Abstract

Oral disorders are major global health issues, affecting 3.5 billion people and imposing significant economic burdens. This study analyzed the distribution and trends of oral disorder burden globally and in China from 1990 to 2021, aiming to inform resource allocation and prevention strategies. Data from the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) 2021 database were used to evaluate the incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability (YLDs) of oral disorders. All statistical analyses and data visualizations were conducted using R. In 2021, the burden of oral disorders in China accounted for a significant proportion of the global burden. The incidence, prevalence, and YLDs increased by 15.49%, 52.44%, and 86.86% respectively compared with 1990. The global burden also showed an upward trend during the same period. The relevant indicators in China are at a relatively low level, and disparities were observed among regions with different sociodemographic indices (SDI). Oral disorder burden is on the rise globally, with females, children, adolescents, and the elderly being the key affected groups. Regions with middle SDI bear a heavier burden. This study provides a scientific basis for the formulation of relevant policies and emphasizes the necessity of interventions for specific groups.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Oral disorders, which include deciduous tooth decay, permanent tooth decay, periodontal disease, edentulism, and other oral conditions, are prevalent health issues globally, affecting approximately 3.5 billion people worldwide1. These diseases not only impact basic functions such as chewing, breathing, and speech but also extend to the psychosocial dimensions affecting individuals’ self-confidence, well-being, and social interaction abilities2,3. The risk factors for oral disorders are closely associated with unhealthy lifestyle habits such as smoking, alcohol consumption, and high intake of free sugars, which are also common risk factors for non-communicable diseases like cardiovascular diseases, cancers, chronic respiratory diseases, and diabetes4.

The economic burden of global oral disorders is enormous, with far-reaching and extensive impacts. According to the World Economic Forum’s report The Economic Rationale for a Global Commitment to Invest in Oral Health, the annual treatment costs and productivity losses amount to $710 billion5. Over the past 30 years, the growth rate of oral disorder cases has exceeded population growth, particularly in low-income countries where the relative increase is the greatest6,7,8. Oral disorders have become one of the top 10 global disease burdens, with direct treatment costs accounting for 4.6% of global health expenditures9. In addition to medical costs, oral disorders also have broader impacts on GDP growth and the socioeconomic system due to the loss of labor and decline in productivity.

Although oral disorders are largely preventable, they are often overlooked in health policies10. Despite improvements in overall health with socio-economic and cultural development, oral disorders remain a widespread health issue11. The burden of oral disorders is unevenly distributed globally, with increasing incidence rates in low- and middle-income countries. This is related to the inequitable access to health maintenance resources, accessibility of health services, and the lack of oral health-related policies12. The World Health Organization (WHO) has long listed oral health as one of the ten standards of human health and emphasized that oral health should be firmly embedded in the non-communicable disease agenda, with oral health care interventions included in universal health coverage plans13.

In China, the burden of oral disorders is also heavy. According to the China Oral Health Development Report (2022), the prevalence of oral disorders such as caries, periodontal disease, tooth loss, and defects in the elderly is high, and the incidence of oral and maxillofacial malignant tumors is on the rise. Additionally, the rate of dental caries in children is also increasing. Furthermore, the distribution of oral medical resources in China is uneven, especially with a shortage of dentists14; in 2020, there were 15.7 dentists per 100,000 people in China, far below the numbers in countries like the United States, South Korea, and Japan.

Although existing studies have revealed the global prevalence and economic burden of oral health problems, most previous research on oral health has focused on single diseases or specific populations. However, the occurrence of oral diseases is influenced by multiple factors, including socioeconomic development, the distribution of medical resources, and lifestyle. There are differences in prevention and control strategies and medical accessibility among countries with different levels of socioeconomic development, leading to diverse patterns of disease burden changes. Therefore, studying the long-term trends of oral disorders in the context of the socioeconomic background is crucial for developing targeted policies.

This study employs the most recent data from the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) 2021, encompassing prevalence, incidence, and years lived with disability (YLDs) from 1990 to 2021. We analyzed the epidemiological trends and burden changes of oral disorders across multiple dimensions, including sex, age, region, and the sociodemographic index (SDI), from both global and Chinese perspectives. As a representative of developing nations, China contends with the dual challenges of unequal distribution of healthcare resources and a growing burden of disease, all while experiencing swift economic advancement. This study attempts to reveal the characteristics of oral health burden under different socioeconomic backgrounds and explore the relationship between economic development, the allocation of medical resources, and disease burden through comparative analyses between the global context and China. It aims to fill the gaps in existing research and provide a scientific basis for formulating effective health policies and resource allocation strategies.

Methods

Data sources

The data for this study primarily comes from the GBD 2021 database, which is led by the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) at the University of Washington. The GBD 2021 database currently primarily utilizes Disease Modeling Meta-Regression version 2.1 (DisMod-MR 2.1) as its estimation method. DisMod-MR 2.1 is a Bayesian meta-regression tool designed to integrate data from multiple sources—such as health surveys, literature, systematic reviews, clinical studies, and mortality records—to generate estimates of incidence, prevalence, and YLDs for diseases and injuries at the global, regional, and national levels. This tool addresses data sparsity and heterogeneity through Bayesian methods, ensuring the consistency and accuracy of the estimates. In handling missing data and regional variability, DisMod-MR 2.1 employs a hierarchical Bayesian model, incorporating data from different regions and populations into a unified framework. This allows for borrowing information from other regions in areas with sparse data, thereby enhancing the robustness and reliability of the estimates15. The model strengthens its ability to model regional variability by integrating data from various sources and correcting for differences in measurement methods and case definitions. This study particularly focuses on the burden of oral disorders, including their prevalence, incidence, and YLDs, and considers key factors such as geographical location, age, sex, and the SDI.

Data extraction

Specifically, all these data can be accessed through the Global Health Data Exchange (GHDx) query tool (http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-results-tool). This study extracted oral disorder data from 1990 to 2021 for global, SDI regions, and countries. The data were analyzed at the population level to explore the distribution among different population groups, including age, sex, and specific subgroups. Individuals were categorized into 18 age groups (every 5 years starting from 10 years old up to 94 years old and above 95 years old). Disability-Adjusted Life Year (DALY) is an important population metric in GBD, representing the sum of Years of Life Lost (YLL) and YLD16. However, deaths directly caused by oral disorders are not common; the GBD 2021 study only considers the health loss brought by oral disorders and does not account for oral disorders mortality. Therefore, this study only uses YLDs. SDI is a composite index that includes gross domestic product per capita, mean years of schooling, and fertility rate17. The SDI value reflects social development and is an important variable for assessing a region’s disease burden and health development. The GBD study divides 204 countries and regions into 5 SDI quintiles (low, low-middle, middle, middle-high, and high)18. According to the latest report on SDI regions from the GBD database, China is categorized as a middle-high SDI region19.

Analytical methods

When comparing changes over time with different age structures, standardization is necessary. The unit of standardized rates is per 100,000 people, and age-standardized rate (ASR) trends can well represent changes in disease patterns within populations and can serve as clues to changing risk factors. We calculated the estimated annual percentage change (EAPC) to assess the temporal trends of ASR over the past 32 years. EAPC is a summary measure and widely used metric for ASR trends over a specific time interval. The formula is set as follows: Y = α + βX + ε. In this linear regression model, X represents the calendar year, Y represents the natural logarithm of ASR, and ε represents the error term. EAPC is assessed as 100 × (exp(β) − 1)20. We also calculated the 95% confidence interval (CI) for β using the linear regression model mentioned above. The 95% CI for β is calculated as \(\beta _{{{\text{CI}}}} = \beta \pm {\text{ t}}_{{\alpha /{\text{2}},{\text{n}} - {\text{2}}}} \times {\text{SE}}\left( \beta \right)\) . Here, \({\text{t}}_{{\alpha /{\text{2}},{\text{n}} - {\text{2}}}}\) is the critical value of the t-distribution, α is the significance level (usually 0.05), n is the sample size, and SE(β) is the standard error of β. We also calculated the associated 95% CI using the aforementioned linear regression model. If the estimated value and the 95% CI are both below 0, it indicates a downward trend. Conversely, if the estimated value and the 95% CI are both above 0, it indicates an upward trend in ASR21.

In addition, time series analysis methods were employed to identify patterns of change in disease burden over time and potential cyclical trends. Concurrently, linear regression models were utilized to fit the temporal variations in disease burden, which were validated through significance tests. The regression coefficient (rho) was used to assess the goodness of fit.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses and data visualizations were conducted using R (version 4.4.1). Descriptive statistics are presented as means with 95% uncertainty intervals (UI). For data visualization and trend analysis, the R packages primarily used were ggplot2, cowplot, data.table, and ggsci. The calculation of EAPC involved the use of Dplyr, flextable, and officer. The correlation analysis related to the SDI combined Reshape and ggrepel. Age trend analysis was based on Tidyverse, Bstfun, gt, gtExtras, and MetBrewer. For trend analysis, a p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Global and China trend analysis

In 2021, the number of incidence cases, prevalence cases, and YLDs of oral disorders in China accounted for 14.10%, 16.25%, and 18.93% of the global cases, respectively. Compared to 1990, the number of incidence cases, prevalence cases, and YLDs in China increased by 15.49%, 52.44%, and 86.86%, respectively. Globally, the burden of oral disorders showed a similar trend to China, with increases in the number of incidence cases, prevalence cases, and YLDs, rising by 35.55%, 52.44%, and 80.90%, respectively (Table 1). In addition, the age-standardized incidence rate (ASIR), age-standardized prevalence rate (ASPR), and age-standardized years lived with disability rate (ASLR) for oral disorders in China in 2021 were 44,580.89, 39,192.93, and 233.19 per 100,000 individuals, respectively. Compared to 1990, the ASIR in 2021 increased, while ASPR and ASLR decreased. Globally, the burden of oral disorders showed a similar trend to China (Tables 1 and 2).

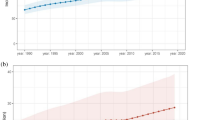

Upon specific analysis of the changes in disease burden from 1990 to 2021, both China and globally exhibited a steady increasing trend in the number of incidence cases, prevalence cases, and YLDs. Figure 1 shows that the ASIR of oral disorders in China initially declined, followed by an increase, and then experienced another decline, with inflection points occurring in 2000 and 2015. The ASPR and ASLR fluctuated within a certain range. Similarly, the overall trend of the ASIR for global oral disorders showed a slight initial decrease, with an inflection point in 2000, followed by an upward shift. The ASPR and ASLR followed a pattern similar to that observed in China.

Trends in the incidence and ASIR (A), prevalence and ASPR (B), YLDs and ASLR (C) of oral disorders in China and globally from 1990 to 2021. In the figure, the bar chart represents the trend in the number of cases, while the line chart represents the trend in the age-standardized rate. The years of inflection points are marked with black circles. YLDs: years lived with disability.

Population distribution analysis

Observation of the sex distribution revealed that in 2021, there was slight difference between males and females in terms of the incidence and prevalence burden of oral disorders. However, the burden of YLDs was higher in females than in males. Globally, the number of YLDs cases was 12,492,138 (95% UI: 7,601,270–18,517,950) for females and 10,747,282 (95% UI: 6,313,212–16,513,740) for males. The ASLR was 287.52 (95% UI: 173.37–429.65) per 100,000 for females and 263.40 (95% UI: 155.33–402.94) per 100,000 for males (Fig. 2).

Analyzing the age distribution, the incidence rate of oral disorders was predominantly observed in children and adolescents (10–24 years old). In China, the 10–14 age group had the highest burden, with an incidence rate of 55,712.45 (95%UI: 26,803.70–116,294.35) per 100,000 people. Globally, the highest burden was also in the 10–14-year-old group, at 60,487.79 (95%UI: 35,773.76–104,439.02) per 100,000 people. The prevalence rate, on the other hand, was primarily concentrated in the elderly population (50 years and older). In China, the age group with the highest prevalence burden was 95 years and above, at 63,908.00 (95%UI: 56,292.00–72,140.98) per 100,000 people, while globally, the highest burden was in the 80-84-year-old group, at 64,335.01 (95%UI: 58,980.38-68,805.70) per 100,000 people. The rate of YLDs was mainly concentrated in individuals aged 75 and above. In China, the highest burden was in the 95 years and above age group, with 1,404.46 (95%UI: 905.17–1,971.72) YLDs per 100,000 people, whereas globally, the 90-94-year-old group had the highest burden, at 1,195.06 (95%UI: 770.22–1,689.05) per 100,000 people (Fig. 3, Supplementary Table 1). The number of incidence cases was also highest in children and adolescents (10–29 years old). In China, the age group with the highest burden was 10–14 years old, with 48,020,207 (95%UI: 23,102,901–100,237,538) cases, while globally, the highest burden was seen in the same age group, with 403,233,325 (95%UI: 238,480,722 –696,228,051) cases. The number of prevalence cases was predominantly concentrated in the middle-aged and young adult population (25–49 years old). In China, the highest burden was in the 50-54-year-old group, with 58,308,631 (95%UI: 48,473,547–67,086,770) cases, while globally, the highest burden occurred in the 35-39-year-old group, with 281,178,192 (95%UI: 227,446,545–336,373,457) cases. YLDs were most prevalent among the elderly (50–69 years old). In China, the 65–69 age group had the most YLDs at 541,965 (95%UI: 330,153–823,502), and globally, the same age group had the highest YLDs at 2,169,029 (95%UI: 1,324,172–3,222,570) (Fig. 3, Supplementary Table 1).

Further analysis of the rate trends of oral disorders in China from 1990 to 2021 by age group showed that for incidence rates, each age groups between 10 and 79 years old all experienced a sudden sharp increase during the period of 2001–2006. Subsequently, the two age groups of 65–74 years old would go through a process of decline and then rise, with the lowest peak in 2015. The age groups of 75 years old and above generally showed a trend of first increasing and then decreasing, with the three age groups of 75–89 years old reaching their peak in 2005. For prevalence rates, the overall trend for 10–14 years old and 20–24 years old was a decline, while the overall trend for 15–19 years old was an increase. The various age groups between 25 and 74 years old showed a similar fluctuating trend, with a significant increase in the years 2000–2005 and 2010–2015, and the various age groups of 80 years old and above also showed a similar fluctuating trend, with a rapid increase in the years 2015–2020. For YLDs rates, the age group of 70–74 years old was special, showing an increasing trend from 1990 to 2010, while the trends of other age groups followed a pattern similar to prevalence (Fig. 4).

Analysis based on countries and SDI regions

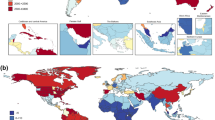

In the international comparison of ASR burden for oral disorders, Indonesia had the highest ASIR, followed by Brazil and Cambodia. The top three countries with the highest ASPR burden were Bolivia, Peru, and Ecuador. The countries with a higher ASLR burden were Bolivia, Peru, and Brazil. China’s ASIR, ASPR, and ASLR for the total population were at a relatively low middle level globally (Fig. 5).

Further comparison of incidence, prevalence, and YLDs burden between China and 5 SDI regions (Fig. 6). From the perspective of ASR, the middle SDI had the highest ASIR and ASLR, and the low SDI had the highest ASPR. In terms of numbers, the middle SDI had the heaviest burden in all indicators, and in addition, the low-middle SDI region and the high-middle SDI region also had a relatively heavy burden. At the same time, we can observe that the number of oral disorders in China occupies a large proportion in the high-middle SDI region.

We explored the association between the burden of oral disorders and SDI in China and globally from 1990 to 2021 (Fig. 7A–C). The results showed that the ASIR of oral disorders in China and globally was significantly positively correlated with SDI (P < 0.05). In terms of the strength of the correlation, the correlation between China’s ASIR burden and SDI was greater than the global correlation. Globally, there was a significant negative correlation between ASPR, ASLR, and SDI (P < 0.05). However, the correlation between China’s ASPR, ASLR, and SDI was not statistically significant. In addition, we described the correlation between ASR and SDI in 204 countries and regions in 2021 (Fig. 7D–F). ASR initially increased and then decreased with the rise of SDI. Although ASPR fluctuated with the increase of SDI, the overall trend was similar. Observing China’s position, its ASIR, ASPR, and ASLR were all below the expected level.

The association between ASIR (A), ASPR (B), ASLR (C) and SDI in oral disorders in China and globally from 1990 to 2021, and the ASIR (D), ASPR (E), ASLR (F) of oral disorders in 204 countries and regions in 2021 by sociodemographic index. The black line is the adaptive association fitted based on all data points using adaptive Loess regression. Roh is the regression coefficient, and p-value is for significance analysis. The red five-pointed star marks the location of China. YLDs: years lived with disability.

Discussion

This study employed the latest GBD 2021 data, with incidence, prevalence, and YLDs as metrics, to analyze the trends in the burden of oral disorders in China and globally from 1990 to 2021. The study found that the global ASIR for oral disorders has shown a slight upward trend since 1990, while ASPR and ASLR remained stable. In China, the number of incidence cases, prevalence cases, and YLDs account for a significant proportion globally. Compared with 1990, the ASIR in 2021 increased, while the ASPR and ASLR decreased. However, the sustained growth in the number of incident cases, prevalence cases, and YLDs globally reflects a heavy burden of oral disorders.

This phenomenon is associated with population growth and aging, as well as an increase in sugar consumption22,23,24. Moreover, chronic oral disorders such as periodontal disease and dental caries have a particularly significant impact on incidence and prevalence25. Periodontal disease is a chronic inflammatory condition that progresses slowly and insidiously. Early symptoms, such as gum bleeding, are often overlooked, and patients often fail to recognize the severity of the condition until it has progressed to serious consequences like alveolar bone resorption and tooth mobility26. Dental caries also has a chronic progressive nature, evolving from early superficial caries to deep caries, and further leading to complications such as pulpitis and periapical periodontitis27. Due to the lack of prominent symptoms, patients often fail to seek medical attention in a timely manner. Furthermore, these diseases are prone to recurrence. If patients do not maintain good oral hygiene after treatment, the condition is likely to reoccur. These factors contribute to the sustained high prevalence over the long term.

To prevent the further exacerbation of oral problems, it is necessary to improve oral health services, implement early diagnosis to control disease progression, and carry out effective preventive measures. Early detection and treatment of dental caries can prevent the spread of lesions, while basic periodontal disease treatments such as scaling and root planing can control the development of the condition28. Of course, the advancement of medical technology today also aids in disease control. Advanced imaging techniques, such as digital radiographs and cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT), can more precisely visualize the fine structures of teeth, periodontal tissues, and the jawbone. This enables doctors to detect hidden lesions in the early stages of disease, thereby significantly reducing the rate of missed diagnoses. For example, CBCT technology can identify early root caries or periodontal pocket formation that may be missed by traditional two-dimensional imaging. This allows for intervention at a reversible stage (e.g., non-surgical treatment of superficial caries), preventing the lesion from progressing to a severe condition that requires root canal treatment or tooth extraction29. As a result, the burden of oral disorders can be reduced. Governments should further promote balanced diets and reduce sugar consumption to address oral health issues at the source.

In terms of sex distribution, females bear a heavier burden of oral disorders. However, the female population (689 million) is lower than the male population (723 million), thus ruling out the influence of population factors on the differences in oral disorder burden between sexes. Women have a higher overall YLDs, which is associated with their longer life expectancy and more frequent utilization of oral health services30. Additionally, factors such as dietary habits (e.g., preference for sweets), the early eruption of primary teeth in girls, and fluctuations in hormone levels may contribute to this outcome31. Therefore, we can introduce specialized oral health education programs for women, or provide women - exclusive regular oral examination plans or subsidy policies as intervention measures.

In terms of age distribution, oral disorders affect individuals across all age groups, but the incidence is highest among children and adolescents. This is primarily associated with dental caries and other diseases caused by behaviors such as frequent sugar intake and irregular tooth brushing in this population32. Among the elderly, periodontal disease and edentulism affect the quality of life of the older population33. As age increases, the overall health status of the elderly population influences the prognosis of oral disorders, thereby leading to changes in the incidence of YLDs. Previous studies have indicated that the burden of dental caries and periodontal disease is expected to shift from the adult population to the elderly population34. For China, the intensification of population aging will make this trend more pronounced. From an economic perspective, the shift in disease burden will have a significant impact on the allocation of medical resources and the social security system, leading to an increase in medical insurance expenditures and a growing demand for long-term care.

In light of these findings, corresponding prevention and control policies need to be formulated. For children and adolescents, school-based oral health education should be strengthened, integrated into the curriculum and regularly promoted to enhance the health awareness of both students and their parents. The government can collaborate with the private sector through public financial allocations (for example, by establishing public-private partnerships with oral care brands or medical institutions) to set up oral health clinics in community health centers and schools. These clinics can offer free or discounted examinations and treatments, such as fissure sealants and fluoride applications for caries prevention. Additionally, the government should regulate the sugar content in children’s food and limit the advertising of high-sugar foods to guide healthy eating habits. For the elderly, a comprehensive oral health record system should be established. Regular community screenings should be organized. Medical institutions should be encouraged to provide services such as periodontal disease treatment and denture restoration, and these services should be covered by medical insurance. Medical institutions should also be encouraged to collaborate with elderly care facilities. By leveraging government subsidies and funding from non-profit organizations, home-based medical services can be provided. Knowledge training should also be conducted to raise awareness of preventive care.

In 2021, when comparing regions by the SDI, areas with middle SDI bore a heavier burden across various indicators. From the predictive analysis of SDI categorizations for 204 countries and regions, the ASR showed a trend of initially increasing and then decreasing with the rise in SDI. Due to economic and social factors, residents in regions with lower SDI may not have timely access to adequate oral health services, which can reduce the recording and reporting of oral disorders to some extent35. Regions with higher SDI typically have richer health resources and higher accessibility to health services, and the public has a greater awareness of oral health, thereby reducing the incidence of oral disorders11. Different exposures to risk factors can also lead to disparities in the burden of oral disorders36. Middle SDI regions may be in a transitional stage of economic development; although they have some economic growth, compared with regions of high SDI, their resources and infrastructure are still insufficient to provide adequate oral health services, thus showing a higher burden. In addition to economic factors, cultural factors (such as dietary habits and the consumption of traditional foods) are also important factors affecting oral health. In middle SDI regions, the intake of high-sugar and low-fiber foods is relatively common in diets, which may further exacerbate the burden of oral disorders. Therefore, for developing countries, it is imperative to strengthen the construction of medical infrastructure, increase investment in preventive policies, and formulate oral health promotion strategies that are in line with the local cultural context.

The correlation analysis between SDI and the burden of oral disorders from 1990 to 2021 indicates that globally, the ASIR of oral disorders is significantly positively correlated with SDI. However, in China, the correlation between the ASPR and ASLR and SDI is not significant, which may suggest that China faces some unique challenges in oral health services that require further research and targeted strategies. In international comparisons, China’s ASIR, ASPR, and ASLR are at a relatively low medium level globally. This phenomenon can be attributed to China’s efforts in recent years. China has issued the “Healthy China 2030” Planning Outline and the Action Plan for Oral Health (2019–2025). The reports emphasize prevention as the priority and promote a strategy that combines the entire population with key population groups37. Moreover, China also encourages and supports the development of the oral medical industry, such as implementing routine and institutionalized centralized bulk purchasing of dental implant products, and carrying out special governance of charges for oral implant medical services and the prices of consumables, focusing on reducing the medical expenses burden on consumers38.

Nevertheless, China’s oral medical system still faces several challenges, such as the uneven distribution of medical resources and a shortage of specialized personnel. Private institutions account for as high as 69.8% of China’s oral medical market, far exceeding public institutions14. Moreover, urban areas have significantly more oral medical resources than rural areas. Data shows that rural oral medical institutions account for only 22% of the total39. This affects the early diagnosis and treatment of oral disorders. Therefore, China should also strengthen the construction of oral medical resources in rural and western regions, promote the flow of oral medical resources to areas with insufficient resources, continue to enhance oral health education, facilitate the clinical application of oral medical research achievements, and improve the quality and efficiency of medical services.

This study, through a systematic comparison of the characteristics of oral disorders in China and globally, reveals unique differences in oral health between China and other regions of the world. The study emphasizes the necessity of targeted interventions and highlights key populations that should be prioritized. However, there are certain limitations. First, the data sources of the GBD database may be biased, especially in low-income and underdeveloped areas. Health monitoring systems in these regions are relatively weak, and low disease diagnosis rates or insufficient reporting rates may lead to a systematic underestimation of disease burden. In addition, some indicators in the GBD data are highly dependent on model estimates, which introduces additional uncertainty. Second, this study lacks the inclusion analysis of socioeconomic covariates, such as income level, education level, and accessibility of medical resources, which are important factors. Third, this study uses the GBD standard population rather than a China-specific population as the analytical benchmark. Although this facilitates comparisons at the international and global levels, given China’s higher degree of population aging, it may lead to an underestimation of disease burden. Lastly, this study is cross-sectional in design and is unable to conduct in-depth analysis of influencing factors or draw causal conclusions. Therefore, future studies should focus on the relationship between oral disorders and lifestyle habits (such as smoking, alcohol consumption, and high-sugar diets), assessing their specific impacts on the health of different populations. In-depth analysis of socioeconomic covariates and resource allocation equity should be conducted to explore strategies for policy interventions to optimize resource allocation. Finally, by integrating the common risk factors of oral disorders and non-communicable diseases, research on comprehensive multi-disease management models should be carried out to promote the overall improvement of health promotion efficiency.

Conclusion

This study comprehensively analyzed the burden of oral disorders in the world and China from 1990 to 2021, showing an overall upward trend, which highlights the urgency of prevention and control. In terms of sex, the burden is heavier for females, and we need to pay attention to the differentiated needs of sex. The characteristics of specific age groups are distinct. The high incidence among children and adolescents calls for early prevention, while the high prevalence and YLD rates among the elderly require optimized services and management. Regions with middle SDI bear a heavier burden. This study provides a basis for the formulation of relevant policies. Future research should further explore influencing factors and optimize resource allocation to improve global oral health levels and reduce the burden.

Data availability

The data used in this study are freely available from the Global Health Data Exchange (GHDx) website (http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-results-tool). The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- GBD:

-

Global burden of disease

- YLDs:

-

Years lived with disability

- SDI:

-

Sociodemographic index

- ASR:

-

Age-standardized rate

- ASIR:

-

Age-standardized incidence rate

- ASPR:

-

Age-standardized prevalence rate

- ASLR:

-

Age-dtandardized years lived with disability rate

- EAPC:

-

Estimated annual percentage change

- CI:

-

Confidence intervals

- UI:

-

Uncertainty intervals

- DisMod-MR 2.1:

-

Disease Modeling Meta-Regression version 2.1

References

Shoaee, S. et al. Global, regional, and National burden and quality of care index (QCI) of oral disorders: a systematic analysis of the global burden of disease study 1990–2017. J. BMC Oral Health 24, 116 (2024).

Wang, Y. et al. Social support, oral health knowledge, attitudes, practice, self-efficacy and oral health-related quality of life in Chinese college students. J. Sci. Rep. 13, 12320 (2023).

Oancea, R. et al. Influence of depression and self-esteem on oral health-related quality of life in students. J. J. Int. Med. Res. 48, 300060520902615 (2020).

Benzian, H., Daar, A. & Naidoo, S. Redefining the non-communicable disease framework to a 6 x 6 approach: incorporating oral diseases and sugars. J. Lancet Public. Health. 8, e899–e904 (2023).

World Economic Forum. The economic rationale for a global commitment to invest in oral health (World Economic Forum, 2024). https://www.weforum.org/reports/the-economic-rationale-for-a-global-commitment-to-invest-in-oral-health.

Luan, Y. et al. Universal coverage for oral health care in 27 low-income countries: a scoping review. J. Glob. Health Res. Policy. 9, 34 (2024).

Dye, B. A. The global burden of oral disease: research and public health significance. J. J. Dent. Res. 96, 361–363 (2017).

Jain, N., Dutt, U., Radenkov, I. & Jain, S. WHO’s global oral health status report 2022: actions, discussion and implementation. J. Oral Dis. 30, 73–79 (2024).

Listl, S., Galloway, J., Mossey, P. A. & Marcenes, W. Global economic impact of dental diseases. J. J. Dent. Res. 94, 1355–1361 (2015).

Fisher, J. et al. Achieving oral health for all through public health approaches, interprofessional, and transdisciplinary education. J. Nam. Perspect. (2023).

Tu, C. et al. Burden of oral disorders, 1990–2019: estimates from the global burden of disease study 2019. J. Arch. Med. Sci. 19, 930–940 (2023).

Duangthip, D. & Chu, C. H. Challenges in oral hygiene and oral health policy. J. Front. Oral Health 1, 575428 (2020).

Wolf, T. G., Cagetti, M. G., Fisher, J. M., Seeberger, G. K. & Campus, G. Non-communicable diseases and oral health: an overview. J. Front. Oral Health 2, 725460 (2021).

Sun, X. Y. et al. Report of the National investigation of resources for oral health in China. J. Chin. J. Dent. Res. 21, 285–297 (2018).

Collaborators GBDT. Global, regional, and National age-specific progress towards the 2020 milestones of the WHO end TB strategy: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2021. J. Lancet Infect. Dis. 24, 698–725 (2024).

Li, J. et al. Global, regional, and National total burden related to hepatitis B in children and adolescents from 1990 to 2021. J. BMC Public. Health 24, 2936 (2024).

Liu, P. et al. Global, regional, and National burden of pancreatitis in children and adolescents. J. United Eur. Gastroenterol. J. (2024).

Bai, Z. et al. The global, regional, and National patterns of change in the burden of congenital birth defects, 1990–2021: an analysis of the global burden of disease study 2021 and forecast to 2040. J. EClinicalMedicine 77, 102873 (2024).

Global Burden of Disease Study 2021 (GBD 2021) Socio-Demographic Index (SDI) 1950–2021 [database on the Internet]. Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) (2024).

Wang, Y. et al. Global burden of liver cirrhosis 1990–2019 and 20 years forecast: results from the global burden of disease study 2019. J. Ann. Med. 56, 2328521 (2024).

Zhang, C., Zi, S., Chen, Q. & Zhang, S. The burden, trends, and projections of low back pain attributable to high body mass index globally: an analysis of the global burden of disease study from 1990 to 2021 and projections to 2050. J. Front. Med. (Lausanne) 11, 1469298 (2024).

Cronan, C. S. The challenges of human population growth. In Ecology and Ecosystems Analysis (ed. Cronan, C. S.) 251–256 (Springer Nature, 2023).

Shanmugasundaram, S. & Karmakar, S. Excess dietary sugar and its impact on periodontal inflammation: a narrative review. J. BDJ Open. 10, 78 (2024).

Federation, F. D. I. W. D. Oral health for healthy ageing. J. Int. Dent. J. 74, 171–172 (2024).

AlJasser, R. et al. Association of oral health awareness and practice of proper oral hygiene measures among Saudi population: a systematic review. J. BMC Oral Health 23, 785 (2023).

Sengupta, A., Uppoor, A. & Joshi, M. B. Metabolomics: paving the path for personalized periodontics—a literature review. J. J. Indian Soc. Periodontol. 26, 98–103 (2022).

Farges, J. C. et al. Dental pulp defence and repair mechanisms in dental caries. J. Mediators Inflamm. 2015, 230251 (2015).

Lee, Y. Diagnosis and prevention strategies for dental caries. J. J. Lifestyle Med. 3, 107–109 (2013).

Shah, N., Bansal, N. & Logani, A. Recent advances in imaging technologies in dentistry. J. World J. Radiol. 6, 794–807 (2014).

Pinto Rda, S., Matos, D. L. & de Loyola Filho, A. I. Characteristics associated with the use of dental services by the adult Brazilian population. J. Cien Saude Colet 17, 531–544 (2012).

Lukacs, J. R. & Largaespada, L. L. Explaining sex differences in dental caries prevalence: saliva, hormones, and life-history etiologies. J. Am. J. Hum. Biol. 18, 540–555 (2006).

Moores, C. J., Kelly, S. A. M. & Moynihan, P. J. Systematic review of the effect on caries of sugars intake: ten-year update. J. J. Dent. Res. 101, 1034–1045 (2022).

Chan, A. K. Y. et al. Diet, nutrition, and oral health in older adults: A review of the literature. J. Dent. J. (Basel) 11, 785 (2023).

Elamin, A. & Ansah, J. P. Projecting the burden of dental caries and periodontal diseases among the adult population in the united Kingdom using a multi-state population model. J. Front. Public. Health 11, 1190197 (2023).

Osuh, M. E. et al. Oral health in an urban slum, Nigeria: residents’ perceptions, practices and care-seeking experiences. J. BMC Oral Health 23, 657 (2023).

Petersen, P. E., Bourgeois, D., Ogawa, H., Estupinan-Day, S. & Ndiaye, C. The global burden of oral diseases and risks to oral health. J. Bull. World Health Organ. 83, 661–669 (2005).

Zhou, X. et al. Oral health in China: from vision to action. J. Int. J. Oral Sci. 10, 1 (2018).

National Medical Security Administration. The notice on special governance of charges for oral implant medical services and prices of consumables. https://www.nhsa.gov.cn/art/2022/8/18/art_113_8868.html (2022).

Qi, X., Qu, X. & Wu, B. Urban-Rural disparities in dental services utilization among adults in China’s megacities. J. Front. Oral Health 2, 673296 (2021).

Funding

This work was supported by the Natural science foundation of Fujian province (No. 2024J011066); Fujian Provincial Health Technology Project (Grant number: 2022GGA032); Beijing Xisike Clinical Oncology Research Foundation (Grant number: Y-Gilead2024-PT-0047); Fujian Cancer Hospital In-Hospital High-Level Talent Training Project (Grant number: 2024YNG07).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ZH conceived and designed the study. ZH and PZ contributed to data collection and quality control. LZ, XQ and PL analyzed the data. ZP performed the statistical analysis. PZ and XQ wrote the manuscript. All authors have read and approved this manuscript. All authors have reviewed and approved the finalmanuscript for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

This study utilized publicly available data from the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) 2021 study, which does not require specific ethics approval or individual consent, as all data were de-identified and aggregated. Therefore, no additional ethical approval or consent to participate was necessary.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zheng, P., Qiu, X., Zhang, L. et al. Comparative analysis of oral disorder burden in China and globally from 1990 to 2021 based on GBD data. Sci Rep 15, 10061 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-94899-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-94899-x