Abstract

Traits are patterns of brain signals and behaviors that are stable over time but differ across individuals, whereas states are phasic patterns that vary over time, are influenced by the environment, yet oscillate around the traits. The quality of a social interaction depends on the traits and states of the interacting agents. However, it remains unclear how to decipher both traits and states from the same set of brain signals. To explore the hidden neural traits and states in relation to the behavioral ones during social interactions, we developed a pipeline to extract latent dimensions of the brain from electroencephalogram (EEG) data collected during a team flow task. Our pipeline involved two stages of dimensionality reduction: non-negative matrix factorization (NMF), followed by linear discriminant analysis (LDA). This pipeline resulted in an interpretable, seven-dimensional EEG latent space that revealed a trait to state (trait-state) hierarchical structure, with macro-segregation capturing neural traits and micro-segregation capturing neural states. Out of the seven latent dimensions, we found three that significantly contributed to variations across individuals and task states. Using representational similarity analysis, we mapped the EEG latent space to a skill-cognition space, establishing a connection between hidden neural signatures and social interaction behaviors. Our method demonstrates the feasibility of representing both traits and states within a single model that correlates with changes in social behavior.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Neuroscientists have been studying the neural underpinnings of social interactions for decades, aiming to improve social skills, facilitate socialization, and enhance team performance1,2. The neural representations during social interactions depend on two factors: the social context and the innate characteristics of the interacting individuals3,4. The former refers to the individuals’ flexible, context-dependent states, while the latter represents more fixed, inherent traits. For example, consider the interaction between two individuals. Both of their brains might exhibit similar sensitivities in responding to incoming social cues (e.g., gestures, facial expressions, etc.) during an interaction, a stable trait; as a result, they simultaneously experience pleasurable socialization, a temporary state. In contrast, the interaction between individuals with different sensitivities to social cues might result in less pleasurable socialization, another temporary state. Various psychological theories compare traits and states: traits are patterns of the brain signals and behaviors that are stable over time but differ across individuals, whereas states are phasic patterns that vary over time, are influenced by the environment, yet oscillate around the traits5,6,7.

Empirical studies have shown numerous associations between neural activity patterns and traits and states8,9,10. Similar to psychological traits and states, neurologically, brain activities also exhibit trait- and state-like features: the electrophysiological activities across the entire brain form a high-dimensional representation that differentiates among individuals (i.e., a trait-like feature); from time to time, the execution of certain tasks triggers temporal changes to the activities that differentiate among states (i.e., a state like feature). It is important to clarify that the neural traits described in this study using EEG should not be confused with the descriptive personality traits mentioned in the psychology literature (e.g., Big Five personality11,12).

Despite substantial efforts to characterize neural traits or states using brain imaging techniques, particularly electroencephalography (EEG), previous studies have not represented both traits and states in the same model13,14,15,16,17,18. Therefore, a primary goal of the current study is to build an interpretable model to identify a parsimonious set of latent dimensions representing both traits and states in the brain. The second goal is to establish a connection between neural and psychological traits and states – demonstrating that variability in the neural representation of traits and states is associated with behavioral changes across different individuals (traits) and conditions (states). Here, we analyzed a hyperscanning EEG dataset collected in a previous study in which dyadic teams played a music rhythm game—a naturalistic social task—designed to induce three types of states: Team Only, Flow Only, and Team Flow19. Team flow is a unique state of socialization where two (or more) individuals collaborate on tasks with a shared purpose and strong commitment20. It produces exceptionally positive subjective experiences and is thus distinct from individual flow experience or ordinary team interactions, both psychologically and physiologically21.

To achieve our goals and capture the traits and states simultaneously in our team flow dataset, we explored several computational techniques. Principal component analysis (PCA) and non-negative matrix factorization (NMF) are both widely used dimensionality reduction techniques in neuroscience research, capable of extracting low-dimensional and meaningful features from high-dimensional data22,23,24,25,26,27. Support vector machine (SVM) and linear discriminant analysis (LDA) are both classification algorithms and thus suitable for decoding the traits and states28,29,30,31,32. While SVM performs classification using all the input features, LDA was able to apply another layer of dimensionality reduction, which not only facilitates the classification of certain variables but also characterizes meaningful, interpretable latent representations of the data. For example, it has been successfully applied to identify traits of a rich behavior repertoire in mice33,34. Since LDA alone will suffer from the high dimensionality of the features (as we have a limited sample size), we combined it with an additional dimensionality reduction step. Based on our exploration of multiple possible methods (NMF + LDA could achieve the highest out-of-sample classification accuracy of 65.6%, followed by 58.1% with SVM, and 51.1% with PCA + LDA, see details in Supplementary Fig. 1), we decided to move forward with a two-stage dimensionality reduction pipeline utilizing both NMF and LDA.

Using this pipeline, we reduced the whole-brain EEG data from 512 dimensions to a seven-dimensional latent EEG space and identified a trait to state (trait-state) hierarchy. This hierarchy was reflected through the macro- and micro-segregation patterns of the latent space data distribution. Next, we quantified the unique contributions of the latent dimensions (LD) in characterizing inter-individual and inter-state differences in relation to the neural correlates of team flow, and provided visualizations for biological interpretations of the LDs. Finally, we confirmed that the traits and states in the identified latent EEG space shared a similarity structure with a skill-cognition space, thus establishing a brain-behavior association.

Results

An interpretable latent EEG space captured inter-individual and inter-state variabilities

In the current analysis, we utilized the behavioral and EEG data collected in a previous hyperscanning study19. In the study, 15 participants were matched to form 10 pairs (i.e., 5 participants were paired twice) based on their skill level, song preference, and team preference. Each pair of participants then played a music rhythm game in which both players tapped an iPad screen when visual cues (notes) reached a yellow judgment line (Fig. 1A). Participants played under three task conditions: Team Flow, Flow Only, and Team Only. In the Team Flow condition, participants could see their partner’s positive feedback while playing the songs. In the Flow Only condition, team interaction was disrupted by hiding the partner’s positive feedback using an occlusion cardboard between the participants. In the Team Only condition, the flow state was disrupted by scrambling the music. Each team completed 6 songs under each of the three conditions in a pseudorandomized manner for a total of 18 trials (Fig. 1B). After each trial, participants rated their subjective experience on several dimensions, and the ratings were averaged to form the Flow, Team, and Team Flow indices. High-density (128 channels) hyperscanning EEG data were collected from both players while they played the game. The ratings and the EEG data confirmed that the three conditions induced three different states in the participants: compared to the other conditions, participants reported higher Team Flow Index, and exhibited enhanced interbrain synchrony in the Team Flow condition; during the Team Only condition, the Flow Index decreased; and during the Flow Only condition, the Team Index decreased.

Using the EEG data, we built a pipeline to achieve our first goal — identifying latent dimensions that represent inter-individual and inter-state variabilities through each participant’s (i.e., intra-brain) EEG profiles. This pipeline consisted only of linear transformations to enhance model interpretability (Fig. 1C). We started by calculating each participant’s normalized power spectral density (PSD) for each trial over all the 128 EEG channels and 4 frequency bands (i.e., theta: 4–7 Hz, alpha: 8–12 Hz, beta: 13–30 Hz, and low-gamma: 31–50 Hz) as input features (i.e., 512 features), yielding a dataset consisting of 348 trials (i.e., 15 ~ 18 trials per participation, 20 total participations). Next, to avoid overfitting (otherwise the number of features exceeds the number of samples – see Materials and methods for more details), we performed an initial dimensionality reduction using NMF and reduced the dimensions to 160, including the top 40 NMF components from each frequency band. Finally, we conducted LDA on our selected NMF components to form a latent space that maximized the accuracy of classifying each sample’s participation identity (i.e., a single experimental session, if a participant paired twice with different people, that counted as two participations) and task condition (e.g., participant 1’s first participation under Team Only condition). Meanwhile, this LDA model served as a secondary dimensionality reduction, and we determined a final latent space of 7 dimensions based on a knee point detection algorithm. During both stages of dimensionality reduction, the model hyperparameters (i.e., the number of NMF components and the number of LDA latent dimensions) were determined as a trade-off between the model complexity and the final prediction accuracy out of a 5-fold cross-validation (Fig. 2A-C, see details in Materials and methods). Our current choice of features resulted in a validation accuracy of 44.95% (chance level = 1.67%).

To further demonstrate that the ability to classify participations and states is due to the inherent features of our data (i.e., the existence of trait and state characteristics in the EEG profile) instead of an overfitting of noise, we conducted three levels of permutation tests: randomly shuffling the labels of both participation identities and task states, randomly shuffling the task state labels while preserving the participation labels, and randomly shuffling the participation labels while preserving the task state labels. If our classification was an overfitting of noise, we would likely achieve the same level of accuracy even after permuting the labels, indicating no valuable information in the true labels, thus the permutation helped us establish a null distribution of validation accuracy. However, our resulting validation accuracy was significantly higher than all three permutation-based null distributions (shuffle participation and state labels: chance validation accuracy \(\:=\:1.52\%\pm\:0.76\%,\:p<0.001\) ; shuffle state labels only: chance validation accuracy \(\:=\:31.74\%\pm\:2.72,\:\:p<0.001\); shuffle participation labels only: chance validation accuracy \(=1.74\%\pm\:0.82\:,\:p<0.001\); Supplementary Fig. 2).

Because our goal is to better understand the data through a latent representation approach, we next applied our established pipeline to the entire dataset (i.e., 40 NMF components per channel, 7 latent dimensions, without training-validation partition) and examined several properties of this space. Our pipeline generated seven latent dimensions that explained 76.6% between- vs. within-class variance and achieved an in-sample classification accuracy over 99% (Supplementary Fig. 3). We visualized this latent space by projecting each participant’s trial-level intra-brain EEG data onto the top three LDs (Fig. 2D) and found two levels of clustering: a major clustering (or macro-segregation) of participations (indicated by color) and a minor clustering (or micro-segregation) of task conditions within each participation (indicated by shape).

Data acquisition and analysis pipeline. (A) Illustration of the task. Two participants played the music game as a team, in which they both needed to tap an iPad screen when visual cues (notes) reached the yellow judgment line. In the Team Flow condition, the music was typical, and participants sat adjacent to each other. In the Team Only condition, the music was scrambled. In the Flow Only condition, a cardboard separated the participants so they could not see each other’s feedback. (B) The trial sequence: each pair of participants played 18 trials – six songs (S1-S6) under the three conditions in the pseudorandomized order presented. (C) The two-stage dimensionality reduction pipeline. Preprocessed EEG time series of 128 channels went through power spectral analysis, resulting in the power spectral density (PSD) of each channel in the theta (4–7 Hz), alpha (8–12 Hz), beta (13–30 Hz), and low-gamma (31–50 Hz) frequency bands. Next, for dimensionality reduction, 40 latent components per frequency band (from 128 channels) were identified using non-negative matrix factorization (NMF). Finally, all these NMF components were transformed into a 7-dimensional latent space through linear discriminant analysis (LDA) to maximize the distances between the participation × condition classes.

Latent space representation of the team flow data shows macro- and micro-segregation. (A-C) Feature selection of the two-stage dimensionality reduction. (A) Classification accuracy. Training (left) and testing (right) accuracies on the classification of each participation × condition class. Heatmap shows how the accuracy was affected by the choice of the number of NMF components (horizontal) and LDA latent dimensions (vertical). (B) Selection of NMF components. The number of NMF components to include in the model depends on the area-under-curve (AUC) value of the classification accuracy on the validation set, across 20 LDA latent dimensions. (C) Selection of LDA latent dimensions. The number of LDA latent dimensions to include in the model was decided as the knee point of the accuracy curve. (D) Visualization of the latent space and the macro and micro-segregation model. Representation in the top three latent dimensions. Each scatter represents the data of one trial after the two-stage dimensionality reduction. Color denotes the participation identity, and three shapes correspond to the three task conditions (circle, TF = Team Flow; square, TO = Team Only; triangle, FO = Flow Only). Two representative participations (Part X, Part Y) are zoomed in to show the macro-segregation between the participations and the micro-segregation between the different task conditions in the current 3D latent EEG space.

Macro- and micro-segregation of the latent EEG space correspond to an individual’s traits and states

So far, the intra-brain latent EEG space showed a pattern of macro-segregation across participations (or individuals) and micro-segregation across task conditions (within each participation). We hypothesized that the macro- and micro-segregations represent the neural manifestations of traits and states, respectively, in a trait-state hierarchical structure. More specifically, each participant occupied a locus in the latent space corresponding to the personal traits (i.e., macro-segregation) due to unique EEG characteristics. These characteristics were subject to subtle variations around the loci depending on the external environments (e.g., experimental manipulation), and thus these variations represented an individual’s state (i.e., micro-segregation). However, several alternative possibilities exist. In this section, we tested our hypothesis against these alternatives.

First, we wanted to test whether the macro- and micro-segregations are truly hierarchical. LDA does not guarantee a specific structure of the space, and there can be three possible structures. One possibility is that there is no hierarchy at all – any participation-state cluster can be close to or far from any other cluster (no hierarchy; Fig. 3A). Another possibility is that states constitute macro-segregations, and traits constitute micro-segregations within each state (state-trait hierarchy; Fig. 3B). This is plausible as a previous study has found several neural correlates that showed significant differences between the three task conditions, and within each condition there were smaller variabilities across participants19. The last possibility is our hypothesized model, in which traits form macro-segregations and states form micro-segregations within each trait (trait-state hierarchy; Fig. 3C). In other words, individuals’ EEG profiles differ largely from each other, and the variations across different task conditions are more subtle.

To distinguish these three possibilities empirically, we derived the inter/intra-individual distance ratio as a testing metric. We first identified the centroids of each data class (i.e., all the samples that share the same participation and task state label) in the 7-dimensional latent space. Then, we defined the inter-individual distance as the Euclidean distance between any two data classes from a same task state but different participations, and the intra-individual distance as the Euclidean distance between any two data classes from a same participation but different task states. In the case of state-trait hierarchy, intra-individual distances should be larger than inter-individual distances, so the ratio should be smaller than 1. In the case of no hierarchy, the inter/intra individual distance ratio should be equal to 1. Similarly, in the case of trait-state hierarchy, that ratio should be greater than 1. The actual inter/intra-individual distance ratio from the data was 7.08, and was significantly greater than the null distribution (null distribution:\(\:M=\:1.00,\:SD=0.048,\:\:p\:<\:0.001\); Fig. 3D). These results supported our hypothesis that the trait-state hierarchical structure is valid beyond visual appearance.

Next, while we assumed that the macro-segregations represent traits, a counterargument is that they instead represent features related to experimental setup during each instance of participation. If our hypothesis is correct, samples from the participants who participated twice in the study (labeled as two separate participations in the model) should be located closer to each other in the latent EEG space than samples from entirely different participants, since their innate neural features (i.e., traits) should be relatively stable even during different experiment participations. A one-tailed independent sample t-test showed that the Euclidean distances between two participations of the same individual (\(\:M=2.63,\:SD=0.56)\) are significantly smaller than the distances between any different pairs of individuals (\(\:M=3.74,\:SD=0.90;\:T\:\left(188\right)\:=\:2.75,\:p\:=\:0.007\)). In addition, we performed a hierarchical clustering across participations. Participants were labeled as adjacent if they occur within the first and second linkage steps. We found that 3 out of 5 repeated participations from the same participant were clustered adjacent to each other in the dendrogram (Fig. 3E). These analyses suggest that the macro-segregation represents neural traits rather than random features associated with participation circumstances.

Thus far, we have successfully excluded several alternative possibilities. All the above analyses supported our trait-state hierarchy hypothesis, that the latent EEG space represents individual neural traits in the form of macro-segregations at a higher hierarchy, as well as neural correlates of the task states in the form of micro-segregations at a lower hierarchy.

Hypothetical models of the intra-brain latent space hierarchy. (A) No hierarchy model. Inter- and intra-individual distances are of the same magnitude. (B) State-trait hierarchy model. Macro-segregation represents state, and micro-segregation represents trait. Inter-individual distance is smaller than intra-individual distance. (C) Trait-state hierarchy model. Macro-segregation represents trait, and micro-segregation represents state. Inter-individual distance is greater than intra-individual distance. (D) Quantification of segregation. The inter-individual distance is larger than the intra-individual distance, and their difference is significantly above chance. The vertical line is the inter/intra-individual distance ratio from the actual data, and the histogram shows the null distribution, calculated through 5000 permutations (i.e., shuffle the subject and task labels). (E) Hierarchical clustering of task participations. Subject task participations are clustered based on their average latent EEG distance. Subjects who participated twice are highlighted. The repeated participations are clustered closer to each other, indicating subject-specific, trait-like characteristics of the latent EEG dimension.

Contributions of latent dimensions to inter-individual and inter-state differences

We next investigated the contribution of each latent dimension to the characterization of trait and state variabilities; that is, which latent dimensions captured differences across individuals, and which latent dimensions captured differences across the three task states.

To identify LDs that captured inter-individual differences, we utilized the repeated participations in the dataset. We defined a repeated vs. non-repeated participation distance ratio to quantify the distance between the repeated participations of the same individual relative to the distance between any two different individuals. If an LD captures inter-individual differences, it should feature a larger non-repeated participation distance and a smaller repeated participation distance, thus the ratio is small. Among the seven LDs, LD1 (\(\:M=0.732,SD=1.217,T\left(1923\right)=8.256,p<0.001)\), LD3 (\(\:M=0.895,SD=1.593,T\left(1923\right)=6.296,p<0.001\)), and LD5 (\(\:M=1.158,SD=1.541,T\left(1923\right)=3.808,p=0.001\)) had significantly smaller repeated vs. non-repeated participation distance ratios compared to a bootstrapped null distribution (\(\:M=1.552,SD=2.784\)), indicating their contribution to the characterization of individual traits (Fig. 4A).

To identify LDs that captured inter-state differences, we first normalized the LDs within each trial, and then performed one-way ANOVA across three conditions for each LD (Fig. 4B). A significant main effect of condition was found in LD1 (\(\:F\left(\text{2,345}\right)=16.40,p<0.001\)), LD3 (\(\:F\left(\text{2,345}\right)=6.03,p=0.019\)), and LD5 (\(\:F\left(\text{2,345}\right)=7.42,p=0.005,\) all p values after Bonferroni correction). Post hoc pairwise Tukey tests showed that in LD1, all three conditions were significantly different from each other (\(\:{M}_{TF}=-1.60,\:{SD}_{TF}=4.73\:;\)\(\:{M}_{TO}=-0.12,\:{SD}_{TO}=4.87;\)\(\:{M}_{FO}=1.72,\:{SD}_{FO}=3.57;\)\(\:TF\:vs.\:\:TO:p=0.029,TF\:vs.\:FO:p=0.004,\:\:TO\:vs.\:FO:\:p<0.001\)). In LD3, Team Flow (\(\:{M}_{TF}=1.04,\:{SD}_{TF}=4.76)\) was significantly different from the other two conditions\(\:\:(TF\:vs.\:TO:p=0.015,\:TF\:vs.\:FO:p=0.004)\), whereas there was no significant difference between the Team Only (\(\:{M}_{TO}=-0.41,\:{SD}_{TO}=3.28\:)\) and Flow Only condition\(\:\:({M}_{FO}=-0.63,\:{SD}_{TO}=3.05\:)\). In LD5, Flow Only (\(\:{M}_{FO}=-0.91,\:{SD}_{TO}=3.42\:)\) was significantly different from the other two conditions (\(\:FO\:vs.\:TF:\:p<0.001,\:FO\:vs.\:TO:p=0.038)\) and the difference between the Team Flow \(\:\left({M}_{TF}=0.75,\:{SD}_{TF}=2.61\right)\:\)and Team Only condition \(\:\left({M}_{TO}=0.16,\:{SD}_{TO}=2.16\right)\:\)was not significant. Note that the sign of the LD values is not meaningful; thus we only focus on the statistical difference between the conditions. The above results suggested that LD1 is associated with a task component that differs across all conditions, LD3 is a unique neural correlate of the team flow state, and LD5 is a unique neural correlate of a team (vs. no-team) state.

Latent dimensions capture inter-individual and inter-condition differences. (A) Inter-individual differences. Within repeated participation distance refers to the Euclidean distance between the two repetitions of one individual participant, between non-repeated participation distance refers to the Euclidean distance between any different participants. Boxplots show the distribution of the ratio between the within repeated participation distance and between non-repeated participation distance for each LD (in ascending order). The horizontal line shows the chance level. The ratio is significantly below the chance level for LD1, LD3, and LD5, suggesting that these latent dimensions contribute to the characterization of inter-individual differences. (B). Inter-condition differences. The latent dimension scores across three task conditions: Team Flow, Flow Only, and Team Only. LD scores were mean centered across conditions within each song. The horizontal line within each box represents the median, and the triangle represents the mean. Significant differences were found among conditions in LD1, LD3, and LD5 using ANOVA. Asterisks denote significant post hoc pairwise comparisons. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Latent dimensions were formed by distributed brain networks

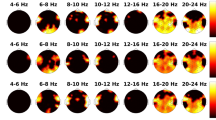

To understand the biological meaning of the latent dimensions, especially LD1, LD3, and LD5, which contributed the most to the inter-individual (trait) and inter-state differences, we traced the primary components contributing to them derived from the non-negative matrix factorization. Primary components of an LD were defined as components whose weights (on the LD) exceeded three times standard deviation over the average (i.e., as an empirical rule for selecting top 0.15% of the results) across all 160 NMF components. Based on this criterion, seven beta NMF components and two low-gamma NMF components were considered as primary components (Fig. 5A): LD1 was characterized by Beta NMF 1, Beta NMF 8, Gamma NMF 3, and Gamma NMF 30; LD3 was characterized by Beta NMF 2, Beta NMF 3, and Gamma NMF 3; LD5 was characterized by Beta NMF 1 and Beta NMF 11. Since we knew the linear transformation between NMF components and power spectral density channels, we further traced the contribution of each PSD channel in building up the primary NMF components (Fig. 5B).

Alternatively, we could map each LD directly to the PSD channels by multiplying two weight matrices: a weight matrix from LD to NMF components (Supplementary Fig. 4), and a weight matrix from NMF components to PSD channels (Supplementary Fig. 5–11, column 1). We also highlighted the differences among the 3 task states for each LD by multiplying the LD to PSD map with the normalized PSD topographic map of each task state (Supplementary Fig. 5–11, columns 2–4).

In both approaches, we found that PSD from the beta and low-gamma frequency bands contained more valuable information than the theta and alpha frequency bands. However, within these frequency bands, we did not find a single brain region as the primary contributor to any LD. Instead, each LD was a weighted combination of many channels that were distributed across all the brain lobes, forming diverse network patterns.

Two-stage tracing of the major contributing EEG channels to the latent dimensions. (A) The projection matrix from LD to NMF components. Primary NMF components whose weights in the projection matrix exceed 3 standard deviations above/below the mean are highlighted. Only beta and low-gamma frequency bands are shown, as there are no primary NMF components in the theta and alpha frequency bands. LD1 mainly consisted of beta NMF 1, beta NMF 8, low-gamma NMF 3, and low-gamma NMF 30; LD3 mainly consisted of beta NMF 2, beta NMF 3, and low-gamma NMF 3; LD5 mainly consisted of beta NMF 1, and beta NMF 11. (B) The topographical map showing the weight of all 128 PSD channels on the primary NMF components. LD: latent dimension from the linear discriminant analysis, NMF: non-negative matrix factorization, PSD: power spectral density.

The latent EEG space shares a representational similarity pattern with a skill-cognition space

Finally, having understood the trait-state hierarchical structure of the latent space, we wondered whether the latent EEG traits and states were biologically meaningful – if they represent the functional differences of the brain (across individuals and across task conditions) instead of the brain anatomy alone, they should have some associations with behaviors. To address this question, we utilized representational similarity analysis (RSA) – a technique that helps establish connections between different spaces through their shared similarity structure35. Given the nature of the task, we constructed a skill-cognition space using seven behavioral trait- and state-based measures: skill level (or performance), Flow Index, Team Index, song preference, and condition preference for each of the three conditions (see details in Materials and methods). Based on the Euclidean distance between pairs of samples in the skill-cognition space, we built a skill-cognition representational dissimilarity matrix (RDM) across all the experimental trials (Fig. 6A). Similarly, we built a neural RDM from the latent EEG space (Fig. 6B). We then assessed the correlation between the neural RDM and skill-cognition RDM, and found a significant correlation between them \((Pearson{\prime\:}s\:r\:=0.273,\:p<0.001\), corrected with permutation test), suggesting a shared similarity structure between the latent EEG space and skill-cognition space (Fig. 6C-D, note that the association was also significant after excluding dissimilarities from different trials of the same participant, see Supplementary Fig. 12). In other words, if the neural characteristics of one individual during one trial were similar to those during another trial (either from the same individual or from a different individual), then the team flow experience would be similar between the two trials.

Latent neural space shares a similarity pattern with a skill-cognition space. Representational dissimilarity matrices (RDMs) were built in (A) a skill-cognition space and (B) a latent EEG space across all trials. Each cell represents the Euclidean distance between two trials. Trials from the same participation (i.e., one participant’s one experimental session) are placed together, as indicated by participation labels 1–20. (C) Correlations between the RDMs in the two spaces. Data from the same participant are highlighted in light green. Numbers indicate Pearson’s correlation and uncorrected p-value. (D) Permutation test of the RSA significance by calculating the correlation between RDMs 5000 times after randomizing the column and row orders of the latent EEG RDM. A red line indicates the actual correlation, and the histogram indicates the distribution of correlations from the permutations. Numbers indicate the corrected p-values.

Discussion

Our analysis pipeline offers several advantages over existing approaches: (1) it identifies both traits and states within a single neural latent space, (2) it provides evidence for a trait-state hierarchy in the neural space, (3) it maintains neurobiological interpretability, and (4) it correlates with a non-neural skill-cognition space that captures social interactions. However, our analysis has some limitations, including a small sample size, limited behavioral measurements, and restricted spatial resolution.

The first advantage of our identified latent space is its ability to classify individuals (traits) and task conditions (states) simultaneously in a unified framework. To our knowledge, existing EEG studies have only considered one aspect. Many EEG studies have investigated human neural states and built predictive models to classify certain states and cognitive processes, such as sleep stages13, emotions14, and concentration15. These studies focused on the generalizability of the models to predict the states (i.e., experimental conditions) without accounting for individual differences. Conversely, other studies focused solely on classifying or recognizing the identity of individuals based on EEG metrics – a technique known as ‘EEG fingerprinting’16,17,18. These fingerprinting studies did not account for different states within each individual. Therefore, to our knowledge, this is the first EEG-based framework to model both traits and states in a single EEG latent space.

Second, our analysis pipeline provided empirical results for a trait-state dichotomy in the neural space, contributing new insights to existing psychological theories. Conceptually, traits systematically differ across individuals and remain stable across situations, while states vary within individuals depending on specific situations and moments in time. Mathematically, according to the whole trait theory, traits are density distributions of momentary states, and states oscillate around traits6,36. Our current findings revealed a novel hierarchical feature on top of the trait and state dichotomy. In our EEG latent space, we observed macro-segregations consisting of all the data from each participation, representing unique ‘trait’ clusters at a higher hierarchy, as well as micro-segregations consisting of the data from each task condition within the trait clusters, suggesting smaller ‘state’ clusters that deviate from the center of their trait clusters. In the current dataset, a subset of participants participated twice in separate sessions; the finding that neural distances from repeated participations of the same participant were closer than those from different participants further emphasized the existence of trait-like features in the neural signals.

These findings highlight the importance of modeling individual differences when studying neural correlates of cognitive processes. Traditional approaches average EEG activity across participants under each task condition, treating individual differences as noise. In contrast, our results suggest that individual differences are a crucial component, as the same experimental manipulation may produce different effects across individuals. This trait-state hierarchy offers a valuable framework for future research in cognitive neuroscience.

Third, our pipeline preserves neurobiological interpretability. Existing EEG fingerprinting studies often prioritize algorithm performance, leveraging high-dimensional spaces and non-linear transformations at the cost of interpretability. In contrast, our approach goes beyond achieving classification goals by examining the contribution of each latent dimension (LD) to traits and states. Among the seven LDs, three (LD1, LD3, LD5) significantly explained variations in both individual traits and task states. LD1 differentiated all three states, LD3 separated team flow states from non-team flow states, and LD5 distinguished team states from non-team states. These results highlight how latent dimensions can reveal compound neural patterns that collaboratively distinguish traits and states, offering a data-driven perspective beyond traditional single-channel analyses.

Using linear transformations, we recovered the EEG channel weights for each LD and visualized their contributions. Consistent with prior findings19, beta and low-gamma frequency bands were more influential in the team flow task compared to alpha and theta bands. While several temporal lobe channels (e.g., NMF Beta 3, NMF Beta 8) aligned with previous studies, we found that the neural correlates of the LDs were widely distributed across the brain, including frontal, parietal, and occipital lobes. This supports the view of the brain as a distributed network system, where baseline network organization predicts traits10,37 and co-activation patterns predict task states38. Social interaction engages multiple brain networks, including the salience, default mode, central executive, and subcortical networks39. However, as existing evidence primarily comes from fMRI and PET studies, further research is needed to explore how our EEG-based findings translate into these broader contexts.

It is important to note that the macro-segregation may arise from various factors: it could reflect individual anatomical differences, such as brain volume, bone thickness, and 3D blood networks40,41,42; functional differences, such as resting-state activity and its coherence network that establishes the baseline for neural information processing43; or task-specific brain functions, such as responsiveness to musical rhythm. Using representational similarity analysis, we demonstrated a shared representation between the EEG latent space and a skill-cognition space, constructed from subjective surveys and performance data related to team flow during the task. This shared representation suggests that the latent EEG dimensions are predictive of the team flow experience. For example, if the EEG characteristics of an ongoing trial resemble those from a previous trial with high team flow, the participant is likely to experience high team flow again. Similarly, participants with closer proximity in the EEG space tend to report similar team flow experiences. These findings indicate that the macro-segregation in the latent space reflects functional differences relevant to social cognition and is not solely the result of anatomical differences.

In addition to its advantages, our study has several limitations. First, the sample size was constrained by COVID-19 restrictions during the experiment and the subsequent unavailability of professional players, which limited our ability to collect additional data. Larger datasets are needed to validate the robustness of our pipeline and findings across a broader range of participants and task types. Second, the number of available behavioral measures was limited. While we observed a close mapping between the latent EEG space and the skill-cognition space, the possibility remains that the latent EEG dimensions may correlate with other behavioral measures. Future research should incorporate more comprehensive behavioral assessments to explore additional neural-behavioral associations. Lastly, our analysis relied on the power spectral density of surface EEG channels, which offers limited spatial resolution. To improve the interpretation of latent dimensions, future studies could utilize alternative imaging modalities or EEG source localization techniques to achieve higher spatial precision.

Conclusion

Using a two-stage dimensionality reduction pipeline combining non-negative matrix factorization and linear discriminant analysis, we extracted a seven-dimensional latent EEG space from the whole-brain power spectrum. This space revealed a hierarchical trait-state structure in the neural data, where individual participants formed primary clusters at a higher level, and task states within each participant formed sub-clusters. A subset of latent dimensions (LD1, LD3, LD5) significantly contributed to inter-individual and inter-state differences and could be traced back linearly to their primary EEG channels. Trial-to-trial similarities in this latent neural space mirrored those in a skill-cognition space.

Our approach and findings have potential applications in broader contexts, including latent trait-state identification across different task contexts, dynamic trait-state-based team pairing, and predictive modeling of team behaviors.

Materials and methods

Data source

We conducted all analyses on a published team flow dataset19. In the study, 15 participants (5 males; age: 18–35 years) played a music rhythm game in 10 pairs (3 male pairs), among which 5 participants (1 male) were paired twice. We defined a participation as a single experimental session for one participant, resulting in a total of 20 participations. Participants were screened and matched to pairs according to their skill level and song preference. During the task, while listening to a song, participants tapped a touch screen when the animated visual cues reached a designated area, and received instantaneous positive feedback. The task consisted of three interleaved conditions: Team Flow (TF), Team Only (TO), and Flow Only (FO). Each condition contained 6 trials (1 song per trial). At the end of each trial, participants answered nine rating questions about their task experience, including their skill-demand balance (Q1 “I had the necessary skill to play this trial successfully” and Q2 “I will enjoy this trial more if it has less/more notes”), feeling in control (Q3 “I felt in control while playing this trial”), automaticity (Q4 “I made correct movements automatically without thinking”), enjoyment (Q5 “I love the feeling of this trial and want to play it again”), time perception (Q6 “How time flies during this trial”), awareness of partner (Q7 “I was aware of the other player’s actions”), teamwork (Q8 “I felt like I was playing with the other person as a team”), and coordination (Q9 “I was coordinating my fingers with the other player’s fingers”). Ratings on Q1-Q6 were averaged as an index of individual flow (Flow Index), and the ratings of Q7-Q9 were averaged as an index of team interaction (Team Index). The Team Flow Index was the average of Team Index and Flow Index. Results from the ratings showed that Team Flow induced more positive emotions, including enjoyment (more details can be found in the Extended Fig. 2 − 1 from Shehata et al.19). The final dataset included 18 trials in total under three different task conditions. During the task, the EEG data of both players were collected simultaneously. Data were obtained with permission from Shehata et al.19. More details about their data collection and processing can be found in their previous publication19.

EEG analysis

To analyze the neural correlates (NC) of game play experience, EEG data were epoched at 3s intervals. EEG data were bandpass filtered at 0.5–50 Hz, using the Parks-McClellan FIR filter, and re-referenced to the average of all channels. After this initial preprocessing, we did a visual inspection for artifacts, including EMG, then performed artifact rejection using automatic independent component analysis (ICA) rejection in the FASTER toolbox44. Bad channels showing line noise noted during recording sessions were rejected and interpolated during the FASTER preprocessing. For more details, please refer to Shehata et al.19.

Power spectral density

Power spectral density (PSD) was estimated using Welch’s overlapped segment averaging estimator. The PSD was first calculated for all the epochs (varied between 20 and 25) and then averaged within each trial, resulting in trial-wise PSD at each of the 128 channels. For each channel, the PSD was then averaged within delta (1–3 Hz), theta (4–7 Hz), alpha (8–12 Hz), beta (13–30 Hz), and low-gamma (31–50 Hz) frequency bands. This analysis was conducted using the EEGLAB toolbox45,46 in MATLAB 2016a with default parameters, in the same way described in the previous publication19.

Two-stage dimensionality reduction and latent space identification

To identify a latent EEG space that characterizes variability both across individuals and across task states, we conducted a two-stage dimensionality reduction on the PSD data, utilizing non-negative matrix factorization (NMF) and linear discriminant analysis (LDA).

In the first stage NMF dimensionality reduction, the input samples were participants’ trial-wise data (total N = 348), and the features were the PSD of all 128 EEG channels across 4 frequency bands (theta, alpha, beta, low-gamma, d = 128*4 = 512). The goal of NMF was to reduce redundant information in the dataset and avoid overfitting during LDA (otherwise, the feature dimension would exceed the sample size, in which case executing the LDA algorithm would be impossible). We normalized all the input data as follows: for each feature, we first normalized all three trials within each song (e.g., S1 TF, S1 FO, S1 TO) by subtracting the average PSD across these trials, in order to reduce the systematic noise due to song differences; next, we added the average PSD within each participation to their corresponding normalized trials to retain subject-specific PSD information in the data. To facilitate the interpretation of NMF components, we conducted NMF for each frequency band separately. During each NMF, the original data matrix V (348*128) was factorized into two non-negative matrices, a feature matrix W (348*p) and a coefficient matrix H (p*128), so that the multiplication of W and H could approximately reconstruct V. Here, p represents the number of NMF components/new features, each column in W is a new feature, and each column in H represents the coefficients/weights of the new features to construct the original sample.

Next, we applied LDA to the output NMF components, including the top 40 NMF components for each frequency band (i.e., p = 40 in each NMF model) as the new feature set. LDA is a supervised learning algorithm used for classification and dimensionality reduction47. It generates a set of latent dimensions (LD) through a linear combination of raw features. These latent dimensions maximize the separability of different classes by increasing the between-class distance and decreasing the within-class distance47. In our case, a class consisted of samples from one of the three conditions in one participant’s one participation (e.g., participant 1’s Team Flow trials when paired with participant 2, 5 or 6 trials in total). Participants who played twice with different partners were counted as two participations. The ‘KFDA’ Python package was used to perform LDA48.

Determination of the number of dimensions

In our pipeline, there were two hyperparameters to decide: the number of NMF components (nNMF) from each frequency band that fed into the LDA, and the final number of LDs (nLD) as the output. To make these decisions, we performed 5-fold cross-validation (repeated 100 times) and used the average validation accuracy as an objective criterion. Our goal was to find a trade-off between the dimensionalities and the generalizability of the classification algorithm. We repeated the cross-validation using different combinations of nNMF and nLD, with nNMF ranging from 10 to 70 (step size = 5), and nLD ranging from 1 to 20 (step size = 1), resulting in two accuracy heatmaps (Fig. 2A). For each NMF component, we calculated the area-under-curve (AUC) of the validation accuracy over all the LDs (Fig. 2B). Note that the AUC here does not mean the AUC of an ROC curve, but represents an averaged accuracy across different choices of nLD, so its value can exceed 1. Because the accuracy AUC monotonically increased with the increase of nNMF, we chose a local maximum of 40 as a balance point instead of the global maximum of 70. After deciding on the nNMF, we examined how the corresponding validation accuracy (with the choice of nNMF = 40) changed with the increase of nLD (Fig. 2C). As it also increased monotonically but in a concave shape, we calculated the location of a knee (or elbow) point on this curve, at which the increase in accuracy along the nLD was no longer rapid (i.e., the benefit of including one more LD diminished). This nLD was found to be 7. The knee point detection was conducted using the ‘kneed’ package in Python49.

Control analysis of the LDA classification performance

To rule out the possibility that the data clustering pattern in the latent space resulting from LDA is an overfitting of noise, we conducted three types of permutation test: (1) randomly shuffling both the participation and task condition labels, (2) randomly shuffling the task condition labels while keeping the participation labels the same, and (3) randomly shuffling the participation labels while keeping the task condition labels the same. For each type of permutation, we repeated the same procedure as in the initial identification of the latent space – we selected the top 40 NMF components per frequency band, and conducted LDA with 5-fold cross-validations to assess the average training and validation accuracy. Each permutation was repeated 500 times, such that the distribution of the validation accuracy served as a null distribution and was further compared with the validation accuracy of the original dataset (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Confirmatory analyses for the macro- and micro-segregation model

Test of the latent space architecture

Our goal was to test among three alternative hypotheses about the hierarchical structure of the latent EEG space: (1) state-trait hierarchy, (2) trait-state hierarchy, and (3) no hierarchy. To achieve this goal, we defined inter-individual distances and intra-individual distances. We first calculated the centroid (i.e., the average 7D coordinates of all the trial samples) of each task condition from each participation/individual. Then we defined an inter-individual (or intra-state) distance as the Euclidean distance between the centroids of two participations/individuals with the same task condition (i.e., PxSa – PySa), and an intra-individual (or inter-state) distance as the Euclidean distance between two task conditions for the same participation/individual (i.e., PxSa – PxSb; Fig. 3A-C). The inter/intra-individual distance ratio was calculated as the mean inter-individual distance divided by the mean intra-individual distance. We also constructed a null distribution of the inter/intra-individual distance ratio by performing the calculations over 5000 random permutations of participation and task condition labels. Finally, we compared the inter/intra-individual distance ratio to the null distribution: if the actual distance ratio is not significantly different from the null distribution, there is no hierarchy in the data; if the actual distance ratio is significantly above the null distribution, there is a trait-state hierarchy; and if the actual distance ratio is significantly below the null distribution, there is a state-trait hierarchy. We calculated the p-value as the percentile of the actual distance ratio on the null distribution of the distance ratio.

Hierarchical clustering

We performed a hierarchical clustering in the latent neural space among all participations of all participants. Euclidean distances between participation centroids (i.e., average 7D coordinates of all the trial samples within a participation) were calculated. Based on these distances, participations most proximate to each other were paired into binary clusters, and these binary clusters were grouped into larger clusters given the distances between binary clusters (Fig. 3E).

Representational similarity analysis

We tested whether the identified EEG latent space shared a similarity structure with a non-neural, psychological space using representational similarity analysis (RSA). We first constructed a skill-cognition space using seven variables: Flow Index, Team Index, skill level, song preference, and condition preference for each task condition. For both the EEG latent space and the skill-cognition space, we then calculated the Euclidean distance between every pair of trials. These distances served as indices of dissimilarity, producing two dissimilarity matrices (Fig. 4A and B). Next, we calculated Pearson’s correlation between the dissimilarities of EEG latent space and the skill-cognition space and tested the significance of correlation through permutation (Fig. 4C and D). During the permutation test, we shuffled the rows and columns of the skill-cognition dissimilarity matrix and calculated a new correlation coefficient between the two dissimilarity matrices. We repeated this procedure 5000 times, yielding a null distribution of the correlations. We finally obtained a significance level by comparing the actual correlation with the null distribution.

Quantification of the LD contribution to inter-individual and inter-state differences

For inter-individual differences, we derived a measure to quantify the ability of a latent dimension to minimize the distance between the repeated participations of the same individual, while maximizing the distance between different individuals: repeated vs. non-repeated participation distance ratio. For each LD, we calculated all the distances between the centroids of two participations from any repeated participant as a set of within-repeated-participation-distance, as well as all the distances between the centroids of two different participants as a set of between-non-repeated-participation distance. This allowed us to compute a distribution of the ratio between these two metrics. Meanwhile, we performed bootstrapping 1000 times by repeatedly sampling a within-repeated-participation distance (of one LD) and a between-non-repeated-participation distance (of another LD, may or may not be the same as the previous one) to generate a null distribution of the ratio. Finally, we conducted independent sample t-tests between the ratio distribution of every LD and the null distribution to identify LDs that had a ratio significantly smaller than the null distribution. All the reported p-values were after Bonferroni correction of multiple comparisons.

For inter-state differences, we first normalized the data by subtracting the average LD value across three trials within each song, and then performed one-way ANOVA on each LD across the three task states (TF, FO, TO), as well as the Tukey’s post hoc tests between every pair of states. LDs that were significantly different across the three task states were considered to contribute to the characterization of inter-state differences.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. The analysis code used in this study is publicly available at https://github.com/wuqy052/team_flow_latent_trait_state.

References

Porcelli, S. et al. Social brain, social dysfunction and social withdrawal. Neurosci. Biobehav Rev. 97, 10–33 (2019).

Redcay, E. & Schilbach, L. Using second-person neuroscience to elucidate the mechanisms of social interaction. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 20, 495–505 (2019).

Finn, E. S., Corlett, P. R., Chen, G., Bandettini, P. A. & Constable, R. T. Trait paranoia shapes inter-subject synchrony in brain activity during an ambiguous social narrative. Nat. Commun. 9, 2043 (2018).

Guthrie, T. D., Benadjaoud, Y. Y. & Chavez, R. S. Social relationship strength modulates the similarity of Brain-to-Brain representations of group members. Cereb. Cortex. 32, 2469–2477 (2022).

Steyer, R., Mayer, A., Geiser, C. & Cole, D. A. A theory of States and traits–revised. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 11, 71–98 (2015).

Fleeson, W. & Jayawickreme, E. Whole trait theory. J. Res. Pers. 56, 82–92 (2015).

Tamir, D. I. & Thornton, M. A. Modeling the predictive social Mind. Trends Cogn. Sci. 22, 201–212 (2018).

Haynes, J. D. & Rees, G. Decoding mental States from brain activity in humans. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 7, 523–534 (2006).

Chen, J. et al. Shared and unique brain network features predict cognitive, personality, and mental health scores in the ABCD study. Nat. Commun. 13, 2217 (2022).

Dubois, J., Galdi, P., Paul, L. K. & Adolphs, R. A distributed brain network predicts general intelligence from resting-state human neuroimaging data. Philosophical Trans. Royal Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 373, 20170284 (2018).

Corr, P. J. & Matthews, G. The Cambridge Handbook of Personality Psychology (Cambridge University Press, 2020).

John, O. P. & Robins, R. W. Handbook of Personality, Fourth Edition (Guilford, 2021).

Supratak, A., Dong, H., Wu, C., Guo, Y. & DeepSleepNet: A model for automatic sleep stage scoring based on Raw Single-Channel EEG. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 25, 1998–2008 (2017).

Lin, Y. P. et al. EEG-Based emotion recognition in music listening. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 57, 1798–1806 (2010).

Edla, D. R., Mangalorekar, K., Dhavalikar, G. & Dodia, S. Classification of EEG data for human mental state analysis using random forest classifier. Procedia Comput. Sci. 132, 1523–1532 (2018).

Rosli, F. A., Ardeena, S., Abdullah, A. A. & Salim, M. S. Biometric Authentication System Using EEG Biometric trait – A Reviewin 020135 (Arau, 2021). https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0044955

Jalaly Bidgoly, A., Jalaly Bidgoly, H. & Arezoumand, Z. A survey on methods and challenges in EEG based authentication. Computers Secur. 93, 101788 (2020).

Rashid, M. et al. Current status, challenges, and possible solutions of EEG-Based Brain-Computer interface: A comprehensive review. Front. Neurorobot. 14, 25 (2020).

Shehata, M. et al. Team Flow Is a Unique Brain State Associated with Enhanced Information Integration and Interbrain Synchrony. eNeuro 8, ENEURO.0133-21.2021 (2021).

van den Hout, J. J. J., Davis, O. C. & Weggeman, M. C. D. P. The conceptualization of team flow. J. Psychol. 152, 388–423 (2018).

Pels, F., Kleinert, J. & Mennigen, F. Group flow: A scoping review of definitions, theoretical approaches, measures and findings. PLOS ONE. 13, e0210117 (2018).

Lee, H. & Choi, S. Group Nonnegative Matrix Factorization for EEG Classification. in Proceedings of the Twelfth International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics 320–327PMLR, (2009).

Liu, W., Zheng, N. & Li, X. Nonnegative matrix factorization for EEG signal classification. in Advances in Neural Networks - ISNN 2004 (eds Yin, F. L., Wang, J. & Guo, C.) 470–475 (Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-28648-6_75. (2004).

Rajendra Acharya, U., Sree, V., Alvin, S., Suri, J. S. & A. P. C. & Use of principal component analysis for automatic classification of epileptic EEG activities in wavelet framework. Expert Syst. Appl. 39, 9072–9078 (2012).

Sakai, M. Kernel Nonnegative Matrix Factorization with Constraint Increasing the Discriminability of Two Classes for the EEG Feature Extraction. in International Conference on Signal-Image Technology & Internet-Based Systems 966–970 (2013). (2013). https://doi.org/10.1109/SITIS.2013.156

Subasi, A. Ismail Gursoy, M. EEG signal classification using PCA, ICA, LDA and support vector machines. Expert Syst. Appl. 37, 8659–8666 (2010).

Xu, L., Chavez-Echeagaray, M. E. & Berisha, V. Unsupervised EEG channel selection based on nonnegative matrix factorization. Biomed. Signal Process. Control. 76, 103700 (2022).

Alotaiby, T. N., Alshebeili, S. A., Alotaibi, F. M. & Alrshoud, S. R. Epileptic Seizure Prediction Using CSP and LDA for Scalp EEG Signals. Computational Intelligence and Neuroscience 1240323 (2017). (2017).

Bhardwaj, A., Gupta, A., Jain, P., Rani, A. & Yadav, J. Classification of human emotions from EEG signals using SVM and LDA Classifiers. in 2nd International Conference on Signal Processing and Integrated Networks (SPIN) 180–185 (2015). (2015). https://doi.org/10.1109/SPIN.2015.7095376

Bhattacharyya, S., Khasnobish, A., Chatterjee, S., Konar, A. & Tibarewala, D. N. Performance analysis of LDA, QDA and KNN algorithms in left-right limb movement classification from EEG data. in International Conference on Systems in Medicine and Biology 126–131 (2010). (2010). https://doi.org/10.1109/ICSMB.2010.5735358

Guler, I. & Ubeyli, E. D. Multiclass support vector machines for EEG-Signals classification. IEEE Trans. Inf Technol. Biomed. 11, 117–126 (2007).

Sha’abani, M. N. A. H., Fuad, N., Jamal, N., Ismail, M. F. & kNN and SVM Classification for EEG: A Review. in InECCE 555–565 (Springer, Singapore, 2020). (2019). (eds. Kasruddin Nasir, A. N. et al.) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-2317-5_47

Forkosh, O. et al. Identity domains capture individual differences from across the behavioral repertoire. Nat. Neurosci. 22, 2023–2028 (2019).

Serra, I. et al. Activated PI3Kδ Syndrome, an Immunodeficiency Disorder, Leads to Sensorimotor Deficits Recapitulated in a Murine Model. (2021). https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.01.15.426862 doi:10.1101/2021.01.15.426862.

Kriegeskorte, N., Mur, M. & Bandettini, P. A. Representational similarity analysis - connecting the branches of systems neuroscience. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 4, 1–28 (2008).

Read, S. J. et al. A neural network model of the structure and dynamics of human personality. Psychol. Rev. 117, 61–92 (2010).

Seitzman, B. A. et al. Trait-like variants in human functional brain networks. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 116, 22851–22861 (2019).

Cole, M. W., Bassett, D. S., Power, J. D., Braver, T. S. & Petersen, S. E. Intrinsic and Task-Evoked network architectures of the human brain. Neuron 83, 238–251 (2014).

Feng, C. et al. Common brain networks underlying human social interactions: evidence from large-scale neuroimaging meta-analysis. Neurosci. Biobehavioral Reviews. 126, 289–303 (2021).

Smit, D. J. A., Boomsma, D. I., Schnack, H. G., Pol, H. E. H. & de Geus, E. J. C. Individual differences in EEG spectral power reflect genetic variance in Gray and white matter volumes. Twin Res. Hum. Genet. 15, 384–392 (2012).

Hagemann, D., Hewig, J., Walter, C. & Naumann, E. Skull thickness and magnitude of EEG alpha activity. Clin. Neurophysiol. 119, 1271–1280 (2008).

Fiederer, L. D. J. et al. The role of blood vessels in high-resolution volume conductor head modeling of EEG. NeuroImage 128, 193–208 (2016).

Smit, D. J. A., Stam, C. J., Posthuma, D., Boomsma, D. I. & de Geus, E. J. C. Heritability of small-world networks in the brain: A graph theoretical analysis of resting-state EEG functional connectivity. Hum. Brain Mapp. 29, 1368–1378 (2008).

Nolan, H., Whelan, R. & Reilly, R. B. FASTER: fully automated statistical thresholding for EEG artifact rejection. J. Neurosci. Methods. 192, 152–162 (2010).

Welch, P. The use of fast fourier transform for the Estimation of power spectra: A method based on time averaging over short, modified periodograms. IEEE Trans. Audio Electroacoust. 15, 70–73 (1967).

Brunner, C., Delorme, A. & Makeig, S. Eeglab – an open source matlab toolbox for electrophysiological research. Biomedical Eng. / Biomedizinische Technik. https://doi.org/10.1515/bmt-2013-4182 (2013).

Fisher, R. A. The use of multiple measurements in taxonomic problems. Annals Eugenics. 7, 179–188 (1936).

Nikomborirak, K. Kfda: kernel FDA implementation described in https://arxiv.org/abs/1906.09436

Satopaa, V., Albrecht, J., Irwin, D. & Raghavan, B. Finding a ‘kneedle’ in a haystack: detecting knee points in system behavior. 2011 31st Int. Conf. Distrib. Comput. Syst. Workshops. 166, 171. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICDCSW.2011.20 (2011).

Acknowledgements

This work has been supported by Japan Society for Promotion of Science (JSPS), Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (Fostering Joint International Research(B), Grant Number 18KK0280 for MS and SN. Japan Science and Technology Agency (JST) - Moonshot Research and Development, Grant Number JPMJMS2295-03 for SS and MS. QW was supported by the Caltech NIMH Conte Center (P50MH094258) and Tianqiao and Chrissy Chen Graduate Fellowship, and a grant from the Simons Foundation Autism Initiative to R. Adolphs. We thank Ralph Adolphs and Yue Xu for a helpful discussion and feedback.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

QW, MS, and SS Designed Research; QW and MS Performed Research; QW, MS, SS, and SN Analyzed Data and Wrote the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, Q., Nakauchi, S., Shehata, M. et al. A hierarchical trait and state model for decoding dyadic social interactions. Sci Rep 15, 11399 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-95916-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-95916-9