Abstract

This paper proposes a novel MZI (Mach–Zehnder Interferometer) structure for high-speed optical encryption in Optical Transmission Networks (OTNs) operating at 100 Gbps with OTU4 signaling on a silicon-based optical fiber substrate. The design achieves a significantly lower \({V}_{\pi }l\) (half-wave voltage length) compared to existing MZIs by engineering the material profile of the MZI arm cladding. Additionally, it introduces a novel approach by utilizing the dispersive arm for precise control of reflecting power. This optimized MZI exhibits a \({V}_{\pi }l\) of approximately 13.5 V mm and a bandwidth of 116.5 GHz, resulting in a figure of merit (FOM) of 8.630 GHz/V mm. This represents an 86% improvement over comparable MZI designs, highlighting the significant performance enhancement. Furthermore, the proposed MZI boasts the smallest footprint among similar implementations. Notably, the entire structure, including the synchronizer and switch, leverages the MZI principle. This MZI-based design holds promise for efficient and compact optical encryption in 100 Gbps OTNs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The huge amount of sensitive data that is transmitted over fiber optic infrastructure networks doubles the need for protection and encryption1,2,3. Contrary to the common misconception that optical fibers are inherently secure due to a lack of publicized hacking incidents, eavesdropping and unauthorized access are real threats4,5. Because in-flight data is vulnerable to interception, encryption is a critical security measure in this domain. Several advantages, including lower costs, reduced complexity, decreased latency, ease of implementation, flexibility, and scalability, underscore the superiority of encryption in optical data transmission compared to other security methods. Consequently, encryption plays a vital role in ensuring the security and integrity of information in modern communication. Adopting this approach not only addresses the challenges of secure data exchange but also lays the foundation for a safe and reliable network for future generations. Various solutions for information encryption typically involve converting optical signals to electrical signals for encryption, followed by reconversion to optical form (OEO conversion). However, high-speed electrical encryption is often challenging and expensive due to the limitations of electronic components6. This highlights the necessity for systems capable of performing encryption at high speeds with low latency. To address the growing demand for high-speed optical data encryption, recent advancements have explored the integration of PIN-diode-based Mach–Zehnder Modulators (MZMs) using silicon-on-insulator (SOI) technology. This approach enables reduced power consumption, smaller device footprints, and improved modulation efficiency, making it ideal for secure optical transmission7,8. Additionally, the use of traveling wave modulators (TWMs) with optimized shallow ridge InP structures has demonstrated 81 GHz 3-dB bandwidth, supporting beyond 200 Gbps data rates, critical for modern telecommunication networks9.

In-flight data encryption at the optical layer has significant advantages over traditional encryption solutions that operate at higher network layers. Optical encryption provides maximum throughput without impacting performance and transparent transmission of any protocol without additional hardware. This becomes a low-latency encryption solution that is more bandwidth efficient. Since 2002, efforts have been made to develop all-optical encryption methods that eliminate the need for optical-to-electrical conversions. For instance, Jing et al. proposed a high-speed optical communication scheme using simultaneous chaotic spectral phase encoding and decoding10. Jao et al. introduced an optical encryption scheme for fiber optic communication systems that employs wavelength division coherency through private chaotic phase mixing11. Cui et al. examined chaotic encryption methods in wavelength division multiplexing (WDM)12, while Djordjevic et al. explored the application of fiber Bragg gratings (FBGs) in all-optical encryption, analyzing corresponding encoders and decoders, optical code-division multiple access (OCDMA), and optical cryptography13. Despite their promise, these methods often introduce noise into the system due to high power levels and signal distortion, making the hidden information potentially recoverable using advanced techniques.

Quantum key distribution (QKD) represents a new frontier in all-optical encrypted communication. This secure method utilizes a cryptographic protocol based on quantum mechanics, allowing two parties to share a secret random key for encrypting and decrypting messages. Diamanti et al. have explored the application of QKD in optical network encryption14. A unique aspect of QKD is that it enables communicating users to detect any third-party attempts to access the key. Experimental QKD has demonstrated secure key distribution over distances of approximately 100 km using standard telecom fibers and in free space, achieving secure key rates of several Mbps. However, due to the lower speed of data transfer in this method, QKD is primarily employed for key distribution, rather than for transmitting messages. The generated key can then be utilized with any encryption algorithm to secure the actual message, which is sent through standard telecommunications channels15.

Given the points discussed, the demand for safe and high-speed encryption methods is increasingly critical. Cryptographic techniques that utilize XOR operations between input data and a cipher string are among the most effective methods for encrypting digital data, with their security remaining uncompromised16. Researchers such as Parandin et al., Yang et al., and Salmanpour et al. have explored the use of logic gates in all-optical cryptography17,18,19. In all-optical encryption that employs optical logic gates, on–off keying (OOK) modulation is typically used. However, in practical applications, OOK modulation faces limitations at rates exceeding 10 Gbps due to issues such as dispersion.

Communication between modern data centers relies heavily on OTNs, enabling transfer rates that exceed 100Gbps using coherent modulation techniques20,21,22. In coherent modulation, information is encoded in the phase of the signal23,24. By scrambling the data phase at the transmitter and recovering it at the receiver, a form of encryption can be achieved. This process necessitates phase modulators with suitable bandwidth, with Mach–Zehnder modulators (MZM) being commonly employed. A key design goal for these modulators is their integration on silicon substrates while maintaining compact footprint. Important parameters include bandwidth, half-wave voltage (\({V}_{\pi }\)), and device footprint. A common FOM is the product of the half-wave voltage and the length of the device (\({V}_{\pi }l\)), emphasizing the need for high efficiency and scalability. To address the demand for efficient and scalable electro-optical modulators in modern telecommunications, significant efforts have focused on various materials, leading to the development of compact devices with wide bandwidth. Electro-optical modulators can be constructed from materials such as Silicon (Si)7,8,25, Indium Phosphide (InP)9,26, Aluminum Nitride (AlN)27, plasmonic28, graphene29, polymers30, and Lithium Niobate (LN). Each material has its drawbacks: InP is temperature unstable, AlN has low switching efficiency, plasmonic suffers from high intrinsic loss, graphene lacks scalability, and polymers exhibit long-term instability31. In contrast, LN offers good temperature stability, a large transparent optical window (350 ~ 5000 nm), low absorption, and a highly effective nonlinear Pockels effect (30 pm/V). Traditional LN modulators utilize a bulk configuration. Due to the crystalline structure of the core material, the refractive index difference between the core and cladding must be minimal (\(\Delta n<0.02\)), which leads to larger footprint to mitigate bending losses. However, these dimensions are often too large for integration, making them less scalable31,32,33. Thin film lithium niobate (TFLN) on insulator represents an emerging solution to these challenges. Unlike bulk LN, TFLN enables higher intensity per unit power in waveguides, resulting in a stronger nonlinear optical effect and shorter interaction lengths. Additionally, photonic waveguides based on TFLN can achieve sub-micron footprint with low propagation loss and a small bending radius. This design allows RF electrodes to be placed in close proximity to the waveguide at the micrometer scale, enhancing the overlap between optical and microwave fields, and ultimately increasing electro-optical modulation efficiency31,32,33,34.

This paper presents, for the first time, a novel structure for encrypting OTNs at the OTU4 rate using DP-QPSK coherent modulation. The proposed architecture employs an MZM fabricated on a TFLN on silicon substrate, integrated with a custom-designed switch. The paper first examines the fundamental principles of Mach–Zehnder phase modulation and QPSK modulation. It then details the proposed encryption structure and analyzes the results obtained from the dissipative edge design. The paper is organized as follows: Sect. 2 discusses Mach–Zehnder phase modulators; Sect. 3, QPSK modulation; Sect. 4, the proposed encryption structure; Sect. 5, the dissipative arm design and analysis; and Sect. 6, the conclusion.

Mach–Zehnder phase modulators

Silicon MZMs are widely favored for their high thermal tolerance and broad bandwidth35,36. In a Mach–Zehnder phase modulator, the phase change of light is controlled by an electrical signal, which can be adjusted in terms of frequency, amplitude, or pulse width. This capability allows for rapid phase modulation of the optical signal, making it ideal for high-speed data transmission. One significant advantage of these modulators is their independence from light polarization, enabling effective operation at high frequencies37. Additionally, they can achieve continuous and precise phase adjustments, accommodating light waves of various wavelengths. This versatility allows for the modulation of optical signals across different wavelengths. Structurally, MZMs are relatively simple, with components that can be easily manufactured and integrated. This makes them an economical choice for various optical systems. Furthermore, their scalability is a key benefit, allowing multiple modulators to be connected within an optical network for multi-channel modulation and analysis. Another important feature of MZMs is their low noise level, which minimizes the impact of noise on the quality of the modulated signal. With these modulators, the phase of light can be accurately controlled, enabling continuous adjustments in response to changing settings and system requirements.

Considering the structure of Fig. 1, we will have:

By simplifying the formula, we will have:

By observing the formula, the effect of applied voltage on the structure and modulation of information can be seen.

QPSK modulation

Although intensity modulation with direct detection (IM/DD) methods offers system simplicity and relatively low cost, their sensitivity is limited by noise generated in the light detector and receiver preamplifier. This noise adversely affects the receiver sensitivity of IM/DD transmission systems. However, improvements in the components, spectral purity, and frequency stability of semiconductor lasers have made alternative techniques, such as homodyne or heterodyne detection of optical signals, viable. Optical communication systems utilizing homodyne or heterodyne detection are known as coherent optical communication systems, as their performance relies on the phase coherence of the optical carrier. In these coherent detection techniques, light functions as a carrier medium, similar to methods used in amplitude, frequency, or phase-modulated microwave radio systems. As data transfer rates have increased to 10 Gbps and beyond, the adoption of coherent modulation techniques has also risen. This trend is driven by the fact that coherent detection allows for higher spectral efficiency and greater tolerance to chromatic and polarization state dispersion compared to direct detection methods38.

Until around 2002, most optical communication systems operated at data rates of up to 2.5 Gbps per wavelength using on–off keying (OOK) signals in non-return-to-zero (NRZ) or return-to-zero (RZ) formats. As the demand for higher data transfer speeds grew, the concept of using multi-level modulation formats gained significant attention. Quadrature phase shift keying (QPSK), a multi-level modulation method, enables the transmission of more than one bit per symbol by encoding information with four distinct phase shifts. Each of these phase shifts can represent a specific pair of bits. Consequently, for a given data rate, the symbol rate in QPSK is halved, reducing spectral occupancy and easing the requirements for both transmitters and receivers compared to modulation schemes like OOK38.

In this case, the output waveform according to Figs. 2 and 3 will be as follows:

The proposed structure

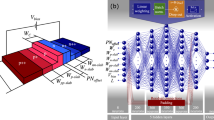

To implement the proposed structure for encrypting the optical fiber infrastructure network, devices must be strategically placed along the transmission path, as illustrated in Fig. 4. In this setup, encoders are essential for transforming the information received from the transmitter according to a specified sequence. Given that this information is encoded in phase, precise handling of the phase is crucial.

Once the information traverses the optical fiber and reaches the receiver, it needs to be recovered in its original form, necessitating the use of a decryptor. For encrypting information using QPSK modulation, the phase of the entire data set must be adjusted in accordance with a specific order. If the electric field of electromagnetic plane waves incident on the device is as \(\overrightarrow{E}\left(\overrightarrow{r,}t\right)\)39 where

the electric field of these waves after passing through the phase modulator will be as follows:

When the light passes through the communication channel and after passing through the modulator, we will have the second phase:

In order to be able to recover the information in the receiver correctly, you must:

Let it be true that \(n\in \text{\rm N}\).

To implement encryption operations in coherent modulations, it is essential to design phase modulator devices that ensure the received wave is in phase with the initial wave after the encryption process. The steps involved in this process are illustrated in Fig. 5.

Encrypting steps by displaying information at the system level (a) Clear information received from the OTN switch (b) Encrypted information on the transmitter side (c) Encrypted information received after passing through the channel on the receiver side (d) Decrypted information on the receiver side.

To meet the specifications of the encryption device, an 80 km long optical fiber link was simulated. For achieving a data rate of 100Gbps using DP-QPSK modulation, as illustrated in Fig. 6 each polarization must support a data rate of 50Gbps. The wavelength of the incident light in this link is set at 1550 nm. The design of the link follows the specifications outlined in Fig. 4.

Simulation results indicate that the bandwidth required for the phase modulator is 50 GHz. Therefore, the modulator must be designed to meet or exceed this bandwidth requirement.

In this paper, in addition to providing a structure to create encryption in the link, we introduce the components of this tool. The proposed structure is presented in this paper for the first time. In this structure, two components of modulator and switch are used, and each of these two components has a special structure in its own way. In order to implement the encryption path, it is necessary for the encoder and decoder to synchronize with each other in order to start the encryption operation. Therefore, at first, according to Figs. 7 and 8, it is necessary to implement a switch in the sending and receiving path. These structures consist of three parts: the synchronizer part, the phase modulator part and the switch part. In the synchronizer section, the encryptor and decryptor will be synchronized by sending a special pattern to the sender. In the phase modulator section, it changes the phase of the OTN transmitter information with the information coming from the encryption section. In the switch section, with the decision information coming from the receiver, it changes the path to the synchronizer or modulator. In the synchronizer section, decisions are made based on the information received from the sender. At the receiver part, in the phase modulator section, the received information will be decoded. MZM design is also required for the encoding and decoding path. Therefore, according to these cases, it is necessary to design a MZI with our desired parameters.

In the optimal design of the modulator, important parameters include insertion losses, which should be minimized, the design of the device with small footprint, the switch voltage (\({V}_{\pi }\)) to reduce driving voltage and lower costs associated with driver amplifiers, resulting in decreased power consumption and thermal losses. This leads to enhanced electro-optical bandwidth, which requires the design of devices with small capacitors to achieve the appropriate bandwidth.

To compare different designs and create an optimal one, the FOM is defined as the product of the device length and the half-wave voltage (\({V}_{\pi }l\)). In this regard, the MZM is a suitable option. The Push–Pull modulator design increases RF power by 3 dB and significantly reduces noise levels due to the elimination of common mode noise11. Therefore, with \({V}_{\pi }\) at half of the single drive, optimal efficiency can be achieved.

To reduce return loss in the Y-branch and prevent device overheating40, directional couplers are used in the input and output of the MZM. In our design as shown in Fig. 9, the arm length of the directional coupler is 71 µm, the thickness of the LN core is 900 nm, the distance between the two waveguide cores is 200 nm, the bending radius is 600 µm, the length of the MZM arm is 1 mm, and the device height is 300 nm.

To improve the performance of the modulator and eliminate common mode noise, a Push–Pull combination has been used. Additionally, to reduce the FOM, \({V}_{\pi }l\), it is necessary to increase the electric field inside the device. For this purpose, we will incorporate a material with higher transmittance than the sheath material in the clad layer of the modulator. By changing the value of the permeability coefficient of the clad, we will have:

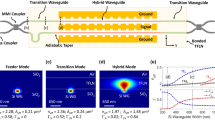

By changing \(ff\) ( Filling factor.) from 0 to 1 and applying it in COMSOL Multiphysics software, the diagram in Fig. 10 is obtained. As can be seen in Fig. 10, by changing the filling factor and the transmittance coefficient as well as the change in the field inside the clad, it is possible to achieve suitable values of \({V}_{\pi }l\). Considering \(ff=0\), the entire material of the clad is composed of extension material; As shown in Fig. 10, \({V}_{\pi }l\approx 10\,V mm\) is obtained. By assigning \(ff=1\), the value of \({V}_{\pi }\) will be about 17.5 V mm. With a change in the cladding material, the refractive index will also change, resulting in an alteration of the electromagnetic field’s penetration within the cladding. This variation is attributed to the changing refractive index difference between the core and the cladding. Consequently, the losses will be affected, as illustrated in Fig. 11. Hence, there is a tradeoff for material selection. Therefore, in order to get better results, penetration of the added material with a special profile has been done. Figure 12 shows the light confinement inside the waveguide. As seen in Fig. 13, the value of \({V}_{\pi }l\approx 13.5\,V mm\) is reported. With the simulation performed on this structure, the bandwidth of the device is calculated to be around 116.5 GHz.

Figure 14 clearly show the switching performance of the designed device.

By examining the obtained results and related papers whose values of \({V}_{\pi }l\) and their bandwidth are listed in Fig. 15, it is clear that the lowest value of \({V}_{\pi }l\) in previous papers, as shown in Table 1, is equal to 14.1 V mm and the highest value of the bandwidth was 110 GHz; In both cases, the values obtained in this paper are optimal. As an FOM that we have defined, \(B.W./{V}_{\pi }l\) gives a very good view for comparing papers. Accordingly, the FOM for the mentioned papers is shown in Fig. 16. As seen in this figure, in the present work, this FOM is equal to 8.630 GHz/V mm, which is optimal compared to other papers.

Comparison chart of \({\text{V}}_{\uppi }\text{l}\), bandwidth and arm length of the modulators of the papers in Table 1 with our designed modulator.

Defined FOM in our work compared to papers in Table 1.

The dissipative arm design

Leaving an edge in the path selection process causes reflection in the switch, which, in addition to causing loss in the path, will also cause interference and damage to the device’s performance. In order to solve this problem, there is a need to design a device that works in such a way that it creates a loss in itself and prevents reflection to the main device.

From the point of view of wave optics and the principle of impedance matching, in two structures that are adjacent to each other, the wave propagates between the two structures when the maximum impedance matching is achieved. The equivalent impedance of each layer is calculated based on the molecular characteristics of the material and more simply, from its refractive index. As the difference in refractive index of two materials is minimized, the impedance matching is also maximized, which means that if the impedance is fully matched, the wave will propagate without reflection from the common boundary of the two layers. On the contrary, the lower the impedance matching, the more the reflection will be and it will lead to malfunction of the device48,49,50,51,52.

In this paper, inspired by the above principle, the desired structure is considered as hierarchical layers, where each layer is in the maximum state of impedance matching or the lowest difference in refractive index compared to its adjacent layer. Therefore, we will face a structure where from the beginning of the waveguide to its end, the refractive index of the core decreases smoothly to the refractive index of the clad, whose refractive index profile is as shown in Fig. 17.

In this design, the length of the dissipative edge is considered equal to the length of the MZM arm. By simulating this edge, Fig. 18 is obtained. The results of the simulation show that the reflected field power at the input port of this edge is equal to 7.74 × 10-15w/m, which indicates that no light is reflected and all of it is lost in the edge. This problem indicates that the layer is a perfect absorber. Figure 19 also shows the function of this edge in combination with the main device.

Conclusion

As far as the authors of this paper know, not many people have worked in the field of optical encryption of OTNs. In this paper, a new structure for encryption of OTN at 100Gbps rate with OTU4 signaling on optical fiber substrate using MZI on silicon substrate was presented. This structure was introduced for both encryption and decryption sections. Both encryption and decryption sections were composed of three sections: phase modulator, synchronizer and switch. In this structure in the MZI section, the bandwidth reached 116.5 GHz and the FOM, \({V}_{\pi }l\), reached about 13.5 V mm. To make an effective comparison between the designed structure and other structures introduced in recent papers, the FOM, \(B.W./{V}_{\pi }l\) was introduced. The value obtained from this FOM in this paper was 8.630 GHz/V mm, which is considered as a new record in this field. To prevent the loss and heating of the device in the unused outputs, a dissipative waveguide was introduced as a complete absorber layer.

According to the obtained results, the structure designed in this paper is suitable for the encryption of OTNs with OTU4 signaling and at a rate of 100Gbps.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Lin, J., Bo, F., Cheng, Y. & Xu, J. Advances in on-chip photonic devices based on lithium niobate on insulator. Photonics Res. 8(12), 1910–1936 (2020).

Mian, Z., Wang, C., Kharel, C., Zhu, D. & Lončar, M. Integrated lithium niobate electro-optic modulators: When performance meets scalability. Optica 8(5), 652–667 (2021).

Ritter, M., Illmer, C. Optical network encryption—a new key to data security. ADVA Opt. Netw. (2012).

https://www.ciena.com/insights/what-is/What-Is-Optical-Encryption.html.

Gao, Z. et al. 32 Gb/s physical-layer secure optical communication over 200 km based on temporal dispersion and self-feedback phase encryption. Opt. Lett. 47(4), 913–916 (2022).

Agarwal, V. & Chaurasia, V. A review on all optical encryption and decryption methods. IJTRD 2(4), 80–84 (2015).

Moshaev, V., Leibin, Y. & Malka, D. Optimizations of Si PIN diode phase-shifter for controlling MZM quadrature bias point using SOI rib waveguide technology. Opt. Laser Technol. 138(4), 106844 (2021).

Sitbon, E., Ostrovsky, R. & Malka, D. Optimizations of thermo-optic phase shifter heaters using doped silicon heaters in Rib waveguide structure. Photonics Nanostruct. Fundam. Appl. 51, 101052 (2022).

Yao, R. et al. Design optimization of a shallow ridge InP traveling-wave MZI modulator for 200 Gb/s data transmission," in CLEO: Fundamental Science 2023 (CA United States, 2023).

Jiang, N., Zhao, A., Xue, C., Tang, J. & Qiu, K. Physical secure optical communication based on private chaotic spectral phase encryption/decryption. Opt. Lett. 44(7), 1536–1539 (2019).

Zhang, M., Wang, C., Kharel, P., Zhu, D. & Lončar, M. Integrated lithium niobate electro-optic modulators: When performance meets scalability. Optica 8(5), 652–667 (2021).

Cui, M. et al. Chaotic RNA and DNA for security OFDM-WDM-PON and dynamic key agreement. Opt. Express 29(16), 25552–25569 (2021).

Djordjevic, I. B., Saleh, A. H. & Küppers, F. Design of DPSS based fiber bragg gratings and their application in all-optical encryption, OCDMA, optical steganography, and orthogonal-division multiplexing. Opt. Express 22(9), 10882–10897 (2014).

Diamanti, E., Lo, H.-K., Qi, B., Yuan, Z. Practical challenges in quantum key distribution. NPJ Quant. Inf. 2 (2016).

Golovko, G., Matiashenko, A., Solopihin, N. Data encryption using xor cipher Iнфopмaцiйнi тexнoлoгiї, 81–83 (2021).

Parandin, F., Karkhanehchi, M.M. Terahertz all-optical NOR and AND logic gates based on 2D photonic crystals. Superlattices Microstruct. (2016).

Yang, X., Hu, X., Yang, H. & Gong, Q. Ultracompact all-optical logic gates based on nonlinear plasmonic nanocavities. Nanophotonics 6(1), 365–376 (2017).

Salmanpour, A., Mohammadnejad, S., Bahrami, A. All-optical photonic crystal AND, XOR, and OR logic gates using nonlinear Kerr effect and ring resonators. J. Mod. Opt. (2015).

Schubert, A. G.709—the optical transport network (OTN) (VIAVI Solutions Inc., 2021).

Littlewood, P., Masoud, F. & Loro, M. Optical Transport Networking (Ciena Corporation, 2015).

ITU-T G.872, Architecture of optical transport networks. ITU, USA (2019).

Laperle, C., Villeneuve, B., Zhang, Z. & McGhan, D. WDM performance and PMD tolerance of a coherent 40-Gbit/s dual-polarization QPSK transceiver. J. Light. Technol. 26(1), 168–175 (2008).

Kumar, P. Coherent implementation in optical communication. Ciena Corporation (2019).

Dong, P. et al. Low Vpp, ultralow-energy, compact, high-speed silicon electro-optic modulator. Opt. Express 17(25), 22484–22490 (2009).

Li, Y., Wang, R., Bhardwaj, A., Ristic, S. & Bowers, J. High linearity InP-based phase modulators using a shallow quantum-well design. IEEE PTL 22(18), 1340–1342 (2010).

Xiong, C. et al. Aluminum nitride as a new material for chip-scale optomechanics and nonlinear optics. New J. Phys. 14(9), 092014 (2012).

Melikyan, A. et al. High-speed plasmonic phase modulators. Nat. Photonics 8, 229–233 (2014).

Mohsin, M., Neumaier, D., Schall, D., Otto, M., Matheisen, C., Giesecke, A. L., Sagade, A. A., Kruz, H. Experimental verification of electro-refractive phase modulation in graphene. Sci. Rep. 5 (2015).

Lee, M. et al. Broadband modulation of light by using an electro-optic polymer. Science 298, 1401–1403 (2002).

Wang, C., Zhang, M., Stern, B., Lipson, M. & Lončar, M. Nanophotonic lithium niobate electro-optic modulators. Opt. Express 26(2), 1547–1555 (2018).

Wang, C. et al. Integrated lithium niobate electro-optic modulators operating at CMOS-compatible voltages. Nature 562(7725), 101–104 (2018).

Ren, T. et al. An integrated low-voltage broadband lithium niobate phase modulator. IEEE PTL 31(11), 889–892 (2019).

Han, H., Xiang, B. Simulation and analysis of electrooptic tunable microring resonators in silicon thin film on lithium niobate. Sci. Rep. 9 (2019).

Dong, P., Chen, Y.-K., Duan, G.-H. & Neilson, D. T. Silicon photonic devices and integrated circuits. Nanophotonics 3(4–5), 215–228 (2014).

Wang, J. et al. Silicon high-speed binary phase-shift keying modulator with a single-drive push–pull high-speed traveling wave electrode. Photonics Res. 3(3), 58–62 (2015).

Paschotta, R., Electro-optic Modulators, RP Photonics Encyclopedia, 2024. Available: https://www.rp-photonics.com/electro_optic_modulators.html.

Keiser, G., Otical fiber communications, McGraw-Hill Education (2011).

Paschotta, R., Optical Phase, RP Photonics Encyclopedia (2024).. Available: https://doi.org/10.61835/870.

Klein, H., Integrated InP Mach-Zehnder Modulators for 100 Gbit/s Ethernet Applications using QPSK Modulation, Berlin (2010).

Xu, M. et al. High-performance coherent optical modulators based on thin-film lithium niobate platform. Nat. Commun. 11, 3911 (2020).

Liu, X. et al. Wideband thin-film lithium niobate modulator with low halfwave-voltage length product. COL 19, 060016 (2021).

Mercante, A. J. et al. 110 GHz CMOS compatible thin film LiNbO3 modulator on silicon. Opt. Express 24(14), 15590–15595 (2016).

Mercante, A. J. et al. Thin film lithium niobate electro-optic modulator with terahertz operating bandwidth. Opt. Express 26(11), 14810–14816 (2018).

Liu, Y. et al. Low Vπ thin-film lithium niobate modulator fabricated with photolithography. Opt. Express 29(5), 6320–6329 (2021).

Yang, F. et al. Monolithic thin film lithium niobate electro-optic modulator with over 110 GHz bandwidth. COL 20(2), 022502 (2022).

Chen, N., Lou, K., Yu, Y., He, X. & Chu, T. High-efficiency electro-optic modulator on thin-film lithium niobate with high-permittivity cladding. Laser Photonics Rev. 17(11), 2200927 (2023).

Southwell, W. H. Pyramid-array surface-reliefstructures producing antireflection index matching on optical surfaces. J. Opt. Soc. Am. A 8(3), 549–553 (1991).

Bräuer, R. & Bryngdahl, O. Design of antireflection gratings with approximate and rigorous methods. Appl. Opt. 33(34), 7875–7882 (1994).

Raguin, D. H. & Morris, G. M. Antireflection structured surfaces for the infrared spectral region. Appl. Opt. 32(7), 1154–1167 (1993).

Kikuta, H., Ohira, Y., Kubo, H. & Iwata, K. Effective medium theory of two-dimensional subwavelength gratings in the non-quasi-static limit. J. Opt. Soc. Am. A 15(6), 1577–1585 (1998).

Dobrowolski, J. A., Poitras, D., Ma, P., Vakil, H. & Acree, M. Toward perfect antireflection coatings: Numerical investigation. Appl. Opt. 41(16), 3075–3083 (2002).

Acknowledgements

This research is based on the first author’s PhD thesis in 2024. The first author also acknowledges and greatly appreciates the scientific support of Dr. Kambiz Abedi from Shahid Beheshti University of Tehran throughout all stages of this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A. K. and K. A. wrote the main manuscript text. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Khalili, A., Abedi, K. Design and analysis of optical encryption for optical transport networks with a rate of 100Gbps based on Mach–Zehnder interferometers. Sci Rep 15, 12328 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-95314-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-95314-1