Abstract

Optimization of heat and mass transfer via higher thermally conductive generalized nonlinear materials namely, the Cross fluid is one of the major contributions of this work. This particular work is further analyzed effectively in the presence of linear reactions as well as solar radiation. The flow configuration is assumed with anticlockwise rotation which guarantees more heat transfer as compared to the linear or translator motion of such materials. Specifically, the generalized concept of Brownian motion as well as thermophoretic forces are utilized in the swirling motion of shear rate-dependent viscosity material which plays a significant role in science and industries. However, an enhancement in the conduction is caused by the non-uniform nanoparticle concentration and this is due to the involvement of the thermo diffusion phenomenon. Moreover, the probability of an extra degree of freedom to the heat equation is reduced by the introduction of the radiation which alternately provided a significant contribution to the thermal conductivity maximization. Additionally, the appearance of linear reaction in the concentration equation is a foundation that is based on the first-order apparent kinetics is one of the hydrolysis of the anticancer cisplatin drugs. Mathematical equations are developed and then solved by using one of the modified collocation methods. The time relaxation constant reduced the pressure and enhanced the rotational flow speed. The reduction in pedesis and radiation caused enhancement in the pressure and temperature. As the first-order reaction rate increases, the material concentration decreases, while radiation enhances the heat transfer rate. The Schmidt number effectively reduces the mass flow rate, whereas the reaction rate enhances it. The entire scheme is validated by providing a well-matched comparison.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Fluid motion due to spinning disk is a concept in fluid dynamics that refers to the flow of a liquid over a spinning disk. This configuration is commonly applied in various applications, such as centrifugal pumps, gas turbines, and other rotating machinery. Initially, the fluid flow due to spinning disk was discussed by Karman1. Turkyilmazoglu2 determined the solution of viscous liquid flow owing to spinning disk with additional effect in the form of magnetic field. Griffiths3 addressed the flow generalized liquid over a non-stationary disk. Mustafa4 demonstrated the importance of nano-liquid motion on a swirling disk with slip conditions. Lv et al.5 presented the bio-convective Reiner-Rivlin nano-fluid flow over a spinning disk, considering time-dependent flow heat flux and conducting an entropy generation analysis. Recently, Sharma et al.6 elucidated the impacts of Dufour as well as Soret during the flow of viscous liquid over a spinning disk. Ming et al.7 investigated the transfer of heat behavior of non-linear liquid on a spinning disk with a generalized thermal conductivity. Alkuhayli8 examined the heat transfer characteristics of hybrid nanofluid flow on a rotating disk, taking into account the behavior of thermal energy. Mahmud et al.9 investigated the heat transfer in inclined flow directed towards a revolving disk, considering the behavior of MHD. On the other hand, Kanwal et al.10 described the combined effects of heat-mass transport during nano-fluid flow, accounting for factors such as mixed convection (both linear and nonlinear), thermal radiation as well as activation energy, specifically over a spinning disk.

Nanofluid is a type of fluid that consists of a base fluid such as tiny suspended particles as well as ethylene glycol called nanoparticles. These nanoparticles typically have diameter size is (1–100 nm). The nanoparticles used in nano-fluids can be made of different materials, like as metals (such as copper, aluminum, or silver). The extension of small particles mean nano-size particle to the base liquid in nano-liquid can lead to a significant improvement in several properties of the liquid. In heat transfer and cooling process, the nano-fluids have guaranteed excellent thermal conductivity, which makes them suitable for enhancing heat transfer in various cooling systems. The concept of nano-fluids was first introduced by Choi11. Ramzan et al.12 examined the Von Karman spinning nanofluid flow, considering the modified law of Fourier as well as non-uniform properties in both liquid and gas conditions. Dharmaiah et al.13 explored the nuclear reactor application involving non-linear liquid flow with the Falkner-Skan term, including the effects of Brownian motion, thermophoresis as well as thermal emission past a wedge. The bioconvective hybrid flow using microorganism migration as well as Buongiorno’s model under convective conditions was published by Hussain et al.14 The Scrutiny of nonlinear nanoliquid flow under the effect of MHD with chemical reaction as well as slippery effects along cylindrical shape was reported by Bilal et al.15. Palencia et al.16 presented the ANFIS-PSO analysis of axisymmetric tetra-hybrid nano-fluid flow comprising Cu-CNT-Graphene-TiO2 with WEG-Blood, considering radiation as well as an inclined magnetic field. Lakshmi et al.17 examined the impact of Darcy–Forchheimer Fe3O4-CoFe2O4-H2O hybrid nano-fluid flow with MHD as well as viscous dissipation effects over a permeable stretching sheet. Afridi et al.18 presented a theoretical analysis of MHD non-linear 2-phase nano-fluid flow, considering the effects of viscous dissipation as well as chemical reactions. Continuing to work in the same area, many methods like Physics-informed neural networks (PINNs) are a powerful tool for solving higher non-linear equations in a data-driven manner as well as they have gained significant attention in fields such as non-materials science, engineering and so on. Specifically, in the context of designing high-energy storage performance polymer nano-composites, PINNs can be used to simulate the phase field evolution of these materials. Liu et al.19 investigated the use of physics-informed neural networks for phase-field simulations in the design of polymer nano-composites with high energy storage performance. The Halpin–Tsai model is an analytical model used to predict the effective properties of composite nano-materials, particularly those consisting of a polymer matrix as well as reinforcing nano-particles. Zhu et al.20 reported on predicting the properties of particle-reinforced composite materials through an enhanced Halpin–Tsai model.

Non-Newtonian fluids encompass a wide range of fluids whose flow behavior differs from the straightforward linear connection between shear stress as well as shear rate that defines Newtonian fluids. This category includes shear-thinning fluids, which decline in viscosity as shear rate escalates, shear-thickening liquids, which rise in viscosity under similar conditions, as well as Bingham plastics, which behave as solids until a yield stress is exceeded. Mebarek et al.21 examined the thermal as well as flow dynamics of MHD-Burgers’ fluid induced by a stretching cylinder, considering both internal heat generation as well as absorption. Aljedani et al.22 conducted a computational study on non-linear rheology for 3-D swirling plates, using the Yamada-Ota and Xue models. A generalized Newtonian fluid, on the other hand, is a subclass of non-Newtonian fluids characterized by a connection between shear stress as well as shear rate that can be described by a power law model. In these fluids, the viscosity is not constant but varies with shear rate, allowing for the modeling of shear-thinning or shear-thickening behaviors. In contrast, the Cross fluid flow model is a more specialized approach often used for fluids that exhibit both shear-thinning behavior and a yield stress, which is the minimum stress required to initiate flow. The first significant work on the Cross fluid model was done by Cross23. Cross introduced the model to describe the flow behavior of non-Newtonian fluids, particularly those that exhibit shear-thinning behavior with a yield stress. To analyze the flow behavior of Cross fluid, Hauswirth et al.24 conducted a study on the flow of Cross fluid through a porous system. The research conducted by Awais and Salahuddin25 focuses on the development of a radiative-MHD Cross liquid thermophysical model with the behavior of magnetic field.

The radiation in a fluid motion refers to the transfer of heat energy through electro-magnetic waves in the form of infrared radiation within a fluid medium, such as a gas or a liquid. This mode of heat transmission does not require any physical contact. Thermal radiation in fluid refers to the emission of electromagnetic waves by the fluid’s molecules due to their temperature, without the need for a medium for heat transfer. These charged particles emit electromagnetic waves as they oscillate and change energy levels. Thermal radiation plays a significant role in fluid dynamics and has various applications. In the last, in case of solar thermal power plants, for instance, use mirrors or lenses to concentrate sunlight onto a receiver, which then absorbs the thermal radiation and converts it into usable turbine to generate electricity. In this study, they explored the concept of double diffusion and magneto-nanoliquid with the convective prescribed boundary restrictions. Acharya26 investigated the effects of active as well as passive controls of nano-particles on radiative nano-fluidic transfer over a spinning disk. Shah et al.27 studied entropy optimization in a 4th -grade nano-liquid flow over a flexible Riga wall, considering the effects of thermal radiation as well as viscous dissipation. Mahmood et al.28 investigated the impact of thermal radiation on heat generation as well as viscous dissipation in an unsteady hybrid nano-fluid flow across a double-stratified sphere. Hussain et al.29 studied the flow of viscous nanofluid with radiation over a permeable, stretched swirling disk, considering the effect of generalized slip. Noreen et al.30 conducted a comparative study of ternary-hybrid nano-fluids, examining the role of radiation as well as Cattaneo-Christov heat flux between double spinning disks. Elboughdiri et al.31 presented a combined thermal performance analysis that includes dust particles, Hall and ion slip currents as well as tetra-hybrid nanoparticles on Howarth’s wavy pipe. Sohail et al.32 applied a finite element tool to analyze heat-mass transport in a water-based nano-fluid model, considering quadratic thermal radiation in a disk. In future perspective, the same concept can be utilized in heat transfer management. For instance the heat transfer through stretchable Stretchable as well as leak-proof liquid metal networks present a promising solution for thermal management, particularly in advanced, flexible, and high-performance electronic devices. By harnessing the unique properties of liquid metals such as their excellent thermal conductivity, flexibility, and low melting points which is combined with innovative encapsulation and structural designs, efficient and durable thermal management systems can be developed. Li et al.33 investigated stretchable as well sd leak-proof liquid metal networks for thermal management. The research on thermoacoustoelasticity for elastic wave propagation in preheated and prestressed solid rocks provides valuable insights into how thermal and mechanical factors influence wave behavior in geological materials. Yang et al.34 reported on thermoacoustoelasticity in elastic wave propagation within preheated and prestressed solid rocks.

Novelty of the work

The novelty of this research lies in its innovative approach to examining the Cross fluid flow over a rotating disk, incorporating the simultaneous effects of Brownian motion, thermophoretic forces, and thermal radiation. While existing studies have explored these individual phenomena, this work is unique in its integrated analysis of how these factors interact within a single system. By considering the behavior of radiation on heat transfer alongside the micro-scale influences of Brownian motion and thermophoresis on particle movement, this study provides a more comprehensive understanding of the flow dynamics and heat dissipation processes. Furthermore, the rotating disk geometry introduces a novel aspect, enabling an exploration of how rotational motion affects these coupled effects in both fluid and nanoparticle behavior. This research not only deepens the understanding of complex heat and mass transfer in nanofluid systems but also offers potential applications in enhancing the efficiency of cooling systems, energy devices, and nanotechnology-based processes.

Research gap

Cross-fluid rotational conduct is the first time characterized. Brownian motion and thermophoretic force and introduced in the rotation of Cross liquid. The heat as well as mass flows are significantly analyzed with the impact of solar radiation and linear 1st-order chemical reaction, respectively.

Limitations and research questions

The constraints and questions found during the literature study of the spinning flow of generalized nonlinear liquid materials served as a major foundation for the start of this effort. For low Reynolds number, the equations are mathematically modeled. Moreover, the higher viscosity boundary layer approximation theory is the sole way to explicitly formulate the flow equations. The applicability of the numerical tools is the basis for its selection. Additionally, only problems without singularity at the endpoints may be solved using the updated version of bvp4c. To facilitate comprehension of the study’s necessity, the primary research questions are: How does thermal radiation impact heat transfer characteristics in the system? What role does Brownian motion play in modifying flow dynamics and heat transfer in the Cross fluid flow? How do thermophoretic forces influence particle distribution and overall flow behavior? Additionally, how do the combined behavior of radiation, Brownian motion as well as thermophoresis alter the velocity and temperature profiles of the fluid? What influence does the rotation speed of the disk have on heat transfer and fluid flow under these combined effects? Furthermore, how do variations in fluid properties, such as thermal conductivity as well as viscosity, affect the interaction between thermal radiation, Brownian motion, and thermophoresis? Lastly, what are the combined effects of thermal radiation and Brownian motion on the heat and mass transfer rate in this system?

Problem description

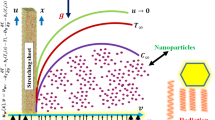

We consider a steady, 3-D flow as well as incompressible Cross fluid flow over a rotating disk, incorporating the effects of Brownian motion, thermophoresis, and thermal radiation and the disk is rotating counterclockwise around the z-axis at a constant angular velocity, denoted as Ω. The disk is located at z = 0 and has a radius \(\left( r \right)\). We use polar coordinates, where \(r\) represents the radial direction, φ is the tangential (or angular) direction, and \(z\) is the vertical direction. The flow has three velocity components: \(u\) in the radial direction \(\left( r \right)\), \(v\) in the tangential direction (φ), and \(w\) in the vertical direction \(\left( z \right)\).The fluid’s temperature, pressure, and concentration are represented by \(\left( {T, P,C} \right)\), respectively. At the surface of the rotating disk, we assume a uniform temperature \(\left( {T_{w} } \right)\) and a uniform concentration \(\left( {C_{w} } \right)\). Meanwhile, the ambient fluid surrounding the disk has a uniform temperature \(\left( {T_{\infty } } \right)\), pressure \(\left( {P_{\infty } } \right)\) as well as concentration \(\left( {C_{\infty } } \right)\). Additionally, thermal effects play a significant role in the flow behavior and the heat transfer process.

The assumptions for the problem

The rheological rotating nature of generalized non-linear material is affectively described with mathematical equations by making some assumptions as under:

-

Fig. 1 illustrates the horizontal placement of the revolving.

-

Cylindrical co-ordinates, i.e., \(\left( {r,\,\varphi ,\,z} \right)\) are applied.

-

\(\vec{V} = \left( {0,\,r\Omega ,\,0} \right)\) rotates the spinning apparatus.

-

Wall temperature as well as volume fraction and \(T_{w}\) as well as \(C_{w}\), respectively and the upstream temperature as well as volume fraction for the distance from the surface are \(T_{\infty }\)&\(C_{\infty }\), respectively.

The governing equations for the given problem namely continuity, momentum, temperature and concentration are illustrated as:

where, p is the pressure, Rc is chemical reaction co-efficient, \(\tau\) is the extra stress tensor, (DB, DT) stands for coefficient of Brownian motion and thermophoretic diffusion and qr is radiative heat flux and defined as \({\text{q}}_{{\text{r}}} = - \frac{4}{3}\frac{{\sigma^{*} }}{{k^{*} }}T_{\infty }^{3}\frac{\partial T}{\partial z} ,\) here σ* represent for Stefan–Boltzmann constant as well as k* symbol for the coefficient of mean absorption.

The governing equations of continuity, momentum, energy as well as concentration are (Ming et al.7) as:

The BCs are:

and \({\upmu }\) is the Cross fluid viscosity model and is defined as;

Similarity transformations

This section is about to defined the similarity transformations for the conversion of the aforementioned set of PDE’s in to ODE’s (Ming et al.7), i.e.,

By plugging Eq. (13) in Eqs. (5), (6), (7), (8), (9), (10), (11) are reduced as:

where, \(A = \left[ {1 + \left( {\sqrt {\left\{ {\Gamma_{r}^{2} \left( {F^{{^{{\prime}{2}} }} + G^{{^{{\prime}{2}} }} } \right)} \right\}} } \right)^{n} } \right]^{ - 1}\) and \(B = - n\Gamma_{r}^{2} \left[ {1 + \left( {\sqrt {\left\{ {\Gamma_{r}^{2} \left( {F^{{^{{\prime}{2}} }} + G^{{^{{\prime}{2}} }} } \right)} \right\}} } \right)^{n} } \right]^{ - 1} .\)

Subjected to the BC’s as:

The physical controlling factors are defined in the subsequence table.

Symbol | Description | Mathematical form |

|---|---|---|

Nb | Brownian motion factor | \(\tfrac{{\tau D_{B} (C_{w} - C_{\infty } )}}{\nu }\) |

Nt | Thermophoretic factor | \(\tfrac{{\tau D_{T} (T_{w} - T_{\infty } )}}{{\nu T_{\infty } }}\) |

Rd | Radiation factor | \(- \;\,\tfrac{{4\sigma^{ * } T_{\infty }^{3} }}{{3k(\sigma_{r} + \sigma_{s} )}}\) |

θw | Temperature ratio factor | \(\tfrac{{T_{w} }}{{T_{\infty } }}\) |

Sc | Schmidt number | \(\tfrac{\nu}{D_{B} }\) |

Pr | Prandtl number | \(\tfrac{\mu_{o}c_{p}}{{k_{o} }}\) |

kr | Chemical reaction factor | \(\tfrac{{R_{c} \;R}}{\Omega }\) |

Physical quantities

The skin friction coefficient, Nusselt number as well as Sherwood number which are defined, respectively, as:

The same may be changed into a form that can be solved as follows:

Comparison of the new work with literature

The viscosity of the entire procedure is the subject of this investigation; a tabular comparison is shown in precedents. Specifically, the results align with the work published by Ming et al.7 and Yin et al.35, as demonstrated in table 1.The mathematical modeling validation, i.e., for Rd = 0, \(N_{b} = 0,\) \({\text{Pr}} = 6.2\), \(N_{t} = 0,\) and another parameters are equal to one.

Solution procedures

The solution procedure for the modified improved BVP4C method in MATLAB involves several key steps. First, the boundary value problem (BVP) is defined by specifying the ODEs and the corresponding BCs. The modified improved method leverages the built-in MATLAB function BVP4C to discretize the problem, but with enhanments that include the use of a more accurate collocation approach and finite difference method for refining the initial guess. The procedure begins by setting up the Eqs. (6–10) and Eq. (11) in the appropriate format for BVP4C. Then, an initial guess for the solution is generated, which is iteratively improved using the finite difference approach to ensure convergence and accuracy. The Lobato III-stage formula is employed to guide the iterative corrections, improving the precision of each approximation. During the solution process, the tolerance level and CPU time are adjusted to balance between computation efficiency and solution accuracy. The final result is a highly accurate and convergent solution to the BVP, with significantly reduced computation time compared to traditional methods. To get the intended results, the following actions must be performed.

Description of new findings

One of the classical fluid mechanics issues of both theoretical and practical significance is the fluid flow problem over a revolving disk. Many studies on flow over a rotating disk have been conducted in theoretical fields. Most of these outcomes are related to the liquid velocity, temperature, pressure, and concentration, respectively. However, all the findings are properly, addressed by varying different physical parameters. For instance, the relaxation time constant, power law index \(\left( n \right),\) Browning motion factor \(\left( {N_{b} } \right)\). , thermoporetic factor \(\left( {N_{t} } \right),\) radiation factor \(\left( {R_{d} } \right)\) chemical reaction factor \(\left( {k_{r} } \right).\) The parameters’ fixed values for the whole approximate findings are as follows:

Figure 2(a-d) demonstrates the behavior of the \(\Gamma\) on \(F\left( \eta \right),\,H\left( \eta \right),G\left( \eta \right)\) and \(P\left( \eta \right)\) is both conduct. With variation in relaxation time constant (\(\Gamma )\) then \(F\left( \eta \right),\,G\left( \eta \right),\,H\left( \eta \right)\) as well as \(P\left( \eta \right)\) of the fluid are uplifted. Physically, the dynamical response of fluids to altered flow conditions is largely determined by the relaxation time constant. Its physical impact on radial tangential velocity and azimuthal velocities and pressure dependon the rheological features of the liquid and the specific characteristics of the flow system under consideration. The influence of Pr, Rd, Nt and Nb on the θ(η) is displayed via Fig. 3(a-d). When the values of Prandtl number rise then temperature is reduced, but temperature boost when thermal radiation raised. Physically, both the Prandtl number and thermal radiation have significant impacts on temperature distributions in fluid flow and heat transfer scenarios, which are influencing the behavior of heat transfer and fluid motion, and leading to a diverse temperature profiles depending on the specific characteristics of the system. Momentum diffusivity divided by thermal diffusivity is known as the Prandtl number. The thermal boundary layer becomes thinner when Pr is high because thermal diffusivity is low. The temperature drops as a result. The presence of thermal radiation alters the temperature profiles within a fluid. Higher radiation factor can lead to steeper temperature gradients, meaning that the temperature can change more rapidly over a short distance. This effect is crucial in applications like cooling systems or thermal insulation, where managing temperature distribution is essential for efficiency. The influence of Nt and \(N_{b}\) on the temperature is shown in Fig. 3(c, d). It is evident from the aforementioned statistics that the temperature increases as Nt as well as Nb values rise. Physically, both the thermophoretic parameter and Brownian motion factor have significant physical impacts on temperature distributions. A more even temperature field may result from more particle mixing brought on by stronger Brownian motion. This is especially crucial in nanofluids because the nanoparticles there show a lot of Brownian motion, which improves thermal conductivity and heat transmission effectiveness. The presence of thermophoretic forces can alter the temperature profiles within a fluid. As particles move towards cooler regions, they can effectively transport heat away from hotter areas, leading to enhanced cooling in those regions. This effect is particularly relevant in applications involving nano-fluids, where the manipulation of particle distribution can optimize thermal performance. The significant impact of Sc and \(k_{r}\) on concentration of the liquid is plotted seen in Fig. 4(a, b). It is cleared that when the values of Sc as well as kr is uplifted, then the liquid concentration is be decreased. Physically, the Schmidt number overshoot, the concentration profile tends to become more peaked near the source of the solute, indicating that the solute is less dispersed throughout the fluid. This behavior can be visualized in concentration distribution graphs, where higher Schmidt numbers show sharper peaks compared to lower values. The behavior of the chemical reaction factor can lead to distinct concentration layers within the fluid, which can be critical for processes such as catalysis or biochemical reactions. The effects of Rd, Pr,\(N_{t}\) and \(N_{b}\) on the Nusselt number are shown in Fig. 5(a-d), when the values of \(Rd\) as well as \({\text{Pr}}\) enhanced, then the Nusselt number of system is uplift. Physically, both \(Rd\) and \({\text{Pr}}\) is playing a key role in convective heat transfer. Radiation factor influences the rate of heat transfer in a system. As the radiation factor increases, it typically leads to enhanced heat transfer rates. This is particularly evident in scenarios involving high-temperature gradients, where thermal radiation becomes a dominant mode of heat transfer. The rate of heat transfer can be significantly affected by the intensity of radiation emitted or absorbed by surfaces. The behavior of \(N_{t}\) and \(N_{b}\) on the rate of heat transfer is shown in Fig. 5(c-d). When the values of \(N_{t}\) and \(N_{b}\) are boosted, then the rate of heat transfer is reduced. Physically, upraised Brownian motion can enhance heat transfer rates. The random motion of particles helps to distribute thermal energy more effectively throughout the fluid. This effect is particularly pronounced in systems where nanoparticles are present, as their motion can significantly improve the overall thermal performance of the fluid. Thermophoretic forces can enhance heat transfer rates in systems where temperature gradients are present. By promoting the movement of particles towards cooler areas, these forces can facilitate better thermal mixing and energy distribution within the fluid. Table 2 shows the effect of time relaxation constant (\(\Gamma )\) for radial velocity and tangential velocity on local skin friction, when we increasing the relaxation time constant \(\left( \Gamma \right),\) then the skin friction also raised. Physically, the relaxation time constant for radial and tangential velocities describe the rate at which velocity deviations relax towards equilibrium conditions, thereby affecting local skin friction, especially in regions with significant velocity gradients. For analysis of these effects in terms of predicting on and optimization the flow behavior in various engineering applications. Table 3 shows the effect of Sc as well as chemical \(k_{r}\) on Sherwood number. When the Sc as well as \(k_{r}\) are enhanced, then the Sherwood number Sc also enhanced. Physically, the Schmidt number as well as chemical reaction factor permanently influenced the mass transfer rates as well as consequently affect the Sherwood number, which characterizes convective mass transfer enhancement relative to diffusive mass transfer. For better understanding the study of these parameters are essential for optimizing mass transfer processes in various engineering practical procedures. Through Fig. 6(a, b), by following these steps and considerations, we can effectively find and analyze the residual errors between exact solution Imayama36 as well as numerical solutions, leading to improved understanding and refinement of the numerical methods.

Conclusion

The existence of the generalized nonlinear material on a typical rotating disk with a nonzero curl of the associated velocity field has been investigated in this work. The material’s motion has been described with the additional physical features of Brownian motion, radiation, thermophoretic forces, and first-order chemical reactions. The theme of the entire work has been focused on exploring the significant nature of the rotating flow. Furthermore, the flow phenomenon has been demonstrated with the significant features of laminar drag force, mass, and heat rate flows. Validation of the method has been effectively demonstrated by providing an excellent comparison with the published work. The main findings are collected in the following bullet list.

-

The radial component of the Cross liquid rotational motion has been noticed with declined behavior for the higher variation in the time relaxation feature.

-

The percentile maximum values of the time relaxation factor has been caused a reduction in the azimuthal flow speed and a reverse trends has been noticed while plotting the pressure.

-

The thermphoretic forces and Brownian motion has been impacted significantly while graphically visualizing the thermal status of the material.

-

The higher Schmidt number and reaction rate have been reduced the physical nature of the nanoparticle volume fraction.

-

The heat flow rate has been reduced by the higher values of thermophoretic and Brownian factors, respectively.

-

The drag force and rate of mas flow have been amplified with the variation in relaxation and Schmidt number respectively.

Data availability

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- Ω:

-

Angular velocity [LT−1]

- μ:

-

Dynamic viscosity [ML−1T−1]

- σ*:

-

Stephen-Bolzmann constant [MT−3 K−4]

- θw:

-

Temperature ratio factor [-]

- ρ:

-

Density fluid [ML−3]

- \(\nu\) :

-

Kinematic viscosity [L2L−1]

- ∇:

-

Del operator [-]

- τ:

-

Shear stress [NL−2]

- σ:

-

Electrical conductivity [SL−1]

- \(\Gamma\) :

-

Relaxation time constant [T]

- η:

-

Dimensionless variable [-]

- θ:

-

Dimensionless temperature[-]

- ϕ:

-

Dimensionless concentration [-]

- γ* :

-

Shear strain [-]

- \(A_{1}\) :

-

First Rivlin-Ericksen tensor

- \(B_{o}\) :

-

Strength of magnetic field [NL−1A−1]

- \(C\) :

-

Concentration

- \(C_{w}\) :

-

Wall solute concentration

- \(C_{\infty }\) :

-

Ambient concentration

- \(C_{p}\) :

-

Specific heat capacity [JK−1]

- \(D_{B}\) :

-

Brownian diffusion coefficient [L2T−1]

- \(D_{T}\) :

-

Thermophoretic diffusion coefficient [L2T−1]

- \(F,G,H\) :

-

Dimensionless functions

- \(k\) :

-

Thermal conductivity [WL−1 K−1]

- \(k_{r}\) :

-

Chemical reaction factor [-]

- \(k^{*}\) :

-

Mean absorption coefficient [L−1]

- M:

-

Magnetic factor [-]

- \(n\) :

-

Power law index

- \(N_{b}\) :

-

Brownian motion factor

- \(N_{t}\) :

-

Thermophoretic factor

- P:

-

Pressure [kgm−1 s−2]

- \(Rd\) :

-

Thermal radiation factor

- \(q_{r}\) :

-

Radiative heat flux [ML0T3]

- \(Sc\) :

-

Schmidt number

- T:

-

Temperature of the fluid [Θ]

- \(u,v,w\) :

-

Velocity components [L1T−1]

- \(T_{w} , T_{\infty }\) :

-

Wall and upstream temperatures [Θ]

- \(\vec{V}\) :

-

Vector velocity [L1T−1

References

Karman, T. V. Uber laminare und turbulente Reibung. Z. Angew. Math. Mech. 1(4), 233–252 (1921).

Turkyilmazoglu, M. Effects of uniform radial electric field on the MHD heat and fluid flow due to a rotating disk. In. J. Eng. Sci. 51, 233–240 (2012).

Griffiths, P. T. Flow of a generalized Newtonian fluid due to a rotating disk. J. Nonnewton Fluid Mech. 221, 9–17 (2015).

Mustafa, M. MHD nanofluid flow over a rotating disk with partial slip effects: Buongiorno model. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 108, 1910–1916 (2017).

Lv, Y. P., Gul, H., Ramzan, M., Chung, J. D. & Bilal, M. Bioconvective Reiner-Rivlin nanofluid flow over a rotating disk with Cattaneo-Christov flow heat flux and entropy generation analysis. Sci. Rep. 11(1), 15859 (2021).

Sharma, K., Kumar, S., Narwal, A., Mebarek-Oudina, F. & Animasaun, I. L. Convective MHD fluid flow over stretchable rotating disks with Dufour and Soret effects. Int. J. Appl. Comput. Math. 8(4), 159 (2022).

Ming, C., Liu, K., Han, K. & Si, X. Heat transfer analysis of Carreau fluid over a rotating disk with generalized thermal conductivity. Comput. Math. Appl. 144, 141–149 (2023).

Alkuhayli, N. A. M. Heat transfer analysis of a hybrid nanofluid flow on a rotating disk considering thermal radiation effects. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 49, 103131 (2023).

Mahmud, K., Duraihem, F. Z., Mehmood, R., Sarkar, S. & Saleem, S. Heat transport in inclined flow towards a rotating disk under MHD. Sci. Rep. 13(1), 5949 (2023).

Kanwal, S. et al. Insight into the dynamics of heat and mass transfer in nanofluid flow with linear/nonlinear mixed convection, thermal radiation, and activation energy effects over the rotating disk. Sci. Rep. 13(1), 23031 (2023).

Sus, C. Enhancing thermal conductivity of fluids with nanoparticles, developments and applications of non-Newtonian flows. ASME FED MD 231, 99-I05 (1995).

Ramzan, M. et al. Karman rotating nanofluid flow with modified Fourier law and variable characteristics in liquid and gas scenarios. Sci. Rep. 11(1), 16442 (2021).

Dharmaiah, G., Mebarek-Oudina, F., Kumar, M. S. & Kala, K. C. Nuclear reactor application on Jeffrey fluid flow with Falkner-skan factor, Brownian and thermophoresis, non linear thermal radiation impacts past a wedge. J. Indian Chem. Soc. 100(2), 100907 (2023).

Hussain, A., Raiz, S., Hassan, A., Ali, M. R. & Saeed, A. M. Bioconvective hybrid flow with microorganisms migration and Buongiorno’s model under convective condition. Front. Heat Mass Transf. 22(2), 433–453 (2024).

Bilal, S., Hussain, A. & Arshad, T. Scrutiny of pseudoplastic nanofluid flow under the influence of magnetic hydrodynamics with chemical reaction across the cylinder with slip boundary condition. Int. J. Therm. 24, 100848 (2024).

Palencia, J. L. D. et al. ANFIS-PSO analysis on axisymmetric tetra hybrid nanofluid flow of Cu-CNT-Graphene-Tio2 with WEG-Blood under linear thermal radiation and inclined magnetic field: A bio-medicine application. Heliyon 11(1), e41429 (2025).

Lakshmi, B. N., Dharmaiah, G., Anjum, A. & Naheed, M. Influence of Darcy-Forchheimer Fe3O4-CoFe2O4-H2O hybrid nanofluid flow with magnetohydrodynamic and viscous dissipation effects past a permeable stretching sheet: a numerical contribution. Multiscale Multidiscip. Model. Exp. Des. 8(1), 115 (2025).

Afridi, M. I., Dharmaiah, G., Prasad, J. L. R. & Vedavathi, N. Theoretical analysis of MHD Maxwell two phase nano flow subject to viscous dissipation and chemical reaction: A nonsimilar approach. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 65, 105688 (2025).

Liu, D. D. et al. Physics-informed neural networks for phase-field simulation in designing high energy storage performance polymer nanocomposites. Appl. Phys. Lett. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0244002 (2025).

Zhu, S., Wu, S., Fu, Y. & Guo, S. Prediction of particle-reinforced composite material properties based on an improved Halpin-Tsai model. AIP. Adv. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0206774 (2024).

Mebarek-Oudina, F., Dharmaiah, G., Prasad, J. R., Vaidya, H. & Kumari, M. A. Thermal and flow dynamics of magnetohydrodynamic Burgers’ fluid induced by a stretching cylinder with internal heat generation and absorption. Int. J. Therm. 25, 100986 (2025).

Aljedani, J. et al. Computational work of casson rheology on 3D swirling plate employing yamada-ota and xue models. Results Eng. 24, 102876 (2024).

Cross, M. M. Rheology of non-Newtonian fluids: a new flow equation for pseudoplastic systems. J. Colloid Sci. 20(5), 417–437 (1965).

Hauswirth, S. C. et al. Modeling cross model non-Newtonian fluid flow in porous media. J. Contam. Hydrol. 235, 103708 (2020).

Awais, M. & Salahuddin, T. Radiative magnetodydrodynamic cross fluid thermophysical model passing on parabola surface with activation energy. Ain Shams Eng. J. 15(1), 102282 (2024).

Acharya, N. Spectral simulation to investigate the effects of active passive controls of nanoparticles on the radiative nanofluidic transport over a spinning disk. J. Therm. Sci. Eng. Appl. 13(3), 031023 (2021).

Shah, F., Hayat, T. & Alsaedi, A. Entropy optimization in a fourth grade nanofluid flow over a stretchable Riga wall with thermal radiation and viscous dissipation. Int. Comm. Heat Mass Transfer 127, 105398 (2021).

Mahmood, Z. et al. Analysis of heat generation and viscous dissipation with thermal radiation on unsteady hybrid nanofluid flow over a sphere with double-stratification: Case of modified Buongiorno’s model. J. Rad. Res. Appl. Sci. 17(4), 101146 (2024).

Hussain, M., Rasool, M. & Mehmood, A. Radiative flow of viscous nano-fluid over permeable stretched swirling disk with generalized slip. Sci. Rep. 12(1), 11038 (2022).

Noreen, S. et al. Comparative study of ternary hybrid nanofluids with role of thermal radiation and Cattaneo-Christov heat flux between double rotating disks. Sci. Rep. 13(1), 7795 (2023).

Elboughdiri, N., Nazir, U., Sohail, M. & Abd Allah, A. M. Combine thermal performance based on dust particles and Hall and ion slip currents including tetra-hybrid nanoparticles on Howarth’s wavy pipe. Res. Eng. 23, 102666 (2024).

Sohail, M., Abodayeh, K. & Nazir, U. Implementation of finite element scheme to study thermal and mass transportation in water-based nanofluid model under quadratic thermal radiation in a disk. Mech. Time Depend. Mater. 28(3), 1049–1072 (2024).

Li, X. et al. Stretchable and leakage-free liquid metal networks for thermal management. Adv. Funct. Mater. https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.202420839 (2025).

Yang, J., Fu, L. Y., Han, T., Deng, W. & Fu, B. Y. Thermoacoustoelasticity for elastic wave propagation in preheated and prestressed solid rocks. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00603-024-04361-z (2025).

Yin, C., Zheng, L., Zhang, C. & Zhang, X. Flow and heat transfer of nanofluids over a rotating disk with uniform stretching rate in the radial direction. Prop. Pow. Res. 6(1), 25–30 (2017).

Imayama, S. Experimental study of the rotating-disk boundary-layer flow (KTH Royal Institute of Technology, 2012).

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their appreciation to the Deanship of Research and Graduate Studies at King Khalid University for funding this work through Large Research Project under grant number (R. G. P. 1/104/45). Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2025R52), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. The authors extend their appreciation to the Deanship of Scientific Research at Northern Border University, Arar, KSA for funding this research work through the project number “NBU-FFR-2025-2570-12”.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The contribution of all authors during the revision and initial submission is stated as under: 1. Dr. Latif Ahmad (a) Supervision (b) Conceptualization (c) Finalization of the newly developed problem 2. Dr. Umair Khan (a) Modification of the results and discussion section (b) Problem description (c) Edited the whole manuscript for mathematical and technical mistakes 3. Dr. Aisha M. Alqahtani (a) Method implementations (b) Utilization of academic writing expertise (c) Physical and chemical analysis of the results (d) Modification of the results and discussion section (e) Problem description (f) Edited the whole manuscript for mathematical and technical mistakes 4. Dr. Marouan Kouki (a) Modification of graphical results (b) Conclusion modification (c) Utilization of numerical methods and validation of the results 5. Dr. Essam H. Ibrahim (a) Coding expertise for the nonlinear problems (b) Highlighting the main findings of the study 6. Mr. Zuhaib Hamid (a) Wrote the original draft b) Modeling and formulations 7. Mr. Saleem Javed (a) Numerical analysis (b) Visualization.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ahmad, L., Khan, U., Alqahtani, A.M. et al. Numerical analysis of electrochemically radiative and higher thermally conductive nanomaterials spinning motion due to rotating disk. Sci Rep 15, 12601 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-95835-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-95835-9

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Thermal energy transport features of hybrid nanomaterials past a moving thin needle

Journal of Thermal Analysis and Calorimetry (2025)