Abstract

In this paper, a pair of quantum states are constructed based on an orthogonal array and further generalized to multi-body quantum systems. Subsequently, a novel physical process is designed, which is aimed at effectively masking quantum states within multipartite quantum systems. According to this masker, a new authenticable quantum secret sharing scheme is proposed, which can realize a class of special access structures. In the distribution phase, an unknown quantum state is shared safely among multiple participants, and this secret quantum state is embedded into a multi-particle entangled state using the masking approach. In the reconstruction phase, a series of precisely designed measurements and corresponding unitary operations are performed by the participants in the authorized set to restore the original information quantum state. To ensure the security of the scheme, the security analysis of five major types of quantum attacks is conducted. Finally, when compared with other quantum secret sharing schemes based on entangled states, the proposed scheme is found to be not only more flexible but also easier to implement based on existing quantum computing cloud platforms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Secret sharing, as a key research direction in the field, has demonstrated its effectiveness in numerous applications such as privacy protection and digital forensics. In 1979, Shamir1 and Blakley2 independently introduced the concept of secret sharing based on different mathematical perspectives, which significantly contributed to the field of information security. Therefore, Shamir’s and Blakley’s work has not only had a profound impact in academia but has also offered crucial technical support for information confidentiality and secure transmission in practical applications.

With the advent of quantum information science and the progression of quantum communication technologies, some researchers have extended the traditional secret sharing protocols into the quantum realm3,4,5,6. This has given rise to quantum secret sharing (QSS) protocols, which serve as the quantum analogue to the classical secret sharing problem. The safety of the QSS is guaranteed by basic principles of quantum mechanics, such as the Heisenberg uncertainty principle and the quantum no-cloning theorem. QSS schemes are typically classified into two distinct categories. The first category involves the shared secret being an unknown quantum state, where the information is encoded directly into the quantum properties of particles. The second category pertains to scenarios where the shared secret is classical information, which is transmuted into a quantum state for the purposes of distribution and reconstruction. In both cases, the participants joined a quantum network system and built quantum communication channels between the dealers and the participants. This facilitates the transmission and reconstruction of the secret in a manner that is inherently secure against eavesdropping and other forms of quantum attacks.

In 1999, Hillery et al.3 used the properties of three-qubit or four-qubit entangled GHZ states to design the first QSS protocol. Building upon this seminal contribution, Xiao et al.7, in 2004, expanded the scope of QSS proposed by Hillery et al. to encompass arbitrary multipartite entangled states. By extending the principles of QSS to multipartite entanglement, Xiao et al. opened up new avenues for the robust and scalable distribution of quantum information, thereby reinforcing the security and reliability of quantum communication networks. From then on, various QSS schemes have been proposed8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25. Among many quantum secret sharing protocols, the phenomenon of quantum entanglement stands as a cornerstone, enabling the secure transmission and processing of information in ways that are fundamentally inaccessible through classical means. For example, Mansour et al.26 developed a (n, n) threshold quantum secret sharing scheme using entangled multi-qudit states. Zhang et al.27 proposed two special QSS protocols with the multiparty entangled states to realize the (n, n) threshold. Bai et al.28 proposed a verifiable threshold quantum secret sharing protocol with d-dimensional GHZ state to realize the (t, n) threshold. Rahaman et al.29 offered a quantum secret sharing scheme based on local distinguishability. Bai et al.30 proposed a quantum secret sharing scheme based on the distinguishability of some orthogonal multipartite entangled states in d-dimensional system under restricted local operations and classical communication. Houshmand et al.31 presented an efficient controlled semi-quantum secret sharing protocol with entangled state. Li et al.32 focused on the quantum secret sharing scheme through designing a special entangled state by resorting to monotone span program. Li et al.33 proposed an authenticable dynamic quantum multi-secret sharing scheme based on the Chinese remainder theorem and GHZ state.

Through the above protocol, it is not difficult to find that quantum entangled states can be used as an important tool for the construction of quantum secret sharing schemes, which can provide rich theoretical resources. Using the quantum correlation of a bipartite entangled state, classical information can be hidden. In 2018, Modi et al.35 showed that quantum information can be masked in the quantum correlations of bipartite composite systems rather than the subsystems. The masking process is completed by unitary operations, which it can map single-particle states into entangled states. Afterwards, some researchers have given relevant results on the masking of quantum information36,37,38,39,40. In particular, Li et al.38 proposed quantum information masking schemes using multi-particle entangled states. In 2024, Wang et al.41 explored the possibility of masking the quantum information in multipartite systems based on the generator matrices and stabilizer codes. Furthermore, Bai et al.42 introduced a novel method for achieving quantum information masking in multipartite systems utilizing a Fourier matrix and Hadamard matrix.

Quantum information masking holds the potential to revolutionize entanglement-based quantum secret sharing schemes and paves the way for advanced quantum communication protocols. For example, Bai et al.43 proposed a quantum secret sharing scheme based on quantum information masking to realize a class of special hypergraph access structures. Drawing on the concept of quantum information masking, this paper initially presents the method of masking quantum states utilizing an orthogonal array, and subsequently carries out the process of mapping these quantum states into multipartite quantum systems. Then, we construct an authenticable quantum state sharing scheme based on quantum information masking. For our scheme, it can implement a special class of access structures. Furthermore, the security of the scheme against five primary quantum attacks is analyzed, namely the man-in-the-middle attack, intercept-and-resend attack, entangle-and-measure attack, participant attack and collective attack. Finally, a comparison is made between this scheme and existing quantum secret sharing schemes.

The organization of this paper is as follows. In Section “Results”, we mask the qubit into multipartite quantum systems. In Section “Quantum state sharing scheme”, we give a special class of access structures and propose the quantum secret sharing scheme based on the quantum information masking. In Section “Comparison”, we analyze the security of our scheme and compare it with existing schemes. Finally, the conclusion is given in Section “Conclusions”.

Results

Masking quantum states into multipartite quantum systems

In this section, we mainly give some necessary concepts and principles about the masking of quantum information, see Refs.35,38. In Refs.35,38, the authors proposed the concepts of quantum information masking.

Definition 1

(Ref.35) An operation \({\mathscr {F}}\) is said to mask quantum information contained in states \(\{{|{a_k}\rangle }_{A_1}\in {H}_{A_1}\}\) by mapping them to states \(\{{|{\Psi _k}\rangle }\in {H}_{A_1}\otimes {H}_{A_2}\}\) such that all marginal states of \({|{\Psi _k}\rangle }\) are the same, i.e.,

Definition 2

(Ref. 38) An operation \({\mathscr {F}}\) is said to mask quantum information contained in states \(\{{|{a_k}\rangle }_{A_1}\in {H}_{A_1}\}\) by mapping them to states \(\{{|{\Psi _k}\rangle }\in \bigotimes _{j=1}^n {H}_{A_j}\}\) such that all marginal states of \({|{\Psi _k}\rangle }\) are the same, i.e.,

where \({\widehat{A}}_j\) denotes the set \(\{A_1,A_2,\cdots ,A_n\}\setminus \{A_j\}\).

In Ref.42, we introduced a novel method for achieving quantum information masking in multipartite systems utilizing a Fourier matrix and Hadamard matrix. Next, the orthogonal arrays are introduced in this context.

Definition 3

(Ref. 44) Let A be an array of dimensions \(r\times N\) whose elements are drawn from a set \(S = \{s_1,s_2,\cdots ,s_d\}\). If every \(r\times k\) subarray of A contains each k-tuple of symbols from S with equal frequency, then A is said to be an orthogonal array, denoted as OA(r, N, d, k).

In order to construct quantum state sharing schemes, a special class of orthogonal arrays is considered in this paper. Consequently, a \(2^3\)-order Hadamard matrix is presented, as follows:

For Eq. (1), the first column and any two of the remaining columns in the matrix \(H_{2^3}\) are removed, and all the elements of 1 are replaced with 0, while 1 is replaced with 1. Hence we get an orthogonal array. Therefore, we take deleting the first two and last columns as an example to obtain an orthogonal array OA(8, 5, 2, 2), where it is denoted by

Based on OA(8, 5, 2, 2) in Eq. (2), the quantum states \({|{\phi _0}\rangle }\) and \({|{\phi _1}\rangle }\) are constructed and denoted by

Hence, the following theorem is obtained.

Theorem 1

For \({|{\phi _0}\rangle }\) and \({|{\phi _1}\rangle }\) generated in Eq. (3), there exists that all the states \(\alpha {|{0}\rangle }+\beta {|{1}\rangle }\) can be masked into \({|{\phi }\rangle }=\alpha {|{\phi _0}\rangle }+\beta {|{\phi _1}\rangle }\), where \(|\alpha |^2+|\beta |^2=1\).

This proof process is relatively simple. Through Definition 2, we only need to calculate that the state of each subsystem is in the maximal mixed state, i.e \(\rho _{A_1}=\rho _{A_2}=\rho _{A_3}=\rho _{A_4}=\rho _{A_5}=\frac{I}{2}.\)

Furthermore, we use the quantum states \({|{\phi _0}\rangle }\) and \({|{\phi _1}\rangle }\) to construct a pair of the entangled states \({|{\psi _0}\rangle }\) and \({|{\psi _1}\rangle }\) with n quantum systems in Eqs. (4) and (5). Furthermore, a quantum circuit diagram for generating the quantum state \({|{\psi _0}\rangle }\) is as shown in Fig. 1. By the quantum states \({|{\psi _0}\rangle }\) and \({|{\psi _1}\rangle }\), the following physical process \({\mathscr {U}}\) is constructed, namely,

where \(r_i\ge 2\ (i=1,2)\) and \(3+r_1+r_2=n\).

Theorem 2

For \({|{\psi _0}\rangle }\) and \({|{\psi _1}\rangle }\) generated Eqs. (4) and (5), there exists that all the states \(\alpha {|{0}\rangle }+\beta {|{1}\rangle }\) can be masked into \({|{\Psi }\rangle }=\alpha {|{\psi _0}\rangle }+\beta {|{\psi _1}\rangle }\), where \(|\alpha |^2+|\beta |^2=1\) and the state \({|{\Psi }\rangle }\) is denoted by

Through Definition 2, we can easily calculate the partial trace for each subsystem \({A}_j\) of the quantum state \({|{\Psi }\rangle }{\langle {\Psi }|}\), i.e.,

Therefore, all the quantum states \(\alpha {|{0}\rangle }+\beta {|{1}\rangle }\) can be masked thought the quantum state \({|{\Psi }\rangle }\) in Eq. (6).

Quantum state sharing scheme

In this section, we initially delineate the access structure as implemented by our construction scheme. Subsequently, we present the quantum state sharing protocol based on quantum information masking.

Access structure

Assuming that Alice wants to share quantum state among n participants, \(\{P_{11},\cdots ,P_{1l_1},P_{21},\cdots , P_{2l_2},\cdots ,P_{m1}, \cdots ,P_{ml_m}\}\), and she divides these participants into m groups, i.e.,

where \(l_1+l_2+\cdots +l_m=n\).

Furthermore, the following access structure \({\widetilde{\Gamma }}\) is constructed and denoted by

In this paper, we construct a quantum state sharing scheme based on quantum information masking to implement a special access structure \(\Gamma\). The protocol separates these n participants in four groups, namely,

where \(2+t_3+t_4=n\). Therefore, \(\Gamma\) is denoted by

Our proposed scheme

In this section, we construct a quantum state sharing scheme to implement the access structure \(\Gamma\) in Eq. (8). For the sake of expression convenience, the participants in the four groups are renumbered and denoted as

where \(t_3=r-2\) and \(t_4=n-r-1\). Hence, \(\Gamma\) is changed to (see Fig. 2)

Identity authentication phase. To resist impersonation attacks, Alice and each participant \(P_j\) use their personal identification number (PIN) to prepare a single photon sequence for mutual identity authentication (see Fig. 3).

Step I.1 Alice generates a one-time \(\hbox {PIN}_j\) and sends to \(P_j\) via quantum secure direct communication (QSDC) or a face-to-face way. At the same time, the participant \(P_j\) generates \(\hbox {PIN}_{P_j}\) and sends it to Alice in the same way. The form of \(\hbox {PIN}_j\) and \(\hbox {PIN}_{P_j}\) are as follows:

where \(\text {PIN}_j^i, \text {PIN}_{P_j}^i \in \{00, 01, 10, 11\}\), \(i=1,2,\cdots ,l\) and the length of \(\text {PIN}_j\) and \(\text {PIN}_{P_j}\) are 2l.

Step I.2 \(P_j\) generates l authentication photons as a token based on \(\text {PIN}_{P_j}\) and performs operations according to \(\hbox {PIN}_j\). Then \(P_j\) transmits the token to Alice. Here, the guidelines for photon generation in the protocol are presented in Table 1, and the operational rules are specified in Table 2.

Step I.3 Upon receiving the token, Alice executes a unitary operation on each photon, following the instructions of \(\hbox {PIN}_j\) and employs the measurement basis by \(\hbox {PIN}_{P_j}\) for each particle. If Alice’s measurement results align with the indication of \(\hbox {PIN}_{P_j}\), she confirms \(P_j\) is legal. Otherwise, she issues an alert regarding the illegitimacy of \(P_j\)’s identity.

Distribution share phase. Assuming that the secret \({|{s}\rangle }=\alpha {|{0}\rangle }+\beta {|{1}\rangle }\) is an arbitrary 2-dimensional quantum state. In order to share the distribution, Alice selects a masker \({\mathscr {F}}\) and defines a unitary operator \(U_{{\mathscr {F}}}\) on the system of the secret \({|{s}\rangle }\) plus \(n-1\) ancillary systems \(A_2,A_3,\cdots ,A_n\). Therefore,

where \({|{\Psi _{s}}\rangle }=\alpha {|{\psi _0}\rangle }+\beta {|{\psi _1}\rangle }\) in Eq. (6).

Furthermore, Alice uses the checking photon technique to guarantee the security of transmission and randomly chooses some checking single photons from the following set \(Z=\{{|{0}\rangle },{|{1}\rangle }\}\) or \(X=\{{|{+}\rangle }=\frac{{|{0}\rangle }+{|{1}\rangle }}{\sqrt{2}},{|{-}\rangle }=\frac{{|{0}\rangle }-{|{1}\rangle }}{\sqrt{2}}\}\). These photons randomly selected from X or Z can be represented as

where \(p^i_k\) indicates the particle selected from X or Z and \(k=1,2,\cdots ,r,r+2,\cdots ,n.\)

At last, Alice retains the \((r+1)\)-th particle in the quantum state \({|{\Psi _{s}}\rangle }\) and inserts the k-th particle of \({|{\Psi _{s}}\rangle }\) into the sequence \(C_k\) and obtains new sequences \(S_1,\cdots ,S_r,S_{r+2},\cdots ,S_n\). Then she sends the sequence \(S_k\) to the participant \(P_k\) (see Fig. 4).

Upon verification that participants \(P_1,\cdots ,P_r,P_{r+2},\cdots , P_n\) have successfully received their respective sequences, Alice announces the coordinates for the checking photons within each sequence. Then all participants randomly choose the Z basis or X basis to measure these corresponding checking photons and send their measurements to Alice. Utilizing the data submitted by all participants, Alice calculates the error rate. If the error rate is higher than threshold value, Alice is compelled to terminate the protocol.

Reconstruction secret phase. The secret \({|{s}\rangle }\) can be reconstructed from any authorized set in \(\Gamma '\). These participants can carry out several measurements on their particles and then utilize the classical communication to tell their results to the others. For convenience, we take the authorized set \(\{P_1P_2P_3P_{r+2}\}\) as an example, and the other cases can be similarly analyzed.

Step R.1 The participant \(P_3\) carries out several measurements on his particle in \({|{\Psi _s}\rangle }\) under the basis of \(\{|0\rangle ,|1\rangle \}\). At the same time, the remaining participants can get the following collapse states on their own particles. For convenience, we omit the correlative coefficients.

-

(1)

If the measurement by \(P_3\) is \(|0\rangle\), then the quantum state \({|{\Psi _s}\rangle }\) can collapse to \({|{\Psi ^0_s}\rangle }\), where \({|{\Psi ^0_s}\rangle }\) is denoted by

$$\begin{aligned} {|{\Psi ^0_s}\rangle }= & (\alpha {|{00}\rangle }+\beta {|{11}\rangle })_{12}{|{00\cdots 0}\rangle }_{{\bar{G}}_3}{|{0}\rangle }_{r+1}{|{00\cdots 0}\rangle }_{{\bar{G}}_4}+(\alpha {|{01}\rangle }+\beta {|{10}\rangle })_{12}{|{00\cdots 0}\rangle }_{{\bar{G}}_3}{|{1}\rangle }_{r+1}{|{00\cdots 0}\rangle }_{{\bar{G}}_4}\nonumber \\ & \quad +(\alpha {|{10}\rangle }+\beta {|{01}\rangle })_{12}{|{00\cdots 0}\rangle }_{{\bar{G}}_3}{|{1}\rangle }_{r+1}{|{11\cdots 1}\rangle }_{{\bar{G}}_4}+(\alpha {|{11}\rangle }+\beta {|{00}\rangle })_{12}{|{00\cdots 0}\rangle }_{{\bar{G}}_3}{|{0}\rangle }_{r+1}{|{11\cdots 1}\rangle }_{{\bar{G}}_4}. \end{aligned}$$(11) -

(2)

If the measurement by \(P_3\) is \(|1\rangle\), then the quantum state \({|{\Psi _s}\rangle }\) can collapse to \({|{\Psi ^1_s}\rangle }\), where \({|{\Psi ^1_s}\rangle }\) is denoted by

$$\begin{aligned} {|{\Psi ^1_s}\rangle }= & (\alpha {|{00}\rangle }+\beta {|{11}\rangle })_{12}{|{11\cdots 1}\rangle }_{{\bar{G}}_3}{|{1}\rangle }_{r+1}{|{11\cdots 1}\rangle }_{{\bar{G}}_4}+(\alpha {|{01}\rangle }+\beta {|{10}\rangle })_{12}{|{11\cdots 1}\rangle }_{{\bar{G}}_3}{|{0}\rangle }_{r+1}{|{11\cdots 1}\rangle }_{{\bar{G}}_4}\nonumber \\ & \quad +(\alpha {|{10}\rangle }+\beta {|{01}\rangle })_{12}{|{11\cdots 1}\rangle }_{{\bar{G}}_3}{|{0}\rangle }_{r+1}{|{00\cdots 0}\rangle }_{{\bar{G}}_4}+(\alpha {|{11}\rangle }+\beta {|{00}\rangle })_{12}{|{11\cdots 1}\rangle }_{{\bar{G}}_3}{|{1}\rangle }_{r+1}{|{00\cdots 0}\rangle }_{{\bar{G}}_4}. \end{aligned}$$(12)

Step R.2 The participant \(P_{r+2}\) measures the quantum state \({|{\Psi ^0_s}\rangle }\) or \({|{\Psi ^1_s}\rangle }\) with a computational basis \(\{|0\rangle ,|1\rangle \}\).

-

(1)

If the measurement is \(|0\rangle\), then the quantum state \({|{\Psi ^0_s}\rangle }\) (\({|{\Psi ^1_s}\rangle }\)) can collapse to \({|{\Psi ^{00}_s}\rangle }\) (\({|{\Psi ^{10}_s}\rangle }\)), where \({|{\Psi ^{00}_s}\rangle }\) and \({|{\Psi ^{10}_s}\rangle }\) are denoted by

$$\begin{aligned} {|{\Psi ^{00}_s}\rangle }= & (\alpha {|{00}\rangle }+\beta {|{11}\rangle })_{12}{|{00\cdots 0}\rangle }_{{\bar{G}}_3}{|{0}\rangle }_{r+1}{|{00\cdots 0}\rangle }_{{\bar{G}}_4}+(\alpha {|{01}\rangle }+\beta {|{10}\rangle })_{12}{|{00\cdots 0}\rangle }_{{\bar{G}}_3}{|{1}\rangle }_{r+1}{|{00\cdots 0}\rangle }_{{\bar{G}}_4},\nonumber \\ {|{\Psi ^{10}_s}\rangle }= & (\alpha {|{10}\rangle }+\beta {|{01}\rangle })_{12}{|{11\cdots 1}\rangle }_{{\bar{G}}_3}{|{0}\rangle }_{r+1}{|{00\cdots 0}\rangle }_{{\bar{G}}_4}+(\alpha {|{11}\rangle }+\beta {|{00}\rangle })_{12}{|{11\cdots 1}\rangle }_{{\bar{G}}_3}{|{1}\rangle }_{r+1}{|{00\cdots 0}\rangle }_{{\bar{G}}_4}. \end{aligned}$$(13) -

(2)

If the measurement is \(|1\rangle\), then the quantum state \({|{\Psi ^0_s}\rangle }\) (\({|{\Psi ^1_s}\rangle }\)) can collapse to \({|{\Psi ^{01}_s}\rangle }\) (\({|{\Psi ^{11}_s}\rangle }\)), where \({|{\Psi ^{01}_s}\rangle }\) and \({|{\Psi ^{11}_s}\rangle }\) are denoted by

$$\begin{aligned} {|{\Psi ^{01}_s}\rangle }= & (\alpha {|{10}\rangle }+\beta {|{01}\rangle })_{12}{|{00\cdots 0}\rangle }_{{\bar{G}}_3}{|{1}\rangle }_{r+1}{|{11\cdots 1}\rangle }_{{\bar{G}}_4}+(\alpha {|{11}\rangle }+\beta {|{00}\rangle })_{12}{|{00\cdots 0}\rangle }_{{\bar{G}}_3}{|{0}\rangle }_{r+1}{|{11\cdots 1}\rangle }_{{\bar{G}}_4}\nonumber ,\\ {|{\Psi ^{11}_s}\rangle }= & (\alpha {|{00}\rangle }+\beta {|{11}\rangle })_{12}{|{11\cdots 1}\rangle }_{{\bar{G}}_3}{|{1}\rangle }_{r+1}{|{11\cdots 1}\rangle }_{{\bar{G}}_4}+(\alpha {|{01}\rangle }+\beta {|{10}\rangle })_{12}{|{11\cdots 1}\rangle }_{{\bar{G}}_3}{|{0}\rangle }_{r+1}{|{11\cdots 1}\rangle }_{{\bar{G}}_4}. \end{aligned}$$(14)

Step R.3 The participant \(P_1\) cooperates with \(P_2\), and they carry their own particles to the same laboratory for a controlled-NOT (CNOT) gate, where the particles in \(P_1\)’s hand serve as control bits and the particles in \(P_2\) as target bits. Therefore, these states in Eqs. (13) and (14) are changed to

Step R.4 The participant \(P_{2}\) uses the computational basis \(\{|0\rangle ,|1\rangle \}\) to measure the quantum state \({|{\hat{\Psi }^{00}_s}\rangle }\), \({|{\hat{\Psi }^{10}_s}\rangle }\), \({|{\hat{\Psi }^{01}_s}\rangle }\) and \({|{\hat{\Psi }^{11}_s}\rangle }\) respectively.

-

(1)

If the measurement is \(|0\rangle\), then these quantum states can collapse into

$$\begin{aligned} \left\{ \begin{array}{l} {|{\hat{\Psi }^{00}_s}\rangle }\mapsto {|{\Psi ^{000}_s}\rangle }=(\alpha {|{0}\rangle }+\beta {|{1}\rangle })_{1}{|{0}\rangle }_2{|{00\cdots 0}\rangle }_{{\bar{G}}_3}{|{0}\rangle }_{r+1}{|{00\cdots 0}\rangle }_{{\bar{G}}_4},\\ \\ {|{\hat{\Psi }^{10}_s}\rangle }\mapsto {|{\Psi ^{100}_s}\rangle }=(\alpha {|{1}\rangle }+\beta {|{0}\rangle })_{1}{|{0}\rangle }_2{|{11\cdots 1}\rangle }_{{\bar{G}}_3}{|{1}\rangle }_{r+1}{|{00\cdots 0}\rangle }_{{\bar{G}}_4},\\ \\ {|{\hat{\Psi }^{01}_s}\rangle }\mapsto {|{\Psi ^{010}_s}\rangle }=(\alpha {|{1}\rangle }+\beta {|{0}\rangle })_{1}{|{0}\rangle }_2{|{00\cdots 0}\rangle }_{{\bar{G}}_3}{|{0}\rangle }_{r+1}{|{11\cdots 1}\rangle }_{{\bar{G}}_4},\\ \\ {|{\hat{\Psi }^{11}_s}\rangle }\mapsto {|{\Psi ^{110}_s}\rangle }=(\alpha {|{0}\rangle }+\beta {|{1}\rangle })_{1}{|{0}\rangle }_2{|{11\cdots 1}\rangle }_{{\bar{G}}_3}{|{1}\rangle }_{r+1}{|{11\cdots 1}\rangle }_{{\bar{G}}_4}. \end{array}\right. \end{aligned}$$(16) -

(2)

If the measurement is \(|1\rangle\), then these quantum states can collapse into

$$\begin{aligned} \left\{ \begin{array}{l} {|{\hat{\Psi }^{00}_s}\rangle }\mapsto {|{\Psi ^{001}_s}\rangle }=(\alpha {|{0}\rangle }+\beta {|{1}\rangle })_{1}{|{1}\rangle }_2{|{00\cdots 0}\rangle }_{{\bar{G}}_3}{|{1}\rangle }_{r+1}{|{00\cdots 0}\rangle }_{{\bar{G}}_4},\\ \\ {|{\hat{\Psi }^{10}_s}\rangle }\mapsto {|{\Psi ^{101}_s}\rangle }=(\alpha {|{1}\rangle }+\beta {|{0}\rangle })_{1}{|{1}\rangle }_{2}{|{11\cdots 1}\rangle }_{{\bar{G}}_3}{|{0}\rangle }_{r+1}{|{00\cdots 0}\rangle }_{{\bar{G}}_4},\\ \\ {|{\hat{\Psi }^{01}_s}\rangle }\mapsto {|{\Psi ^{011}_s}\rangle }=(\alpha {|{1}\rangle }+\beta {|{0}\rangle })_{1}{|{1}\rangle }_2{|{00\cdots 0}\rangle }_{{\bar{G}}_3}{|{1}\rangle }_{r+1}{|{11\cdots 1}\rangle }_{{\bar{G}}_4},\\ \\ {|{\hat{\Psi }^{11}_s}\rangle }\mapsto {|{\Psi ^{111}_s}\rangle }=(\alpha {|{0}\rangle }+\beta {|{1}\rangle })_{1}{|{1}\rangle }_2{|{11\cdots 1}\rangle }_{{\bar{G}}_3}{|{0}\rangle }_{r+1}{|{11\cdots 1}\rangle }_{{\bar{G}}_4}. \end{array}\right. \end{aligned}$$(17)

According to the measurements of the three participants \(\{P_3,P_{r+2},P_{2}\}\), \(P_1\) performs the following operations, as shown in Table 3. Therefore, \(P_1\) can recover the original quantum state \(\alpha {|{0}\rangle }+\beta {|{1}\rangle }\).

Example 1

In this example, we consider the case containing 8 participants and divide these participants into four groups, denoted as \(\bar{G}_1=\{P_{1}\},\bar{G}_2=\{P_{2}\},\bar{G}_3=\{P_{3},P_4,P_{5}\}, \bar{G}_4=\{P_{7},P_8,P_{9}\}\). Therefore, in this scheme, the following access structure \(\Gamma\) can be implemented, where

Alice masks the secret \({|{s}\rangle }=\alpha {|{0}\rangle }+\beta {|{1}\rangle }\) with the quantum state \({|{\phi _s}\rangle }\), where

The quantum state \({|{\phi _s}\rangle }\) can be implemented with a quantum circuit diagram, where \(R_Y(\theta )=\left( \begin{array}{cc} \cos \frac{\theta }{2} & \sin \frac{\theta }{2} \\ \sin \frac{\theta }{2} & \cos \frac{\theta }{2} \\ \end{array} \right)\) in Fig. 5. To facilitate the simulation of the following circuit diagram, we take \(\theta =1.56\) and obtain a probability bar graph for generating the quantum state \({|{\phi _s}\rangle }\), as shown in Fig. 6.

Alice inserts the i-th particle of \({|{\phi _s}\rangle }\) into the checking sequence and sends the sequence to the participant \(P_i\ (i=1,2,3,4,5,7,8,9)\). Alice uses the decoy particles to check the security of the channel. If it is secure, then the participants perform the secret recovery.

For convenience, the authorized set \(\{P_1P_2P_3P_8\}\) is taken as an example. The specific recovery process is described as follows:

-

(1)

These participants, \(P_3\) and \(P_8\), measure their particles in the hand with computational base \(\{{|{0}\rangle },{|{1}\rangle }\}\). Thus, the quantum state \({|{\phi _s}\rangle }\) collapses so that the 1st, 2nd, 6th system is in a product state with the 3rd, 4th, 5th, 7th, 8th, 9th system.

-

(2)

The participant \(P_1\) cooperates with \(P_2\) using a controlled-NOT gate, where the particles in \(P_1\)’s hand serve as control bits and the particles in \(P_2\) as target bits. Then, \(P_2\) measures his particles with computational base \(\{{|{0}\rangle },{|{1}\rangle }\}\).

-

(3)

Based on the measurements by \(P_3,P_{8}\), \(P_1\) performs the following operations, as shown in Table 4.

-

(4)

Through the above process, the participants are able to collaborate to recover the original secret quantum state \({|{s}\rangle }=\alpha {|{0}\rangle }+\beta {|{1}\rangle }\).

Security analysis

In the realm of quantum cryptography, the integrity of quantum secret sharing protocols is of paramount importance. Within this section, the robustness of the proposed scheme against five kinds of quantum attacks is meticulously scrutinized. These attacks include the man-in-the-middle attack, intercept-and-resend attack, entangle-and-measure attack, participant attack, and collective attack.

Man-in-the-middle attack. Within the scope of our security framework, we consider the presence of the man-in-the-middle attack. Alice and each participant use face-to-face methods or quantum secure direct communication to transmit personal identification numbers, so that the security of QSDC guarantees that PINs are safe in the process of information transmission.

Furthermore, it is analyzed that when participant \(P_j\) uses the corresponding operation to obtain a particle sequence and returns it back to Alice, this sequence is intercepted by Eve, who attempts to extract the participant’s PIN without being detected. Since Eve does not know the relevant information about \(\hbox {PIN}_j\) and \(\hbox {PIN}_{p_j}\), she has to prepare these authentication states randomly. Hence, she may randomly pick particles to try to evade authentication, but the probability of her making a correct pick is less than \(\frac{1}{2}\). Then the probability of Eve successfully passing the authentication process is quantified as

where l denotes the length of the authentication sequence. Thus, for l large enough, it can be considered that \(\text {P}_{pass}\approx 0\). Therefore, it can be considered that Eve cannot pass the identity authentication, and the authentication part can ensure its security.

Intercept-and-resend attack. To begin with, we delve into the specifics of the intercept-and-resend attack, a strategy wherein an eavesdropper may try to intercept the quantum states during the transmission, measure them, and then resend his own fake quantum state to a legitimate participant. In the particle distribution, these quantum shares are mainly inserted into the detected photon sequences, and the decoy photon technique is employed to check for eavesdropper’s attacks. For this purpose, some sample checking single photons are selected from the X-basis and Z-basis.

In the context of quantum communication, the scenario where an external eavesdropper, denoted as Eve, employs the intercept-and-resend attack poses a significant challenge to the security of quantum protocols. In this particular attack, Eve has the capability to intercept all transmitted quantum sequences during the communication process. She then proceeds to measure these quantum particles using either the X-basis or the Z-basis.

After conducting her measurements, Eve crafts and sends fabricated sequences of quantum particles to the legitimate communicating parties. However, a crucial aspect of this attack is that Eve lacks prior knowledge of the specific positions and measurement bases of the decoy particles embedded within the transmission. Decoy particles are strategically interspersed to detect any eavesdropping activities due to their unpredictable nature.

The presence of these decoy particles is pivotal as it compels Eve to introduce a significant number of errors during her interception attempt. The inherent probabilistic nature of quantum measurements in unknown bases means that Eve’s measurements will often result in incorrect outcomes, thereby revealing her eavesdropping efforts. This increased error rate serves as a detectable anomaly, alerting the legitimate parties to the presence of an eavesdropper and allowing them to subsequently abort the communication session to safeguard the information being exchanged.

If the eavesdropper successfully finds the right particle of the quantum state \({|{\Psi _s}\rangle }\) encoded the secret information in every sequence \(S_k\ (k=1,2,\cdots ,r,r+2,\cdots ,n)\), the successful probability is

where N represents the number of decoy particles in the sequence \(S_k\). Since each sequence is independent of each other sequences, the total successful probability for n sequences is

Thus, when the quantum state of the selected encoded information is certain and N gradually increases, then we have that

So this intercept-and-resend attack does not work in our scheme.

Entangle-and-measure attack. In the pursuit of acquiring sensitive information transmitted through quantum channels, an eavesdropper Eve employs sophisticated quantum strategies to compromise the security of the communication. One such method involves the preparation of an auxiliary quantum system and the application of a unitary transformation \(U_E\) to achieve entanglement between her auxiliary system and the quantum particles disseminated by the distributor.

For the basis \(Z=\{{|{0}\rangle },{|{1}\rangle }\},\) the above process is as follows,

where \(|E\rangle\) is the initial state of Eve’s ancillary system; \(|e_{kl}\rangle \ (k,l=0, 1)\) is the pure auxiliary state determined uniquely by the unitary transform \(U_E\), and \(|a_{00}|^2+|a_{01}|^2=1, |a_{10}|^2+|a_{11}|^2=1.\)

In order to circumvent the inadvertent increase in error rates associated with the entangled states, the eavesdropper Eve has to meticulously adjust her strategy to nullify the impact on the legitimate quantum communication. To this end, she is compelled to set the partial coefficients to zero for the entangled states, specifically, by enforcing \(a_{01}=a_{10}=0\). Therefore, Eq. (20) can be simplified as follows:

According to Eq. (21), Eve uses the unitary transform \(U_E\) acting in the initial state of the ancillary system \(|E\rangle\) with the basis \(X=\{{|{+}\rangle },{|{-}\rangle }\}\), which can be obtained

Similarly, to avoid introducing errors, Eve also needs to set the partial coefficients in Eq. (22) to zero, that is,

Without loss of generality, Eve uses the unitary operation \(U_E\) on the first particle of \({|{\Psi _s}\rangle }\) in Eq. (6) to obtain some useful information about this secret. In addition, by Eq. (23), we can have that

Upon employing the entanglement-and-measure attack, Eve may establish a quantum link with the transmitted particles using her auxiliary system. However, due to the inherent unpredictability and the principles of quantum mechanics that govern the legitimate users’ communication, Eve’s attack ultimately proves to be ineffective. Regardless of the changes in the transmitted particles, the information that Eve is able to glean from her auxiliary system remains constant and does not provide her with access to the valuable secret information being communicated. So the entangle-and-measure attack is unsuccessful.

Participant attack. In the QSS schemes, the issue of a participant attack assumes significant importance due to its relative ease of execution compared to external attacks. This type of attack poses a unique challenge as the participants within the protocol, by virtue of their direct involvement, have the potential to gain access to a greater depth of useful information than an external eavesdropper, who is typically restricted to intercepting transmitted quantum states. In this attack, we mainly consider the following three cases.

Case 1: Suppose that there exists a dishonest participant \(P_i\) in our scheme.

For this case, a dishonest participant can intercept other participants’ particles and resend the forged sequence, or entangle the ancillary system on the transmitted particles. However, these particles in our scheme are protected by the decoy photons from X-basis or Z-basis. From the above analysis of “intercept-and-resend attack” and “entangle-and-measure attack”, we can know that the dishonest participant cannot steal secret information from the transmitted particles due to these decoy particles.

On the other hand, if \(P_i\) is dishonest, he calculates the partial trace of \({|{\Psi _{s}}\rangle }{\langle {\Psi _{s}}|}\), i.e.,

In this situation, when the state \(\rho _{i}\) associated with a particular participant is identified as a maximal mixed state, this revelation points to the unsuccessful attempt by the dishonest participant to gain an advantage through illicit means.

Case 2: Suppose that there are more than one dishonest participant in the same group.

In the interest of preserving the symmetry of quantum states, we consider that all untrustworthy players belong to the third group \(\bar{G}_3=\{P_{3},\cdots ,P_{r}\}\). Similar analyses can be conducted for other scenarios accordingly. Assuming that these participants could choose the following two ways to recover the secret:

-

(1)

In the group \(\bar{G}_3\), all the participants directly measure the particles in their hands;

-

(2)

Participants use some controlled-NOT gates.

For (1), these participants, \(P_3,P_4,\cdots ,P_{r}\), carry out several measurements on their particles under the basis of \(\{|0\rangle ,|1\rangle \}\). At the same time, these participant \(P_3\) can get the following collapse states on his own particle.

If the measurement by \(P_3,P_4,\cdots ,P_{r}\) is \(|0\cdots 0\rangle\), then the quantum state \({|{\Psi _s}\rangle }\) can collapse to \({|{\Psi ^{0\cdots 0}_s}\rangle }\), where \({|{\Psi ^{0\cdots 0}_s}\rangle }\) is denoted by

If the measurement by \(P_3,P_4,\cdots ,P_{r}\) is \(|1\cdots 1\rangle\), then the quantum state \({|{\Psi _s}\rangle }\) can collapse to \({|{\Psi ^{1\cdots 1}_s}\rangle }\), where \({|{\Psi ^{1\cdots 1}_s}\rangle }\) is denoted by

Through Eqs. (25) and (26), it is not difficult to find that the particles in \(\bar{G}_3\) and other particles become product states, so that all the participants in \(\bar{G}_3\) cannot obtain any information.

For (2), suppose these participants use some controlled-NOT gates, where the particle of \(P_3\) are the control bits and the other remaining particles are the target bits. Therefore, the state \({|{\Psi _s}\rangle }\) is changed to

Therefore, \(P_{3}\) is in an entangled state in Eq. (27). If \(P_{3}\) wants to obtain the secret, he will take various methods to destroy the entanglement. However, it is hard to make the entangled state become a separable state since the other particles are always entangled with \(P_{3}\) in Eq. (27). If he cannot get that \({|{s}\rangle }=\alpha {|{0}\rangle }+\beta {|{1}\rangle }\), it means that he cannot have any information about the secret. Through the above analysis, it is shown that this scheme is safe.

Case 3: Suppose that there are more than one dishonest participant in the different group.

Due to the same status of each participant in \(\bar{G}_3\) and \(\bar{G}_4\), we consider only one participant in each group as a dishonest participant. The participants in the authorized set implemented in our protocol are from different groups, so each authorized set contains four participants. In turn, we focus on the case of subsets of the authorized sets. We take the authorized set \(\{P_1P_2P_3P_{r+2}\}\) as an example. Therefore, these sets \(\{P_1P_2P_3\},\{P_1P_2P_{r+2}\},\{P_1P_3P_{r+2}\},\{P_2P_3P_{r+2}\}\) are unauthorized.

For three unauthorized sets \(\{P_1P_2P_3\}\) and \(\{P_1P_2P_{r+2}\}\), we only analyze \(\{P_1P_2P_{3}\}\). The other one can be similar to the analysis.

If \(P_3\) measures the quantum state \({|{\Psi _s}\rangle }\) with a computational basis \(\{{|{0}\rangle },{|{1}\rangle }\}\), then the quantum state \({|{\Psi _s}\rangle }\) can collapse to \({|{\Psi ^{0}_s}\rangle }\) or \({|{\Psi ^{1}_s}\rangle }\) in Eqs. (11) and (12). Furthermore, \(P_1\) and \(P_{2}\) use the controlled-NOT gate in these quantum states \({|{\Psi ^{0}_s}\rangle }\) or \({|{\Psi ^{1}_s}\rangle }\). For convenience, we take \({|{\Psi ^{0}_s}\rangle }\) an example, that is,

Then, \(P_2\) measures the quantum state \({|{\tilde{\Psi }^0_s}\rangle }\) with a computational basis \(\{{|{0}\rangle },{|{1}\rangle }\}\), then the quantum state \({|{\tilde{\Psi }^0_s}\rangle }\) can collapse to

At this point, the particle of participant \(P_1\) is entangled with all the particles in group \(\bar{G}_4\), so that \(P_1\) can not remove the entanglement. Therefore, the set \(\{P_1P_2P_3\}\) can not obtain the original secret.

For two unauthorized sets \(\{P_1P_3P_{r+2}\}\) and \(\{P_2P_3P_{r+2}\}\), if \(P_3\) and \(P_{r+2}\) measure the quantum state \({|{\Psi _s}\rangle }\) with a computational basis \(\{{|{0}\rangle },{|{1}\rangle }\}\), then the quantum state \({|{\Psi _s}\rangle }\) can collapse to \({|{\Psi ^{00}_s}\rangle },{|{\Psi ^{01}_s}\rangle },{|{\Psi ^{10}_s}\rangle },{|{\Psi ^{11}_s}\rangle },\) where these states are in Eqs. (13) and (14).

It is easy that the particle of \(P_{1}\) is always entangled with \(P_{2}\). If the entanglement in Eqs. (13) and (14) cannot be destroyed here. Therefore these dishonest participants cannot obtain the original secret.

Collective attack. Under collective attack, Eve attempts to perform the operation on her ancillary state and the encoded quantum state, then she can extract the valuable information by measuring the ancillary state at any time. Assuming collective attacks, it was shown in Ref.34 that the key rate is:

where the infimum is over all collective attacks which induce the observed statistics. The computation of H(A|B) is trivial given values \(p_{i,j}\) for \(i, j \in \{0, 1\}\).

For the sake of calculation, the quantum states in Eq. (3) are analyzed here, and it is denoted by

Since the first participant in the authorized sets for recovery is relatively important, it is assumed here that Eve only attacks the first particle in Eq. (29). Furthermore, Eve implements a unitary operation \(V_E\) on the quantum state and her ancillary state \(|0\rangle _E\). Therefore, the following equations can be calculated

where \(|0\rangle _E\) is the initial state of Eve’s ancillary system; \(|e_{kl}\rangle \ (k,l=0, 1)\) is the pure auxiliary state determined uniquely by the unitary transform \(V_E\). According to the characteristics of unitary transformation, the above equations satisfy the conditions that

Therefore, the following state will be obtained after Eve implements the operation \(V_E\),

Furthermore, these four participants \(P_1,P_2,P_3,P_5\) who hold the particles in \(A_1\), \(A_2\), \(A_3\) and \(A_5\) then restore the original secret according to the previous scheme. The participants \(P_3\) and \(P_5\) measure their particles in the hand with computational base \(\{{|{0}\rangle },{|{1}\rangle }\}\). Then the participant \(P_1\) cooperates with \(P_2\) using a controlled-NOT gate, where the particles in \(P_1\)’s hand serve as control bits and the particles in \(P_2\) as target bits. After that, \(P_2\) measures his particles with computational base \(\{{|{0}\rangle },{|{1}\rangle }\}\). Based on the measurements by \(P_3,P_{5}\), \(P_1\) performs the appropriate operation. At this time, the mixed system of \(P_1\)-\(P_2\)-\(P_3\)-\(P_4\)-\(P_5\)-Eve can be described as

where

The following system can be obtained by tracing out \(P_2,P_3,P_4,P_5\) systems from the density matrix \(\rho _{A_3A_5A_2A_1A_4E}\):

Then the state \(\rho _E\) is denoted by

Therefore, the key rate is denoted by

Since participants \(P_2\), \(P_3\) and \(P_5\) return the measurement results to \(P_1\), \(P_1\) must get the original secret. Hence, \(H(A_1|A_3A_5A_2)=0\) holds. The challenge is to compute \(S(A_1|E)=S(\rho _{A_1E})-S(\rho _{E})\).

Next, we consider two types of channels: bit-flip channel and amplitude damping channel.

-

(1)

Bit-flip channel. For this channel, suppose that \({|{e_{00}}\rangle }={|{e_{10}}\rangle }=\sqrt{ap}{|{0}\rangle }\) and \({|{e_{01}}\rangle }={|{e_{11}}\rangle }=\sqrt{1-ap}{|{0}\rangle }\), where p is the noise coefficient and a is the strength of the bit flip channel. To simplify the calculation, let \(\alpha \beta ^*+\alpha ^*\beta =1\). In this case (see Fig. 7a):

-

If \(a=0.60\), we see that \(r > 0.1\) for all \(q \le 0.52\).

-

If \(a=0.80\), then \(r > 0.1\) for all \(q \le 0.39\).

-

If \(a=1.00\), then \(r > 0.1\) for all \(q \le 0.31\).

-

-

(2)

Amplitude damping channel. The channel is a type of noise channel model in quantum information that describes the process of energy dissipation. It simulates the interaction between a quantum system and its external environment, where energy is transferred from a higher energy level to a lower energy level. Assume the system is a qubit, and the environment is initially in the ground state \({|{0}\rangle }_E\). The amplitude damping channel can be realized through the unitary evolution \(U_{SE}\) of system and environment, where

$$\begin{aligned} U_{SE}{|{0}\rangle }_S{|{0}\rangle }_E= & {|{0}\rangle }_S{|{0}\rangle }_E, \\ U_{SE}{|{1}\rangle }_S{|{0}\rangle }_E= & \sqrt{1-ap}{|{1}\rangle }_S{|{0}\rangle }_E+\sqrt{ap}{|{0}\rangle }_S{|{1}\rangle }_E, \end{aligned}$$where p is the noise coefficient and a is the strength of the damping. Therefore, we take \({|{e_{00}}\rangle }={|{0}\rangle }\),\({|{e_{01}}\rangle }=\vec {0}\), \({|{e_{01}}\rangle }=\sqrt{1-ap}{|{0}\rangle }\) and \({|{e_{11}}\rangle }=\sqrt{ap}{|{1}\rangle }\). To simplify the calculation, let \(\alpha \beta ^*+\alpha ^*\beta =1\). In this case (see Fig. 7b):

-

If \(a=1.00\), we see that \(r > 0.1\) for all \(q \le 0.94\).

-

If \(a=1.25\), then \(r > 0.1\) for all \(q \le 0.76\).

-

If \(a=1.50\), then \(r > 0.1\) for all \(q \le 0.63\).

-

Our results clearly show that one of the important factors to this QSS protocol’s key rate, is the noise in the quantum channel. This makes sense, as any noise does not directly lead to an error in the process of restoring secrecy, thus, does not lead to additional information leaking. Therefore, the scheme is capable of withstanding a collective attack.

Comparison

In this section, we compare the proposed scheme with these schemes26,27,33,43,45,46 in Table 5. For the comparison of these schemes, an analysis is primarily conducted from six aspects: quantum resources, the type of shared secrets, measurement basis in these schemes, the realized access structure, and identity authentication.

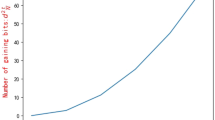

The common point of these protocols is that the use of quantum entanglement resources as the carrier of secret sharing, but only our proposed scheme and Li’s scheme33 use the 2-dimensional entangled state, and the remaining schemes26,27,43,45,46 use the d-dimensional entangled state as the carrier. For the construction of d-dimensional multipartite quantum entangled states, the methods use the quantum Fourier transform to turn \({|{0}\rangle }\) into a quantum superposition state \(\frac{1}{\sqrt{d}}\sum _{k=0}^{d-1}e^{2\pi \text {i}jk/d}{|{k}\rangle }\), and then the corresponding high-dimensional controlled gates are used. Realizing the quantum Fourier transform (QFT) in n-body systems requires \(\frac{n(n+1)}{2}\) quantum gates47. In our scheme, we need only \(2n+3-r_2\) gates to realize an n-body quantum entangled state. When \(r_2\ge 4\), the number of gates used in our scheme is significantly less than that the Fourier case (see Fig. 8). When controlled unitary gates are added, the preparation of d-dimensional quantum states will require more quantum gates. Therefore, the preparation of entangled states in d-dimension is more difficult than that in 2-dimension.

In addition, only our scheme and Bai’s scheme43 only use the computational basis for measurement, while the other schemes should have a joint measurement basis for many particles. This will increase the cost of the scheme.

In Refs.26,27,43,45, these schemes have no function of identity authentication for each participant. In our scheme and these schemes33,46, they add the function of participant identity authentication. The identity authentication of participants can further improve the security of the protocol, while excluding illegal participants from conducting protocol attacks. However, Li’s scheme33 can only realize the sharing of classical bits. Our scheme and Han’s scheme46 can realize the sharing of unknown quantum states, but in our scheme only the computational basis is used for measurement, while in Han’s scheme it applies the Bell basis measurement. Since the Bell basis is a joint measurement of two particles, the protocol is more complex and costs more quantum resources. In Refs.26,27,45,46, they implement the (n, n) threshold and (t, n) threshold structure, respectively. Our scheme achieves a more general access structure, which is more meaningful than the previous threshold scheme.

In summary, our proposed scheme is more economical in the use of quantum entanglement resources and more convenient to use only the computational basis during the implementation of the scheme. Furthermore, we can also achieve a more general access structure, and the identity authentication of participants is more secure in our scheme.

Conclusions

In this paper, a pair of quantum states were constructed through orthogonal arrays. Furthermore, a masker was provided such that the quantum state was masked into multipartite quantum systems. According to the masking of quantum states, we proposed the authenticable quantum secret sharing scheme and realized a class of special access structures. In the distribution phase, we shared an unknown quantum state \({|{s}\rangle }\) and masked the secret state into an n-party quantum systems. Then, each particle can be transmitted by the method of decoy photon states. In the reconstruction phase, participants in the authorized set used some measurements and a series of appropriate unitary operations on their particles to obtain the original information state. Moreover, we showed that our protocol was secure against man-in-the-middle attack, intercept-and-resend attack, entangle-and-measure attack and dishonest participant attack. At last, we compared it with existing quantum secret sharing schemes.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Shamir, A. How to share a secret. Commun. ACM 22(11), 612 (1979).

Blakley G R. Safeguarding cryptograhic keys. in Proceedings of the National Computer Conference (AFIPS, 1979), 313–317 (1979).

Hillery, M., Buzek, V. & Berthiaume, A. Quantum secret sharing. Phys. Rev. A 59, 1829 (1999).

Cleve, R., Gottesman, D. & Lo, H. K. How to share a quantum secret. Phys. Rev. Lett. 83, 648 (1999).

Gottesman, D. Theory of quantum secret sharing. Phys. Rev. A 61, 042311 (2000).

Deng, F. G., Zhou, H. Y. & Long, G. L. Circular quantum secret sharing. J. Phys. A: Math. Gen. 39, 14089–14099 (2006).

Xiao, L., Long, G. L., Deng, F. G. & Pan, J. W. Efficient multiparty quantum-secret-sharing schemes. Phys. Rev. A 69, 052307 (2004).

Gao, Z. K., Li, T. & Li, Z. H. Deterministic measurement-device-independent quantum secret sharing. Sci. China Phys. Mech. Astronomy 63(12), 1–8 (2020).

Singh, P. & Chakrabarty, I. Controlled state reconstruction and quantum secret sharing. Phys. Rev. A 109(3), 032406 (2024).

Moreno, M., Brito, S., Nery, R. V. & Chaves, R. Device-independent secret sharing and a stronger form of Bell nonlocality. Phys. Rev. A 101, 052339 (2021).

Roy, S. & Mukhopadhyay, S. Device-independent quantum secret sharing in arbitrary even dimensions. Phys. Rev. A 100, 012319 (2019).

Rathi, D. & Kumar, S. Verifiable dynamic quantum secret sharing based on generalized Hadamard gate. Quantum Inf. Process. 23(10), 328 (2024).

Li, C. L. et al. Breaking the rate-distance limitation of measurement-device-independent quantum secret sharing. Phys. Rev. Res. 5(3), 033077 (2023).

Qin, Y. et al. Efficient and secure quantum secret sharing for eight users. Phys. Rev. Res. 6(3), 033036 (2024).

Grice, W. P. & Qi, B. Quantum secret sharing using weak coherent states. Phys. Rev. A 100, 022339 (2019).

Senthoor, K. & Sarvepalli, P. K. Theory of communication efficient quantum secret sharing. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 68(5), 3164–3186 (2022).

Li, F. et al. A rational hierarchical (t, n)-threshold quantum secret sharing scheme. Quantum Inf. Process. 23(2), 60 (2024).

Gu, J. et al. Secure quantum secret sharing without signal disturbance monitoring. Opt. Express 29(20), 32244–32255 (2021).

Lai, H., Pieprzyk, J. & Pan, L. Dynamic hierarchical quantum secret sharing based on the multiscale entanglement renormalization ansatz. Phys. Rev. A 106(5), 052403 (2022).

Li, L. & Li, Z. The quantum secret sharing schemes based on hyperstar access structures. Inf. Sci. 664, 120202 (2024).

Cai, X. Q., Li, S., Liu, Z. F. & Wang, T. Y. Improving security of efficient multiparty quantum secret sharing based on a novel structure and single qubits. Sci. Rep. 14, 18385 (2024).

Cai, X. Q., Li, S., Liu, Z. F., et al. Measurement-device-independent quantum secret sharing. Adv. Quant. Technol. 2400060 (2016)

Tian, Y. et al. Dynamic multi-party to multi-party quantum secret sharing based on Bell states. Adv. Quant. Technol. 7(7), 2400116 (2024).

Peng, R. et al. Decentralized continuous-variable quantum secret sharing. Quantum Inf. Process. 22(10), 368 (2023).

Shen, A. et al. Experimental quantum secret sharing based on phase encoding of coherent states. Sci. China Phys. Mech. Astronomy 66(6), 260311 (2023).

Mansour, M. & Dahbi, Z. Quantum secret sharing protocol using maximally entangled multi-qudit states. Int. J. Theor. Phys. 59, 3876–3887 (2020).

Zhang, K. et al. A new \(n\)-party quantum secret sharing model based on multiparty entangled states. Quantum Inf. Process. 18, 1–15 (2019).

Bai, C. M., Zhang, S. & Liu, L. Verifiable quantum secret sharing scheme using d-dimensional GHZ state. Int. J. Theor. Phys., 1–13 (2021)

Rahaman, R. & Parker, M. G. Quantum scheme for secret sharing based on local distinguishability. Phys. Rev. A 91, 022330 (2015).

Bai, C. M., Zhang, S. & Liu, L. Quantum secret sharing for a class of special hypergraph access structures. Quantum Inf. Process. 21(3), 1–17 (2022).

Houshmand, M., Hassanpour, S. & Haghparast, M. An efficient controlled semi-quantum secret sharing protocol with entangled state. Opt. Quant. Electron. 56(5), 759 (2024).

Li, F. et al. Efficient and verifiable general quantum secret sharing based on special entangled state. IEEE Internet Things J. 11(8), 14127–14135 (2023).

Li, L. et al. Authenticable dynamic quantum multi-secret sharing based on the Chinese remainder theorem. Quantum Inf. Process. 23(2), 46 (2024).

Renner, R., Gisin, N. & Kraus, B. Information-theoretic security proof for quantum-key-distribution protocols. Phys. Rev. A 72(1), 012332 (2005).

Modi, K. et al. Masking quantum information is impossible. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120(23), 230501 (2018).

Liang, X. B. et al. Impossibility of masking a set of quantum states of nonzero measure. Phys. Rev. A 101(4), 042321 (2020).

Shang, W. M. et al. Quantum information masking of an arbitrary unknown state can be realized in the multipartite lower-dimensional systems. Phys. Scr. 98(3), 035102 (2023).

Li, M. S. & Wang, Y. L. Masking quantum information in multipartite scenario. Phys. Rev. A 98(6), 062306 (2018).

Ding, F. & Hu, X. Masking quantum information on hyperdisks. Phys. Rev. A 102(4), 042404 (2020).

Shen, Y. et al. Masking quantum information in the Kitaev Abelian anyons. Phys. A 612, 128495 (2023).

Wang, M. Y. et al. Masking quantum information in multipartite systems based on generator matrices. Laser Phys. 34(5), 055203 (2024).

Bai, C. M. et al. Masking quantum information in multipartite systems via Fourier and Hadamard matrices. Commun. Theor. Phys. 77(2), 025107 (2024).

Bai, C. M., Zhang, S. & Liu, L. Quantum secret sharing based on quantum information masking. Quantum Inf. Process. 21(11), 377 (2022).

Rao, C. R. Hypercubes of strength’d’leading to confounded designs in factorial experiments. Bull. Calcutta Math. Soc. 38, 67–78 (1946).

Rathi, D. & Kumar, S. A d-level quantum secret sharing scheme with cheat-detection \((t, m)\) threshold. Quantum Inf. Process. 22(5), 183 (2023).

Li, L., Han, Z. & Guan, F. Authenticable quantum multi-secret sharing scheme based on monotone span program. Quantum Inf. Process. 22(9), 342 (2023).

Nielsen, M. A. & Chuang, I. L. Quantum Computation and Quantum Information (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2010).

Acknowledgements

We want to express our gratitude to anonymous referees for their valuable and constructive comments. This work was funded by Science Research Project of Hebei Education Department under Grant No.BJ2025061 and the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant No.12301590.

Funding

This work was funded by Science Research Project of Hebei Education Department under Grant No.BJ2025061 and the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant No.12301590.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.M. Bai proposed the initial idea for this paper and wrote the initial draft of the manuscript, Y. X Shu calculated the relevant secure analysis and drawn some figures and S. Zhang participated in the discussion and revision of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bai, CM., Shu, YX. & Zhang, S. Authenticable quantum secret sharing based on special entangled state. Sci Rep 15, 10819 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-95608-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-95608-4

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Authenticable dynamic quantum secret sharing with hierarchical access structure

Quantum Information Processing (2025)