Abstract

Airborne biological particles, such as pollen, fungi, bacteria, viruses, and plant or animal detritus, are known as bioaerosols. Understanding bioaerosols’ behavior, especially their reaction to pollutants and atmospheric conditions, is crucial for addressing environmental and health issues related to air quality. Such complex investigations can benefit from experiments in controlled but realistic environments, such as the Atmospheric Simulation Chamber facility ChAMBRe (Chamber for Aerosol Modeling and Bio-aerosol Research). In this work, we report on the results of several experiments that were conducted at ChAMBRe using three strains of bacteria: E. coli, B. subtilis, and P. fluorescens. The goal of these experiments was to quantitively study how the culturability of these bacteria is affected by exposure to NO, NO2, and light. The experimental approach was simple but carefully controlled: before being introduced into ChAMBRe, the bacteria samples were characterized using three different methods to determine the ratio of viable to total bacteria. The bacteria suspension was then aerosolized and introduced into ChAMBRe, where it was exposed to two different concentrations of NO and NO2, in dark conditions and with simulated solar radiation. The culturability of the bacteria was assessed by collecting bacteria samples directly onto Petri dishes by an Andersen impactor at various time intervals after the end of injection. Finally, the formed bacteria colonies were counted after 24–48 h of incubation to measure their culturability and the temporal trend. The results show a reduction of culturability for all bacteria strains when exposed to NO2 (from 50 to 70%) and to high concentrations of NO (i.e. around 30% at more than 1200 ppb) at concentration values higher than the typical urban ambient values. Even higher effects were observed exposing the bacteria strain to a proxy of solar light. The findings show how atmospheric simulation chambers help the comprehension of interactions between pollutants and bioaerosols in controlled atmospheric environments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Air pollution presently constitutes the foremost environmental hazard to human health, whether indoors and outdoors, by chemical, physical, or biological agents that alter the natural properties of the atmosphere1. Outdoor and indoor air pollution contribute to respiratory and cardiovascular disorders, affect the central nervous system, and are significant sources of morbidity and mortality. Consequently, there is an increasing political, journalistic, and economic focus on air quality concerns, and public health threats will garner heightened attention in the forthcoming years. Mitigating air pollution and its effects necessitates a comprehensive understanding of its origins, the mechanisms of pollutant transport and transformation in the atmosphere, the temporal changes in atmospheric chemical composition, and the repercussions of pollutants on human health, ecosystems, and climate.

As a result, there is a growing interest in characterizing bioaerosols and in the factors influencing the distribution and microbial diversity, particularly due to their impact on the climate and human health. It has been suggested that up to 25% of atmospheric aerosol may be made up of materials of biological origin2. Bioaerosols consist of various components, with bacterial species being one of the most significant. According to their natural habitats, including woods, mountains, farms, and cities3, airborne bacteria have a cell count of between 104 and 108 per cubic meter4; their species diversity varies complexly, exhibiting great diversity5,6.

These bacteria mainly originate from natural sources like soil7, water, plants, and human activities such as crop cultivation, livestock operations and biomass burning activities8,9 and contribute significantly to ecological balance and atmospheric processes. As a matter of fact, studying the viability of airborne bacteria is crucial for environmental and public health reasons: in particular, the ice nucleation activity of some airborne bacteria, which are mostly phytopathogens, can induce cloud and ice formation, leading to precipitation10,11. This can have an impact on climate and the dispersion of microbial biogeography: viable bacteria contribute to nutrient cycling and may play roles in processes like carbon sequestration or nitrogen fixation when deposited on new environments12. In recent years, several studies have reported that airborne microorganisms can cause diseases in animals and humans, including respiratory and skin diseases13,14. Certain bacteria, such as Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Legionella pneumophila, can become aerosolized and lead to infections15,16. In addition, knowing how long bacteria remain viable in the air aids in understanding transmission dynamics, in risk assessment and in the formulation of disease control strategies in crowded places like hospitals, schools, and public transportation. Finally, because bioaerosol can alter the oxidative potential of the harmful compounds found in airborne PM (Particulate Matter), it can alter the toxicity of PM17,18.

The relationship between bacteria and other organic and inorganic atmospheric components determines bacterial viability19,20,21,22; this means that different environmental conditions have an impact on the survivability of bacteria. The most researched variables with abiotic or biotic effects include temperature, relative humidity (RH), wind and UV radiation exposure23. Higher temperatures and moderate RH levels often favour bacterial survival and growth. However, extremes in temperature or relative humidity that fall outside of the ideal range can lead to decreased viability and higher vulnerability to environmental stresses24. A study showed that S. aureus have significantly lower survival rate in the aerosol at RH above 60%25. Exposure to UV radiation drastically decreases the viability26. In a broader view, bacteria viability can be influenced by solar radiation; they can show different tolerances to damaging radiation and both positive and negative effects of solar radiation exposure are reported in the literature. Negative effects are both direct and indirect, especially due to the UV fraction of the radiation. UVB radiation induced cellular damages on DNA/RNA, such as the formation of photoproducts starting from the nucleic acid or strand breaks and base modifications27. UVA and visible radiation are responsible for oxidative stress by ROS (Reactive Oxygen Species) generation which lead to different DNA lesions. However, the UVA can be also responsible for the activation of photolyase, a repair enzyme involved in photoreactivation28,29. Additional investigations demonstrated a correlation between nanoparticles discharged into the environment and bacterial viability. Silver nanoparticles (AgNPs), utilized as antiseptics and medical treatments, have been shown to exhibit toxicological effects on diverse organisms, including bacteria, fungi and algae30,31,32. Environmental stressors on bacteria can also induce the viable but not culturable (VBNC) state: it refers to a state in which bacteria are alive but cannot be grown on standard laboratory culture media33. VBNC is a survival strategy for bacteria in harsh environments, such as nutrient deprivation, extreme temperatures, osmotic shock, oxidative stress and UV irradiation enabling them to withstand adverse conditions until conditions become favourable again34. VBNC bacteria elude detection by standard plate counting methods (the culturability), resulting in an underestimation of possible microbiological hazards35. The examination of bacterial viability in the atmosphere is intricate owing to the dynamic and diverse nature of aerial environments; experiments conducted in controlled conditions, such as an Atmospheric Simulation Chamber (ASC), can facilitate the investigation of these factors’ effects on bacterial viability. ASC provides a controlled environment for researchers to mimic atmospheric conditions and study airborne bacteria behaviour, survival, and interactions in a laboratory setting The ASCs are used to examine the effect of bioaerosol on ice nuclei activity36. In light of the public health concerns linked to bioaerosol contamination and the numerous uncertainties regarding the survival and transformation of bioaerosols, including bacteria, in the atmospheric environment, recent innovative chamber studies have commenced to tackle these challenges37,20. Specifically, our facility ChAMBRe (Chamber for Aerosol Modelling and Bio-aerosol Research)38, provides a consistent and expedited methodology that bridges in vivo and in vitro studies for the examination of biological systems. Our experimental modelling employs living organisms to replicate biological processes under controlled conditions.

Here, we present the results of a set of experiments which investigated the effects of different concentrations of NO and NO2, in dark conditions and of simulated solar radiation, on the survival of three bacterial strains: E. coli, B. subtilis and P. fluorescens. These two gases were selected as they are products of combustion processes, predominantly generated by transportation, energy generation, household heating and cooking, and manufacturing facilities; their concentration serves as a significant indicator of anthropogenic activity. NO2 significantly contributes to smog and fine particulate matter generation, acting as a catalyst for tropospheric ozone and as a precursor for secondary inorganic aerosols, and is associated with respiratory and cardiovascular disorders39. The study aims to offer insights how an ASC can be an instrument to study the bacteria viability and how high concentrations of NO and NO2 and light affect the bacteria culturability.

Material and method

Bacteria strains and techniques of inoculum characterization

Three bacteria strains, Escherichia coli, Bacillus subtilis, and Pseudomonas fluorescens, widely used in biotechnology and research, have been selected. These prokaryotic cells were chosen because they are easy to propagate and study in the laboratory and they are model organisms used to study biological systems40. In addition, they can also be found in the air due to soil resuspension or human activities41,42,43. The details of the bacteria strains used are reported in Supplementary Material (S2).

To prepare the bacteria suspension for the chamber experiments, each bacteria strain was grown in 30 mL of broth; specifically, tryptic soy broth (TSB) was used for E. coli and B. subtilis, while P. fluorescens required nutrient broth (NB). Bacteria culture is incubated into a shaker incubator (SKI 4 ARGOLAB, Carpi, Modena, Italy) for the time needed to reach the desired OD, usually between 1 and 2 h. The shaking speed is 200 rpm while the temperature depends on the bacteria strain (37 °C for E. coli and B. subtilis and 25 °C for P. fluorescens). The growth was continuously monitored by measuring the absorbance at l = 600 nm (OD600nm) with a spectrophotometer (Shimazu 1900) until it reached the logarithmic (log) phase (around 0.5–0.6).

At this point, 20 mL of the bacteria suspension were centrifugated (B. subtilis and E. coli at 3000 rpm for 10 min; P. fluorescens at 5000 rpm for 10 min) and resuspended in 20 mL of sterile physiological solution (NaCl 0.9%).

The purpose of preparing the bacteria suspension is to ensure the maximum number of viable bacteria and to determine the ratio of viable to total bacteria before injection into the chamber. Three different methods were used to collect these data: the first one was to count the Colony Forming Unit (CFU) on agar plates. Four Petri plates were prepared with two different dilution levels (two plates for each dilution level). The number of CFUs was then averaged to determine the bacterial concentration in the solution, along with its statistical uncertainty (standard error of weighted mean). The dilution levels for plating were 10− 5 and 10− 5.5 for E. coli and B. subtilis, and 10− 5.5 and 10− 6 for P. fluorescens. This technique required at least 24 h of incubation (37 °C for E. coli and B. subtilis and 25 °C for P. fluorescens) before CFU counting became possible, and the results were known the day after the injection into the chamber. The second method involved an automatic cell counter, the QUANTOM Tx™ (QTx) from Logos Biosystems (https://logosbio.com/quantom-tx/). The QTx is a computerized cell counter that uses images to detect and quantify individual bacterial cells. The system automatically captures and analyzes several photos of fluorescence-stained cells to detect bacterial cells. Using two different stains, SYTO 9 and Calcein AM (CAM), the QTx can count total and viable cells, respectively. For each count, we perform replicates measuring two slides for each sample. The primary constraint of QTx is the viable dye: the CAM can be used to detect live cells, but its capability for Gram-negative bacteria is limited44,45,46,47.

To address the limitations of the two previous techniques, a fluorescence microscopy approach was also pursued. The technique allowed us to choose the proper dyes and count the viable and total bacteria with high accuracy before the start of injection. The kit used for the experiments was the LIVE/DEAD BacLight Bacterial Viability Kits (Molecular probes by Thermo Fisher Scientific Waltham, Massachusetts, USA)48. The kit contains SYTO 9 dye (for the total cells) at a concentration of 3.34 mM (Component A) in 300 µL of DMSO solution, and Propidium iodide (PI) (for the dead cells) at a concentration of 20 mM (Component B) in 300 µL of DMSO solution. Finally, the live cells can be retrieved by the ratio between dead and total cells.

To perform the LIVE/DEAD test, the bacteria solution was diluted by a factor of 10 to prepare the sample and then stained with a mixture of Components A and B in a 1:1 ratio. After staining, the sample was incubated at room temperature for 10–15 min and protected against light. After the incubation period, a 10 µl sample was placed in a Thoma counting chamber, and the concentration of viable and total bacteria was determined using an optical fluorescence microscope (BX43F EVIDENT Europe GmbH, Hamburg, Germany). The images captured by the microscope were analyzed using Fiji ImageJ software 2.9 (Wayne Rasband, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA). The complete procedure carries out about 20 min, obtaining information about the injection solution (viable to total ratio) before injecting the bacteria into the atmospheric simulation chamber.

Bacteria injection in ChAMBRe and experiments setup

Experiments were performed in the ChAMBRe ASC: it is an indoor stainless-steel chamber, with a volume of about 2.2 m3. The chamber equipment is described in38,49,50,51. The whole experimental procedure is described in51, with proper tuning for each different bacteria strain. Here, we briefly summarize the procedure.

The bacteria in the physiological solution were introduced into the chamber volume using the Sparging Liquid Aerosol Generator (SLAG, CH Technologies) with a 0.75′′ diameter porous disc and nominal pore size of 2 μm52, which improved the consistency of results in previous experiments44. 2 mL of the bacterial suspension with a syringe pump flowrate of 0.4 ml min− 1 were dripped onto the SLAG porous stainless-steel disk and nebulized inside ChAMBRe.

After the injection, bacteria total concentration was monitored continuously by WIBS-NEO (Droplet Measurement Technologies®) and bacteria culturable concentration was determined by collecting bacteria directly in Petri dishes using an Andersen impactor (Single Stage Andersen Cascade Impactor, TISCH Environmental working at a fixed air flow of 28.3 lpm) at various time intervals. The initial time of the experiment (t = 0) is three minutes after the end of injection: this time window was selected as it is the necessary time for the injected liquid solution to mix and achieve homogeneity inside the ChAMBRe’s volume; as reported in38, the mixing time of ChAMBRe is about 2 min, keeping the mixing fan on at a constant rotation speed of 5 Hz (selected for our experiments). The data produced by WIBS were examined offline using an internally built software tool, as detailed in51. The program enabled us to reduce data and isolate the bacterial signal by analyzing the scatterplot (intensity fluorescence against particle size) and choosing the region of interest (ROI) pertaining to bacteria. The scatterplots and ROIs of all bacteria are reported in the figure S1 of Supplement. Furthermore, the Andersen impactor has 400 orifices and deposits the aerosol in specific patterns on the plate. To minimize the likelihood of multiple bacteria landing on the same locationthe bacterial concentration in the chamber and sampling duration were set to achieve a maximum of 200 colonies on each petri dish. Additionally, during the initial sampling, which exhibited elevated bacterial concentrations in ChAMBRe, three Petri dishes were sampled in succession, and the CFU was averaged; the coefficient of variance for the CFUs obtained from the three Petri dishes was less than 20% for all experiments. The sampling times for all experiments are documented in the table S1 of Supplement. Each Petri dish, collected by Andersen impactor, was incubated at 37 °C for 24 h for E. coli and B. subtilis and 25 °C for 48 h for P. fluorescens.

The correlation between bacteria culturability and air quality can be studied by examining the impact of atmospheric conditions on bacteria culturability compared to “baseline experiments” (i.e. without any pollutant inside ChAMBRe, see Section “Baseline experiments”). The conditions of baseline experiments, chosen, were approximately 21 °C ambient temperature, ambient pressure, about 400 ppm of CO2 (ambient concentration), about 60% relative humidity (RH) and dark conditions. These conditions were selected because bacteria generally thrive in moderate temperatures; most pathogenic bacteria prefer temperatures between 20 °C and 40 °C53. Extremely high or low temperatures can inhibit bacterial growth or kill bacteria. Secondly, bacteria tend to survive longer in environments with higher relative humidity (at or above 60%)54. Finally, ultraviolet (UV) light from the sun is detrimental to bacterial survival. Bacteria are more viable in indoor environments or shaded areas where they are less exposed to UV radiation55.

For each bacterial strain, we conducted several experiments by varying the concentration of NO and NO2 (900 and 1200 ppb) in ChAMBRe and comparing the results with those obtained under baseline conditions. These gas concentration values have been selected to expose the bacterial strain to arbitrary pollutant concentration values about 9–12 times higher than the maximum hourly ambient limits (200 µg m− 3 NO2 ppb, P9_TA(2024)0319, European Parliament legislative resolution of 24 April 2024). This choice aims to favour the interactions between bacteria, gaseous species and light, making them observable within the experimental timeframe to maintain viable bacteria suspended in ChAMBRe. The gas concentration inside the chamber was kept constant by a control system based on a real-time NOx gas monitor (ENVEA-AC32e) as described in51.

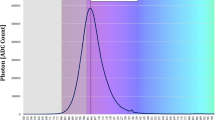

We also performed experiments in light conditions, using a custom solar simulator manufactured by Sciencetech Inc.™ and installed on the top of the upper dome of the chamber. Using a special filter (AM1.5G 3 × 3” air mass filter; Sciencetech Inc.™) simulating the optical absorption of the atmosphere, the irradiance spectrum inside the chamber is similar to the Sun irradiance spectrum measured at geographic coordinates (44.403°N 8.972°E, 40 m a.s.l.) nearby European latitudes51. The irradiance spectrum of solar simulator and Sun at our geographic coordinates is reported in figure S2 of supplement.

At the end of each experiment, the chamber volume is pumped down to 10− 2 mbar by a vacuum pump system including a TRIVAC® D65B rotary pump and a RUVAC WAU 251 root pump. Then, ChAMBRe is refilled with ambient air filtered by a multi-stage filtration system. This cleaning procedure ensures that there is no contamination during experiments; we periodically check the level of cleanling given by the procedure performing Andersen sampling in the absence of bacteria. If needed, an UV lamp (W = 60 W; l = 253,7 nm; UV-STYLO-F-60 H, Light Progress s.r.l.) can be used for an higher sterilization level.

Results and discussion

Characterization of injection liquid

The average results of inoculum characterization for each experiment, conducted using the three techniques described earlier, are depicted in Fig. 1.

Average and standard deviation of the ratio of VF/TF (viable and total cells measured by fluorescence microscopy), CFU/VF (CFU and viable cells measured by fluorescence microscopy), TF/TQ (total cells measured by fluorescence microscopy and QTx, respectively) and VQ/TQ (viable and total cells measured by QTx) of all bacteria strains.

For all experiments, the average ratio of viable to total cells, determined using live and dead dyes and fluorescence microscopy (VF/TF), was found to be over 90% for all bacterial strains. This confirmed that during the log phase, the bacteria are predominantly alive. The average ratio of CFU to viable cells (CFU/VF), as measured by fluorescence microscopy, was about 80%. This suggested that approximately 20% of viable cells were viable but non-culturable (VBNC) cells, which means they are live bacteria that do not grow or divide56. When using fluorescence microscopy and QTx (TQ) to measure total cell counts, there was a partial agreement for B. subtilis, with an average ratio and standard deviation of (72 ± 14) %. However, for E. coli and P. fluorescens, the QTx overestimated the bacteria by a factor of about 5 and 2, respectively. These two Gram-negative bacteria are smaller than B. subtilis, and the QTx’s cell detection and de-clustering algorithms were not able to separate the bacteria from, for example, dye fragments. Finally, the ratio of viable to total cells, measured with QTx, was compatible with the value obtained with the Thoma chamber for B. subtilis, the only Gram-positive bacteria in our experiments. It was not possible to show the VQ/TQ ratio for Gram-negative bacteria because the viable dye used by QTx is not suitable for this type of bacteria, as mentioned above.

Baseline experiments

For each bacteria strain from separate cultures, several baseline experiments were conducted: the results in terms of total concentration (cells m− 3), measured by WIBS, and culturable concentration (CFU m− 3), obtained by counting the CFU on Petri dishes, collected by Andersen impactor, for B. subtilis, P. fluorescens and E. coli are reported in Figs. 2, 3 and 4.

The values of total cells at t = 0 of all bacteria strains are compatible within the uncertainties: the average and standard deviation of cells concentration is (4.4 ± 1.0)·105 m− 3 and (4.2 ± 1.3)·105 m− 3 for B. subtilis and P. fluorescens respectively (in agreement with (3.4 ± 0.7)·105 m− 3 for E. coli reported in51). That means that the injection procedure of bacteria inside the chamber is robust and well repeatable. The cuturable cells (CFU m− 3) at t = 0 of all bacteria are significantly lower than the corresponding total cells: the average and standard deviation of CFU cm− 3 of P. fluorescens is compatible, within the uncertainties, with the value of E. coli reported in51 ((3 ± 1)·104 m− 3 and (4 ± 2)·104 m− 3, respectively). In contrast, the culturable cells of B. subtilis drop down by a factor of 10 ((3 ± 1)·103 m− 3). It is worth knowing that the bioaerosol generators exert mechanical stress on bacteria during aerosolization, leading to the cell membrane’s rupture and the release of genomic DNA49,57. The more reduced culturability of B. subtilis, compared to E. coli and P. fluorescens, at t = 0 can be attributed to the distinct characteristics of their bacterial cell membranes: Gram-positive bacteria, in contrast to Gram-negative bacteria, lack an outer lipopolysaccharide membrane and the cell membrane and respiratory chain are the two locations susceptible to damage during the aerosolization process58.

In order to determine the lifetime of both total and culturable bacteria, the data were adjusted for the dilution factor, taking into account the flow rate of the WIBS instrument (0.3 L min− 1) and the duration of Andersen sampling to collect appropriate CFUs on Petri dishes (reported in the Supplement). Finally, the data of each experiment are fitted using the exponential function:

where C0 is the total or culturable bacteria at t = 0 and t is the total or culturable lifetime. The equation used to determine the lifetime of total bacteria in ChAMBRe is the same adopted in29. Furthermore, the identical equation may also be used for culturable bacteria. Specifically, the inactivation kinetics of culturable bacteria can be accurately represented by the well-established exponential inactivation equation formulated by59. This equation is also suitable for modelling the inactivation kinetics of single-strain populations, as suggested by60. Finally, our experimental results demonstrate a high level of concurrence with Eq. (1), which assumes a constant reduction rate of culturable bacteria rate. However, more complex models could not be evaluated using the available dataset.

The average and standard deviation of C0 and t of B. subtilis and P. fluorescens are reported in Table 1. These values can be compared with the results of E. coli (reported in51) and, shown here in Table 1 to make the comparison easier.

The total B. subtilis, P. fluorescens and E. coli average lifetime is around 115, 400 and 150 min respectively; these values agree with the data reported in38 where, for particles in the size interval 0.7–3 μm, the lifetime in ChAMBRe ranges from 1 to 7 h. In addition, at t = 0 and during all experiments, The WIBS data showed particles with an optical diameter of less than 2.5 μm, suggesting a low aggregation level (figure S1). In other words, these numbers depend essentially on the fluid dynamics inside the confined ChAMBRe environment.

The average culturable lifetime of B. subtilis and E. coli is similar, but P. fluorescens has an average culturable lifetime that is about half as long. In general, the average culturable lifetime for all bacteria is shorter than their average total lifetime, indicating that these cells struggle to survive in the air. The lifetime of culturable bacteria can be tentatively corrected for wall losses by considering the total lifetime, obtained by WIBS data, for each bacteria strain inside ChAMBRe. The final adjusted lifetime for culturable bacteria is therefore 65 ± 4, 23 ± 2 and 37 ± 7 min, for B. subtilis, P. fluorescens and E. coli, respectively. By this correction, we can roughly estimate the lifetime in open air, without the constraint’s characteristic of a confined ASC. A comparison between the adjusted and unadjusted culturable lifetimes shows that for E. coli and P. fluorescens, the values are similar within the error, while for B. subtilis, the adjusted value is approximately double the unadjusted value.

Experiments with NO and NO2

In the second batch of experiments, each bacterial strain was exposed to two different concentrations of NO and NO2 (900 ppb and 1200 ppb). The effect of these gases on E. coli, B. subtilis and P. fluorescens is illustrated in Fig. 5, showing the trends of CFU normalized at t = 0 for each bacteria strain under different ambient conditions. To accurately compare the trends of gases and baseline experiments, the data from the gas experiments were adjusted to reflect the varying dilution factors. Specifically, for NO and NO2, an additional gas monitor was used with a flow rate of 1 L min− 1, along with different Andersen sampling times to collect suitable CFUs on Petri dishes. The average and standard deviation of bacteria concentrations (# cm− 3) @ t = 0 of all experiments are reported in Table S2 of Supplement.

The experimental data can be fitted with exponential curves, described above, to calculate the average value of the lifetime of each viable bacteria strain at different gas concentrations. Table 2; Fig. 6 show the average culturable lifetimes and standard deviation of E. coli, B. subtilis and P. fluorescens, respectively. The average and standard deviation of T and RH and the number of whole experiment (i.e., inoculum characterization, bacteria injection and sampling) repetitions are reported.

Average culturable lifetime of NOx experiments, normalized to the value of baseline for all bacteria strains. The light blue rectangles mark the uncertainties of each normalized baseline. The P-value of T student test was calculated between pollutant experiments and baseline conditions for each bacteria strain. “NS” stands for “Not Significant”, * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01.

The lower concentration of NO did not show an impact on the bacteria’s culturability inside the chamber. However, at a concentration of 1200 ppb, NO reduced the culturability of E. coli, B. subtilis, and P. fluorescens of about 32%, 20%, and 26%, respectively. On the other hand, NO2 had a different effect on bacteria. Both concentrations of NO2 reduced the culturability of B. subtilis and P. fluorescens by about the same factor (on average about 57% and 68%, respectively). However, for E. coli, higher concentrations of NO2 increased the loss of culturability. It is important to note that NO2 reduced the bacteria culturability more than NO. This effect could be related to the reaction between NO2 and H2O, producing NO and nitric acid, a strong acid and a powerful oxidizing compound61. The literature contains limited studies on the interaction of these bacterial strains with NO and NO2: one of these studies demonstrated that the NO2 induced in P. fluorescens envelope alterations and decreased membrane integrity62; in another study63 several alterations in terms of reduced swimming motility and decreased swarming were observed when P. fluorescens were exposed to high NO2 concentration. The64 study demonstrated that, for the airborne bacterial strain P. fluorescens, NO2 is far more hazardous than NO at comparable doses. Finally, according to65, E. coli was significantly susceptible to the bactericidal effects of NOx in the gas phase.

Experiments with light

Several experiments with bacteria and solar simulator were performed and the comparison of the data collected in baseline conditions (dark) and with light are shown in Fig. 7. The atmospheric conditions inside the chamber for both baseline and light experiments were the same and Table 3 shows the average culturable lifetime of baseline and light conditions for all bacteria strains.

All bacteria showed a strong culturable lifetime reduction with light : the culturability reduction was found to be about 80%, 75% and 92% for E. coli, B. subtilis and P. fluorescens, respectively. All bacteria are strongly impacted by the solar simulator’s irradiance effect; light, particularly UV wavelengths, can inactivate a wide variety of microorganisms, thereby lowering the viability of microbial communities66,67. In addition, simulated solar irradiation is the most dominant factor in the aging process, followed by the combination of high RH and ozone68.

Finally, in the experiments, the relative humidity was maintained constant, but it has been demonstrated that it is the primary environmental factor affecting the UV inactivation rate of certain bacteria69. Specifically, at a constant UV exposure, the UV inactivation rate of airborne M. parafortuitum cells diminished by a factor of 4 as relative humidity rose from 40 to 95%.

Conclusion

This research addressed the quantitative impact of NO, NO2 and light conditions on the viability of three different bacteria strains in an atmospheric simulation chamber. The lifetime of the total (i.e. all viable, alive and dead) bacteria inside ChAMBRe of all strains in the baseline experiments resulted consistent with the data for particles in a size range of 0.7 to 3 μm, this indicating that such lifetime directly depended on the fluid dynamics within the ASC. Conversely, the culturable lifetime of all bacteria strains was reduced, indicating that these cells have challenges in sustaining their survival in the atmospheric environment.

The results regarding pollutants experiments indicated that NO2 had a greater impact on bacteria culturability than NO. A high concentration of NO2 decreased the lifetime of E. coli, B. subtilis, and P. fluorescens by approximately 70%, 53%, and 70% respectively. Conversely, the lower concentration of NO (900 ppb) did not impact bacteria culturability, while the higher concentration of NO (1200 ppb) reduced the lifetime of E. coli, B. subtilis, and P. fluorescens by about 32%, 20%, and 26%, respectively.

The solar simulator experiments revealed a significant abiotic effect of light on all bacterial strains, due to the inactivation of microorganisms by UV wavelengths.

The present encouraging results call for further investigations to determine whether pollutants and light can deactivate bacteria, in terms of culturability reduction. Our findings and the novel methodology pertain to pollutant concentrations that are rather arbitrarily chosen as references; yet, only rigorously evaluated dose-effect curves can yield pertinent environmental outcomes as threshold values. Understanding also how the pollutants and light affect the bacteria in terms of VBNC is crucial: the significance of VBNC is fundamental, especially for public health, as VBNC pathogens can go undetected in clinical and environmental samples, posing a concealed threat to public health. These pathogens can retain their virulence and cause infections once they become active again. Various techniques, such as viability stains like SYTO 9 and propidium iodide, flow cytometry, and metabolic activity assays such as ATP levels or reductase activity, can be used to measure the VBNC state. All these techniques require collecting bacteria from a liquid sample, for example, using an impinger. Understanding the VBNC state is vital for accurate microbial monitoring and for developing strategies to manage and control bacterial populations in different settings. The impact of other pollutant species will be addressed as well in future experimental campaigns.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

WHO. Air Pollution. Available online at: (2024). http://www.who.int/airpollution/en/

Jaenicke, R. Abundance of cellular material and proteins in the atmosphere. Science 308, 5718 (2005).

Bowers, R. M., McCubbin, I. B., Hallar, A. G. & Fierer, N. Seasonal variability in airborne bacterial communities at a high-elevation site. Atmos. Environ. 50, 41–49 (2012).

Gong, J., Qi, J., Yin, E. B. & Gao, Y. Concentration, viability and size distribution of bacteria in atmospheric bioaerosols under different types of pollution. Environ. Pollut.. 257, 113485 (2020).

Burrows, S. M., Elbert, W., Lawrence, M. G. & Pöschl, U. Bacteria in the global atmosphere – Part 1: review and synthesis of literature data for different ecosystems. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 9, 9263–9280 (2009).

Gandolfi, I., Bertolini, V., Ambrosini, R., Bestetti, G. & Franzetti, A. Unravelling the bacterial diversity in the atmosphere. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 97, 4727–4736 (2013).

Després, V. R. et al. Primary biological aerosol particles in the atmosphere: A review. Tellus B: Chem. Phys. Meteorol. 64, 15598 (2012).

Dugan, R. S. Board-invited review: Fate and transport of bioaerosols associated with livestock operations and manures. J. Animal Sci. 88(11), 3693–3706 (2010).

Min, W. C. Characteristics of atmospheric bacterial and fungal communities in PM2.5 following biomass burning disturbance in a rural area of North China plain. Sci. Total Environ. 651 (Part 2), 2727–2739 (2019).

Bigg, E. K., Soubeyrand, S. & Morris, C. E. Persistent after-effects of heavy rain on concentrations of ice nuclei and rainfall suggest a biological cause. ACP 15 (5), 2313–2326 (2015).

Failor, K. C. Ice nucleation active bacteria in precipitation are genetically diverse and nucleate ice by employing different mechanisms. ISME J. 12, 2740–2753 (2017).

Haowei, W. et al. Unveiling the crucial role of soil microorganisms in carbon cycling: A review. Sci. Total Environ. 909, 168627 (2024).

Ma, Y., Zhou, J., Yang, S., Zhao, Y. & Zheng, X. Assessment for the impact of dust events on measles incidence in Western China. Atmos. Environ. 157, 1–9 (2017).

Maki, T. et al. Long-range transport of airborne bacteria over East Asia: Asian dust events carry potentially nontuberculous Mycobacterium populations. Environ. Int. 168, 107471 (2022).

Moore, G., Hewitt, M., Stevenson, D., Walker, J. T. & Bennett, A. M. Aerosolization of respirable droplets from a domestic spa pool and the use of MS-2 coliphage and Pseudomonas aeruginosa as markers for Legionella Pneumophila. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 81, 2 (2015).

Nduba, V. et al. Mycobacterium tuberculosis cough aerosol culture status associates with host characteristics and inflammatory profiles. Nat. Commun. 15, 7604 (2024).

Jones, A. M. & Harrison, R. M. The effects of meteorological factors on atmospheric bioaerosol concentrations—a review. Sci. Total Environ. 326, 151–180 (2004).

Samake, A. et al. The unexpected role of bioaerosols in the oxidative potential of PM. Sci. Rep. 7, 10978 (2017).

Tang, J. The effect of environmental parameters on the survival of airborne infectious agents. J. R. Soc. Interface. 6, S737–S746 (2009).

Brotto, P. et al. Use of an atmospheric simulation chamber for bioaerosol investigation: a feasibility study. Aerobiologia 31, 445–455 (2015).

Hussey, S. J. K. et al. Air pollution alters Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pneumoniae biofilms, antibiotic tolerance and colonisation. Environ. Microbiol. 19, 5, 1868–1880 (2017).

Noda, J., Tomizawa, S., Takahashi, K., Morimoto, K. & Mitarai, S. Air pollution and airborne infection with mycobacterial bioaerosols: A potential attribution of soot. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 19, 717–726 (2021).

Gandolfi, I. et al. Spatio-temporal variability of airborne bacterial communities and their correlation with particulate matter chemical composition across two urban areas. Environ. Biotechnol. 99, 4867–4877 (2015).

Liang, Z. et al. Inactivation of Escherichia coli in droplets at different ambient relative humidities: effects of phase transition, solute and cell concentrations. Atmos. Environ. 280, 119066 (2002).

Siller, P. et al. Impact of air humidity on the tenacity of different agents in bioaerosols. PLoS ONE 19, 1 (2024).

Guo, L. et al. Population and single cell metabolic activity of UV-induced VBNC bacteria determined by CTC-FCM and D2O-labeled Raman spectroscopy. Environ. Int. 130, 104883 (2019).

Matallana-Surget, S., Meador, J. A., Joux, F. & Douki, T. Effect of the GC content of DNA on the distribution of UVB-induced bipyrimidine photoproducts. Photochem. Photobiol Sci. 7, 7, 794–801 (2008).

Sinha, R. P. & Häder, D. P. UV-induced DNA damage and repair: A review. Photochem. Photobiol Sci. 1 (4), 225–236 (2002).

Friedberg, E. DNA damage and repair. Nature 421, 436–440 (2003).

Xiao, X. et al. Evaluation of antibacterial activities of silver nanoparticles on culturability and cell viability of Escherichia coli. Sci. Total Environ. 794, 148765 (2021).

Gordienko, M. G. et al. Antimicrobial activity of silver salt and silver nanoparticles in different forms against microorganisms of different taxonomic groups. J. Hazard. Mater. 378, 120754 (2019).

Li, X. et al. Silver nanoparticle toxicity and association with the Alga Euglena gracilis. Environ. Sci. Nano, 6, 594–602 (2015).

Keer, J. T. & Birch, L. Molecular methods for the assessment of bacterial viability. J. Microbiol. Methods. 53, 2, 175–183 (2003).

Liu, J., Yang, L., Kjellerup, B. & Xu, Z. Viable but nonculturable (VBNC) state, an underestimated and controversial microbial survival strategy. Trends Microbiol. 31, 10 (2023).

Fakruddin, M., Mannan, S. B. & Andrews, S. Viable but nonculturable bacteria: Food safety and public health perspective ISRN microbiology, 2013, 703813 (2013).

Möhler, O. et al. The portable ice nucleation experiment (PINE): a new online instrument for laboratory studies and automated long-term field observations of ice-nucleating particles. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 14, 1143–1166 (2021).

Amato, P. et al. Survival and ice nucleation activity of bacteria as aerosols in a cloud simulation chamber. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 15, 6455–6465 (2015).

Massabò, D. et al. ChAMBRe: a new atmospheric simulation chamber for aerosol modelling and bio-aerosol research. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 11, 5885–5900 (2018).

Atkinson, R. W., Butland, B. K., Anderson, H. R. & Maynard, R. L. Long-term concentrations of nitrogen dioxide and mortality. Epidemiology 29 (4), 460–472 (2018).

Ruiz, N. & Silhavy, T. J. How Escherichia coli became the flagship bacterium of molecular biology. J. Bacteriol. 204, 9 (2022).

Silby, M. W., Winstanley, C., Godfrey, S. A. C., Levy, S. B. & Jackson, R. W. Pseudomonas genomes: diverse and adaptable. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 35, 652–680 (2011).

Ulrich, N. et al. Experimental studies addressing the longevity of Bacillus subtilis spores—The first data from a 500-year experiment. PLoS ONE. 13, 12 (2018).

Wei, X., Aggrawal, A., Bond, R. F., Latack, B. C. & Atwill, E. R. Dispersal and risk factors for airborne Escherichia coli in the proximity to beef cattle feedlots. J. Food. Prot. 86 (6), 100099 (2023).

Kaneshiro, E. S., Wyder, M. A., Wu, Y. P. & Cushion, M. T. Reliability of calcein acetoxy Methyl ester and ethidium homodimer or Propidium iodide for viability assessment of microbes. J. Microbiol. Methods. 17 (1), 1–16 (1993).

Diaper, J. P. & Edwards, C. The use of fluorogenic esters to detect viable bacteria by flow cytometry. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 77, 2, 221–228 (1194).

Porter, Edwards, J. C. & Pickup, R. W. Rapid assessment of physiological status in Escherichia coli using fluorescent probes. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 79, 4, 399–408 (1995).

Hiraoka, Y. & Kimbara, K. Rapid assessment of the physiological status of the polychlorinated biphenyl degrader Comamonas testosteroni TK102 by flow cytometry. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68 (4), 2031–2035 (2002).

Boulos, L., Prévost, M., Barbeau, B., Coallier, J. & Desjardins, R. L. I. V. E. /DEAD® BacLight™: Application of a new rapid staining method for direct enumeration of viable and total bacteria in drinking water. J. Microbiol. Methods. 37 (1), 77–86 (1999).

Danelli, S. G. et al. Comparative characterization of the performance of bio-aerosol nebulizers in connection with atmospheric simulation chambers. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 14, 4461–4470 (2021).

Vernocchi, V. et al. Characterization of soot produced by the mini inverted soot generator with an atmospheric simulation chamber. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 15, 2159–2175 (2022).

Vernocchi, V. et al. Airborne bacteria viability and air quality: a protocol to quantitatively investigate the possible correlation by an atmospheric simulation chamber. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 16, 22, 5479–5493 (2023).

Mainelis, G. et al. Design and performance of a single-pass bubbling bioaerosol generator. Atmos. Environ. 39, 19, 3521–3533 (2005).

Bintsis, T. Foodborne pathogens. AIMS Microbiol. 3, 3, 529–563 (2017).

Obasola, E. F., Ogunjobi, A. A. & Abiala, M. A. Falodun, O. I. Fate and transport of microorganisms in the air. In Aeromicrobiology 39–58 (2023).

Fahimipour, A. K. et al. Daylight exposure modulates bacterial communities associated with household dust. Microbiome 6, 175 (2018).

Liu, J., Yang, L., Kjellerup, B. V. & Xu, Z. Viable but nonculturable (VBNC) State, an underestimated and controversial microbial survival strategy. Trends Microbiol. 31, 10, 1013–1023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tim.2023.04.009 (2023).

Zhen, H., Han, T., Fennel, D. E. & Mainelis, G. A systematic comparison of four bioaerosol generators: affect on culturability and cell membrane integrity when aerosolizing Escherichia coli bacteria. J. Aerosol. Sci. 70, 67–79 (2014).

Thomas, R. J. et al. The cell membrane as a major site of damage during aerosolization of Escherichia coli. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77 (3), 920–9255 (2011). (2011).

Esty, J. R. & Meyer, K. F. The heat resistance of spores of B. botulinus and allied anaerobes. J. Infect. Dis. 31, 650–663 (1992).

Bevilacqua, A., Speranza, B., Sinigaglia, M. & Corbo, M. R. A focus on the death kinetics in predictive microbiology: benefits and limits of the most important models and some tools dealing with their application in foods. Foods 4, 565–580 (2015).

Clarke, S. I. & Mazzafro, W. J. Nitric acid. in ECT 3rd (ed. D. J. Newman) vol. 15, pp. 853–871 (Barnard and Burk, Inc, 2000).

Chautrand, T. et al. Gaseous NO2 induces various envelope alterations in Pseudomonas fluorescens MFAF76a. Nat. Sci. Rep. 12, 8528 (2022).

Kondakova, T. et al. Response to gaseous NO2 air pollutant of P.fluorescens airborne strain MFAF76a and clinical strain MFN1032. Front. Microbiol. 7, 1–12 (2016).

Chautrand, T. et al. Detoxification response of Pseudomonas fluorescens MFAF76a to gaseous pollutants NO2 and NO. Microorganisms 10 (8), 1576 (2022).

Sekimoto, K., Gonda, R. & Takayama, M. Effects of H3O+, OH-, O2-, nox- and nox for Escherichia coli inactivation in atmospheric pressure DC Corona discharges. J. Phys. D. 48, 30, 305401 (2015).

Hockberger, P. E. The discovery of the damaging effect of sunlight on bacteria. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B. 58, 2, 185–191 (2000).

Hobday, R. & Dancer, S. Roles of sunlight and natural ventilation for controlling infection: historical and current perspectives. J. Hosp. Infect. 84 (4), 271–282 (2013).

Kinahan, S. M. et al. Changes of fluorescence spectra and viability from aging aerosolized E. coli cells under various laboratory-controlled conditions in an advanced rotating drum. Aerosol Sci. Technol., 53(11), 1261–1276 (2019).

Peccia, J. and Hernandez M. Photoreactivation in Airborne Mycobacterium parafortuitum. Appl. Environ. Microbiol., 67(9), 4225–4232 (2001).

Funding

This research has been supported by PON PER-ACTRIS-IT (MURIT PON; project no. PIR_00015; “Per ACTRIS IT”), Blue-Lab 60 Net (FESR – Fondo Europeo Di Sviluppo Regionale Azione POR, Regione Liguria, Italy), IR0000032–ITINERIS, Italian Integrated Environmental Research Infrastructures System (D.D. n. 130/2022 - CUP B53C22002150006) funded by the EU (Next Generation EUPNRR, Mission 4 “Education and Research”, Component 2 “From research to business”, Investment 3.1, “Fund for the realisation of an integrated system of research and innovation infrastructures”) and the PNRR MUR Project ”Multi Risk sciEnce for resilienT commUnities undeR a changiNg climate (RETURN)” (grant no. PE00000005 CUP HUB B63D22000670006).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

EG, VV and FM thought up the study and performed the experiments with the contribution of EAE. MB developed the data acquisition. FM performed all data analysis with the contribution of DM and PP. TI supported the experiments with the solar simulator and FP helped with the development of ChAMBRe structure. EG, VV and FM wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed and commented the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gatta, E., Abd El, E., Brunoldi, M. et al. Viability studies of bacterial strains exposed to nitrogen oxides and light in controlled atmospheric conditions. Sci Rep 15, 10320 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-94898-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-94898-y