Abstract

Multimedia recommendation has emerged as a pivotal area in contemporary research, propelled by the exponential growth of digital media consumption. In recent years, the proliferation of multimedia content across diverse platforms has necessitated sophisticated recommendation systems to assist users in navigating this vast landscape. Existing research predominantly centers on integrating multimodal features as auxiliary information within user–item interaction models. However, this approach proves inadequate for an effective multimedia recommendation. Primarily, it implicitly captures collaborative item–item connections via high-order item–user–item associations. Given that items encompass diverse content modalities, we suggest that leveraging latent semantic item–item structures within these multimodal contents could significantly enhance item representations and consequently augment recommendation performance. Existing works also fail to effectively capture user–user affinity in multimedia recommendations as they only focus on improving the item representation. To this end, we propose a novel framework where we capture the latent features of different modalities and also consider the user–user affinity to solve the Recommendation System (RecSys) problem. We have also incorporated the cold-start study in our experiments. We did an extensive experiment over three publicly available datasets to demonstrate the efficacy of our framework over the state-of-the-art model.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As the Internet continues to evolve at a rapid pace, recommender systems have emerged as essential aids in guiding users to pertinent information. In today’s digital landscape, users encounter vast volumes of online content spanning various modalities like images, text, and videos. This has fueled increased scholarly attention towards multimedia recommendation in recent times. This field focuses on forecasting user engagement with items featuring multiple modes of content. Remarkably, its effective implementation has permeated a wide array of online platforms, encompassing areas such as online marketplaces, streaming video platforms, and collaborative content-sharing networks.

Broadly speaking, recommender systems are categorized into two main approaches: collaborative filtering (CF)1,2,3 and content-based filtering (CBF)4. Collaborative filtering analyzes user–item interactions and similarities among users or items to generate recommendations. In contrast, content-based filtering focuses on the attributes of items and user preferences to make suggestions. Hybrid approaches5, combining elements of both methods, have also gained popularity, offering enhanced recommendation accuracy and coverage. These distinct methodologies cater to diverse user preferences and information needs, playing crucial roles in various domains such as e-commerce, entertainment, and information retrieval. Works such as VBPR6 and ACF7 have extended the CF-based methods by incorporating multimedia contents, but they have used the multimodal information as side information and didn’t capture the item–item relationship between different modalities. Most of the traditional CF-based methods suffer from the cold-start problem8 for new users and items. However, CBF-based methods handle the cold-start problem for a new item, but it suffers for a new user.

Graph Neural Network (GNN)9,10 has been a remarkable success in recent years. Inspired by this, the authors in11 have constructed a bipartite graph to model the user–item relationship and improve the item representation. The state-of-the-art performance in recommender systems mostly uses graph-based recommender systems. User–item relationships have also been captured in12 by creating modality-specific user–item graphs.

There are three major limitations in the existing works: (1) Giving equal preferences to all the modalities for modeling the user–item relationship. Most of the graph-based recommender systems12,13,14 assign equal preference to all the modalities, but it is not always true as it depends upon different scenarios. For example, if a person is interested in buying books, the visual features might be less appealing than textual features, and on the other hand, when buying clothes, visual features are more predominant than textual features. Hence, we can not treat all the modality contributions to be the same in every scenario. (2) Initial representation of a user. It is clear that current works use random ID embedding to represent a user. However, it can be represented with the help of items it has interacted with in the past, and this will give a much better and more meaningful representation to a user. (3) Latent feature of user–user relationship. Studies such as15,16 only focus on improving the item–item relationship but fail to capture the latent feature of user–user affinity. In order to have novel and serendipity recommendations, it is essential to capture user–user relationships.

In this work, we have focused on solving these limitations and proposed a novel framework for multimedia recommendation. In summary, our contributions can be stated as:

-

We have proposed a novel framework to capture the latent features of different modalities, which are helpful in discovering candidate items.

-

We emphasized the significance of harnessing user relationships in multimedia recommendations, which complement the collaborative signals captured by conventional CF methods.

-

We confirmed the effectiveness of our proposed model through comprehensive experimentation on three openly accessible datasets.

Related works

Collaborative filtering (CF) has seen considerable success in recommendation systems, utilizing user feedback like clicks and purchases to forecast user preferences and offer suggestions. Nevertheless, CF approaches encounter challenges with sparse data characterized by limited user–item interactions and infrequently accessed items. To tackle data sparsity, it’s crucial to utilize additional information beyond user–item interactions. Multimodal recommendation systems delve into vast multimedia content details of items, finding applications across diverse domains like e-commerce, instant video platforms, and social media platforms17,18.

Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) have emerged as powerful tools for analyzing data structured in graphs and have found widespread application in various domains, including but not limited to node classification19, link prediction20, and information retrieval21. Despite their effectiveness, many GNN methods are highly reliant on the quality of the underlying graph structure, often necessitating the availability of a meticulously constructed graph, which is often unattainable in real-world scenarios22. The recursive nature of GNNs, where information is aggregated from neighboring nodes to compute node embeddings, worsens this sensitivity to graph quality, as even minor perturbations can propagate throughout the network, impacting the embeddings of numerous nodes. Moreover, in many practical scenarios, initial graph structures are absent altogether. Consequently, a significant body of research has emerged focusing on Graph Structure Learning (GSL), which aims to simultaneously learn optimized graph structures and corresponding representations. GSL methods can be broadly categorized into three groups: metric learning23, probabilistic modeling24, and direct optimization approaches25. We referred to this26, for recent graph structure learning. Authors in27 propose an AR-based visualization system that integrates multi-modal interactions, including vision, touch, eye-tracking, and sound, to enhance decision-making and user engagement.

Heterogeneous information network (HIN)-based recommenders have gained attention due to their ability to capture rich semantics, but many existing methods struggle to model heterophily and logical reasoning in recommendations. Authors in28 propose SLHRec, a structure- and logic-aware heterogeneous graph learning framework for recommender systems. It leverages network geometry to model heterophily in HINs and integrates Markov logic networks (MLN) for logical reasoning, enhancing recommendation performance. In29, the authors provide a comprehensive survey on the integration of Large Language Models (LLMs) with recommender systems, highlighting their mutual enhancement. The study explores LLM-based architectures for recommendation, the role of recommender systems in improving LLM agents, and key challenges such as safety, explainability, fairness, and privacy.

Within personalized recommendation systems, while the interactions between users and items can be naturally depicted as a bipartite graph, the connections between items themselves often go unexplored. To explicitly capture these item–item relationships, we adopt metric learning techniques to encode edge weights as a measure of distance between two nodes, aligning well with multimedia recommendation scenarios where detailed content information can be leveraged to gauge the semantic relationship between distinct items.

Motivation

The rapid proliferation of multimedia content across various online platforms has led to a pressing need for sophisticated recommendation systems that can efficiently assist users in navigating this vast and diverse landscape. Traditional recommendation systems predominantly focus on either collaborative filtering or content-based filtering, often treating multimodal information as supplementary side features rather than integrating it effectively into the core recommendation process. This approach fails to capture the nuanced relationships that exist between different modalities of items, such as textual descriptions and visual attributes, which are crucial for making accurate recommendations in scenarios involving complex user preferences.

Furthermore, existing methods12,13,30 often overlook the importance of capturing user–user affinity, concentrating primarily on item representations. This limitation hinders the ability to generate serendipitous and novel recommendations that go beyond immediate user interests. Additionally, most graph-based recommendation models give equal importance to all modalities, which might not always be appropriate depending on the context. For instance, while textual information may be more relevant when recommending books, visual features could be more critical for fashion items.

To address these gaps, we propose a novel framework that not only captures the latent features of multiple modalities but also incorporates user–user relationships, allowing for a more comprehensive representation of user preferences. By leveraging graph structure learning and adaptive multimodal fusion, our model dynamically balances the contributions of different modalities based on contextual relevance, thereby improving recommendation performance. This work aims to advance the state-of-the-art in multimodal recommendation by providing a robust solution that effectively utilizes all available information to generate more accurate and diverse recommendations, even in cold-start scenarios.

Dataset

Experimentation was done as outlined by18 on three datasets provided by Amazon. (a) Baby (b) Clothing, Shoes, and Jewelry, and (c) Sports and Outdoors. For brevity, we’ll refer to these categories collectively as Baby, Clothing, and Sports. The statistics of the dataset in shown in Table 1.

Problem statement

Let us denote the set of users and items with U, I, respectively. Each user \(u \in U\) has interacted with \(I_u\) items. Since every interaction is a form of positive feedback, \(y_{ui} = 1\) for \(i \in I_u\). \(x_i \in \mathbb {R}^d\) denotes the item id embedding, where d is the embedding dimension. The modality feature of item i is denoted as \(e^m_i \in \mathbb {R}^d_m\), where \(d_m\) represents the dimension of features, \(m \in M\) is the modality, and M is the set of modalities. In this paper, \(M = \{v,t\}\) is restricted to two modalities. However, our approach can be extended to multiple modalities too.

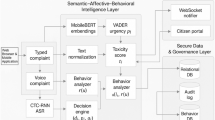

Methodology

This section is divided into two parts: first, we will discuss about the embedding generation of different modalities of items and users. Secondly, we will discuss about the proposed architecture. The overview of the proposed architecture is shown in Fig. 1.

Embedding generation

Textual embedding

Every item in the dataset consists of a title, description, category, and brand. We concatenated all the information and used sentence-transformers to extract textual features. We obtained a feature vector of \(\mathbb {R}^{1\times 1024}\) dimensions.

Visual embedding

The images provided in the dataset were blurred, and hence when we passed it to Resnet50 to extract embeddings, it consisted of less information. Inspired by authors in31, we proposed a visual embedder to generate task-specific visual embedding for each item. We trained our embedder on all three datasets and extracted the embedding from the second last hidden layer to get the dimension of \(\mathbb {R}^{1\times 1024}\) for each item.

User embedding

Most of the existing approaches use random user-ID embedding for its representation. But since every user has a history of items associated with it, we can represent it with the help of those items which will carry more information to the user representation. We have considered the textual embedding of each item the user has interacted with and finally calculated the mean of all those textual embeddings. Mathematically, it can be denoted as:

where \(m_i\) represents the textual features of movie m and M is the total number of movies user u has interacted with.

Learning latent structure for user and item

Multimodal features offer valuable and intricate content insights for items. However, existing methods merely treat these features as supplementary information for each item, disregarding the crucial relationships embedded within them. In this section, we have discussed how we have created a graph for user–user and item–item relationships from initial features. Also, we have transformed our initial features into high-level features to construct the learned graph. Finally, we aggregated these features from different modalities in an adaptive way.

Initial graph construction

Using textual and visual features as discussed in “Textual embedding” and “Visual embedding” sections respectively, we created a similarity graph \(S^m\) for each modality m. For user features, as discussed in “User embedding” section, we constructed a similarity graph \(S^u\). For node similarity measure, there are options such as attention mechanism23, kernel-based functions32, and cosine similarity33. Any method can be used for similarity measurement for our framework, and here, we have opted to use cosine similarity. Mathematically, \(S^u \in \mathbb {R}^{M\times M}\) and \(S^m \in \mathbb {R}^{N\times N}\) where M is the total number of users and N is the total number of movies are defined as follows:

where i,j are items and x,y are users.

Once we obtained \(S^m\) and \(S^u\) matrices, we further applied kNN sparsification because these graphs are very sparse and contain edges that lead to noise and are computationally demanding. Since cosine similarity ranges from [− 1, 1], and the graph edge should be non-negative, so we converted the negative entries to zero. For each item i and user x, we only kept edges with top-\(k_{item}\) and top-\(k_{user}\) confidence scores respectively. Please note the value of k is different for user and item cases.

Transforming initial feature to construct learned graph

We have obtained \(S^m\) and \(S^u\) with the help of initial raw features provided by user and item. However, the initial features might be noisy or incomplete due the error prone data measurement and collection. In order to solve this issue, we transform the initial raw features into high level features as shown in Eq. (6).

where \(W_m \in \mathbb {R}^{d^{\prime} \times d_m}\), \(b_m \in \mathbb {R}^{d^{\prime}}\), \(W_u \in \mathbb {R}^{d^{\prime\prime} \times d_u}\), and \(b_u \in \mathbb {R}^{d^{\prime\prime}}\). Here, \(d^{\prime}\) and \(d^{\prime\prime}\) refer to the dimensions of high-level features of \(\tilde{e}^{m}_{i}\) and \(\tilde{e}^{u}_{x}\), respectively. Also, \(d_m\) and \(d_u\) refer to the dimensionality of modality m and user u, respectively. Once we have transformed the initial raw features, we followed the same approach as mentioned in “Initial graph construction” section to obtain \(\tilde{S}^{m}\) and \(\tilde{S}^{u}\) matrices for item and user, respectively.

To retain the comprehensive information from the original item graph and ensure the stability of the training procedure, we introduce a skip connection that merges the acquired graph with the initial graph:

Here \(A^m\) and \(A^u\) represent the final similarity matrix of the item and user, respectively. \(\lambda\) and \(\beta\) control the amount of information coming from the initial and learned graph.

To ensure numerical stability and improve message propagation in the GCN layers, we apply symmetric normalization to the adjacency matrix. Given an initial adjacency matrix A, we compute the normalized adjacency matrix \(\tilde{A}\) as:

where D is the degree matrix defined as:

This normalization technique prevents over-smoothing of node representations and ensures that the spectral properties of the graph are well-conditioned for stable training. It also helps control the scale of node features, leading to better convergence and improved recommendation performance.

Multimodal fusion

Multimodal fusion plays an important role in developing an effective recommendation system since the fusion should be able to complement each other and carry out effective features to represent an item. Here, we have two modalities which are text and visual. The simple concatenation will yield more computation and might not be an efficient approach. Fusion should be such that it depends on the item which modality to prefer or give more weightage while recommending that item. Therefore, we assigned learnable weights to each modality so that we could get different importance scores in an adaptive way. Mathematically it can be represented as:

where \(\alpha _m\) denotes the weight given to each modality and \(A \in \mathbb {R}^{N\times N}\) is the similarity or adjacency matrix. Here, \(\sum ^{|M|}_{i=1}\alpha _m = 1\) as we have applied softmax function to keep matrices normalized.

Graph convolution

Once we acquire the latent structures, we apply graph convolution operations34 to enhance item representations by incorporating item–item relationships into the embedding process. Graph convolutions function as message-passing and aggregation mechanisms. By disseminating item representations from neighboring items, an item can gather information from its immediate neighbors. Additionally, by layering several graph convolutional layers, the model can capture higher-order relationships between items.

Mathematically, in the l-th layer, message propagation for an item can be formulated as:

where \(h_i^{(l)}\) denotes the l-th layer representation and N(u) denotes the neighbour of item I. \(h_i^{(0)}\) is considered as initial random id embedding of item I.

Similarly for the user, in the l-th layer, message propagation for an item can be formulated as:

where \(h_u^{(l)}\) denotes the l-th layer user representation and N(u) denotes the neighbour of user U. \(h_u^{(0)}\) is considered as initial random id embedding of user U.

Experiments

In this section, we have answered the following Research Question (RQ):

-

RQ1: How does our proposed framework perform when utilizing different modalities (text-only, image-only, and multimodal fusion)?

-

RQ2: How does our proposed framework perform with the existing multimedia state-of-the-art models as well as traditional CF-based models?

-

RQ3: How effective is our proposed model under cold start settings?

-

RQ4: How much our model is sensitive to its parameters, such as \(k, \lambda , \beta\), which have been used in our experiments?

Optimzation

We employ the Bayesian Personalized Ranking (BPR) loss35 to assess pairwise rankings, encouraging the prediction of a seen entry to surpass its unseen counterparts. In mathematical terms, it is expressed as:

Here, \(I_u\) signifies the item with which user \(u \in U\) has interacted. The triplets (u, i, j) constitute the training sample, where i indicates the positive item, and j indicates the negative item with which the user has not interacted. \(\sigma (.)\) represents the sigmoid function.

Experimental settings

Our code has been implemented in PyTorch36, where the input dimensions of users and different modalities, including text and visual features, are set to 1024. We use the Adam optimizer37 with weight decay for regularization, and the learning rate is selected from {0.00001, 0.001, 0.005} based on validation performance. The batch size is fixed at 128 to ensure stable training while maintaining computational efficiency. Model parameters are initialized using the Xavier initializer38 to facilitate better weight distribution.

To fine-tune hyperparameters, we conducted a systematic grid search. The embedding dimension was varied among {64, 128, 256} to balance computational cost and representational power. The number of GCN layers was selected from {1, 2, 3}, ensuring sufficient feature propagation while preventing over-smoothing. The number of neighbors (k) retained in graph construction was chosen from {10, 20, 30, 50}, optimizing connectivity while mitigating noise. Dropout rates were experimented within {0.1, 0.3, 0.5} to improve generalization.

For model evaluation, we adopt rank-based metrics, including precision, recall, and Normalized Discounted Cumulative Gain (NDCG)12,13,30, with a cut-off value of \(k=20\). Experiments are conducted across multiple random seeds to ensure the robustness of results, and statistical significance is verified where applicable.

To ensure reproducibility, we will provide the full hyperparameter configurations and experimental details in the supplementary materials or source code.

Ablation studies (RQ1)

To analyze the contribution of different modalities in our model, we conduct an ablation study by evaluating the performance under three different configurations: (1) text-only, (2) image-only, and (3) the full model integrating both text and image features. The results are presented in Table 2.

-

Text-Only Performance: The model using only textual features achieves reasonable performance, indicating that textual descriptions provide meaningful signals for user preference modeling. However, the absence of visual features limits its effectiveness, particularly in categories where appearance plays a crucial role, such as Clothing. As a result, the recall and NDCG scores remain lower than the multimodal setup.

-

Image-Only Performance: The model incorporating only image features performs slightly better than the text-only variant, particularly in Clothing, where visual attributes are more influential in user decisions. The improvements are also noticeable in Sports and Baby categories, where product appearance contributes to user preferences. However, relying solely on visual data leads to a lack of contextual understanding, making recommendations less precise compared to the full model.

-

Text + Image (Full Model): The integration of both text and image features results in the highest performance across all datasets. The Clothing category benefits the most from visual cues, while textual descriptions help refine recommendations in Sports and Baby. This multimodal approach leverages the strengths of both data types, leading to significant improvements in recall, precision, and NDCG scores, confirming its effectiveness in enhancing recommendation quality.

These findings validate the effectiveness of our proposed multimodal approach, where both textual and visual features contribute complementary information, leading to a more accurate and robust recommendation system.

Baselines

In assessing the efficiency of our proposed model, we compare it against various benchmark recommendation models. These benchmarks can be categorized into two distinct groups: General models, which solely depend on interactive data for recommendation, and Multimedia models, which leverage both interactive data and multi-modal features for recommendation purposes.

(1) General Models:

-

MF1: It optimizes user and item representations through Bayesian personalized ranking (BPR) loss, focusing solely on direct user–item interactions. This classic collaborative filtering approach employs a matrix factorization framework to discern latent patterns within interaction data, enhancing recommendation accuracy without considering additional contextual information.

-

NGCF11: It employs a bipartite graph to explicitly represent user–item interactions. Utilizing graph convolutional operations, it facilitates the interaction between user and item embeddings, enabling the extraction of collaborative signals alongside higher-order connectivity cues.

-

LightGCN34: It simplifies GCN design for collaborative filtering, utilizing light graph convolution and layer combination. This approach prioritizes efficiency by avoiding unnecessary complexities like feature transformation and nonlinear activation, making it highly suitable for recommendation systems.

(2) Multimedia Models:

-

VBPR6: This model can be seen as an extension of the MF framework by incorporating visual features.

-

MMGCN12: The authors of this study developed modality-aware graphs to grasp various modality features. Additionally, they combine all modalities’ embeddings to derive the representation of an item.

-

GRCN13: This approach enhances existing GCN-based models by enhancing the user–item interaction graph. Through the incorporation of multimodal features, it enables the identification and elimination of false-positive interactions.

-

SLMRec30: This research stands as a cutting-edge approach wherein the authors have introduced a self-supervised framework. Striving to unveil the multimodal patterns of items, it devises a task-centered on node self-discrimination.

-

BM339: This study streamlines the framework by eliminating the necessity for randomly selected negative instances.

-

HCFAA40: This study introduces HCFAA, a hypergraph-based framework enhancing self-supervised recommender systems by capturing local and global collaborative relationships with adaptive augmentation.

Comparison with the state-of-the-art (SOTA) models (RQ2)

Table 3 demonstrates that our model outperforms all previous baselines, including both general and multimodal approaches, across all dataset categories. These results highlight the effectiveness of our proposed model in multimodal recommendation tasks. The best-performing results are highlighted in bold, while the second-best results are underlined for clarity.

For the clothing dataset, visual features play an important role, and hence, all the multimodal baselines, such as MMGCN, VBPR, and GRCN, showed better performance compared to non-multimodal models such as MF and NGCF. Explicitly capturing the item–item and user–user relationship has helped in overcoming models such as MMGCN, SLMRec, etc.

For the other two datasets, visual features might not play a more important role, and hence, the performance of general models and multimodal models are almost similar, or we can say that the improvement over general models is much less.

Cold-start study (RQ3)

The cold-start problem is a significant challenge in recommendation systems, particularly when new items or users are introduced to the system, and there is limited or no historical interaction data available. Traditional collaborative filtering models struggle in such scenarios as they rely heavily on user–item interactions for generating recommendations. This results in poor recommendation quality for new items (item cold-start) or new users (user cold-start). To address this issue, we exploit the multimodal features of items, such as textual descriptions and visual attributes, which are inherently available even for new entities.

Experimental setup

To simulate a cold-start scenario in our experiments, we prepared a modified dataset by removing user–item interactions involving randomly selected 20% unique items. These items, referred to as cold-start items, were excluded from the training data, ensuring that the model had no prior exposure to them during training. The remaining 80% of the data was used for training the model. During evaluation, we tested the model’s ability to recommend these cold-start items to users, using the holdout test set containing interactions with the 20% excluded items.

We employed the recall@k metric, where \(k\) is set to 20 by default, to measure the effectiveness of the model in ranking relevant items among the top 20 recommendations. This metric is well-suited for evaluating the cold-start performance, as it reflects the proportion of relevant items successfully retrieved from the unseen set of cold-start items.

Results and analysis

The results, illustrated in Fig. 2, demonstrate that our proposed model significantly outperforms all other baselines in the cold-start setting. The superior performance can be attributed to the model’s ability to learn comprehensive representations from multimodal features, thereby providing meaningful recommendations even in the absence of historical interaction data. By incorporating item–specific visual and textual features into the recommendation process, the model effectively mitigates the cold-start issue.

Models such as Matrix Factorization (MF), which depend solely on collaborative filtering, showed the lowest performance, as they lack the capacity to leverage content-based information in the absence of prior interactions. In contrast, content-based models, such as VBPR and MMGCN, demonstrated relatively better performance, validating the importance of utilizing item features like images and text. However, these models still fall short compared to our proposed method, as they do not fully exploit the latent structures between different modalities and user–user affinities. Note that in Fig. 2, the y-label denotes the recall@20% metric, and the x-label denotes the model.

Implications

The ability of our model to recommend cold-start items effectively has significant implications for real-world applications. For instance, in e-commerce platforms, new products are constantly being added, and ensuring their visibility to potential customers is crucial for business success. Similarly, in streaming services, recommending new movies or shows to users without historical data can enhance user engagement. Our approach not only improves the discovery of new items but also provides a balanced representation by considering user preferences and multimodal item characteristics.

Overall, the results indicate that integrating multimodal features with advanced graph learning techniques provides a promising solution to the cold-start problem, paving the way for more effective and comprehensive recommendation systems.

Parameter analysis (RQ4)

In this, we will discuss the hyperparameters such as \(k_{item}, k_{user},\lambda , \beta\). We have the following observations:

Effect of \(k_{\text {item}}\) and \(k_{\text {user}}\)

The parameters \(k_{\text {item}}\) and \(k_{\text {user}}\) determine the number of neighbors considered for constructing the initial similarity graphs for items and users, respectively. These parameters control the sparsity of the graph, influencing the amount of information aggregated from neighboring nodes.

-

Figure 3a,c,e shows that model performance improves when \(k_{item}\) is varied from 1 to 10 where \(k_{item}=0\) shows that model has no interaction with neighbors. However, when \(k_{item}\) is further increased from 10, the recall@20 starts decreasing as adding more information can be inferred as a noise to the main node. After the experimental finding, we set the value of \(k_{item}\) to be equal to 20.

-

We have observed the similar behavior of \(k_{user}\) as shown for \(k_{item}\). After the experimental finding, we set the value of \(k_{user}\) to be equal to 30.

Effect of \(\lambda\) and \(\beta\)

The parameter \(\lambda\) controls the contribution of the initial raw graph versus the learned graph in the final graph representation. It plays a critical role in maintaining a balance between the original feature space and the transformed, high-level features.

The parameter \(\beta\) is analogous to \(\lambda\) but controls the weighting between initial and learned features in the user graph. It ensures that user representations are robust and capture both initial and refined relationships.

-

Figure 3b,d,f shows that skip connection \(\lambda\) increases to a certain extent. When \(\lambda = 0\), it means we are considering only high-learned features, while \(\lambda = 1\) indicates we are considering only raw features. However, increasing \(\lambda\) further, we can observe performance start to deteriorate because raw features preparation starts to increase and it starts creating noise. After the experimental finding, we set the value of \(\lambda\) to be equal to 0.6 to get the maximum performance.

-

We have observed the similar behavior of \(\beta\) as shown for \(\lambda\). After the experimental finding, we set the value of \(\beta\) to be equal to 0.7.

Summary of findings

Our parameter analysis reveals that an optimal combination of \(k_{\text {item}} = 20\), \(k_{\text {user}} = 30\), \(\lambda = 0.6\), and \(\beta = 0.7\) yields the best performance. These values ensure that the model effectively balances the amount of neighborhood information, raw feature contributions, and learned feature enhancements, ultimately leading to improved recommendation quality. The insights gained from this analysis can guide future studies in fine-tuning similar parameters for graph-based recommendation systems, thereby enhancing their robustness and generalizability across different datasets and application domains.

Computational and storage complexity analysis

The proposed model integrates multimodal fusion and Graph Convolutional Networks (GCNs), which introduce computational and storage costs. To justify their feasibility, we analyze the time and space complexity of key components.

Time complexity analysis

The primary computational overhead arises from three key operations:

-

1.

Multimodal Feature Extraction:

-

Let N be the number of items, M the number of modalities, and d the feature dimension.

-

Textual and visual embeddings are extracted via pre-trained models (e.g., Sentence-Transformers and ResNet-50), which require \(O(N \cdot M \cdot d)\) operations.

-

Since feature extraction is performed offline, it does not affect real-time inference.

-

-

2.

Graph Construction and Learning:

-

The initial similarity graphs for users and items are computed using cosine similarity, which has a complexity of \(O(N^2 \cdot d)\).

-

Sparsification using k-nearest neighbors (kNN) reduces this complexity to \(O(N \cdot k \cdot d)\), where \(k \ll N\).

-

Learning the refined graph structure involves matrix multiplications, which require \(O(N \cdot d^2)\) operations.

-

-

3.

Graph Convolutional Network (GCN) Layers:

-

Each GCN layer involves aggregating features from neighbors, with time complexity \(O(|E| \cdot d)\), where |E| is the number of edges.

-

With L layers, the total complexity is \(O(L \cdot |E| \cdot d)\).

-

As |E| is limited by sparsification (i.e., \(|E| = O(N \cdot k)\)), the final complexity per layer is \(O(L \cdot N \cdot k \cdot d)\).

-

Overall Time Complexity: Summing up all components, the dominant term is \(O(L \cdot N \cdot k \cdot d)\), which scales linearly with N, making the method efficient for large-scale recommendations.

Space complexity analysis

The major storage requirements come from:

-

Feature Storage:

-

Each item stores multimodal embeddings, requiring \(O(N \cdot M \cdot d)\) space.

-

-

Graph Representation:

-

The adjacency matrix requires \(O(N \cdot k)\) space due to sparsification.

-

-

Model Parameters:

-

GCN parameters scale as \(O(L \cdot d^2)\), which is negligible compared to data storage.

-

Overall Space Complexity: The total storage requirement is \(O(N \cdot M \cdot d + N \cdot k + L \cdot d^2)\). Given that \(M, k, L \ll N\), this remains manageable.

Justification of computational costs

-

The proposed model scales linearly with N, making it feasible for large-scale datasets.

-

Sparsification ensures that graph computations remain efficient.

-

Feature extraction is performed offline, reducing inference time.

-

Empirical results confirm that training and inference times remain within practical limits.

Thus, our approach balances expressiveness and efficiency, making it suitable for real-world recommendation systems.

Conclusion and future works

In this manuscript, we have introduced an innovative framework for multimodal recommendation systems, leveraging graph structure learning to uncover latent connections between items based on their multimodal features. Our approach begins with the construction of similarity graphs that capture intricate patterns between users and items, followed by the creation of similar graphs using the learned item and user features. This hierarchical representation is then processed using a graph convolutional network for effective message propagation, ultimately forming comprehensive user and item representations.

Our experimental results demonstrate that the proposed framework significantly outperforms existing state-of-the-art models in both normal and cold-start scenarios. Specifically, our method achieves superior performance across multiple metrics, highlighting its robustness and effectiveness in capturing complex multimodal relationships. This performance gain is attributed to the novel incorporation of user–user and item–item affinity, as well as the adaptive multimodal fusion strategy that selectively emphasizes the most relevant content features based on context.

Despite the promising results, there are several avenues for future exploration. One potential direction is the integration of additional modalities, such as audio or social interactions, to further enhance the diversity of item representations. Moreover, incorporating temporal dynamics could provide a more holistic understanding of user preferences as they evolve over time.

Another promising extension is to explore advanced graph learning techniques, such as dynamic graph learning or self-supervised learning, to further refine the representation learning process. Additionally, it would be beneficial to evaluate the scalability and efficiency of the proposed model in large-scale real-world environments, which often present unique challenges such as extreme data sparsity and high-dimensionality.

Finally, enhancing interpretability remains an essential area of improvement. Developing methods to provide insights into the decision-making process of the recommendation model would not only build user trust but also enable better model diagnostics and refinement. Overall, our work sets the stage for more comprehensive and adaptive multimodal recommendation systems, and we believe that these future research directions can lead to even more powerful and user-centric recommender systems.

Data availability

The processed dataset is available at https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1sFg9W2wCexWahjqtN6MVc4f4dMj5hyFp.

References

Koren, Y., Bell, R. & Volinsky, C. Matrix factorization techniques for recommender systems. Computer 42, 30–37 (2009).

Charu, C. A. Recommender Systems: The Textbook (Springer, 2016).

He, X. et al. Neural collaborative filtering. In Proceedings of the 26th international conference on World Wide Web 173–182 (2017).

Van Meteren, R. & Van Someren, M. Using content-based filtering for recommendation. In Proceedings of the Machine Learning in the New Information Age: MLnet/ECML2000 Workshop, Vol. 30, 47–56 (2000).

Burke, R. Hybrid recommender systems: Survey and experiments. User Model. User-Adapted Interact. 12, 331–370 (2002).

He, R. & McAuley, J. Vbpr: Visual Bayesian personalized ranking from implicit feedback. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Vol. 30 (2016).

Chen, J. et al. Attentive collaborative filtering: Multimedia recommendation with item-and component-level attention. In Proceedings of the 40th International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval 335–344 (2017).

Lika, B., Kolomvatsos, K. & Hadjiefthymiades, S. Facing the cold start problem in recommender systems. Expert Syst. Appl. 41, 2065–2073 (2014).

Wu, S. et al. Session-based recommendation with graph neural networks. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Vol. 33, 346–353 (2019).

Zhang, M. et al. Personalized graph neural networks with attention mechanism for session-aware recommendation. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 34, 3946–3957 (2020).

Wang, X., He, X., Wang, M., Feng, F. & Chua, T.-S. Neural graph collaborative filtering. In Proceedings of the 42nd International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval 165–174 (2019).

Wei, Y. et al. Mmgcn: Multi-modal graph convolution network for personalized recommendation of micro-video. In Proceedings of the 27th ACM International Conference on Multimedia, 1437–1445 (2019).

Wei, Y., Wang, X., Nie, L., He, X. & Chua, T.-S. Graph-refined convolutional network for multimedia recommendation with implicit feedback. In Proceedings of the 28th ACM International Conference on Multimedia 3541–3549 (2020).

Li, X. et al. Hierarchical fashion graph network for personalized outfit recommendation. In Proceedings of the 43rd International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval 159–168 (2020).

Liu, K., Xue, F., Li, S., Sang, S. & Hong, R. Multimodal hierarchical graph collaborative filtering for multimedia-based recommendation. IEEE Trans. Comput. Soc. Syst. 11, 216–227 (2022).

Tao, Z. et al. Mgat: Multimodal graph attention network for recommendation. Inf. Process. Manag. 57, 102277 (2020).

Cui, Z., Yu, F., Wu, S., Liu, Q. & Wang, L. Disentangled item representation for recommender systems. ACM Trans. Intell. Syst. Technol. 12, 1–20 (2021).

McAuley, J., Targett, C., Shi, Q. & Van Den Hengel, A. Image-based recommendations on styles and substitutes. In Proceedings of the 38th International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval 43–52 (2015).

Kipf, T. N. & Welling, M. Semi-supervised classification with graph convolutional networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:1609.02907 (2016).

Zhang, M. & Chen, Y. Link prediction based on graph neural networks. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst.31 (2018).

Yu, X., Xu, W., Cui, Z., Wu, S. & Wang, L. Graph-based hierarchical relevance matching signals for ad-hoc retrieval. In Proceedings of the Web Conference 778–787 (2021).

Franceschi, L., Niepert, M., Pontil, M. & He, X. Learning discrete structures for graph neural networks. In International Conference on Machine Learning 1972–1982 (PMLR, 2019).

Chen, Y., Wu, L. & Zaki, M. Iterative deep graph learning for graph neural networks: Better and robust node embeddings. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 33, 19314–19326 (2020).

Luo, D. et al. Learning to drop: Robust graph neural network via topological denoising. In Proceedings of the 14th ACM International Conference on Web Search and Data Mining 779–787 (2021).

Jin, W. et al. Graph structure learning for robust graph neural networks. In Proceedings of the 26th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining 66–74 (2020).

Zhu, Y. et al. Deep graph structure learning for robust representations: A survey, Vol. 14, 1–1. arXiv preprint arXiv:2103.03036 (2021).

Chen, L. et al. Enhancing multi-modal perception and interaction: An augmented reality visualization system for complex decision making. Systems 12, 7 (2023).

Li, A., Yang, B., Huo, H., Hussain, F. K. & Xu, G. Structure-and logic-aware heterogeneous graph learning for recommendation. In 2024 IEEE 40th International Conference on Data Engineering (ICDE), 544–556 (IEEE, 2024).

Zhu, X. et al. Recommender systems meet large language model agents: A survey. Available at SSRN 5062105 (2024).

Tao, Z. et al. Self-supervised learning for multimedia recommendation. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 25, 5107–5116 (2022).

Raj, S., Mondal, P., Chakder, D., Saha, S. & Onoe, N. A multi-modal multi-task based approach for movie recommendation. In 2023 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN), 1–8 (IEEE, 2023).

Li, R., Wang, S., Zhu, F. & Huang, J. Adaptive graph convolutional neural networks. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Vol. 32 (2018).

Wang, X. et al. Am-gcn: Adaptive multi-channel graph convolutional networks. In Proceedings of the 26th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining 1243–1253 (2020).

He, X. et al. Lightgcn: Simplifying and powering graph convolution network for recommendation. In Proceedings of the 43rd International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval 639–648 (2020).

Rendle, S., Freudenthaler, C., Gantner, Z. & Schmidt-Thieme, L. Bpr: Bayesian personalized ranking from implicit feedback. arXiv preprint arXiv:1205.2618 (2012).

Paszke, A. et al. Pytorch: An imperative style, high-performance deep learning library. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Vol. 32 (2019).

Kingma, D. P. & Ba, J. Adam: A method for stochastic optimization. arXiv preprint arXiv:1412.6980 (2014).

Glorot, X. & Bengio, Y. Understanding the difficulty of training deep feedforward neural networks. In Proceedings of the Thirteenth International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics 249–256 (JMLR Workshop and Conference Proceedings, 2010).

Zhou, X. et al. Bootstrap latent representations for multi-modal recommendation. In Proceedings of the ACM Web Conference, Vol. 2023, 845–854 (2023).

Wang, J., Wang, J., Jin, D. & Chang, X. Hypergraph collaborative filtering with adaptive augmentation of graph data for recommendation. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. https://doi.org/10.1109/TKDE.2025.3539769 (2025).

Funding

Funding was provided by PMRF.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Subham Raj conceived the idea and performed the experiments. Sriparna Saha analyzed the results. Subham Raj wrote the manuscripts with valuable input from Sriparna Saha. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Raj, S., Saha, S. Unlocking latent features of users and items: empowering multi-modal recommendation systems. Sci Rep 15, 26309 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-95872-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-95872-4