Abstract

In this in vitro study, indentation cracks in orthogonal directions and different areas on bovine enamel occlusal surface were analyzed by quantitative characterization of crack number, length and displacement, aiming to reveal the correlation between the microstructure and crack growth behavior of bovine enamel. Results showed that the cracks induced by indenting on the enamel occlusal surface tend to initiate at the rod/inter-rod boundaries. The rod/inter-rod hydroxyapatite (HAP) nanofibers and associated decussation cause a preferential extension of the cracks along the rod/inter-rod interface by inducing crack deflection, bifurcation, and bridging. In addition, the inter-rod nano-structure, consisting of orderly assembled HAP nanofibers, leads to an additional toughening mechanism of zig-zag cracking to hinder crack growth within the narrow inter-rod region. In summary, the unique microstructural architecture of bovine enamel, especially the decussation within rod/inter-rod nanofibers, plays an important role in functionally guiding cracks on bovine enamel occlusal surface to grow along the interface between rod and inter-rod rather than across the inter-rod enamel. The anisotropic crack growth behavior helps prevent bovine enamel from substantial fracture and chipping induced wear. These findings extend the understanding of the toughening mechanisms of mammalian enamel.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Enamel, the outer cover of most mammalian teeth, is composed mainly of inorganic substances (mostly hydroxyapatite, HAP) and minor organic matter (mostly proteins) plus water1,2, and it has a microstructure consisting of assembled enamel rods and inter-rod features3,4,5. As the hardest tissue in the body, enamel also possesses outstanding fracture toughness5,6,7.

The toughening mechanisms of mammalian enamel, which include crack bridging, micro-cracking, crack bifurcation, and crack deflection6,7,8,9, are widely accepted to be related to the hierarchical microstructure and minor protein component present in enamel. The proteins facilitate crack growth deflection behavior, and thus was considered a significant toughening phase in enamel in previous studies10,11,12. In addition, the fracture resistance of enamel is inhomogeneous and spatially anisotropic as cracking more readily extends in a less densely packed microstructure, and thus it is considered that the orientation of enamel rods influences crack propagation13,14. The preferred path of crack propagation is along the protein-rich rod/inter-rod interface15,16,17,18,19.

Generally, according to feeding habits, mammals can be classified as herbivorous, carnivorous and omnivorous. As shown in Fig. 1, canine (carnivore) and porcine (omnivore) enamel has a microstructure of hard keyhole-like rods (~ 5 μm diameter) embedded in thin higher protein containing inter-rod enamel (~ 1 μm thickness). The inter-rod enamel is inferior to the rods with respect to its mechanical properties including hardness and elastic modulus5,20, and appears to play a dominant toughening role in providing the crack arresting ability of enamel15. In the case of bovine enamel, a typical herbivore enamel, elongated semi-keyhole-like enamel rods (1.5–3 μm in thickness and 4–8 μm in width) and sheet-like inter-rod enamel (0.1–1 μm in thickness) lamellarly assemble together (Fig. 1), and the hardness and elastic modulus of the inter-rod enamel are not lower, but even slightly higher than that of the rods5. This means that the toughening mechanism of soft inter-rod enamel is likely absent in bovine enamel. Despite the documented extensive chewing time that reaches 10 h per day and places bovine teeth, especially molars, undoubtedly at risk of fatigue and fracture, however, the molars are barely damaged by cracking or chipping21. Hence, the crack behavior of bovine enamel has attracted much attention in the past decade22.

For omnivore and carnivore enamel, HAP nanofibers (~ 60 nm diameter, assembled from ~ 20 nm crystallites) in the rod and inter-rod regions, although at an angle, are basically oriented along the direction of the rod axis5,12,23, while the microstructure of bovine enamel is characterized with the rod/inter-rod HAP nanofibers in decussation5,24, as shown in Fig. 1. Results of the studies by Ang et al. showed that the rod/inter-rod boundaries in bovine enamel have the potential to hinder crack propagation due to a significant change in HAP nanofiber orientation6. Xiao et al. compared the crack behavior on the occlusal surfaces of bovine and canine molar enamels and confirmed that for bovine enamel, the HAP nanofibers in decussation enhances crack propagation resistance5. Although the aforementioned studies demonstrate that the crack growth behavior of bovine enamel is closely related to the unique alignment organization of HAP nanofibers, the specific crack resistance mechanism(s) of the HAP nanofibers is far from clear.

Morphological images illustrating bovine (herbivore), porcine (omnivore) and canine (carnivore) enamel microstructures5. R and IR designate enamel rod and inter-rod enamel, respectively.

In this study, the crack growth behavior of bovine enamel was investigated using nano-indentation techniques and various microscopic examination procedures. The indentation cracks in different directions/areas on the enamel occlusal surface were analyzed by quantitative characterization of crack number, crack length and crack surface displacement. The aim of this study is to reveal the correlation between the crack growth behavior and the micro-nano structure of bovine enamel, and then extend the understanding of the toughening mechanisms of mammalian enamel.

Materials and methods

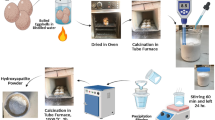

Sample collection and Preparation

Enamel samples used in this study were prepared from freshly extracted bovine posterior molars of male cattle aged from 10 to 14 months collected from a local abattoir. All teeth were caries-free and no obvious scratches and cracks on their surfaces, and they were kept in deionized water at 4 ºC before using. The collection of all teeth was in conformity with the ethical standards of the Chinese Psychological Society.

Depending on tooth shape, each molar was cut into 5–8 parts using a diamond saw. Efforts were made to ensure the size of each part larger than 5 × 5 × 5 mm3to support the crack advance according to the models based on Palmqvist and median/half-penny cracks in the Vickers indentation fracture technique25. A total of 40 parts were embedded vertically in a stainless-steel mold with denture acrylic resin to prepare the enamel samples with the occlusal surface exposed. The embedded blocks were ground and polished to obtain a flat testing surface. Detailed preparation methods were described elsewhere26. The average surface roughness Rawas controlled to be no more than 0.02 μm using profilometer (TALYSURF6, England) over a 1.0 × 1.0 mm2 area. Only 0.2–0.3 mm in height was ground and polished off for each sample. Thus, the obtained testing surface was similar to the original occlusal surface of enamel in the mouth. Considering that local overheating causes tooth dehydration and changes in the microstructure and composition of teeth, the whole process of sample preparation including cutting, grinding, and polishing, was conducted under a water-cooling condition. All teeth and polished enamel samples were stored in 4 ºC distilled water to avoid dehydration before testing.

A total of 40 enamel samples were prepared. Four samples were randomly selected to characterize the surface microstructures of bovine enamel by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) (INSPECT F, FEI, England), which were etched for 10 min with 0.001 mol/L citric acid solution (pH = 3.2) before SEM examination. Remaining samples were used to characterize crack growth behavior.

Crack growth behavior characterization

Cracks on enamel samples were induced by indenting using the high load mode in a nano-indenter (G200, Keysight, USA). A Vickers diamond tip with a tip radius of 20 nm was used, and the applied normal load was 1.5 N. The diagonals of the Vickers indenter were aligned parallel and perpendicular to the rod structure of the enamel. A total of 36 samples were used, and on the exposed enamel surface of each sample, 8 indentations were made in the outer and inner areas, respectively, see Fig. 2. After indenting, the full view of each indentation was immediately examined by a laser scanning confocal microscopy (LSCM) (VK-X1000, Keyence, Japan) to measure the number and length of induced cracks. Subsequently, the enamel samples were etched for 20 s with 0.001 mol/L citric acid solution (pH = 3.2) to expose the microstructure of enamel, and then they were examined successively using the LCSM, atomic force microscopy (AFM) (Cypher, Oxford Instruments Asylum Research, England), and SEM to observe the crack growing path.

Previous studies commonly characterized pointed indentation induced cracks based upon residual crack wall displacement6,27,28, which is represented by the height difference (HD) and/or the crack opening displacement (COD) between two opposing crack walls, as shown in Fig. 3a. In this study, three-dimensional AFM topographical images of cracks were obtained in tapping mode using a silicon tip with a radius of 7 nm (AC160TSA-R3, Oxford Instruments Asylum Research, England) and applying a scanning frequency of less than 1 Hz. Based on the profiles of the crack sections at the desired positions, the associated HD and COD were measured (Fig. 3b). Generally, the HD and COD of crack are largest at the initiation location and close to zero at the termination location. For each crack, the decreasing rates of HD and COD were calculated using the following Eqs. (1) and (2), respectively:

where VHD is the rate of decrease of HD, VCOD is the rate of decrease of COD, ΔHD and ΔCOD are the HD and COD of crack initiation location at the edge of the indenter contact diagonal, and L is the crack length. By taking into account crack length and the HD and COD of cracks, VHD and VCOD allow for an accurate assessment of crack resistance. To identify the desired positions, the samples used to do HD/COD measurements were prior etched for 20 s with 0.001 mol/L citric acid solution. Results of our preliminary experiments demonstrated that such etch treatment has no obvious influence on the crack profile.

Results

The microstructure of bovine enamel outer area was characterized as the semi-keyhole-like enamel rods and the sheet-like inter-rod enamel laminated together and the rod/inter-rod HAP nanofibers displaying decussation (Fig. 4). The nanofibers in the rods were perpendicular to the occlusal surface, whereas the nanofibers in the inter-rod enamel were parallel to the occlusal surface and had a compact nano-structure.

The indentations on bovine enamel outer area were observed firstly by LSCM, and typical micrographs are shown in Fig. 5. Imaging of the samples without etching clearly illustrated the number and length of the cracks induced by indenting, and the correlation of the crack growing path with enamel microstructure was more readily observed after etching. Two types of cracks were induced by indenting: one propagated along the rod/inter-rod boundaries and were referred to as “parallel” cracks, another propagated across the inter-rod and were referred to as “orthogonal” cracks. It was observed that more parallel cracks were induced and they tended to propagate farther, compared with the orthogonal cracks.

The bovine enamel inner area was also characterized as a lamellar structure with rod/inter-rod HAP nanofibers displaying decussation, but the inter-rod nanofibers were inclined a little relative to the occlusal surface (Fig. 6a). Different from the bovine enamel outer area, the orthogonal cracks on the bovine enamel inner area tended to extensively propagate, as shown in Fig. 6b.

A total of 36 samples were examined by LCSM, and statistical analysis of average length and number of the induced cracks per indentation are shown in Fig. 7. The length and number of the cracks, either parallel or orthogonal, were larger on the bovine enamel inner area than on the outer area, and they were significantly larger for the parallel cracks than for the orthogonal cracks. The crack length difference between parallel and orthogonal cracks in the inner area decreased but the crack number difference increased, as compared with the outer area.

To more directly demonstrate the growth behavior of cracks, further imaging by AFM enabled the HD and COD of each crack, and then their decreasing rates, VHD and VCOD, to be calculated. Average VHD and VCOD obtained from 36 samples are shown in Fig. 8. It is seen that the average VHD and VCOD were similar for the parallel and orthogonal cracks in the bovine enamel inner area, but they significantly increased for the orthogonal cracks in the outer area. Noting that in the outer area, the orthogonal cracks exhibited extraordinarily high VHD and VCOD; thus, the variations of the crack HD and COD with propagation distance were analyzed by measuring the crack HD and COD at the locations where the cracks intersected the rod/inter-rod boundaries. Parallel cracks were used as control, where the HD and COD were measured at 1 μm intervals. As shown in Fig. 9, compared with those of the parallel cracks, the HD and COD of the orthogonal cracks decreased faster with propagation distance, especially COD showed a greater decrease in the inter-rod region. It was also found that the orthogonal cracks deflected significantly as they entered the inter-rod region (Fig. 9a). Follow-up SEM imagery in Fig. 10 evinced that when entering/exiting the inter-rod region, the orthogonal and parallel cracks deflected and bifurcated, thereby leading to crack bridging. It is noticeable that for the orthogonal cracks, crack zig-zag behavior also occurred.

Discussion

It has been widely accepted that bovine enamel has outstanding fracture toughness6,12,16,22,29. As a typical example of herbivore enamel, bovine enamel has a unique micro-nano structure characterized as lamellarly assembled enamel rods and sheet-like inter-rod enamel, and the rod/inter-rod nanofibers in decussation (Fig. 4). Moreover, the inter-rod region appears to have a compact microstructure consisting of orderly assembled HAP nanofibers. In this study, the number, length, and crack-wall displacement of the indentation cracks in orthogonal directions and different areas on bovine enamel occlusal surface were quantitatively characterized and compared, aiming to elucidate the correlation between the crack behavior and micro-nano structure of bovine enamel.

Anisotropy of crack growth behavior of bovine enamel on the occlusal surface is evident. As shown in Figs. 5, 7, 8 and 9, indenting in bovine enamel outer area induced both orthogonal and parallel cracks, but the number and length of the parallel cracks were much larger, accompanied by much lower VHD and VCOD. This observation suggests that it is very difficult for the orthogonal cracks to the rod structure to propagate on bovine enamel occlusal surface, whereas the propagation of parallel cracks is relatively easy, which is consistent with previous studies6,16. Due to the microstructure of enamel consisting of sheet-like inter-rod enamel laminated together with the rods (Fig. 4), the growth of orthogonal cracks needs to traverse through the rod/inter-rod boundaries and inter-rod regions. Note that an obvious change occurs to the HAP nanofiber orientation in the rod/inter-rod boundaries. The HAP nanofibers in the rods are perpendicular to the occlusal surface, whereas the fibers in the inter-rod enamel tend to be parallel to the occlusal surface (Fig. 4), that is, the rod nanofibers are decussated with the inter-rod nanofibers. Hence, when developing, the parallel cracks predominantly extend at the rod/inter-rod interface and cross any bridges almost parallel to the HAP nanofiber orientations, while the orthogonal cracks have to meet the inter-rod structure at 90 degrees and there are many such bridges to cross. Obviously, the energy required to extend the parallel cracks is far less than that required to fracture all the nanofibers perpendicular to the propagation direction of the orthogonal cracks. In addition, due to the existence of the interface between HAP nanofibers, the cracks tend to search for a weak site rather than break the next nanofiber to further extend12. As shown in Fig. 10, the cracks were significantly deflected and bifurcated when entering/exiting the inter-rod enamel, resulting in crack bridging. It implies that the rod/inter-rod nanofibers in decussation assist the deflection and bridging of cracks. Previous studies found that for hard biological materials such as shell and enamel, the change in fiber orientation at the micro-nano interface causes a preferential propagation of cracks along the interface and increase the possibility of crack bifurcating and bridging12,30. Evidently, in bovine enamel the rod/inter-rod nanofibers in decussation play an important role in hindering the growth of orthogonal cracks.

It has been widely accepted that the synergistic toughness of nacre and seashell is closely associated with their internal staggered architecture31,32,33,34, which retard crack propagation through inducing crack zig-zag behaviour, a form of crack deflection manifested with crack direction changing more frequently34,35. The SEM images in Fig. 10 demonstrate crack zig-zag features which occurred when the orthogonal cracks propagated through the inter-rod region. Note that in the present study, no crack zig-zags were observed in the rod region. Thus, it could be inferred that a mechanical function of the inter-rod nano-structure consisting of the orderly assembled HAP nanofibers is related to a toughening mechanism of crack zig-zag so as to encumber cracks traversing the inter-rod region.

Clearly, it was the unique micro-nano structure that affords bovine enamel with anisotropic crack growth behavior. The cracks on bovine enamel occlusal surface grow along the rod/inter-rod boundaries rather than across the inter-rod enamel. Interestingly, we further found that the anisotropy of crack growth is reduced with the indentation site changing from the outer area to inner area on bovine enamel occlusal surface. As shown in Figs. 6b, 7 and 8, in the inner area, the number of the orthogonal cracks around the indentation was still much smaller than that of the parallel cracks, but the differences in crack length and HD/COD decreasing rates between the two cracks decreased. The reduction of the anisotropy is related to the change of HAP nanofiber alignment organization. As a natural biological material, bovine enamel is characterized with property gradients22. In the enamel inner area close to the enamel-dentin junction, the inter-rod nanofibers tend to be approximately perpendicular to the enamel surface (Fig. 6a). This means that the difficulty for cracks to penetrate the inter-rod enamel is decreased. As a result, in the bovine enamel inner area, it is easy for the orthogonal cracks to traverse through the rod/inter-rod boundaries and the inter-rod regions, thereby resulting in increased crack length and decreased VHD and VCOD (Figs. 7a and 8). As shown in Fig. 6a, although the HAP nanofiber alignment changes, the enamel in the inner area still has a lamellar rod/inter-rod microstructure similar to that of the outer area. That is, the rod/inter-rod interface still acts as weak interface in the inner area to guide cracks to initiate and propagate. In 2010, Bechtle et al. evaluated the crack resistance of enamel using bending experiments16, and the results showed that it is harder for cracks to propagate from the outer to inner enamel than from the inner to outer enamel. However, in the present study, the number and length of indentation cracks were increased in the bovine enamel inner area, as compared to the outer area.

The anisotropic crack growth behavior of bovine enamel is associated with the structural characteristics of bovine molar occlusal surface. For most bovine molars, the dentin, alongside with the enamel, is exposed on the occlusal surface. As shown in Fig. 11, on the occlusal surface, from the outer to inner enamel, the increasing organic content, decreasing mechanical properties, and twisting rod/inter-rod boundaries provide a positive effect for dissipating crack energy16,22,36. In addition, most cracks growing inward are eventually arrested before the enamel-dentin junction7,29,37. As a result, parallel cracks, although easy to initiate and propagate, cannot bring catastrophic damage. Meanwhile, the growth of orthogonal cracks is effectively hindered due to the unique micro-nano structure of enamel, thereby preventing the formation of circumferential cracks. Clearly, the anisotropic crack growth behavior mediated by bovine enamel micro-nano structure helps prevent the enamel from fracture and chipping, which is adapted to the feeding habit of herbivores. Thus, bovine molars, although suffering a long chewing time, are barely damaged by cracking or chipping fracture.

The results of this study showed that the microstructural architecture of bovine enamel, especially the rod/inter-rod HAP nanofibers in decussation, contributes to the preferential propagation of cracks along the interface between rod and inter-rod by inducing crack deflection, bifurcation, bridging, and zig-zag behavior. The anisotropic crack growth behavior protects bovine enamel from substantial fracture and chipping induced wear. Although the indentation approach used in the present study to induce enamel crack cannot fully simulate intraoral chewing actions, these results, to the best of our knowledge, represent a detailed analysis of the relationship between the microstructural architecture of bovine enamel and its crack growth behaviour. The findings of the present study reinforce the idea that enamel anisotropy and hierarchical structure are key to its exceptional toughness. In practice, many medical devices and mechanical components made from hard materials are at risk of fracture or chipping in the service conditions. For example, ceramics are widely used in dental clinic because of their excellent mechanical properties, good biocompatibility, and satisfactory aesthetics, but they are short of toughness compared to natural enamel, thus often facing premature failure due to fracture and chipping38; cutters in tunnel boring machines, which are made of high hardness metals, experience serious wear and fracture when encountering hard rocks such as granites and quartzites39. Theoretically, simulating the anti-crack structural features of natural materials is a promising strategy to improve the toughness of hard materials. Noting that, crack resistance in natural materials such as dental enamel is highly related to microstructural architecture and the amount of mineralized tissue and its interconnection with the protein. Therefore, future research will explore how variations in HAP nanofiber orientation and composition influence crack behaviour in other types of enamel or similar biological materials.

Conclusions

The indentation crack growth behavior on bovine enamel occlusal surface was investigated based on quantitative characterizations of crack number, length and displacement in this study. Within the limits of our research, conclusions can be summarized as follows:

(1) On the bovine enamel occlusal surface with the lamellar microstructure consisting of rods and sheet-like inter-rod, the indentation cracks tend to initiate and propagate along the rod/inter-rod interface and hardly traverse the inter-rod enamel due to the toughening mechanisms of crack deflection, bifurcation, bridging, and crack zig-zag that are induced by the rod/inter-rod HAP nanofibers in decussation.

(2) The rod/inter-rod HAP nanofibers in decussation plays an important role in functionally guiding the cracks on bovine enamel occlusal surface to grow along the rod/inter-rod interface preferentially. The anisotropic crack growth behavior helps prevent the enamel from fracture and chipping.

Data availability

The data are provided in the manuscript. The raw/processed data required to reproduce these findings are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Min, B. M. in Oral Biochemistry, Ch. Enamel, 7–28Springer, (2023).

Sarna-Boś, K. et al. Insight into structural and chemical profile/composition of powdered enamel and dentine in different types of permanent human teeth. Micron, 103608 (2024).

Serebryany, V., Kolyanova, A., Mikhailova, A. & Shamray, V. Quantitative texture study of the tooth enamel. Crystallogr. Rep. 68, 1159–1165 (2023).

He, L. H. & Swain, M. V. Understanding the mechanical behaviour of human enamel from its structural and compositional characteristics. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 1, 18–29 (2008).

Xiao, H. et al. Research of the role of microstructure in the wear mechanism of canine and bovine enamel. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 92, 33–39 (2019).

Ang, S. F., Schulz, A., Fernandes, R. P. & Schneider, G. A. Sub-10-micrometer toughening and crack tip toughness of dental enamel. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 4, 423–432 (2011).

Bajaj, D. & Arola, D. Role of Prism decussation on fatigue crack growth and fracture of human enamel. Acta Biomater. 5, 3045–3056 (2009).

Yahyazadehfar, M. et al. On the mechanics of fatigue and fracture in teeth. Appl. Mech. Rev. 66 (2014).

Kruzic, J. J., Hoffman, M. & Arsecularatne, J. A. Fatigue and wear of human tooth enamel: A review. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 138, 105574 (2023).

White, S. et al. Biological organization of hydroxyapatite crystallites into a fibrous continuum toughens and controls anisotropy in human enamel. J. Dent. Res. 80, 321–326 (2001).

Lei, L., Zheng, L., Xiao, H., Zheng, J. & Zhou, Z. Wear mechanism of human tooth enamel: the role of interfacial protein bonding between HA crystals. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 110, 103845 (2020).

Koldehoff, J., Swain, M. V. & Schneider, G. A. Influence of water and protein content on the creep behavior in dental enamel. Acta Biomater. 158, 393–411 (2023).

Xie, Z., Swain, M., Munroe, P. & Hoffman, M. On the critical parameters that regulate the deformation behaviour of tooth enamel. Biomaterials 29, 2697–2703 (2008).

Wilmers, J. & Bargmann, S. Nature’s design solutions in dental enamel: uniting high strength and extreme damage resistance. Acta Biomater. 107, 1–24 (2020).

Bajaj, D., Nazari, A., Eidelman, N. & Arola, D. D. A comparison of fatigue crack growth in human enamel and hydroxyapatite. Biomaterials 29, 4847–4854 (2008).

Bechtle, S., Habelitz, S., Klocke, A., Fett, T. & Schneider, G. A. The fracture behaviour of dental enamel. Biomaterials 31, 375–384 (2010).

Yahyazadehfar, M., Bajaj, D. & Arola, D. D. Hidden contributions of the enamel rods on the fracture resistance of human teeth. Acta Biomater. 9, 4806–4814 (2013).

Beniash, E. et al. The hidden structure of human enamel. Nat. Commun. 10, 4383 (2019).

Ramadoss, R., Padmanaban, R. & Subramanian, B. Role of bioglass in enamel remineralization: existing strategies and future prospects—A narrative review. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part. B. 110, 45–66 (2022).

Habelitz, S., Marshall, S., Marshall Jr, G. & Balooch, M. Mechanical properties of human dental enamel on the nanometre scale. Arch. Oral Biol. 46, 173–183 (2001).

Fadden, A. et al. Dental pathology in conventionally fed and pasture managed dairy cattle. Vet. Rec. 178, 19–19 (2016).

Yilmaz et al. Influence of structural hierarchy on the fracture behaviour of tooth enamel. Philos. Trans. R Soc. A. 373, 20140130 (2015).

O’Brien, S., Keown, A. J., Constantino, P., Xie, Z. & Bush, M. B. Revealing the structural and mechanical characteristics of ovine teeth. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 30, 176–185 (2014).

Wang, C., Li, Y., Wang, X., Zhang, L. & Fu, B. The enamel microstructures of bovine mandibular incisors. Anat. Rec. 295, 1698–1706 (2012).

Moradkhani, A., Panahizadeh, V. & Hoseinpour, M. Indentation fracture resistance of brittle materials using irregular cracks: A review. Heliyon (2023).

Zheng, J. et al. In vitro study on the wear behaviour of human tooth enamel in citric acid solution. Wear 271, 2313–2321 (2011).

Anderson, T. L. Fracture Mechanics: Fundamentals and Applications (CRC, 2017).

Meschke, F., Raddatz, O., Kolleck, A. & Schneider, G. A. R-curve behavior and crack‐closure stresses in barium titanate and (Mg, Y)‐PSZ ceramics. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 83, 353–361 (2000).

Bechtle, S., Fett, T., Rizzi, G., Habelitz, S. & Schneider, G. A. Mixed-mode stress intensity factors for kink cracks with finite kink length loaded in tension and bending. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 3, 303–312 (2010).

Liu, S. et al. On fracture behavior of inner enamel: a numerical study. Appl. Math. Mech. 44, 931–940 (2023).

Barthelat, F. & Espinosa, H. An experimental investigation of deformation and fracture of nacre–mother of Pearl. Exp. Mech. 47, 311–324 (2007).

Gao, H., Ji, B., Jäger, I. L., Arzt, E. & Fratzl, P. Materials become insensitive to flaws at nanoscale: lessons from nature. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100, 5597–5600 (2003).

Wei, J. et al. Bioinspired additive manufacturing of hierarchical materials: from biostructures to functions. Research 6, 0164 (2023).

Sun, J. & Bhushan, B. Hierarchical structure and mechanical properties of Nacre: a review. RSC Adv. 2, 7617–7632 (2012).

Song, J., Fan, C., Ma, H., Liang, L. & Wei, Y. Crack Deflection occurs by constrained microcracking in Nacre. Acta Mech. Sin. 34, 143–150 (2018).

Hegedűs, M. et al. Gradient structural anisotropy of dental enamel is optimized for enhanced mechanical behaviour. Mater. Des. 234, 112369 (2023).

Bechtle, S. et al. Crack arrest within teeth at the dentinoenamel junction caused by elastic modulus mismatch. Biomaterials 31, 4238–4247 (2010).

Valandro, L. F., Cadore-Rodrigues, A. C., Dapieve, K. S., Machry, R. V. & Pereira, G. K. R. A brief review on fatigue test of ceramic and some related matters in dentistry. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 138, 105607 (2023).

Zhang, H., Liu, S. & Xiao, H. Tribological properties of sliding quartz sand particle and shale rock contact under water and Guar gum aqueous solution in hydraulic fracturing. Tribo Int. 129, 416–426 (2019).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (52075459), Sichuan Science and Technology Program (No. 2023NSFSC0867), and the 111 Project (B20008). The authors extend their sincere appreciation to Dr. Joseph A. Arsecularatne, Prof. Michael V. Swain, and Yuanyuan Mei for their invaluable assistance throughout the process of writing and refining the manuscript.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Sichuan Science and Technology Program (No. 2023NSFSC0867).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Heng Xiao: conceptualization, methodology, investigation, visualization, formal analysis, writing original draft. Lei Lei: methodology, validation, data curation, writing review & editing. Michael V Swain and Yuanyuan Mei: writing review & editing. Jing Zheng: project administration, supervision, funding acquisition, writing review & editing. Zhongrong Zhou: funding acquisition.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xiao, H., Lei, L., Zheng, J. et al. Quantitative characterization of indentation initiated crack growth in bovine enamel. Sci Rep 15, 9405 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-94536-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-94536-7