Abstract

The freeze-thaw damage of cementitious coarse grained fillings (CCGFs) significantly affects the firmness, stability, and durability of high-speed railway subgrades. It is favorable to employ geopolymer binders to improve the engineering performance of coarse grained fillings (CGFs), further ensure the safety of high-speed railway subgrades in cold regions due to their excellent mechanical and environmental-friendly performances. This study conducted a series of freeze-thaw and mechanical tests on geopolymer stabilized coarse grained fillings (GSCGFs). The influence of gradation, compaction degree, and freeze-thaw cycles on the integrity, strength, and stiffness of GSCGFs was investigated. The evolution law of their freeze-thaw damage was discussed quantitatively based on an improved damage factor. The results show that the mass loss rate of Group B GSCGFs with a fine-grained particle content of less than 15% was lower than that of Group A GSCGFs with a fine particle content between 15% and 30% overall. When other conditions remain unchanged, the mass loss rate of GSCGFs decreased with the increase of compaction degree but increased nonlinearly with the freeze-thaw cycles. The strength and stiffness of GSCGFs decrease nonlinearly with the freeze-thaw cycles and presented a first fast and then slow-down change trend, their stiffness evolution at different compaction degrees revealed a big difference due to the weakening bite effect and enhancing overhead structure among rock blocks. The strength reduction of Group A GSCGFs was less than that of Group B under the high compaction degree. The stiffness deterioration of Group A GSCGFs was about twice that of Group B. There seemed to be no absolute correlation that the strength of GSCGFs was positively correlated with their stiffness. By building an exponential relationship between the compressive strength of GSCGFs and the freeze-thaw cycles that followed the findings of previous several studies, an improved exponential damage evaluation model was proposed to represent the performance degradation of GSCGFs. The outcomes of this study can provide theoretical support for understanding the physical and mechanical behaviors of GSCGFs and applying them in engineering practices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Coarse grained fillings (CGFs) are characterized by high strength, high stiffness, low compressive deformation, and excellent dynamic stability, making them the preferred material of choice for high-speed railway subgrade1,2,3. However, with the development of global urbanization, the construction of transportation infrastructure is increasingly extending into cold regions4. Although numerous studies pointed out that CGFs were less sensitive to frost heave due to their low water absorption and clay content5,6, different degrees of subgrade diseases were still found in many high-speed railway subgrades in cold regions, such as Harbin-Dalian High-Speed Railway and Danda Railway7,8. Especially due to the effects of freeze-thaw cycles or southern and northern slopes, problems such as frost heave, thaw settlement, cracking, and uneven deformation in high-speed railway subgrades in cold regions are becoming increasingly prominent7,9,10. Further improving the performance of CGFs is of great significance for ensuring the safety of high-speed railway subgrades in cold regions11,12. Some studies indicated that the water absorption of clay particles was the main culprit for causing the frost-heaving damage of subgrade fillings5,13. Hence, one of the most effective ways to improve the frost resistance of subgrade fillings by eliminating the influence of clay particles.

Scholars both domestically and internationally have indicated that cementitious coarse grained fillings (CCGFs) exhibit superior service performance for high-speed railway subgrades in cold regions3,14,15. Research had also revealed that the performance degradation of CCGFs subjected to freeze-thaw cycles was mainly affected by gradation, compaction degree, and freeze-thaw cycles. Among them, the gradation and compaction degree were the primary factors16. These parameters determined the soil skeleton structure and changed the frost damage effect of CCGFs with their changes17,18. Bu and Wang19 and Gao et al.20 reported that the fine particle content had a significant impact on the frost heave effect of argillaceous CCGFs, and its mass proportion should not exceed 5%; Liu et al.21 and She et al.22 found that the uneven spatial distribution of fine particles significant affected the mechanical properties of argillaceous CCGFs subjected to freeze-thaw cycles. The higher the unevenness of fine particles in space, the more remarkable the softening of argillaceous CCGFs; Wang et al.23 and Liu et al.16 showed that the fine-grained content affected the compaction characteristics of argillaceous CCGFs seriously. Different compaction degrees caused different frost heave ratios. The frost heave ratio would reach the maximum value when compacted by the standard compaction energy and achieve the minimum value when insufficient. Regarding the impact of freeze-thaw cycles on CCGFs, studies indicated that the structural characteristics of CCGFs would change after freeze-thaw cycles, developing from an unstable state to a dynamically stable state24,25,26. Peng et al.27 pointed out that the shear strength of CCGFs after freeze-thaw cycles would be lower than before and tended to flatten when the freeze-thaw cycles reached a certain number; Xie et al.10 and Yang and Zhang28 found that the cohesion and uniaxial compressive strength of CCGFs decreased with the freeze-thaw cycles, but internal friction angle did not show significant changes; Chang et al.29 found that the static strength and elastic modulus of weakly cemented CGFs had a decreasing and then increasing trend with the freeze-thaw cycles and would reach the minimum value after seven to nine freeze-thaw cycles; several scholars pointed out that the elastic modulus of CCGFs was significantly impacted by the freeze-thaw cycles and their deterioration was particularly prominent after the first few freeze-thaw cycles and tended to a stable state after more than nine freeze-thaw cycles6,30,31. However, these finding primarily reflected more characteristics of weakly cemented CGFs. It is unclear whether the case of strongly cemented CCGFs could follow the same rules.

Regarding the damage evolution of CCGFs, numerous studies explored damage factors to explain their changes in microstructure characteristics and macroscopic physical and mechanical properties32,33,34,35. These studies consistently pointed out that the void ratio and pore size expanded with the freeze-thaw cycles. However, these changes would slow down when the freeze-thaw cycle reached a certain number of freeze-thaw cycles36. In terms of the damage factors defined by indicators such as porosity and defect area, Li et al.37 proposed a new microscopic damage parameter and freeze-thaw damage constitutive model through mercury intrusion porosimetry (MIP) and differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) tests; Liu et al.38 investigated the pore structure characteristics of CGFs after different freeze-thaw cycles using nuclear magnetic resonance and pointed out that there was a good fitted exponential relationship between the proportion of pore volume and the relative strength of CGFs. For the damage factors defined by density, elastic modulus, stress, strain, etc., Tong et al.39 established an elastic-plastic damage model for cement soils based on Helmholtz thermodynamic principles and Lemaitre damage equivalence principles; Ling et al.34 studied the performance degradation of CGFs subjected to freeze-thaw cycles through consolidated drainage triaxial tests. They also proposed a stress-strain prediction model inspired by experimental observations that could reflect their residual strength using a continuum damage mechanics framework. Wang et al.40 further proposed a micromechanics-based binary-medium constitutive model combining the breakage mechanics for geomaterials theory and the homogenization method. However, although these studies could provide a valuable reference to the mechanical effect evaluation of weakly cemented CGFs, there was no compelling evidence to date that these models could accurately describe the damage evolution of CCGFs, particularly under repeated freeze-thaw action.

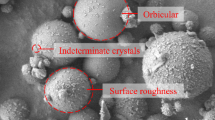

In nature, CCGFs always appear in the form of weak cementation like argillaceous or overhead. Due to their not necessarily ideal gradation, the physical and mechanical performances of natural CCGFs might not meet the requirements of engineering practices. At these moments, necessary improvements shall work for CCGFs. The commonly used stabilizer is lime. However, due to the hexagonal plate-like structure characteristics of products by lime hydration on a microscopic level, strong dry shrinkage cracking would occur. It would be better to choose these stabilizers with more outstanding performances. The geopolymer binder is an inorganic gel with a spatial network structure formed by the depolymerization and geopolymerization of aluminosilicate minerals (usually taking high silicon aluminum solid wastes as raw materials) in an alkaline environment41,42. It has the advantages of early strength, rapid hardening, environmental protection, resource-saving, and the potential to replace cement in the future8,43. Suppose they were used to improve the engineering performances of CGFs, their high strength and durability shall increase the bonding force between soil particles, making them less prone to unexpected deformation under the transmission of upper structures and long-term traffic loads, thereupon then ensuring the safety and stability of engineering construction in cold regions43,44,45. They can also alleviate the shortage of high-quality fillings, thereby assisting the construction technology development of high-speed railways. On the whole, the geopolymer stabilized coarse grained fillings (GSCGFs) are special geo-materials with relatively strong cementation. However, research on GSCGFs subjected to freeze-thaw cycles and other durability conditions has been relatively limited up until now. The valuable reference research for more course references seems to mainly come from concrete materials46,47.

Given the insufficient understanding of the freeze-thaw damage mechanisms, degradation processes, and evolution characteristics of GSCGFs, this study conducted a series of freeze-thaw cycles and mechanical tests on GSCGFs. The influence of gradation, compaction degree, and freeze-thaw cycles on the integrity, strength, and stiffness of GSCGFs were systematically investigated. The evolution law of freeze-thaw damaged GSCGFs was discussed quantitatively based on the damage factor in the final.

Materials and methods

Experimental materials

-

(1)

CGFs

CGFs (as one of the soil rock mixtures) are widely used in railway subgrade engineering. The Standard for Engineering Classification of Soil (GB/T50145-2007)48 defines this geomaterial as fine-grained soil with a coarse grained particle (possessing a size of 0.075 mm ≤ d ≤ 60 mm) content greater than 50%. In other words, it can be regarded as the mixture of rock blocks with high stiffness and the soil matrix with a relatively low strength. Following these cognitions, the remolded CGFs samples in this study were considered to consist of clay with a particle size of 0.075 mm or less, fine sand with a particle size of 0.075–0.25 mm, medium-coarse sand with a particle size of 0.25–0.5 mm, coarse sand with a particle size of 0.5–2.0 mm, and rock blocks with a particle size of 2.0–20.0 mm, rather than collecting the experimental CGFs from the construction site, as shown in Fig. 1. The clay used in the experiment was collected from a construction site in the Jiangpu Campus of Nanjing Tech University. It was dried, crushed, and sieved through a sieve with a hole size of 0.075 mm. The fine sand was taken from a deep foundation pit in the Yangtze River floodplain area of Pukou District, Nanjing. It was gray-brown and had a 1.94 g/cm3 density. Considering that the fine sand contains particles beyond the defined size range, this fine sand was dried and screened before use. The medium-coarse sand was the standard sand for the sand-filling method in railway engineering. It was light yellow and had a density of 1.51 g/cm3. The coarse sand with a 0.5–1.0 mm particle size was the ISO sand for water demand measurement. The coarse sand with a 1.0–2.0 mm particle size and rock blocks were collected from a quarry in Pukou District, Nanjing City. It was gray and hard. The lithology belonged to lightly weathered limestone. Their shape was mainly angular, with a dry density of 2.53 g/cm3 and a water absorption rate of 0.63%.

-

(2)

Geopolymer binder

The geopolymer binder was comprised of metakaolin, sodium silicate, and calcium oxide, as shown in Fig. 2. The metakaolin, a white powder with a fineness of 1250 mesh, was sourced from Henan Hengyuan New Materials Co., Ltd., China. The modulus of sodium silicate was 3.0. The purity of calcium oxide produced by Wuxi Yatai United Chemical Co., Ltd., China was analytically pure with an active mineral content of over 95%. Baesd on prior study by the authors, the mass ratio of metakaolin, sodium silicate, and calcium oxide for preparing geopolymer binders in normal atmospheric temperature was 3.6:1:0.8 49, which chose the component materials from the same source.

Experimental scheme

Based on a comprehensive review of domestic and international literature, this study mainly focused on exploring the effects of gradation, compaction degree, and freeze-thaw cycles on the mechanical properties of GSCGFs and the quantitative characterization of their damage degradation laws. The Code for Design of Railway Earth Structure (TB 10001 − 2016) issued by the National Railway Administration of the People’s Republic of China has given the requirements in coarse-grained and clay contents for different subgrade fillings and suggested Groups A and B CGFs as the ideal fillings in cold regions50. Because the Group A CGF is a well-graded filling with a fine-grained particle content of less than 15%, while the Group B CGF has a fine particle content between 15% and 30% regardless of poor gradation. Considering that the fine-grained particle content and structural characteristics of GSCGFs will significantly impact their physical and mechanical properties, two typical grading curves of GSCGFs that kindly met the requirements of railway subgrade fillings were designed following a continuity equation, as shown in Fig. 3. Then the mass loss rate measurements and mechanical performance tests were conducted after each freeze-thaw cycle, both before and after saturation.

The specific experimental schemes were as follows:

-

(1)

Mass loss rate test

The Technical Specification for Construction of High-speed Railway Earth Structure Engineering (QCR9602-2015) issued by China Railway Corporation51 stipulates that the minimum compaction degree of roadbed foundation should not be less than 85% and a higher compaction degree should be selected for subgrade filling construction with special soils. Hence, the mass loss rate tests were conducted on Groups A and B GSCGF specimens with compaction degrees of 89%, 92%, and 95%. When the curing age reached 24 days, the prepared specimens were first weighted and then placed into the water at a temperature of (20 ± 2)℃ for a four-day saturation. When soaked, the water surface should be higher than 2–3 cm of the upper surface of the specimens. When the curing age reached 28 days, these specimens were taken outside the water, wiped off the surface moisture, and weighed carefully. Then, they were placed in the programmable freeze-thaw cycle chamber to carry out the damage evolution measurement. For the temperature program, this study launched the temperature of freeze-thaw cycles obeying a program from − 30℃ to 20℃ with a cosine variation in 24 h. The selection of the minimum temperature as -30℃ was for two reasons: one was that the GSCGFs were supposed to be used in seasonal frozen regions, in which the harsh ambient temperature was generally lower than that level or even lower; the other was that the minimum stable low temperature that the existing testing equipment could provide was − 30℃. So we selected − 30℃ as the minimum value. For the maximum value of temperature 20℃, it is well known that this temperature is always the conventional curing temperature for geotechnical engineering materials and can ensure that moisture evaporation has a minimum impact on the structure of samples. So such a temperature program was applied in the experiments. It should be noted that the damaged GSCGF specimens after each freeze-thaw cycle would be re-saturated in water for four hours before they were frozen again. Considering the influence of water erosion during the continuous saturation process of GSCGF, especially in later stage of freeze-thaw cycles, The test is stopped when the residual strength of GSCGF specimens was unchanged.

-

(2)

Mechanical performance test

Similarly, the unconfined compressive strength tests were also conducted on Groups A and B GSCGF specimens with compaction degrees of 89%, 92%, and 95%. When the curing age reached 24 days, the prepared specimens were placed into the water at a temperature of (20 ± 2)℃ for a four-day saturation. When the curing age reached 28 days, the microcomputer-controlled electronic universal machine measured the unconfined compressive strength of these saturated specimens after each freeze-thaw cycle. The freeze-thaw cycles similarly stopped when the residual compressive strength of GSCGF specimens was unchanged.

Experimental methods

-

(1)

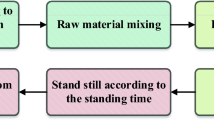

Specimen preparationThe collected natural clay was dried, crushed, and screened through a 0.075 mm sieve. The rock blocks were washed and divided into different specifications through 5 mm, 10 mm, and 20 mm sieves. According to the experimental scheme, the amounts of coarse-grained particles, sand, clay, and geopolymer binder were first weighted following the specified gradation curve and mixed dryly until they were even. Then, these mixtures were divided into four equal copies and filled into a saturator coated with the vaseline on the inner surface. The sizes of the saturator were 100 mm in diameter and 200 mm in height. The inner surface of the saturator was also covered with a layer of cling film for facilitating remolding. The whole preparation time was controlled within 30 min. Three parallel specimens were prepared for each experimental case. When finished, specimens were placed in standard curing conditions with a temperature of 20℃± 2℃ and a relative humidity of not less than 95% for 24 h. Then, they were de-molded and continued to cure until 24 days, started soaking until saturation, as shown in Fig. 4. To ensure the accuracy of the testing results for the situation where the surface of specimens was significantly damaged and particles peeled off during the freeze-thaw cycles, the upper and lower surfaces were refilled with silt slurry before the mechanical test to ensure that they were parallel and avoiding eccentric compression.

-

(2)

Testing devices and procedure.

For the mass loss rate testing before and after resaturation in water, this study employed a programmable freeze-thaw cycle chamber to simulate the environmental temperature changes since it could provide an adjustable inner temperature ranging from − 40℃ to 210℃ with a fluctuation of less than 0.5℃ and various humidity ranging from 30 to 98% automatically. During testing, specimens with different gradations and compaction degrees were subjected to programmed temperature effects from − 30℃ and 20℃ with a cosine variation in 24 h regularly. The weight of these specimens after each freeze-thaw cycle was measured before and after resaturation. Meanwhile, a microprocessor-controlled electronic universal machine was employed to investigate the compressive strength of specimens. It is designed to operate at a frequency of up to 50.0 Hz. The maximum test force is 20 kN. The loading speed range for testing is 0.001–500 mm/min with an accuracy of ± 1% (0.001–10 mm/min). The deformation measurement accuracy is ± 0.5%. The control range for constant force and displacement is 0.2-100% FS (FS is the full scale). When testing, the specimens were installed on the loading table, and the loading table was slowly raised to contact the upper-pressure plate. Then, the stress-strain data was initialized to zero, and a constant displacement of 1.0 mm/min was loaded on the specimen until it failed. This loading rate selection was followed by the literature reference and previous experience. When it was lower than 0.001 m/s, it could avoid damage or excessive deformation of the sample during the loading process, and the mechanical response under such a loading could be stable52.

Experimental results and analysis

Mass loss evolution

The damaged soil particles at the surface of GSCGF specimens will experience peeling after freeze-thaw cycles, leading to remarkable mass loss. This mass loss, on the one hand, changes the apparent compaction degree of specimens due to the loose structure near their surface; on the other hand, it reduces the effective diameter of specimens. Hence, their macro engineering performances are reduced. The mass loss rate is employed to characterize the degree of freeze-thaw damage for engineering materials. As shown in Eq. (1), the mass loss rate (ωi) of engineering materials after the ith freeze-thaw cycles can be defined as the ratio of the average mass loss of the tested specimen to its initial mass.

Where m0 is the initial mass of specimens without damage; mi is the mass of specimens after the ith freeze-thaw cycles.

Figure 5 shows the mass loss rate evolution of Groups A and B GSCGFs with different compaction degrees at various freeze-thaw cycles, in which the lower green part and upper orange part of the histogram denoted the mass loss rate of GSCGFs with different compactness before and after saturation. It could be observed that the mass loss rate of GSCGFs with the same compactness after saturation was commonly higher than that before saturation on the whole regardless of filling group and compactness. However, different increments in the mass loss rate of GSCGFs with the same compactness were illustrated at different freeze-thaw cycles. The increments in the mass loss rate of GSCGFs with the same compactness after saturation at the first freeze-thaw cycle were less than those before saturation. The increments in the mass loss rate of GSCGFs with the same compactness after saturation were approximately equal to or even higher than that before saturation as the freeze-thaw cycle was greater than three times. These differences might be due to the increase in porosity after each saturation freeze-thaw cycle. With the same freeze-thaw cycles or compaction degree, the mass loss rate of Group A GSCGFs was greater than that of Group B GSCGFs overall. The mass loss rate of Group A GSCGFs after the first freeze-thaw cycle was significantly lower than before saturation. Still, their mass loss rate before saturation was higher than after saturation after the second freeze-thaw cycle. The mass loss rate of Group B GSCGFs after saturation was approximately equal to before saturation, except for the fifth freeze-thaw cycle. These differences might be because Group A GSCGFs had a low content of fine particles and weak bonding among particles. When subjected to multiple freeze-thaw cycles, more particles peeled off the surface of Group A specimens. On the contrary, Group B GSCGFs had a relatively high content of fine particles and strong bonding among particles, resulting in good surface integrity. Although fewer particles peeled off the surface of Group B specimens, their internal bonding was continuously damaged with the increase of freeze-thaw cycles. When the freeze-thaw cycles reached a certain level, their mass loss rate would dramatically increase. Besides, it was not difficult to find that the mass loss rate of GSCGFs with the same gradation similarly increased with the decrease in compaction degree. When the freeze-thaw cycles were up to four, the surface of GSCGFs with low compaction degrees experienced severe peeling. When the freeze-thaw cycles were five, both Groups A and B GSCGFs appeared to peel remarkably. The surfaces of all specimens exhibited loose structure, and the pits formed by peeling connected each other. All these phenomena indicated that the low compaction degree of GSCGFs would result in a greater mass loss rate.

Figure 6 shows the mass loss rate evolution of Groups A and B GSCGFs with the increased freeze-thaw cycles. It could be found that GSCGFs achieved a mass loss rate of less than 5% overall when the freeze-thaw cycles were less than two but increased rapidly when more freeze-thaw cycles were subjected. This difference might be because when GSCGF specimens suffered an initial few freezing and thawing cycles, their mass loss rate was mainly caused by water loss15. When the temperature was periodically high, the water near the surface would be lost into the air rapidly, and the inner moisture in specimens would be transferred to the surface continuously due to the suction of the soil. So, the surface of GSCGFs was relatively intact, but their mass loss rate increased with the freeze-thaw cycles. When the freeze-thaw cycles reached more than three, the mass loss rate of GSCGFs increased rapidly. The frost heave force damaged the internal structure, causing internal cracking and surface peeling, which triggered an increase in water absorption, resulting in more significant mass loss. This change should be because the mass loss rate of GSCGFs mainly originated from the great damage to large-diameter pores33. Since GSCGF specimens with low compaction degrees had more pores connected to the outside, more water would enter the specimens when they were re-saturated, causing a more remarkable frost heave effect. Their mass loss rate was thus exacerbated.

Strength reduction

Figure 7 shows the compressive strength variation of GSCGFs with different compaction degrees at various freeze-thaw cycles. In the legend, such as A-95% represents Group A GSCGF with compaction degree of 95%. It could be observed that the compressive strength of Groups A and B GSCGFs with different compaction degrees decreased rapidly with the initial few freeze-thaw cycles and tended to flat as more freeze-thaw cycles were subjected. These findings were consistent with the common cognition that the freeze-thaw effect could cause the filling to develop from an unstable state to a dynamic stable state25. As the temperature decreased, some of the water in capillary pores inside the soil underwent a phase change into ice crystal, causing a volumetric expansion of waters in locals. However, the existence of the soil skeleton was bound to limit these expansions. A remarkable expansion force thus formed and squeezed soil particles around capillary pores. When the expansion force was greater than the tensile strength of GSCGFs, micro-cracks were induced and expanded outward from the capillary pores, the soil skeleton around the capillary pores was damaged, and their compressive strength decreased continuously over the freeze-thaw cycles. The water retention capacity of capillary pores would decrease with their volumetric expansion and close in on their limits with the increase of freeze-thaw cycles. So, the structural damages weakened, and their residual compressive strength tended towards stability. Besides, it could also be found that the compressive strength of Groups A and B GSCGFs with the same compaction degree was roughly equal at the initial freeze-thaw cycle. With the increase of freeze-thaw cycles, the compressive strength of Group A GSCGFs was generally greater than Group B GSCGFs when they possessed a high compaction degree. However, this rule would be reversed when they possessed a low compaction degree. The primary reason for this change may be that the Group A GSCGFs had a relatively higher rock block content. The interlocking effect among rock blocks in Group A was more significant than in Group B when their compaction degree was relatively high53,54. However, when the compaction degree was low, the limited bonding effect could not enhance the contacts among soil particles, and the structural looseness of Group A GSCGFs would be more significant than that of Group B GSCGFs. When they were saturated, more water would remain in Group A. They would cause severe structural damage in Group A GSCGFs due to the volumetric expansion of these waters with low-temperature freezing. Hence, the compressive strength of Group A GSCGFs decreased faster over the freeze-thaw cycle.

Stiffness deterioration

The slope of the straight-line section of the stress-strain curves (namely the elastic modulus) was employed to explain the stiffness variation of GSCGFs with different compaction degrees at various freeze-thaw cycles. As shown in Fig. 8, the elastic modulus of GSCGFs decreased overall with the freeze-thaw cycle. Their maximum elastic modulus reduction always appeared at the first freeze-thaw cycle, accounting for 80–90% of the total damage. Their elastic modulus would gradually stabilize when the freeze-thaw cycles reached over three. This variation may be because CCGFs were commonly regarded as the typical geo-materials with strong structure effects. Their physical and mechanical properties were significantly affected by their rock block content. The higher their volumetric rock block content, the greater the possibility of structural overhead, which could result in high pore size and pore number. When GSCGFs after saturation were subjected to freezing and thawing, the volume expansion of water would lead to the growth of pore size and pore number, structure loss, and mass loss. Typically, the internal structure of GSCGFs was severely damaged after the first freeze-thaw cycle. The size and number of internal pores within GSCGFs were significantly increased. These changes thus degraded the overall structural integrity of GSCGFs. However, as the freeze-thaw cycles increased, the contribution of the freezing effect to their structural damage was reduced. Hence, their stiffness deterioration showed a fast decrease at first and then slowed down. The deterioration of the stiffness of GSCGFs with different gradations showed that the stiffness of Group A GSCGFs decreased even more sharply than that of Group B GSCGFs. This remarkable difference implied that the rock block content significantly impacted the stiffness of GSCGFs. When specimens with the same compaction degree were subjected to the first freeze-thaw cycle, the elastic modulus reduction of Group A was about twice that of Group B. The residual elastic modulus of Group A GSCGFs with the compaction degree of 95% and 92% after freeze-thaw cycles was always more significant than that of Group B GSCGFs. However, the opposite was true at the compaction degree of 89%. This inversion might be because the skeleton structure of Group A GSCGFs was more easily deteriorated due to relatively poor contact among soil particles and a more remarkable loss of fine-grained particles after freeze-thaw cycles. Although the Group B GSCGFs had a relatively high content of fine-grained soil particles, their relatively good cementation and compaction degree would result in limited development in their internal pores. Therefore, a smaller stiffness reduction appeared in Group B GSCGFs with low compaction degree at various freeze-thaw cycles. The reason why Group A and B at different compaction degrees showed similar strength value/reduction but the elastic modulus/slope revealed a big difference might be: (1) Generally speaking, the strength of geo-materials is positively correlated with their stiffness. The higher the strength, the greater the stiffness of the material. This correlation is because the improvement of strength requires materials to have higher resistance to deformation and damage, and this improvement often requires materials to have higher stiffness. However, the relationship between strength and stiffness is not absolute. In some cases, there may be a certain contradiction between the strength and stiffness of materials. For example, some materials may experience a decrease in stiffness while increasing their strength. This is because increasing the strength of the material may require increasing the number of internal defects or changing the structure of the material, resulting in a decrease in stiffness. (2) Since the contribution of geopolymer binder to the performance improvement of CGFs mainly involved the soil matrix and the interface between the soil matrix and rock blocks and the mass ratio of the soil matrix changed with the rock block content in CGFs, this study chose the same mass mixing ratio of geopolymer binder to the dry soil matrix in the whole testing scheme as the invariant strategy. However, although the strength and stiffness of group A and B GSCGFs showed a similar attenuation law from the perspective of compaction change, the weakening bite effect and enhancing overhead structure among rock blocks would result in the low stiffness of GSCGFs as they possessed a relatively lower compaction degree. Meanwhile, the skeleton structure of Group A was more easily deteriorated due to relatively poor contact among soil particles and a more remarkable loss of fine-grained particles after freeze-thaw cycles. So the strength and stiffness of GSCGFs did not appear the same mechanical behavior.

Damage mechanism

Figure 9 shows the peeling status of Groups A and B GSCGF specimens after different freeze-thaw cycles. The horizontal direction denoted the freeze-thaw cycles, and the vertical direction denoted the compaction degree of specimens. It could be observed that the peeling of Group A GSCGFs is generally more severe than that of Group B GSCGFs. For example, when Groups A and B GSCGF specimens with 95% compaction were subjected to five freeze-thaw cycles, the mass loss rate of Group A GSCGFs reached 6.72%, and the mass loss rate of Group B GSCGFs was 4.67%. However, a remarkable peeling of surface particles always appeared when the specimens had low compaction degrees or were subjected to more freezing-thawing cycles, regardless of Group A or B filling. The lower the compaction degree of the sample, the more freeze-thaw cycles it undergoes, and the more severe the peeling of surface particles. The specimens with the lowest compaction degree could hardly maintain their initial appearance anymore after more freezing-thawing cycles. The reason for these changes should be that the destruction of GSCGF specimens was mainly caused by the damage to soil structure, and their structural damage caused by freeze-thaw cycles was significantly due to water migration and phase transition. For CGFs, a high rock block content would result in the soil skeleton having weak cementation and might cause many large open pores inside when compacted at low energy. When subjected to water infiltration, their volumetric expansion due to the phase change effect of the water would further weaken the whole filling’s structural compaction degree and particle contacts. Significant inner and surface damages were thus generated, including mass loss, strength reduction, and stiffness deterioration. As a whole, the damage of Group A GSCGFs was more severe, accompanied by the great loss of fine particles, and their soil skeleton primarily consisting of rock blocks seemed to disintegrate first from the outside, resulting in higher mass loss. However, because the internal skeleton structure with high compaction could still maintain a certain degree of integrity due to strong friction interaction, the degree of strength reduction was lower. The other difference was that the fillings with a low compaction were the opposite. When GSCGFs were subjected to five freeze-thaw cycles, the strength reduction of Group A GSCGFs with 95% compaction was about 5% lower than that of Group B GSCGFs, while the strength damage of Group A GSCGFs with 89% compaction was about 21% higher than that of Group B GSCGFs. Since the group B GSCGFs contained more fine particles, the bonding between soil and rock particles was tight, and the development of their damage rate was relatively slow as the freeze-thaw cycles increased. The contribution of the freeze-thaw effect to their structures was mainly the formation of microcracks33. When these microcracks expanded and connected during freeze-thaw cycles, they formed penetrating pore channels inside, resulting in a decrease in the sample’s water storage capacity and erosion resistance.

Damage evolution model

Existing damage model

At present, the damage factors are commonly defined following the damage mechanics. They can be mainly divided into physical mechanics and microscopic porosity. The former is mainly related to ultrasonic wave velocity, density, elastic modulus, stress, strain, etc., while the latter involves porosity, defect area, etc. Huang et al.55 proposed a damage model considering the freeze-thaw cycles through the Weibull distribution function.

Where D′ was the freeze-thaw damage factor; N was the freeze-thaw cycles; η was the characteristic lifespan parameter related to the maximum freeze-thaw cycles that the geo-materials could bear; β was the shape parameter of Weibull distribution; λ was the fitting parameter that linked the damage factors with the failure probability of the geo-materials.

Figure 10 shows the fitting results of testing data using the existing damage model. It could be observed that this model could approximately describe the relationship between the damage status of GSCGFs with high compaction degrees and the freeze-thaw cycles despite not considering more structural characteristics. However, when the compaction degree of GSCGFs was low, their fitting results slightly differed with the freeze-thaw cycles. The reason why the fitting results are significantly different in Group B while Group A seems similar might be because the strength and stiffness of GSCGFs were not only determined by their compaction degree but also closely related to their material composition and internal structure. The random distribution of rock blocks might result in a certain fluctuation in strength and stiffness. So their damage characteristics might appear different in different fillings. Besides, it should be known that the above model had three fitting parameters. The parameter λ lacked practical physical meaning. The parameters β and η were difficult to measure in practical engineering. Therefore, it was necessary to develop new models that were more suitable for GSCGFs and take more feature parameters into account.

Improved damage model

Quite evidently, the existing model just took studied geomaterials as the uniform and homogeneous medium. Except for the freeze-thaw cycle as the primary index, no other indicators with clear physical and mechanical meaning were considered. This overly simplistic empirical formula is insufficient to characterize the feature of damaged GSCGFs. Optionally, the damage factor can be defined by the strength of geomaterials subjected to freeze-thaw cycles.

Where qn denoted the unconfined compressive strength after the Nth freeze-thaw cycles; q0 was the initial unconfined compressive strength of the geo-materials.

Tan et al.56 pointed out that there was an exponential relationship between the compressive strength of the soil and the freeze-thaw cycles. Xiao et al.57 further proposed an exponential function for the compressive strength and the freeze-thaw cycles. Considering that the strength of GSCGFs decreased rapidly and then slowly down with the freeze-thaw cycles, the following empirical formula for the unconfined compressive strength of GSCGFs was proposed.

Where q was the residual strength of GSCGFs that experienced enough freeze-thaw cycles; b was the fitting parameter related to the freeze-thaw environment.

Substituting Eq. (4) into Eq. (3), an improved damage evaluation model was obtained by building an exponential relationship between the compressive strength of GSCGFs and the freeze-thaw cycles that followed the findings of previous several studies. Of course, it should be noted that this model was only feasible in cases of mild erosion since the contribution of geopolymer binder to the performance improvement of CGFs mainly involved the soil matrix and the interface between the soil matrix and rock blocks and the mass ratio of the soil matrix changed with the rock block content in CGFs and the chief culprit of quality loss just stemmed from the structural damage at the microscopic.

Figure 11 shows the fitting results of testing data using the improved damage model. It could be observed that there was a very good correlation between the testing data and the proposed damage model. The correlation coefficients of greater than 0.95 implied that the proposed empirical damage model could be used to describe the damage status of GSCGFs after each freeze-thaw cycle.

Figure 12 compares the deviation of measured and predicted damage values using the existing and improved models for GSCGFs. It could be observed that their predicted values were all distributed near the diagonal line, which indicated that both of them could be used for the damage prediction of GSCGFs. However, the improved damage model took more characteristic parameters into account, making more parameters of practical physical significance. Hence, this improved model would be more helpful in explaining the damage evolution of GSCGFs subjected to long-term freeze-thaw actions.

Conclusions

The periodic freeze-thaw effect could result in structural damage and performance degradation of GSCGFs. This study conducted a series of freeze-thaw cycles and mechanical tests on GSCGFs. The influence of gradation, compaction degree, and freeze-thaw cycles on their integrity, strength, and stiffness was investigated. Additionally, an empirical damage model considering more characteristic parameters was explored. The key conclusions were obtained as follows:

-

(1)

The mass loss rate of GSCGFs increased with the freeze-thaw cycle and decreased their compaction degree. Regardless of filling group and compaction degree, the mass loss rate of GSCGFs with the same compaction degree after saturation was commonly higher than that before saturation in the early stage. Different increments in the mass loss rate of GSCGFs with the same compaction degree were illustrated at different freeze-thaw cycles due to the increase in porosity after each saturation freeze-thaw cycle. The low compaction degree of GSCGFs would result in a greater mass loss rate after freeze-thaw cycles.

-

(2)

The compressive strength of GSCGFs decreased rapidly with the initial few freeze-thaw cycles and tended to flat as more freeze-thaw cycles were subjected. The residual compressive strength of Group A GSCGFs was generally greater than that of Group B GSCGFs when they possessed a high compaction degree. However, this rule would be reversed when they possessed a low compaction degree. The primary reason for this change may be that the Group A GSCGFs had a relatively high rock block content and was affected by an interlocking effect among rock blocks.

-

(3)

The elastic modulus of GSCGFs decreased with the freeze-thaw cycle. They appeared to have the maximum reduction at the first freeze-thaw cycle and gradually stabilized after the freeze-thaw cycles of more than three. The fact that the stiffness of Group A GSCGFs decreased even more sharply than that of Group B GSCGFs implied the significant impact of rock block content on the stiffness of GSCGFs. The weakening bite effect and enhancing overhead structure among rock blocks would result in the low stiffness of GSCGFs as they possessed a relatively lower compaction degree. The skeleton structure of Group A GSCGFs was more easily deteriorated due to relatively poor contact among soil particles and a more remarkable loss of fine-grained particles after freeze-thaw cycles.

-

(4)

The peeling of Group A GSCGFs was more serious than that of Group B GSCGFs overall. The remarkable surface peeling always appeared when the specimens had low compaction degrees or were subjected to more freeze-thaw cycles, regardless of Group A or B GSCGFs. The peeling of surface particles worsened with decreasing compaction degrees and increasing freeze-thaw cycles. High rock block content would result in the soil skeleton having weak cementation and might cause many large open pores inside when compacted at low energy.

-

(5)

The compressive strength of GSCGFs could be described by an exponential regression equation with an irrational number e as the base. An improved damage model defined by their compressive strength and freeze-thaw cycle was proposed and verified based on testing data. This improved damage evaluation model could characterize the feature of damaged GSCGFs by building an exponential relationship between the compressive strength of GSCGFs and the freeze-thaw cycles and can provide theoretical support for applying GSCGFs in engineering practices.

-

(6)

The damage of GSCGFs should include the quality loss at the macroscopic and the structural damage at the microscopic. However, considering that the chief culprit of quality loss just also stemmed from the structural damage at the microscopic, only the strength of GSCGFs and the freeze-thaw cycle was considered in the damage model. This simplified strategy is only feasible in cases of mild erosion. It would lead to significant prediction bias in cases of severe erosion. So, Balancing quality loss and structural damage should be more reliable for characterizing the damage features of geo-materials subjected to freeze-thaw cycle.

Data availability

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article. Some or all data, models, or codes that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Leng, W. M. et al. Analysis of dynamic characteristics and accumulative deformation of Coarse-Grained soil filling of Heavy-Haul railway. Rock. Soil. Mech. 36, 640–646 (2016).

Editorial Department of China Journal of Highway and Transport. Review on China’s subgrade engineering research 2021. China J. Highway Transp. 34, 1–49 (2021).

Zhang, C. X., Wang, Y., Wei, Y. F., Liang, P. & He, C. X. Research on the critical strength of the initial structure of the uncemented Coarse-Grained soil. Hydrogeol. Eng. Geol. 49, 54–63 (2022).

Cheng, G. D. & He, P. Linearity engineering in permafrost areas. J. Glaciol. Geocryol. 23, 213–217 (2001).

Li, A. Y. et al. Experimental measurement and numerical simulation of Frost heave in saturated Coarse-Grained soil. Cold Reg. Sci. Tech. 137, 68–74 (2017).

Qu, Y. L. et al. Effect of freeze-thaw cycles on uniaxial mechanical properties of cohesive coarse-grained soils. J. Mt. Sci. 16, 2159–2170 (2019).

Du, X. Y., Ye, Y. S., Zhang, Q. L. & Cheng, A. J. Experimental research on frost heaving characteristics of coarse grained soil filler of high speed railway subgrade in cold region. in Proceedings of the International Conference on Mechanics and Civil Engineering 2014 836–843. (Atlantis Press, 2014).

Wang, S. N., Gao, X. Q., Ma, W., Zhao, K. & Xu, P. W. Experimental study on static and dynamic characteristics of geopolymer-stabilized coarse-grained soils. Acta Geotech. Online (2023).

Ishikawa, T. & Miura, S. Influence of freeze-thaw action on deformation-strength characteristics and particle crushability of volcanic coarse-grained soils. Soils Found. 51, 785–799 (2011).

Xie, S. B., Qu, J. J., Lai, Y. M., Zhou, Z. W. & Xu, X. T. Effects of freeze-thaw cycles on soil mechanical and physical properties in the Qinghai-Tibet plateau. J. Mt. Sci. 12, 999–1009 (2015).

Dou, M. J., Hu, Z. S., He, Z. W. & Zhang, Y. Q. Distributing regularities of subgrade diseases in permafrost section of the Qinghai-Tibetan highway. J. Glaciol. Geocryol. 24, 780–784 (2002).

Li, S. S., Li, Z. W., Jun, H., Sun, Q. & Yu, X. Y. Investigation of the seasonal oscillation of the permafrost over Qinghai-Tibet plateau with Sbas-Insar algorithm. Chin. J. Geophys. - Chin. Ed. 56, 1476–1486 (2013).

Wu, X., Lin, Z., Niu, F., Shang, Y. & Li, C. A medium to long-term variations in hydrothermal process and deformation of high-speed railway subgrade in high-altitude cold region, Northwest China. Cold Reg. Sci. Tech. 224, 104231 (2024).

Wang, T. L., Wang, Y. & Liu, J. K. Mechanical properties of Lime-Modified soil under repeated freezing and thawing. J. China Railway Soc. 36, 109–115 (2014).

Li, X. M. et al. Strength deterioration characteristics of Lime-Metakaolin improved earthen site soil under freeze-thaw cycles. Rock. Soil. Mech. 44, 1593–1603 (2023).

Liu, F. Y., Shao, Z. S., Qiao, R. J., Zhang, S. C. & Cheng, W. C. The influence of compaction energy on Frost-Heave characteristics of Coarse-Grained soil. Nat. Hazards. 100, 897–908 (2020).

Qi, J. L., Zhang, J. M. & Zhu, Y. L. Influence of freezing-thawing on soil structure and its soil mechanics significance. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 22, 2690–2694 (2003).

Wang, Q. Z., Liu, J. K., Zhu, X. X., Liu, J. Y. & Liu, Z. Y. The experiment study of frost heave characteristics and gray correlation analysis of graded crushed rock. Cold Reg. Sci. Tech. 126, 44–50 (2016).

Bu, J. Q. & Wang, T. L. Influences of freeze-thaw and fines content on mechanical properties of Coarse-Grained soil. Chin. J. Geotech. Eng. 37, 608–614 (2015).

Gao, J. Q., Lai, Y. M., Zhang, M. Y. & Feng, Z. L. Experimental study on the water-heat-vapor behavior in a freezing Coarse-Grained soil. Appl. Therm. Eng. 128, 956–965 (2018).

Liu, J. K., Yu, Q. M., Liu, J. Y. & Wang, D. Y. Influence of non-uniform distribution of fine soil on mechanical properties of Coarse-Grained soil. Chin. J. Geotech. Eng. 39, 562–572 (2017).

She, W. et al. New insights into the Frost heave behavior of coarse grained soils for High-Speed railway roadbed: Clustering effect of fines. Cold Reg. Sci. Tech. 167, 102863 (2019).

Wang, T. L., Yue, Z. R., Ma, C. & Wu, Z. An experimental study on the frost heave properties of coarse grained soils. Transp. Geotech. 1, 137–144 (2014).

Chamberlain, E. J. & Gow, A. J. Effect of freezing and thawing on the permeability and structure of soils. Eng. Geol. 13, 73–92 (1979).

Wang, D. Y. et al. Physico-mechanical properties changes of Qinghai-Tibet clay due to cyclic freezing and thawing. Chin. J. Rock Mechan. Eng. 24, 4313–4319 (2005).

Wang, T. L., Liu, J. K., Peng, L. Y. & Tian, Y. H. Research on the mechanical properties of the cement-modified soil under the action of freezing and thawing cycles. China Railway Sci. 31, 7–13 (2010).

Peng, C. et al. Research on mechanical properties and micro-mechanics of red clay under coupled acid-etching-freeze-thaw cycles. J. Railway Sci. Eng. 1–11 (2023).

Yang, P. & Zhang, T. The physical and the mechanical properties of original and Frozen-Thawed soil. J. Glaciol. Geocryol. 24, 665–667 (2002).

Chang, D., Liu, J. K., Li, X. & Yu, Q. Experiment study of effects of freezing-thawing cycles on mechanical properties of Qinghat-Tibet silty sand. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 33, 1496–1502 (2014).

Liu, J. K., Chang, D. & Yu, Q. M. Influence of freeze-thaw cycles on mechanical properties of a silty sand. Eng. Geol. 210, 23–32 (2016).

Ahmed, M. A. & Mosleh, A. Long-Term and immediate effects of freeze-thaw cycles on the resilient modulus of treated expansive subgrades. Road. Mater. Pavement Des. 24, 2411–2424 (2023).

Li, B., Mao, J. Z., Nawa, T. & Han, T. Y. Mesoscopic damage model of concrete subjected to freeze-thaw cycles using mercury intrusion porosimetry and differential scanning calorimetry (MIP-DSC). Constr. Build. Mater. 147, 79–90 (2017).

Yang, G. S. et al. Research progress and tendency in characteristics of multi-scale damage mechanics of rock under freezing-thawing. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 37, 545–563 (2018).

Ling, X. Z., Tian, S. A., Tang, L. & Li, S. Z. A damage-softening and dilatancy prediction model of coarse-grained materials considering freeze–thaw effects. Transp. Geotech. 22, 100307 (2020).

Jia, P., Mao, S. Z., Sun, Z. Y., Qian, Y. J. & Lu, J. L. Energy evolution and piecewise constitutive model of freeze-thaw damaged sandstone. J. Cent. South. Univ. (Science Technol. 54, 908–919 (2023).

Li, B., Zhang, D., Wang, P. & Sun, M. Evolution of mechanical behaviors and microstructure of tianjin binhai cohesive soil during freeze-thaw cycles. Geofluids. 2022 9320801 (2022).

Li, B., Mao, J., Nawa, T. & Han, T. Mesoscopic damage model of concrete subjected to freeze-thaw cycles using mercury intrusion porosimetry and differential scanning calorimetry (MIP-DSC). Constr. Build. Mater. 147, 79–90 (2017).

Liu, Y., Deng, H. W., Xu, J. B., Tian, G. L. & Deng, J. R. Association study on the pore structure and mechanical characteristics of coarse-grained soil under freeze-thaw cycles. Minerals 12, 314 (2022).

Tong, X. D., Gong, X. N. & Jiang, Y. S. Elastic-plastic damage model of cement-stabilized soil. Eng. Mech. 19, 33–38 (2002).

Wang, D., Liu, E., Yang, C., Wang, P. & Song, B. Micromechanics-based binary-medium constitutive model for frozen soil considering the influence of coarse-grained contents and freeze-thaw cycles. Acta Geotech. 18, 3977–3996 (2023).

Sun, D. S., Wang, A. G. & Hu, P. H. Research of geopolymer and its applications and development prospects. Mater. Rev. 23, 61–65 (2009).

Ranjbar, N. & Zhang, M. Z. Fiber-Reinforced geopolymer composites: A review. Cem. Concr. Compos. 107, 103498 (2020).

Wang, S. N. et al. Experimental study on material ratio and strength performance of geopolymer-improved soil. Constr. Build. Mater. 267, 120469 (2021).

Qi, J. L. & Ma, W. State-of-art of research on mechanical properties of frozen soils. Rock. Soil. Mech. 31, 133–143 (2010).

Zhang, S. S., Yang, X. H., Xie, S. J. & Yin, P. J. Experimental study on improving the engineering properties of coarse grain sulphate saline soils with inorganic materials. Cold Reg. Sci. Tech. 170, 102909 (2020).

Xiao, J. et al. Probabilistic models applied to concrete corrosion depth prediction under sulfuric acid environment. Measurement 234, 114807 (2024).

Xiao, J. et al. Experimental investigation on the influence of strength grade on the surface fractal dimension of concrete under sulfuric acid attack. Buildings-Basel. 14, 713 (2024).

Ministry of Construction of the People’s Republic of China & General Administration of Quality Supervision. Inspection and quarantine of the People’s Republic of China. Standard for engineering classification of soil. In: Nanjing Water Conservancy Scientific Research Institute, Ed. GB/T50145-2007. Beijing: China Planning, (2007).

Wang, S., Xue, Q., Ma, W., Zhao, K. & Wu, Z. Experimental study on mechanical properties of fiber-reinforced and geopolymer-stabilized clay soil. Constr. Build. Mater. 272, 121914 (2021).

National Railway Administration. Code for Design of Railway Earth Structure. In: China Railway First Survey And Design Institute Group Co., Ltd, ed. TB10001-2016. (Railway Publishing House, 2016).

China Railway Corporation. Technical Specification for Construction of High-Speed Railway Earth Structure Engineering. In: Construction Management Department of China Railway Corporation, ed. QCR9602-2015. (Railway Publishing House, 2019).

Yin, X., Ge, X., Li, C. & Wang, S. Influences of loading rates on mechanical behaviors of rock materials. Chin. J. Rock Mechan. Eng. 29, 2610–2615 (2010).

Zhao, S. & Zhou, X. Effects of particle asphericity on the macro- and micro-mechanical behaviors of granular assemblies. Granul. Matter. 19, 38 (2017).

Liu, J. et al. Quantification of in situ fabric evolution and shearing behaviour of granular soils of different particle shapes. Can. Geotech. J. 61, 2450–2467 (2024).

Huang, X. G., Han, Y. Q. & Wang, T. X. Temperature field evolution in Newly-Built permafrost embankment. J. Xi’an Inst. Technol. 22, 336–341 (2002).

Tan, Y. Z. et al. Strength and micromechanism of improved silt under freeze-thaw cycle effect. Rock. Soil. Mech. 34, 2827–2834 (2013).

Xiao, Q. H., Niu, D. T. & Zhu, W. P. Experimental study on fly-ash air-entraining concrete after freezing and thawing cycles. J. Wuhan Univ. Technol. 32, 35–38 (2010).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Key Program of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 42330704), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 41902282), the Science and Technology Planning Project of Jiangsu Province, China (Grant No. BE2022605), and the Science and Technology Development Planning Project of Nanjing, China (Grant No. 202211011).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Methodology, review & editing, and funding acquisition, S.W., Z.W., S.H., and Z.S.; investigation, formal writing, and data curation, S.W., Y.X., and H.H.; investigation and original draft, S.W., and Y.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, S., Xiang, Y., Wu, Z. et al. Damage mechanism and evolution model of geopolymer stabilized coarse grained fillings subjected to repeated freeze-thaw actions. Sci Rep 15, 12166 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-94908-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-94908-z