Abstract

Ensuring the stability of faults near a tunnel is crucial for safety during excavation. This study presents a comprehensive numerical parametric analysis to evaluate fault stability in the context of tunnel construction. The analysis examines several key parameters, including fault mechanical properties, tunnel depth, fault angle, tunnel size, the distance between the fault and tunnel, and the initial stress state of the surrounding rock. These factors significantly affect stress distribution and potential fault movement, which are critical for maintaining tunnel stability. The findings emphasize the importance of specific factors, such as fault angle, the ratio of tunnel size to fault distance, and the initial stress state, in determining fault stability. To account for the interaction between these variables, a dimensionless parameter is developed, incorporating all these factors into a simplified metric for assessing the factor of safety in fault stability. A strong correlation between this dimensionless parameter and the factor of safety is established, offering a reliable method with minimal error. Finally, a case study is presented to verify the proposed safety approach, demonstrating its ability to accurately predict both the factor of safety and the location of fault slipping.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The construction of tunnels is increasingly essential to meet the rising demands of transportation and mining. The stability assessment of a potential tunnel, particularly those excavated under complex geological conditions, is a critical aspect of tunnel design1. The presence of a fault (a geological structure)2 near the location of the tunnel creates a two-way interaction with the stability of the tunnel. On the one hand, the fault could induce a concentration of shear stresses near the fault plane, which can alter the stress state around the potential location of the tunnel3,4. On the other hand, tunnel excavation alters the surrounding stress field, potentially leading to shear rupture and affecting fault stability5,6,7. Depending on several parameters, such as in situ stress, rock type, fault geometry, and distance between the tunnel and the fault, a part of the fault may reach its maximum shear strength while other parts may remain stable. The activation of the fault slipping along the discontinuity can cause damage to the surrounding rock mass, disturbance of the lining and bolt systems, and, in deep tunnels, cause a significant release of energy, potentially resulting in the rock burst phenomenon8,9.

Analytical solutions for the evolution of normal and shear stresses after excavation of tunnels have been developed for different configurations in terms of stress state, tunnel shape, and lining condition. In particular, Einstein and Schwartz10 introduced a solution for a lined circular tunnel in an elastic medium under anisotropic stress conditions. Wang et al.11 proposed an analytical solution for elliptical cross-section tunnels in rheological rock accounting for sequential excavation. Vitali et al.12 introduced an analytical solution for tunnel excavation in anisotropic ground taking into account the geostatic pressure. On the other hand, various numerical modeling techniques were applied to assess the influence of excavation near faults. The Finite Element Method (FEM) is applied by Sabagh and Ghalandarzade13 to numerically study the behavior of tunnels subjected to reverse faults, with further validation through centrifuge testing. The Discrete Element Method (DEM)14,15,16 has also been applied by Xia et al.17 to simulate fault slip and the effect of induced seismic waves on tunnel stability. In addition, Meng et al.18 developed training datasets using the DEM and applied machine learning to predict changes in normal stress, shear stress, and Coulomb failure stress along faults due to tunnel excavation. Furthermore, Li et al.19 used the Material Point Method (MPM) to assess the risks associated with tunnel excavation, highlighting the significant impact of geometric parameters on fault stability, such as the inclination of the fault relative to the tunnel axis. Despite these previous numerical and analytical studies, a direct and practical formulation for assessing fault stability during tunnel construction based on fault and rock mass conditions has not yet been addressed.

In this study, the fault zone near the tunnel is simulated using the Finite Volume Method (FVM) with discontinuities in FLAC3D software20. A large parametric study is conducted that includes important parameters such as the rock mass and mechanical properties of the fault, the depth of the tunnel, the angle of the fault, the size of the tunnel, the distance between the fault and the tunnel and the initial stress state of the surrounding rock. The parametric study is extended to include an additional important aspect, which is the spatial variability of mechanical properties. A probabilistic approach21,22 is employed to examine the influence of the variability in mechanical properties, such as the rock mass modulus and fault friction coefficient, on fault stability. Additionally, a dimensionless metric parameter is developed to estimate the factor of safety of the fault, incorporating the various parameters examined in the parametric study. Finally, the prediction ability of the proposed dimensionless number for a real case study is investigated.

The article is divided into four main sections. Section "Presentation of the 3D model of the tunnel and fault" describes the tunnel and fault model developed in FLAC3D. Section "Parametric study" presents a parametric study of various parameters, including tunnel depth, fault angle, tunnel size, distance between the fault and the tunnel, and the initial stress state. It also outlines the steps to construct the dimensionless number. Section "Non-dimensional number vs. factor of safety" discusses the development of the relationship between the dimensionless number and the factor of safety, considering the effect of the deconfinement rate, as well as the sliding area corresponding to different safety factor values. Finally, Section "Case study of fault slipping after tunnel excavation" presents the validation of the proposed safety approach against a real case study of fault-slip-induced failure after tunnel excavation.

Presentation of the 3D model of the tunnel and fault

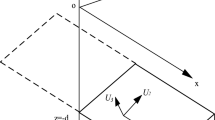

The tunnel-fault numerical model has been developed in FLAC3D, as illustrated in Fig. 1. A single zone is used in the out-of-plane direction (Y-direction) with fixed displacement in that direction, resulting in a plane strain condition. The boundary condition applied is a zero velocity in the normal direction at the lateral and bottom boundaries. The model incorporates a circular tunnel of radius \(R\) = 8 m excavated in an isotropic linear elastic rock mass, with a discontinuity plane. The Poisson’s ratio and the bulk density of the rock mass are held constant at 0.25 and 2700 \({\hbox {kg/m}}^{3}\), respectively. In this study, the distance affected by tunnel excavation, expressed in terms of the tunnel radius \(R\), is estimated to be approximately \(2.5R\) when considering the shear criterion \(\tau = \frac{\tau _{\text {xz}}^{max}}{100}\), where \(\tau _{\text {xz}}^{max}\) is the maximum shear stress on the intrados of the tunnel. Therefore, the model width in Fig. 1 was chosen to be 10 R to satisfy the previous criterion and eliminate any boundary effect. The constitutive model of the fault (Fig. 1) is governed by a linear Coulomb shear-strength criterion, which limits the shear force acting at an interface node. The normal \(K_n\) and shear \(K_s\) stiffness of the discontinuity are set to match the stiffness of the rock mass (\(K_n = 2 K_s = 2 \, \text {GPa/m}\) following Bandis et al.23 and Hungr and Coates24, assuming a Young’s modulus for the rock mass of a few GPa) to avoid introducing heterogeneity in the initial stress state within the rock mass, as demonstrated by the calculations in Section "Influence of rock mass and fault stiffness parameters E and Ks". If the criterion is met (i.e., \(\vert F_s \vert \ge F_{\text {smax}}\)), sliding is assumed to occur, with the shear force limited to \(\vert F_s \vert = F_{\text {smax}}\), while maintaining its original direction. The shear strength of the discontinuity is assumed to have no cohesion or tensile strength and a friction angle \(\varphi\). During sliding, dilatancy \(\psi\) can cause an increase in effective normal stress on the joint \(\sigma _n\)25. Following Heuze26, FLAC3D can consider a correction for the normal stress depending on the dilatancy of the joint as follows:

where \(\vert F_s \vert _o\) is the magnitude of shear force before the correction is applied and \(A\) is the area associated with the interface node. In this study, we adopt a more conservative safety approach and the prior increase in the normal stress is not included by setting \(\psi\) to zero. However, the effect of the joint properties, including dilatancy, on the failure friction criterion will be considered later in Section "Non-dimensional number vs. factor of safety". Finally, the simulations are carried out in two phases: an initialization phase for the geostatic stresses, followed by a total excavation phase (deconfinement ratio \(\lambda = 1\)) of the tunnel, considering the worst-case scenario. The simulations were performed under quasi-static conditions, where inertial effects are neglected.

A comprehensive parametric study has been conducted, varying the parameters listed in Table 1: the inclination angle of the discontinuity \(\alpha\), the friction angle \(\varphi\) of the discontinuity, the initial stress state in the rock mass controlled by two parameters (H, \(K_0\)), Young’s modulus E and the normalized distance between the discontinuity and the tunnel d/R.

Evolution of the shear stress and normal stress on the fault and factor of safety

The evolution of the normal and the shear stresses along a gently inclined discontinuity \(\alpha = 13.5^\circ\) after tunnel excavation is presented in Figs. 2 and 3 for an initial isotropic stress state \(K_0 = 1\), and \(\frac{d}{R} = 1\). The result of the evolution of the interface shear stress after tunnel excavation shows that the projection of stresses onto a prescribed direction (the direction of the discontinuity), which is not a principal direction after excavation, reveals significant shear stresses. This increase in shear stress is accompanied by a decrease in normal stress, as shown in Fig. 3. To quantify these evolutions, two complementary approaches are used. The first approach involves performing numerical simulations assuming perfect adhesion of the discontinuity and then extracting the maximum ratio of shear stress to normal stress along the discontinuity \(\left( \frac{\tau }{\sigma _n} \right) _{\text {max}}\). The safety factor FS can then be derived considering the Coulomb friction criterion as follows:

The second approach applies Coulomb failure criterion to the discontinuity, and the region where the criterion is met is identified.

Parametric study

The influence of each parameter listed in Table 1 is discussed successively in the following sections. The metric function \(\pi\) for each parameter is derived to understand the evolution function for each parameter as a function of the safety factor and then the results are combined into a single dimensionless parameter \(\pi (K_0,\alpha ,H,d,R,E)\) in Section "Non-dimensional number vs. factor of safety" against all the numerical results (including all cross cases). The dimensionless parameter \(\pi\) is established to result in lower FS values for higher \(\pi\) values. The parametric study using the first approach involves 5 parameters, each with three values, resulting in \(3^5 = 243\) simulations. The second approach considers 6 parameters, leading to \(3^6 = 729\) simulations and is used only to match the different values of the factor of safety and the corresponding slipping area.

Influence of rock mass and fault stiffness parameters E and \(K_s\)

A significant relative difference in the stiffness parameters between the fault and the surrounding rock mass can lead to alterations in the initial stability of the fault. Figure 4 illustrates that, within the studied range of Young’s modulus values, there is only a slight difference in the initial factor of safety (before excavation). However, a substantial difference in deformability between the fault and the rock mass (Fig. 4 right) can considerably impact both the initial and final factors of safety. These results confirm that the existence of a weak plane near a tunnel can modify the stress state around the tunnel even before excavation.

After the excavation phase in Fig. 4 (left), the safety factor becomes independent of the Young’s modulus of the rock mass, where the safety factor of the discontinuity remains identical across all three calculation cases. Therefore, the influence of the elastic rock mass Young’s modulus is negligible if the fault does not initially act as a weak plane, and the dependency of the coefficient \(\pi\) on the Young’s modulus can be expressed as follows:

Left: influence of Young’s modulus on the safety factor with \(K_0 = 1.5\), \(K_n = 2\) GPa/m \(\frac{d}{R} = 1,\) \(H = 300\, \text{m},\) \(\alpha = 40^\circ\), \(\varphi = 30^\circ\). Right: influence of the discontinuity stiffness parameters with \(K_0 = 1.5\), \(E = 2\times 10^9\) Pa, \(\frac{d}{R} = 1,\) \(H = 300\) m, \(\alpha = 30^\circ\), \(\varphi = 30^\circ\).

Influence of tunnel depth H

The Kirsch’s solution27 for the closed-form stress state after the total excavation of a circular tunnel in Fig. 5 (deconfinement ratio = 1) in an anisotropic homogeneous stress state can be expressed in polar coordinates in terms of angle \(\theta\) and distance \(r\) as follows:

where \(\sigma _r\) is the radial stress, \(\sigma _\theta\) is the orthoradial stress, and \(\tau _{r\theta }\) is the shear stress in the polar coordinates around a tunnel. Based on Eq. (4), the tunnel vertical stress \(\sigma _0\) in a homogeneous stress field should have a transparent effect on the safety factor of the discontinuity, as any increase in fault normal stress due to an increase in \(\sigma _0\) is accompanied by an equivalent increase in shear stress. However, this is not the case in a non-homogeneous geostatic stress field. Simulations were performed with values of tunnel depths of 100, 200, 300, 400, 500 and 600 m. The safety factors obtained increase slightly as the depth increases (Fig. 6). This is due to the heterogeneity of the initial stress state along the discontinuity, induced by the application of gravity. In other words, at greater depths, the initial stress state is nearly uniform at every point along the discontinuity, whereas this is not the case at shallow depths and/or for large values of the fault angle \(\alpha\). The following function represents the observed evolution of the coefficient \(\pi\) in Fig. 6 as a function of tunnel depth and fault normalized distance :

This function accounts for an increase in the metric function \(\pi\) as the tunnel depth decreases, which indicates a decrease in the factor of safety. It is important to note that the effect of the depth of the tunnel in this study does not include any inertial effects (such as the release of stored energy), which could occur after the maximum allowable shear stress is reached on the fault. These effects become significant as the depth of the tunnel increases, potentially leading to phenomena such as rock bursts. The latter effect is beyond the scope of this article.

Effect of the initial stress state \(K_0\)

The initial stress state plays a significant role in the stability of the fault both before and after the excavation of the tunnel. As shown in Fig. 7, away from the tunnel zone of influence, which represents the initial shear stress on the fault near the tunnel, the shear stress is zero when \(K_0 = 1\) and identical, but with the opposite sign when \(K_0\) ranges from 0.5 to 1.5. As for the initial vertical stress a slight difference can be noticed between the different cases. After the excavation (Fig. 7), for an inclined discontinuity and if \(K_0 = 0.5\), the critical section is located to the left in the negative \(x\)-direction (where \(x=0\) at the center of the tunnel) as the shear component increases significantly. However, if \(K_0 = 1.5\) the critical section is located in the positive \(X\)-direction. For the case of \(K_0 = 1\), two critical sections are defined in both the positive and negative directions of the \(X\)-direction.

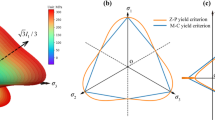

For the different values of \(K_0\) = 0.5, 1, and 1.5, the following safety factor values are obtained for a discontinuity friction angle of \(\varphi = 30^\circ\) in Fig. 7: 1.48, 2.88, and 2.15, respectively. The results propose that the anisotropy of the stress state reduces the safety factor of the discontinuity (whether \(K_0\) is greater or less than 1). The case with \(K_0 < 1\) is more critical than the case where \(K_0 > 1\) . To model this asymmetry compared to the isotropic case, the dependency of function \(\pi\) on \(K_0\) can be expressed as follows:

where the parameters \(m\) and \(n\) will be calibrated later in Section "Non-dimensional number vs. factor of safety" against all the parameters involved in this study. The effectiveness of the proposed equation in capturing the asymmetric behavior of the factor of safety around \(K_0 = 1\) is demonstrated in Fig. 8. The dimensionless parameter \(\pi\) is established to result in lower FS values for higher \(\pi\) values. Therefore, the relationship between the FS and \(K_0\) can be expressed as follows:

Influence of fault angle \(\alpha\)

In this study, we varied the angle \(\alpha\) while keeping the distance d constant between the tunnel crown and the discontinuity. Three angles were considered: \(13.5^\circ\), \(30^\circ\), and \(40^\circ\), as shown in Fig. 9, for the case of \(H = 500 \, \text {m},\) \(E = 2 \times 10^9 \, \text {Pa}\), \(K_0 = 0.5\), and \(d/R = 1\). For a discontinuity with a friction angle \(\varphi = 30^\circ\), the computed safety factor (\(FS\)) values are 1.48, 0.93, and 0.75 for \(\alpha = 13.5^\circ\), \(30^\circ\), and \(40^\circ\), respectively. The results in Fig. 9 demonstrate that the shear stresses along the discontinuity increase as the angle \(\alpha\) increases, leading to a decrease in the factor of safety as \(\alpha\) increases. Therefore, the evolution of \(\pi\) as a function of \(\alpha\) can be written as follows:

where a and \(b\) are the function evolution parameters to be calibrated in Section "Non-dimensional number vs. factor of safety".

Influence of the normalized fault distance from the tunnel \(\frac{d}{R}\)

The ratio \(\frac{d}{R}\) is a key parameter in the evolution of stresses along the discontinuity. The closer the discontinuity to the excavation, the more it is stressed, as illustrated in Fig. 10 for \(\frac{d}{R}\) ratios of 1.5, 1, and 0.5, respectively. The safety factor values obtained are 1.2, 0.93, and 0.6 for \(\frac{d}{R}\) ratios of 1.5, 1, and 0.5, respectively, with a fault friction angle \(\varphi\) of \(30^{\circ }\). The factor of safety decreases as the fault is approached to the tunnel due to the increase in shear stress along the discontinuity, as shown in Fig. 10. Finally, the following function can be considered to represent the evolution of the safety factor \(\pi\) with respect to the normalized distance \(d/R\):

where f and \(c\) are the function evolution parameters to be calibrated in Section "Non-dimensional number vs. factor of safety". Equation (9) shows that when the fault locates far from the tunnel (i.e., at a distance \(\frac{d}{R} > 2\)), the fault stability is mostly determined by the initial configuration parameters (without the presence of the tunnel) \(K_0\), H, and \(\alpha\). As a reference, Fig. 11 compares the two calculation approaches used in this study: (a) perfect adhesion along the discontinuity with a posterior calculation of the area that would have reached the criterion, and (b) Coulomb friction directly applied in the model on the discontinuity. This figure shows that both approaches are consistent, as the location and slipping length that reach the slipping criterion in (a) correspond to the same location and distance where \(FS < 1.\)

Effect of spatial variability of mechanical properties

Considering the inherent complexity of in-situ conditions, the spatial variability of mechanical properties is regarded as an important aspect to consider in fault stability analysis. This section investigates spatial variability using a random field (RF) probabilistic approach28, with normal distributions applied to model the rock mass Young’s modulus and the fault friction angle in two different simulations.

The Young’s modulus of the rock mass was modeled as a normal random variable in Fig. 12 with a mean value of \(2 \times 10^9 \, \text {Pa}\) and a standard deviation of \(8 \times 10^8 \, \text {Pa}\) following28, while the fault friction coefficient in Fig. 13 was assigned a mean of \(30^\circ\) and a standard deviation of \(5^\circ\). The mean and standard deviation values of the friction angle variability along the discontinuity are consistent with the values provided by29 for different types of discontinuities in terms of rock mass type and infilling materials. Simulations were conducted for the case of \(K_0 = 1.5\), \(K_n = 2 \, \text {GPa/m}\), \(\frac{d}{R} = 1\), and \(\alpha = 30^\circ\). For the probabilistic simulation of the Young’s modulus, the fault friction angle is set as constant, with a value of \(30^{\circ }\). To ensure statistical reliability, 1000 simulations were conducted. The results of each case showed convergence of the mean value of the factor of safety after approximately 600 simulations as shown in Fig. 13.

In the case of the RF for Young’s modulus, the results indicate a higher factor of safety compared to the deterministic approach. The mean probabilistic factor of safety is \({\bar{FS}}_{\text {probabilistic}} = 1.54\), while the deterministic factor of safety is \(FS_{\text {deterministic}} = 1.46\). Across 1000 simulations, no slipping conditions were observed, suggesting that slipping is unlikely to occur under these conditions.

For the case of the RF for the friction angle \(\varphi\), the results indicate a lower factor of safety compared to the deterministic approach, with a mean probabilistic FS of \({\bar{FS}}_{\text {probabilistic}} = 1.39\) versus \(FS_{\text {deterministic}} = 1.46\). The histogram in Fig. 14 illustrates the distribution of the simulations based on the FS. Overall, the distribution is skewed towards lower FS values. A notable portion of the simulations falls into the failure zone (\(FS\) \(\le\) 1.0), with approximately 120 occurrences, representing scenarios where failure is likely. The most frequent range, between 1.3 and 1.5, includes about 180 simulations, suggesting that the majority of scenarios exhibit marginal safety. Beyond this range, the frequency of simulations decreases steadily as the FS increases, indicating fewer cases with substantial safety margins. In the upper end, very few simulations have an FS greater than 2.2, highlighting the rarity of scenarios with extreme safety levels. The analysis reveals that a factor of safety around 1.5 does not guarantee stability when considering the spatial variability of the friction angle along the fault.

Finally, future studies should include a more comprehensive probabilistic analysis to evaluate the impact of variability across all examined parameters, their interactions, and statistical characteristics such as correlation length and distribution law.

Left: Two simulations with a normal distribution of the fault friction angle (\(x=0\) at the center of the tunnel) with a mean = \(30^\circ\) and a standard deviation = \(5^\circ\). Right: convergence of the mean value of the factor of safety with number of stochastic numerical simulation of the fault friction angle.

Non-dimensional number vs. factor of safety

Considering the parameter-by-parameter study conducted in the previous section, the dimensionless parameter \(\pi\) can finally be written as a function of all the studied parameters: \(\pi (K_0, \alpha , H, d, R, E)\). It is important to note that the dimensionless parameter \(\pi\) is constructed to result in a lower factor of safety for higher values of \(\pi\). The different evolution parameters as well as the relative weight of each function are calibrated to provide the best fit for the factor of safety \(FS\) against the 243 simulations performed, as shown in Fig. 15. Excellent correlation coefficients are obtained (\(> 0.95\)) confirming the effectiveness of the proposed evolution functions. Finally, the dimensionless parameter \(\pi\) can be written as a function of all the involved parameters as follows:

The safety factor \(FS\) can be expressed as a function of the dimensionless parameter \(\pi\) and fault friction angle \(\varphi\) as follows:

Equation (11) can be applied to obtain the factor of safety with respect to fault stability near a tunnel. Alternatively, Fig. 15 can be directly used to obtain the fault factor of safety depending on the fault friction coefficient. In particular, Eq. 11, as confirmed by the simulations, highlights that the following two cases (within the framework of the considered modeling assumptions) result in safety factors less than 1 along the discontinuity:

-

\(\varphi = 20^\circ\), \(d_{\text {min}} < 0.45R\) (\(d/R < 0.5\) and \(\alpha > 13.5^\circ\)), \(0.5< K_0 < 1.5\);

-

\(\varphi = 30^\circ\), \(d_{\text {min}} < 0.7R\) (\(d/R < 1\) and \(\alpha > 30^\circ\)), \(K_0 < 0.8\).

where \(d_{\text {min}}\) represents the minimum distance between a fault and a tunnel. Estimation of the friction angle of the discontinuity \(\varphi\) depends on the type of rock mass, such as dolomite, granite, etc., and the presence of infill material (gouge), thermal and hydraulic conditions in the discontinuity29,30,31.

The effect of the deconfinement rate, \(\lambda\), on the factor of safety (FS) is critical to accurately capture the progressive deconfinement process. To investigate this, numerical simulations were performed in FLAC3D under plane strain conditions, covering a wide range of deconfinement rate values \(\lambda \in [0, 1]\). Furthermore, simulations were systematically conducted for varying values of \(K_0\) to account for the intrinsic variations in stress redistribution mechanisms induced by tunnel excavation under different \(K_0\) conditions (see Eq. 4). A scaling factor \(S(\lambda )\) was derived in Fig. 16 to transform the reference FS, given by Eq. (11) for \(\lambda = 1\), to any arbitrary deconfinement level.

Also, Eq. (11) can also be written as a function of the residual friction angle of the mechanical properties of the interface \(\varphi _r\), the compressive strength of the joint wall JCS and the joint roughness coefficient JRC (including scale effects on the previous parameters32) as follows:

Also, at large depths, faults can be affected by water pressure by groundwater level. The latter effect can also be incorporated in Eq. (12) as follows:

where u is the pore pressure at the interface level, assuming that the ratio \(\frac{u}{{\sigma _n}}\) remains constant before and after the excavation. These methods offer effective tools to assess the safety margin along faults near tunnel excavation.

Finally, it would be interesting to explore the relationship between the discontinuity length or area that meets the criterion and the associated safety coefficients. Figure 17 compares the safety factor calculated under the assumption of perfect adhesion of the discontinuity, with the length of the discontinuity that reaches the Coulomb criterion. In general, the results show that as the safety factor decreases, the sliding distance increases, indicating a higher stability risk along the sides of the excavated tunnels. However, it is important to note that the sliding area along the discontinuity is not directly proportional to the factor of safety (Fig. 18), since in some cases (when \(K_0 = 1\) with a low friction angle \(\varphi\)), the slipping criterion can be reached at different locations, as shown previously in Fig. 7, leading to a greater slipping area for the same factor of safety compared to other cases with an initial anisotropic stress state. Future studies could focus on developing a reliable relationship between the slipping area (or slip displacement) and the dimensionless parameter \(\pi\). Such a relationship would offer another valuable tool for assessing the potential risk of rockbursts, as the potential energy released from slip along a fault is primarily dependent on the faults slipping area and slip displacement33.

Discussion

The orientation of the fault in this study, represented by the angle \(\alpha\) and ranging from \(0^\circ\) to \(45^\circ\), accounts for all possible fault orientations. For example, the safety factor for a fault with an angle \(\alpha\) passing above the tunnel is equivalent to that of a fault with an angle \(360^\circ - \alpha\) passing below the tunnel as shown in Fig. 19. This equivalence is due to the symmetry of the shear stress distribution around a circular-shaped tunnel after excavation.

Figure 20 shows the evolution of shear and normal stresses, as well as the safety factor for different discontinuities with different locations in relation to the tunnel but with the same angle \(\alpha\). The results show the same value for the FS when the fault is located above the tunnel; however, a slight increase in the FS is observed when the fault is located below the tunnel due to a slight increase in normal stress.

Case study of fault slipping after tunnel excavation

This section presents a real-world case study, illustrated in Fig. 21, involving a fault-slip-induced failure following the excavation of a semi-circular tunnel with a radius R of 9 m and H=700 m. The surrounding rock mass in the fault area primarily consists of dolomitic rock. The compressive strength of these dolomites ranges from 53 MPa to 74 MPa, with a density of 27 \({\hbox {kN/m}}^{3}\). Other key geomechanical properties include an uniaxial compressive strength of 74 MPa, Young’s modulus of 51.7 GPa, Poisson’s ratio of 0.2, and a tensile strength of 6.9 MPa. The fault is a traversing fault characterized by an extension beyond the tunnel diameter. Its orientation is almost parallel to the tunnel excavation, making it critical for stability. It also features a significant opening with fillings ranging from a few millimeters to 5 cm, potentially promoting sliding along the fault plane. After the tunnel excavation, the volume of the collapsed rock is estimated to be approximately 200 \({\textrm{m}}^{3}\), extending over a length of about 15 m. The support system includes rock bolts ( 8 m long, spaced at 2 m \(\times\) 1 m) with a Young’s modulus of 210,000 MPa, tensile strength of 0.400 MN, grout deformability of 17,158 MPa/m, and a grout/ground shear strength of 1.5 MPa. Three shotcrete layers (10 cm synthetic fiber, 10 cm steel fiber, and 5 cm non-reinforced finishing) are applied, with the structural layers simplified to 20 cm having a compressive strength of 1 MPa and a deformation modulus of 7,000 MPa. The deconfinement rate during support installation is estimated to be \(\lambda = 0.87.\)

The friction angle of the fault is estimated to be \(\varphi\) of \(32^{\circ }\), based on the values of JCS (=2) and JRC (=55 MPa). The initial stress state has been estimated from various hydraulic fracturing tests conducted around the collapsed area, with the upper and bottom levels of the lateral earth pressure coefficient, \(K_0\), ranging from 0.65 to 1.24. Finally, the fault and tunnel characteristics required to calculate the dimensionless number \(\pi (K_0, \alpha , H, d, R, E)\) are as follows:

where \(H_{\text {eq}}\) and \(\sigma _v\) are the equivalent depth and vertical stress at the crown of the tunnel, respectively. In comparison with the findings of the current study, the position of the collapses shown in Fig. 21 corresponds closely to the critical sections identified in Figs. 7 and 9. Second, for both the upper and lower levels of \(K_0\), the factor of safety in Fig. 22 is shown to be less than 1.5, indicating an unstable condition for the fault (see Section "Effect of spatial variability of mechanical properties"). Additionally, the current case represents a deep tunnel where the slipping of the fault will induce a rockburst effect, generating collapses in the plastified area around the tunnel.

Conclusions

This study presents a comprehensive evaluation of fault stability near circular tunnels, focusing on key parameters that impact stability, such as fault angle, tunnel size, depth, fault-to-tunnel distance, fault-tunnel mechanical properties, and initial stress state. A detailed numerical parametric study was conducted, incorporating these parameters to assess the fault factor of safety against slipping. Numerical simulations were conducted under conservative assumptions, with a deconfinement rate of 1 and no increase in normal stress due to fault dilatancy.

Among these parameters, initial stress state, the ratio of fault distance to tunnel size, and the angle of inclination of the fault emerged as the most influential factors. In addition, the location of the critical section, and thus the slipping distance along the fault plane and the corresponding safety factor, are highly dependent on the initial stress state of the rock mass.

In addition, the study emphasized the potentially significant impact of the difference in relative deformability parameters between the rock mass and the fault on both the initial and final factor of safety of the fault. However, in the conducted parametric study, the fault stiffness parameters used did not represent a weak plane prior to the tunnel excavation, and as a result, the safety factor after excavation was found to be independent of the rock mass Young’s modulus. The effect of tunnel depth on the factor of safety was shown to be less significant, particularly in the case of deep tunnels. In addition, the probabilistic approach, which accounts for the spatial variability of the rock mass Young’s modulus, yielded a higher factor of safety compared to the deterministic method. Conversely, the spatial variability of the fault friction angle yielded a lower factor of safety compared to the deterministic method. However, a more comprehensive probabilistic analysis is necessary to thoroughly evaluate parameter variability and their interactions. The results of the probabilistic approach highlight that a factor of safety of 1 may not ensure fault stability when considering the potential effects of spatial variability of the fault friction angle.

Depending on the understanding of the influence of each parameter individually, an evolution function was defined for each parameter in relation to the safety factor. Afterwards, a dimensionless parameter \(\pi\) was developed reflecting the influence and the weigh of each parameter involved in the parametric study. The dimensionless parameter \(\pi\) is calibrated based on the results of the numerical parametric study showing excellent correlation coefficients \(= 0.96\). Also, the deconfinement rate is also included to estimate the factor of safety at different construction stages. In addition, the developed safety approach is extended to incorporate more advanced shear criteria, such as Barton’s model, along with the consideration of pore pressure, which is critical for deep tunnel stability. The dimensionless parameter developed in this study \(\pi\) offers a valuable tool for an initial estimation of fault stability by consolidating multiple influencing factors into a simplified metric.

Furthermore, the proposed approach using the dimensionless number was validated against a real case study of fault-slip-induced failure following tunnel excavation. The results demonstrated that the dimensionless number accurately predicted both the factor of safety and the location of fault slipping, confirming the method reliability and applicability in practical scenarios. Although effective as a first-step assessment, this quasi-static approach should be complemented by advanced dynamic analyses in cases where the depth and potential rockbrust influences are significant.

As a perspective of this work, a more extended study could be conducted, incorporating additional parameters to the proposed approach such as an elastoplastic constitutive model for the rock mass, tunnel shape, discontinuity properties and dilatancy angle, extended probabilistic approach, and the potential dynamic effects of rockburst on the stability of the fault-tunnel zone.

Data availibility

Some or all data, models, or codes that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- \(K_0\) :

-

Coefficient of lateral earth pressure

- \(\alpha\) :

-

Inclination angle of the fault

- \(\varphi\) :

-

Friction angle of the fault

- \(FS\) :

-

Factor of safety

- \(JCS\) :

-

Joint wall compressive strength

- \(JRC\) :

-

Joint roughness coefficient

- \(R\) :

-

Radius of the tunnel

- \(H\) :

-

Depth of the tunnel center from the ground surface

- \(d\) :

-

Vertical distance between the fault and the tunnel crown

- \(d_{\text {min}}\) :

-

Minimum distance between the fault and the tunnel

- \(\left( \frac{\tau }{\sigma _n} \right) _{\text {max}}\) :

-

Maximum ratio of the shear and normal stress along the fault

- \(E\) :

-

Young’s modulus of the rock material

- \(\sigma _n\) :

-

Fault normal stress

- \(\tau\) :

-

Fault shear stress

- \(\pi\) :

-

Dimensionless parameter for fault stability

- \(u\) :

-

Fault pore pressure

- \(\rho\) :

-

Density of the rock mass

- \(K_n\) :

-

Normal stiffness of the discontinuity

- \(K_s\) :

-

Shear stiffness of the discontinuity

- \(F_s\) :

-

Shear force

- \(F_{\text {smax}}\) :

-

Maximum allowable shear force

- \(\psi\) :

-

Dilatancy angle

- \(A\) :

-

Area associated with the interface node

- \(\sigma _0\) :

-

Initial vertical stress

- \(\sigma _r\) :

-

Radial stress

- \(\sigma _\theta\) :

-

Orthoradial stress

- \(\tau _{r\theta }\) :

-

Shear stress in polar coordinates

- \(\theta\) :

-

Angle in polar coordinates

- \(r\) :

-

Radial distance from the tunnel center

- \(\lambda\) :

-

Tunnel deconfinement rate

- \(\varphi _r\) :

-

Residual friction angle

- \(\text {COV}\) :

-

Coefficient of variation

- \(\text {RF}\) :

-

Random field

- \(S(\lambda )\) :

-

Scaling factor to account for the deconfinement rate in fault factor of safety

References

Asakura, T. & Sato, Y. Damage to mountain tunnels in hazard area. Soils Found. 36, 301–310 (1996).

Dalgıç, S. Tunneling in fault zones, Tuzla tunnel, Turkey. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 18, 453–465 (2003).

Zuo, Q., Li, X., Li, P., Deng, M. & Adoko, A. C. Surrounding rock instability mechanism for fault-crossing tunnels in water-rich soft rock. Bull. Eng. Geol. Env. 83, 1–15 (2024).

Yang, H., Wang, M., Yu, L. & Zhang, X. Analytical and numerical analysis on the mechanical response and damage characteristics of tunnels subjected to multiple normal faulting. Comput. Geotech. 169, 106254 (2024).

Snelling, P. E., Godin, L. & McKinnon, S. D. The role of geologic structure and stress in triggering remote seismicity in Creighton mine, Sudbury, Canada. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 58, 166–179 (2013).

Rinaldi, A. P. & Urpi, L. Fault reactivation induced by tunneling activity in clay material: Hints from numerical modeling. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 102, 103453 (2020).

Zhang, X., Yu, L., Wang, M. & Yang, H. Mechanical response and failure characteristics of tunnels subjected to reverse faulting with nonuniform displacement: Theoretical and numerical investigation. Eng. Fail. Anal. 156, 107809 (2024).

Blake, W. & Hedley, D. G. Rockbursts: Case studies from North American hard-rock mines. (SME, 2003).

Gao, F., Kang, H. & Li, J. Numerical simulation of fault-slip rockbursts using the distinct element method. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 110, 103805 (2021).

Einstein, H. H. & Schwartz, C. W. Simplified analysis for tunnel supports. J. Geotech. Eng. Div. 105, 499–518 (1979).

Wang, H., Utili, S., Jiang, M. & He, P. Analytical solutions for tunnels of elliptical cross-section in rheological rock accounting for sequential excavation. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 48, 1997–2029 (2015).

Vitali, O. P., Celestino, T. B. & Bobet, A. Analytical solution for a deep circular tunnel in anisotropic ground and anisotropic geostatic stresses. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 53, 3859–3884 (2020).

Sabagh, M. & Ghalandarzadeh, A. Numerical modelings of continuous shallow tunnels subject to reverse faulting and its verification through a centrifuge. Comput. Geotech. 128, 103813 (2020).

Cundall, P. A. & Strack, O. D. A discrete numerical model for granular assemblies. Geotechnique 29, 47–65 (1979).

Mohamed, T., Duriez, J., Veylon, G., Peyras, L. & Soulat, P. A 3D-dem model for tropical residual soils under monotonic and cyclic loadings. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 149, 04023094 (2023).

Li, B., Jiang, Y., Tanabashi, Y. & Yamashita, Y. Behavior of large scale underground cavern located in jointed rock masses evaluated by using distinct element method. Soils Found. 50, 609–621 (2010).

Xia, C. et al. Seismic response of mountain tunnel induced by fault slip. Sci. Rep. 14, 17768 (2024).

Meng, W., Xu, N., Zhao, Z. & Wu, W. Excavation-induced fault instability: A machine learning perspective. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 57(7), 5251–5265 (2024).

Li, Z., Huang, H., Zhou, M. & Zhang, D. Failure responses of rock tunnel faces during excavation through the fault-fracture zone. Undergr. Space 10, 166–181 (2023).

Itasca. Pfc - particle flow code, ver. 6.0. Itasca Consulting Group, Inc. (2018).

Camós, C., Špačková, O., Straub, D. & Molins, C. Probabilistic approach to assessing and monitoring settlements caused by tunneling. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 51, 313–325 (2016).

Zhou, X.-P., Huang, X.-C., Liu, P.-F. & Li, T.-F. A probabilistic method to analyze collapse failure of shallow rectangular tunnels. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 82, 9–19 (2018).

Bandis, S., Lumsden, A. & Barton, N. Fundamentals of rock joint deformation Vol. 20, 249–268 (Elsevier, 1983).

Hungr, O. & Coates, D. Deformability of joints and its relation to rock foundation settlements. Can. Geotech. J. 15, 239–249 (1978).

Thirukumaran, S. & Indraratna, B. A review of shear strength models for rock joints subjected to constant normal stiffness. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 8, 405–414 (2016).

Heuze, F. E. Dilatant effects of rock joints, ISRM–4CONGRESS (ISRM, 1979).

Kirsch, E. G. Die theorie der elastizit t und die bed rfnisse der festigkeitslehre. Zeitshrift des Vereines deutscher Ingenieure 42, 797–807 (1898).

Song, K.-I., Cho, G.-C. & Lee, S.-W. Effects of spatially variable weathered rock properties on tunnel behavior. Probab. Eng. Mech. 26, 413–426 (2011).

Muralha, J. & Pinto Da Cunha, A. About LNEC experience on scale effects in the mechanical behaviour of joints, 131–148 (1990).

Faulkner, D. R., Sanchez-Roa, C., Boulton, C. & Den Hartog, S. Pore fluid pressure development in compacting fault gouge in theory, experiments, and nature. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 123, 226–241 (2018).

Kim, T. & Jeon, S. Experimental study on shear behavior of a rock discontinuity under various thermal, hydraulic and mechanical conditions. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 52, 2207–2226 (2019).

Bandis, S., Lumsden, A. & Barton, N. Experimental studies of scale effects on the shear behaviour of rock joints Vol. 18, 1–21 (Elsevier, London, 1981).

Richards, P. G. & Aki, K. Quantitative seismology: Theory and methods Vol. 859 (Freeman, San Francisco, 1980).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Tarek Mohamed: Writing-original draft, Software, Investigation, Conceptualization. Amro Nasr: Writing-review and editing..

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mohamed, T., Nasr, A. Evaluating fault stability near tunnels: a numerical parametric study and a dimensionless safety approach. Sci Rep 15, 11483 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-94904-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-94904-3