Abstract

A multimodal emotion recognition method that utilizes facial expressions, body postures, and movement trajectories to detect fear in mice is proposed in this study. By integrating and analyzing these distinct data sources through feature encoders and attention classifiers, we developed a robust emotion classification model. The performance of the model was evaluated by comparing it with single-modal methods, and the results showed significant accuracy improvements. Our findings indicate that the multimodal fusion emotion recognition model enhanced the precision of emotion detection, achieving a fear recognition accuracy of 86.7%. Additionally, the impacts of different monitoring durations and frame sampling rates on the achieved recognition accuracy were investigated in this study. The proposed method provides an efficient and simple solution for conducting real-time, comprehensive emotion monitoring in animal research, with potential applications in neuroscience and psychiatric studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Emotions are intrinsic responses of organisms to external stimuli that directly influence their behaviour, cognition, and physiological states. Research on animal emotions not only helps reveal animal behaviour patterns1 but also provides important insights for neuroscience2, psychiatric research3, and drug screening4. In particular, fear, as a critical physiological response to threats, plays a crucial role in survival adaptation, decision-making, and memory formation processes5,6. The detection and analysis of fear are essential for understanding the emotional mechanisms of animals and their manifestations in behaviour.

Currently, animal emotion research relies primarily on behavioural observations7 and physiological measurements8. Common emotional assessment methods involve inferring an animal’s emotional state by observing behaviours such as movements and monitoring physiological signals. However, these traditional methods are often subjective and inefficient, and they involve complex measurements that fail to comprehensively capture emotional changes in real time. This is especially true when complex emotional responses are monitored, as single-dimensional behavioural and physiological data may not accurately reflect an animal’s emotional state.

In recent years, with the advancement of technologies such as computer vision9, motion tracking10, posture recognition11, and multimodal encoding12, emotion recognition approaches based on multimodal data (e.g., facial expressions, body postures, and movement trajectories) have shown potential13. Facial expressions, posture changes, and movement trajectories are critical indicators of an animal’s emotional state, reflecting its immediate emotional responses. By combining these different features, multimodal learning methods can enable more accurate and comprehensive emotional assessments to be conducted. Multimodal emotion detection methods not only increase the accuracy of emotion recognition but also compensate for the limitations of single-modal data, thereby improving overall performance.

In the field of mouse emotion recognition2,14, several studies have been conducted to evaluate emotional states through facial expression analyses, posture analyses, or trajectory analyses. Changes in facial expressions, such as eye, ear, and mouth movements, have been shown to correlate with the emotional states of mice. Posture analysis techniques15,16, such as PoseNet11, OpenPose17 and DeepLabCut18, have made preliminary progress in the mouse posture and motion recognition field. Additionally, movement trajectory10,19 analyses can reveal spatial exploration behaviours, providing inferences about emotional changes. However, the existing studies still face certain limitations, especially when detecting fear emotions, where a single data source often does not provide sufficient information for accurately assessing the target emotional state. Thus, how to integrate multimodal data to improve the precision and reliability of emotion detection remains an unresolved issue.

In this study, we aim to develop a multimodal emotion recognition method based on facial expression, body posture, and movement trajectory analyses, focusing on the detection of fear in mice via a single camera in a home cage setup. Through the fusion of multimodal data and advanced deep learning and machine learning methods, we hope to accurately capture the behaviours associated with fear in mice, providing a more efficient and objective solution for animal emotion monitoring and simplifying the experimental complexity of the fear emotion recognition process. This research will not only deepen our understanding of the relationships between mouse emotions and behaviours but also provide significant technical support for neuroscience, drug screening, and psychiatric studies.

Related works

Traditional emotion assessment methods

The traditional animal emotion research relied primarily on behavioural observations and physiological signal measurements20. The behavioural observation method infers emotional states by recording animals’ movement patterns21; exploratory behaviours; and specific emotion-related behaviours, such as avoidance, staring, and freezing22. The open field test23, elevated plus maze24, and conditioned fear test25 are widely used to assess anxiety and fear emotions in animals. However, these methods rely on manual scoring, which introduces strong subjectivity and low reproducibility26. The physiological measurement method evaluates the emotional states of animals by recording physiological signals such as heart rates, cortisol levels, and electroencephalography27. For example, an elevated cortisol concentration is commonly considered a physiological marker of stress and anxiety, whereas heart rate variability can be used to assess autonomic nervous system activity. Although these methods provide objective physiological data, their measurement processes often require invasive equipment, which may interfere with the target animals natural behaviour28. Additionally, physiological signals are influenced by multiple factors, making it difficult for a single physiological measure to accurately reflect an animals true emotional state.

Applications of computer vision and deep learning in emotion detection

In recent years, advancements in computer vision and deep learning technologies have provided new directions for animal emotion detection research29. Facial expression analysis, posture recognition, and movement trajectory analysis have emerged as key research focuses in this field30,31. The existing methods focus primarily on single-modal data analyses, inferring animal emotional states on the basis of vocalizations32. However, single-modal approaches have limitations in terms of their accuracy and robustness. The emotional expressions of animals are typically multimodal, and relying on a single modality may fail to comprehensively capture the full spectrum of emotional characteristics33,34. However, the current multimodal emotion recognition methods still face challenges, particularly regarding the collection and synchronization of different modalities, which present significant technical difficulties. Additionally, data fusion strategies for use across multiple modalities remain underdeveloped, and how to effectively integrate multisource information to achieve enhanced model performance remains an open research question35.

Methods

Animal experimental design

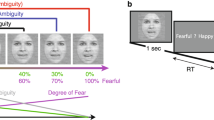

In this study, healthy adult BALB/c mice (both from the Beijing Vital River Laboratory Animal Technology Co., Ltd., 8-12 weeks old) were used, with 20 mice per experimental group, for a total of 100 mice. All the mice were allowed to acclimate for 1-2 days before the experiment to minimize the stress caused by environmental changes. In the experimental group, the mice were exposed to mild electric shocks (2 second, 1.5 mA) in a fear-inducing context36, whereas the control group was allowed to move freely in a neutral environment without any threats.

Each mouse was subjected to three different experimental conditions to comprehensively assess its fear responses, with each trial lasting 10 minutes. The experimental conditions included a fear-inducing experiment, where the mice were exposed to mild electric shocks to trigger fear responses, and a control experiment, where the mice were free to explore in a neutral environment to record their baseline behaviour. Each mouse was subjected to three repetitions of each experiment to ensure the reliability and consistency of the acquired data. Randomization was used to minimize experimenter bias, and a 24-hour rest period was implemented between trials to allow for emotional recovery. All the mice were euthanized after the experiment via an overdose of sodium pentobarbital (100 mg/kg).

To more comprehensively assess fear responses, the freezing behaviour was incorporated as a measure of the fear levels of the mice37,38,39. Freezing, defined as the cessation of all movement except for respiration, was recorded via video tracking software to capture the total duration and frequency of freezing. During each 10-minute trial, the freezing behaviour was assessed in both the fear-inducing and neutral conditions. The percentage of time spent freezing was calculated for each mouse by dividing the freezing time by the total trial time. This evaluation allowed for a more objective and quantifiable measure of the emotional responses to fear-inducing and control conditions. The freezing time data were averaged across three experiments for each mouse and statistically analysed to compare the freezing behaviours observed under different conditions. The emotional impact of the fear stimuli was assessed by comparing the freezing behaviour differences between the experimental and control groups.

Data collection and preprocessing

High-definition cameras (with 100-Hz frame rates) were used to record mouse behaviours and capture facial expressions, body posture changes, and movement trajectories. The cameras were placed at the side of the experimental environment to capture a comprehensive view of the behaviours of the mice. Each trial lasted 10 minutes, and both the experimental and control groups were recorded under different conditions.

Given the single-side camera setup, it was necessary to precisely calibrate the positions of the mice in the video data. We used the ResNet50-based40 DeepLabCut18 deep learning model, which was fine-tuned with minimal annotated data, to track the movement trajectories and key position points of the mice on the floor of the arena. The position calibration algorithm transformed the 2D video data into real-world mouse location distributions, significantly improving the accuracy of the movement trajectories.

For posture extraction purposes, the pretrained DeepLabCut18 network based videos’ key frames was used to automatically detect key body points and generate a continuous posture feature sequence. Regarding facial feature extraction, the Fast region-based convolutional neural network (R-CNN)41 model was employed to detect and precisely locate the faces of the mice, extracting facial regions for determining emotion-related features. To handle potential missing facial data caused by rapid movements or view angle limitations, we introduced a blank token to maintain the consistency of the multimodal data, reduce biases during the feature fusion process and improve the robustness of the emotion recognition model.

Construction of the multimodal emotion classification model

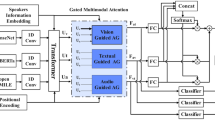

To effectively integrate the acquired facial images, posture sequences, and position coordinates into a unified input for emotion classification, the data were encoded accordingly. Given that emotion recognition relies not only on static features but also on temporal context, particularly for posture and position features, we used a temporal-aware encoder to process the obtained frames over time, capturing temporal dependencies. The resulting encoded matrix was then input into a bidirectional encoder representations from transformers (BERT)-based model for emotion classification. The overall model architecture is shown in Fig. 1.

Temporal-aware multimodal encoder

Facial expression encoder: Based on the ResNet50 architecture, the facial expression model was trained on the mouse facial dataset and the corresponding emotion labels. The features were encoded as one-hot vectors, forming facial emotion feature matrices by concatenating the facial vectors across fixed frames. Let \(F_t \in \mathbb {R}^{d_f}\) denote the facial feature vector at frame \(t\), where \(d_f\) represents the dimensionality of the feature space (e.g., \(d_f = 2\) for one-hot encoding). The facial emotion feature matrix \(\textbf{F}\) is constructed by concatenating the vectors across \(n\) frames.

Posture encoder: The posture recognition features are defined by 9 key points, including the limbs, back, head, ears, and tail16. Let \(P_t \in \mathbb {R}^{2 \cdot 9}\) represent the posture feature vector at frame \(t\), where each keypoint has a corresponding \((x, y)\) coordinate. The posture feature matrix \(\textbf{P}\) is then constructed by concatenating these posture vectors across \(n\) frames. Each vector \(\textbf{P}_t \in \mathbb {R}^{18}\) captures the dynamic posture of the mouse, and the matrix \(\textbf{P}\) retains temporal information over time.

Trajectory encoder: Mouse trajectories were represented as 2D coordinate vectors. Let \(T_t \in \mathbb {R}^{2}\) denote the trajectory vector at frame \(t\), representing the position in the 2D space. The trajectory feature matrix \(\textbf{T}\) is constructed by concatenating the trajectory vectors across \(n\) frames. This matrix \(\textbf{T}\) captures the temporal dynamics of the mouse’s movement over time, with each \(\textbf{T}_t\) containing the 2D coordinates of the mouse’s position at frame \(t\).

The resulting encoded matrices derived from all three modalities (i.e., facial expressions, postures, and movement trajectories) were concatenated to form a unified multimodal encoding matrix, which was then input into the emotion classification model.

Multimodal emotion classification model

For emotion classification purposes, a transformer-based42 model was employed. The encoded matrices produced for facial expressions, postures, and movement trajectories were concatenated and weighted via self-attention mechanisms to enhance the effect of feature fusion. Let \(\textbf{F}, \textbf{P}, \textbf{T}\) represent the encoded matrices for facial expressions, postures, and movement trajectories, respectively. The concatenated feature vector \(\textbf{M}\) is formed by concatenating these matrices across their respective dimensions.

This unified multimodal feature matrix \(\textbf{M}\) is then weighted by the self-attention mechanism, which learns the importance of each modality. The self-attention mechanism is given by42,43:

The concatenated feature vector, after self-attention weighting, was passed to a BERT44 model to capture the complex relationships between the different modalities and model long-range dependencies. The final emotion classification results were output through a fully connected layer, with the softmax function generating predicted probabilities for the possible emotional states. The model was optimized using a cross-entropy loss function to obtain efficient and accurate predictions.

Training process

During the model training and inference processes, we used an NVIDIA RTX 4090 GPU (24 GB). The model training procedure was based on the PyTorch framework45.

Raining single-modality encoders

To ensure that effective features were extracted from each modality, we first trained separate models for recognizing facial expressions, postures, and trajectories, obtaining individual modality-specific encoders.

Facial Expression Encoder Training: The facial expression recognition model was designed as a classification network that maps a single-frame facial image of a mouse to a \(1 \times 2\) one-hot encoded vector representing two emotion categories. ResNet50 served as the backbone network and was optimized via the adaptive moment estimation (Adam)46 optimizer with an initial learning rate of \(1 \times 10^{-4}\) and a batch size of 8. The model was trained for 50 epochs using the cross-entropy loss function, which incorporates data augmentation techniques such as random rotation and flipping to enhance the generalizability of the model.

Posture Recognition Encoder Training: The posture recognition model was implemented via the DeepLabCut framework, which employs a deep pose estimation algorithm to track nine key points on the body of each mouse, generating an output consisting of \(1 \times 18\) coordinate vectors. DeepLabCut used a ResNet50-based feature extraction network and was optimized through supervised learning with the mean squared error (MSE) loss. The Adam optimizer with an initial learning rate of \(1 \times 10^{-4}\), a batch size of 8, and 20000 training iterations was adopted during the training process.

Trajectory Recognition Encoder Training: The trajectory recognition model, which is also based on DeepLabCut, was trained to detect the movement trajectory of each mouse within the experimental environment. The model identified and calibrated the position of each mouse by detecting the four corners of the enclosure, outputting a \(1 \times 2\) coordinate vector (x, y). The training process was similar to that of posture recognition, using a ResNet50 backbone; the Adam optimizer with an initial learning rate of \(1 \times 10^{-4}\), a batch size of 8, and 20000 training iterations; and the MSE loss as the objective function.

Multimodal fusion training

After training the individual modality-specific encoders, we concatenated the extracted features to form an \((2 + 18 + 2) \times n\) multimodal encoding matrix and fine-tune a BERT-based model for classifying the final emotions. The BERT model employed a transformer architecture for contextual modelling, and it was trained with the weighted Adam optimizer, an initial learning rate of \(1 \times 10^{-4}\), and a batch size of 8. The cross-entropy loss function was used for optimization, and an early stopping strategy was applied (terminating the training process if the validation loss did not decrease for five consecutive epochs). During inference, a sequence of n consecutive frames was fed into the three modality-specific encoders, and the extracted features were fused through the BERT model to produce the final emotion classification outcome.

Model evaluation and validation

To evaluate the performance of the multimodal emotion classification model, we used metrics such as accuracy, sensitivity and specificity. During the training process, 10-fold cross-validation was applied to assess the stability of the model. To validate the accuracy of the model, we used physiological gold standards, such as corticosterone levels or heart rates, to confirm the presence of fear responses. Fear typically induces significant changes in these physiological metrics, and comparing the predictions yielded by the model with physiological data provided an additional validation of its accuracy and robustness.

Ethical statement

All experimental protocols in this study were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Jilin University (IACUC permit number: SY202305300) in compliance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals: Eighth Edition and the Laboratory Animal - Guideline for ethical reviews of animal welfare (GB/T 35892-2018). All methods were reported in accordance with the “ARRIVE” guidelines.

Results

Accuracy comparison involving the multimodal emotion classification model

To evaluate the performance of the proposed multimodal emotion classification model, we compared its outputs with the trajectory analysis results obtained from an open field experiment, as well as the classification outcomes derived from three single-modal models (i.e., facial expressions, body postures, and movement trajectories), as shown in Table 1. The experimental results revealed that the accuracies of the single-modal models were relatively low, with the classification accuracies achieved for facial expressions, body postures, and movement trajectories being 73.3%, 78.3%, and 65.0%, respectively. In contrast, the emotion recognition results produced using trajectory analysis in the open field experiment yielded an accuracy of 93.3%. In comparison, the proposed multimodal fusion model, which jointly analysed facial expression, body posture, and movement trajectory information, significantly improved the attained accuracy, reaching 86.7%. This demonstrates the effectiveness of multimodal fusion in mouse emotion recognition tasks.

Ablation study concerning multimodal emotion recognition under different monitoring durations

The mouse emotion recognition accuracies achieved across different time windows of 3, 5, 10, and 15 seconds were compared in this study, as shown in Figure 2. The results indicated that the accuracy of the multimodal emotion recognition model stabilized after 10 seconds, ultimately reaching 86.7%. Similarly, the facial expression- and body posture-based emotion recognition models also stabilized after 10 seconds, with accuracies of 73.3% and 78.3%, respectively. In contrast, the accuracy of the movement trajectory recognition model continuously increased throughout the monitoring period, reaching 69.0% after 15 seconds.

Ablation study concerning multimodal emotion recognition under different frame sampling rates

The accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity of mouse emotion recognition results produced with frame sampling rates of 10, 20, 40, and 60 frames over a 10-second detection window were compared in this study, as shown in Figure 3. The results showed that the accuracy of the multimodal emotion recognition model remained relatively stable, with a slight increase between 10 and 40 frames, and eventually stabilized. Ultimately, the accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity of the model were found to stabilize at 86.7%, 83.4%, and 90.0%, respectively.

Discussion

The multimodal emotion recognition method proposed in this study successfully achieved efficient and accurate fear emotion monitoring in mice by combining facial expression, body posture, and movement trajectory data. The experimental results demonstrate the significant advantages of the multimodal model, particularly in terms of accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity.

First, although single-modal emotion recognition models have made progress in their respective domains, they still present certain limitations. The accuracy of the facial expression model was 73.3%, the body posture model achieved an accuracy of 78.3%, and the movement trajectory model reached 69.0%. Facial expressions, as forms of emotional expression, are influenced by the anatomical features of the face and viewing angle of each mouse, leading to instability, especially during rapid movements or in blind spots. Body posture analysis, which relies on a mouses limb movements, provides a good reflection of emotional changes. However, in corners of the arena, the missing coordinates of some body parts can yield reduced classification accuracy. Movement trajectory analysis captures a mouses spatial exploration behaviours, which, in fear contexts, become chaotic and difficult to accurately capture, leading to a decline in model performance. As a result, single-modal methods fail to provide sufficient information, limiting the accuracy of their emotion classification processes.

In comparison, the multimodal fusion method exhibits enhanced emotion recognition accuracy by combining various features derived from facial expressions, body postures, and movement trajectories, fully leveraging the complementary nature of different data sources. In this study, the accuracy of the multimodal emotion recognition model increased significantly to 86.7%. This result indicates that features from different modalities can complement each other, providing a more comprehensive representation of emotions. In particular, the use of a temporal-aware encoder for processing continuous frame data enabled the model to capture the dynamic changes exhibited by the emotional states of the mice, effectively integrating the temporal dependencies contained in posture and movement trajectories. Compared with the single-modal models, the multimodal model better reflected the multidimensional features of the changes in the emotional states of the mice, significantly enhancing the robustness and accuracy of emotion classification.

However, this study also has certain limitations. First, although the multimodal model achieved high accuracy, its performance was still influenced by the experimental conditions and the quality of the input data. For example, the angle and quality of the camera setup affect the accuracy of facial expression and body posture recognition tasks, particularly when a mouse moves quickly or when the camera angle is poor, which can lead to facial features being lost or misidentified. Although the study employed blank token padding to mitigate missing facial data, this approach did not fully eliminate the data losses caused by blind spots or rapid movements. Second, owing to the contextual awareness limitations of the BERT model, analysing long monitoring windows or high frame rates may lead to incomplete temporal perception, resulting in misclassification.

Future research could explore expanding the proposed approach to more diverse emotional recognition scenarios, with the aim of developing a comprehensive multimodal recognition model for detecting a full range of emotions. Additionally, extending the contextual awareness length of the classification model, as well as considering emotions beyond the set perceptual window, is crucial. This approach could effectively address the data loss caused by a mouse stopping its movement or facing away from the camera, enhancing the robustness and accuracy of the emotion recognition system.

The proposed multimodal framework introduces increased but manageable computational complexity compared to unimodal baselines. For the visual encoders, each ResNet50-based encoder requires \(O(C \times W \times H)\) operations per frame during inference, where C, W, H denote input channels, width and height respectively. Training complexity scales linearly with epochs E, batch size B, and sample size N, yielding \(O(E \times B \times N \times C \times W \times H)\) per modality.

For the multimodal fusion, The BERT-based fusion module adds \(O(N \times L^2)\) complexity during inference for sequence length N and hidden dimension L, with training complexity \(O(E \times B \times N \times L^2)\). The total complexity is:

The total complexity exceeds single-modal methods due to multi-encoder processing and transformer operations. However, this trade-off is necessary to achieve enhanced classification performance through complementary feature integration from facial expressions, posture dynamics, and motion trajectories, as demonstrated in our experiments.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author: chy@jlu.edu.cn.

References

Lee, E.-H., Park, J.-Y., Kwon, H.-J. & Han, P.-L. Repeated exposure with short-term behavioral stress resolves pre-existing stress-induced depressive-like behavior in mice. Nature Communications 12, 6682 (2021).

Dolensek, N., Gehrlach, D. A., Klein, A. S. & Gogolla, N. Facial expressions of emotion states and their neuronal correlates in mice. Science 368, 89–94 (2020).

Adjimann, T. S., Argañaraz, C. V. & Soiza-Reilly, M. Serotonin-related rodent models of early-life exposure relevant for neurodevelopmental vulnerability to psychiatric disorders. Translational psychiatry 11, 280 (2021).

Mock, E. D. et al. Discovery of a nape-pld inhibitor that modulates emotional behavior in mice. Nature chemical biology 16, 667–675 (2020).

Fu, H. et al. Fear arousal drives the renewal of active avoidance of hazards in construction sites: evidence from an animal behavior experiment in mice. Journal of Construction Engineering and Management 150, 04024146 (2024).

Klein, A. S., Dolensek, N., Weiand, C. & Gogolla, N. Fear balance is maintained by bodily feedback to the insular cortex in mice. Science 374, 1010–1015 (2021).

Ahn, S.-H. et al. Basal anxiety during an open field test is correlated with individual differences in contextually conditioned fear in mice. Animal Cells and Systems 17, 154–159 (2013).

Stiedl, O. & Spiess, J. Effect of tone-dependent fear conditioning on heart rate and behavior of c57bl/6n mice. Behavioral neuroscience 111, 703 (1997).

Vidal, A., Jha, S., Hassler, S., Price, T. & Busso, C. Face detection and grimace scale prediction of white furred mice. Machine Learning with Applications 8, 100312 (2022).

Zhang, H. et al. The recovery trajectory of adolescent social defeat stress-induced behavioral, 1h-mrs metabolites and myelin changes in balb/c mice. Scientific reports 6, 27906 (2016).

Kendall, A., Grimes, M. & Cipolla, R. Posenet: A convolutional network for real-time 6-dof camera relocalization. In Proceedings of the IEEE international conference on computer vision, 2938–2946 (2015).

Nguyen, D. et al. Deep auto-encoders with sequential learning for multimodal dimensional emotion recognition. IEEE Transactions on Multimedia 24, 1313–1324 (2021).

van der Goot, M. H. et al. An individual based, multidimensional approach to identify emotional reactivity profiles in inbred mice. Journal of Neuroscience Methods 343, 108810 (2020).

Andresen, N. et al. Towards a fully automated surveillance of well-being status in laboratory mice using deep learning: Starting with facial expression analysis. Plos one 15, e0228059 (2020).

Sheppard, K. et al. Gait-level analysis of mouse open field behavior using deep learning-based pose estimation. BioRxiv 2020–12 (2020).

Gabriel, C. J. et al. Behaviordepot is a simple, flexible tool for automated behavioral detection based on markerless pose tracking. Elife 11, e74314 (2022).

Martınez, G. H. Openpose: Whole-body pose estimation. Ph.D. thesis, Carnegie Mellon University Pittsburgh, PA, USA (2019).

Mathis, A. et al. Deeplabcut: markerless pose estimation of user-defined body parts with deep learning. Nature neuroscience 21, 1281–1289 (2018).

Sun, G. et al. Deepbhvtracking: a novel behavior tracking method for laboratory animals based on deep learning. Frontiers in behavioral neuroscience 15, 750894 (2021).

Paul, E. S., Harding, E. J. & Mendl, M. Measuring emotional processes in animals: the utility of a cognitive approach. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 29, 469–491. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2005.01.002 (2005).

Reefmann, N., Wechsler, B. & Gygax, L. Behavioural and physiological assessment of positive and negative emotion in sheep. Animal Behaviour 78, 651–659. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anbehav.2009.06.015 (2009).

Mills, D. S. Perspectives on assessing the emotional behavior of animals with behavior problems. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences 16, 66–72, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cobeha.2017.04.002 (2017). Comparative cognition.

Mechiel Korte, S. & De Boer, S. F. A robust animal model of state anxiety: fear-potentiated behaviour in the elevated plus-maze. European Journal of Pharmacology 463, 163–175, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0014-2999(03)01279-2 (2003). Animal Models of Anxiety Disorders.

Biedermann, S. V. et al. An elevated plus-maze in mixed reality for studying human anxiety-related behavior. BMC biology 15, 1–13 (2017).

Pavesi, E., Canteras, N. S. & Carobrez, A. P. Acquisition of pavlovian fear conditioning using \(\beta\)-adrenoceptor activation of the dorsal premammillary nucleus as an unconditioned stimulus to mimic live predator-threat exposure. Neuropsychopharmacology 36, 926–939 (2011).

Mandillo, S. et al. Reliability, robustness, and reproducibility in mouse behavioral phenotyping: a cross-laboratory study. Physiological genomics 34, 243–255 (2008).

Katmah, R. et al. A review on mental stress assessment methods using eeg signals. Sensors 21, 5043 (2021).

Teo, J. T., Johnstone, S. J. & Thomas, S. J. Use of portable devices to measure brain and heart activity during relaxation and comparative conditions: Electroencephalogram, heart rate variability, and correlations with self-report psychological measures. International Journal of Psychophysiology 189, 1–10 (2023).

Broomé, S. et al. Going deeper than tracking: A survey of computer-vision based recognition of animal pain and emotions. International Journal of Computer Vision 131, 572–590 (2023).

Chiavaccini, L., Gupta, A. & Chiavaccini, G. From facial expressions to algorithms: a narrative review of animal pain recognition technologies. Frontiers in Veterinary Science 11, 1436795 (2024).

Descovich, K. A. et al. Facial expression: An under-utilized tool for the assessment of welfare in mammals. ALTEX-Alternatives to animal experimentation 34, 409–429 (2017).

Ehret, G. Characteristics of vocalization in adult mice. In Handbook of behavioral neuroscience, vol. 25, 187–195 (Elsevier, 2018).

Jabarin, R., Netser, S. & Wagner, S. Beyond the three-chamber test: toward a multimodal and objective assessment of social behavior in rodents. Molecular Autism 13, 41 (2022).

Yu, D., Bao, L. & Yin, B. Emotional contagion in rodents: A comprehensive exploration of mechanisms and multimodal perspectives. Behavioural Processes 105008 (2024).

Zhu, X. et al. A review of key technologies for emotion analysis using multimodal information. Cognitive Computation 1–27 (2024).

Bali, A. & Jaggi, A. S. Electric foot shock stress: a useful tool in neuropsychiatric studies. Reviews in the Neurosciences 26, 655–677 (2015).

Valentinuzzi, V. S. et al. Automated measurement of mouse freezing behavior and its use for quantitative trait locus analysis of contextual fear conditioning in (balb/cj\(\times\) c57bl/6j) f2 mice. Learning & memory 5, 391–403 (1998).

Klemenhagen, K. C., Gordon, J. A., David, D. J., Hen, R. & Gross, C. T. Increased fear response to contextual cues in mice lacking the 5-ht1a receptor. Neuropsychopharmacology 31, 101–111 (2006).

Daldrup, T. et al. Expression of freezing and fear-potentiated startle during sustained fear in mice. Genes, Brain and Behavior 14, 281–291 (2015).

He, K., Zhang, X., Ren, S. & Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 770–778 (2016).

Ren, S., He, K., Girshick, R. & Sun, J. Faster r-cnn: Towards real-time object detection with region proposal networks. IEEE transactions on pattern analysis and machine intelligence 39, 1137–1149 (2016).

Vaswani, A. Attention is all you need. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (2017).

Jin, B. et al. Simulated multimodal deep facial diagnosis. Expert Systems with Applications 252, 123881 (2024).

Devlin, J. Bert: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. arXiv preprint arXiv:1810.04805 (2018).

Jin, B., Cruz, L. & Gonçalves, N. Deep facial diagnosis: deep transfer learning from face recognition to facial diagnosis. IEEE Access 8, 123649–123661 (2020).

Kingma, D. P. Adam: A method for stochastic optimization. arXiv preprint arXiv:1412.6980 (2014).

Gould, T. D., Dao, D. T. & Kovacsics, C. E. The open field test. Mood and anxiety related phenotypes in mice: Characterization using behavioral tests 1–20 (2009).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Jilin Province Science and Technology Development Project (grant no. 20230505035ZP). We thank SNAS website for its linguistic assistance during the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Hao Wang was responsible for writing the manuscript and designing the model structure. Zhanpeng Shi designed the animal experiments and collected the raw data. Ruijie Hu assisted in the completion and data collection processes of the animal experiments. Xinyi Wang designed the ablation experiments. Jian Chen provided guidance for designing the animal experiments. Haoyuan Che provided guidance for designing the multimodal algorithm and writing the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, H., Shi, Z., Hu, R. et al. Real-time fear emotion recognition in mice based on multimodal data fusion. Sci Rep 15, 11797 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-95483-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-95483-z