Abstract

In this study, we examine and analyze the solution for the pediculosis disease model utilizing the predictor–corrector approach in relation to the Caputo fractional derivative. The existence and uniqueness of the selected model have been examined. Furthermore, the existence of the equilibrium point and local asymptotic stability are inferred. For various orders of the given derivative, the numerical simulations are displayed. We use graphs to verify the obtained results. According to our main outcomes, finding lice infestations early is important for getting rid of them quickly and effectively and lowering the risk of getting them again. These findings were used to test how well treatments for head lice infestations work. In the context of human disease, the results of this research highlight the relevance of projected derivative and method in the analysis and behavior of diverse mathematical models that are defined by differential equations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Derivatives and integrals having arbitrary order will be referred to as fractional calculus (FC). After developing the integer-order derivatives, Leibniz invented non-integer derivatives. Many eminent researchers worked together to develop the mathematical foundation for arbitrary order derivatives1,2,3,4,5. FC has been found to be superior to classical calculus for behavior-related real-world problems and to provide a coherent and effective exposition of nature’s reality. Fractional differential equations (FDEs) provide a more precise and understandable solution to a problem than classical differential equations. Higher-order behaviors and complex non-linear systems can be better behaved by fractional order derivatives. The primary justification for taking fractional derivatives into account is because we are not limited to integer order and can take derivatives in any order. FC plays a vital role in capturing the memory and hereditary properties of complex systems. Its applications are widespread, with significant contributions to various branches of science and engineering. In recent years, FC has drawn a lot of attention in a number of disciplines, including electrodynamics6, signal processing7, fluid dynamics8,9, biomechanics10, financial modeling11,12, zoonotic disease13, optics14, chaos analysis15, magnetic properties16, human disease modeling17,18,19,20,21,22, neural networks23, and many others24,25,26,27,28,29. This growing interest in FC is a testament to its versatility and potential to provide new insights into complex phenomena.

Diseases such as malaria, HIV infection, dengue fever, influenza, Ebola virus, and cancer have been modeled using ordinary differential equations of integer order. However, in recent times, there has been a shift in focus towards modeling these diseases using fractional-order differential equations, which offer a more realistic and accurate representation of complex biological systems. So that FC describes the new features in the epidemiology of infectious diseases. In this study, we studied and considered the pediculosis disease (PD). A head lice infection is called pediculosis. Crawling insects called head lice reside in a person’s hair. The nits that the lice lay stick tightly to the hair shafts that are visible at the skin’s surface while sucking on the blood that is drawn from our scalp. Although head lice can afflict anybody, they most frequently impact families and children aged 3–11 years. Children are especially susceptible because they play together, making head-to-head contact with others and possibly sharing items that come into contact with their hair. Between 6 and 12 million people are reported to be affected by head lice infestations annually. The most typical head lice symptom is itching, especially in the areas closest to the ears, on the neck, and on the back of the head, where lice are more likely to live.

Castelletti and Barbarossa30 develop a mathematical model describing the population dynamics of lice in the head. Studying the life cycle of head lice is a more crucial step in treating infestations of lice. Using numerical simulations and computer experiments, they evaluate the efficacy of treatments for head lice infestations and also examine the potential approaches to treatment. Dagrosa and Elston31 describe that infection is not thought to be a disease transmission; it can cause significant distress, missed school days, and secondary diseases. Treatment with pyrethroids is advised, but resistance is frequent. Otti et al.32 developed a deterministic mathematical continuous time model that takes into account a fixed population size throughout the epidemic period in order to detect and eradicate non-life-threatening head lice. Birkemoe et al.33 worked with three datasets of Norwegian primary school students, ages six to twelve, which measured the prevalence of head lice: retrospective, point prevalence, and prospective methods. To evaluate the dynamics of the infestation, self-reported monthly incidences of head lice using a prospective approach were examined. Galassi et al.34 investigated the impact of confinement using an online survey on the lice prevalence during the COVID-19 lockdown in comparison to the pre-confinement condition. The number of insects that parents had recorded, the number of treatments, and the different control methods could all be distinguished thanks to the survey.

The intent of our study is to comprehend the PD (head lice) dynamics outbreaks with the help of the predictor–corrector (PC) method via fractional derivative of Caputo-type. The proposed framework has not yet been resolved using the specified PC approach. There are plenty of methods available to us for solving fractional models, but each has drawbacks such as assumptions, discretization, large simplifications, and others. But the proposed technique overcomes the limitations of other methods. Recent studies35,36,37,38 have demonstrated the effectiveness and versatility of this approach, which can be successfully apply to various models. Notably, this method simplifies complex problems, providing a more accurate and reliable tool for simulating fractional-order differential models.

This study aims to develop and analyze a fractional-order computational model for the dynamics of PD using the PC approach with the Caputo fractional derivative (CFD). The specific objectives include:

-

Construct a system of FDEs that characterizes the dynamics of pediculosis population transmission, infection, and recovery. Memory effects should be considered in order to compensate for the delayed effects of infection and treatment methods.

-

We establish the existence and uniqueness of solutions for the fractional-order model.

-

To comprehend how the disease will behave over the long run, identify the equilibrium points and evaluate their local asymptotic stability.

-

For the fractional-order model, we will use the PC approach to implement a numerical solution.

-

Examine the effects of various fractional orders on the dynamics of the infection. Evaluate how effective early identification and treatment methods are at managing pediculosis.

The present paper is structured as follows: Essential definitions and preliminary information are given in section “Preliminaries”. The preferred model formulation and description are explained in section “Model formulation”. Section “Existence and uniqueness analysis” delves into the uniqueness and existence of the model, providing a solid foundation for subsequent analysis. Building on this, section “Stability analysis investigates the stability of the model, ensuring its reliability and accuracy. The solution of the model is then presented in section “Model solution using PC scheme”, utilizing the PC method to provide a comprehensive numerical solution. A detailed discussion of the results is offered in section “Results and discussion”, where graphical representations of the findings are analyzed and their significance is highlighted. Finally, the paper concludes with a concise summary of the main contributions in section “Conclusion”.

Preliminaries

In this section, we provide an overview of key concepts and properties associated with fractional derivatives, laying the groundwork for further discussion.

Definition 1

According to Riemann–Liouville1, the fractional integral of order \(\kappa \geqslant 0\) for a function \(x(t) \in C_s(s \geqslant -1)\) is given as

Definition 2

The fractional derivative of a function \(x \in C_{ - 1}^s\) in Caputo1 sense is defined as

Linear property of CFD is

where \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\) are some constants.

Definition 3

Here is a description of the Mittag-Leffler function using a single operator1:

Model formulation

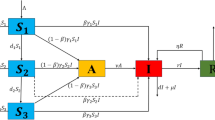

Here, the model of the disease pediculosis is defined. Many people ignore the PD because it cannot kill, although it can cause inconvenience and illness. Understanding the dynamics of disease transmission and awareness of the spread of the disease is essential. Otti et al.32 developed a mathematical model by considering the susceptible class, infected class, and recovered class to detect and eradicate non-life-threatening head lice. Based on this mathematical model, we formulated and extended it to five systems of ordinary differential equations describing the dynamics of pediculosis transmission. In the proposed model, \(S_A(t)\) indicates the susceptible population who are aware of pediculosis infection, \(S_N(t)\) denotes the susceptible population who are not aware of infection, \(I_S(t)\) symbolizes the infected population who can spread the disease to others, \(I_T(t)\) specifies the infected population who are under treatment, and R(t) represents the recovered population after treatment. Individuals who are aware of infection and not aware of infection enter the system through recruitment \((\Lambda _A,\Lambda _N)\) and transition between groups \((\rho , \eta )\). Infection spreads when \(S_N\) comes into contact with infected individuals \((I_S)\), with a transmission rate \(\sigma\). \(I_S\) can either progress to treatment \((\tau )\) or to be lost due to natural causes \((\mu )\). Treated individuals \((I_T)\) recover at rate \(\varepsilon\) or remain infected. Recovered individuals (R) may lose immunity and return to the susceptible class \((\varphi )\). Figure 1 visually represents these compartments and the transition rates among them. The schematic diagram uses directed arrows to indicate transitions between compartments. Each arrow is labeled with the corresponding transition rate.

The fractional-order approach improves accuracy by capturing long-term dependencies in infection dynamics, offering better predictions for public health strategies. This model helps understand lice transmission and evaluate treatment interventions in different population groups. Table 1 lists the parameters symbolized in the system previously discussed, together with their values, and the model under consideration can be expressed as follows in the CFD.

Given below are the initial conditions for the suggested model.

Existence and uniqueness analysis

In order to prove the uniqueness and existence, we rephrase model Eq. (5) as follows in a simple way for easy understanding:

\(S_A (0) = S_{A_0 }\), \(S_N (0) = S_{N_0 }\), \(I_S (0) = I_{S_0 }\), \(I_T (0) = I_{T_0 }\) and \(R (0) = R_0\) are the initial conditions. Here, \(^CD_t^\kappa\) represents the CFD of order \(\kappa\). We show that the fractional pediculosis model has a unique solution based on the results of fixed point theory. We show the analysis for \(S_A(t)\), and it will be similar for the other equations in the system Eq. (7). Consider

with the initial setting

where \(\textrm{X}_1:\left[ {0,\mathrm T} \right] \times {\Re }^n \times {\Re }^n \rightarrow {\Re }^n\) is continuous and \(S_A \in {\Re }^n,\,\,T > 0\).

Here, \({\Re }^n\) is the Euclidean space with n-dimensions that is defined using the norm \(\left\| . \right\|\).

Lemma 1

39 The function \(S_A \in C(\left[ {0,\mathrm T} \right] ;{\Re })\), which is a space of continuous function \(S_A:\left[ {0,\mathrm T} \right] \rightarrow {\Re }\) with a sub norm \(\left\| . \right\| _\infty\), is a solution to the above initial value problems Eqs. (8) and (9) on the interval \(\left[ {0,\mathrm T} \right]\), provided that it is a solution of the Volterra integral equation (VIE).

Theorem 4.1

(Existence theorem)26 Let \(\mathrm T^ * > 0\), \(P>0\), \(S_{A_0 } \in {\Re }\), and \(0 < \kappa \leqslant 1\). Assuming that the mapping \(\mathrm X_1:X \rightarrow \Re\) is continuous, we derive \(X: = \left\{ {\left( {t,S_A } \right) :t \in \left[ {0,\mathrm T^ * } \right] ,\,\,\left| {S_A - S_{A_0 } } \right| \leqslant P} \right\}\). \(Q: = \sup _{(t,S_A,S_N,I_S,I_T,R) \in G} \left| \mathrm{X_1 (t,S_A )} \right|\) is also defined and

The function \(S_A \in C\left[ {0,T} \right]\) may then be used to solve the initial value problems Eqs. (8) and (9).

Theorem 4.2

(Uniqueness theorem)26 Assume that \(P>0\), \(\mathrm T^*> 0\), and \(S_A (0) \in {\Re }\). Additionally, take into account \(0 < \kappa \leqslant 1\) and \(q = \lceil \kappa \rceil\). Let \(\textrm{X}_1:X \rightarrow {\Re }\) be a continuous mapping that satisfies the Lipschitz criteria for the second variable, that is followed as

for certain constants \(\lambda >0\), \(S_{A_1 }\), and \(S_{A_2 }\), are independent of t. Then, there is a unique solution \(S_A \in C\left[ {0,\mathrm T} \right]\) for the initial value problems Eqs. (8) and (9).

The well-posed fractional-order pediculosis disease model is ensured by the existence and uniqueness theorems, demonstrating the presence of a significant, stable, and credible solution. Because they verify that the model predictions are reliable and subject to arbitrary initial conditions, these theorems are essential in epidemiology. The study closely proves these features using fixed-point theorems. The model is a useful tool for comprehending and managing the spread of pediculosis because of its mathematical framework, which also increases its reliability.

Stability analysis

We can get the equilibrium points of the fractional PD model by setting the right-hand side of Eq. (5) to zero.

Solving Eq. (13), we obtain the equilibrium points such that

\(E^ * = (S_A ^ *,S_N ^ *,I_S ^ *,I_T ^ *,R^ * )\) is the disease-free equilibrium (DFE) point and

\(E^ {**} = (S_A ^ {**},S_N ^ {**},I_S ^ {**},I_T ^ {**},R^ {**} )\) is the endemic equilibrium (EE) point,

where

The average number of new disease infections based on the infection rate throughout time is the basic reproduction number (\(R_0\)). Only infected compartments are examined in order to calculate the value of \(R_0\). F and V stand for the transition rates and new infections of the compartments, respectively.

The Jacobian for the above matrix is evaluated at DFE point.

The non-negative matrix \(FV^{-1}\) is the next-generation matrix. Following that, we have

If \(R_0 < 1\), the DEF of Eq. (5) is locally stable; if \(R_0 > 1\), it is unstable. Biologically, the disease spreads if \(R_0 > 1\) and dies out if \(R_0 < 1\). Keeping \(R_0\) under control helps in the development of effective diseases prevention strategies. For the model under consideration, the Jacobian matrix J of Eq. (5) looks like this

The following matrix depicts the Jacobian matrix \(J^*\) at the DFE point:

The matrix \(J^*\) has the following eigenvalues:

\(\omega _1=-1.43361, \,\, \omega _2=-0.83478, \,\, \omega _3=-0.60578, \,\, \omega _4=-0.00701, \,\, \omega _5=-0.00578\).

By the results of the above eigenvalues, we can conclude that the considered system is stable because all the eigenvalues are negative.

The Jacobian matrix \(J^{**}\) at the point of EE is as follows:

The following are the eigenvalues that correspond to the matrix \(J^{**}\):

\(\gamma _1=-0.834798, \,\, \gamma _2=-0.607495, \,\, \gamma _3=0.0959542, \,\, \gamma _4=-0.0933043, \,\, \gamma _5=-0.00646954\).

The system under consideration is unstable at EE point because all the eigenvalues are not negative.

According to the stability analysis, it is asymptotically stable at disease-free equilibrium points, which means that regardless of the initial conditions, the infection will eventually vanish. This occurs because each infected individual transmits the infestation to fewer than one new person on average, leading to a natural decline in cases over time. From a biological perspective, this suggests that the lice can be eradicated with the treatment and hygiene, preventing long-term persistence and reducing the risk of future outbreaks.

Model solution using PC scheme

It is well known that using numerical methods to solve ordinary differential equations is not suitable for solving differential equations of any order. We now discuss the PC approach, which is a generalization of the classical trapezoidal rule. Numerous real-world applications have demonstrated the efficiency of this technique. Here, we employ the PC approach to determine the predicted model’s solution35.

Let us examine the fractional-order differential equation of the preferred model

Let us consider a uniform grid \(\left\{ {t_r = rh:\,r = \, - m,\,\, - m + 1,\, - m + 2,...,\, - 1,\,0,\,1,...\,\,\mathbb {N}} \right\}\) and \(\mathbb {N}h = T\), where \(\mathbb {N}\) is the set of natural numbers and m are integers.

Let us assume that the approximations have already been computed. \(S_{A_h } (t_i ) \approx S_A (t_i ),\,(i = - m,\, - m + 1,\, - m + 2...,\, - 1,\,0,\,1,...,\,r)\) and we wish to compute \(S_{A_h } (t_{r + 1} )\) using the VIE, which is equal to Eqs. (14) and (15).

For \(S_A (t_r )\) in Eq. (17), we make use of approximations \(S_{A_h } (t_r )\). Moreover, Eq. (17) uses the product trapezoidal quadrature formula to evaluate the integral. Therefore, the corrector formula is

where

The term \(S_{A_h } (t_{r + 1} )\) is unknown and appears on both sides of Eq. (18). Because of the nonlinearity of \(\textrm{X}_1\), it is not possible to solve Eq. (18) explicitly for \(S_{A_h } (t_{r + 1} )\). Therefore, we substitute an estimate \(S_{A_h } ^p (t_{r + 1} )\), known as the predictor, for the term \(S_{A_h } (t_{r + 1} )\) on the right-hand side. Eq. (18) evaluates the predictor term using the product rectangle rule.

where

Therefore, based on the calculations performed above, the corrector formulas for each system of Eq. (7) are

Likewise, the predictor terms are

Results and discussion

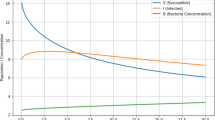

For the obtained PC method solutions Eqs. (22) and (23), we coded Mathematica to execute graphical simulations using the numerical values listed in Table 1. Figure 1 illustrates how individuals move between different infestation states, considering natural births, infections, treatments, recoveries and also provides a clear and structured visual representation of complex systems. This model helps in understanding the dynamics of lice infestations and devising effective control strategies. The kind of the outcomes obtained by the proposed solution approach for \(S_A(t)\) in relation to time t for various \(\kappa\) values and fixed value of other parameters is illustrated in Fig. 2. Similarly, the nature of \(S_N,\) \(I_S,\) \(I_T\) and R are outlined in Figs. 3, 4, 5 and 6.

In Fig. 2, we can see that how a susceptible individuals decreases over time. Figure 3 illustrates the decrease in the number of susceptible people who were unaware of infection because of the rate of change from unaware to aware of infection \(\eta .\) Figures 4 and 5 shows that while there are more infected individuals in the early stages, after a while there are zero because the infected people have switched to a treatment class, which also helps to stop the infection from spreading. Figure 6 describes the recovery individuals over time. Then, in order to offer the simulations more flexibility, we change the numerical values of some parameters \(\rho ,\) \(\theta\) and \(\varepsilon\) to examine the characteristics of the classes. So that, Figs. 7, 8 and 9 illustrates how the nature of the classes varies with regard to time. Infection levels are considerably decreased by increasing the treatment rate. Higher rates of recurrent infections make it more difficult to eliminate infections and emphasize the importance of comprehensive treatment to avoid reinfection.

Based on the practical observations provided, we have seen that the use of fractional derivatives helps us to more effectively model the structure of pediculosis infection. Compared to integer-order models, which have a tendency to overstate recovery rates, the fractional-order model offers more realistic infection trends. Fractional derivatives are a better tool for epidemiological forecasting because of the memory effect, which enables better simulation of delayed infection removal and reinfection risks. The findings emphasize how crucial early identification initiatives, hygiene education, and focused treatment are to successfully managing and preventing pediculosis outbreaks. Therefore, we provide future predictions about the proposed disease that are more accurate via fractional derivative.

Conclusion

In this study, a computational technique based on the PC approach has been hired to numerically solve the fractional-order PD. With the use of the CFD and preferred method, numerical solutions are obtained for the given model. The model offers a more accurate depiction of infection spread, recovery delays, and reinfection risks by incorporating memory effects. We have displayed different graphical outcomes with varying fractional order levels. The illustrations provided in this paper show how fractional derivative and parameter values both continuously impact the outcome. It is evident from numerical and stability analysis that the parameters of the fractional-order pediculosis model at a certain time are dependent upon it. Therefore, the parameter values have a critical role in deciding the proportion of individuals who recover from their illness. The behaviour of the solution is effectively illustrated by the proposed method, which is helpful in accurately predicting the pediculosis model. This algorithm ensures stability and precision in solving FDEs, making it a reliable tool for epidemiological modeling. We hope that researchers will explore and apply the proposed PC approach to solve a variety of nonlinear models, including fractional derivatives. Our findings demonstrate that early detection and treatment lead to the termination of the disease and also mitigate the risk of reinfection. Compared to integer-order models, the fractional approach better predicts real-world infection trends, providing deeper insights into disease control strategies. We aim to solve several more cutting-edge fractional models in the future and evaluate them against numerical techniques. The model offers valuable insights into controlling lice infections and underscores the utility of fractional calculus in epidemiology. Future research can extend the model to include environmental reservoirs, human behavior, and reinfection probabilities can enhance its applicability. Further, the efficacy of interventions may be increased by applying fractional optimal control theory to optimize control systems. In order to improve parameter estimations and provide practical reliability, validation using actual epidemiological data is essential. Stochastic fluctuations in infection dynamics can also be better understood by using stochastic fractional models. Finally, expanding the model to include resistance mechanisms or multi-host interactions will help us better understand how pediculosis disease spreads.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Change history

17 May 2025

The original online version of this Article was revised: In the original version of this Article the grant number in the Acknowledgements and Funding sections was incorrect. The correct grant number is “IMSIU-DDRSP2501”.

References

Podlubny, I. Fractional Differential Equations (Academic Press, New York, 1999).

Caputo, M. Elasticità e dissipazione Vol. 150 (Zanichelli, Bologna, 1969).

Miller, K. S. & Ross, B. An introduction to the fractional calculus and fractional differential equations. (1993).

Ross, B. The development of fractional calculus 1695–1900. Hist. Math. 4(1), 75–89 (1977).

Caputo, M. Linear Models of Dissipation whose Q is almost Frequency Independent-II. Geophys. J. Int. 13(5), 529–539 (1967).

Tarasov, V. E. Fractional vector calculus and fractional Maxwell’s equations. Ann. Phys. 323(11), 2756–2778 (2008).

Cruz-Duarte, J. M., Rosales-Garcia, J., Correa-Cely, C. R., Garcia-Perez, A. & Avina-Cervantes, J. G. A closed form expression for the Gaussian-based Caputo-Fabrizio fractional derivative for signal processing applications. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 61, 138–148 (2018).

Pavani, K., Raghavendar, K. & Aruna, K. Solitary wave solutions of the time fractional Benjamin Bona Mahony Burger equation. Sci. Rep. 14, 14596 (2024).

Faridi, W. A., Jhangeer, A., Riaz, M. B., Asjad, M. I. & Muhammad, T. The fractional soliton solutions of the dynamical system of equations for ion sound and Langmuir waves: A comparative analysis. Sci. Rep. 14, 30473 (2024).

Deebani, W., Jan, R., Shah, Z., Vrinceanu, N. & Racheriu, M. Modeling the transmission phenomena of water-borne disease with non-singular and non-local kernel. Comput. Methods Biomech. Biomed. Eng. 26(11), 1294–1307 (2023).

Sweilam, N. H., Abou Hasan, M. M. & Baleanu, D. New studies for general fractional financial models of awareness and trial advertising decisions. Chaos, Solitons Fractals 104, 772–784 (2017).

Jhangeer, A., Faridi, W. A. & Alshehri, M. Soliton wave profiles and dynamical analysis of fractional Ivancevic option pricing model. Sci. Rep. 14, 23804 (2024).

Peter, O. J. Transmission dynamics of fractional order brucellosis model using caputo–fabrizio operator. Int. J. Differ. Equ. 2020(1), 2791380 (2020).

Nisar, K. S., Jothimani, K. & Ravichandran, C. Optimal and total controllability approach of non-instantaneous Hilfer fractional derivative with integral boundary condition. PLoS ONE 19(2), e0297478 (2024).

Baleanu, D., Wu, G. & Zeng, S. Chaos analysis and asymptotic stability of generalized Caputo fractional differential equations. Chaos, Solitons Fractals 102, 99–105 (2017).

Luo, J. Traveling wave solution and qualitative behavior of fractional stochastic Kraenkel–Manna–Merle equation in ferromagnetic materials. Sci. Rep. 14, 12990 (2024).

Jan, R., Razak, N. N. A., Boulaaras, S., Rehman, Z. U. & Bahramand, S. Mathematical analysis of the transmission dynamics of viral infection with effective control policies via fractional derivative. Nonlinear Eng. 12(1), 20220342 (2023).

El-Mesady, A., Peter, O. J., Omame, A., & Oguntolu, F. A. Mathematical analysis of a novel fractional order vaccination model for Tuberculosis incorporating susceptible class with underlying ailment. Int. J. Model. Simul. 1–25 (2024).

Archana, D. K., Prakasha, D. G., Veeresha, P. & Nisar, K. S. An efficient technique for one-dimensional fractional diffusion equation model for cancer tumor. Comput. Model. Eng. Sci. 141(2), 1347–1363 (2024).

Alshehri, A., Shah, Z. & Jan, R. Mathematical study of the dynamics of lymphatic filariasis infection via fractional-calculus. Eur. Phys. J. Plus. 138(3), 1–15 (2023).

Peter, O. J., Fahrani, N. D. & Chukwu, C. W. A fractional derivative modeling study for measles infection with double dose vaccination. Healthc. Anal. 4, 100231 (2023).

Addai, E., Adeniji, A., Peter, O. J., Agbaje, J. O. & Oshinubi, K. Dynamics of age-structure smoking models with government intervention coverage under fractal-fractional order derivatives. Fractal Fract. 7(5), 370 (2023).

Ravichandran, C., Valliammal, N. & Nieto, J. J. New results on exact controllability of a class of fractional neutral integro-differential systems with state-dependent delay in Banach spaces. J. Frankl. Inst. 356(3), 1535–1565 (2019).

Jan, R., Boulaaras, S., Alnegga, M. & Abdullah, F. A. Fractional-calculus analysis of the dynamics of typhoid fever with the effect of vaccination and carriers. Int. J. Numer. Model. Electron. Netw. Devices Fields 37(2), 3184 (2024).

Yadav, P., Jahan, S., Shah, K., Peter, O. J. & Abdeljawad, T. Fractional-order modelling and analysis of diabetes mellitus: Utilizing the Atangana-Baleanu Caputo (ABC) operator. Alex. Eng. J. 81, 200–209 (2023).

Archana, D. K., Prakasha, D. G. & BinTurki, N. Modelling yeast prion dynamics: A fractional order approach with Predictor–Corrector algorithm. Fractal Fract. 8(9), 542 (2024).

Peter, O. J. et al. A mathematical model analysis of meningitis with treatment and vaccination in fractional derivatives. Int. J. Appl. Comput. Math. 8(3), 117 (2022).

Jan, R. et al. Fractional view analysis of the impact of vaccination on the dynamics of a viral infection. Alex. Eng. J. 102, 36–48 (2024).

Peter, O. J. et al. Fractional order mathematical model of monkeypox transmission dynamics. Phys. Scr. 97(8), 084005 (2022).

Castelletti, N. & Barbarossa, M. V. Deterministic approaches for head lice infestations and treatments. Infect. Dis. Model. 5, 386–404 (2020).

Dagrosa, A. T. & Elston, D. M. What’s eating you? head lice (Pediculus humanus capitis). Cutis 100(6), 389–392 (2017).

Otti, E. E., Okorie, E. C. & Bulus, S. M. Analysis and numerical simulation of deterministic mathematical model of pediculosis capitis. Int. J. Eng. Manuf. 13(1), 1–13 (2023).

Birkemoe, T. et al. Head lice predictors and infestation dynamics among primary school children in Norway. Fam. Pract. 33(1), 23–29 (2016).

Galassi, F. et al. Head lice were also affected by COVID-19: A decrease on Pediculosis infestation during lockdown in Buenos Aires. Parasitol. Res. 120(2), 443–450 (2021).

Kumar, P. & SuatErturk, V. A case study of Covid-19 epidemic in India via new generalised Caputo type fractional derivatives. Math. Methods Appl. Sci. 46(7), 7930–7943 (2023).

Alzaid, S. S., Kumar, A., Kumar, S. & Alkahtani, B. S. T. Chaotic behavior of financial dynamical system with generalized fractional operator. Fractals 31(04), 2340056 (2023).

Odibat, Z. A universal predictor-corrector algorithm for numerical simulation of generalized fractional differential equations. Nonlinear Dyn. 105(3), 2363–2374 (2021).

Veeresha, P. The efficient fractional order based approach to analyze chemical reaction associated with pattern formation. Chaos, Solitons Fractals 165, 112862 (2022).

Cong, N. D. & Tuan, H. T. Existence, uniqueness and exponential boundedness of global solutions to delay fractional differential equations. Mediterr. J. Math. 14(5), 193 (2017).

Acknowledgements

All the authors are thankful to the referees for their valuable suggestions in the improvement of the manuscript. Also, the authors extend their appreciation to Deanship of Scientific Research at Imam Mohammad Ibn Saud Islamic University (IMSIU) for funding this research work through grant number IMSIU-DDRSP2501.

Funding

This work was supported and funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research at Imam Mohammad Ibn Saud Islamic University (IMSIU) (grant number IMSIU-DDRSP2501).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Naveed Iqbal: Methodology, Writing-original draft, Visualization, Writing-review & editing. DK Archana: Software, Investigation, Methodology, Writing-original draft & Writing-review & editing. DG Prakasha: Supervision, Methodology, Writing-original draft, Writing-review & editing. Meraj Ali Khan: Visualization, Methodology, Writing-original draft, Writing-review & editing. Abdul Haseeb: Visualization, Validation, Writing-original draft, Writing-review & editing. Ibrahim Al-Dayel: Visualization, Writing-review & editing, Methodology. All authors have read and agreed to publish the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Iqbal, N., Archana, D.K., Prakasha, D.G. et al. Fractional-order computational modeling of pediculosis disease dynamics with predictor–corrector approach. Sci Rep 15, 11559 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-95634-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-95634-2