Abstract

Microsecond pulsed electric field (µsPEF) is a newer treatment modality to replace catheter ablation treatment of Atrial fibrillation (AF) due to its fewer side effects. This study aims to find out experimental parameters that effectively induce cardiomyocyte death and the precise mechanisms for microsecond pulsed electric fields (µsPEFs) ablation of cardiomyocytes. CCK8 and flow apoptosis analysis were employed to examine the effects of different µsPEFs on cardiomyocytes in vitro. The mechanisms by which the µsPEFs ablation works were explored through a combination of transcriptome study, transmission electron microscope (TEM) observation of mitochondria, pathway enrichment analysis, and interaction network analysis. In vivo experiments on mice involving HE, Masson, TUNEL and Immunofluorescence staining examinations were conducted to confirm the in vitro experimental results. When more than 30 pulses were applied, a continuous decline in post-ablation relative cell activity was observed, decreasing from 0.36 at 3 h to 0.13 (p < 0.01) at 48 h. Notably, at a voltage of 1500 V/cm and a pulse count of 50, the apoptosis rate exceeded 95%, coupled with a more stable and consistent cell ablation. Following ablation, a notable upregulation in mitochondria-related transcription levels was observed, accompanied by mitochondrial membrane disruption and an increase in Cytochrome C levels. Within a certain range, an increase in voltage and number of electric pulses corresponded to a greater quantity of cell mortality in the ablation zone. The µsPEFs induced cell injury by impairing mitochondrial function and potentially triggering the mitochondrial apoptosis pathway.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most frequent cardiac arrhythmia1 that affects approximately 33 million people worldwide and over 3 million in the United States2. The incidence and prevalence of AF are still rising3, and it has been estimated that 6–12 million people worldwide will suffer this condition in the US by 2050 and 17.9 million people in Europe by 20601. AF represents a significant risk factor for ischemic stroke4 and provokes important economic burden, along with considerable morbidity and mortality1. On the electrocardiogram (ECG), AF is characterized by irregular R-R intervals and distinct P waves5. It is frequently associated with pathological atrial myocardial dysfunction and remodeling6, leading to irregular contractions of atrial cardiomyocytes and resulting in various symptoms, including an irregular heart rate, palpitations, dizziness, shortness of breath, and tiredness7. Although antiarrhythmic drugs are useful, AF ablation has become a primary therapeutic approach, with ongoing advancements in safety and efficacy2.

Pulsed electric field ablation (PEF) is an emerging treatment method for AF that creates non-thermal cardiac tissue lesions through irreversible electroporation, thus offering advantages over traditional catheter ablation methods8. PEF has been successfully applied in the treatment of various diseases, including liver cancer, pancreatic cancer, ovarian cancer, osteosarcoma, bronchial inflammation, and knee arthritis9,10,11,12,13,14. The most important benefit of PEF lies in its ability to selectively eliminate cells without causing substantial protein denaturation or tissue damage8, thus enhancing safety without compromising cardiomyocyte ablation efficacy15. Moreover, ultra-rapid electrical fields, specifically microsecond pulsed electric fields (µsPEFs), are applied to target tissue during the process of ablation, reducing both fluoroscopy and ablation times16. Two types of pulses are used for ablation: longer, monopolar pulses (50–100 µs), considered as a non-thermal method, and shorter, bipolar pulses (< 10 µs), known as HFIRE pulses, which can cause fewer muscle contractions17. Furthermore, the differential sensitivity between cardiomyocytes and other non-target tissues may help mitigate the risk of collateral damage to structures like the esophagus and phrenic nerve, which are susceptible to injury during radiofrequency ablation and cryo-balloon ablation16,18,19,20. However, beyond electroporation, the mechanisms governing cell death by the electric field remain elusive21. In particular, there is a limited number of reports on the voltage amplitude and frequency of µsPEF in relation to cardiomyocytes.

In this study, we focused on longer, monoplar pulses to explore the pathways beyond electroporation. We analyzed the effects of different µsPEF on cardiomyocytes in vitro and in vivo to identify effective parameters and to explore its mechanisms by transcriptome study, observation of mitochondria under scanning electron microscope, and experiments on mice. The findings revealed that a microsecond pulsed electric field of 1500 V/cm, 100 µs, and 50 pulses promotes effective apoptosis in vitro. Notably, our study uncovered that µsPEFs induce apoptosis in cardiac myocytes by disrupting the mitochondrial membrane structure and probably activating the mitochondrial apoptosis pathway.

Materials and methods

Cell culture and electric pulse treatments

All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. The pulsed generator applied in the in vitro experiment was PFA-C01, customized by Ruidi Biotechnology Co., LTD for scientific research. This generator allowed for flexible voltage settings (0–1000 V), adjustable pulse numbers (0-1500), variable pulse widths (10–100 µs), and the option to set the frequency to 1 Hz or electrocardiogram synchronous working mode. The generator’s output was measured with probes and oscilloscope to ensure the exact voltage were delivered as intended. The µsPEFs frequency rate was 1 Hz. The standard 2 mm electroporation cuvette (Bio-Rad, item number 1652086) was used as a replacement for the ablation electrodes.

H9C2 cells (Procell) and HL-1 cells (Procell) were rat embryonic cardiomyocytes and cardiac muscle cells, respectively. Both cell lines were cultured in complete growth medium (Procell) at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. The complete growth medium for H9C2 cells consisted of DMEM (PM150210) supplemented with 10% FBS (164210-50) and 1% P/S (PB180120), while the complete growth medium for HL-1 cells comprised MEM (PM150410) containing NEAA, supplemented with 10% FBS (164210-50) and 1% P/S (PB180120). The cells were suspended by the complete growth medium at a concentration of 7 × 105 cells per 100 µL, dispensed into a 2 mm electroporation cuvette and treated with electric pulses according to the corresponding pulse conditions. The cells were then divided into three groups: one group was treated with 50 pulses of µsPEF at 500, 800, 1000, 1500 and 2000 V/cm respectively, while another group was treated with 5, 10, 15, 20, 30, 40 and 50 pulses of µsPEF at 1500 V/cm respectively. The cells treated with no electric pulses comprised the normal control (NC) group. Apart from the difference in pulse number, the treatments for the 3 groups were identical.

Cell viability assay

Subsequent to the electric pulses, 21.4 µL of the cell suspension containing 15 × 104 cells was diluted with the same complete growth medium mentioned earlier to 1.5 ml, obtaining a concentration of 1 × 104 cells per 100µL. Then the cell suspension was dispensed into the 96-well plates with 100 µL per well. Each pulse sample was inoculated in the 96-well plates separately with 3 replicates per plate. The cell viability was measured respectively at 3 h, 6 h, 12 h, 24 h, and 48 h after the electric pulses, with additional 10 µL of CCK-8 solution per well and incubation for 1–4 h. The absorbance at 450 nm was then measured using the enzyme markers.

Cell apoptosis assay

Following the respective pulse conditions, the cell suspension subjected to electric pulses was analyzed by Annexin V-FITC/ PI fluorescent double stain apoptosis detection kit (P-CA-201, Procell Life Science & Technology) at 3 h after the electric pulses. The cell suspension was collected by centrifugation at 300 g for 5 min, resuspended with 500 µL of 1 × assay buffer, and then transferred to flow tubes. Following this, the cells were stained with Annexin V-FITC and PI for 15–20 min at room temperature, being shielded from light. The level of cell apoptosis was examined through flow cytometry, and the cell apoptosis rate was analyzed and calculated by FlowJO 7.6.1 software.

EdU cell proliferation assay

The cells were collected 3 h after the pulse treatment. The µsPEF-treated cell suspension was inoculated in the 96-well plates at 100 µL per well with 3 replicates per plate. Each well was incubated with 100 µL of complete growth medium containing 50 µM of EdU for 2 h and washed 1–2 times with PBS (HK0002,Haoke Biotechnology). Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (HK2003, Haoke Biotechnology) at room temperature for 30 min, incubated with 2 mg/mL of glycine (A502065-0500,Sangon Biotech) for 5 min, washed thrice with PBS, permeabilized with 0.5% TritonX-100 (A110694-0500, Sangon Biotech) for 10 min, and washed thrice with PBS. Subsequently, each well was incubated with 100 µL of 1X Apollo® staining solution for 30 min in the dark, followed by three PBS washes. Finally, each well was stained with 100 µL of 1X Hoechst33342 (K1076,APExBIO) reaction solution for 30 min in the dark and washed thrice with PBS. The cells were observed and images were collected under a fluorescence microscope.

RNA sequencing

Corresponding to the same time point as the viability assay and PI detection, the H9C2 cells subjected to electric pulses were collected 3 h after the treatment, transferred into test tubes, and frozen in liquid nitrogen. Subsequently, we selected high-quality samples (n = 3) and sent them to Novogene, a second-generation sequencing company based in China, for RNA-seq analysis. Following the analysis of differential gene expression, we conducted Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) classifications, KEGG pathway enrichment, and Gene Ontology (GO) biological process annotations.

RT-PCR

RT-PCR was employed to validate specific findings from the RNA-seq data. Total RNA was extracted and reverse transcribed using the RevertAid First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, K1622). The 2 × SYBR Green qPCR Master Mix (APExBIO Technology LLC, K1018), the template, and the custom-designed primers (tsingke) were thawed completely and distributed evenly into RT-PCR tubes. Gene expression analysis was performed by RT-PCR and relative gene expression was quantified. Detailed information about the specific genes the primers targeted and the source of the primers is shown in Supplementary Table 2.

Western blotting

The cells were collected 3 h after the pulse treatment. The µsPEF-treated cells were prepared by RIPA (P0013,Beyotime) and PMSF (A2587,APExBIO) lysis and then centrifuged at 12,000 g to separate the soluble components. Protein concentration was determined using a BCA protein detection kit (C503051-0500, Sangon Biotech). The sample and electrophoresis solution (ACE Biotechnology) were added for electrophoresis. The membranes were sealed with 5% skimmed milk (BS102,biosharp) or 5% BSA (A8020,Solarbio) dissolved in TBST (Sodium Chloride: Sangon Biotech. Tris-HCL: Solarbio. TWEEN-20:Hushi) at room temperature for 1 h, incubated overnight with the diluted primary antibody (Proteintech) at 4 °C, and washed thrice with TBST. The secondary antibody (Proteintech) was diluted, incubated for 30 min at room temperature, and washed thrice with TBST. After removing excess liquid, the membrane was wrapped and placed in the dark box for exposure. Subsequently, the film was developed and fixed with the development and fixing reagents. Detailed antibody information is shown in Supplementary Table 1.

Transmission electron microscope (TEM)

The cells were collected 3 h after the pulse treatment. The µsPEF-treated H9C2 cells were centrifuged and fixed with electron microscopy fixative (HK2012,Haoke Biotechnology) for 2–4 h at 4 °C. Next the samples were centrifuged, washed 3 times with PBS, pre-embedded with agarose and post-fixed with 1% osmium tetroxide. The samples were then dehydrated in ethanol and subsequently embedded overnight in a mixture of acetone and Epon 812 embedding resin. Sixty- to eighty-nanometre-thick tissue sections were cut with the help of an ultra-microtome (Leica: Leica UC7). After the sample section staining with uranium acetate and lead citrate, the mitochondrial morphology was detected under a transmission electron microscope (HITACHI: HT7800).

µsPEF ablation of the heart in mice

The PFA-C01 pulsed generator used in the in vivo experiment was identical to the one used in the in vitro experiment. The ablation electrodes applied in the in vivo experiment were customized to fit into attached ablation of mouse myocardium. The electrode tip adopted a enameled wire with 0.5 mm of diameter and pure copper core. The enameled wire was stripped of 3 mm of insulation, exposing only the copper core as the ablation electrode. The middle connecting wire was a 20Kv-dc high-voltage resistant wire. The tail end was connected to the output end of the pulse ablation device through a banana plug. The frequency of the µsPEF pulses was 1 Hz. The parameter of 1500 V/cm corresponded to an actual voltage of 300 V, with a 2 mm distance between the electrodes.

All procedures involving mice and experimental protocols were approved by Institutionl Animal Care and Use Committee of Zhejiang Chinese Medical University (Approval No. ZJCLA-IACUC-20050027) and Zhejiang Laboratory Animal Center. Mice were anesthetized using isoflurane inhalation. Euthanasia was performed by overdose of isoflurane followed by cervical dislocation to ensure minimal suffering. 60 C57 mice were purchased from Zhejiang Experimental Animal Centre, all of which were male and 8 weeks old to eliminate the possible influence of sex and age on the results of the study. The mice were initially anesthetized first, ensuring the mice were unresponsive to toe squeezing, and then their limbs were fixed on the operating board in the supine position. The skin was shaved and disinfected with alcohol. Subsequently, a median sternotomy incision was performed, the pericardium was opened and the ablation electrodes were placed on the surface of the left ventricle. Then the mice were divided into 2 groups. One group, consisting of 54 mice, received 50 pulses of µsPEF at 1500 V/cm and 100 µs on the heart. At each time point (6 h, 12 h, 24 h, 48 h, 72 h, 7d, and 14d after the ablation), 6 C57 mice were selected for pathology observation, with an additional 12 C57 mice kept as spares. The other group, consisting of 6 C57 mice, received no pulses, and served as the normal control (NC) group. Apart from the difference in pulse number, the treatments for the 2 groups were identical. The sternum and skin were closed sequentially, and the mice were placed in an incubator at 30℃ before retaining to their cages. Survival status of the mice was recorded daily. We adhered to the ARRIVE1 checklist when preparing this report.

Pathology (HE, Masson, TUNEL and immunofluorescence )

HE staining: The slices were stained with Hematoxylin for 5 min, divided with aqueous hydrochloric acid solution for 2 s, returned to blue with aqueous ammonia solution for 15–30 s, and then washed in water. Subsequently, the slices were dehydrated in 95% alcohol and stained in eosin staining solution for 5–8 s. The slices were placed consecutively in anhydrous ethanol I for 30 s, anhydrous ethanol II for 2.5 min, anhydrous ethanol III for 2.5 min, dimethyl I for 2.5 min, xylene II for 2.5 min for transparency, and finally sealed with neutral gum. The cells were observed and images were collected under the microscope.

Masson staining: The slices were stained with Weigert’s iron hematoxylin for 5 min, washed with tap water, divided with 1% hydrochloric acid alcohol, and rinsed with running tap water to return to blue. Then, the slices were stained with Lichon red acidic magenta solution for 5–10 min, quickly rinsed with distilled water, and treated with aqueous phosphomolybdic acid for 3–5 min. Following this, the slices were directly re-stained with aniline blue for 5 min, followed by a 1% glacial acetic acid treatment for 1 min, and sealed through dehydration. The cells were observed and images were collected under the microscope.

TUNEL: Following antigen retrieval, the TUNEL working solution was applied to the slices. The slices were put flat into the wet box, incubated at 37℃ for 1.5 h, and washed thrice with PBS. Subsequently, the slices were stained with DAPI for 10 min and washed thrice with PBS. Then, the slices were sealed with anti-fluorescence quenching agent. The cells were observed and images were collected under a fluorescence microscope.

Immunofluorescence staining: The slices were subjected to antigen retrieval by being placed in a repair cassette filled with EDTA antigen repair buffer in a microwave oven and washed with PBS thrice after naturally cooling. The slices were then incubated with 50–100 µL of endogenous peroxidase for 25 min at room temperature, protected from light, and washed thrice with PBS. Next, the slices were sealed with 3% BSA for 30 min at room temperature, incubated overnight with primary antibody at 4 °C in a wet box, and washed thrice with PBS. Following this, the slices were incubated with fluorescent secondary antibodies for 50 min, stained with DAPI at room temperature (protected from light), and treated with spontaneous fluorescent quencher for 5 min. After a final 3-time wash with PBS, the sections were sealed with anti-fluorescence quenching agent. The cells were observed and images were collected under a fluorescence microscope.

Statistical analysis

All data underwent statistical analysis using GraphPad Prism 8.0. to minimize operational variability. All samples were assayed concurrently on the same plate at least three times with the average concentrations calculated. The results are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Comparison was achieved using a two-tailed Student’s t-test. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

The application of ΜsPEF treatment leads to a significant reduction in cardiomyocyte activity

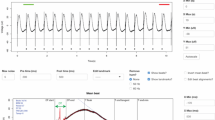

To evaluate the impact of microsecond electric pulses (µsPEFs) on the range of cardiomyocyte activity, we employed CCK8 to investigate the influence of different voltage levels and pulse quantities on cardiomyocyte activity. Additionally, we conducted a flow apoptosis analysis on cardiomyocytes to further confirm the effect of µsPEFs on cardiomyocyte apoptosis. The activity and apoptosis of cardiomyocytes appeared to be associated with voltage, pulse count, and duration of the pulsed electric field (Fig. 1, Supplementary Fig. 1). Under fixed 50 pulses at 1500 V/cm, the relative cell activity decreased to below 0.2 (p < 0.01) when the µsPEFs lasted for 30 µs or longer (Supplementary Fig. 1A). The cell mortality rate reached 87.77% at 50 µs, whereas the results of cell ablation were inconsistent. At 100 µs, the proportion of died cells increased to 91.26%, concomitant with successful and stable ablation of cardiomyocytes in vitro (Supplementary Fig. 1B). Therefore, we treated the cardiomyocytes with µsPEF at a fixed width of 100 µs for further study.

Effect of different µsPEF treatments on cell activity, apoptosis and proliferative activity of H9C2 cells. The relative cell activity and the proportion of apoptotic cells were detected by (A, B) CCK8 assay and (C, D) Annexin V/7-PI detection, respectively. The relative cell activity of H9C2 cells 3 h, 6 h, 12 h, 24 h and 48 h after the ablation (A) with increasing voltage (0–2000 V/cm) at 50 pulses and (B) with increasing pulse number (0–50) at 1500 V/cm (n = 3). The proportion of apoptotic H9C2 cells (C) with increasing voltage (0–2000 V/cm) at 50 pulses and (D) with increasing pulse number (0–50) at 1500 V/cm. (E) Representative immunofluorescence images of H9C2 cells in the NC, EP10 and EP50 groups stained with EDU (green) and DAPI (blue). EDU incorporation indicates actively proliferating cells. Data are shown as mean ± SD. *P < 0.05. **P < 0.01. Abbreviations: NC, normal control (no pulses); EP10, 10 electric pulses at 1500 V/cm; EP50, 50 electric pulses at 1500 V/cm. Each point shown in the line charts indicates an individual data point.

The results of celll viability assay unveiled a noticeable relationship between voltage, pulse number and cell viability. In experiments with a fixed 50 pulse number, the cardiomyocyte activity was hardly influenced when pulses at 500 V/cm were applied. At 800 V/cm, the relative cell activity decreased to 0.53 (p < 0.05) 3 h after the ablation, albeit with slow recovery to 0.80 (p < 0.01) 48 h after the ablation. At 1000 V/cm, the relative cell activity dropped to 0.36 (p < 0.01) and generally remained at this level over the subsequent hours. When the voltage reached 1500 V/cm, a continuous decline in relative cell activity from 0.32 to 0.14 (p < 0.01) over the following 48 h could be observed (Fig. 1A). In experiments with a fixed voltage of 1500 V/cm, the relative cell activity initially dropped to 0.74 at 15 pulses, followed by a stable recovery to 0.93 (p < 0.05). The activity restoration could still be observed at 20 pulses whereas when more than 30 pulses were employed, cell viability continued to decline, with relative cell activity dropping from 0.36 at 3 h to 0.13 (p < 0.01) at 48 h (Fig. 1B).

The results obtained through Annexin V/7-PI detection underscored a compelling association between voltage levels and apoptosis, revealing a remarkable surge in the apoptosis rate from 9.87 to 90.09% with the escalation of voltage intensity from 500 V/cm to 1000 V/cm. At 1500 V/cm, the apoptosis rate surged to 96.30% and a more stable and consistent cell ablation was achieved (Fig. 1C). Moreover, higher pulse counts also correlated with increased levels of apoptosis. A rise in the apoptosis rate from 15.82% at 10 pulses to 99.13% at 50 pulses coupled with enhanced ablation stability, could be detected (Fig. 1D). In addition, the findings obtained from H9C2 cells exhibited concordance with those observed in HL-1 cells (Supplement Fig. 1C–F). To further validate these results, we conducted EdU cell proliferation assay to assess the proliferative activity of H9C2 cells from the normal control (NC) group (no pulses), EP10 (10 electric pulses at 1500 V/cm) group, and EP50 (50 electric pulses at 1500 V/cm) group. Consistent with the previous results, the number of proliferating cells in the EP10 group observed in the field exhibited a small decrease (from approximately 68 to 44), compared with the NC group, while proliferating cells in the EP50 group were invisible (Fig. 1E). These findings suggested that the cardiomyocytes suffered irreparable damage under µsPEF, especially when exposed to over 50 pulses at 1500 V/cm.

Cardiomyocytes treated with ΜsPEF show distinct gene expression patterns

To further elucidate the molecular mechanisms underlying the promotion of apoptosis by µsPEF, transcriptome analysis was conducted on H9C2 cells following µsPEF treatment. The previous findings revealed that the EP50 group effectively represented a model for cellular damage post-ablation, with a continuous decline in cellular activity and a high apoptosis rate surpassing 95%, while the EP10 group exhibited a low cell apoptosis rate of 15.82%. Therefore, H9C2 cells from the EP50, EP10, and NC groups were chosen 3 h after the ablation for RNA sequencing to explore the ablation mechanism as well as ensure a relatively good contrast. We observed distinct gene expression patterns based on pulse duration (Fig. 2A,B). Comparing gene expression in EP10 and EP50 to the NC group, EP10 showed 136 up-regulated and 54 down-regulated genes, while EP50 had 2116 up-regulated and 2733 down-regulated genes. The overlap of differently expressed genes between the EP10 and EP50 groups was minimal, with only 13 genes up-regulated and 15 genes down-regulated (Fig. 2C–F). The findings suggest that exposure to µsPEF leads to modifications in gene expression profiles, possibly associated with declining cell vitality and elevated rates of apoptosis, indicating intricate cellular responses to the stimulus.

Major effects of different µsPEF treatments on H9C2 cells at the transcriptional level. (A) The normalized expression value of H9C2 cells in the EP50, EP10 and NC groups by DESeq 2 R package. (B) Principal component analysis of H9C2 cells in the EP50, EP10 and NC groups using normalized expression value. Volcano plots depicting the differential transcriptome expression of H9C2 cells (C) between the EP10 group and the NC group, as well as (D) between the EP50 group and the NC group. Venn diagram depicting (E) the up-regulated transcriptome expression and (F) the down-regulated transcriptome expression of H9C2 cells between the EP10 and EP50 groups. Dashed lines in the volcano plots (C and D) indicate the p-value and fold change used for identifying differentially expressed genes. Abbreviations: NC, normal control (no pulses); EP10, 10 electric pulses at 1500 V/cm; EP50, 50 electric pulses at 1500 V/cm.

Pathway enrichment analysis of cardiomyocytes response to ΜsPEF

To gain more insights into the impact of µsPEF on cardiomyocytes, we performed pathway enrichment analysis on the differently expressed genes of H9C2 cells comparing the EP50 group to the NC group. KEGG pathway analysis via GSEA highlighted that µsPEF predominantly influences several key processes of cardiomyocytes, such as Cytochrome C (Cyt C) oxidase, NADH dehydrogenase (ubiquinone) 1α subcomplex, F-type ATPase, and NADH dehydrogenase (ubiquinone) 1β subcomplex (Fig. 3A), suggesting a significant impact on mitochondrial function. Further examination of the differential gene and pathway enrichment analysis identified prominent components, including ATP6, ATP8, Ndufa 1, COX1, COX2, and COX3 (Fig. 3B). The gene ontology enrichment analysis on molecular function of up-regulated genes revealed that there was a concentration in functions related to mitochondrial activity, ribosome structure and function, redox reaction, and protein linkage. Remarkably, over half of the top 20 up-regulated pathways were associated mitochondrial function (Fig. 3C). Conversely, down-regulated genes in KEGG pathway enrichment were mainly concentrated in several signaling pathways including PI3K-Akt, MAPK, TNF, and TGF-β pathways. Moreover, these down-regulated genes exhibited associations with heart disease as well as processes like cell adhesion, protein synthesis and degradation (Fig. 3D).

Pathway enrichment analysis of the transcriptome of H9C2 cells after µsPEF treatments. (A) Analysis of KEGG signaling pathway in GSEA showing the four most affected transcriptome pathway in the EP50 group. KEGG: Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes42. (B) Differential genes and enriched signaling pathways showing the clusters of substances and their transcriptome pathways most affected in the EP50 group. GO enrichment molecular function (MF) analyses depicting the significantly-enriched pathways of (C) up-regulated transcriptome expression and (D) down-regulated transcriptome expression in the EP50 group. Clustering analysis of protein function networks revealing (E) an interactive network of actin binding, nucleotide formation, RNA ligation and ribosome formation as well as (F) an interactive network of proteins related to electron transport chain and redox reaction in the EP50 group. Heat maps displaying the expression levels of (G) Cyt c pathway clustering, (H) TNF pathway clustering, (I) TGF-β pathway clustering, (J) PI3K pathway clustering and (K) cardiomyopathy pathogenesis-associated pathway clustering in the NC, EP10 and EP50 groups. Abbreviations: NC, normal control (no pulses); EP10, 10 electric pulses at 1500 V/cm; EP50, 50 electric pulses at 1500 V/cm.

Subsequent interaction network analysis of differentially expressed genes revealed that up-regulated genes in µsPEF-treated cardiomyocytes were interconnected in functions such as polymerized actin binding, the formation of nucleotides, RNA linkage, and ribosome assembly (Fig. 3E). Additionally, gene involved in electron transport chain and redox functions exhibited clustered interaction (Fig. 3F). Further investigation and validation of gene expression in these functional clusters demonstrated a notable increase in Cyt C oxidase-related activity in cardiomyocytes after µsPEF treatment (Fig. 3G). In line with the enriched bubble chart analysis, the gene expression heat map revealed that TNF, TGF-β, and PI3K-Akt pathways were inhibited significantly after 50 pulses (Fig. 3H–J). Furthermore, a distinct down-regulation was observed in cardiomyopathy-related pathways in cardiomyocytes after pulsed electric field treatment on the gene expression heat map (Fig. 3K).

µsPEF induces cardiomyocyte apoptosis via mitochondrial disruption and elevated cytochrome C levels

To validate our transcriptome experiments, we focused on the Cyt C and PI3K-Akt pathways due to prominent trends in transcriptomics. The expression level of ATP6, COX2, ND2, Ndufaf2, CYTB, Uqcrq in the EP50 group reached 23.74, 7.79, 14.53, 71.13, 24.61 and 30.92 (p < 0.01) respectively, compared to the NC group (Fig. 4A), indicating a significant increase in Cyt C-related pathway proteins. At the same time, the relative expression level of Pik3r1, Thbs1, Ccl2, II6r, Col1a1, Fgf2 in the EP50 group decreased to 0.79, 0.66, 0.25, 0.78, 0.28 and 0.31 (p < 0.05) respectively (Fig. 4B), suggesting a pronounced down-regulation in PI3K-Akt-related pathway proteins. In contrast, in the EP10 group, the increase in proteins related to the Cyt c pathway was not statistically significant (ns) and an upregulation was observed in several proteins related to the PI3K-Akt pathway, with the relative expression levels of Pik3r1, Thbs1, Ccl2, Col1a1, and Fgf2 increasing to 1.26, 1.43, 1.52, 1.26, and 1.16 (p < 0.05) separately (Fig. 4A,B). Compared to the NC group, western blot results indicated that the relative intensity values of Akt, Bcl-xl, PARP1 in the EP10 group did not vary by more than 0.02 while the EP50 group exhibited a more pronounced decrease of 0.29 for Akt, 0.12 for p-Akt, 0.18 for Bcl-2, 0.19 for Bcl-xl, 0.3 for I-κB, 0.23 for PARP1, 0.33 for PI3K-P85 and 0.27 for NF-kB. Simultaneously, the relative intensity values of Cyt c in the EP50 group reached 0.91, showing an increase of 0.2 compared to the NC group and 0.24 compared to the EP10 group (Fig. 4C). Electron microscopy revealed that the mitochondrial structures were visible in the NC group. After 10 pulses, partial mitochondria were ruptured but mitochondria with visible and normal structures could still be found in the field. However, after 50 pulses, almost no normal mitochondria could be observed, with the cristae structure of the mitochondria disordered, fractured or disappeared. (Fig. 4D). The integrated analysis of RNA-seq, protein expression data and TEM observation suggests that µsPEF leads to cell death by inflicting irreparable injury to mitochondria and increasing Cyt c levels within the cardiomyocytes.

µsPEF causes apoptosis in cardiomyocytes by disrupting mitochondria and elevating Cyt c levels. (A,B) Fluorescence quantitative results of RT-PCR 3 h after the ablation (n = 3). (A) Relative mRNA expression levels of Cytochrome c oxidation-related pathway in H9C2 cells from NC, EP10 and EP50 groups. (B) Relative mRNA expression levels of PI3K-Akt-related pathway in H9C2 cells from NC, EP10 and EP50 groups. (C) The protein expression of Akt, p-Akt, Bcl-2, Bcl-xl, I-κB, PARP1, PI3K-P85, NF-kB and Cyt was evaluated by western blot in H9C2 cells from NC, EP10, EP20 and EP50 groups 3 h after the ablation. The numbers under the bands indicate relative intensity value. In the EP50 group, the expression of Cyt c increased, while the expression of the other proteins decreased after µsPEF compared to the NC, EP10, and EP20 groups. (D) TEM images of mitochondrial morphology in H9C2 cells from the NC, EP10 and EP50 groups. Yellow arrow: undamaged mitochondria; Red arrow: damaged mitochondria; Blue arrow: nucleus; Scale bar: 0.5 μm and 0.2 μm, respectively. Data are shown as mean ± SD. ns indicates no statistical significance. *P < 0.05. **P < 0.01. Abbreviations: TEM, Transmission electron microscope; NC, normal control (no pulses); EP10, 10 electric pulses at 1500 V/cm; EP20, 20 electric pulses at 1500 V/cm; EP50, 50 electric pulses at 1500 V/cm. Each point shown in the bar charts indicates an individual data point.

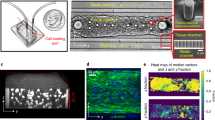

µsPEF results in cardiovascular tissue ablation by inducing the diffusion of Cyt C

To further substantiate these observations, we conducted in vivo investigations on mouse myocardium ablation using µsPEFs. Histological and Masson staining revealed dynamic changes in the mouse myocardium following electric field treatment. From 6 to 12 h post-ablation, there was a widening gap between myocardial cells in the ablation zone, accompanied by a progressively clearer ablation boundary (Fig. 5A). By 24 h, myocardial cells in the ablation zone underwent fragmentation, with an increase in red blood cell presence. At 48 h, further disintegration of myocardial cells occurred, red blood cells dissipated, and a significant infiltration of inflammatory cells was observed (Fig. 5A). By 72 h post-ablation, myocardial cell fragmentation intensified, and the number of inflammatory cells decreased (Fig. 5A). From 7 to 14 days following the ablation, progressive myocardial cell necrosis became evident, and the remaining myocardial cell fibers were nearly invisible on the 14th day (Fig. 5A).

Possible mechanisms of µsPFE-induced cardiomyocyte ablation. (A) Representative H&E and Masson staining images of C57 mouse cardiomyocyte Sect. 6 h, 12 h, 24 h, 48 h, 72 h, 7 d and 14 d after exposure to 50 pulses at 1500 V/cm, compared with the NC group. Magnification, 10× and 40×. Scale bar: 100 μm and 20 μm, respectively. (B) Representative images of C57 mice cardiomyocyte sections labeled with TUNEL (magenta) and DAPI (cyan) 6 h, 12 h, 24 h, 48 h, 72 h after 50 pulses at 1500 V/cm, compared with the NC group. Magnification, 40×. Scale bar: 20 μm. (C) Representative immunofluorescence images of C57 mice cardiomyocyte sections labeled with NF-kB (magenta) and DAPI (cyan) 24 h and 72 h after 50 pulses at 1500 V/cm, compared with the NC group. Magnification, 40×. Scale bar: 20 μm. (D) Representative immunofluorescence images of C57 mice cardiomyocyte sections labeled with Cyt c (orange-red) and DAPI (cyan) 24 h and 72 h after 50 pulses at 1500 V/cm, compared with the NC group. Magnification, 40×. Scale bar: 20 μm. Abbreviations: NC, normal control (no pulses).

TUNEL results revealed a gradual alteration in the number of TUNEL-positive cells over time, with early-stage apoptosis peaking at 24 h and subsequently declining, approaching completion by 72 h (Fig. 5B). For further exploration, we chose the 24-h and 72-h time points to investigate the specific effects of electrical pulses on myocardial tissue. Immunofluorescence images showed that 24 h after the ablation, NF-kB exhibited co-localization with the cell nucleus stained by DAPI, indicating significant nuclear translocation and activation. Additionally, abundant NF-kB expression was observed both in the cell nucleus and cytoplasm by 72 h, suggestive of dynamic intracellular distribution (Fig. 5C). Cyt c diffusion within the cell showed no obvious change at 24 h, but at 72 h post-ablation, it was observed throughout the nucleus and cytoplasm (Fig. 5D).

Discussion

Pulsed electric field ablation is an emerging technology with applications in various medical areas. Previous studies have shown that when used for atrial fibrillation, pulsed field ablation was non-inferior to conventional thermal ablation with respect to the primary efficacy end point of freedom22. Compared with RF energy used for pulmonary vein isolation(PVI), PEF induces significantly weaker and less durable suppression of cardiac autonomic regulations23. Previous computational results suggests that when the lethal electric field threshold is used, the maximum values of electric field in adjacent organs are much lower than the lethal electric field threshold in these organs, indicating that they are not affected by the PEF energy24. In our research, we delved deeper into exploring the fundamental mechanisms induced by µsPEF. The first part of our study was the in vitro experiment, which explored the effective range of the microsecond pulsed electric field on mouse cardiomyocytes and the more specific mechanism by which the ablation works. According to Xuying Ye et al.’s study, when the electric field intensity exceeds 1000 V/cm with 70 pulses and a pulse width of 70 µs, the injury of cardiomyocytes is sharply enhanced25. Besides, the experimental results of Sahar Avazzadeh et al. showed that IRE (irreversible electroporation) produces significant cell death at field strengths greater than 1000 V/cm, when deployed with at least 50 pulses26. Based on the reference parameters provided by these studies, we conducted further experiments to validate these results and explored more specific parameters. It turns out that the cardiomyocytes show obvious apoptosis when µsPEF reaches a certain voltage or number of pulses. Our data show that microsecond pulsed electric fields with 1500 V/cm, 50 pulses, and 100 µs reliably induced cardiomyocyte death in vitro, providing a practical framework for further investigation. Different electric pulse parameters (number, duration, and voltage-to-distance ratio) result in varying cell injuries. For instance, ns, µs, and ms pulses cause membrane damage and ATP depletion, while ns and µs pulses additionally induce mitochondrial and DNA damage21. Although temperature is a potential factor influencing the pulse treatment, our experiments were carried out at a controlled 25 °C. During the process, no significant temperature increase was detected. Then we explored the possible mechanisms of microsecond pulsed electric field ablation on myocardial tissue, demonstrating its superiority for clinical application. Previous study shows that pulsed electric field ablation acts by inducing injury of cell membranes20, thus we initially performed pathway enrichment analysis and then observed the morphology of mitochondria. Our preliminary transcriptome sequencing results indicated a significant up-regulation trend in mitochondria-related transcription levels and the observation of TEM showed damaged mitochondrial structure. The results correspond to the study by Justina Kavaliauskaitė et al.27 which shows that within a certain range, cell membrane integrity and viability decreased with increasing electric field strength. Zhang et al.’s study also shows that pulsed electric fields affects the permeability of the cell membrane and can affect the interior of the cell28. Therefore, we determined that electrical ablation might have induced rupture of mitochondrial membrane, overflow of mitochondrial contents, and massive up-regulation of mitochondrial-related protein to compensate for mitochondrial function. What’s more, it has been indicated that up-regulating cytochrome c expression is associated with apoptosis29 and cytochrome c stored in mitochondria is released during apoptosis30,31. Based on these previous studies and our WB results, we speculated that the observed elevation in cytochrome c levels may be associated with mitochondrial damage and apoptosis. Meanwhile, Ishan Goswami et al.32 find that mitochondrial function is impaired during the ablation process. Therefore, we can roughly judge that the microsecond pulse electric field ablation causes cell damage by activating the mitochondrial apoptosis pathway. This is consistent with Xinhua Chen’s findings in liver cancer, which shows that µsPEF inhibits the growth of HCC in nude mice by causing mitochondrial damage, tumor necrosis and non-specific inflammation33. The last part of our study was the in vivo experiment on mice, providing strong evidence for the results of the in vitro experiments. Copper electrodes are not commonly used due to copper being a heavy metal with poor biocompatibility. We found that 24 h and 72 h were the critical points for myocardium in the ablation zone to undergo fragmentation and necrotic resorption respectively, thus we investigated the changes of NF-κB and Cyt c in the intracellular cite at the two points of time. The results suggest that the stimulation of µsPEF first induced inflammatory responses, characterized by the translocation of NF-κB into the nucleus for regulation and a large number of infiltrated inflammatory cells. The decrease in NF-kB in the in vitro setting could signify a rapid cellular response to extracellular conditions, while the increase observed at 24 and 72 h in the in vivo experiment may reflect the gradual recovery and regulatory processes within the in vivo environment. This could indicate a positive regulatory mechanism facilitating cell survival and repair processes. However, as Cyt c accumulates in the cell for a long time, it disrupts the normal functioning of myocardial cells within the ablation zone, ultimately triggering the initiation of a necrotic apoptotic program. Mitochondrial involvement was confirmed by loss of membrane potential, cytochrome c release, caspase-9 activation, and shifts in apoptotic regulators: upregulation of BAX/BAK/BAD and downregulation of Bcl-2/Bcl-xL/Mcl-1, indicating intrinsic apoptosis pathway activation21. In previous study, transmission electron microscopy revealed clustered and swollen mitochondria with misaligned cristae, accompanied by nuclear degeneration and chromatin condensation34. Several studies have shown that pulsed electric field-induced cell ablation is associated with altered calcium ion concentrations35,36, and calcium ions are strongly correlated with the oxidative phosphorylation function of mitochondria37. We did not detect changes in the calcium-associated pathway perhaps because the change in calcium ion was a more transient change and the specimens we sampled were cells several hours after µsPEF treatment, by which time the calcium-associated changes might have returned to normal. Furthermore, several studies have shown that µsPEF leads to increased intracellular levels of reactive oxygen species38 and ATP depletion39. Although not directly involved in our study, our cellular transcriptome results show that mitochondria-associated transcriptomes are more active in cells after electric pulses, which may be a compensation to restore mitochondrial function. Additionally, our experiments show that the dispersal of mitochondrial contents into the cytoplasm after ablation may lead to increased levels of intracellular oxidative stress, resulting in a progressive depletion of intracellular ATP. Our study demonstrates the extremely likely role of µsPEFs in myocardial ablation under suitable conditions and provides strong evidence for the clinical promotion of pulsed electric field in the treatment of atrial fibrillation at the mechanism level. Besides, our study provides a more precise parameter of µsPEF that can be used as a reference for others conducting µsPEF studies. We will follow up with further target and mechanism exploration. In addition, we will continue to explore the existence of stable models of atrial fibrillation and follow up with pulsed electric field ablation on disease models.

Limitations of the study

As the study primarily explored the effect of µsPFF on normal myocardium, it may have only limited reference for the effect of ablation of diseased myocardium. Some scholarly studies have found that pulsed electric fields are more inclined to act on active cells40, while some oncology-related studies have shown that µsPEFs preferentially act on tumor cells with irregular morphology, suggesting that they may have some selectivity for abnormal cells41.

Data availability

Data related to the RNA-seq have been uploaded to the GEO database (GEO Submission (GSE214387)) and will be available when the article is published.

References

Lippi, G., Sanchis-Gomar, F. & Cervellin, G. Global epidemiology of atrial fibrillation: an increasing epidemic and public health challenge. Int. J. Stroke 16, 217–221. https://doi.org/10.1177/1747493019897870 (2021).

Chung, M. K. et al. Atrial fibrillation: JACC Council perspectives. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 75, 1689–1713. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2020.02.025 (2020).

Kornej, J., Börschel, C. S., Benjamin, E. J. & Schnabel, R. B. Epidemiology of atrial fibrillation in the 21st century: Novel methods and new insights. Circ. Res. 127, 4–20. https://doi.org/10.1161/circresaha.120.316340 (2020).

Escudero-Martínez, I., Morales-Caba, L. & Segura, T. Atrial fibrillation and stroke: A review and new insights. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 33, 23–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tcm.2021.12.001 (2023).

January, C. et al. 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: A report of the American college of cardiology/american heart association task force on practice guidelines and the heart rhythm society. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 64, e1–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2014.03.022 (2014).

Reddy, Y. N. V., Borlaug, B. A. & Gersh, B. J. Management of atrial fibrillation across the spectrum of heart failure with preserved and reduced ejection fraction. Circulation 146, 339–357. https://doi.org/10.1161/circulationaha.122.057444 (2022).

Brundel, B. et al. Atrial fibrillation. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 8, 21. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41572-022-00347-9 (2022).

Verma, A. et al. Pulsed field ablation for the treatment of atrial fibrillation: PULSED AF pivotal trial. Circulation 147, 1422–1432. https://doi.org/10.1161/circulationaha.123.063988 (2023).

Valipour, A. et al. Bronchial rheoplasty for treatment of chronic bronchitis. Twelve-Month results from a multicenter clinical trial. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 202, 681–689. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201908-1546OC (2020).

Miao, X., Yin, S., Shao, Z., Zhang, Y. & Chen, X. Nanosecond pulsed electric field inhibits proliferation and induces apoptosis in human osteosarcoma. J. Orthop. Surg, Res. 10, 104. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13018-015-0247-z (2015).

Kidd, V. D., Strum, S. R., Strum, D. S. & Shah, J. Genicular nerve radiofrequency ablation for painful knee arthritis: the why and the how. JBJS Essent. Surg. Techniques. 9, e10. https://doi.org/10.2106/JBJS.ST.18.00016 (2019).

Qian, J. et al. Blocking exposed PD-L1 elicited by nanosecond pulsed electric field reverses dysfunction of CD8 T cells in liver cancer. Cancer Lett. 495, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.canlet.2020.09.015 (2020).

Zhao, J. et al. Antitumor effect and immune response of nanosecond pulsed electric fields in pancreatic cancer. Front. Oncol. 10, 621092. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2020.621092 (2020).

Liu, H., Zhao, Y., Yao, C., Schmelz, E. M. & Davalos, R. V. Differential effects of nanosecond pulsed electric fields on cells representing progressive ovarian cancer. Bioelectrochem. (Amsterdam Netherlands) 142, 107942. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bioelechem.2021.107942 (2021).

Verma, A., Asivatham, S. J., Deneke, T., Castellvi, Q. & Neal, R. E. 2nd. Primer on pulsed electrical field ablation: Understanding the benefits and limitations. Circ.: Arrhythmia Electrophysiol. 14, e010086. https://doi.org/10.1161/circep.121.010086 (2021).

Reddy, V. Y. et al. Pulsed field ablation for pulmonary vein isolation in atrial fibrillation. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 74, 315–326. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2019.04.021 (2019).

de Caro, A., Talmont, F., Rols, M. P., Golzio, M. & Kolosnjaj-Tabi, J. Therapeutic perspectives of high pulse repetition rate electroporation. Bioelectrochemistry 156, 108629. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bioelechem.2023.108629 (2024).

Koruth, J. S. et al. Pulsed field ablation versus radiofrequency ablation: esophageal injury in a novel Porcine model. Circ. Arrhythm. Electrophys. 13, e008303. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCEP.119.008303 (2020).

Stewart, M. T. et al. Intracardiac pulsed field ablation: proof of feasibility in a chronic Porcine model. Heart Rhythm 16, 754–764. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrthm.2018.10.030 (2019).

Turagam, M. K. et al. Safety and effectiveness of pulsed field ablation to treat atrial fibrillation: One-year outcomes from the MANIFEST-PF registry. Circulation 148, 35–46. https://doi.org/10.1161/circulationaha.123.064959 (2023).

Batista Napotnik, T., Polajžer, T. & Miklavčič, D. Cell death due to electroporation: A review. Bioelectrochemistry 141, 107871. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bioelechem.2021.107871 (2021).

Reddy, V. Y. et al. Pulsed field or conventional thermal ablation for paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. N. Engl. J. Med. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2307291 (2023).

Stojadinović, P. et al. Autonomic changes are more durable after radiofrequency than pulsed electric field pulmonary vein ablation. JACC Clin. Electrophysiol. 8, 895–904. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacep.2022.04.017 (2022).

González-Suárez, A. et al. Full torso and limited-domain computer models for epicardial pulsed electric field ablation. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 221, 106886. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmpb.2022.106886 (2022).

Ye, X. et al. Study on optimal parameter and target for Pulsed-Field ablation of atrial fibrillation. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 8, 690092. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcvm.2021.690092 (2021).

Avazzadeh, S. et al. Establishing irreversible electroporation electric field potential threshold in A suspension in vitro model for cardiac and neuronal cells. J. Clin. Med. 10(22), 5443. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10225443 (2021).

Kavaliauskaitė, J., Kazlauskaitė, A., Lazutka, J. R., Mozolevskis, G. & Stirkė, A. Pulsed electric fields alter expression of NF-κB Promoter-Controlled gene. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23(1), 451.. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23010451 (2021).

Zhang, Y. et al. Molecular and histological study on the effects of non-thermal irreversible electroporation on the liver. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 500, 665–670. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.04.132 (2018).

Han, B. et al. Coptisine-induced apoptosis in human colon cancer cells (HCT-116) is mediated by PI3K/Akt and mitochondrial-associated apoptotic pathway. Phytomedicine 48, 152–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phymed.2017.12.027 (2018).

Duan, Z. et al. Optical and electrochemical probes for monitoring cytochrome C in subcellular compartments during apoptosis. Angew Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 62, e202301476. https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.202301476 (2023).

Burke, P. J. & Mitochondria Bioenergetics and apoptosis in cancer. Trends Cancer 3, 857–870. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trecan.2017.10.006 (2017).

Goswami, I. et al. Influence of pulsed electric fields and mitochondria–cytoskeleton interactions on cell respiration. Biophys. J. 114, 2951–2964. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpj.2018.04.047 (2018).

Chen, X. et al. Preclinical study of locoregional therapy of hepatocellular carcinoma by bioelectric ablation with microsecond pulsed electric fields (µsPEFs). Sci. Rep. 5, 9851. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep09851 (2015).

Kawamura, I. et al. Ultrastructural insights from myocardial ablation lesions from microsecond pulsed field versus radiofrequency energy. Heart Rhythm. 21, 389–396. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrthm.2023.12.017 (2024).

Hanna, H., Denzi, A., Liberti, M., André, F. M. & Mir, L. M. Electropermeabilization of inner and outer cell membranes with microsecond pulsed electric fields: Quantitative study with calcium ions. Sci. Rep. 7, 13079. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-12960-w (2017).

Novickij, V. et al. Bioluminescent calcium mediated detection of nanosecond electroporation: grasping the differences between 100 Ns and 100 Μs pulses. Bioelectrochem. (Amsterdam Netherlands). 145, 108084. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bioelechem.2022.108084 (2022).

Agarwal, A. et al. Transient opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore induces microdomain calcium transients in astrocyte processes. Neuron 93(3), 587–605. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2016.12.034 (2017).

Tanori, M. et al. Microsecond pulsed electric fields: An effective way to selectively target and radiosensitize medulloblastoma cancer stem cells. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 109, 1495–1507. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrobp.2020.11.047 (2021).

Polajzer, T., Jarm, T. & Miklavcic, D. Analysis of damage-associated molecular pattern molecules due to electroporation of cells in vitro. Radiol. Oncol. 54, 317–328. https://doi.org/10.2478/raon-2020-0047 (2020).

Neal, R. E. et al. In vivo irreversible electroporation kidney ablation: Experimentally correlated numerical models. IEEE Trans. Bio Med. Eng. 62, 561–569. https://doi.org/10.1109/TBME.2014.2360374 (2015).

Yao, C. et al. Nanosecond pulses targeting intracellular ablation increase destruction of tumor cells with irregular morphology. Bioelectrochem. (Amsterdam Netherlands) 132, 107432. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bioelechem.2019.107432 (2020).

Kanehisa, M., Furumichi, M., Sato, Y., Matsuura, Y. & Ishiguro-Watanabe, M. KEGG: biological systems database as a model of the real world. Nucleic Acids Res. 53, D672–d677. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkae909 (2025).

Funding

This research was completed with the financial support of General Program, National Natural Science Foundation of China (Project Number: 82070516), Youth program, National Natural Science Foundation of China (Project Number: 82102183) and Youth Exploration Program, Zhejiang Province (Project Number: LQ20H160026).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Experiments were conceived by Q. Gao, S. Wu, M. Li, M. Zhang, R. Chen, X. Dai and P. Teng; The experiments were carried out by S. Wu, M. Li, Q. Gao, R. Chen, X. Dai, B. Wu, L. Hong, L. Liu, L. Ma and P. Teng. The writing, statistical analysis and formal analysis were performed by Q. Gao, M. Zhang, S. Wu and R. Chen. The manuscript was reviewed by M. Zhang, M. Li and P. Teng. All the authors read and approved the final version manuscript. All co-authors confirmed their contribution.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gao, Q., Zhang, M., Chen, R. et al. Microsecond pulsed electric fields induce myocardial ablation by secondary mitochondrial damage and cell death mechanisms. Sci Rep 15, 10132 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-94868-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-94868-4