Abstract

In order to address the problem of coordinated flood forecasting in the urbanized watershed, this study proposes a framework for discriminating easily occurring runoff component, which considers vertical spatial heterogeneity based on soil type, land use type and topographic slope, and integrates a Grid-based Runoff Generation Model (GRGM). Taking the control watershed of Jialu River at Zhongmou station (including the central city of Zhengzhou) as the study area, on the basis of GRGM model tests based on 11 observed rainfall-runoff events, the spatial and temporal evolution of runoff components in the study area from 1980 to 2020 and their correlation with the underlying surface changes are explored. The study reveals that: (a) the average relative error of the runoff generation calculation by GRGM model in the study area is reduced by 27.76% and the average coefficient of determination is increased by 0.11 compared with Horton Infiltration (HI) model, which means GRGM model are more accurate. (b) The percentage of excess surface runoff (Rs) in the central city increased significantly from 22 to 67%, and showed a trend of expansion from the central city to the suburbs. (c) The land use types have changed significantly, mainly manifested as a substantial reduction of cropland and a sharp expansion of construction land. Rs is significantly positively correlated with construction land, and the Pearson correlation coefficient exceeds 0.93. The study findings can serve as a scientific basis for coordinated management of flood prevention and disaster reduction in the urbanized watershed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Global population growth and accelerated urbanization have significantly altered the underlying surface of watersheds, which in turn has led to profound changes in hydrological processes1,2,3. The expansion of impervious surfaces reduces infiltration capacity, increases surface runoff, and disrupts the hydrologic balance of the whole watershed4,5. Cities are mostly located within watersheds, and their hydrological dynamics are closely interdependent with those of the watersheds6. Therefore, understanding the specific effect of underlying surface changes on runoff is essential for the effective sustainable management of water resources in watershed-urban complex system7,8.

The underlying surface can affect runoff through features including land use types, soil types, and topographic slopes. Land use change affects runoff by directly altering surface characteristics. Moniruzzaman et al. found that increased impervious surfaces significantly enhanced surface runoff, especially in urban area9. Guo et al. concluded that decreases in forest cover and increases in grassland area combine to lead to higher runoff7. In addition, several studies have shown that soil type and topographic slope also play a key role in runoff generation by influencing infiltration and runoff routes10,11. The above studies are limited to the effect of a single underlying surface feature on runoff, ignoring the synergistic effect of multiple underlying surface features on runoff components.

Currently, distributed hydrological models are widely used to simulate runoff processes, but they usually rely on runoff data at the outlet of a watershed, which makes it difficult to provide details of the spatial distribution of runoff12,13,14. Therefore, it is crucial to construct a model based on the spatial heterogeneity of runoff components for runoff generation calculation. Most recent studies have focused on dividing the three runoff generation patterns through underlying surface features and constructing a semi-distributed model, but have not further divided the runoff components15,16. In fact, runoff components can be categorized into four types: excess surface runoff (Rs), saturated surface runoff (Rsat), interflow runoff (Rint), and groundwater runoff (Rg), and underlying surface changes can significantly affect the spatial pattern of runoff components17,18. Previous studies have successfully discriminated saturated overland flow, subsurface flow and deep percolation by using geologic information and soil properties data19,20,21. However, the distributed runoff calculation and the discrimination of runoff components have not yet been organically integrated. The changing characteristics of runoff components and their correlation with land use changes have also not been adequately explored for urbanized watersheds.

Therefore, this study focuses on the vertical spatial conductivity effect of underlying surface factors on the runoff generation process, and proposes a framework for discriminating the easily occurring runoff component based on “soil type-land use-topographic slope”, and integrates a Grid-based Runoff Generation Model (GRGM). Taking the control watershed of Jialu River at Zhongmou station (including the central city of Zhengzhou) as the study area, the spatial and temporal evolution of runoff components are analyzed on the basis of runoff generation calculation using the GRGM model, and the correlation analysis between the runoff components and the land use types is conducted, with a view to better predicting and responding to hydrological problems that may arise in the process of urbanization in watershed-urban complex system.

Methods

A framework for discriminating the easily occurring runoff component

The discrimination of the dominant runoff components varies depending on the discriminating factors, and in this paper, the discrimination is mainly through the underlying surface factors. The three underlying surface factors act synergistically in the process of water infiltration, thus significantly affecting regional runoff. Different soil types have different particle compositions, which have a direct effect on water permeability and infiltration rates. Larger soil particles have better permeability and faster infiltration rates, and are therefore more likely to produce interflow runoff and groundwater runoff; conversely, smaller soil particles have poorer permeability and slower infiltration rates, and are more likely to produce Rs and Rsat22. According to the International standard for soil type classification, the particle size composition of the four soil types in the study area is shown in Table 123. Land use types also have a significant impact on water infiltration due to differences in land cover24. Cropland usually has a low land cover and human activities have changed the texture and composition of the soil to a certain extent, which in turn reduces its infiltration capacity. Forests and grasslands with well-developed root systems of vegetation are more conducive to the infiltration of water. Construction land has a large amount of impervious surfaces, which severely impedes the infiltration process of water. And water do not need to be infiltrated, so rainfall that falls on the water can be considered to directly produce Rs. The topographical slope is a key factor that dominates the flow pattern, and steeper areas have faster water flow rates, often resulting in the loss of water before it can sufficiently infiltrate, and therefore are more prone to surface runoff than flat areas25,26. According to the permeability and vertical spatial conductivity of the three factors above, a framework for discriminating easily occurring runoff component based on “soil-land use-slope” is established. The ArcMap 10.7 software is used to divide the grid with an accuracy of 30 × 30 m, and the most easily occurring runoff component on each grid are identified by this method. The specific framework is shown in Fig. 1.

The Grid-based runoff generation model

Runoff generation is mainly controlled by two conditions: the rainfall intensity (i) exceeding the infiltration capacity (fp) and the soil water content exceeding the field capacity in the vadose zone16. It is first assumed that I is the total amount of rainfall entering the vadose zone, E is the evapotranspiration, and D is the water deficit in the vadose zone. When i < fp and I-E ≤ D, no runoff occurs. When i > fp and I-E ≤ D, the soil is unable to absorb and store the rainfall quickly, and there is a sharp, thin, and symmetrical line of flooding processes from the surface runoff in the river. When i ≤ fp and I-E > D, there is a short, fat, and symmetrical line of flooding processes from the groundwater runoff. And when i > fp and I-E > D, there is an obviously asymmetrical line from both the surface runoff and the groundwater runoff. Based on this, the grid-based runoff generation model (GRGM) is integrated to calculate four types of runoff components based on different underlying surface factors, which in turn determines the runoff generation process of grid cells. The generation of the four runoff components is calculated as follows:

The integral for the runoff is calculated as follows:

The total amount of runoff is calculated as follows:

In which Rs is excess surface runoff depth (mm), fp is infiltration capacity of the upper soil (mm/h), i is rainfall intensity (mm/h), t is rainfall period (h), Rsat is saturated surface runoff depth (mm), rint is interflow runoff intensity (mm/h), Rint is interflow runoff depth (mm), fcA is stable infiltration rate of the upper soil (mm/h), fcB is stable infiltration rate of the lower soil (mm/h), Rg is groundwater runoff depth (mm), and fc is stable infiltration rate of vadose zone (mm/h).

Evaluating the simulation results of each calibration or validation process is crucial. Relative error (RER) and coefficient of determination (\(R_{R}^{2}\)) of runoff depth are selected to evaluate the accuracy of GRGM model. They are calculated as follows:

In which m is the number of runoff events, Rsi, Ro is simulated runoff and observed runoff, mm, respectively, and \(\overline {{{R_{si}}}}\), \(\overline {{{R_o}}}\) is average simulated runoff and average observed runoff, mm, respectively. RER reflects the deviation of simulated runoff depth from observed runoff depth, and the smaller the value is, the closer the model calculation results are to the actual observation. In order to meet the accuracy requirements of runoff depth forecasting, it is necessary to ensure that the RER is within 20%27. \(R_{R}^{2}\) is used to assess how well the model fits the observed data and it lies between [0, 1], with values closer to 1 indicating that the model fits the data better.

Horton infiltration model

In the 1930s, hydrologist Horton proposed an infiltration model: when the rainfall intensity is less than or equal to the infiltration capacity, rainfall infiltrates into the ground to supply the soil water deficit; when rainfall intensity is more than the infiltration capacity, rainfall infiltrates according to the infiltration capacity, and the extra rainfall generates Rs28. The formula for Rs in Horton infiltration (HI) model is the same as the formula (5) above as the principle of calculating Rs in the GRGM model is consistent with HI model.

The transfer matrix

The transfer matrix is widely used in the analysis of spatial property changes, which can quantify the transfer of states and conditions within a system, and its theoretical basis originates from the field of system analysis29. In this study, the transfer matrix is used to effectively quantify the dynamic evolution of various types of land use and runoff components in the study area from the beginning to the end of a specific time period, which is of great significance for recognizing the influence of changes in the underlying surface on the runoff30,31. Its mathematical expression is as follows32:

In which Sij is the area of the initial class i property transferred to the final class j property. ΣSij is the area of the study area, which is equal to the sum of all the elements in the matrix. ΣSij minus the sum of the diagonal elements ΣSii is the amount of transfer, and the amount of transfer out is equal to the amount of transfer in.

Pearson correlation coefficient

Pearson correlation analysis is a statistical test for a possible two-way linear correlation between two variables33. Pearson correlation coefficient is used to quantify the degree of correlation between two variables and is distributed in the interval [-1, 1], with positive coefficients indicating positive correlation, negative indicating negative correlation, and 0 indicating irrelevant. The closer the absolute value of the coefficient is to 1, the greater the degree of correlation, and equal to 1 is perfect correlation34. It is calculated as follows:

In which γ is Pearson correlation coefficient, Xh, Yh is the runoff components and land use types in the hth year, respectively, and \(\bar {X}\), \(\bar {Y}\) is the mean of the runoff component data series and the mean of the land use type data series, respectively.

Case study

Study area

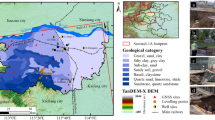

The control watershed of Jialu River at Zhongmou station is selected as the study area, with an area of 2106 km2. The watershed contains the central city of Zhengzhou composed of Jingshui District, Erqi District, Zhongyuan District, Huiji District and Guancheng District, with an area of 1010 km2, accounting for 48% of the watershed. The watershed’s terrain is mainly plain, with a northern temperate continental monsoon climate, frequent alternation of warm and cold air masses, and an average annual temperature of 14.3 °C. Zhengzhou is located in the central part of Henan Province, China, which is the capital city of Henan Province, one of the fifteen national cities in China, and also an important transportation hub in China35. As of 2020, the urbanization rate of Zhengzhou has reached 78.4%. In 2021, the flood disaster caused by “7·20” heavy rainstorm in Zhengzhou had obvious “external flooding - internal waterlogging” superposition characteristics, which caused widely affected area and heavy economic losses, and it is extremely rare in the history of natural disasters in China17. Therefore, the control watershed at Zhongmou station as the study area can satisfy the demand for example test of the universality of the GRGM model runoff calculation. Figure 2 shows a map of the study area, which is created using ArcMap 10.7 software.

Geographic location of the control watershed of Jialu River at Zhongmou station (The boundary of Zhengzhou city is sourced from https://dnr.henan.gov.cn/, and the watershed is extracted by the “Hydrological analysis” function in ArcMap 10.7 software downloaded from https://www.esri.com/zh-cn/arcgis/products/arcgis-desktop/overview).

Rainfall-runoff data collection and processing

The rainfall data and runoff data in the control watershed of Jialu River at Zhongmou station are derived from the Hydrological Yearbook of Henan Province, and considering the completeness and representativeness of the rainfall-runoff events, 11 events with peak discharge greater than 35 m³/s from 2016 to 2019 are selected. As shown in Fig. 3, the durations of the runoff events ranged from 49 to 97 h, and runoff depths ranged from 2.94 to 7.69 mm. Among them, 6 rainfall-runoff events are used for GRGM model parameter rate calibration, and 5 events are used for validation. The runoff data originated from Zhongmou hydrological station, and the rainfall data originated from 37 rainfall stations in the study area, with a uniform interpolation of 1 h intervals.

Underlying surface data processing

The soil type data are derived from Resource and Environmental Science Data Platform of Chinese Academy of Sciences (https://www.resdc.cn/), with an accuracy of 30 m×30 m. The main soil types in the study area are classified into four categories: loam, silt loam, sandy loam and loamy sand. The satellite remote sensing images are adopted from Landsat series with an accuracy of 30 m×30 m, and the land use data are interpreted by ENVI 5.6 software. The land use types in the study area are divided into five categories: cropland, construction land, water, forest, and grassland. 100 decoded image elements of each type are randomly selected for visual comparison, and the number of correctly classified image elements is 473, with an overall classification accuracy of 94.6%. The digital elevation model (DEM) is derived from Geospatial Data Cloud (https://www.gscloud.cn/), with a spatial accuracy of 30 m×30 m. The slope distribution is extracted from the DEM by ArcMap 10.7 software, and is divided into three intervals of 0–5°, 5–15° and > 15°. The distribution of soil types, land use types and topographic slopes in the study area is shown in Fig. 4. Land use changes are analyzed in detail in Section “Correlation analysis between runoff components and landuse types”, and Fig. 4c only shows the distribution of land use types in 2020. Using the spatial layer property “Reclassify” function in ArcMap 10.7 software, the loamy sand, sandy loam and silt loam, and loam in the soil type layer are numbered 1, 2 and 3, respectively; the cropland, forest, grassland, water and construction land in the land use layer are numbered 1–5, respectively; and the 0–5°, 5–15° and > 15° in the slope layer are likewise numbered 1, 2 and 3, respectively. Prior to reclassification, the data layers are image-scale aligned and corrected using the “Resample” function to ensure data accuracy and consistency. Then use “Raster Calculator” function according to the feature formula “soil type × 100 + land use type × 10 + slope × 1” for the second calculation of spatial conductivity properties to get the feature number. For example, the soil type, land use and slope in a grid are loamy sand, cropland and 20°, respectively, corresponding to reclassification values of 1, 1 and 3, respectively, and a grid property of 113 after raster superposition computation by the feature formula. According to the easily occurring runoff component discrimination framework, the runoff component corresponding to this grid is Rs.

Spatial distribution of underlying surface factors (The figures are created in ArcMap 10.7 software downloaded from https://www.esri.com/zh-cn/arcgis/products/arcgis-desktop/overview).

Results and discussions

Validation of the results of runoff generation calculation

The results of runoff generation calculation of GRGM model and HI model are shown in Fig. 5a and b. The average \(R_{R}^{2}\) of GRGM model is 0.96, whereas of the HI model it is only 0.85. The average RER of GRGM model and HI model are 9.28% and 37.04%, respectively. Among them, GRGM model has 8 rainfall-runoff events with RER within 10% and the remaining 3 events have RER in the range of 10–20%. The average of RER runoff generation calculation by GRGM model in the study area is reduced by 27.76% and the average \(R_{R}^{2}\) is increased by 0.11 compared with HI model, which means GRGM model are more accurate.

In Fig. 5b, the RER of GRGM in the seventh rainfall-runoff event (20170819) is higher than that of HI, which may be attributed to several reasons. Firstly, the GRGM model relies on high-precision underlying surface data, and there may have been temporary updates to the underlying surface data at the time of this event that were not recognized by the model. Secondly, the rainfall pattern of this event is unique, with a small amount of rainfall in the early period and a long rainfall duration, which differed from the calibration data, and the model may have generated errors due to the lack of generalization ability. Finally, the computational complexity of the GRGM model may also lead to a decrease in model accuracy. Conversely, the HI model has a simple structure and is less affected by uncertain events, and therefore may simulate the runoff that conform to its pattern with less error.

Characterization of the spatial and temporal distribution of runoff components and their evolution

Figure 6 shows the spatial distribution of runoff components in the watershed. During the past four decades, Rs is mainly concentrated in the center of the study area and gradually expanded from the center to the surroundings. Rsat is mainly located in the southwest of the study area. Rint and Rg are evenly distributed around the study area and are gradually replaced by Rs. By 2020, the distribution of runoff in each district of the central city has shown distinct spatial heterogeneity. As the core area of urban development, the dominance of Rs in Jinshui, Zhongyuan and Guancheng districts is significant. In contrast, Rsat is very scarce in the central city. The distribution of runoff components in Erqi and Huiji districts is relatively balanced. The unevenness in the spatial distribution of runoff components not only reflects the unevenness in the changes of the underlying surface, but also further reveals the unevenness in regional development.

Spatial distribution of runoff components in the study area from 1980 to 2020 (The figures are created in ArcMap 10.7 software downloaded from https://www.esri.com/zh-cn/arcgis/products/arcgis-desktop/overview).

Figure 7 illustrates the change in the percentage of runoff components. During 1980 to 2020, the percentage of Rs in the central city increased significantly from 22 to 67%, and the Rs in the watershed, although also experiencing an increase, is much less than that in the central city. The percentage of Rsat has been maintained at a low level for a long time. Rint and Rg have similar trends, with the percentage of Rg being slightly higher than that of Rint. During the decade of rapid acceleration of urbanization from 2000 to 2010, its underlying surface conditions changed greatly, and the proportion of the four runoff components changed most drastically during this period. During this decade, the percentage of Rs in the watershed increased rapidly from 24 to 41%, while the other three runoff components showed a decreasing trend. This time period coincides with the stage of rapid urbanization.

Figure 8 represents the dynamic evolution of each runoff component in the central city from 1980 to 2020. There is a significant transfer between Rint and Rg from 1980 to 1990, and both are maintained in a relatively stable dynamic equilibrium. After 1990, the vast majority of Rint and Rg transfers to Rs. By 2020, although exports of Rs to the other three runoff components continue to occur, they appear limited compared to the significant increase in Rs itself.

The transfer of runoff components in the central city (Each arc represents each runoff component, and the width of the arc reflects the proportion of each component’s transfer in the total transfer, and the width of the arrows between the arcs represents the transfer amount between runoff components).

Correlation analysis between runoff components and land use types

Tables 2 and 3 show the transfers for the watershed and central city for the five land use types from 1980 to 2020. At both spatial scales, it is the cropland that has the largest amount of transfer out, 684.38 km2 and 481.30 km2 respectively. On the contrary, the expansion of construction land is particularly obvious during this period. The total amount of construction land imported into the watershed is 713.18 km2, of which 491.63 km2 into the central city, accounting for 68.9% of which in the watershed. Water, forest, and grassland have a declining trend, but the transfer is relatively limited because of their own small areas.

Figure 9 shows the evolutionary trend of land use types over the past four decades, with a major transformation from cropland to construction land to meet the development needs brought about by urban expansion and population growth. However, a small amount of construction land has been retransferred to cropland during the past four decades, and this phenomenon is most obvious from 2000 to 2010. The probable reason for this is that the region has taken certain land reclamation measures to curb the further loss of cropland resources, restoring some of the inefficiently utilized construction land to cropland use, thus maintaining the balance of land resources in the region to a certain extent.

The correlation between runoff components and land use types in the study area is shown in Fig. 10. Rs is negatively correlated with cropland, forest and grassland, while Rsat, Rint and Rg are positively correlated with them. All of them have high Pearson correlation coefficients, which are more than 0.93. Rs showed a highly significant positive correlation with construction land. In contrast, the correlations between the four runoff components and water are generally low, with Pearson correlation coefficient basically in the range of ± 0.3. The four runoff components are non-significantly correlated with water, while the correlations with the other four land use types passed the 99% significance level test for significant correlation.

Discussion

In this study, a runoff component discrimination framework covering three kinds of underlying surface features is proposed, and the GRGM model is integrated. Compared with the traditional HI model, the GRGM model has significantly improved the simulation accuracy. The HI model cannot be combined with the complex and variable underlying surface features, and it mainly considers the Rs, which oversimplifies the runoff process. Although the study area has gradually evolved to be dominated by Rs, the other three runoff components also account for a certain proportion. The GRGM model considers the interactions between different runoff components, and though its computational requirement is higher than that of HI model, it can better reflect the actual hydrological situation of the watershed - urban complex system. The improvement of its simulation accuracy is of great significance for the rational planning of water resources and land use layout.

As shown in Fig. 11, the area of water is steadily maintained at a low level, which is much lower than the area of construction land and has no significant trend during the four-decade period. Therefore, although both construction land and water are considered to directly generate Rs in this study, Rs is mainly influenced by construction land, with which it shows a strong correlation. The channel regulation and storage effects enable water to temporarily retain a portion of rainfall instead of immediately generating runoff, thereby buffering Rs. Additionally, water is usually located in low-lying areas with high soil moisture content on its neighboring grids. This can further obscure which runoff component is generated on water. Therefore, although water is thought to be most likely to produce Rs, they are less relevant to Rs due to multiple factors.

The generation of Rs in the study area is closely associated with the expansion of urban areas. Urbanization is usually accompanied by significant growth in construction land, which directly contributes to the increase in impervious surfaces, and consequently a reduction in the generation of groundwater36,37. In contrast, in watersheds that have not been significantly affected by urbanization, the main runoff components are Rsat, Rint and Rg, and the land use types of these watersheds are dominated by forest, grassland and cropland with less construction land16,38. As shown in Fig. 6, runoff components in areas outside the central city in this study area is dominated by Rint and Rg, which coincides with the previous findings and further validates the influence of underlying surface changes on runoff components and their distribution. However, while this study emphasizes the role of natural underlying surface on runoff, in recent years, the construction of green infrastructure has led to complex dynamics in the hydrological system of urbanized watersheds. This study is limited by considering all construction land as impervious surfaces and directly generating Rs, ignoring the inhibitory effect of such facilities on runoff, and considering only underlying surface features. In the future, the effects of climatic factors and complex urban morphology will be further considered to improve the framework of runoff component discrimination, which will facilitate the integration of more refined hydrological models, and provide more scientific and effective theoretical support and practical guidance for runoff forecasting in watershed-urban complex system.

Conclusions

In this study, the spatial distribution characteristics of vertical conductance of soil type, land use type and topographic slope are considered comprehensively, and based on the proposed framework for discriminating easily occurring runoff component, the grid-based runoff generation model GRGM is constructed. The spatial and temporal distribution characteristics of the runoff components and the correlation with land use are analyzed based on the model test. This study analyzes the intrinsic relationship between runoff components and underlying surface changes in the watershed containing highly urbanized areas, with the aim of providing prospective guidance for the management of watershed-urban complex systems. The main conclusions are as follows:

-

(a)

Compared with HI model, the average relative error of runoff generation calculation by GRGM model in the study area is reduced by 27.76%, the average coefficient of determination is increased by 0.11, which means the runoff generation calculation by GRGM model are more accurate.

-

(b)

The Rs in the study area shows a trend of expansion from the central city to the periphery of the watershed, mainly transferred by Rint and Rg. The proportion of Rsat is maintained at a low level for a long time, and it is mainly distributed in the southwest of the study area. Rint and Rg have similar trends and are mainly distributed in areas of the watershed that are not in the central city. The spatial and temporal characteristics of the runoff components reflect the unevenness of the underlying surface change.

-

(c)

From 1980 to 2020, the evolution of land use in the study area is dominated by the dynamic changes between cropland and construction land. Construction land increased significantly and is mainly concentrated in the central city. In addition, there are significant correlations between runoff components and land use types (except water). Among them, Rs is positively correlated with construction land, Rsat, Rint and Rg are negatively correlated with construction land, and all the Pearson correlation coefficients exceed 0.93.

Data availability

The datasets used and analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Shuster, W. D., Bonta, J., Thurston, H., Warnemuende, E. & Smith, D. R. Impacts of impervious surface on watershed hydrology: A review. Urban Water J. 2, 263–275 (2005).

Zhang, N. et al. Understanding the effects of composition and configuration of land covers on surface runoff in a highly urbanized area. Ecol. Eng. 125, 11–25 (2018).

Muhammad, A. H. et al. An integrated land change modeler and distributed hydrological model approach for quantifying future urban runoff dynamics. Sci. China Earth Sci. 67, 3288–3301 (2024).

Schueler, T. R., Fraley-McNeal, L. & Cappiella, K. Is impervious cover still important?? Review of recent research. J. Hydrol. Eng. 14, 309–315 (2009).

de Silva, C., Silva, G. B. L. & M. & da. Cumulative effect of the Disconnection of impervious areas within residential lots on runoff generation and Temporal patterns in a small urban area. J. Environ. Manage. 253, 109719 (2020).

Zambrano, L., Pacheco-Muñoz, R. & Fernández, T. A Spatial model for evaluating the vulnerability of water management in Mexico City, Sao Paulo and Buenos Aires considering climate change. Anthropocene 17, 1–12 (2017).

Guo, Y., Fang, G., Xu, Y. P., Tian, X. & Xie, J. Identifying how future climate and land use/cover changes impact streamflow in Xinanjiang basin, East China. Sci. Total Environ. 710, 136275 (2020).

Liu, C. et al. Study on flood forecasting model of watershed-urban complex system considering the Spatial distribution of runoff generation pattern. Skxjz 34, 530–540 (2023).

Moniruzzaman, M. et al. Decadal urban land use/land cover changes and its impact on surface runoff potential for the Dhaka City and surroundings using remote sensing. Remote Sens. 13, 83 (2021).

Saha, A. & McMaine, J. Applicability and sensitivity of field hydrology modeling by the soil plant air water (SPAW) model under changes in soil properties. Trans. Am. Soc. Agric. Eng. 66, 809–823 (2023).

Mayou, L. A., Alamdari, N., Ahmadisharaf, E. & Kamali, M. Impacts of future climate and land use/land cover change on urban runoff using fine-scale hydrologic modeling. J. Environ. Manage. 362, 121284 (2024).

Fekete, B. M., Vörösmarty, C. J. & Grabs, W. High-resolution fields of global runoff combining observed river discharge and simulated water balances. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles. 16, 15–10 (2002).

Koch, J., Siemann, A., Stisen, S. & Sheffield, J. Spatial validation of large-scale land surface models against monthly land surface temperature patterns using innovative performance metrics. J. Geophys. Research: Atmos. 121, 5430–5452 (2016).

Gaur, S., Singh, B., Bandyopadhyay, A., Stisen, S. & Singh, R. Spatial pattern-based performance evaluation and uncertainty analysis of a distributed hydrological model. Hydrol. Process. 36, e14586 (2022).

Yi, B. et al. Hydrological modelling with an improved flexible hybrid runoff generation strategy. J. Hydrol. 620, 129457 (2023).

Xu, Y. et al. Construction of a semi-distributed hydrological model considering the combination of saturation-excess and infiltration-excess runoff space under complex substratum. J. Hydrology: Reg. Stud. 51, 101642 (2024).

Hu, C., Zhang, L., Wu, Q., Soomro, S. & Jian, S. Response of LUCC on runoff generation process in middle yellow river basin: the Gushanchuan basin. Water 12, 1237 (2020).

Mohajerani, H., Jackel, M., Salm, Z., Schütz, T. & Casper, M. C. Spatial evaluation of a hydrological model on dominant runoff generation processes using soil hydrologic maps. Hydrology 10, 55 (2023).

Schmocker-Fackel, P., Naef, F. & Scherrer, S. Identifying runoff processes on the plot and catchment scale. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 11, 891–906 (2007).

Hümann, M. & Müller, C. Improving the GIS-DRP approach by means of delineatingrunoff characteristics with new discharge relevant parameters. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Information. 2, 27–49 (2013).

Zhang, L. et al. Identifying dominant component of runoff yield processes: a case study in a sub-basin of the middle yellow river. Hydrol. Res. 52, 1033–1047 (2021).

Kumar, H. et al. Site-specific irrigation scheduling using one-layer soil hydraulic properties and inverse modeling. Agric. Water Manage. 273, 107877 (2022).

Bing, J. U., Kening, W. U. & Ganlin, Z. H. A. N. G. I. Ling. Characterization of some calcareous soils from Henan and their proposed classi cation in Chinese soil taxonomy. Pedosphere 27, 758–768 (2017).

Miller, J. D. & Hess, T. Urbanisation impacts on storm runoff along a rural-urban gradient. J. Hydrol. 552, 474–489 (2017).

Akbarimehr, M. & Naghdi, R. Assessing the relationship of slope and runoff volume on skid trails (Case study: Nav 3 district). J. For. Sci. 58, 357–362 (2012).

Garg, V., Nikam, B. R., Thakur, P. K. & Aggarwal, S. P. Assessment of the effect of slope on runoff potential of a watershed using NRCS-CN method. Int. J. Hydrology Sci. Technol. 3, 141–159 (2013).

Standard for Hydrological Information and Forecasting. Henan Provincial Hydrology and Water Resources Survey Center. (2014). http://www.hnssw.com.cn/columnofdepartment51/4673.jhtml

Horton, R. The rôle of infiltration in the hydrologic cycle. Eos Trans. AGU. 14, 446–460 (1933).

Takada, T., Miyamoto, A. & Hasegawa, S. F. Derivation of a yearly transition probability matrix for land-use dynamics and its applications. Landsc. Ecol. 25, 561–572 (2010).

Bashir, O. et al. Simulating Spatiotemporal changes in land use and land cover of the North-Western Himalayan region using Markov chain analysis. Land 11, 2276 (2022).

He, J., Ran, D., Tan, D. & Liao, X. Spatiotemporal evolution of cropland in Northeast China’s black soil region over the past 40 years at the County scale. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 7, 1332595 (2024).

Chen, S., Wang, X., Qiang, Y. & Lin, Q. Spatial–temporal evolution and land use transition of rural settlements in mountainous counties. Environ. Sci. Eur. 36, 1–18 (2024).

Umair, M., Kim, D. & Choi, M. Impacts of land use/land cover on runoff and energy budgets in an East Asia ecosystem from remotely sensed data in a community land model. Sci. Total Environ. 684, 641–656 (2019).

Xu, D., Liu, D., Yan, Z., Ren, S. & Xu, Q. Spatiotemporal variation characteristics of precipitation in the Huaihe river basin, China, as a result of climate change. Water 15, 181 (2023).

Wang, J., Hu, C., Ma, B. & Mu, X. Rapid urbanization impact on the hydrological processes in Zhengzhou, China. Water 12, 1870 (2020).

Kauffman, G. J., Belden, A. C., Vonck, K. J. & Homsey, A. R. Link between impervious cover and base flow in the white clay creek wild and scenic watershed in Delaware. J. Hydrol. Eng. 14, 324–334 (2009).

Oudin, L., Salavati, B., Furusho-Percot, C., Ribstein, P. & Saadi, M. Hydrological impacts of urbanization at the catchment scale. J. Hydrol. 559, 774–786 (2018).

Antonetti, M., Buss, R., Scherrer, S., Margreth, M. & Zappa, M. Mapping dominant runoff processes: an evaluation of different approaches using similarity measures and synthetic runoff simulations. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 20, 2929–2945 (2016).

Funding

This work was funded by National Key Research Priorities Program of China, grant number 2023YFC3209303. National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number U2243219, 51979250.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Yunqiu Jiang: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Reviewing and Editing. Lichun Wang: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Funding, Reviewing and Editing. Tianning Xie: Methodology, Software. Runxi Li: Methodology, Reviewing and Editing. Kejia Wen: Methodology, Software, Editing. Chengshuai Liu: Software, Reviewing and Editing. Caihong Hu: Reviewing and Editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jiang, Y., Wang, L., Xie, T. et al. Study on the effect of underlying surface changes on runoff generation in the urbanized watershed. Sci Rep 15, 15056 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-95295-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-95295-1