Abstract

Soymilk, due to its high-quality protein and isoflavones content, is widely consumed worldwide. Unfortunately, soymilk lacks the powerful antioxidant vitamin E. Encapsulation of vitamin E and isoflavones in soymilk powder is advantageous for malnourished consumers to meet the recommendation. This study aimed to evaluate the impact of different encapsulation techniques and encapsulating materials on the storage stability and bioaccessibility of vitamin E and isoflavones in soymilk powder. Freeze-drying and spray-drying methods were applied with various encapsulating materials prepared from different ratios of maltodextrin to Acacia gum (100:0, 60:40, 50:50, 40:60, and 0:100). The results indicated that a 40:60 ratio of maltodextrin and Acacia gum provided the highest stability for 24 h of soymilk emulsion under the studied conditions. The shelf-life prediction of soymilk powder increased by more than two weeks when stored at 0 °C compared to the storage at ambient temperature. Spray-drying and freeze-drying techniques effectively encapsulate vitamin E and isoflavones within core microcapsules. Especially, freeze-drying process helps to prevent degradation during storage and allows for controlled release of the bioactive compounds during in-vitro digestion. Encapsulation efficiency of isoflavones and vitamin E for all formulation ranged from 80.9 ± 0.01% to 83.5 ± 0.20%, respectively. The highest vitamin E and isoflavones bioaccessibility of encapsulated product increased by up to 4.4-fold and 1.7-fold in the 60:40 formulations. Consuming 20 g of encapsulated vitamin E and 170 g of encapsulated isoflavones daily would be sufficient to meet the recommended intake.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Soybeans and their derivative products, such as soymilk, tofu, miso, and natto, have caught consumer’s attention due to their valuable micronutrient compositions. As a source of high-quality protein, vitamin D, and energy, soymilk, is affordable, readily available, and accessible to the estimated 795 million undernourished individuals in the 21st century1,2,3. Soymilk is free from lactose and cholesterol, making it suitable for lactose-intolerant. The chemoprotective effect and antioxidant properties are attributed to soy isoflavones, specifically daidzein and genistein. Additionally, consuming soy isoflavones may help prevent various diseases, such as hormonal disorders, several types of cancer (e.g., breast, prostate, and ovarian cancer), cardiovascular diseases, osteoporosis, and menopausal symptoms4,5,6. The requirement for isoflavones, expressed in aglycone equivalent weight, is approximately 40–50 mg per day7. In a clinical study, consuming 500 mL of soymilk twice a day for 3 months can lead to a decrease in blood pressure compared to consuming cow’s milk for adults with mild-to-moderate hypertension. In addition, the levels of serum d-dimer in type 2 diabetic patients with nephropathy also decreased with the consumption of soymilk8. Somehow, the metabolism of isoflavones is affected by the soymilk consumed, and the absorption rate of isoflavones in the human intestine is low because of its hydrophobic nature9.

Containing 400-fold lower amount in soymilk, the lipophilic vitamin E is 1.5-fold greater bioaccessible than isoflavones in soymilk-beverages10,11,12,13. The incorporation of external vitamin E in soymilk can be advantageous because of its antioxidant, anti-inflammatory properties, cholesterol-lowering and anticancer effect, protection against atherosclerosis and prevention of Alzheimer’s disease14,15. The recommended dietary allowance for vitamin E is 15 mg for both men and women aged 14 years and older16. To achieve a uniform distribution of vitamin E in soymilk, certain challenges need to be addressed, particularly the limited dispersion caused by the hydrophobic nature of vitamin E and the low-fat content of soymilk. A feasible solution involves using ultrasonication along with spray-drying or freeze-drying to create microencapsulated soymilk powder. This approach can effectively mask the undesirable bitterness of isoflavones, prolong the product’s shelf-life and ensure the stability of isoflavones and vitamin E release in the gastrointestinal tract17. Besides drying conditions, the composition and properties of feeding emulsions are crucial factors to consider in achieving the desired physicochemical characteristics of the final powdered products18.

Recently, the co-loaded emulsion of α-tocopherol and cholecalciferol in walnut oil was demonstrated to be stabilized by whey protein isolate and soy lecithin19. The ultrasonication at different pH was shown to improve the encapsulation efficiency of soybean lipophilic protein nano-emulsions for vitamin E20. Different types of wall materials such as polysaccharides (dextrin, pectin, Acacia gum and modified starches and their derivatives) and proteins (whey protein, gelatin, casein, milk serum, soy and wheat) determine the physicochemical properties, encapsulation efficiency and release behavior of isoflavones and vitamin E21,22,23,24,25,26. The encapsulation efficiency of isoflavones and its stability were improved by using the combination of Acacia gum (4, 6 and 8% w/v), 10% w/v of maltodextrin DE 18 and milk protein as wall materials for the spray-drying method24.

Available research data has focused on the improvement of isoflavones encapsulation in soymilk powder, using either spray-drying or freeze-drying techniques. However, there hasn’t been a comparative study on the simultaneous encapsulation of isoflavones and vitamin E in soymilk powder, nor has the in-vitro digestion of the latter been investigated.

The hypothesis is that the use of ultrasonication combined with spray-drying or freeze-drying for producing microencapsulated soymilk powder could be an effective strategy for enhancing the retention of vitamin E and isoflavones within the encapsulation material. This method may significantly improve the stability of these bioactive compounds, potentially reducing their degradation during storage and simulated gastrointestinal digestion. Therefore, the objectives of this study were to assess the effect of drying processes and wall materials composition on the encapsulation efficiency, physicochemical properties, storage stability and bioaccessibility of encapsulated vitamin E and isoflavones soymilk powder. To produce encapsulated vitamin E and isoflavones in soymilk powder, various wall material compositions containing maltodextrin and Acacia gum were used at different weight ratios. Thereafter, the emulsions were characterized and dried using freeze-drying or spray-drying techniques. The morphology of resulting soymilk powder from both drying techniques was evaluated using a scanning electron microscope (SEM). The stability of soymilk powder during storage was monitored through rancidity and antioxidant activity measurements. Additionally, the in-vitro digestion of the soymilk powder was conducted and the bioaccessibility of vitamin E and isoflavones was compared. The results of this study can help researchers identify the optimal wall composition for producing soymilk powder rich in vitamin E and isoflavones. This research may also enable the food industry to produce encapsulated soymilk powder, contributing to the fight against malnutrition in developing countries.

Materials and methods

Materials and chemicals

Soybeans were purchased from the local market, Prachinburi, Thailand. Acacia gum, food-grade encapsulating material, was purchased from Kemaus, New South Wales, Australia, and maltodextrin DE 18 was from Zhucheng dongxiao biotechnology Co.,Ltd, Dongxiao, China. Acetone and 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, Inc., St. Louis, USA. Tween80, ethanol, methanol, and hexane were from Macron Fine Chemicals, Sabah (Malaysia). Thiobarbituric acid was from Dalian Yoking Chemical Co.,Ltd, Liaoning, China.

Alpha-tocopherol (vitamin E) standard, solvents for high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), and enzymes (pepsin, pancreatin B1750 from porcine pancreas, bile extract porcine B8631) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich Chemie GmbH, Taufkirche, Germany. The other in-vitro digestion reagents and solvents were from Sigma-Aldrich Chemie GmbH, Taufkirche, Germany. The polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) membranes were obtained from Sartorius, Dourdan, France.

Soymilk Preparation process

Soymilk preparation method was adopted from Giri and Mangaraj27. Briefly, 1 kg of soybean of the same size and color, was dehulled and cleaned. Then, they were soaked in room temperature water containing 1% sodium bicarbonate at the volume ratio of soybean to water of 1:3 for 24 h to effectively inhibit the growth of micro-organisms. After that, soybeans were washed twice with clean water then wet ground with water 1 per 8 parts to obtain the slurry. Finally, the slurry was boiled for 5 min, then filtered through Muslin Cloth to separate residue (Okara) from soymilk.

The soymilk was separated into two batches and stored in an amber bottle at room temperature before further experiments. One batch was used for the preparation of soymilk emulsions and encapsulation. The other one was characterized in terms of color, pH, turbidity (WTW Turb® 550 turbidimeter, Berlin, Germany), dissolved solid fraction, the initial protein (Kjeldahl method) and lipid content (Soxhlet extraction method28).

Preparation of isoflavones and vitamin E emulsions

Oil-in-water emulsions were produced using soymilk previously prepared as an aqueous phase. Each encapsulating wall material (i.e., maltodextrin and Acacia gum) formula was prepared in a separate batch before dissolving in soymilk. After 1 h of the complete dissolution, 2 w/w% Tween80, a hydrophilic emulsifier, was added to the aqueous phase as well.

Stock soybean oil containing 50 w/w% of vitamin E was incorporated drop by drop into the aqueous phase to obtain the final formulation of 2 w/w% soybean oil and 2 w/w% vitamin E (α-tocopherol) and 20 w/w% encapsulating wall materials, Tween80 and 74 w/w% soymilk. Acacia gum was blended with maltodextrin and used as encapsulating wall material with the varied weight ratio of maltodextrin to Acacia gum at 100: 0, 0: 100, 40: 60, 50:50 and 60: 40. The coarse emulsions were produced using high-speed homogenization (Buono, Germany) at 16,000 rpm for 5 min. Fine emulsions were obtained by ultrasonication of the coarse emulsions with a stainless-steel ultrasound probe (13 mm diameter; QSonica, Newtown, CT, USA). Ultrasound homogenization was performed at 80% of the amplitude and 20 kHz of frequency at 60 °C for 15 min. The emulsions were evaluated in terms of emulsion droplet size and size distribution, zeta-potential, stability against phase separation and encapsulation efficiency after being transformed into soymilk powder.

Characterization of isoflavones and vitamin E emulsions

Zeta potential, particle size and size distribution

Zeta potential (ζ-potential), average particle size and size distribution of droplets were evaluated using dynamic light scattering (Zetasizer Nano ZS, Malvern Instruments Ltd., UK). Samples were diluted with deionized water and placed in a folded capillary cell for the measurement. Each sample was assayed in triplicate.

Creaming stability

Creaming index represents the emulsion stability against phase separation due to the creaming phenomenon. The centrifugal instability method was applied to determine the creaming index of samples. Emulsions (25 mL) were centrifuged at 2800 g for 15 min at 25 °C. The magnitude of the creaming phenomenon was determined after centrifugation by measuring the height of the cream upper layer (HC) and the height of the total emulsion (HT) in centimeters. Creaming index was then calculated using the following formula:

A low creaming index indicates a lesser extent of phase separation.

Fluorescence microscopy

Microscopic images of emulsions were established using a fluorescence microscope (Labovision, Ambala Cantt, India) equipped with a digital video camera. Samples were placed on a microscope slide and gently covered with a coverslip. The emulsion droplets were observed from five different fields on each slide with the objective at a magnification of 60x. Representative micrographs were then obtained.

Vitamin E and isoflavones encapsulated soymilk powder production

Freeze-drying process

The vitamin E and isoflavones emulsions were lyophilized using a freeze-dryer (LaboGene, CoolSafe 95/55–80 Touch Superior, Sweden). Samples were pre-freezed (Haier, DW-40L262, China) at −80 °C for 5 h. Main drying was carried out at −60 °C and 0.011 mbar for 24 h and final drying at −75 °C and 0.012 mbar for 1 h. Afterward, dried samples were carefully crushed into smaller carriers and sieved to obtain the homogeneous size. They were weighed and packed in a polyethylene bag and stored in a controlled moisture desiccator.

Spray-drying encapsulation

The vitamin E and isoflavones emulsions were spray dried (SDE-2 EURO2, India) using a peristaltic pump and atomized into small droplets by passing through a 0.7 mm nozzle diameter, 2000-ring nozzle in a co-current airflow system. The emulsions were fed at a flow rate of 10 mL/min and dried using an inlet air temperature of 180 °C and outlet air temperature of 90 °C, with an aspiration of 50 m3/h. The powder was collected, weighed, and sealed in a polyethylene bag, then stored in a controlled moisture desiccator before further analysis.

Characterization of vitamin E and isoflavones encapsulated soymilk powder

Moisture content and water activity

The moisture content of samples was determined after drying for 24 h at 105 °C. The water activity was determined using a water activity meter (Rotronic Hygrolab 3, USA). The measurements were carried out at 25 ± 2 °C in triplicate.

Color measurement and Browning index

The color of samples was evaluated based on L* (lightness), a* (redness, + or greenness, -) and b* (yellowness, + or blueness, -) values by using a Hunter Lab (USA). Browning index (BI) was determined according to Ruangchakpet and Sajjaanantakul29 using the following equation:

where

All samples were performed in triplicates.

Water solubility

The solubility of samples was determined according to the method of Şahin Nadeem et al.30 with some modifications. Approximately, 0.5 g of samples were added to 50 mL of distilled water at 25 °C and stirred at 800 rpm for 10 min until the homogeneous solution was obtained. The solution was then centrifuged at 3000 g for 5 min. An aliquot of 25 mL supernatant was transferred to pre-weighed Petri dishes and oven-dried at 105 °C for 24 h. The percent solubility was calculated by the difference in weight lost, multiplying by two for dilution and expressed in a dry basis. The measurement was done in triplicate.

Morphological analysis

The morphological and microstructural surface of samples were examined using a scanning electron microscope (SEM) (Axia ChemiSEM, USA). The sample was fixed to a double-sided adhesive carbon tape then coated with a fine layer of gold (15 mm). The observation was carried out in a high vacuum at an accelerator voltage of 10 kV. Digital images were captured at magnifications of 1500x and 2000x, respectively.

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR)

Samples were characterized by Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) to confirm the absence of chemical interactions between core and coated materials and to assess the formation of the microparticles. The FTIR spectra were recorded in a Thermo Nicolet iS5 FT-IR spectrometer equipped with an attenuated total reflectance unit (ATR) (Thermo Electron Corporation, Madison, WI, USA). The spectra were collected in triplicate in the region between 400 cm− 1 and 4000 cm− 1 with 26 accumulations. A previous air-background correction was considered. The spectra were standardized and analyzed by means using Origin software.

Isoflavones encapsulation efficiency

The encapsulation efficiency of isoflavones was calculated through the difference between the total and surface isoflavones of sample. The total and surface isoflavones encapsulated soymilk powder were determined by adapting the method from Rahman Mazumder and Ranganathan24, with minor modifications.

For total isoflavones content determination (TI), 10 mg of sample was dispersed in 50 mL of 96% ethanol. The dispersion was sonicated at the amplitude of ultrasound probe of 75 kHz, at 45 ºC for 20 min, then filtered through a glass filter. An aliquot from the filtrate was separated into 2 parts, one was mixed with 0.025 M potassium chloride buffer at pH 1.0 and another part of the filtrate was mixed with 0.4 M sodium acetate buffer at pH 4.5 to obtain the final volume of 10 mL for each pH value. Isoflavones were spectrophotometrically measured for absorbance at 262 and 660 nm. Whereby, 660 nm was absorbance for turbidity correction of a sample. Isoflavones content was calculated as a function of genistein using the following equation:

where, ∆A = (Abs262 at pH 1.0 - Abs660 at pH 1.0) - (Abs262 at pH 4.5 - Abs660 at pH 4.5); \(\:\epsilon\:\) (molecular extinction coefficient of genistein) = 35,842 L mol− 1 cm− 1 at 262 nm and 96% ethanol; l = path length in cm; MW (molecular weight of genistein) = 270.241 g/mol; DF = dilution factor.

For surface isoflavones content (SI) determination, 10 mg of sample was dispersed in 50 mL of 96% ethanol and vortexed for 2 min. The suspension was centrifuged at 2600 g for 5 min at 10 °C. Then, the supernatant was filtered through a 0.45 μm Millipore membrane, and the absorbance was spectrophotometrically measured using the same procedure as for determining the total isoflavones content.

The encapsulation efficiency of isoflavones was calculated to the following equation:

Vitamin E encapsulation efficiency

The encapsulation efficiency of vitamin E was calculated by the difference between the total and surface content of vitamin E. The total and surface vitamin E content of samples were analyzed by HPLC according to the method used by Mujica-Álvarez et al.31 with slight modifications. For total vitamin E content (TE) determination, 0.1 g of encapsulated powder sample was dispersed in 5 mL distilled water, then vortexed for 1 min. The mixture was transferred to a separation funnel then extracted with 6 mL hexane. After phase separation, the organic phase containing tocopherol was collected and dried under nitrogen flow. The residues were redissolved in 400 µL acetone and filtered through a PTFE membrane (0.45 μm) before HPLC injection. HPLC analysis was performed using a HPLC (Knauer, Germany) system equipped with a UV-visible photodiode array detector (Azura, Germany). The column was a polymeric C18 (4.6 mm i.d × 250 mm, 5 μm particle size, Vertex Plus Column). The mobile phase comprised two mixes (mix A and B) and the analysis was performed at a mobile phase flow rate of 1 mL/min. Mix A constituted of methanol and water, 60:40 (v/v), and mix B contained of methanol, methyl tert-butyl-ether and water, 28.5:67.5:4 (v/v/v). The gradient applied progressed from 100 to 0% (A/B) at 25 °C over a period of 31 min. Chromatograms were analyzed at the wavelength of maximum absorption of vitamin E isomer (i.e., α-tocopherol) at 298 nm. The concentration of extracted vitamin E was determined by the mean of external standard curve for vitamin E, which ranged in concentration from 0.5 to 25 mg/L.

For the determination of surface vitamin E content (SE), 0.1 g of sample was directly extracted with 2 mL ethanol/hexane (4:3 v/v) by vortex agitation for 30 s. Sample was then centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 10 min at 10 °C. Solution containing vitamin E was collected and dried under nitrogen flow. The residues were redissolved in 400 µL of acetone and filtered through a PTFE membrane (0.45 μm) before HPLC analysis using the same procedure as TE determination. Each sample was analyzed in triplicate.

The encapsulation efficiency of vitamin E was calculated using the following equation:

Determination of malondialdehyde content

Malondialdehyde (MDA) is the final adduct obtained from a lipid oxidation reaction. Sample (40 mg) was mixed with 2 mL of distilled water by vortex for 5 min. The aqueous dispersion was then mixed with 250 µL of thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS) (1w/v% in NaOH 50 mM) and 750 µL of H3PO4 (440 mM). The solution was vortexed for 3 min and then boiled for 60 min. The optical density of the mixture was measured at 533 nm using a UV-Vis spectrophotometer (Optima, SP-300, Japan). The concentration of MDA was determined by the mean of the calibration curve (0–10 µM) of tetraethoxypropane (TEP) which is naturally cleaved in MDA when dissolved in aqueous medium. Results were expressed in mg MDA/ kg of dried sample.

Antioxidant activity

The antioxidant activity of samples was evaluated using 2,2-diphenyl-1-picryl-hydrazyl (DPPH) assay. A methanolic solution of DPPH radicals (10− 4 mol/L) was freshly prepared before each experiment. Approximately, 40 mg of sample was transferred to a 10 mL volumetric flask and 1 mL of DPPH solution was added. The mixture was vortexed and kept in the dark for 30 min. The control solution was prepared by mixing 1 mL of DPPH solution with 6 mL of methanol. The absorbance was measured using a spectrophotometry at a wavelength of 515 nm. The free radical scavenger activity was calculated as the following equation.

where Ac is the absorbance of the control solution and As is the one of sample.

Accelerated shelf-life testing

Stability of encapsulated soymilk powder during storage was evaluated under accelerated shelf-life testing (ASLT) using the Q10 method. Q10 describes the increase in reaction rate for a 10 °C increase in temperature that negatively impacts the chemical composition, decrease the shelf-life of testing product32. Briefly, the encapsulated soymilk powder was packed in an individual aluminum foil sachet, then stored under two levels of accelerated temperature (35 and 45 °C). The shelf-life of vitamin E and isoflavones encapsulated soymilk powder was monitored until the product was rancid according to our preliminary experiment (malondialdehyde content greater than 3 mg MDA/ 100 g dried powder). The retention content of isoflavones and vitamin E, encapsulation efficiency, moisture content, water activity (aw), color, water solubility and free radical scavenging were analyzed every 24 h throughout storage for 9 days. Q10 of vitamin E and isoflavones encapsulated soymilk powder was calculated using the following equation:

where T1 and T2 represent storage temperatures at 35 °C and 45 °C, respectively. \({\theta}_{\left({T}_{1}\right)}\:\)and \({\theta}_{\left({T}_{2}\right)}\) are the times when vitamin E and isoflavones encapsulated soymilk powder stored at 35 °C and 45 °C reached the limiting malondialdehyde content.

In-vitro digestion of isoflavones and vitamin E

In-vitro digestion of encapsulated soymilk powder was performed according to the standardized INFOGEST protocol33. The digestive solutions comprise oral (Simulated Saliva Fluid, SSF), gastric (Simulated Gastric Fluid, SGF), and small intestinal (Simulated Duodenal Fluid, SDF) fluids which were prepared before the experiment. Sample was weighted (1 g) and placed into an amber screw-capped bottle. Then, 5 mL, pH 7.0 ± 0.2 SSF with mucin (3 mg/mL) were added and the sample was incubated for 2 min at 37 °C in a water bath under constant stirring at 100 rpm. Successively, 10 mL of SGF containing porcine gastric pepsin (2000 U/mL in the final digestion mixture) was added into the previous sample, the pH was adjusted to pH 3.0 ± 0.2 by adding 5 M HCl, and the sample was incubated again for 2 h at 37 °C under stirring. Finally, 20 mL SDF containing porcine pancreatin and bile salts (trypsin activity of 100 U/mL and lipase activity of 2000 U/mL in the final mixture) was added to the sample. The pH was adjusted to pH 7.0 ± 0.2 by adding 5 M NaOH, and samples were incubated for another 2 h at 37 °C under stirring. Digesta was centrifuged at 10,000 g for 30 min at 10 °C (Hettich, Rotana A35R, Germany). After the centrifugation, the supernatant from digesta was collected and filtered through a 0.2 μm cellulose acetate membrane to recover the micellar fraction. The micellar fractions containing isoflavones and vitamin E were then extracted and analyzed using HPLC, following the methods mentioned in sections “Isoflavones encapsulation efficiency” and “Vitamin E encapsulation efficiency”. The bioaccessibility of isoflavones and vitamin E corresponded to the ratio of the amount of each compound transferred to the micellar phase at the end of in-vitro digestion, relative to their initial contents before digestion.

Statistical analysis

All the experiments were performed in triplicate. Data were assessed by analysis of variance (one-way ANOVA) and Tukey’s test for post-hoc analysis using SPSS statistical software (Virginia, USA). Significance was accepted at P-value ≤ 0.05. The normality of distribution and equality of variances were verified using Kolmogorow-Smirnov test and Levene’s test, respectively.

Results and discussion

Initial soymilk characterization

The protein and oil content in soymilk have great importance in stabilizing emulsions. Due to their amphipathic properties, proteins play an emulsifying role in reducing the interfacial tension between water and oil through adhesion at the interfacial layer. Meanwhile, the fat content in soymilk facilitates the solubility of enriched vitamin E in soymilk-based emulsions. In this study, soymilk contained 2.99 w/v% of proteins and 2.09 w/v% of oil, consistent with the previously published data27. Its pH was around 6.5 and contained the total soluble solids of 6.3 °Brix. Soymilk was slightly yellowish (color value L* ≈ 40.85 ± 0.03, a* ≈ 0.63 ± 0.03 and b* ≈ 7.24 ± 0.01), turbid (3000 ± 1 NTU) and cloudier than coffee and tea (as supplementary material Fig. 1).

Emulsions characterization

Optical microscopic images of the vitamin E and isoflavones emulsions droplets stabilized by soymilk with and without addition of vitamin E (control formula) are shown in Fig. 1. Furthermore, the oil-in-water emulsions of vitamin E and isoflavones stabilized by soymilk were characterized as a function of particle size, zeta-potentials of oil droplets and creaming index (Table 1). The composition and amount of emulsifier Tween80 used in this study determined the droplet size of emulsions. In electrostatic stabilization, the surface charge of droplets or the zeta-potential value was usually measured as the charge of proteins adhering to the surface of oil droplets in an emulsion system. The higher the absolute zeta-potential value, the stronger the repulsion between droplets. The formulation without Acacia gum and maltodextrin had a spherical oil droplet dispersed in emulsion (fluorescent microscope at 60x), Fig. 1A. Experimentally, maltodextrin was completely soluble in soymilk. Soymilk emulsion contained solely maltodextrin as wall material was highly coalescent but better dispersed in oil droplets, Fig. 1B. When solely maltodextrin was used as wall material the complete dissolution of particles led to an increase in the solution’s density. Practically, maltodextrin is generally blended with other wall materials such as Acacia gum to create a better stabilization of emulsion34. In the present study, as shown in Table 1, the control formula and the vitamin E and isoflavones emulsions formulated with solely maltodextrin had the smallest particle size around 2.8 nm, considered as the microemulsions since the droplet diameter was less than 100 nm35. Contrariwise, when soymilk was stabilized with solely Acacia gum (AG), the spherical lipid droplet was observably more irregular and coalescent, Fig. 1C. The zeta-potential value of emulsions of vitamin E and isoflavones stabilized by soymilk was all negative and ranged from − 32.766 to −38.400 mV, Table 1. Assuredly, the surface of emulsion droplets was surrounded by anionic protein molecules36. The increase in Acacia gum ratio (40:60) led to an experimentally increase in viscosity from 250 cP (control) to 320 cP and oil droplet size, thus emulsion become more viscous in gel-like appearance, Fig. 1C-F. The complexation of two wall materials resulted in larger particle size, increasing up to 4-fold compared to the control, Table 1. Moreover, the maltodextrin and Acacia gum, might self-aggregate and increase in a size droplet. The result was consistent with Lv et al.37, who demonstrated that Acacia gum produced higher oil droplet size than quillaja saponin and whey protein isolate in vitamin E encapsulation within oil-in-water emulsions. Increasing in maltodextrin amount (MD: AG 40–60 to 60 − 40) led to a significantly increase in zeta-potential value, Table 1. Generally, the increase in an absolute zeta-potential values of -30 mV led to the disruption of the protein aggregates and prevented further aggregate formation38. However, the zeta-potential values of all samples seem to be enough to keep the oil droplets apart from each other. The high zeta-potential value increased emulsion’s stability against creaming. Obviously, the lowest phase separation or creaming index of 12.83 ± 0.49% was found, Table 1. In contrast, the control formula without an encapsulating wall exhibited the highest creaming index at 40.00 ± 1.61%. Increasing the maltodextrin content in MD: AG ratios of 40:60, 50:50, and 60:40 resulted in creaming indices of 12.83 ± 0.49%, 26.27 ± 1.04%, and 30.83 ± 0.61%, respectively.

The physical morphology (×60) of control soymilk emulsions (A) and soymilk emulsion with encapsulating materials containing solely maltodextrin (B); Solely Acacia gum (C), Maltodextrin and Acacia gum in ratio 40:60 (D), Maltodextrin and Acacia gum in ratio 50:50 (E) and Maltodextrin and Acacia gum in ratio 60:40 (F). ED: Emulsion droplet. Scale bars = 30 μm.

Physical property of encapsulated soymilk powder

The oil-in-water emulsions of vitamin E and isoflavones stabilized by soymilk at different MD: AG ratio were freeze-dried or spray-dried and the encapsulated soymilk powder was characterized as a function of moisture content, aw, and water solubility (Table 2). The moisture content of encapsulated soymilk powder after freeze-drying and spray-drying ranged from 7.53 to 1.92%, respectively. Spray-drying technique was more effective in lowering 3.3-fold the moisture content than the freeze-drying one. On the contrary, the water solubility of microencapsulated soymilk powder was statistically different for all formulation. The spray-dried microencapsulated soymilk powder showed better water solubility than the freeze-dried one after drying process. Sample coated with solely maltodextrin (MD 100) had the greatest water solubility (90%), Table 2. Increasing the Acacia gum ratio led to a decrease in water solubility. In a solid state, Acacia gum is harder soluble in water compared to maltodextrin. The lower moisture content in the product, the harder product is, thus a lower decrease in water solubility was observed. This phenomenon was clearly observed during the accelerated temperature of storage of spray-dried product compared to the freeze-dried one, Table 3. However, all formulation had an aw lower than 0.6 which clearly prevent the microorganism growth. All samples were bright (i.e., the L* value was positive). In contrast, increasing in the Acacia gum ratio led to a decrease in the a* value and b* value. The products were redder and more yellowish, especially the spray-dried samples. During spray-drying and freeze-drying, the Maillard reaction occurs, driven by reducing sugars and amino acids present in soymilk. During drying techniques, 5-hydroxymethylfurfural (HMF) can serve as markers in Maillard reaction. The final products of the Maillard reaction are melanoidins, responsible for the color, taste, flavor, and texture of soymilk powder. This non-enzymatic browning reaction might intensify the color of the spray-dried microencapsulated soymilk powder under a high temperature of 180 °C. However, a lower temperature of 5 °C did not have any effect on color formation during spray-drying of milk24.

Microstructure analysis

The drying techniques and encapsulating materials determined the morphology of encapsulated soymilk powder, Fig. 2. The freeze-dried encapsulated vitamin E and isoflavones soymilk powders had irregular form (FD1-5). The uneven shrinkage on the surface of encapsulated powder occurred due to the rapid water sublimation of the process. In contrast, the spray-dried samples were spherical or irregular shape (SD1-5). The smooth surfaces, pits and bumps were clearly observed. The rough surface of spray-dried sample might be caused by the collision of solid particles in the process as observed in the study of Jafari et al.39. In contrast, the smooth surface might be due to the maltodextrin high Dextrose Equivalent (DE) in encapsulating materials40. Our result was in accordance with Jafari et al.39, who demonstrated that the addition of maltodextrin resulted in spherical yogurt powder in spray-drying technique. The microcapsule is easily crusted during drying techniques41. Meanwhile, incorporating Acacia gum and modified starch led to shrinkage and unevenness in the shape and size of the sample.

The physical microstructure of control maltodextrin powder (MD), control Acacia gum powder (AG) and the one of the soymilk powders microencapsulated by freeze-drying (FD) and spray-drying (SD). The numbers (1–5) stand for the encapsulating materials 1: Solely maltodextrin, 2: Solely Acacia gum, 3: Maltodextrin and Acacia gum in ratio 40:60, 4: Maltodextrin and Acacia gum in ratio 50:50 and 5: Maltodextrin and Acacia gum in ratio 60:40. Scale bars = 50 μm.

During the food drying process, the loss of turgor pressure leads to significant changes in the microstructure of the food. This change results in color change and reduced surface gloss, and brightness, as shown in Table 3, making the product appear darker and less visually appealing. Additionally, shrinkage can decrease the product’s wettability, alter its texture, and limit its water solubility and ability to rehydrate effectively, Table 3. The microstructure of food plays a crucial role in the kinetics of nutrient release, absorption, and stability. The softening of this microstructure, by digestive enzymes, along with the denaturation of protein-bound nutrient complexes and the modification of swollen starch granules can enhance the bioaccessibility of the micronutrient in food product42.

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR)

The chemical functional group of encapsulating materials (MD-AG) and their possible interactions with the core vitamin E were assessed using FTIR, and the corresponding FTIR spectra of each sample are shown in Fig. 3. The absorption bands of AG were characterized at 1147 and 3285, corresponding to C-O stretching and -OH groups, respectively. While, the absorption bands of MD were 1015 (angular deformation of = CH and = CH2 bonds), 1149 (stretching vibrations of the C-C bonds in glucose rings), 1364 (aromatic ring vibrations) and 3285 (hydroxyl (–OH) groups). The absorption band at 1744 and 2922 were attributed to the ester carbonyl functional group of triglycerides and the C-H alkanes group of vitamin E, respectively43,44,45. Each encapsulating material and the core vitamin E were effectively separated by their respective chemical functional group spectra. No chemical interactions between the coating and core materials were observed during both drying processes (FD and SD).

The encapsulated soymilk powder formulated with MD: GA (40:60) of freeze-drying and spray-drying technique was physicochemically identified to have the lowest emulsion phase separation, water solubility (> 70%), desirable color shade (i.e., high value of L*, lower a* and b* value) and exhibited a good morphology. Therefore, this formula was selected to determine the shelf-life of the product under accelerated temperatures of storage.

Accelerated storage of encapsulated soymilk powder

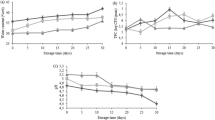

Various characteristics of the encapsulated soymilk powder formulated with MD: GA (40:60) were measured under accelerated storage temperatures of 35 °C and 45 °C, including vitamin E and isoflavones total and surface content, encapsulation efficiency, antioxidant activity and malondialdehyde content, solubility, total color change and browning index. The results are shown in Fig. 4; Table 3. The thermal and oxidative stability of the encapsulated vitamin E and isoflavones were improved by using wall materials24,46,47. Although, the chemical oxidation of the zero-order or first-order reaction throughout the exposure to the prolonged temperature and duration of storage was observed24. Figure 4A shows that the spray-dried encapsulated soymilk powder initially contained vitamin E 90 mg/100 g dry weight (DW) which was 1.5-fold higher than the freeze-dried one (60 mg/100 g DW). The surface vitamin E presented outside of the spray-dried encapsulated powder was of 18 mg while the one of freeze-dried encapsulated powder was of 12 mg/100 g DW (Fig. 4C). The vitamin E retention was drastically decreased up to 4-fold under 45 °C throughout 9 days of storage. Besides, the vitamin E encapsulation efficiency decreased from 80% to 20–55% at 45 °C depending on drying methods. The freeze-drying technique was more efficient for vitamin E encapsulation compared to spray-drying. The autoxidation of vitamin E in spray-dried nanocapsules through the wall materials has been reported47. The initial total isoflavones content and the surface isoflavones in microencapsulated soymilk powder varied from 93 to 156 mg/100 g DW and from 21 to 47 mg/100 g DW, respectively. The isoflavones encapsulation efficiency decreased from 80% to 20–69%. The freeze-dried and spray-dried encapsulated soymilk power may loss in wall physical property, consequently increasing moisture content and water activity leading to an increase in solubility in water. While, the isoflavones were stable and chemical reactions were inhibited when the aw was less than 0.348.

The total vitamin E content (A), total isoflavones content (B), surface vitamin E content (C), surface isoflavones content (D), vitamin E encapsulation efficiency (E), isoflavones encapsulation efficiency (F), antioxidant activity (G) and malondialdehyde content of soymilk powder (H) after freeze-drying (FD) and spray-drying (SD) at 35 °C and 45 °C of storage.

The decrease of microencapsulation efficiency can be compromised during storage through several mechanisms. Firstly, moisture absorption can lead to wall cracking, which increases gas permeability and exposes the core material to oxygen. Secondly, the encapsulating materials may undergo dissociation. Additionally, the solubility of the materials can diminish due to dehydration during storage, making the samples harder and more difficult to dissolve. Notably, samples stored at 45 °C showed a significant decrease in solubility, as well as increases in total color change (∆E) and browning index (BI), indicating a higher degree of degradation under these conditions (Table 3). These results could be related to the decreasing of vitamin E content in soymilk powder leading to a decrease in antioxidant activity against lipid oxidation. As expected, the antioxidant activity of soymilk powder decreased from 85% to 35–50% (Fig. 4G). The freeze-dried sample stored at 35 °C significantly showed the highest antioxidant activity, retained to 50% at the end of storage. The rancidity of lipids increased significantly up to 3.5 to 6 mg MDA/ kg at 45 °C during storage. The rancidity of tested soymilk powder in this study was perceived when the rancidity of lipid value was greater than 3 mg MDA/kg due to the oxidation over storage time of the oil body. Thus, the shelf-life prediction for encapsulated soymilk powder was based on the days when rancidity levels lower than 3 mg MDA/kg at 35 °C and 45 °C. For the spray-dried sample, the days used to calculate the Q10 formula were 7 and 2, while for the freeze-dried sample, they were 8 and 3, respectively. The shelf-life prediction of the spray-dried product at other temperatures of 30 °C, 20 °C, 10 °C and 0 °C was 13 days, 19 days, 25 days and 30 days, respectively. Whereas, it was 13 days, 20 days, 23 days and 24 days, respectively, for the freeze-dried one. Decreasing in temperature of storage could extend the shelf-life of the encapsulated soymilk power. Our results were in agreement with the previous studies which demonstrated that the chemical degradation of microencapsulation of isoflavones with milk24 or pepper seed oil by spray-drying technique43 using the combination of Acacia gum and maltodextrin was significantly prevented during storage period. However, accelerated conditions can indeed speed up certain deterioration processes, leading to unreliable results. Normal condition storage could be conducted simultaneously to validate the findings. To enhance the encapsulation efficiency of vitamin E and isoflavones in soymilk powder, it is vital to retain a significant amount of core materials. Incorporating appropriate other wall materials and binders can improve the stability of these bioactive compounds. Additionally, key drying parameters, including temperature, feed flow rate, airflow, and humidity, must be carefully optimized to enhance encapsulation efficiency and extend product shelf-life.

In-vitro digestion of encapsulated vitamin E and isoflavones soymilk powder

Five freeze-dried encapsulated vitamin E and isoflavones soymilk powder formulas were selected as the representative in-vitro digestion of the product due to its highest encapsulation efficiency of vitamin E and isoflavones content compared to the spray-dried one. Their bioaccessible content and relative bioaccessibility of vitamin E and isoflavones were compared (Fig. 5). In our study, the combination of encapsulating materials increased the relative vitamin E and isoflavones bioaccessibility up to 1.74 to 2.08-fold compared to the solely encapsulating materials used. The highest bioaccessible vitamin E content was 60.63 ± 1.07 mg/100 g DW and its relative bioaccessibility was 38.89 ± 0.79% in formula MD60:AG40, respectively. The formula MD60:AG40 exhibited the highest relative bioaccessibility of isoflavones at 87.26 ± 1.10%. This indicates that a lower amount of Acacia gum in the combined encapsulating materials leads to greater relative bioaccessibility of vitamin E and isoflavones. Generally, the vitamin E is unstable under an acidic digestion condition, thus its bioavailability is usually low. The vitamin E and isoflavones bioaccessibility was enhanced innovatively using microencapsulation release during simulated in-vitro digestion such as inulin and maltodextrin23, spiral dextrin inclusion complexes22 and Acacia gum, quillaja saponin and whey protein isolate in an emulsion system37. In our case, the complexation of maltodextrin and Acacia gum may protect the encapsulated vitamin E and isoflavones from drastic acidic conditions during in-vitro digestion resulting in the increase of vitamin E and isoflavone bioaccessibility. However, the increase in Acacia gum content up to a critical concentration led to a decrease in the relative vitamin E bioaccessibility. Indeed, an absorption of a fat-soluble vitamin E in the gastro-intestinal tract required mix-micelles incorporation. When the encapsulated soymilk powder dissolved in the digestive fluid, the maltodextrin was completely dissolved, whereas the Acacia gum - maltodextrin combination may interfere and avoid the formation of micelles, i.a., by increasing the viscosity of the digestive fluid. Thus, the relative vitamin E bioaccessibility decreased. Interestingly, the bioaccessibility of isoflavones was greater than vitamin E because the amount of lipophilic isoflavones aglycons form (daidzein and genistein) may be presented in a higher amount than micellarized lipophilic vitamin E in soymilk digesta fraction. Our results were consistent with those reported by Rodríguez-Roque et al.10 and Cilla et al.13. They have reported a higher bioaccessibility of isoflavones (35.40 − 47.32%) than the one of vitamin E (14.4%) in soymilk-based beverage and soy-based fruit beverages using high intensity pulsed electric fields processing, high-pressure processing and thermal processing respectively. Based on our study, consuming 20 g of microencapsulated vitamin E and 170 g of isoflavones soymilk powder a day could meet the recommendation for bioaccessible vitamin E and isoflavones. However, the recommended daily intake of isoflavones in soymilk may be perceived as excessive for regular consumption. Therefore, it is essential to explore methods for concentrating isoflavones in encapsulated soymilk powder to address this concern.

Conclusion

Soymilk is high in isoflavones but low in vitamin E content. However, isoflavones cause an undesirable bitter taste in natural soymilk, making it unacceptable for consumption. Both vitamin E and isoflavones are unstable under storage conditions and poorly absorbed in the human intestine. This research involved the microencapsulation of vitamin E and isoflavones in soymilk powder using ultrasonication followed by freeze-drying or spray-drying techniques. These processes demonstrated an increase in bioactive compound bioaccessibility and prolonged the shelf-life of the product. The use of a 40:60 ratio of maltodextrin to Acacia gum as encapsulating materials resulted in the highest encapsulation efficiency of isoflavones and vitamin E. However, increasing the Acacia gum content up to a certain amount decreased the bioaccessibility of encapsulated vitamin E and isoflavones. The shelf-life of microencapsulated soymilk powder was predicted to increase by more than two weeks when stored at 0 °C. Consuming 20 g of encapsulated vitamin E and 170 g of encapsulated isoflavones soymilk powder, respectively, a day could cover the recommended intake. Improving the bioaccessibility of encapsulated vitamin E and isoflavones in soymilk powder can enhance their bioavailability in humans. To ensure optimal bioaccessibility, several factors must be considered. These include digestion conditions such as digestion time, pH, the solid-liquid ratio, and the concentrations of digestive enzymes. Additionally, the diet types, food matrices, dietary components, and food processing methods also play a significant role. This research may be strategically useful in selecting an appropriate ratio of encapsulating materials and storage conditions to better preserve and deliver vitamin E and isoflavones, addressing malnutrition.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Begum, A. & Mazumder Md. A. Soymilk as source of nutrient for malnourished population of developing country: A review. (2016).

Webb, P. et al. Hunger and malnutrition in the 21st century. BMJ 361, k2238 (2018).

Rotundo, J. L. et al. European soybean to benefit people and the environment. Sci. Rep. 14, 7612 (2024).

Jou, H. J. et al. Effect of intestinal production of equol on menopausal symptoms in women treated with soy isoflavones. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 102, 44–49 (2008).

Křížová, L., Dadáková, K., Kašparovská, J. & Kašparovský, T. Isoflavones Mol. 24, 1076 (2019).

Islam, A., Islam, M. S., Uddin, M. N., Hasan, M. M. I. & Akanda, M. R. The potential health benefits of the isoflavone glycoside genistin. Arch. Pharm. Res. 43, 395–408 (2020).

Chen, L. R., Ko, N. Y. & Chen, K. H. Isoflavone supplements for menopausal women: A systematic review. Nutrients 11, 2649 (2019).

Miraghajani, M. S., Esmaillzadeh, A., Najafabadi, M. M., Mirlohi, M. & Azadbakht, L. Soy milk consumption, inflammation, coagulation, and oxidative stress among type 2 diabetic patients with nephropathy. Diabetes Care. 35, 1981–1985 (2012).

Kano, M., Takayanagi, T., Harada, K., Sawada, S. & Ishikawa, F. Bioavailability of isoflavones after ingestion of soy beverages in healthy adults. J. Nutr. 136, 2291–2296 (2006).

Rodríguez-Roque, M. J. et al. In vitro bioaccessibility of isoflavones from a soymilk-based beverage as affected by thermal and non-thermal processing. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 66, 102504 (2020).

Zhang, Y. et al. Intestinal absorption of prenylated isoflavones, Glyceollins, in Sprague–Dawley rats. J. Agric. Food Chem. 68, 8205–8211 (2020).

Andlauer, W., Kolb, J. & Fürst, P. Absorption and metabolism of genistin in the isolated rat small intestine. FEBS Lett. 475, 127–130 (2000).

Cilla, A. et al. Bioaccessibility of tocopherols, carotenoids, and ascorbic acid from Milk- and Soy-Based fruit beverages: influence of food matrix and processing. J. Agric. Food Chem. 60, 7282–7290 (2012).

Galli, F. et al. Emerging aspects and new directions. Free Radic Biol. Med. 102, 16–36 (2017). Vitamin E.

Lloret, A., Esteve, D., Monllor, P., Cervera-Ferri, A. & Lloret, A. The effectiveness of vitamin E treatment in Alzheimer’s disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20, 879 (2019).

Rizvi, S. et al. The role of vitamin E in human health and some diseases. Sultan Qaboos Univ. Med. J. 14, e157–e165 (2014).

Roland, W. S. U. et al. Soy isoflavones and other isoflavonoids activate the human bitter taste receptors hTAS2R14 and hTAS2R39. J. Agric. Food Chem. 59, 11764–11771 (2011).

Jafari, S. M., Arpagaus, C., Cerqueira, M. A. & Samborska, K. Nano spray drying of food ingredients; Materials, processing and applications. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 109, 632–646 (2021).

Kim, Y. J. et al. Cholecalciferol- and α-tocopherol-loaded walnut oil emulsions stabilized by Whey protein isolate and soy lecithin for food applications. J. Sci. Food Agric. 102, 5738–5749 (2022).

Wang, D. et al. Effects of pH on ultrasonic-modified soybean lipophilic protein nanoemulsions with encapsulated vitamin E. LWT 144, 111240 (2021).

Sansone, F. et al. Enhanced technological and permeation properties of a microencapsulated soy isoflavones extract. J. Food Eng. 115, 298–305 (2013).

Wang, P. P., Luo, Z. G. & Peng, X. C. Encapsulation of vitamin E and soy isoflavone using spiral dextrin: comparative structural characterization, release kinetics, and antioxidant capacity during simulated Gastrointestinal tract. J. Agric. Food Chem. 66, 10598–10607 (2018).

Wyspiańska, D., Kucharska, A. Z., Sokół-Łętowska, A. & Kolniak‐Ostek, J. Effect of microencapsulation on concentration of isoflavones during simulated in vitro digestion of isotonic drink. Food Sci. Nutr. 7, 805–816 (2019).

Rahman Mazumder, Md, A. & Ranganathan, T. V. Encapsulation of isoflavone with milk, maltodextrin and gum acacia improves its stability. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2, 77–83 (2020).

Chao, P. W., Yang, K. M., Chiang, Y. C. & Chiang, P. Y. The formulation and the release of low–methoxyl pectin liquid-core beads containing an emulsion of soybean isoflavones. Food Hydrocoll. 130, 107722 (2022).

Liu, Q., Sun, Y., Cheng, J. & Guo, M. Development of Whey protein nanoparticles as carriers to deliver soy isoflavones. LWT 155, 112953 (2022).

Giri, S. K. & Mangaraj, S. Processing influences on composition and quality attributes of soymilk and its powder. Food Eng. Rev. 3, 149–164 (2012).

Horwitz, W. Official Methods of Analysis of AOAC International. Volume I, Agricultural Chemicals, Contaminants, Drugs / Edited by William Horwitz. (AOAC International, 2010). (1997).

Ruangchakpet, A. & Sajjaanantakul, T. Effect of Browning on total phenolic, flavonoid content and antioxidant activity in Indian gooseberry (Phyllanthus emblica Linn). Agric. Nat. Resour. 41, 331–337 (2007).

Şahin Nadeem, H., Torun, M. & Özdemir, F. Spray drying of the mountain tea (Sideritis stricta) water extract by using different hydrocolloid carriers. LWT - Food Sci. Technol. 44, 1626–1635 (2011).

Mujica-Álvarez, J. et al. Encapsulation of vitamins A and E as spray-dried additives for the feed industry. Molecules 25(6), 1357 (2020).

Fu, B. & Labuza, T. P. Shelf-life prediction: theory and application. Food Control. 4, 125–133 (1993).

Minekus, M. et al. A standardised static in vitro digestion method suitable for food – an international consensus. Food Funct. 5, 1113–1124 (2014).

Patel, S. & Goyal, A. Applications of natural polymer gum Arabic: A review. Int. J. Food Prop. 18, 986–998 (2015).

McClements, D. J. Nanoemulsions versus microemulsions: terminology, differences, and similarities. Soft Matter. 8, 1719–1729 (2012).

Matsumiya, K., Takahashi, W., Inoue, T. & Matsumura, Y. Effects of bacteriostatic emulsifiers on stability of milk-based emulsions. J. Food Eng. 96, 185–191 (2010).

Lv, S., Zhang, Y., Tan, H., Zhang, R. & McClements, D. J. Vitamin E encapsulation within oil-in-water emulsions: impact of emulsifier type on physicochemical stability and bioaccessibility. J. Agric. Food Chem. 67, 1521–1529 (2019).

Shanmugam, A. & Ashokkumar, M. Ultrasonic preparation of stable flax seed oil emulsions in dairy systems – physicochemical characterization. Food Hydrocoll. 39, 151–162 (2014).

Jafari, S. M., Vakili, S. & Dehnad, D. Production of a functional yogurt powder fortified with nanoliposomal vitamin D through spray drying. Food Bioprocess. Technol. 12, 1220–1231 (2019).

Abd Ghani, A. et al. Effect of different dextrose equivalents of maltodextrin on oxidation stability in encapsulated fish oil by spray drying. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 81, 705–711 (2017).

Xiao, Z., Xia, J., Zhao, Q., Niu, Y. & Zhao, D. Maltodextrin as wall material for microcapsules: A review. Carbohydr. Polym. 298, 120113 (2022).

Karim, M. A., Rahman, M. M., Pham, N. D. & Fawzia, S. Food Microstructure as affected by processing and its effect on quality and stability. in Food Microstructure and Its Relationship with Quality and Stability (ed. Devahastin, S.) 43–57 (Woodhead Publishing, 2018).

Karaaslan, M. et al. Gum Arabic/maltodextrin microencapsulation confers peroxidation stability and antimicrobial ability to pepper seed oil. Food Chem. 337, 127748 (2021).

Lei, M. et al. Facile microencapsulation of Olive oil in porous starch granules: fabrication, characterization, and oxidative stability. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 111, 755–761 (2018).

Fathi, M., Nasrabadi, M. N. & Varshosaz, J. Characteristics of vitamin E-loaded nanofibres from dextran. Int. J. Food Prop. 20, 2665–2674 (2017).

Zhu, J. et al. Preparation of spray-dried soybean oil body microcapsules using maltodextrin: effects of dextrose equivalence. LWT 154, 112874 (2022).

Hategekimana, J., Masamba, K. G., Ma, J. & Zhong, F. Encapsulation of vitamin E: Effect of physicochemical properties of wall material on retention and stability. Carbohydr. Polym. 124, 172–179 (2015).

Mazumder, M. A. The roles of genistein as anti-browning agent in liquid and powdered emulsions. (2016).

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by King Mongkut’s University of Technology North Bangkok, Contract no. KMUTNB-66-KNOW-12. The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Pakkawat Detchewa: Writing - original draft; Conceptualization; Methodology; Software; Formal analysis; Investigation; Validation; Visualization. Chutima Aphibanthammakit: Methodology; Investigation; Formal analysis; review & editing. Anuchita Moongngarm : Visualization; Supervision; Writing - review & editing.Sylvie Avallone : Visualization; Supervision; Methodology; Writing - review & editing.Patcharee Prasajak: Investigation; Methodology; Formal analysis.Chadaporn Boonpan: Perform experiments; Investigation.Varathip Ruangdath: Perform experiments; Investigation.Wichien Sriwichai: Funding acquisition; Methodology; Writing - review & editing; Supervision; Conceptualization; Validation; Project administration; Resources; Software; Data curation.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Detchewa, P., Aphibanthammakit, C., Moongngarm, A. et al. Microencapsulation techniques and encapsulating materials influenced the shelf life and digestion release of vitamin E and isoflavones in soymilk powder. Sci Rep 15, 10627 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-95284-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-95284-4