Abstract

The proliferation of holopelagic Sargassum spp. (Sargassum) in the tropical North Atlantic Ocean is of concern for populations and coastal ecosystems in the Caribbean Sea, Gulf of Mexico, and West Africa. Satellite detections have enabled rough assessments of the quantity of algae that drifts seasonally in the open ocean, with seasonal peaks of Sargassum biomass reaching 10 to 20 million tons since 2018. Although the impacts on the coast have been widely publicized, there are no estimates of the quantities of Sargassum that accumulate on the coasts. This study proposes novel vulnerability indicators that combine information on Sargassum stranded biomass, ecosystem and socioeconomic factors to assess risks posed by Sargassum on coastal regions. Quantities of Sargassum that accumulate in the coastal strip at the regional scale were derived by combining the satellite detections in the open ocean with an algal growth-transport-stranding model. It shows that the amount of Sargassum accumulating on the Atlantic coast is of the order of 10% of the biomass estimated offshore and has accumulated between 2 and 10 million tons per year over the last five years. Vulnerability indices identify the Mexican Caribbean, northern Lesser Antilles, and eastern Great Antilles as the most vulnerable regions, facing significant ecosystemic and socioeconomic pressures from Sargassum influxes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The increase in the size of recurring blooms of holopelagic Sargassum species (Sargassum) in the Tropical North Atlantic since 2011 has been a growing concern for coastal populations on both sides of the basin. This macroalga has been present in the North Atlantic subtropical gyre and in the Gulf of Mexico for centuries, but recently it also proliferates in the Tropical North Atlantic1,2,3,4. This has caused unprecedented exposure of human communities and ecosystems to vulnerabilities related to water quality, access to beaches, and mortality of organisms in coastal aquatic ecosystems5.

When Sargassum reaches beaches, it decomposes, and this produces hydrogen sulfide methane and ammonia gasses. These can affect the health of coastal populations. Currently, there is insufficient information on the long-term effects of Sargassum strandings on human populations. In the West French Indies, clinical data collected at the University Hospital of Martinique showed that patients exposed to Sargassum piles complained of non-specific neurological, digestive, respiratory, ocular, and psychological disorders6. Measurements taken in the north-east Yucatan7 suggest that there is no immediate and significant exposure risk for residents or tourists. However, they indicate a higher risk for cleanup workers who are directly exposed to the decomposing Sargassum biomass. Stranded sargassum is also rich in heavy metals, particularly arsenic, which limits its potential for downstream use in food, agriculture, energy production, or biomaterial valorization8. Massive Sargassum accumulation at the coast also puts tropical coastal habitats at risk. They reduce light penetration, increase local water temperature, and can lead to anoxic conditions. Studies have shown that accumulation at the coast causes seagrass die-off on the Mexican coast9,10. Additionally, the leachate from decomposing Sargassum, which contains high levels of arsenic, can disrupt the successful settlement of coral larvae, hindering their ability to reproduce and grow11. Mangroves are also impacted. In 2020, the DEAL in Martinique observed a high mortality rate of mangroves on 26 windward sites which were under influence of the influx of Sargassum12.

Remote sensing detection allows for large-scale monitoring of the Sargassum in the open ocean. Various authors have estimated the Sargassum biomass drifting off the coasts of the Tropical Atlantic from intermediate resolution remote sensing observations2,4,13,14,15,16,17. Although uncertainties remain high, these estimates are crucial for monitoring the phenomenon on a large scale and for feeding monitoring and forecasting systems15,18,19,20. However, the exposure of populations and coastal ecosystems in the Caribbean Sea, Gulf of Mexico, and West Africa depends mainly on the amount of Sargassum biomass that accumulates on the coast or washes up on the shore, rather than the quantities present offshore. The remote sensing observations of biomass across the Tropical North Atlantic are typically derived using sensors at intermediate resolution (250 m to 1,000 m pixel resolution such as provided by MODIS or OLCI sensors; see methodology in Methods section). These observations do not allow monitoring the accumulation of Sargassum along coastlines. Higher-resolution observations, such as those provided by Landsat or Sentinel 2, help observe the Sargassum mats and stranding at the local scale21,22,23, but they are not useful for high-frequency monitoring because they have revisit period ranging from several days to over two weeks. Further, no operational basin-scale composite products are currently available at these high spatial resolutions and high temporal frequency.

Citizen science, local and governmental reporting has also contributed to the observations24. But uncertainties remain large. As an illustration, six different sources - state, federal and local - for the volume of Sargassum collected in 2018 in Quintana Roo (Mexico), reported high variability in the amount and quality of information25. Reported amounts ranged from 5 000 tons to 500 000 tons collected for the same locations and times. Using estimated volumes of Sargassum collected and reported by hotels in Quintana Roo (Mexico) in 2018–2019, the estimation of mean monthly volume of Sargassum stranding is of order 1800 m3 per km of shoreline in the northeast sector of the Yucatan Peninsula26. For other territories, estimates of Sargassum biomass that arrives at the coast are scarce. Any estimates are not standardized, limiting their use for quantitative studies at basin scale and hindering comparison with patterns observed over larger scales.

The aim of this study is to fill this gap. We provide estimates of the amount of Sargassum reaching the coast using satellite images and inferences gained with numerical simulations and Sargassum transport models. We relate these to the economic and socio-economic characteristics of the coastal environment and provide vulnerability indicators. This allows us to put the different regions, populations and ecosystems affected into perspective on a basin-wide scale.

More than 10 million tons of Sargassum stranded per year

This study fills a gap identified in several recent studies27,28, namely, to derive harmonized estimates of the volumes of Sargassum strandings across the Tropical North Atlantic Ocean. To obtain such estimates, we combined open-ocean remote sensing observations and a Sargassum transport-physiology-stranding model at 1/12° resolution. This model has been used to understand and document Sargassum bloom formation and dispersal for the period 2002–20234,15,29. Remote sensing detections are used to nudge the model offshore estimates of Sargassum biomass. Due to large uncertainties in the observations, the modeled Sargassum is not restored to the observations within 50 km of the coast. A stranding parametrization has been developed to quantify the amount of Sargassum that accumulates at the coastline. Details on the model and Sargassum stranding parametrization are given in the Method section.

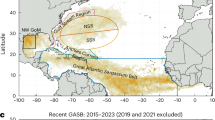

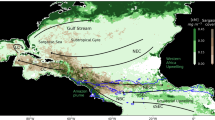

The estimated annual amount of stranded Sargassum for the period 2018–2023 is mapped on 1°x1° (Fig. 1). The values emphasize the impact of the phenomenon on the entire Antilles Island arc and the Yucatan coast. The map shows that some 1°x1° areas (i.e. ~100 km of coastline) may have received over 100,000 tons of Sargassum per year in recent years. The West African coast also receives Sargassum, but in amounts that are on average about 10 times lower than in the Caribbean. Continental areas and islands in the southern Caribbean Sea are generally free of Sargassum arrivals because of the Ekman drift which is oriented North-northwest and upwelling at the coast30,31,32,33,34.

Annual Sargassum cover from MODIS [per mill] and estimation of Sargassum stranding for the period 2018–2023 [in tons per year]. Sargassum cover is shown on a 1/4° and stranding is shown on a grid of 1° resolution. Stranding pixels with less than 1000 tons per year are not considered. Map was created using Geopandas 0.14.2 (https://geopandas.org).

The estimates of Sargassum biomass in this study, whether offshore or stranded, rely heavily on the conversion factor used to translate satellite-derived Sargassum coverage into wet biomass. Here, we adopt the widely used value of 3.34 kg/m² of fresh weight for pure Sargassum patches35. This approach introduces substantial uncertainties in basin-scale biomass estimates. Ref35 measured Sargassum density in the Gulf of Mexico and the Florida Straits, reporting values ranging from 1.26 to 6.74 kg m−2, highlighting the natural variability in Sargassum density in the open ocean. This variability likely results from differences in aggregation processes influenced by ocean currents, wind, and biological factors. Our basin-scale offshore biomass estimates are in line with state of the art estimates2 but as other estimates, they should be interpreted with caution. A comparison between the modeled stranded volumes and available observations in two key regions (Martinique and Quintana Roo, Mexico; see Methods) suggests that the model captures the correct order of magnitude of the stranded volumes. This consistency in two key areas supports the extrapolation of the stranding results to the broader Atlantic basin.

Stranding risk exposure is not uniform in the Tropical North Atlantic. For example, the eastern coast of the Yucatan Peninsula (Mexican Caribbean) has high stranding rates despite relatively persistent low offshore biomass estimates in the region, especially compared to areas east of the Lesser Antilles (Fig. 1). An explanation is that in this region, the orientation of the coast, the transport of Sargassum close to the coast by the Yucatan Current and the onshore winds are particularly favorable to stranding. However, on average and integrated over the Tropical North Atlantic basin, the biomass that reaches the coast every month (Fig. 2b) or every year (Fig. 2c) is closely linked to the open ocean biomass (Fig. 2a). During recent summer months, our estimates indicate that over two million tons of Sargassum arrive on coastlines each month (Fig. 2b). This represents approximately 10% of the total biomass present in the Tropical Atlantic during these months, which can reach up to 20 million tons (Fig. 2a). When cumulative strandings are considered over an entire year, total stranded biomass can reach 10 million tons, as observed in 2018 (Fig. 2c).

(a) Monthly time series of Sargassum biomass estimated from MODIS (blue) and obtained from the NEMO-Sarg 1/12° nudged simulation (red). The biomass is integrated over an area ranging from 100°W to 0°E and from 0°S to 30°N. (b) Monthly stranding rate [Million tons per month] and (c) annual stranding rate [Million tons per year] computed from NEMO-Sarg. Time series were plotted using Matplotlib 3.8.2 (https://matplotlib.org).

A Sargassum socio-ecological vulnerability index

The Coastal Vulnerability Index (CVI) is a useful tool for understanding and anticipating the risks to which coastal zones are exposed. They are commonly used to assess the sensitivity of a coastline to various stress factors, such as sea-level rise, coastal erosion or extreme events36,37,38,39. The inclusion of Sargassum stressor in CVIs has become a necessity in view of the significant increase in mass strandings of this brown alga on the Caribbean and Atlantic coasts. In a first attempt to develop such an index, two elements emerge from discussions with communities in the tropical Atlantic as fundamental40: the impacts on the coastal ecosystem and the socio-economical impacts. Impact on the coastal ecosystem can be assessed based on coastal habitat type, including occurrence of mangroves, coastal coral reefs, and seagrass beds41,42. We estimated the fraction of coastline covered by each habitat in each coastal grid cell of the model (1/12° resolution). Socio-economic impacts can be calculated as a function of the coastal population and the number of tourists per year42,43. We excluded factors such as the impact of Sargassum strandings on fisheries44, and coastal erosion9, which have been poorly documented and therefore are hard to parameterize.

A Coastal Vulnerability Index to Sargassum stranding (SVI for Sargassum Vulnerability Index) is calculated as a linear combination of sub-indexes, following a strategy already employed to infer coastal vulnerability to natural hazards36,39:

The different sub-indexes are computed from ranking variables (defined in Table 1). A vulnerability rank from 1 to 5 is assigned to each of these variables36. This can be a very subjective approach. Therefore, we chose to use a classification based on the Fisher-Jenks algorithm45 a method that seeks to reduce the variance within classes and maximize the variance between classes. The results of this classification for each variable are shown in Table 1. The subindex are then computed as follows:

Forcing subindex = | Rstranding | ,

SocioEconomic subindex = | Rpop + Rtourism | ,

Ecosystem subindex = |Rmangrove + Rseagrass + Rreef|,

with “|” standing for linear rescaling so the term ranges between 0 and 1. This ensures that the different subindexes have the same weight in the SVI computation. Finally, the Jenks algorithm is applied to the SVI to build a SVI classification ranging from 1 to 5.

The SVI provides information on the overall vulnerability, so two other vulnerability indexes SVI_SOCIO and SVI_ECOSYS are derived to estimate and map socio-economic and ecosystem vulnerabilities:

Most vulnerable regions to Sargassum stranding

The SVI identify the Mexican Caribbean coasts, the northern Lesser Antilles, and eastern Great Antilles as the most vulnerable regions to Sargassum influxes (Fig. 3a). These regions face significant ecosystem and socioeconomic pressures (Fig. 3bc).

Map of coastal vulnerability index computed from estimated stranding from 2018 to 2023: (a) total coastal vulnerability (SVI), (b) ecosystemic coastal vulnerability (SVI_ECOSYS) and (c) socioeconomic coastal vulnerability (SVI_SOCIO). Maps were created using Geopandas 0.14.2 (https://geopandas.org).

The maps reveal the high vulnerability of eastern coast of the Yucatan peninsula in Mexican Caribbean. On a closer examination, this coast is unevenly affected and there tend to be more significant groundings between 20°N and Cozumel Island (Fig. 4e–h). The distribution of the stranding generated by our model is consistent with studies that suggest that the Mexican Caribbean is highly prone to Sargassum landings, with maximum landings along this coastal stretch near Cozumel island26,46. The socio economic vulnerability is weak to moderate south of 20°S, as it is sparsely populated and developed, but the ecosystems are particularly vulnerable to strandings (Fig. 4f–h). The northern Lesser Antilles and eastern Greater Antilles are also highly exposed to Sargassum stranding. The index highlights that all these islands are affected. The windward coasts show much higher vulnerability to receiving Sargassum than the leeward coasts (Fig. 4a–d). Africa experiences moderate to high levels of vulnerability, particularly on the coasts of Guinea and Ghana (Fig. 3a). Guinea is mainly exposed to ecosystem vulnerability, but Ghana has high combined vulnerabilities (Fig. 4i–l).

Annual stranding estimated on 1/12° (~ 9 km x 9 km) grid cells for the period 2018–2023, in tons per year for (a–d) the Lesser Antilles, (e–h) the western Caribbean Sea and (i–l) on the coast of Ghana. Maps were created using Geopandas 0.14.2 (https://geopandas.org).

A diagnosis by country is shown in Fig. 5. Estimates suggest that the Dominican Republic, Mexican Caribbean, the Bahamas, Cuba (southeastern coast), Haiti and Puerto Rico have the highest exposure, with an estimation of more than 300 Ktons washing up on their sargassum-exposed shores each year. Figure 5 also reveal that the northern islands of the Lesser Antilles (St. Lucia, Dominica, Martinique, Barbados, St. Vincent and the Grenadines) are those experiencing the greatest vulnerabilities, with more than half of their coastline exposed to high or very high levels of Sargassum landings.

Estimations of Sargassum annual stranding by country (average over the period 2018–2023) as total biomass per country (left) and as coastal pressure in tons/km of coast (right). The figure was created using Matplotlib 3.8.2 (https://matplotlib.org).

Limitations and way forward

This study provides a first look at socio-economic and ecosystem vulnerability in the Tropical North Atlantic. It does not consider very fine-scale dynamics of circulation and transport of Sargassum near the coast47, nor the complexity of the phenomena of deposition and removal of Sargassum from the coast48 due to interactions between waves, currents, tides, wind and coastal geomorphology, for example. There is generally a lack of background information and understanding about coastal dynamics in determining coastal stranding or accumulation at the scale of bays, estuaries, lagoons, open beaches or areas such as ports and boat harbors. Improving such knowledge would require monitoring of Sargassum transport at the scale of the shelf, combined with observations and modelling of the coastal hydrodynamics.

Access to databases on stranded Sargassum volumes and Sargassum density in the open ocean is crucial for refining basin-scale biomass estimates. Long-term monitoring efforts in Puerto Morelos (Mexico) have revealed significant discrepancies between studies, with difference in estimations of stranded volume of one order of magnitude26,49. These differences highlight the challenges of implementing consistent monitoring programs, even in localized areas. Yet, such ground-truth data is essential for calibrating large-scale modeling tools like the one proposed in this study. Strengthening data collection efforts in this field is therefore critical to improving biomass estimates and advancing our understanding of Sargassum dynamics.

Despite the uncertainties, we expect that the stranding assessment derived from the models provides a way to focus possible mitigation or recovery efforts and helps raise the level of awareness of the countries concerned50.

Methods

Remote sensing estimates of Sargassum biomass

The detection of pelagic Sargassum is based on the Alternative Floating Algae Index (AFAI;14) and multispectral observations from the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS). Remote sensing relies on the distinct spectral reflectance properties of Sargassum, particularly its strong near-infrared (NIR) reflectance51. Basin-scale mapping using medium-resolution satellite data began in 2011, coinciding with the onset of massive Sargassum proliferations1,13. Since then, detection methods have been refined through improvements in spectral indices and filtering techniques14, remaining a valuable tool for monitoring, understanding and forecasting Sargassum distribution2,4,15,16,17,51,52. For this study, daily 1 km resolution composites of Sargassum detections were derived from MODIS-Terra and MODIS-Aqua acquisitions53. These 1 km composites were then downscaled onto a regular 1/12° (~ 9 km) grid, enabling near-real-time, basin-wide monitoring of Sargassum in the Atlantic Ocean since MODIS launched in 2002. Sargassum areal coverage was converted into wet weight biomass using an assumed floating density of 3.34 kg m−235.

The Sargassum model

The Sargassum transport model used is NEMO-Sarg29. This Sargassum transport, physiology and stranding model has demonstrated its ability to reproduce the seasonal distribution of Sargassum4,15,29, suggesting that transport and growth/mortality characteristics are realistically represented. For this study, the domain extends between 15°S-50°N and 100°W-25°E and the resolution is 1/12° to capture some of the complexity of the geography.

Sargassum advection is a function of surface currents, Stokes drift and a windage contribution estimated at 0.1% of the wind at 10 m. Such windage value is far lower than the standards given in the literature, which are generally of order 1–3%17,54,55 but in line with values inferred from laboratory experiments56.

The resolution of 1/12° does not resolve the full complexity of coastal dynamics but it has been chosen for consistency with the resolution of the ocean reanalysis GLORYS12 (1/12°)57 which provides the currents, temperature, and salinity to force the NEMO-Sarg model. Winds and irradiance are obtained from the atmospheric reanalysis ERA5, and the biogeochemical field (NO3, PO4, Fe, NH4) that support growth are obtained from a global NEMO-PISCES simulation at ¼° resolution58. The Sargassum model is integrated from 2002 to 2023.

Although the model performs well on a seasonal scale4,15,29, it has biases in long integrations and misses part of the interannual variability, and a nudging toward the observed Sargassum coverage was applied so the model matches the observations as closely as possible. The nudging is only applied on cloud-free pixels, with a restoring time scale of 7 days. An important point is that we do not apply the restoring in a strip from the coast to 50 km offshore so the Sargassum can be freely advected on the shelf and is not affected by the restoring and possible false detections close to the coast.

The Sargassum coverage represented by the nudged model is shown in Fig. S1 for two seasons and averaged from 2018 to 2023. This strategy allows for a correct representation of the amount of Sargassum present in the north Tropical Atlantic.

Stranding parametrization

Stranding occurs at coastal points in the model and is activated when Sargassum transport is directed towards the coast. It is important to note that we do not differentiate between the part washed up on the beach and that accumulated along the coast, and that we refer to these two components as stranded. If Sargassum drift is directed shoreward for an entire day, 100% of the biomass in the coastal pixel strands in one day. This is a very crude parametrization to account for the possibility of fine scale dynamics to transport Sargassum alongshore or to allow offshore export of Sargassum in case of offshore winds.

Validation of stranded quantities

Although citizen science initiatives provide valuable information on the regional distribution and temporal patterns of strandings, they do not allow for precise estimations of stranded or accumulated quantities. The data aggregated regionally from some local reports may also lead to biased regional estimates due to varying levels of engagement from users in reporting strandings at different times and locations; there is no sustained operational regional reporting approach or even guidelines that are accepted everywhere. Consequently, validating our estimates of stranded quantities can only be done using spotty reports from instances where surveys have been conducted using methodologies that attempt to be standardized but are only used occasionally and in limited locations. We identified two key regions with contrasting oceanographic dynamics (Martinique in the French Indies and Puerto Morelos in Mexico) that allowed us to assess the validity of our results. At this stage, we do not differentiate between stranded and nearshore-accumulated quantities. Both have negative environmental impacts that we don’t have the scope to evaluate in this study; thus, we consider total accumulated quantities for first-order validation.

To ensure consistency across different studies, which may measure dry or wet volumes and sometimes surface coverage in m2, we had to establish conversion parameters. The dry-to-wet ratio was set to 15% based on measurements at Puerto Morelos49 with reported values range from 14.2 to 18.4%). We adopt a mean wet mass-to-volume ratio of 270 kg m−3, a value within the observed range reported of 200–420 kg m−359. In the open ocean, we assume a density of pure Sargassum patches of 3.34 kg m−2 of wet weight35.

Martinique (French Indies)

In 2018, the French Geological Survey (BRGM) (www.brgm.fr) deployed an autonomous camera monitoring network in Martinique and Guadeloupe to improve knowledge and understanding of Sargassum strandings60,61. At several sites, an image processing system was implemented to automatically detect Sargassum and estimate its surface area. Accuracy of these surface estimates depends on the camera’s viewing angle; the approach can lead to underestimation. Here, we analyze two areas of interest in Martinique for which estimates of Sargassum area cover are available at two-hour intervals (from 8 AM to 4 PM) between 2021 and 2023. To estimate accumulated quantities and avoid counting the same biomass multiple times, we identified relative maxima in Sargassum coverage using a 8-day moving window. As illustrated in Fig. S2, this approach effectively detects stranding events (but it may likely miss some events during periods when multiple significant strandings occur within a single week). These events are then aggregated monthly to estimate total monthly strandings. One key uncertainty in comparison with model stranded biomass lies in the thickness or surface density of Sargassum aggregates. In the open ocean, a density of 3.34 kg m−2 (wet weight) is often used35 whereas on beaches, densities are significantly higher. For instance, in Puerto Morelos (Mexico), average densities of 20 kg m−2 (wet weight) have been recorded, with peaks reaching 60–80 kg m−2 in summer 201862. Coastal accumulations likely fall between these values. For Martinique’s coastal waters, in absence of measurements, we adopt a density of 10 kg m−2 in between offshore and beach estimates. Time series data from Le Francois Beach indicate monthly strandings ranging between 100 and 300 tons of wet biomass over a 200-meter stretch for both model estimates and observations (Fig. S3a). At Baie du Diamant (Figure S3b), where the coastline extends approximately 1500 m, both model and observed strandings range from 1000 to 2000 tons (wet weight) per summer month. These findings suggest that the seasonality and magnitude of strandings represented in the model in Martinique are consistent with observations at these locations.

Puerto Morelos (Quintana Roo, Mexico)

Several studies have assessed Sargassum strandings in this region through direct field measurements49, video camera monitoring48, and data collected from hotels26. Estimates derived from hotel collection data indicate average stranding volumes of 2000 to 7000 m2 of Sargassum per km of beach during the summers of 2018 and 201926. Ref49 report stranded quantities ranging from 500 to 1000 m2 (wet weight) per km for the same period. These differences highlight the uncertainties in estimating accumulated quantities, particularly as they do not account for nearshore sargassum accumulations, which can extend several tens of meters offshore48. Model-derived estimates for the summers of 2018 and 2019 in the Quintana Roo region range between 1000 and 5000 m2 (wet weight) per km (Fig. S4), which is in the range given in the literature26,49.

So, based on available data, our model appears to effectively represent the magnitude and seasonality of accumulated quantities along the coast.

Data availability

The stranding database described in this study will be made available on Zotero once published. The Sargassum areal coverage database was processed by AERIS/ICARE data center at the University of Lille and is available at Berline and Descloitres (2021). The BIO4 biogeochemical simulations are available at Mercator Ocean International (2023). GLORYS12 can be downloaded at https://data.marine.copernicus.eu.The Sargassum model is built upon the standard NEMO code (release 4.0.1, rev 11533), provided by Madec and the NEMO System Team63. The NEMO code modified to include the Sargassum physiology and transport is available in the Zenodo archive at Jouanno and Benshila64.

References

Gower, J., Young, E. & King, S. Satellite images suggest a new Sargassum source region in 2011. Remote Sens. Lett. 4, 764–773 (2013).

Wang, M. et al. The great Atlantic sargassum belt. Science 365, 83–87 (2019).

Johns, E. M. et al. The establishment of a pelagic Sargassum population in the tropical Atlantic: biological consequences of a basin-scale long distance dispersal event. Prog Oceanogr. 182, 102269 (2020).

Jouanno, J., Berthet, S., Muller-Karger, F., Aumont, O. & Sheinbaum, J. An extreme North Atlantic Oscillation event drove the pelagic sargassum tipping point. Commun. Earth Environ. 6, 95 (2025).

United Nations Environment Programme- Caribbean Environment Programme (UNEP-CEP). Sargassum white Paper – Turning the crisis into an opportunity. Ninth Meeting of the Scientific and Technical Advisory Committee (STAC) To the Protocol Concerning Specially Protected Areas and Wildlife (SPAW) in the Wider Caribbean Region, Kingston, Jamaica (2021).

Resiere, D. et al. Sargassum seaweed health menace in the Caribbean: clinical characteristics of a population exposed to hydrogen sulfide during the 2018 massive stranding. Clin. Toxicol. 59(3), 215–223 (2021).

Rodríguez-Martínez, R. E., Reali, M. Á. G., Torres-Conde, E. G. & Bates, M. N. Temporal and Spatial variation in hydrogen sulfide (H2S) emissions during holopelagic sargassum spp. Decomposition on beaches. Environ. Res. 247, 118235 (2024).

Devault, D. A. et al. Sargassum contamination and consequences for downstream uses: a review. J. Appl. Phycol. 33, 567–602 (2021).

Van Tussenbroek, B. I. et al. Severe impacts of brown tides caused by sargassum spp. On near-shore Caribbean seagrass communities. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 122(1–2), 272–281 (2017).

Hendy, I. W. et al. Climate-driven golden tides are reshaping coastal communities in Quintana Roo, Mexico. Clim. Change Ecol. 2, 100033 (2021).

Antonio-Martínez, F. et al. Leachate effects of pelagic sargassum spp. On larval swimming behavior of the coral acropora Palmata. Sci. Rep. 10(1), 3910 (2020).

DEAL Gestion des échouages de sargasses en Martinique. Avancées, perspectives Bureau du Comité de l’Eau et de la Biodiversité 18 juin 2020. Communication (2020).

Gower, J. & King, S. Distribution of floating Sargassum in the Gulf of Mexico and the Atlantic ocean mapped using MERIS. Int. J. Remote Sens. 32, 1917–1929 (2011).

Wang, M. & Hu, C. Mapping and quantifying Sargassum distribution and coverage in the central Western Atlantic using MODIS observations. Remote Sens. Environ. 183, 350–367 (2016).

Jouanno, J. et al. Skillful seasonal forecast of Sargassum proliferation in the Tropical Atlantic. Geophys. Res. Lett. 50, e2023GL105545 (2023).

Gower, J. & King, S. The distribution of pelagic sargassum observed with OLCI. Int. J. Remote Sens. 41(15), 5669–5679 (2020).

Berline, L. et al. Hindcasting the 2017 dispersal of Sargassum algae in the tropical North Atlantic. Mar. Pollut Bull. 158, 111431 (2020).

Marsh, R., Oxenford, H. A., Cox, S. A. L., Johnson, D. R. & Bellamy, J. Forecasting seasonal sargassum events across the tropical Atlantic: overview and challenges. Front. Mar. Sci. 9, 914501 (2022).

Trinanes, J., Putman, N. F., Goni, G., Hu, C. & Wang, M. Monitoring pelagic sargassum inundation potential for coastal communities. J. Oper. Oceanogr. 16(1), 48–59 (2023).

Wang, M. & Hu, C. Predicting sargassum blooms in the Caribbean sea from MODIS observations. Geophys. Res. Lett. 44, 3265–3273 (2017).

León-Pérez, M. C., Reisinger, A. S. & Gibeaut, J. C. Spatial-temporal dynamics of decaying stages of pelagic sargassum spp. Along shorelines in Puerto Rico using Google Earth engine. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 188, 114715 (2023).

Wang, M. & Hu, C. Satellite remote sensing of pelagic sargassum macroalgae: the power of high resolution and deep learning. Remote Sens. Environ. 264, 112631 (2021).

Arellano-Verdejo, J. & Lazcano-Hernandez, H. E. Cabanillas-Terán, N. ERISNet: deep neural network for sargassum detection along the coastline of the Mexican Caribbean. PeerJ 7, e6842 (2019).

Putman, N. F. et al. Improving satellite monitoring of coastal inundations of pelagic sargassum algae with wind and citizen science data. Aquat. Bot. 188, 103672 (2023).

Aranda, D. A., Enríquez Díaz, M. & Elías, V. Cooperación En El caribe ante El Sargazo. Rev. Acad. Mex Cienc. 71, 4 (2020).

Rodríguez-Martínez, R. E., Jordán-Dahlgren, E. & Hu, C. Spatio-temporal variability of pelagic sargassum landings on the Northern Mexican Caribbean. Remote Sens. Appl. Soc. Environ. 27, 100767 (2022).

Yaw Atiglo, D., Jayson-Quashigah, P. N., Sowah, W., Tompkins, E. L. & Addo, K. A. Misperception of drivers of risk alters willingness to adapt in the case of sargassum influxes in West Africa. Glob. Environ. Change 84, 102779 (2024).

Almela, V. D., Tompkins, E. L., Dash, J. & Tonon, T. Brown algae invasions and bloom events need routine monitoring for effective adaptation. Environ. Res. Lett. 19, 013003 (2024).

Jouanno, J. et al. A NEMO-based model of Sargassum distribution in the tropical Atlantic: description of the model and sensitivity analysis (NEMO-Sarg1.0). Geosci. Model Dev. 14(6), 4069–4086 (2021).

Andrade, C. A. & Barton, E. D. The Guajira upwelling system. Cont. Shelf Res. 25, 1003–1022 (2005).

Rueda-Roa, D., Ezer, T. & Muller-Karger, F. E. Description and mechanisms of the mid-year upwelling in the Southern Caribbean sea from remote sensing and local data. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 6, 36 (2018).

Rueda-Roa, D. T. & Muller-Karger, F. E. August. The Southern Caribbean Upwelling System: Sea surface temperature, wind forcing and chlorophyll concentration patterns. Deep Sea Res. Part I 78, 102–114 (2013).

Jouanno, J. & Sheinbaum, J. Heat balance and eddies in the Caribbean upwelling system. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 43(5), 1004–1014 (2013).

Muller-Karger, F. E., McClain, C. R., Fisher, T. R., Esaias, W. E. & Varela, R. Pigment distribution in the Caribbean Sea: observations from space. Prog. Oceanogr. 23, 23–69 (1989).

Wang, M. et al. Remote sensing of sargassum biomass, nutrients, and pigments. Geophys. Res. Lett. 45, 12359–12367 (2018).

Mclaughlin, S. & Cooper, J. A. G. A multi-scale coastal vulnerability index: A tool for coastal managers? Environ. Hazards. 9, 233–248 (2010).

Ahmed, M. A., Sridharan, B., Saha, N., Sannasiraj, S. A. & Kuiry, S. N. Assessment of coastal vulnerability for extreme events. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 82, 103341 (2022).

Mendoza, E. T. et al. Coastal flood vulnerability assessment, a satellite remote sensing and modeling approach. Remote Sens. Applications: Soc. Environ. 29, 100923 (2023).

Dada, O. A., Almar, R. & Morand, P. Coastal vulnerability assessment of the West African Coast to flooding and erosion. Sci. Rep. 14, 890 (2024).

Rosellón-Druker et al. Local ecological knowledge and perception of the causes, impacts and effects of sargassum massive influxes: a binational approach. Ecosyst. People. 19(1), 2253317 (2023).

WorldFish Centre, U. N. E. P. W. C. M. C. & IRD. WRI, TNC Global distribution of warm-water coral reefs, compiled from multiple sources including the Millennium Coral Reef Mapping Project. Version 4.0. Includes contributions from IMaRS-USF and IMaRS-USF (2005) and Spalding et al. (2001). Cambridge (UK): UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre. http://data.unep-wcmc.org/datasets/ (2005).

Athanasiou, P. et al. Global Coastal Characteristics (GCC): A global dataset of geophysical, hydrodynamic, and socioeconomic coastal indicators. Earth System Science Data Discussions 1–32 (2023).

Adamiak, C. & Szyda, B. Combining conventional statistics and big data to map global tourism destinations before COVID-19. J. Travel Res. 61, 1848–1871 (2022).

Ramlogan, N. R., McConney, P. & Oxenford, H. A. Socio-economic Impacts of Sargassum Influx Events on the Fishery Sector of Barbados. Centre for Resource Management and Environmental Studies (CERMES), University of the West Indies 86 (2017).

Jenks, G. F. Optimal Data Classification for Choropleth Maps. Occasional Paper No. 2 (Department of Geography, University of Kansas, 1977).

Lara-Hernández, J. A. et al. Sargassum transport towards Mexican Caribbean Shores: numerical modeling for research and forecasting. J. Mar. Syst. 241, 103923 (2024).

Van Tussenbroek, B. I. et al. Monitoring drift and associated biodiversity of nearshore rafts of holopelagic sargassum spp. In the Mexican Caribbean. Aquat. Bot. 195, 103792 (2024).

Rutten, J. et al. Beaching and natural removal dynamics of pelagic sargassum in a fringing-reef lagoon. J. Geophys. Res. 126(11), e2021JC017636 (2021).

Vázquez-Delfín, E., Robledo, D. & Freile-Pelegrín, Y. Temporal characterization of sargassum (Sargassaceae, Phaeophyceae) strandings in a sandy beach of Quintana Roo, Mexico: ecological implications for coastal ecosystems and management. Thalassas 40, 1053–1067 (2024).

Gower, J., Hu, C., Borstad, G. & King, S. Ocean color satellites show extensive lines of floating Sargassum in the Gulf of Mexico. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 44, 3619–3625 (2006).

Jouanno, J. et al. Evolution of the riverine nutrient export to the tropical Atlantic over the last 15 years: is there a link with Sargassum proliferation? Environ. Res. Lett. 16(3), 034042 (2021).

Zhang, Y. et al. Pelagic sargassum in the Gulf of Mexico driven by ocean currents and eddies. Harmful Algae. 132, 102566 (2024).

Berline, L. & Descloitres, J. Cartes de répartition des couvertures de Sargasses dérivées de MODIS sur l’Atlantique. AERIS/ ICARE - CNES/TOSCA (2021).

Putman, N. F., Lumpkin, R., Olascoaga, M. J., Trinanes, J. & Goni, G. J. Improving transport predictions of pelagic sargassum. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 529, 151398 (2020).

Podlejski, W., Berline, L., Nerini, D., Doglioli, A. & Lett, C. A new sargassum drift model derived from features tracking in MODIS images. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 188, 114629 (2023).

Olascoaga, M. J. et al. Physics-informed laboratory Estimation of Sargassum windage. Phys. Fluids. 35, 111702 (2023).

Lellouche, J. M. et al. The copernicus global 1/12° oceanic and sea ice GLORYS12 reanalysis. Front. Earth Sci. 9, 698876 (2021).

Berthet, S. et al. Evaluation of an online grid-coarsening algorithm in a global eddy-admitting ocean biogeochemical model. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 11, 1759–1783 (2019).

Salter, M. A., Rodríguez-Martínez, R. E., Álvarez-Filip, L., Jordán-Dahlgren, E. & Perry, C. T.Pelagic sargassum as an emerging vector of high rate carbonate sediment import to tropical Atlantic coastlines. Glob. Planet Change 195, 103332 (2020).

Bouvier, C. Suivi des échouages de sargasses sur le littoral de la Martinique (2020–2022). Rapport BRGM/RP-72256-FR. Access (2022). https://infoterre.brgm.fr/rapports/RP-73581-FR.pdf.

Bouvier, C. Suivi des échouages de sargasses sur le littoral de la Martinique (2022–2023). Rapport final V1. BRGM/RP-73581-FR (2024).

García-Sánchez, M. et al. Temporal changes in the composition and biomass of beached pelagic sargassum species in the Mexican Caribbean. Aquat. Bot. 167, 103275 (2020).

Madec, G. & the NEMO System Team. and NEMO Ocean Engine Reference Manual, Zenodo, [Software]: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8167700 (2023). (last accessed 01 APR 2023).

Jouanno, J. & Benshila, R. Sargassum distribution model based on the NEMO ocean modelling platform (0.0). Zenodo. [software]. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4275900 (last access 01/14/2025) (2025).

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge AERIS/ICARE for providing MODIS Sargassum detections, and acknowledge BRGM and C. Bouvier for sharing video data and Sargassum cover estimates at Martinique stranding sites Le Diamant and Le Francois.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JJ conceived the study , produced the datasets, the figures and drafted the manuscript. GM and RB participated to the development of the Sargassum model. All the authors have participated to the interpretation of the data and writing of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jouanno, J., Almar, R., Muller-Karger, F. et al. Socio-ecological vulnerability assessment to Sargassum arrivals. Sci Rep 15, 9998 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-94475-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-94475-3