’s cats (Otocolobus manul). Can. J. Zool. 88, 905–913. https://doi.org/10.1139/Z10-056 (2010).

Fuller, T. K., Mech, L. D. & Cochrane, J. F. Wolf population dynamics. In Wolves: Behavior, Ecology, and Conservation (eds Mech, L. D. & Boitani, L.). Vol. 30. (University of Chicago Press, 2--3). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmr.2013.02.009.

Harrington, F. H. & Mech, L. D. Patterns of homesite attendance in two Minnesota Wolf packs. In Wolves of the World: Perspectives of Behavior, Ecology, and Conservation (eds Harrington, F. H. & Paquet, P. C.). 81–105. (Noyes, 1982).

Eberhardt, L. E., Hanson, W. C., Bengtson, J. L., Garrott, R. A. & Hanson, E. E. Arctic Fox home range characteristics in an oil-development area. J. Wildl. Manag. 46, 183–190. https://doi.org/10.2307/3808421 (1982).

Doncaster, C. P. & Woodroffe, R. Den site can determine shape and size of Badger territories: implications for group-living. Oikos 66, 88–93. https://doi.org/10.2307/3545199 (1993).

Habib, B. & Kumar, S. Den shifting by wolves in semi-wild landscapes in the Deccan plateau, Maharashtra, India. J. Zool. 272, 259–265. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7998.2006.00265.x (2007).

Khan, S., Sadhukhan, S. & Habib, B. There is no place like home: Den and rendezvous site selection of Indian wolves in the human-dominated landscape of Maharashtra. J. Wildl. Sci. 1, 31–39. https://doi.org/10.63033/JWLS.GHWH3024 (2024).

Schwartz, C., Miller, S. & Franzmann, A. Denning ecology of three black bear populations in Alaska. Bears: their Biol. Manag. 7, 281–291 (1987). https://www.jstor.org/stable/3872635

Rabinowitz, A. R. & Pelton, M. R. Day-bed use by raccoons. J. Mammal. 67, 766–769. https://doi.org/10.2307/1381145 (1986).

Iliopoulos, Y., Youlatos, D. & Sgardelis, S. Wolf pack rendezvous site selection in Greece is mainly affected by anthropogenic landscape features. Eur. J. Wildl. Res. 60, 23–34. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10344-013-0746-3 (2014).

Ciucci, P., Boitani, L., Francisci, F. & Andreoli, G. Home range, activity and movements of a Wolf pack in central Italy. J. Zool. 243, 803–819. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7998.1997.tb01977.x (1997).

Theuerkauf, J., Jedrzejewski, W., Schmidt, K. & Gula, R. Segregation of wolves from humans in the Białowieża forest. J. Wildl. Manag. 67, 706–716 (2003). https://www.jstor.org/stable/3802677

Thiel, R. P., Merrill, S. & Mech, L. D. Tolerance by Denning wolves (Canis lupus) to human disturbance. Can. Field-Nat. 122, 340–342 (1998).

Voigt, D. R. Summer Food Habits and Movements of Wolves (Canis Lupus L.) in Central Ontario (University of Guelph, 1973).

Ballard, W. B. & Dau, J. R. Characteristics of Gray Wolf (Canis lupus) Den and rendezvous sites in south-central Alaska. Can. Field-Nat. 97, 299–302 (1983).

Trapp, J. R., Beier, P., Mack, C., Parsons, D. R. & Paquet, P. C. Wolf (Canis lupus) Den site selection in the Rocky mountains. Can. Field-Nat. 122, 49–56. https://doi.org/10.22621/cfn.v122i1.543 (2008).

Ausband, D. E. et al. Surveying predicted rendezvous sites to monitor Gray Wolf populations. J. Wildl. Manag. 74, 1043–1049. https://doi.org/10.2193/2009-303 (2010).

Ahmadi, M., Kaboli, M., Nourani, E., Shabani, A. A. & Ashrafi, S. A predictive Spatial model for Gray Wolf (Canis lupus) Denning sites in a human-dominated landscape in Western Iran. Ecol. Res. 28, 513–521. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11284-013-1040-2 (2013).

Peterson, R. O. & Ciucci, P. The Wolf as a carnivore. In Wolves: Behavior, Ecology, and Conservation (eds Mech, L. D. & Boitani, L.). 104–130. (University of Chicago Press, 2003).

Unger, D. E. Timber Wolf Den and Rendezvous Site Selection in Northwestern Wisconsin and east-central Minnesota (University of Wisconsin–Stevens Point, 1999).

Smith, J. A. et al. Fear of the human ‘super predator’ reduces feeding time in large carnivores. Proc. R. Soc. B 284, 20170433 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2017.0433

Alam, M. D. Status, ecology and conservation of striped hyena (Hyaena hyaena) in Gir National Park and Sanctuary, Gujarat. PhD Thesis, Aligarh Muslim University (2011).

Nikunj, G., Dave, S. M. & Dharaiya, N. Feeding patterns and Den ecology of striped hyena (Hyaena hyaena) in North Gujarat, India. Tigerpaper 36, 13–17 (2009).

Mandal, D. K. Ecology of striped hyena (Hyaena hyaena) in Sariska Tiger Reserve, Rajasthan. PhD Thesis, Saurashtra University, Rajkot, India (2018).

Mahaling, M. K. & Kumar, M. Management Plan of Mahuadanr Wolf Sanctuary 2016–2017 to 2025–2026. Vol. 302 (Palamau Tiger Reserve, Government of Jharkhand, 2021).

Yadav, S. P. et al. Management Effectiveness Evaluation of Tiger Reserves in India, 2022 (Fifth Cycle), Summary Report (Wildlife Institute of India, Dehradun, and National Tiger Conservation Authority, Government of India, 2023).

Rawat, A. S. Tiger Conservation Plan. Palamau Tiger Reserve, Department of Forest, Environment and Climate Change. Vol. 423 (Government of Jharkhand, 2013).

QGIS Development Team. QGIS Geographic Information System. Open Source Geospatial Foundation Project, Austin, Texas (2018). https://www.qgis.org/en/site/

Farr, T. G. et al. The shuttle radar topography mission. Rev. Geophys. 45, 1–33 (2007).

ESRI. ArcGIS Desktop: Release 10 (Environmental Systems Research Institute, 2014).

McCullagh, P. & Nelder, J. A. Binary data. In Generalized Linear Models (eds Cox, D. R. et al.). 2nd edn. 89–148 (Chapman and Hall, 1989).

Burnham, K. P. & Anderson, D. R. Model Selection and Multi-Model Inference: A Practical Information-Theoretic Approach. 2nd edn (Springer, 2002).

R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2020). https://www.R-project.org/

Barton, K. & MuMIn Multi-Model Inference (Springer, 2023).

Wickham, H. Ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis. 2nd edn (Springer, 2023).

Venables, W. N. & Ripley, B. D. Modern Applied Statistics with S.. 4th edn. ISBN 0-387-95457-0 (Springer, 2002). https://www.stats.ox.ac.uk/pub/MASS4/

Wickham, H., François, R., Henry, L., Müller, K. & Vaughan, D. dplyr: A grammar of data manipulation. R package version 1.1.4. (2023). https://github.com/tidyverse/dplyr. https://dplyr.tidyverse.org.

Kolde, R. Pretty Heatmaps. R package version 1.0.12 (2018). https://github.com/raivokolde/pheatmap

Matteson, M. Y. Denning Ecology of Wolves in Northwest Montana and Southern Canadian Rockies (University of Montana, 1992).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the forest staffs of Palamau Tiger Reserve.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SI, OI and UK contributed to the study conception and design. The data collection is done by SI and RD and analysis were carried out by SI, UK, OI, RD, and QQ. The first draft of the manuscript was written by SI. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics declaration

Ethical review and approval were not required for this animal study, as the manuscript does not involve the capture or handling of any animals. All field data collection was conducted in full compliance with the relevant guidelines and regulations outlined by the Principal Chief Conservator of Forests (Wildlife) and the Chief Wildlife Warden of the Jharkhand Forest Department, Government of Jharkhand (Letter No. 749(WL)/2020-21-1153).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Iqbal, S., Desai, R., Kumar, U. et al. Den site selection by Indian gray wolves in tribal landscapes of Mahuadanr Wolf Sanctuary considering ecological and cultural factors. Sci Rep 15, 10060 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-94417-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-94417-z

This article is cited by

-

Investigating the role of ecological and anthropogenic factors in shaping the site use patterns of Gaur (Bos gaurus) in Palamau tiger Reserve, Jharkhand, India

European Journal of Wildlife Research (2025)