Abstract

Thoracic aortic dilatations (TADs) are commonly detected incidentally. A TAD may develop into aortic aneurysm and subsequently lead to aortic dissection, a highly lethal condition. Earlier detection of TADs could improve the surveillance and surgical management of aneurysms, potentially reducing aortic ruptures. The opportunistic use of thoracic sectional imaging studies performed for other indications, including breast radiation therapy planning, could be used to detect TADs. However, the frequency of TADs and the clinical risk factors for TADs in females undergoing adjuvant breast radiation therapy remain unknown. We retrospectively collected a consecutive cohort of 861 females with breast cancer who underwent adjuvant radiotherapy planning with computed tomography (CT). Using CT scans, we manually measured thoracic aortic dimensions on the hospital’s dedicated picture archiving and communication software (PACS). Following the European Society of Cardiology guidelines, a segment of the aorta was considered dilated when its maximal diameter exceeded 40 mm. Additionally, we collected clinical patient data regarding known risk factors predisposing patients to TADs. Out of 861 patients, 80 (9.3%) had a TAD. Compared to those without any TADs, patients with at least one TAD were older (71.3 ± 9.7 years vs. 62.9 ± 11.7 years; P < .001) and more frequently displayed hypertension (62 [77.5%] vs. 354 [45.3%], P < .001), a history of a TIA or stroke (10 [12.5%] vs. 36 [4.6%], P = .007), and aortic valve insufficiency (10 [12.5%] vs. 51 [6.5%], P = .047). The opportunistic use of radiotherapy planning CT scans allows earlier TAD diagnosis, and a significantly large number of female patients (9.3%) had at least one abnormal thoracic aortic dimension. This finding could indicate a need to consider a systematic screening of TADs in patients undergoing adjuvant radiotherapy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Frequently, thoracic aortic dilatations (TADs) and thoracic aortic aneurysms (TAAs) are asymptomatic and thus often detected incidentally1,2. TADs are associated with aortic aneurysms and aortic events, including aortic dissection3,4 and aortic rupture, a rare condition that has mortality rates of 97–100% within 24 h of the event5. The opportunistic use of thoracic sectional imaging studies performed for other reasons could be readily used to detect TADs. Most patients with breast cancer (i.e., patients with local and locally advanced invasive cancer and many patients with ductal carcinoma in situ treated with breast-conserving surgery and high-risk patients treated with mastectomy) are offered postoperative adjuvant radiation therapy (RT;6,7). The latter necessitates thoracic computed tomography (CT) scanning for RT planning, facilitating TAD screening.

The current diagnostic criteria and indications for TAD surgery are based on the dimensions of the thoracic aorta3,4. The European and American criteria for aortic dilatations differ slightly on the definition of aortic dilatations3,4. The European Society of Cardiology (ESC) deems the thoracic aortic dilated if the maximum diameter is > 40 mm3. According to the American College of Cardiology, the maximum diameter of thoracic aortic dilatation varies between males and females according to the level of the aorta (Table 1)4. However, these diameter-based cutoffs are not accurate in risk stratification in patients with short stature or in taller patients3. Indeed, the cutoffs for indexes calculated by dividing the aortic diameter by height (aortic height index [AHI]) and body surface area (aortic size index [ASI]) have been shown to predict complications associated with aortic abnormalities more accurately than the diameter-based cutoffs4. Of these measures, AHI is more reliable because ASI is partially dependent on the patient’s weight, which can fluctuate during the follow-up time8. The European and American criteria for aortic dilatation, surgical operation, and the follow-up recommendations are summarized in Table 1.

The prevalence of incidentally detected TAD in populations scanned for non-cardiovascular reasons utilizing varying criteria has ranged from 2.7 to 8%9,10,11. Given the apparent potential of RT planning CT scans for opportunistic TAD screening, the aim of this study was to evaluate the prevalence of TADs among females imaged for adjuvant breast RT. We hypothesized that a high prevalence of TAD in this population could indicate a need for systematic evaluation of the aortic diameters in RT planning CT scans.

Materials and methods

Patients

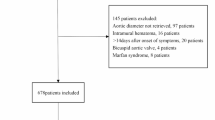

We retrospectively collected data from consecutive female patients with newly diagnosed non-invasive and invasive breast cancer who underwent an RT planning CT scan in Tampere University Hospital during 2019–2020. Patients undergoing palliative RT were excluded because this population affected by an incurable disease would likely not benefit from systematic screening for aortic dilatation.

The study was approved, and the need for patients’ consent was waived by the institutional review board of Tampere University Hospital (study identifier: R22628) according to national law and local regulations. All research was performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Computed tomography protocol

Patients with breast cancer scheduled for postoperative radiotherapy underwent a planning CT scan of the chest to allow the delineation of RT targets (the breast/chest wall and, when indicated, the area requiring a booster dose and the lymph node regions; 8).

In this study, CT imaging was performed during the study period according to routine clinical practice using one of the three CT scanners (Philips Brilliance Big Bore [Philips Healthcare, the Netherlands], Siemens SOMATOM Confidence 64 [Siemens Healthineers, Germany] or Toshiba Aquilion LB [Toshiba Medical System, Japan]) without contrast agent or electrocardiogram gating. The patients were scanned in the supine position with both hands above the head. Sabella Flex Positioning System (CDR Systems, Canada) was used with a 10° tilt for patient immobilization. Additionally, patients with left-sided breast cancer were imaged with deep inspiration breath hold to minimize radiation dose to the heart during the RT. The tube voltage was set to 120 kVp, and the tube current and the CT scanner exposure time per rotation were automatically adjusted according to the patient’s size, varying between 100 and 350 mAs. Finally, the slice thickness was 3 mm, and the scanning area extended cranially above the jawline and caudally below the diaphragm, covering the breasts and lungs.

Radiological measurements

One reader (A.L.) measured the thoracic aortic diameters on the hospital’s Picture Archiving and Communication Systems (PACS; Sectra vs. 24.2.). Multiplanar reconstruction (MPR) of the image stacks were used to allow three-dimensional presentation of the structures. The thoracic aortic diameters were measured from the following segments: the sinus of Valsalva, sinotubular junction, tubular part, mid-aortic arch, and mid-descending (thoracic) aorta (DA; Fig. 1)4. The reader measured two perpendicular measurements from these segments, the other representing the maximum diameter. Measurements were obtained by drawing lines from the outer-to-outer vascular wall, vertical to the centerline of the vessel3. Next, the maximum diameter of the aorta was used for statistical analyses. The thoracic aorta was considered dilated if its greatest dimension was > 40 mm in any of the measured planes3. Lastly, AHI and ASI determination and results are presented and discussed in the Supplementary Materials.

A schematic presentation of the thoracic measurement segments (left) and a sagittal view image (right). A: sinus of Valsalva, B: sinotubular junction, C: tubular part, D: mid-aortic arch, E: mid-descending (thoracic) aorta, P: right pulmonary artery. The dashed line indicates the level of the diaphragm.

To evaluate intra- and inter-reader reproducibility, the reader (A.L.) reanalyzed a randomly selected subset of 50 patients, and another reader (M.L.) measured the same 50 patients twice. The interval between the first and second measurements was to be a minimum of five days.

Clinical variables

After performing the measurements, one reader (A.L.) reviewed patients’ medical history, including medications, from patient records. The reader collected a comprehensive clinical patient dataset, encompassing established risk factors associated with TADs. These factors included the diagnosis of hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, diabetes, arteritis, vasculitis, or coronary artery disease; a detailed smoking history; a history of transient ischemic attack (TIA)/stroke; aortic valve regurgitation; and stenosis. Additionally, we compiled information pertaining to body mass index (BMI).

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS (version 26, 1989–2019 SPSS Inc, USA). Statistical significance was set to a P value ≤ 0.05. Unless otherwise stated, continuous variables are presented as means ± standard deviations (SDs) and interquartile ranges (IQRs) and categorical numbers as crude numbers and percentage shares.

We used the intra-class correlation coefficient test to evaluate the intra- and inter-reader reproducibility. We employed the two-way mixed model to evaluate the absolute agreement and report the average measurements. Additionally, we used the Chi-square test to test the statistical difference between categorical values, and when the assumptions were violated, we employed the Fischer’s exact test. We used the Mann–Whitney U test to study the differences in continuous variables between groups.

Results

Patient characteristics

We retrospectively enrolled 861 (mean age 63.7 ± 11.7 years; IQR: 54.9, 73.2 years) female patients with breast cancer who underwent thoracic CT scan for adjuvant RT planning. Patient characteristics and the mean aortic dimensions are presented in Tables 2 and 3, respectively.

Intra- and inter-reader reproducibility

The intra-reader reproducibility of the measurements of 50 patients was excellent for thoracic aortic measurements (0.832–0.999 / 0.797–0.976 [P < 0.001 for all]) and HAA (0.830 / 0.905 [P < 0.001 for both]) measurements for readers 1 and 2, respectively (Table 4, Supplementary Materials). The inter-reader reproducibility of the measurements of the same patients was excellent for thoracic aortic (first measurements: 0.831–0.959, repeated measurements: 0.725–0.967 [P < 0.001 for all]) and HAA (first measurements: 0.733, repeated measurements: 0.845 [P < 0.001 for both]) measurements (Table 4, Supplementary Materials).

TAD prevalence

Out of 861 patients, 80 (9.3%) had at least one TAD defined as a maximal aortic diameter of > mm in any of the thoracic aortic segments. Out of 80 patients with at least one dilated aortic measurement, 32 (40.0%) patients had a dilated sinus of Valsalva, and 53 (66.3%) had a dilated tubular diameter. Fewer than five females had a dilatation of the sinotubular junction, aortic arch, or DA. Notably, these measurements are not mutually exclusive.

Differences in risk factors between patients with and without TAD

Compared to patients without any TADs, those with at least one TAD (thoracic aortic diameter > 40 mm) were older (71.3 ± 9.7 years vs. 62.9 ± 11.7 years; P < 0.001), more often displayed hypertension (62 [77.5%] vs. 354 [45.3%], P < 0.001), a history of a TIA or stroke (10 [12.5%] vs. 36 [4.6%], P = 0.007), and aortic valve regurgitation (10 [12.5%] vs. 51 [6.5%], P = 0.047). Furthermore, patients with at least one TAD had a smaller mean HAA (124.0° ± 8.0° vs. 128.3° ± 8.0°, P < 0.001) than those without any TADs.

Discussion

Although thoracic aortic dilatations are associated with lethal conditions, they are frequently asymptomatic, making their early detection challenging. There has been no previous research regarding the prevalence of TADs in patients with breast cancer. Our study aimed to determine the utility of RT planning CT scans for TAD screening. The prevalence of TADs detected on RT planning CT scans according to the maximum diameter-based criterion (> 40 mm) was 9.3% in our cohort. Patients with at least one TAD were older, more frequently affected by hypertension, and had more frequently had a TIA or stroke and aortic valve regurgitation than patients without any TADs. Given the high prevalence of TADs and because RT planning CT scans are not normally reported by radiologists, we believe that a substantial number of TADs may go unnoticed. Further research is needed to investigate whether a more systematic evaluation of the thoracic aorta could produce fewer aortic events during a follow-up to support screening practice.

The prevalence of TADs varies throughout the literature. For instance, Benedetti et al. reported that the incidentally detected TADs was 2.7% out 24,992 patients with a mean age of 66 years who had undergone routine chest CT for various indications12. Elsewhere, Mori et al. reported the prevalence of incidentally identified ascending aortic dilatation to be 1.1% in patients aged 50–64 years and 4.0% in patients aged 65–84 years in a population of 5,662 patients scanned for any indication in a single tertiary Canadian institution10. Ramchand et al., using CT scans of 1000 adult male and female cardiac patients with atrial fibrillation evaluated for pulmonary vein isolation (a catheter ablation technique), showed that 20% of the patients in this population had dilated aorta, and 1% had significant aortic enlargement (> 5.0 cm;13). The prevalence of aortic dilatation of 9.3% in our cohort fell between these prevalence rates, likely reflecting the number and severity of cardiac comorbidities in the studies. Notably, all patients in our cohort were females, unlike in previous studies, where the incidence of TADs has been lower in females14.

TADs can lead to aortic aneurysms, predisposing the patient to a fatal thoracic aortic rupture. Detecting aortic dilatation at an early stage and regularly monitoring this condition could prevent aortic ruptures and unnecessary mortality. However, aortic dilatation is often asymptomatic and typically screened only if the patient has genetic risk factors3. Indeed, most dilatations of the thoracic aorta are detected as incidental findings in patients undergoing thoracic imaging for unrelated reasons3. Thus, the opportunistic use of RT planning CT scans for early detection of aortic dilatations could be a valuable approach to identifying patients with asymptomatic TADs. Indeed, breast cancer is the most common cancer among females15, and most patients diagnosed with breast cancer are treated with postoperative RT. In Finland, the incidence of breast cancer was 170.6 per 100,000 females in 202216. Leveraging RT planning CT scans for the opportunistic screening of aortic dilatation could help identify 15.9 female patients with undiagnosed aortic dilatation per 100,000 females who should be monitored for TAD growth. Moreover, the prognosis of treated female breast cancer has considerably improved17. Therefore, the relevance of TAD detection in this population is growingly important.

This study had certain limitations. We were able to collect a relatively large consecutive retrospective dataset of patients diagnosed with breast cancer who had undergone adjuvant breast RT. Nevertheless, the main limitation of the study was that these patients underwent non-contrast aortic imaging, solely allowing the measurement of the outer-to-outer vascular wall (i.e., the lumen could not be distinguished). The difference in contrast versus non-contrast CT-based aortic dimensions has varied from 2 to 6 mm18. Since the guidelines were based on contrast imaging, this study might have slightly overestimated the prevalence of aortic dilatation. Furthermore, although we were able to consider multiple risk factors for TAD, a prospectively collected dataset could be amended using other factors, such as family risk. Additionally, we did not have long-term follow-up data, and therefore, long-term outcomes and cost–benefit analyses for integrating the opportunistic screening of TADs and their inevitable follow-up costs are needed before recommending systematic evaluation for screening of the aortic diameters.

Overall, the prevalence of aortic dilatation was 9.3% in female patients undergoing chest CT for RT planning. Patients diagnosed with breast cancer with at least one TAD had more known risk factors for TADs than patients without TADs. The opportunistic use of RT planning CT scans could facilitate earlier detection of TADs. Ultimately, there is a need for further research on the systematic screening of TADs in females treated for breast cancer and undergoing RT planning CTs.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files. Individual-level data is not shareable.

References

Saeyeldin, A. A. et al. Thoracic aortic aneurysm: Unlocking the “silent killer” secrets. Gen. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 67, 1–11 (2019).

Singh, P., Almarzooq, Z., Salata, B. & Devereux, R. B. Role of molecular imaging with positron emission tomographic in aortic aneurysms. J. Thorac. Dis. 9, 333–342 (2017).

Erbel, R. et al. ESC Guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of aortic diseases: Document covering acute and chronic aortic diseases of the thoracic and abdominal aorta of the adult The Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Aortic Diseases of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 35, 2873–2926 (2014).

Hiratzka, L. F. et al. ACCF/AHA/AATS/ACR/ASA/SCA/SCAI/SIR/STS/SVM guidelines for the diagnosis and management of patients with Thoracic Aortic Disease: A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines, American Association for Thoracic Surgery, American College of Radiology, American Stroke Association, Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society of Interventional Radiology, Society of Thoracic Surgeons, and Society for Vascular Medicine. Circulation. 121, 266–369 (2010).

Johansson, G., Markström, U. & Swedenborg, J. Ruptured thoracic aortic aneurysms: A study of incidence and mortality rates. J. Vasc. Surg. 21, 985–988 (1995).

Cardoso, F. et al. Early breast cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 30, 1194–1220 (2019).

National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Guidelines [Internet]. 2023. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology.

Zafar, M. A. et al. Height alone, rather than body surface area, suffices for risk estimation in ascending aortic aneurysm. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 155, 1938–1950 (2018).

Secchi, F. et al. Detection of incidental cardiac findings in noncardiac chest computed tomography. Medicine. 96, e7531 (2017).

Mori, M. et al. Prevalence of incidentally identified thoracic aortic dilations: Insights for screening criteria. Can. J. Cardiol. 35, 892–898 (2019).

Foley, P. W., Hamaad, A., El-Gendi, H. & Leyva, F. Incidental cardiac findings on computed tomography imaging of the thorax. BMC Res. Notes. 3, 326 (2010).

Benedetti, N. & Hope, M. D. Prevalence and significance of incidentally noted dilation of the ascending aorta on routine chest computed tomography in older patients. J. Comput. Assist. Tomogr. 39, 109–111 (2015).

Ramchand, J. et al. Incidental thoracic aortic dilation on chest computed tomography in patients with atrial fibrillation. Am. J. Cardiol. 140, 78–82 (2021).

Kauhanen, S. P. et al. High prevalence of ascending aortic dilatation in a consecutive coronary CT angiography patient population. Eur. Radiol. 30, 1079–1087 (2020).

Sung, H. et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 71, 209–249 (2021).

European Commission. European Cancer Information System (ECIS) [Internet]. 2022. ECIS - European Cancer Information System.

Taylor, C. et al. Breast cancer mortality in 500 000 women with early invasive breast cancer diagnosed in England, 1993–2015: Population based observational cohort study. BMJ. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj-2022-074684 (2023).

Elefteriades, J. A., Mukherjee, S. K. & Mojibian, H. Discrepancies in measurement of the thoracic aorta: JACC review topic of the week. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 76, 201–217 (2020).

Funding

The study was supported by grants from the Finnish Medical Foundation, Cancer Foundation Finland, and Orion Research Foundation. The funders had no role in the design of this study, its execution, analyses, interpretation of the data, or the decision to publish the results.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Guarantor of integrity for the entire study, O.A.; study concepts/study design or data acquisition or data analysis/interpretation, A.L., P.K., A.M., M.H., I.R.-K., T.S., O.A.; manuscript drafting, A.L.; manuscript revision for important intellectual content, all authors; approval of the final version of the submitted manuscript, all authors; agrees to ensure any questions related to the work are appropriately resolved, all authors; literature research, A.L.; statistical analyses, A.L., O.A.; and manuscript editing, all authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved, and the need for patients’ consent was waived by the institutional review board of Tampere University Hospital (study identifier: R22628) according to national law and local regulations.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lattu, A., Kauhanen, P., Mennander, A. et al. Prevalence and risk factors of thoracic aortic dilatation detected incidentally in adjuvant radiotherapy planning CT scans in patients with breast cancer. Sci Rep 15, 22883 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-94420-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-94420-4