Abstract

This study investigates the effects of microalloying elements vanadium (V) and niobium (Nb), along with varying isothermal transformation temperatures, on the microstructural evolution and mechanical properties of SWRH82B high-carbon pearlitic steel. Comprehensive microstructural characterization was conducted using optical microscopy, scanning electron microscopy (SEM), electron backscatter diffraction (EBSD), and transmission electron microscopy (TEM). The results show that the addition of V alone or in combination with V and Nb refines the lamellar spacing, pearlite clusters and pearlite ball clusters. Compared with the matrix steel, the lamellar spacing was refined by 46% at lower isothermal transitions; the dimensions of pearlite clusters and pearlite globule clusters were reduced by up to 43% and 31%.The additions of V and Nb significantly increased the microhardness, tensile strength, and yield strength of the steels. The tensile and yield strengths increased by 272 MPa and 178 MPa to 1172 MPa and 657 MPa, respectively. This increase in strength was dominated by the precipitation strengthening of VC and NbC particles and the fine grain strengthening effect. The impact toughness of pearlite steels increases with the refinement of the microstructure, which is attributed to the increase in fracture initiation energy and fracture extension energy. The increase in fracture initiation energy is greater than the extension energy under the same isothermal conditions. The fracture mode is a mixture of deconvoluted and ductile fracture. This research provides a scientific foundation for optimizing the manufacturing process of SWRH82B steel and offers significant insights into the study and application of other microalloyed high-strength steels.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The SWRH82B, a high-carbon pearlitic steel, is known for its microstructure that is either entirely composed of pearlite or a fine pearlitic structure. This structure is characterized by a predominant presence of pearlite and a subordinate fraction of ferrite and carburized particles. This specific microstructural organization is one of the key forms that the steel takes on during the slow cooling phase. The alternating growth of ferrite and carburite, necessitated by the diffusion process, results in the formation of a stratified pearlitic morphology over an extended timeframe. The development of lamellar pearlite is subject to various factors, including cooling rates, heat treatment protocols, and the steel’s alloying composition. The lamellar spacing and the dimensions of the pearlite colonies significantly impact the mechanical properties; finer lamellar spacings augment the steel’s strength and hardness, whereas wider spacings enhance its ductility and toughness. As a result, SWRH82B coils, with this microstructural organization, are extensively utilized in applications such as steel wire ropes, suspension bridge cables, and tire cords, emerging as a vital raw material for high-strength steels in sectors like construction, bridge engineering, and machinery manufacturing.

The escalating demand for high-precision and high-strength steels in industry has outpaced the capabilities of traditional alloy steels to meet increasingly stringent application criteria. Particularly in the conventional production of SWRH82B steel, the propensity for grain coarsening and microstructural inhomogeneity can lead to significant strength variability and insufficient toughness, thereby limiting its broader application due to compromised mechanical properties. To address these challenges, researchers have focused on optimizing alloy composition and thermomechanical control processes to enhance the microstructure and mechanical properties of high carbon steels. The introduction of niobium (Nb) and vanadium (V) microalloying technologies, along with isothermal transformation techniques, has garnered considerable attention in the field of steel materials. These technologies play a pivotal role in various critical applications, including modern automotive manufacturing, aerospace, large-scale construction, transoceanic bridge construction, and deep-sea tunnel engineering. In light of this, an in-depth and systematic investigation into the synergistic effects of microalloying and isothermal transformation technologies on SWRH82B steel is of significant theoretical and practical value. Such research is essential for improving material performance, streamlining production processes, reducing manufacturing costs, and bolstering the competitive edge of products in the market.

Current research indicates that microalloying technology is an effective means of enhancing the fineness of steel’s microstructure and its comprehensive mechanical properties1–4. Materials treated with microalloying exhibit superior performance characteristics, such as high strength and toughness, high elastic modulus, excellent ductility, and good workability, which suggest significant application prospects in structures subjected to heavy and dynamic loads, thus garnering extensive research attention5–8. Microalloying involves the addition of trace amounts (typically less than 1%) of alloying elements such as niobium (Nb), titanium (Ti), and vanadium (V) to steel. These elements form carbides, nitrides, or carbonitrides within the steel, leading to grain refinement, solid-solution strengthening, and precipitation strengthening. Microalloying not only improves the steel’s microstructure to enhance its strength and toughness but also enhances its corrosion resistance9, 10 and wear resistance11, 12. Over the past few decades, numerous studies have focused on the strengthening mechanisms of microalloying elements in low-carbon steel and their impact on mechanical properties13–17, while research on high-carbon pearlitic SWRH82B steel is relatively scarce.

Vanadium (V), as a microalloying element, is known as the ‘MSG of modern industry’ in the steel industry. A research team from the University of Science and Technology Beijing (USTB) has significantly improved the strength and plasticity of steel by adding trace vanadium to the steel, realising low carbon vanadium microalloying combined with an on-line, short flow hot rolling process, and successfully producing 960 MPa grade ultra-high tensile strips on an industrial scale. Vanadium is considered to be the most suitable and effective additive in high-carbon steels due to its high solubility and easy-to-control precipitation strengthening properties, and is therefore applied in high-carbon pearlitic steels18–20. In steels, vanadium-nitride (VN) is able to refine the grains and reduce the content of impurity elements in the crystal interface, thus enhancing the toughness of the material. Meanwhile, the uniformly distributed multifaceted nanophase in the matrix also plays an active role in the precipitation strengthening of the material21–23. By controlling the morphology, size and distribution of carbon and nitrogen precipitates, especially carbon nitrides, in the thermo-mechanical process, it is crucial to enhance the strength and toughness of the material. Dong24 et al. found that the precipitates become finer as the formation temperature decreases, thus providing greater strength. Significant differences in VN precipitation behaviour and strengthening mechanisms were found in different products, and the reduction in strength due to reduced manganese (Mn) and chromium (Cr) additions can be compensated for by vanadium microalloying. Ioannidou25 et al. showed significant differences in precipitation behaviour and phase transition kinetics of microalloyed steels with different vanadium and carbon concentrations at the same vanadium to carbon atom ratio.

Niobium (Nb), as a key microalloying element, has a significant grain-refining effect. In the austenitic phase, niobium precipitates in the form of carbonitrides. Strain-induced precipitation of undissolved niobium carbonitrides during high-temperature rolling pins the austenite grain boundaries, thereby inhibiting austenite recrystallization and grain growth. Additionally, fine niobium carbonitride precipitates in the ferrite region contribute substantially to precipitation strengthening, enhancing the steel’s hardness, strength, and ductility26–29. The application of niobium (Nb) microalloying technology in steel materials has garnered significant attention, particularly in low- and medium-carbon steels, where the influence of Nb on microstructural evolution and mechanical properties has been extensively investigated. However, studies on the effects of Nb microalloying in high-carbon steels have been relatively limited, with most research focusing on specific types of high-carbon steels. For instance, Arunim30 examined the role of Nb in austenitic grain growth and recrystallization kinetics in rail steels. Dey et al.31 demonstrated that high-carbon steels containing Nb (0.66% C) exhibit finer pearlitic spacing and thinner carbide layers, with superior mechanical properties compared to conventionally treated steels after tempering at specific temperatures. Recent research by Professor Jiang Zhouhua’s team32 at Northeastern University has unveiled that niobium microalloying creates a ‘niobium armor’ in duplex stainless steel, effectively encapsulating non-metallic inclusions and markedly improving corrosion resistance, thus pioneering new strategies for stainless steel corrosion protection. When the carbon content exceeds 0.8 wt%, the formation of continuous or semi-continuous grain boundary carbides is facilitated, leading to matrix embrittlement. Traditional alloy steels rely on the addition of niobium and silicon to prevent the formation of carbide networks; silicon suppresses their growth, while niobium disrupts the carbide network33. Presently, microalloying combined with thermo-mechanical control processes has become the predominant approach in the development of new ferrite-pearlitic steels, gradually phasing out conventional alloy steels.

Isothermal transformation technology represents a highly efficient heat treatment process that is capable of significantly modulating the microstructure of a material, thereby enhancing its comprehensive properties. The process enhances the mechanical properties of steel, including section shrinkage and ductility, by maintaining the steel at a specific temperature for a defined period of time, facilitating the complete transformation of pearlite, strengthening the transformation driving force, and refining the structure of pearlite clusters and lamellae. Once the pearlitic transformation is complete, the steel should be cooled at a slow rate to room temperature in order to minimise the occurrence of internal stresses and cracking.

Firstly, this study focuses on high-carbon SWRH82B steel, particularly its isothermal transformation behavior under single vanadium (V) and combined vanadium-niobium (V-Nb) microalloying conditions. Although the effects of microalloying elements such as niobium (Nb) and vanadium (V) have been extensively studied in various types of steel, research on this specific steel grade remains relatively limited34. The unique pearlitic structure and specific application requirements of SWRH82B steel highlight the necessity of exploring its behavior under microalloying and isothermal transformation conditions. Secondly, this study investigates the synergistic effects of combined V and Nb microalloying with isothermal transformation techniques on SWRH82B steel. This combination has not been fully explored in high-carbon pearlitic steels. By designing three distinct steel compositions and employing isothermal transformation techniques, we systematically analyzed the effects of microalloying and isothermal transformation on pearlite interlamellar spacing and pearlite colony size. Thirdly, this study not only experimentally examines microstructural changes but also establishes a mathematical relationship between microstructural characteristics and mechanical properties. Detailed analysis of fracture surfaces reveals the specific influence of microstructural parameters on room-temperature impact toughness, providing a scientific basis for optimizing production processes and improving product quality. Lastly, the findings of this study offer valuable insights for both the production of SWRH82B steel and the research and application of other microalloyed high-strength steels. By optimizing the types of microalloying elements and the isothermal transformation process, precise control of steel microstructure and properties can be achieved to meet the demands of various engineering applications.

Experimental procedures

Sample Preparation

The objective of this study was to investigate the effects of microalloying elements vanadium (V) and niobium (Nb) on the microstructure and properties of high-carbon pearlitic steels. To achieve this, we formulated three chemical composition schemes, ensuring that the concentrations of carbon (C), silicon (Si), manganese (Mn), and chromium (Cr) were essentially uniform across all samples. The chemical composition was accurately determined using a German Spectro direct-reading spectrometer and an American LECOONH836 analyzer for oxygen, nitrogen, and hydrogen. The detailed chemical composition data are displayed in Table 1.

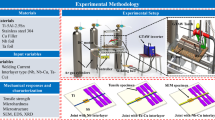

The experimental steel was smelted and cast into ingots of 340 mm height and 120 mm diameter in a vacuum induction furnace. In order to determine the appropriate austenitising temperature, the phase transition temperature at equilibrium was calculated in this study using JMatPro software and the results are shown in Fig. 1. Based on the phase diagram shown in Fig. 1, the austenitising temperature during heat treatment was set at 1200 °C and held for 10 min to ensure maximum solid solution of microalloying elements in austenite. The as-cast billet was heated at 1200 °C for 10 min to achieve homogenisation, and then forged to eliminate stress defects, with forging temperatures ranging from 1150 °C to 1100 °C, and final forging temperatures greater than 850 °C, to ultimately obtain a slab with a thickness of 30 mm. To further optimise the organisation, the slabs were austenitised again at 1200 °C and held for 10 min, followed by air cooling to room temperature. Next, isothermal transformation was carried out in a muffle furnace by holding at 710 °C, 620 °C and 550 °C for 30 min, respectively, and air-cooled to room temperature to obtain a diversified pearlitic structure. The forging and heat treatment process flow is shown in Fig. 2(a). The isothermally transformed samples were named A-i, B-i, and C-i, where the letters A, B, and C are three different compositions of steels, and i represents the temperature of isothermal transformation. For example, A-550, represents the sample of steel A isothermally transformed at 550 °C.

Microstructure characterisation and mechanical property testing

In this study, metallographic analysis was performed on small rectangular specimens, each measuring 10 mm × 10 mm × 15 mm, extracted from each sample (refer to Fig. 2(b)). The specimens were initially ground with sandpapers of varying grit sizes, followed by fine polishing with a velvet cloth and 1 μm diamond spray polish. The polished specimen surfaces were etched with a 4% ethanol nitrate solution to facilitate the observation of the microstructure under an optical microscope and a scanning electron microscope (SEM, Zeiss Sigma 300 model). To quantify the pearlite cluster size and pearlite ball cluster size, 10 to 20 representative SEM micrographs were analyzed using image analysis software (Images pro). The pearlite cluster size was determined by measuring the dimensions of areas where ferrite and carburite lamellae were alternately arranged and uniformly oriented. The layer spacing (λ) was assessed on SEM micrographs by measuring perpendicular to the pearlite lamellae using the random intercept method, with a minimum of 300 measurements per sample to ensure data reliability.

For electron backscatter diffraction (EBSD) tests, samples measuring 10 mm × 10 mm × 5 mm were prepared by wire cutting. The samples were subjected to mechanical and electrolytic polishing (using perchloric acid and ethanol solutions), and then underwent EBSD tests at an accelerating voltage of 20 kV, a scanning area of 500 μm × 500 μm, and a scanning step of 0.5 μm, with a scanning surface size of the size of the pearlitic globule clusters can be measured by EBSD mapping, for which a suitable threshold angle must be set. For pearlitic steels, this threshold angle is typically between 10° and 15°. In order to differentiate between high-angle grain boundaries (HAGB) and low-angle grain boundaries (LAGB), grain boundaries exhibiting an orientation discrepancy of over 15° are classified as HAGB, whereas grain boundaries with a discrepancy of less than 15° are designated as LAGB. Use OIM software (version 7.2) to process EBSD experimental data. Evaluate the dislocation density of the test steel using an X-ray diffractometer.

Specimens with a diameter of 3 mm and a thickness of 1 mm were extracted from the center of each sample and mechanically reduced to a thickness of 50 μm. To further decrease the sample thickness, ionic thinning was performed using a solution composed of 90% ethanol and 10% perchloric acid. The precipitated phases’ morphology and distribution were examined with a 200 kV transmission electron microscope (FEI Talos F200x) and an energy-dispersive spectrometer. TEM analysis software (Gatan Digital Micrograph) was utilized to calculate the mean pearlite layer spacing and the average carburite thickness from multiple TEM images.

Two flat tensile samples with a 28 mm scale length and a 10 mm × 2 mm scale cross-section were processed from each isothermal heat-treated sample (Fig. 2(b)). Tensile properties were evaluated using an MTS810 universal testing machine at a constant speed of 0.5 mm/min at room temperature, enabling the determination of the yield strength, tensile strength, and strain at break for each sample. Simultaneously, V-notched Charpy impact specimens were manufactured in accordance with ASTM E23-16(b), with a sample size of 55 mm × 10 mm × 10 mm (Fig. 2(b)). Charpy impact tests were conducted at room temperature, with three samples evaluated for each heat treatment condition. The fracture morphology was then observed using a scanning electron microscope. In order to ascertain the Vickers hardness, a hardness tester (Quality Assured Materialography Hardness Testing) was employed to measure under a load of 2 kg and a loading time of 10 s. To ensure the accuracy of the overall hardness of the samples, measurements were taken at 1/4, 1/2 and 3/4 positions along the thickness direction of the samples, with 10 to 20 points selected at each position to calculate the overall average hardness value.

Results

Microstructure of directly air-cooled samples

Figures 3(a)-(c) illustrate the microstructure of the three steels that were directly air-cooled after being held at 1200 °C for 10 min. The microstructural observations indicate that all three steels comprise dissolved pearlite (a brighter-coloured region) and undissolved pearlite (a darker-coloured region). The bright colour characteristics observed in the dissolved pearlite are a result of the wide spacing of lamellae, which facilitates the separation of ferrite and carburite lamellae. Conversely, the dark colour characteristics exhibited by the undissolved pearlite are due to the close spacing of lamellae, which impedes the separation of ferrite and carburite lamellae. The SEM micrographs of Fig. 3(d)-(f) are consistent with the optical microscope observation. However, some degraded pearlite (red circle in Fig. 3d) and a small amount of round carburite particles (red circle in Fig. 3f) can also be observed. Furthermore, the addition of microalloying elements V and Nb results in a gradual refinement of the spacing of the pearlite lamellae.

Explanation of the terms in the Fig. 3:

(Dissolved pearlite: Refers to pearlite in which the cementite and ferrite components have dissolved, resulting in wider lamellar spacing; Undissolved pearlite: Refers to pearlite in which the cementite and other components remain undissolved, preserving the original layered structure and characteristics, with alternating thin layers of ferrite and cementite closely stacked together Degenerate pearlite: Represents the product of pearlite degradation or decomposition under specific conditions, typically manifested as cementite spheroidization or coarsening. )

Microstructure of isothermal transition samples

To prevent grain growth and microstructural degradation, as well as to mitigate stress concentration and the propensity for cracking, this study employs an isothermal transformation technique aimed at enhancing overall structural safety. Figure 4 displays SEM images of steels without vanadium (V), with V, and with both V and Nb after isothermal treatments at 550 °C, 620 °C, and 710 °C. The microstructures of these samples are predominantly pearlitic, with some residual austenite transforming into pre-eutectoid ferrite at the higher transformation temperatures, as indicated in Fig. 4(i).

Figure 5 presents the X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns obtained during the isothermal transformation process. The XRD data reveal that only the pearlite phase was detected across the different isothermal transformation temperatures, suggesting that no new phases were formed during this process. This observation is corroborated by the SEM analysis. Furthermore, the figure displays the narrow zone scanning diffraction peaks for the (110) and (200) crystal planes of pearlite. With decreasing temperature, the diffraction peaks associated with each crystal plane broaden, the intensity of diffraction peaks enhances, and a minor rightward shift is observed.

Lamellar spacing and pearlite cluster

The average lamellar spacing of the pearlite was determined by quantitatively analyzing SEM images at various magnifications, with the results depicted in Fig. 6(a). The addition of V and Nb at different isothermal transformation temperatures refines the lamellar spacing of pearlite, suggesting that transformation temperature significantly influences lamellar spacing, with higher temperatures correlating with larger spacing. The minimum lamellar spacing is observed at the lowest transformation temperature of 550 °C, attributed to the increased nucleation sites and reduced diffusion coefficient at lower temperatures, as further discussed later. The refinement trend for microalloyed steels B and C flattens with decreasing isothermal transformation temperature compared to steel A, indicating a diminishing refinement effect. Specifically, steel A’s lamellar spacing after isothermal transformation at 550 °C decreased by 18% and 34% relative to 620 °C and 710 °C, respectively. For steel B, the lamellar spacing at 550 °C was 13.6% and 15% lower than at 620 °C and 710 °C, respectively. Steel C exhibited lamellar spacings of 145 ± 8 μm and 130 ± 8 μm after isothermal transformation at 710 °C and 550 °C, respectively, with a refinement of only 10%. Furthermore, under identical isothermal conditions, the refinement degree of lamellar spacing varied among steel grades with decreasing temperature; for instance, 28% for C-710 versus B-710, 20% for C-620 versus B-620, and 12% for C-550 versus B-550. These analyses reveal that the variation in lamellar spacing among different steel grades at the same temperature is predominantly influenced by the type and amount of alloying elements and the heat treatment process. Notably, steel A exhibits the largest lamellar spacing with the steepest increase with temperature, while steel C shows the smallest lamellar spacing with the slowest growth.

Figure 6(b) further demonstrates that the reduction in pearlite cluster size with decreasing temperature is relatively moderate, mirroring the trend observed in lamellar spacing. Regardless of the temperature, C steels with the addition of V and Nb exhibit reduced pearlite cluster sizes. At higher subcooling, the proliferation of carburite nucleation sites promotes the refinement of pearlite clusters. Conversely, at elevated temperatures, increased atomic activity enables pearlite grains to grow over a more extended period with greater energy, leading to an enlargement of pearlite cluster size as the temperature rises.

Pearlitic globule clusters

Our preceding analyses have demonstrated that microalloying elements and isothermal transformations significantly influence the microstructure of pearlite. We utilized the EBSD technique to further investigate the effects of V, Nb, and isothermal transformation on the pearlitic microstructure. A pearlite globule cluster is characterized as an area that includes an initial spheroidal nucleus, which has completed a phase transformation and developed into a spheroid, encompassing ferrite and carburite lamellae with consistent orientations. Typically, the arrangement of ferrite and carburite lamellae within a pearlitic spheroid cluster is not uniform, and a cluster may comprise multiple spheroid units35. Conventional metallographic methods cannot accurately measure the dimensions of these clusters due to the invisibility of the internal structure. EBSD, however, provides orientation data, with an orientation angle of 10°−15° set as the threshold between domains within the pearlitic spheroid cluster during analysis. This angle aligns with the defined spheroid clusters. Previous studies have shown that the diameter of the pearlite spheroid cluster is directly proportional to the initial austenite grain size36. The clusters were quantitatively identified post EBSD imaging37. The structure of the pearlitic spheroid cluster studied here is depicted in Fig. 7. Figure 7(a) presents the EBSD antipodal map, with cellular units plotted along lines a-b and c-d, representing crystal orientations at different sites. Figure 7(b) shows the distribution of grain boundaries, highlighting numerous low-angle grain boundaries (indicated by red lines in Fig. b) within the clusters, with an orientation difference of less than 15° (Fig. c). The clusters are delineated by high-angle grain boundaries. Thus, an orientation angle of ≥ 15° is designated as the boundary for pearlitic spherulitic clusters in this study. The microstructures resulting from V and V + Nb microalloyed isothermal transformations were characterized using EBSD orientation imaging (Inverse Pole Figure, IPF) maps and grain boundary (GB) maps, as shown in Fig. 8.

Due to the varying temperatures during isothermal transformation, this study employed the equivalent circular diameter method to quantitatively measure the size of pearlitic spherical clusters in the samples. Figure 9(a-f) presents the distribution of pearlite spherulite cluster sizes for three steels under different isothermal conditions, as determined by the EBSD technique. The data indicate that the size of the pearlitic spherulite clusters follows a normal distribution, represented by the red curve in the figure. The addition of microalloying elements resulted in a refinement of the average pearlite spheroidal clusters, regardless of the isothermal transformation temperature. However, the extent of refinement varied between samples isothermally treated at 620 °C and 710 °C. Specifically, in the 620 °C isothermal sample, the pearlite spherical cluster size decreased by only 1.3% for the B-620 °C sample and by 29% for the C-620 °C sample. In the 710 °C isothermal sample, the size of the pearlitic globule clusters decreased by 7.4% for the B-710 °C sample and by 25.9% for the C-710 °C sample. Compared to lower isothermal treatments, there is a slight reduction in the size of pearlite ball clusters, with or without the addition of microalloying elements.

The data presented in Fig. 9 reveal that both the peak grain size and the grain size at a 50% cumulative frequency are smaller than the average grain size. The incorporation of Nb and V leads to a progressive reduction in grain size for those grains with a cumulative frequency exceeding 90%. In the V-Nb composite-added sample C-620 °C, the grain size at a cumulative frequency above 90% is 19.5 μm, signifying a high level of refinement. Grains with a 10% cumulative frequency have an average diameter of about 1 μm. Notably, there is a pronounced difference of 6.3 μm in grain size at the 90% cumulative frequency between the C-620 °C and C-710 °C samples (refer to Fig. 9c and f). Furthermore, the average size of pearlitic globular clusters at C-620 °C is comparatively small, suggesting that the presence of large particles is minimal under lower isothermal transformation conditions.

Kernel average misorientation

Kernel Average Misorientation (KAM) describes the local orientation difference between grains, which forms geometrically necessary dislocations during plastic deformation due to the interaction of differently oriented grains. KAM is directly related to geometrically necessary dislocations, and the geometrically necessary dislocation density is calculated using the mean orientation difference. In this study, KAM was characterised using the EBSD technique. Figure 10 demonstrates the KAM distribution for different isothermal transformation temperatures and microalloyed steels containing V and Nb, where the different colours represent different stress levels, with darker areas indicating higher dislocation densities. Figure 11 presents a statistical analysis of the data, accompanied by distribution plots. The blue areas indicate lower orientation differences, while the red areas represent higher orientation differences.

As shown in Fig. 10, the combined addition of V and Nb, along with the isothermal transition temperature, significantly affects the KAM value. This value is indicative of the substantial variation in dislocation density observed within the steel. Notably, C steels with the combined addition of V and Nb display a more uniform and concentrated stress distribution, coupled with a relatively high dislocation density. The average KAM value of steel B is lower than that of steel A. This can be attributed to steel B’s finer pearlitic structure, as observed in Fig. 9, which results in a higher interface density. However, these interfaces are predominantly small-angle grain boundaries, leading to smaller local orientation differences. Additionally, the fine pearlitic structure of steel B exhibits a more uniform grain distribution and fewer grain boundary defects. These characteristics enable more efficient stress dispersion and reduced local stress concentration, thereby lowering the dislocation density and consequently the KAM value.

In contrast, the higher average KAM value in steel C is attributed to its finer pearlitic phase. Although a finer pearlitic structure typically reduces the KAM value, the fine structure of the pearlitic phase in steel C may promote greater dislocation accumulation. The elements V and Nb refine the grains and increase grain boundary density through carbide formation, providing more sites for dislocation generation and accumulation. The fine pearlitic phase in steel C results in higher grain boundary density and more grain boundary defects, which enhance local stress concentration and thus increase the KAM value.

Figure 10 presents the KAM distribution, which follows a normal distribution pattern (red curve), showing the majority of data points clustered around lower KAM values, while a few are scattered at higher values. The KAM values that account for a cumulative frequency of 50% are close to the mean KAM value, suggesting a consistent central tendency within the data set, with a concentration of values in the central region. This implies that the material’s microstructure exhibits a relatively uniform orientation distribution under these conditions, with a reduced likelihood of extreme orientation disparities. The majority of KAM values, as depicted in Fig. 11, are concentrated between 0 and 3 degrees, primarily due to dislocation accumulation. In contrast, the higher KAM values observed beyond 3 degrees are mainly influenced by grain boundaries.

TEM characterisation

Steels B and C, isothermally treated at 710 °C and 620 °C respectively, were selected for detailed morphological and phase precipitation analysis using transmission electron microscopy (TEM). Figure 12 depicts the lamellar structure of ferrite and carburite within pearlite clusters, captured under TEM’s bright field. These lamellae exhibit uniform thickness, and the spacing statistics of the pearlite lamellae align closely with those from scanning electron microscopy (SEM) observations. The figure also presents the statistical data for carburite thickness (CT). Dislocations within the ferrite are arranged in a bamboo-like configuration (indicated by blue arrows), with their termini anchored at the interfaces of adjacent carburite lamellae. Predominantly, dislocations are concentrated at the ferrite-carburite boundary (marked by red arrows), with only a few dislocations found within the ferrite lamellae themselves. In the V and Nb-alloyed samples, a notably high dislocation density is observed at the ferrite-carburite interface and within the ferrite lamellae, forming an intricate dislocation network (highlighted by white arrows). Figure 13 displays the energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) results and the morphology of the precipitates, revealing that the precipitates measure approximately 30–60 nm in size. Through EDS and selected area diffraction pattern (SADP) analyses (Fig. 13), the precipitates were identified as having a face-centered cubic (FCC) crystal structure. In the B-620 °C sample, the precipitate was identified as VC (Fig. 13a). In contrast, both V and Nb were detected in the precipitates of the C-710 °C sample, confirming the presence of V- and Nb-containing precipitates, which are composite precipitates of VC and NbC. These findings are consistent with the equilibrium phase diagram discussed earlier. Additionally, the selected diffraction patterns of the precipitates are shown in Fig. 13a and d. Both VC and NbC particles exhibit spherical and elliptical morphologies. The average particle size was measured using statistical methods.

Mechanical properties

Microhardness measurement

Figure 14 presents the microhardness measurements of the experimental steels. Microalloyed samples, namely steels B and C, exhibit higher microhardness compared to steel A across all isothermal transformation temperatures (550 °C, 620 °C, and 710 °C). The microhardness decreases with decreasing isothermal temperature, reflecting an inverse relationship between these variables. The trend is depicted in two stages within Fig. 14. In the first stage, as the temperature drops from 710 °C to 620 °C, hardness increases nearly linearly, with steels A, B, and C showing respective increases of 12%, 7%, and 12%. In the second stage, from 620 °C to 550 °C, the rate of hardness increase markedly slows, with steel B’s hardness increasing by only 3%.

Tensile properties

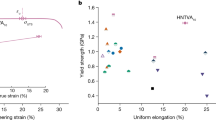

In conducting the tensile experiments, Fig. 15 displays the typical engineering stress-strain curves for high carbon pearlitic steels, indicating the discontinuous yielding behavior of the material. The yield strength was determined using the stress value that produced 0.2% residual deformation, as none of the specimens displayed a distinct yield point. Material ductility was characterized by the total elongation at the strain at break. To obtain mean values, three tensile tests were performed for each condition, with the results presented in Table 2, including tensile strength, yield strength, elongation, and the ratio of yield strength to maximum tensile strength at three different temperatures and under air-cooled conditions. Figure 15, in conjunction with the data in Table 2, shows that the isothermally transformed samples generally exhibit higher elongation values than the air-cooled treated samples, surpassing 10%.

Further analysis of Fig. 15(a-c) reveals that the addition of vanadium (V) significantly enhanced both the yield and tensile strengths of the test steels across three distinct isothermal transformation temperatures. For instance, the A-620 °C specimen exhibited yield and tensile strengths of 545 MPa and 995 MPa, respectively, whereas the B-620 °C specimen demonstrated increased values of 586 MPa and 1069 MPa, corresponding to increments of 41 MPa and 74 MPa, respectively. Although the elongation of the B-620 °C specimen was marginally reduced compared to the A-620 °C specimen, it remained at 13.6%, decrementing by only 1.1%. When vanadium (V) and niobium (Nb) elements were added compositely, the yield and tensile strengths were further increased significantly. The yield and tensile strengths of the C-620 °C specimen were 657 MPa and 1172 MPa, respectively, which were 272 MPa and 178 MPa higher compared with that of the A-710 °C specimen, while the elongation was maintained at 12.7%. This enhancement is likely due to the alloying promotion by V and Nb, which inhibits austenite recrystallization nucleation and growth through solute drag effects or precipitation formation, thereby refining the grain spacing, pearlite clusters, and pearlite globule clusters.

Additionally, Fig. 15(d-f) indicates that specimens subjected to lower isothermal transformation temperatures display elevated yield and tensile strengths, albeit with a marginal decrease in ductility. These findings suggest that the mechanical properties of high-carbon pearlitic steels can be effectively tailored by precisely controlling the microalloying element addition and the temperature of isothermal transformation.

(a) Engineering stress-strain curves of Steel A, Steel B, and Steel C at 550 °C; (b) Engineering stress-strain curves of Steel A, Steel B, and Steel C at 620 °C; (c) Engineering stress-strain curves of Steel A, Steel B, and Steel C at 710 °C; (d) Engineering stress-strain curves of Steel A at different temperatures (550 °C, 620 °C, and 710 °C); (e) Engineering stress-strain curves of Steel B at different temperatures (550 °C, 620 °C, and 710 °C); (f) Engineering stress-strain curves of Steel C at different temperatures (550 °C, 620 °C, and 710 °C).

Impact properties

Impact toughness is a critical measure of a material’s capacity to absorb energy and withstand damage when subjected to impact loading. Figure 16 presents the impact test force-displacement curves for the experimental steels under three distinct isothermal transformation conditions following microalloying treatment. Here, the green curve represents the original force curve, while the blue curve denotes the fitted force curve. By integrating the area under these curves, we determined the fracture initiation energy (indicated by the red dashed line in the figure) and the fracture extension energy. The red curve illustrates the variation of impact absorption energy with displacement, where Fm signifies the maximum stress value that the material attains during impact, that is, the peak force value in the fitted curve. Beyond this value, a sharp decrease in the curve signifies the commencement of crack propagation.

Figure 17 encapsulates the Charpy total impact energy outcomes for the three isothermal transformation conditions, encompassing both fracture initiation and extension energies. Synthesizing the data from Figs. 16 and 17, it becomes evident that the curve variations are temperature-dependent, particularly at lower temperatures where the peak force is more pronounced. As the isothermal temperature decreases, the total impact absorption energy of the material increases by 4.42 J, indicating that the impact toughness of steel improves with the decrease of isothermal temperature. Steels fortified with microalloying elements such as vanadium (V) and niobium (Nb) exhibit superior impact properties at equivalent temperatures. Both the varying isothermal temperatures and the incorporation of elements V and Nb have a pronounced impact on the steel’s impact toughness, with the specific behavior of this effect being contingent upon the steel’s chemical composition and microstructure. The underlying microscopic mechanisms will be delineated in the subsequent section.

Discussion

Effect of microalloying on phase transformation

In this study, the equilibrium phase behavior of three experimental steels with different compositions—Steel A, Steel B, and Steel C—was analyzed in detail over the temperature range of 0–1600 °C using thermodynamic model calculations. Figure 1 presents the equilibrium phase diagrams of these steels, which reveal the presence of liquid, austenite, ferrite, carbide (M7C3), M2P, and MnS phases. The addition of vanadium (V) and niobium (Nb) to Steel B and Steel C significantly influences the precipitation behavior of phases such as MN, M(C, N), and M23C6, compared to Steel A. In this section, we focus on the influence of microalloying elements (V and Nb) on the phase transformation process, including austenite formation and decomposition, precipitated phase behavior, and elemental partitioning.

Austenite formation and decomposition behavior

Figure 18 illustrates the variation in austenite elemental composition with temperature. Austenite begins to form at 1458 °C, with alloying elements (e.g., C, Cr, Mn, etc.) rapidly dissolving into the austenite phase. As the temperature decreases to 1335 °C, the liquid phase is completely transformed into austenite. In Steel B and Steel C, the addition of V and Nb promotes the precipitation of phases above 1000 °C, leading to a significant reduction in the V and Nb content within the austenite. When the temperature drops to 812 °C, austenite gradually decomposes into cementite and other precipitated phases. Concurrently, the contents of C, Cr, and Mn decrease, while those of Si and P gradually increase with decreasing temperature. At 752 °C, austenite rapidly decomposes into ferrite and is completely transformed by 737 °C.

The addition of microalloying elements (V and Nb) significantly influences the stability of austenite. As strong carbide-forming elements, V and Nb preferentially combine with C and N to form carbonitrides (e.g., MN and M(C, N)) at elevated temperatures. This behavior reduces the activities of C and N in the austenite, thereby slowing down the austenite decomposition process. This phenomenon is particularly evident in Steel B and Steel C, highlighting the crucial role of microalloying elements in regulating phase transformation kinetics.

Relationship between precipitation phase behavior and temperature

The addition of microalloying elements significantly influences both the type and quantity of precipitated phases and their variation with temperature. Figure 19 illustrates the elemental composition of the precipitated phases as a function of temperature. In Steel B, the MN and M(C, N) precipitates begin to form at 1000 °C, with the amount of precipitation increasing rapidly as the temperature decreases, and then decreasing sharply at 752 °C. The M(C, N) phase, whose constituent elements include Cr, V, N, and C, exhibits a rapid increase in precipitation amount with decreasing temperature. When the N content exceeds that of C, VN predominantly forms; conversely, V(C, N) forms when the C content is higher.

In Steel C, the MN and M(C, N) precipitates begin to form at 1313 °C. As the temperature decreases, the Nb content gradually decreases while the V content increases. At high temperatures, Nb tends to combine with C and N to form Nb(C, N), whereas VC is more soluble. As the temperature decreases, the transformation of austenite to ferrite or pearlite reduces the solubility of NbC and promotes the precipitation of NbC, thus reducing the content of Nb in the solid solution state. Although the solubility of VC decreases, its precipitation is delayed due to the stability of the austenite phase, allowing VC to dissolve temporarily in austenite and increase the V content. This behavior indicates that the precipitation of V and Nb is closely related to temperature and is influenced by the stability and solubility of the austenite phase.

Elemental assignment during phase transitions

In Steel C, the distribution of V and Nb during phase transformation is significantly influenced by temperature. At 752 °C, the V content decreases sharply before increasing, while the Nb content increases sharply before decreasing. These changes are associated with shifts in the thermodynamic equilibrium state of the system. During the transformation from austenite to ferrite, carbon diffuses from ferrite to austenite to maintain the chemical potential balance of carbon in the two phases. When the temperature reaches 752 °C, VC begins to precipitate from austenite, forming particles and leading to a sharp decrease in V content. Meanwhile, with the complete disappearance of austenite at 737 °C, the ferrite phase stabilizes, reaching a maximum volume fraction of 88%, and the V content gradually increases. Additionally, due to ferrite formation and carbon redistribution, NbC may redissolve in ferrite, causing a sharp increase in Nb content. However, as the temperature decreases further and phase transformation continues, the precipitation and dissolution of NbC and VC reach a new equilibrium state, adjusting the V and Nb contents accordingly. This process highlights the complexity of elemental distribution during phase transformation, indicating that microalloying elements (V and Nb) not only affect the type and amount of precipitated phases but also modulate microstructural evolution by altering elemental distribution behavior.

In summary, the variation in V and Nb content in steel is closely related to their carbide-forming tendencies, the stability of austenite and ferrite phases, and the phase transformation behavior induced by temperature changes. By precisely controlling the content and distribution of these elements, the microstructure and mechanical properties of steel can be optimized.

Effect of V and Nb on microstructure

As illustrated in Figs. 3 and 4, the addition of V and Nb has been demonstrated to be an effective method for refining the spacing of pearlite lamellae, as well as the distribution of pearlite clusters and globule clusters. This has been observed under both air-cooled conditions and under different isothermal transformation conditions. In the case of high-carbon steels organised as pearlite, the addition of the V element serves to narrow the region of the austenite phase. The addition of V results in an increase in the A1 and A3 temperature points, which in turn leads to greater subcooling and thus a finer lamellar spacing. Furthermore, the addition of V and Nb, which are strong carbide-forming elements, results in the formation of precipitated phases with carbon. These elements also consume carbon and hinder its diffusion, limiting the long-range diffusion of carbon atoms and slowing down their diffusion. This ultimately leads to a reduction in the lamella spacing. The driving force for the pearlitic transformation can be attributed to a reduction in the bulk free energy, while the resistance can be attributed to an increase in the interfacial energy and the overcoming of the diffusion-activated energy barrier required for the redistribution of the alloying elements. Therefore, the total driving force of the pearlite transition is employed to form a new phase interface on the one hand and to overcome the diffusion energy barrier on the other. As demonstrated by Liu et al.38, the non-equilibrium distribution of Nb between the Fe/Fe₃C interfaces serves to reduce the local driving force, thereby facilitating the refinement of the pearlitic lamellae spacing to a certain extent.

The refinement of pearlite clusters and pearlite globule clusters is inextricably linked to the growth rate of pearlite. From a thermodynamic perspective, the transformation of pearlite typically entails a period of nucleation and growth, both of which are influenced by the diffusion of carbon atoms in the austenite39, 40. The study by Pham and colleagues41 demonstrated that the duration of this transformation is directly proportional to the diffusion activation energy of the carbon atoms. An extension of the gestation period will result in a reduction in the growth rate of the pearlite, which will in turn lead to a decrease in the size of the pearlite cluster. The relationship between pearlite growth and the diffusion rate of carbon atoms is typically described using the Zener-Hillert model42. According to this model, the growth rate of pearlite is directly proportional to the diffusion coefficient of carbon atoms. This relationship underscores the critical role of the carbon diffusion coefficient in pearlite formation.

Considering the role of V and Nb, the relationship between the diffusion coefficient of carbon atoms and temperature is given from the literature as43。The diffusion coefficient of carbon atoms decreases with decreasing temperature. In Steel B and Steel C, the addition of vanadium (V) necessitates considering the combined effect of V and niobium (Nb) on the parameter XNb, given that V has similar chemical properties to Nb and also inhibits carbon diffusion. According to the Zener-Hillert model, the addition of microalloying elements reduces the diffusion coefficient of carbon atoms, thereby slowing the growth rate of pearlite. Zhou et al.1 confirmed via high-temperature laser scanning confocal microscopy that the primary reason for the reduced pearlite growth rate upon Nb addition is the decreased carbon diffusion coefficient. Although the effects of microalloying elements on pearlite cluster size are relatively minor, this does not imply a lack of influence. Figure 9 further illustrates the distribution of pearlite cluster sizes. The formation of pearlite clusters is primarily governed by nucleation and growth processes, which are less sensitive to microalloying elements. In contrast, lamellar spacing is more dependent on fine precipitates and phase transformation kinetics. Pearlite cluster size is influenced not only by nucleation but also by elemental diffusion during subsequent isothermal processes. The degree of alloying element partitioning increases with isothermal time, potentially affecting residual austenite stability and, consequently, pearlite cluster size. Additionally, microalloying elements tend to segregate at austenite grain boundaries, which may alter the austenite/pearlite interfacial energy and affect the nucleation size and growth direction of pearlite clusters. The stable precipitates formed by V and Nb act as barriers during pearlite transformation and pin grain boundaries, implying a refinement of pearlite clusters.

Figure 3 illustrates that the lamellar spacing of pearlite decreases with decreasing temperature. Notably, steels B and C, which contain added V and Nb, exhibit a more refined lamellar structure during isothermal transformation. The lamellar spacing is governed by the degree of subcooling, as described by the semi-empirical formula proposed by Hillert44:

\(\:{\uplambda\:}=\frac{4{\upsigma\:}{\text{T}}_{\text{E}}}{\varDelta\:\text{H}\left({\text{T}}_{\text{E}}-\text{T}\right)}\), λ is the pearlite lamellar spacing,σ is the ferrite-carburite interfacial energy, TE is the equilibrium transition temperature of pearlite,ΔH is the change in enthalpy per unit volume during the transformation, and TE−T represents the degree of subcooling. Hillert’s formula suggests that lower isothermal temperatures result in increased subcooling and finer pearlite lamellar spacing. Moreover, the diffusion coefficients of carbon atoms in B and C steels are reduced by the presence of V and Nb in solid solution, and these coefficients decrease further with decreasing isothermal temperature, leading to a reduced growth rate of pearlite. As a result, the pearlite clusters, cluster sizes, and lamellar spacing in the C-550 °C sample are finer compared to those in the A-710 °C sample.

Relationship between microstructure and strength

A comprehensive assessment of the aforementioned analyses demonstrates that the trends of pearlite lamellae spacing, pearlite clusters and pearlite clusters exhibit a high degree of consistency following microalloying and isothermal transformation treatments. As illustrated in Figs. 6, 9 and 12, the impact of isothermal transformation on hardness is comparatively minor, whereas the influence of microalloying treatment on microhardness is more pronounced. Additionally, Liu45 highlighted in a related study that the incorporation of elements V and Nb can enhance the refinement of steel microstructure and facilitate the formation of diffusely distributed second-phase particles within the ferrite matrix. These particles are characterised by their small size and contribute to the improvement of the material’s strength and hardness. The effect of these elements on strength is also consistent, as evidenced by the data presented in Fig. 12; Table 2. The relationship between hardness and ultimate tensile strength (UTS) and yield strength (σY) can be estimated by means of Eqs. (1) and (2)46.

These equations are applicable for estimating the strength within the hardness range of 300–400 HV, where the hardness is measured under a 5 kg load. Although in this study, the hardness was measured under a 2 kg load, the calculated results demonstrate a good agreement between the experimentally determined tensile properties and those estimated based on hardness (see Tables 2 and 3).

σ0 represents the lattice friction stress of iron, σSS denotes solid solution strengthening, σg signifies grain strengthening, σP indicates precipitation strengthening, and σd corresponds to dislocation strengthening.

To quantitatively analyze the strengthening mechanisms of high carbon pearlitic steel, we selected two isothermal conditions, 620 °C and 710 °C, for detailed examination. The yield strength of high carbon pearlitic steel is directly influenced by the size of pearlite colonies and lamellar spacing, which contribute to grain strengthening in accordance with the Hall-Petch relationship. The relationship is expressed as follows38:

L represents the size of the pearlite colony, and λ denotes the lamellar spacing within pearlite. The dimensions of the pearlite colony and lamellar spacing have been ascertained as depicted in Fig. 6.

Dislocation strengthening is mainly determined by dislocation density, which is closely related to KAM. The relationship between geometrically necessary dislocations (GND) and KAM is as follows47:

\(\:\alpha\:\) is a constant associated with the crystal structure, approximately 0.24, M is the Taylor factor (1.84 for non textured bcc crystals), G is the shear modulus (80650 MPa for steel), b is the Burgers vector (0.248 nm), ρ is the dislocation density per unit area (m−2). Dislocation density comprises both statistical storage dislocation density (SSD) and geometrically necessary dislocation density (GND). The local orientation differences measured by KAM values in this study are closely related to GND but only reflect the local strain distribution and cannot directly quantify the total dislocation density. To address this limitation and accurately estimate the effect of dislocation strengthening, this study employs an improved Williamson-Hall method to analyze the X-ray diffraction pattern (see Fig. 20(a)), thereby estimating the total dislocation density and further evaluating the degree of dislocation strengthening. The relevant formula is as follows:

During the structural optimization process, the normalized peak intensity was fitted using a Gaussian function. In this context, λ represents the X-ray wavelength (λ = 0.15418 nm), β denotes the integrated peak width, b is the Burgers vector, and θ is the diffraction angle. The grain size (D) and microstrain (ε) were subsequently determined using the improved Williamson–Hall formula (Eq. (6)). Specifically, by plotting β cos(θ) against 5·sin(θ), the intercept and slope of the linear relationship were obtained, which enabled the calculation of the grain size (D) and microstrain (ε), see Fig. 20(b). The dislocation density was then calculated using Eq. (7) (as detailed in Table 4). From Table 4, it can be seen that the dislocation density of the samples is within one order of magnitude, ranging from 2.148 × 1014 m−2−2.707 × 1014 m−2. Finally, the dislocation strengthening value was estimated by combining the results with Eq. (5). Compared to B steel with added V alone, the contribution of dislocation strengthening in C steel has increased slightly, but the increase is not significant.

The Ashby Orowan equation can be used to derive the precipitation strengthening caused by precipitation, and the relationship is as follows50:

\(\:{{\upsigma\:}}_{p}\) represents precipitation strengthening (MPa); f is the volume fraction of precipitates (%); d is the average diameter of the precipitated particles (nm); G is the shear modulus (80650 MPa for steel); b is the Burgers vector (0.248 nm); K is the coefficient, \(\:\frac{1}{k}=\frac{1}{2}\left(1+\frac{1}{1-v}\right)\), where v is Poisson’s ratio, v = 0.291; Substituting the constant yields:

The formula clarifies that precipitation strengthening is predominantly governed by the volume fraction of precipitates and the average diameter of the precipitated phase. Hence, achieving a higher volume fraction of finely dispersed precipitates is essential for effective precipitation strengthening. Given the negligible nitrogen content in the experimental steel, the nitride precipitation phase is not considered in this analysis. To ascertain precise measurements of the precipitate dimensions d and the interparticle spacing f, 5–10 high-resolution TEM images were analyzed utilizing Image-Pro Plus software.

Solid solution strengthening, which is associated with the chemical composition, varies significantly among the three steels studied in this paper, primarily due to differences in the addition of niobium (Nb) and vanadium (V). Following the methodology outlined by Yong51, the contribution of solid solution strengthening from elements such as silicon (Si), manganese (Mn), and chromium (Cr) was predominantly calculated.

The percentage of N in the solid solution state of the steel can be disregarded due to the robust combining ability of N and the microalloying elements Nb and V. The strengthening coefficients and additions of Nb and V are minimal, and the incremental increase in their solid solution strengthening is inconsequential. According to the composition of the steel alloy in this experiment (as shown in Table 1), the solid solution strengthening was calculated. Based on the calculation of the above experimental data, the contribution of each strengthening is shown in Fig. 21.

The combined analyses demonstrate that the addition of V and Nb significantly enhances the strength of high-carbon pearlite steels. Furthermore, the strength is observed to increase as the isothermal transition temperature decreases. This phenomenon is primarily attributable to the intensification of fine grain strengthening and precipitation strengthening. In particular, the combination of V and Nb results in a slight enhancement of the dislocation strengthening contribution of C steels compared to the addition of V alone. In terms of the effect of microstructure on strength, the reduction of the pearlitic lamellae spacing, the refinement of grain size, and the enhancement of precipitation relative strength represent the primary strengthening mechanisms.

Effect of lamella spacing on impact toughness

Higher macroscopic deconstructive fracture stresses render deconstructive fracture less probable52. Sreenivasan53 et al. employed an integrated approach, combining impact tests with slip line field theory, to approximate the maximum normal stress in front of the notched root as equivalent to the macroscopic deconstructive fracture stress. It was demonstrated that the pearlitic lamellar spacing is correlated with the deconvolutional fracture stress, which increases as the lamellar spacing becomes smaller54. Figure 6(a) illustrates that microalloying can refine the lamella spacing to a greater extent than isothermal transformation. Figure 17 additionally corroborates that B and C steels possess finer lamella spacing, greater total impact absorbed energy, and exhibit superior impact properties compared to A steels. As the temperature decreases, the lamella spacing is further refined, resulting in an increase in the total impact energy. It can therefore be concluded that the combination of microalloying and the isothermal transformation technique represents an effective method for improving impact toughness.

The interface between ferrite and carburite in pearlite can be conceptualised as a grain boundary. With regard to phase interfacial energy, a reduction in lamella spacing results in an elevated phase interfacial energy between ferrite and carburite. The higher interfacial energy induces the bending and entanglement of dislocations at the interface, which requires greater energy expenditure and enhances the material’s resistance to deformation. A reduction in lamella spacing results in an increase in the number of grain boundaries. The interface between ferrite and carburite becomes more compact, and the grain boundaries can effectively impede the movement of dislocations. Consequently, grain boundary reinforcement is enhanced, which improves the toughness of the material. Conversely, a larger lamella spacing results in a relatively loose interface between ferrite and carburite, thereby enhancing the grain boundary weakening effect and reducing the toughness of the material.

In order to gain a deeper understanding of the underlying causes of the observed differences in toughness, we have identified two key stages in the fracture process: crack initiation and crack extension. These stages have been delineated using force-displacement curves, which are presented in Fig. 16. The region between 0 and Fm (maximum force) is considered to represent the crack initiation stage, and the corresponding work is indicative of the fracture initiation energy. The remaining region is considered to represent the crack extension stage, and the corresponding work is indicative of the fracture extension energy. The data pertaining to the initiation and extension energies for each specimen are presented in Fig. 17. The results demonstrate that both B and C steels, when subjected to the addition of V and Nb, exhibit an increase in both fracture initiation energy and fracture extension energy. In accordance with the isothermal conditions, the augmentation in fracture initiation energy is more pronounced than that observed in the extension energy. In particular, for C steels with composite additions of V and Nb, the effect of lamella spacing on impact toughness is negligible when the isothermal temperature decreases to below 150 nm lamella spacing.

Figure 22 depicts scanning electron microscope (SEM) images of Charpy impact fractures. The majority of the fractures exhibited a river-like pattern and distribution of tough nests, the presence of tough nests on the tearing prongs, and flat and smooth bottoms of the tough nests, which indicated a typical hybrid fracture pattern, i.e., the coexistence of deconvolutional and ductile fracture. Upon reaching the limit of stress, nucleation sources within the specimen form minute holes, which subsequently develop into tough nests. These microholes then grow and coalesce, leading to the formation of cracks and ultimately, the fracture of the specimen. The impact fracture of B and C steels is characterised by a greater number of tear ribs and a larger distribution area of tough fossae. These are accompanied by fossae of varying sizes and depths, which enable the specimens to absorb more energy when subjected to force. This can be attributed to the higher impact absorbed energy observed in these specimens. The smaller lamella spacing increases the resistance to crack extension. When the crack encounters the closely spaced pearlitic lamellae, it requires a greater amount of energy to continue extending, thereby enhancing the impact toughness of the material. In conclusion, the impact toughness of high-carbon pearlite steels is primarily influenced by the strengthening and weakening of grain boundaries, phase interfacial energy, and crack extension resistance, which are affected by lamella spacing. The impact toughness of high-carbon pearlite steel can be enhanced effectively by regulating the isothermal transformation and microalloying processes in order to diminish the pearlite lamella spacing.

Conclusion

This study meticulously investigated the effects of vanadium (V) and niobium (Nb) additions, along with varying isothermal transformation temperatures, on the microstructural evolution and mechanical properties of SWRH82B pearlitic steel. Extensive microanalysis utilizing scanning electron microscopy (SEM), electron backscatter diffraction (EBSD), and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) was performed to elucidate the fracture mechanisms. The conclusions drawn are as follows:

(1) The precipitated phases in B and C steels start to form above 1000 °C, and as the temperature decreases, the concentration of V and Nb in austenite decreases while their precipitation increases up to 0.11%. In C steels, the contents of V and Nb show an inflection point at 752 °C, with the V content experiencing a rapid decrease followed by an increase, while the Nb content increases rapidly followed by a decrease.

(2) As the isothermal transition temperature decreases, the degree of subcooling increases, resulting in a finer lamellar spacing.The addition of V and Nb effectively hinders the diffusion of carbon and slows down the growth rate of pearlite. At lower temperatures, the addition of trace amounts of V resulted in a 38% refinement of the pearlite lamellae spacing, while further compound addition of V and Nb resulted in a 46% refinement of the lamellae spacing. The size of the pearlite clusters and pearlite clusters were reduced by up to 43% and 31%.

(3) The addition of V and Nb significantly increased the microhardness, tensile strength and yield strength of the steel at lower isothermal transition temperatures. The increase in microhardness was in good agreement with the increase in strength. Compared with the matrix steel, the tensile and yield strengths reached 1172 MPa and 657 MPa, an increase of 272 MPa and 178 MPa, respectively. The increase in strength is mainly dominated by the fine grain strengthening effect, while the precipitation of VC and NbC particles also contributes to the strength improvement, but its effect is relatively small.

(4) The fracture toughness of pearlitic steels increases with the refinement of the microstructure, and the fracture initiation energy and fracture extension energy increase. Under the same isothermal conditions, the increase in fracture initiation energy is greater than the extension energy. The fracture mode is a mixture of deconvoluted fracture and ductile fracture.

Data availability

Availability of data and materials: All relevant datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are within the paper.

References

Zhou, M. X. et al. New insights to the metallurgical mechanism of Niobium in high-carbon pearlitic steels. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 26, 1069–1623 (2023).

Han, K., Mottishaw, T. D., Smith, G. D. W., Edmonds, D. V. & Stacey, A. G. Effects of vanadium additions on microstructure and hardness of hypereutectoid pearlitic steels. Mater. Sci. Eng. A. 190 (1–2), 207–214 (1995).

Godefroid, L. B. et al. Effect of chemical composition and microstructure on the fatigue crack growth resistance of pearlitic steels for railroad application. Int. J. Fatig. 120, 241–253 (2019).

Sanz, L., Pereda, B. & López, B. Effect of thermomechanical treatment and coiling temperature on the strengthening mechanisms of low carbon steels microalloyed with Nb. Mater. Sci. Eng. A. 685, 377–390 (2017).

Zhang, X. D. et al. Dislocation-based plasticity and strengthening mechanisms in sub-20 Nm lamellar structures in pearlitic steel wire. Acta Mater. 114, 176–183 (2016).

Savrai, R. A., Makarov, A. V., Malygina, I. Y. & Volkova, E. G. Effect of nanostructuring frictional treatment on the properties of high-carbon pearlitic steel. Part I: microstructure and surface properties. Mater. Sci. Eng. A. 734, 506–512 (2018).

Huang, L. H. et al. Atomic interactions between Si and Mn during eutectoid transformation in high-carbon pearlitic steel. J. Appl. Phys. 126, 245102 (2019).

Tian, J. Y. et al. Improving mechanical properties in high-carbon pearlitic steels by replacing partial V with Nb. Mater. Sci. Eng., A. ; 834. (2022).

Zambrano, O. A. & Jiang, J. The effect of VC content on the scouring erosion resistance of tool steels. Wear ; 520–521. (2023).

Tu, Y. W., Zhu, L. H., Zhou, R. Y., Hu, H. B. & Huang, Y. P. Effect of vanadium addition on the corrosion behavior of S30432 austenitic heat-resistant steel aged at 650 ◦C for different times. J. Mater. Sci. 57 (29), 14096–14118 (2022).

Liao, X. Y. et al. Achieving high impact–abrasion–corrosion resistance of high–chromium wear–resistant steel via vanadium additions. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 29, 2425–2436 (2024).

Mohammadnezhad, M., Javaheri, V., Shamanian, M., Naseri, M. & Bahrami, M. Effects of vanadium addition on microstructure, mechanical properties and wear resistance of Ni-Hard4 white cast iron. Mater. Des. 49, 888–893 (2013).

Seung, K. B., Won, Lee, C. & Hoon, L. Y. A study on Nb-V microalloyed steel for 460 mpa grade H-section columns. J. Const. Steel Res. 170, 106112 (2020).

Zaitsev, A. & Arutyunyan, N. Low-Carbon Ti-Mo microalloyed hot rolled steels: special features of the formation of the structural state and mechanical properties. Metals 11 (10), 1584–1584 (2021).

Gong, P., Palmiere, E. & Rainforth, W. Dissolution and precipitation behaviour in steels microalloyed with Niobium during thermomechanical processing. Acta Mater. 97, 392–403 (2015).

Yuan, S. Q., Liang, G. L. & Zhang, X. J. Interaction between elements Nb and mo during precipitation in microalloyed austenite. J. Iron Steel Res. 17 (9), 60–63 (2010).

Charleux, M., Poole, W. J., Militzer, M. & Deschamps, A. Precipitation behavior and its effect on strengthening of an HSLA-Nb/Ti steel. Metall. Mater. Trans. A. 32 (7), 1635–1647 (2001).

Han, K. et al. Effects of vanadium addition on nucleation and growth of pearlite in high carbon steel. Mater. Sci. Eng. A. 10 (11), 955–963 (2013).

Jaiswal, S. & Mclvor, D. I. Metallurgy of vanadium-microalloyed, high-carbon steel rod. Mater. Sci. Tech-long. 1 (4), 276–284 (2013).

Solano-Alvarez, W., Gonzalez, F. & Bhadeshia, H. K. D. H. The effect of vanadium alloying on the wear resistance of pearlitic rails. Wear. ; 436–437(C):203004. (2019).

Mosher, D. R., Diercks, D. R. & Wert, C. A. Precipitation of carbon from solid solution in vanadium. Met. Mater. Trans. A. 3 (12), 3077–3080 (1972).

Katsuki, F. et al. Abrasive wear behavior of a pearlitic (0.4%C) steel microalloyed with vanadium. Wear 264 (3), 331–336 (2007).

Dunlop, G. L. et al. Precipitation of VC in ferrite and pearlite during direct transformation of a medium carbon microalloyed steel. Metall. Trans. A. 9, 261–266 (1978).

Dong, J. et al. Carbide precipitation in Nb-V-Ti microalloyed ultra-high strength steel during tempering. Mater. Sci. Eng. A. 683, 215–226 (2017).

Ioannidou, C. et al. Interaction of precipitation with austenite-to-ferrite phase transformation in vanadium micro-alloyed steels. Acta Mater. 181, 10–24 (2019).

Hansen, S. S., Sande, J. B. V. & Cohen, M. Niobium carbonitride precipitation and austenite recrystallization in hot-rolled microalloyed steels. Metall. Transa A. 11 (3), 387–402 (1980).

Maruyama, N. & Smith, G. D. W. Effect of nitrogen and carbon on the early stage of austenite recrystallisation in iron–niobium alloys. Mater. Sci. Eng. A. 327 (1), 34–39 (2002).

Hutchinson, C. R., Zurob, H. S., Sinclair, C. W. & Brechet, Y. J. M. The comparative effectiveness of Nb solute and NbC precipitates at impeding grain-boundary motion in Nb steels. Scr. Mater. 59, 635–637 (2008).

Takahashi, J. et al. Direct observation of Niobium segregation to dislocations in steel. Acta Mater. 107, 415–422 (2016).

Ray, A. Niobium microalloying in rail steels. Mater. Sci. Technol. 14, 1584–1600 (2017).

Dey, I., Saha, R. & Ghosh, S. K. Influence of microalloying and isothermal treatment on microstructure and mechanical properties of high carbon steel. Met. Mater. Inter. 28 (7), 1–16 (2021).

Zhang, S. C. et al. Design for improving corrosion resistance of duplex stainless steels by wrapping inclusions with Niobium armour. Nat. Commun. 14 (1), 7869–7869 (2023).

Han, K., Edmonds, V. D. & Smith, W. D. G. Optimization of mechanical properties of High-Carbon pearlitic steels with Si and V additions. Metall. Mater. Trans. A. 32 (6), 1313–1324 (2001).

Shi, G. H. et al. Microstructural evolution and mechanical properties of a low-carbon V–N–Ti steel processed with varied isothermal temperatures. Mater. Sci. Eng. A. 801, 140396 (2021).

Garbarz, B. & Pickering, B. F. Effect of austenite grain boundary mobility on hardenability of steels containing vanadium. Mater. Sci. Technol. 4 (11), 967–975 (2013).

Marder, A. R. & Bramfitt, B. L. The effect of morphology on the strength of pearlite. Metall. Trans. A. 7 (3), 365–372 (1976).

Walentek, A., Seefeldt, M., Verlinden, B., Aernoudt, E. & Van Houtte, P. Electron backscatter diffraction on pearlite structures in steel. J. Microsc. 224, 256–263 (2006).

Liu, P. C. et al. The significance of Nb interface segregation in governing pearlitic refinement in high carbon steels. Mater. Lett. 279, 128520 (2020).

Kuban, M. B. et al. An assessment of the additivity principle in predicting continuous-cooling austenite-to-pearlite transformation kinetics using isothermal transformation data. Metall. Mater. Trans. A. 17, 1493 (1986).

Li, Z. Y. et al. Evolution law of Anti-seismic rebars of 500 mpa grade under different cooling rates. J. Guizhou University(Natural Sciences). 37 (05), 61–66 (2020).

Pham, T. T., Hawblot, E. B. & Brimacombe, J. K. Predicting the onset of transformation under noncontinuous cooling conditions:part i.theory. Metall. Mater. Trans. A. 26 (8), 1987–1992 (1995).

Offerman, S. E. et al. In-situ study of pearlite nucleation and growth during isothermal austenite decomposition in nearly eutectoid steel. Acta Mater. 51 (13), 3927–3938 (2003).

Lee, K. J. Modelling of Γ/α transformation in niobium-containing microalloyed steels. Scripta Mater. 40 (7), 831–836 (1999).

Hillert, M. On the theory of normal and abnormal grain growth. Acta Metall. 13, 227–238 (1965).

Liu, J. et al. Effect of Ti and Nb microalloying on the microstructure of ultra pure 11% cr ferritic stainless steel. Acta Metall. Sin. 47 (06), 686–694 (2011).

Martin, G. & Rosenberg, G. Correlation between hardness and tensile properties in ultra-high strength dual phase steels-short communication. Mater. Eng. 18 (4), 155–159 (2012).

Yamamoto, K. et al. Influence of process conditions on microstructures and mechanical properties of T5-treated 357 aluminum alloys. J. Alloys Compd. 834, 155133 (2020).

Che, B. et al. Improving the mechanical properties of Ti-6554 alloy by tailoring dislocation density and multi-morphologic Αs phase via magnetic field[J]. Mater. Sci. Eng. A, 927148066–927148066. (2025).

Williamson, G. K. & Hall, W. H. X-ray line broadening from filed aluminium and Wolfram. Acta Metall. 1 (1), 22–31 (1953).

Gladman, T. Precipitation hardening in metals. Mater. Sci. Technol. 15, 30–36 (1999).

Yong, L. Second Phases in Steels (Metallurgical Industry, 2006).

Chen, J. H. & Cao, R. Micromechanism of cleavage fracture of metals: a comprehensive microphysical model for cleavage cracking in metals. (2014). https://doi.org/10.1016/C2013-0-18727-2

Sreenivasan Application of a cleavage fracture stress model for estimating the Astm e-1921 reference temperature of ferritic steels from instrumented impact test of Cvn specimens without precracking. Procedia Eng. 86, 272–280 (2014).

Alexander, D. J. & Bernstein, I. M. Cleavage fracture in pearlitic eutectoid steel. Metall. Trans. 20 (11), 2321–2335 (1989).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Nature Science Foundation of China (Grant no. 52464037).

Supported by Guizhou Provincial Program on Commercialization of Scientific and Technological Achievements Development and Application of Key Technology of Deep Drawn High Carbon Steel Coil for Tire Rim and Cord Wire and Special Wire Products(Grants No.QKHCG [2023]YB100))

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.H: Writing-original draft, Writing – review & editing, Formal Analysis; Methodology; C.R.L: Funding acquisition, Writing-review & editing, Methodology, Formal Analysis; Z.Y.L: Data curation; Z.Y.Z: Software, Resources; H.Y: Visualization; Y.J.S: Software, Validation.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Huang, S., Li, Z., Yang, H. et al. Effect of microalloying and isothermal transformation on the microstructure and mechanical properties of SWRH82B steel. Sci Rep 15, 10005 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-95103-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record: