Abstract

Polyamines are small aliphatic amines whose metabolic reprogramming is involved in the regulation of various plant cellular reactions. Our previous study showed that polyamines increased lignan production in Linum album; however, little is known about the underlying mechanisms. This study aimed to provide more details on how putrescine (Put) regulates lignan biosynthesis in L. album cell culture. Our results showed that Put leads to podophyllotoxin (PTOX) and 6-methoxy podophyllotoxin (6MPTOX) accumulation by increasing the expression levels of phenylalanine ammonia-lyase (PAL) and pinoresinol-lariciresinol reductase (PLR) genes, encoding lignan biosynthesis regulatory enzymes. Put also increased hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) content, while its level decreased in the presence of aminoguanidine (AG) and imidazole, inhibitors of diamine oxidase (DAO) and NADPH oxidase (NOX), respectively. Elevated levels of nitric oxide (NO) and cytosolic free Ca2+ caused by Put treatment were reduced after using inhibitors of nitrate reductase (NR) and nitric oxide synthesis-like (NOS-like) enzymes, as well as Ca2+ influx. Besides, pre-treatment of cells with AG, imidazole, ethylene glycol-bis (β-aminoethyl ether)-N, N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid (EGTA) (Ca2+ chelator), Nɷ-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester (L-NAME), and Sodium tungstate (TUN) (NO generation inhibitors) diminished PAL and PLR transcript levels and PTOX and 6MPTOX accumulation, indicating the involvement of H2O2, NO, and Ca2+ in regulating lignan biosynthesis in L. album cells. Put also stimulated salicylic acid (SA) accumulation, being sensitive to all inhibitors used. Overall, this study suggests that Put-induced H2O2 generation in combination with NO and Ca2+ signals can regulate PAL and PLR genes expression and lignan production, likely in a SA-dependent manner.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Polyamines (PAs), including putrescine (Put), spermidine (Spd), and spermine (Spm) are small nitrogenous and polycationic metabolites that contribute to various plant physiological processes such as embryogenesis, flower development, senescence, and fruit ripening. These compounds also play important roles in plant tolerance to unfavorable conditions as multifunctional agents1. It has been reported that the fluctuations in PAs contents affect the sensitivity of plants to different biotic and abiotic stressors, therefore, their levels need to be strictly controlled2. The accumulation of Put, Spd and Spm during the induction of plant defense responses has been demonstrated in numerous studies3,4,5. In plants, PA biosynthesis begins with the production of Put from arginine (Arg) and ornithine (Orn) through the activity of arginine decarboxylase (ADC) and ornithine decarboxylase (ODC), respectively. This process can be followed by the conversion of Put to Spd by spermidine synthase (SPDS), which is then converted to Spm by spermine synthase (SPMS)6. Furthermore, it has also been revealed that the catabolism of these nitrogenous compounds is involved in the regulation of reactions related to the action of PAs7,8. The degradation of Put in plants is mainly catalyzed by diamine oxidase (DAO), which oxidizes its primary amino groups and produces aldehyde, hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), and ammonium (NH4+). The terminal oxidation and interconversion of Spd and Spm are also catalyzed by polyamine oxidase (PAO), which are accompanied by the production of H2O2 as a by-product7. The H2O2 produced during PA oxidation acts as a signaling molecule that can regulate a wide range of cellular processes in plants, including adaptive reactions9,10. In addition to PA catabolism, NADPH oxidase (NOX), also known as respiratory burst oxidase homologs (RBOH), naturally generates the H2O2 molecule in the plant cell, which can alter the oxidative status in response to various biotic and abiotic stresses11. Some studies have suggested that there is a complex relationship between the oxidation process of PA and the activity of the NOX enzyme, and it appears that they regulate the H2O2-dependent stress signaling pathway by influencing each other12.

PA catabolism may also contribute to the formation of other regulatory molecules such as γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) and nitric oxide (NO)13,14. NO is a gaseous signaling molecule with multiple protective functions that can be rapidly and efficiently synthesized on demand by several potential sources. In addition to the unknown mechanism related to the function of DAO and PAO, two enzymes including nitrate reductase (NR) and nitric oxide synthase-like (NOS-like) also play an important role in the formation of NO in plants14,15. H2O2 and NO are considered as central mediators capable of regulating PA-induced stress responses through interaction with other key regulatory factors14. As a ubiquitous second messenger involved in various plant defense responses, Ca2+ is a possible target for PA-induced signaling pathways. The link between PA catabolism and Ca2+ fluxes in plants has been suggested in several reports8,16. Previous studies have reported that H2O2 and NO derived from PA oxidation can provoke ion conductance by activating specific ion channels, especially Ca2+-permeable channels in the plasma membrane8. Likewise, an increasing number of reports indicate a crosstalk between PA metabolism and phytohormones such as abscisic acid (ABA), ethylene, brassinosteroids, jasmonates, and salicylic acid (SA), which have a meaningful role in plant resistance17. Recently, it has been discussed that SA, as a defense hormone, participates in the regulation of PA biosynthesis pathway. On the other hand, this phytohormone has been found to be essential for the protective function of PAs, including H2O2-dependent stress signaling and transcriptional reprogramming15.

The accumulation of secondary metabolites, especially phenolic compounds, is assumed to be one of the defense responses that can be induced by PA action in various plants18,19. Lignans belong to a sub-group of phenolic compounds that act as an antioxidant barrier against adverse conditions due to their structural characteristics. They also have important biological activities, including antibacterial, antiviral, and anticancer properties20. Earlier works has revealed that PAs, particularly Put, can increase the production of podophyllotoxin (PTOX) and 6-methoxy podophyllotoxin (6MPTOX) as the most important lignans in Linum album Kotschy ex Boiss21,22. However, the underlying mechanism by which PAs induce the biosynthesis of these compounds still needs further investigation. Thus, the aim of this study is to provide more details regarding the regulation of PTOX and 6MPTOX biosynthetic pathway by Put treatment in L. album cells. Accordingly, we attempted to elucidate the possible role of H2O2 derived from Put oxidation in the regulation of PTOX and 6MPTOX production, as well as the expression level of the key biosynthetic genes involved in this pathway in relation to Ca2+, NO, and SA signaling molecules.

Results

Determining the optimal concentration of Put

To determine the optimal Put concentration, L. album cells were treated with 0.1, 0.2 and 0.5 mM Put for 72 h. First, the relative dry weight increase rate (RDIR) of cells was measured in response to different concentrations of Put. The results showed that there was no significant difference between the RDIR of cells treated with 0.1 mM Put and the control, while this factor significantly decreased at 0.2 and 0.5 mM treatments (p ≤ 0.05). The lowest percentage of RDIR was observed in the cells treated with 0.5 mM Put concentration (Fig. 1a).

On the other hand, PTOX and 6MPTOX levels increased significantly in response to 0.1 and 0.2 mM Put, while they showed no change compared to the control sample at 0.5 mM (Fig. 1b, c). Due to the lack of negative effects on the RDIR percentage of the cells, as well as the increase in PTOX and 6MPTOX contents by 47% and 30%, respectively, 0.1 mM Put concentration was chosen as the optimal concentration to pursue the study’s objectives.

The changes in H2O2 content under Put action

Time-varying exposure to exogenous Put (0.1 mM) showed a significant increase in H2O2 content up to 12 h of treatment, and then its value decreased and reached the control level after 24 h. As shown in Fig. 2a, the H2O2 level peaked after 6 h of exposure to Put, which was 2.5 times compared with the control sample. To investigate possible pathways involved in Put-induced H2O2 generation, H2O2 content was then measured in L. album cells pre-treated with DAO and NOX inhibitors (aminoguanidine; AG and imidazole, respectively) after 6 h of Put treatment. The results showed that H2O2 level in the cells pre-treated with both inhibitors decreased relatively and similarly by 28% compared to the cells treated with Put alone. Furthermore, our observations indicated that the use of extracellular Ca2+ chelator (ethylene glycol-bis (β-aminoethyl ether)-N, N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid; EGTA), and NO generation inhibitors (Nɷ-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester; L-NAME and sodium tungstate; TUN) also had a negative impact on Put-induced H2O2 accumulation. Interestingly, pre-treatment of cells with L-NAME reduced the H2O2 content produced via Put by half (Fig. 2b).

The changes in H2O2 content in L. album cells in response to (a) Put treatment over a period of time, and (b) co-treatment of Put with inhibitors EGTA, AG, Imidazole, L-NAME, and TUN after 6 h of exposure. Data are the means of three biological with three technical replicates ± SD. Significant differences (P ≤ 0.05) are shown by different letters.

The fluctuations in NO generation under Put action

The NO content also increased with time during the first 12 h of Put treatment of L. album cells and then decreased to its level in the control sample. The increase in NO level followed a similar trend as changes in H2O2 content and reached its highest value within 6 h after treatment, almost double that of untreated cells (Fig. 3a). To clarify the NO generation source under Put action in L. album cells, the effects of co-application of Put and NO generation inhibitors on its level after 6 h of treatment were checked. The results indicated that L-NAME and TUN caused a 30% and 20% decrease in Put-induced NO generation, respectively. In addition, the effect of H2O2 and Ca2+ signaling pathways on Put-induced NO generation was also analyzed and a decrease in NO content occurred in the cells treated with Put + EGTA, Put + imidazole, and Put + AG (Fig. 3b).

The changes in NO content in L. album cells in response to (a) Put treatment over a period of time, and (b) co-treatment of Put with inhibitors EGTA, AG, Imidazole, L-NAME, and TUN after 6 h of exposure. Data are the means of three biological with three technical replicates ± SD. Significant differences (P ≤ 0.05) are shown by different letters.

Cytosolic free Ca2+ level changes under Put action

The experiment’s results also confirmed that there was a rapid increase in fura-2 AM fluorescence emission intensity in Put-treated L. album cells within 5 min, which was almost 2.5-fold higher than that of control cells. This fluorescence intensity then remained constant for at least 20 min (Fig. 4a). Pharmacological experiments were then performed and the data obtained showed that pre-treatment of cells with EGTA resulted in a strong suppression (45%) of the Put-induced fluorescence emission intensity of fura-2 AM at 5 min after treatment. Similarly, Put + L-NAME treatment also had the same effect on Put-induced enhancement in cytosolic free Ca2+ concentration. Furthermore, use of AG, imidazole, and TUN prior to Put treatment moderately and to a similar extent reduced fluorescence emission compared to those receiving Put alone (Fig. 4b).

The changes in cytosolic free Ca2+ level in L. album cells in response to (a) Put treatment over a period of time, and (b) co-treatment of Put with inhibitors EGTA, AG, Imidazole, L-NAME, and TUN after 5 min of exposure. Data are the means of three biological with three technical replicates ± SD. Significant differences (P ≤ 0.05) are shown by different letters.

SA accumulation induces by Put

The effect of Put on the level of SA phytohormone was also investigated. As shown in Fig. 5a, during Put exposure, there was a gradual increase in SA content as a function of time, from 6 h to 24 h of treatment. Furthermore, Put-induced SA production in L. album cells was differentially sensitive to pre-treatment with the inhibitors EGTA, AG, imidazole, L-NAME and TUN, those that reduced the SA level compared to cells treated with Put alone at 24 h after treatment (Fig. 5b).

The changes in SA content in L. album cells in response to (a) Put treatment over a period of time, and (b) co-treatment of Put with inhibitors EGTA, AG, Imidazole, L-NAME, and TUN after 24 h of exposure. Data are the means of three biological with three technical replicates ± SD. Significant differences (P ≤ 0.05) are shown by different letters.

Changes in endogenous PAs contents in response to exogenous Put

Endogenous PAs levels were measured in response to Put treatment, and HPLC results showed that Put, Spd, and Spm levels increased over time. In fact, the increase in endogenous Put started after 12 h of treatment, and peaked after 48 h with 41% enhancement (Fig. 6a). On the other hand, exogenous use of Put resulted in an increasing trend of Spd and Spm levels between 6 h and 48 h of treatment, with a maximum value at 12 h and 24 h, respectively (Fig. 6b, c). The pharmacological approach obtained after 24 h of treatment revealed that the application of EGTA, imidazole, L-NAME, and TUN before Put treatment result in a partial reduction in endogenous Put level, where reduced level of H2O2 through the use of AG increased its level by 12% compared to Put-exposed cells alone (Fig. 6d).

Effect of Put treatment on the contents of endogenous (a) Put, (b) Spd, and (c) Spm over a period of time in L. album cells. (d) The changes in endogenous Put content in response to co-treatment of Put with inhibitors EGTA, AG, Imidazole, L-NAME, and TUN after 24 h of exposure. Data are the means of three biological with three technical replicates ± SD. Significant differences (P ≤ 0.05) are shown by different letters.

Put up-regulates PAL and PLR genes expression

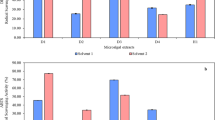

Real-time PCR results pointed out that exposure of cells to 0.1 mM Put up-regulated the expression of phenylalanine ammonia-lyase (PAL) and pinoresinol-lariciresinol reductase (PLR) genes, encoding key regulatory enzymes of lignan production, over a 24-h period. Their expression levels then decreased until 48 h of treatment. The highest transcript levels of these genes occurred after 24 h and were 3.5 and 2.5 times higher than in the untreated state, respectively (Fig. 7a, b). We then examined the underling mechanisms by which Put might affect the expression of these genes. The results revealed that inhibitors of H2O2, NO, and Ca2+ signaling pathways diminished the inducing effect of Put on PAL and PLR genes expression at 24 h after treatment. The highest decrease in the transcripts levels of both genes occurred in the cells treated with Put + L-NAME (Fig. 7c, d).

The changes in relative expression of (a) PAL, and (b) PLR genes in response to Put over a period of time in L. album cells, and the changes in relative expression of (c) PAL, and (d) PLR genes in response to co-treatment of Put with inhibitors EGTA, AG, Imidazole, L-NAME, and TUN after 24 h of exposure. Data are the means of three biological with three technical replicates ± SD. Significant differences (P ≤ 0.05) are shown by different letters.

Put-induced signals increase PTOX and 6MPTOX contents

The effect of Put-induced signaling pathways on lignan production in L. album cells was studied by monitoring the changes in PTOX and 6MPTOX content through pharmacological-based experiments after 72 h of treatment. The results indicated that pre-treatment of cells with EGTA, AG, imidazole, L-NAME, and TUN inhibitors resulted in a significant decrease in PTOX and 6MPTOX levels in comparison with cells treated with Put alone. The biggest change in PTOX content occurred in the Put + EGTA and Put + L-NAME treatments with a decrease of 36%, while in the case of 6MPTOX content, it occurred only in response to Put + L-NAME treatment which was 23% (Fig. 8a, b).

The changes in the contents of (a) PTOX, and (b) 6MPTOX in response to co-treatment of Put with inhibitors EGTA, AG, Imidazole, L-NAME, and TUN after 72 h of exposure in L. album cells. Data are the means of three biological with three technical replicates ± SD. Significant differences (P ≤ 0.05) are shown by different letters.

Discussion

Even with numerous studies on the regulatory role of PA metabolism in plant defense responses under adverse condition23,24, there is still relatively little information on the influence of these small nitrogenous compounds on the modulation of the phytochemical biosynthesis in medicinal plants. Therefore, our study here aims to elucidate the effect of Put catabolism and its possible mechanism of action on the lignan biosynthesis in L. album cells. Similar to the recent study performed on L. album22, it is demonstrated here that Put can increase the production of lignans (PTOX and 6MPTOX) in this plant’s cells. The results also indicated that the enhancement of lignan production is probably carried out by the positive impact of Put on the expression of PAL and PLR genes. These genes have been found to encode the regulatory enzymes of the lignan biosynthesis pathway, and can be targets for various signaling molecules action25,26. Exogenous application of Put also resulted in an increase in H2O2 level during the first hours of treatment. This molecule is known to be an important signaling molecule that mediates various events related to the growth, development and adaptation response of the plants. It is assumed that during the induction of the plant defense system, H2O2 is generated predominantly through the activation of the NOX enzyme11. However, various studies have already suggested that DAO and PAO enzymes can be the alternative sources of H2O2 production in the PA-dependent defense responses7. Our results indicated that co-application of Put with NOX and DAO enzymes inhibitors leads to a partial and equal reduction in the Put-caused H2O2 accumulation, which suggests that this molecule can be generated by the activity of both NOX and DAO enzymes in L. album cells exposed to Put. Based on the results from Put + AG and Put + imidazole treatments, we also found that H2O2 derived from these two enzymatic reactions, likely contributes to the enhancement of PAL and PLR genes expression as well as the lignan production. Therefore, the presented data demonstrate that Put-stimulated lignan biosynthesis in L. album cells can be orchestrated by H2O2 signaling molecule, which originates from the activity of NOX and DAO enzymes. The related function of DAO and NOX enzymes in regulating various plant physiological processes has been previously reported27. It has been suggested that PA production and oxidation may control NOX gene expression and/or enzyme activity, while there is evidence that NOX also plays a role in regulating PA metabolism, which creates a regulatory loop8. The cooperation of these enzymes can lead to precise regulation of H2O2 generation and ensure its proper functioning in various physiological reactions1. Analysis of fluctuations in free PAs contents may provide additional evidence for the collaboration of NOX and DAO enzymes in maintaining H2O2 at a functional level in L. album cells under Put action. It can be assumed that the lack of change in the endogenous Put level during the early hours of treatment is the result of its degradation due to increased activity of DAO, while significant accumulation of Spd and Spm is probably a sign of the positive effect of Put-induced NOX activity on the PA biosynthesis. The subsequent increase in endogenous Put content is likely not only due to the increased decomposition of Spd and Spm, but also to the activation of Put biosynthetic enzymes. It has previously been shown that these enzymes activity and/or genes expression are affected by exogenous Put-induced H2O2 production28. It is interesting that inhibition of NOX activity in Put-treated L. album cells reduced the endogenous Put content, probably due to its increased oxidation to compensate for the reduced H2O2 level27.

In addition to H2O2, PA catabolism also leads to NO accumulation14. The increase in NO level has been detected during the PA action in several plant physiological processes such as stomatal closure12, root growth29, and stress tolerance30. Likewise, Put had an inducing impact on NO generation in L. album cells. The involvement of NO in PA-mediated plant reactions is not far-fetched, as this molecule is an important signaling agent that participates in many physiological functions, including the biosynthesis of the secondary metabolites31,32,33. However, the ways by which PAs can stimulate NO production still need further search. Recent studies have provided genetic and pharmacological evidence for the role of PA oxidation in NO generation12,30. It has been found that two enzymatic sources of NO in plants, including NR and NOS-like enzyme, can be regulated by PA oxidation-derived H2O29. To examine this speculation, we used the inhibitor of DAO enzyme, and the results indicated that H2O2 produced by DAO action can be involved in the Put-induced NO generation in L. album cells. Likewise, our data suggested that NOX-dependent H2O2 production also participates in this process. The suppression of NO generation through inhibiting the activity of NR and NOS-like enzyme also revealed that both enzymatic reactions can lead to an increase in NO level under the regulatory action of Put in L. album cells. It can be also suggested that NOS-like enzyme is perhaps a more important way for NO production in Put-treated L. album cells, since L-NAME has a stronger effect on Put-stimulated NO production. In addition to inducing effect of H2O2 on NO biosynthesis, our results also revealed that an increased level of NO in return can also stimulate H2O2 production. Therefore, Put-induced NO and H2O2 likely act upstream and downstream of each other, creating a signal amplification loop to establish appropriate responses. NO has also been indicated to be related to PA biosynthesis and possibly elevates their levels. The ability of NO to induce the expression of PA biosynthesis genes and inhibit their oxidative enzymes confirms its contribution to PA accumulation, which can subsequently regulate H2O2 homeostasis34. A reduction in endogenous Put content in response to the suppression of the activity of NR and NOS-like enzyme in L. album cells was also consistent with this assumption.

H2O2 and NO signals triggered by PAs can alter genes expression and metabolites production directly or indirectly by stimulating other regulatory agents7. It has been reported that H2O2 accumulation resulting from PA oxidation can increase the cytosolic free Ca2+ level by opening its channels in certain processes such as stomatal closure35 and pollen tubes growth36. As a second messenger, Ca2+ is involved in the induction of the plant defense responses, including the production of secondary metabolites37. Previously, we showed that Ca2+ is a key participant in the signaling cascades leading to the lignan biosynthesis in L. album cells treated with chitosan38. Here, a transient increase in cytosolic free Ca2+ level was also observed in L. album cells in response to Put treatment, which was diminished in the presence of EGTA. These results suggested the potential role of plasma membrane channels in increasing Ca2+ influx and its cytosolic concentration. Further analysis revealed that the H2O2 produced by both NOX and DAO enzymes can be involved in Put-activated Ca2+ influx in L. album cells. In contrast, our results also suggested that Ca2+ flow through plasma membrane channels enhances H2O2 level, which can be due to its positive effect on the activity of NOX and DAO enzymes11,39. In addition, our data obtained from pharmacological assays demonstrated a reciprocal relationship between cytosolic free Ca2+ oscillation and NO generation. It can be assumed that the interrelations among H2O2, NO, and Ca2+ molecules lead to precise regulation of Put-dependent signal transduction network.

Furthermore, there is sufficient evidence for the interaction between PAs and phytohormones in plant physiological processes40. A recent study has confirmed that H2O2-dependent SA production plays a key role in Put-induced defense responses in Arabidopsis thaliana, with about 60% of these responses requiring SA signaling pathway15. Our data consistently showed the positive effect of Put on SA content in a time-dependent manner. Further experiments then presented that Put-provoked H2O2, NO and Ca2+ signals can stimulate SA accumulation independently or in relation to each other. It has been claimed that these molecules can regulate gene expression and the activity of key enzymes involved in the SA biosynthesis pathways41,42. Therefore, it is likely that SA acts as a downstream signaling molecule in transducing the information of other signals to modulate L. album responses to Put.

After characterizing the role of Put oxidation in lignan biosynthesis which was stated at the beginning of the discussion, we also found that H2O2-triggered NO and Ca2+ signaling pathways actively participate in this process. Our results showed that the relative expression of PAL and PLR genes is partially impaired in response to the co-application of Put with NO generation inhibitors and extracellular Ca2+ chelator. Consistent with restriction in the expression of these biosynthetic genes, the inducing effect of Put on PTOX and 6MPTOX contents was similarly reduced in response to these inhibitors. Therefore, it is reasonable to suggest that Put-induced lignan production in L. album cells can be mediated by the interconnections of the signaling molecules triggered by Put oxidation, being able to target and regulate PAL and PLR genes expression.

Conclusion

Overall, our results suggest that Put is able to induce the biosynthesis of lignans by triggering H2O2-dependent signaling cascades in L. album cells (Fig. 9). It was also observed that H2O2 signal comes not only from NOX but also from DAO, underscoring the significant role of Put oxidation in lignan accumulation. Apparently, under the influence of Put, an increase in the H2O2 level is a prerequisite for the induction and amplification of NO production and Ca2+ influx due to NR and NOS-like enzyme stimulation and plasma membrane Ca2+ permeable channels activation, respectively. These signaling molecules have the potential to provoke PAL and PLR genes expression and subsequently PTOX and 6MPTOX production, likely in a SA-dependent manner.

Methods

Cell culture and treatments design

L. album seeds used in this study were obtained from wild-grown plants according to relevant institutional, national, and international guidelines in 2019. The plant collection permit was issued by the Research Ethics Committee of Tarbiat Modares University. The collected plants were identified by Dr. Shahrokh Kazempour-Osaloo, a professor of plant systematics. A voucher specimen of L. album (No. 2450) was deposited in the Herbarium of the Department of Plant Biology of Tarbiat Modares University, Iran. The mature seeds were cultured on solid MS medium and provided aseptic seedlings as a source of explants. The cell culture of L. album was launched from leaf-derived callus in 100 mL Erlenmeyer flasks containing 30 mL of liquid MS medium43, supplemented with 3% sucrose, 2 mg L− 1 naphthyl acetic acid (NAA), and 0.4 mg L− 1 kinetin. The flasks were incubated on a rotatory shaker in the dark at 28 °C. Thereafter, the cells were sub-cultured every 10 days by transferring 2 g of fresh cells into 30 mL of fresh medium. To determine the optimal concentration of Put, the cells were treated with 0.1, 0.2, and 0.5 mM of this polyamine at the 6th day of the cultivation period. After 72 h of exposure, the cells were harvested and the relative dry weight increase rate (RDIR) as well as the lignan content of treated cells were measured. According to the results, the selected Put concentration was added to the cell culture for investigating the mechanism of Put action. The cells treated with the optimal concentration of Put then were harvested at time intervals of 3, 6, 12, 24, and 48 h. To study the relationship between Put and other regulatory molecules, the inhibitors EGTA, AG, imidazole, L-NAME, and TUN were applied. To this, in the beginning, the optimal concentrations of inhibitors were determined (data are not shown), and then they were added to the cell cultures 30 min before Put treatment. Further information on the inhibitors used can be found in Table 1.

Determination of RDIR

To evaluate RDIR, the growth rate (GR) of cells was first calculated using the following formula:

Wa and Wb represent the final and initial weight of cells, respectively. Then, RDIR of the treated cells was calculated through the following formula44:

RDIR (%) =\(\:\:\frac{\text{G}\text{R}\:\text{o}\text{f}\:\text{t}\text{r}\text{e}\text{a}\text{t}\text{m}\text{e}\text{n}\text{t}}{\text{G}\text{R}\:\text{o}\text{f}\:\text{c}\text{o}\text{n}\text{t}\text{r}\text{o}\text{l}}\) × 100

Measurement of H2O2 content

The determination of H2O2 content was done by the method of Velikova et al.45. For this, 0.2 g of fresh cells were extracted in 1.5 mL of 0.1% trichloroacetic acid (TCA) on the ice bath. The resulting mixtures were centrifuged at 12,000 g for 15 min at 4 °C. Then, 0.5 mL of the upper phase was mixed with 0.5 mL of 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) and 1 mL of 1 M potassium iodide (KI). After incubation in the dark for 30 min, the absorbance of the samples was measured at 390 nm using the spectrophotometric method. The content of H2O2 in the samples was calculated according to the standard curve and expressed in µmol g− 1 FW.

NO generation monitoring

Fresh cells (0.2 g) were extracted by 1.5 mL of cold 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) to ascertain NO content. The resulting extracts were centrifuged at 10,000 g for 15 min at 4 °C. 250 µL of centrifuged liquid phase was added to 750 µL of extract buffer and 0.5 mL of grease reagent (0.1% N-naphthylethenyl amide and 1% sulfanilamide in 5% phosphoric acid solution). The mixture was then kept at room temperature for 10 min. The absorbance of samples was measured at 540 nm after incubating time. Based on sodium nitrite standard curve, the content of NO was calculated and reported in µmol g− 1 FW46.

The cytosolic free Ca2 + level measurement

To determine the changes in the cytosolic free Ca2+ concentration, fresh cells were loaded with the free intracellular Ca2+ indicator Fura-2 (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) in the dark at 28 °C for 1 h. Next, the excess dye was removed by washing three times with fresh medium. The Fura-2-loaded cells (200 µL) were pipetted into a black 96-well plate (Greiner, Frickenhausen, Germany), and then treated with Put and different inhibitors (30 min before adding Put). The cytosolic free Ca2+ concentration was measured by recording fluorescent emission from cells at 520 nm using a Cytation 3 Cell Imaging Multi-Mode Microplate Reader (BioTek, Winooski, USA)47.

SA content determination

To measure SA content, 0.5 g of dried cells were ground in 2 mL of methanol with a mortar and pestle. The obtained extract was centrifuged, and the supernatant was evaporated. The residues were dissolved in 4 mL of acetonitrile and then the solutions were washed three times with 2 mL of n-hexane. Finally, the acetonitrile phase was dried. The residue was re-suspended in 0.5 mL of methanol (HPLC grade) to prepare for injection into an HPLC (Agilent Technologies 1260 infinity, USA) with a C18 column (Perfectsil Target ODS-3, 5 μm, 250 × 4.6 mm; MZ Analysentechnik, Mainz, Germany). The eluting solvents were 2% acetic acid in deionized water (A) and methanol (B) flowing at a rate of 1 mL min− 1 in a gradient program (0–2 min: A (95%); 2–10 min: A (75%); 10–20 min: A (60%); 20–30 min: A (50%); 30–40 min: A (0%); 40–50 min: A (95%). The extracts absorption was recorded at 278–300 nm wavelengths by a diode array detector (DAD)48.

Measurement of the contents of free PAs

The extraction of PAs was carried out according to Sharma and Rajam49 method. First, 0.2 g of fresh cells was ground in 5% perchloric acid (PCA) (2 mL), and then the extracts were centrifuged at 13,000 g for 20 min at 4 °C. Next, 150 µL of supernatant was mixed with 200 µL of saturated sodium carbonate and 500 µL of dansyl chloride (5 mg mL− 1). The mixtures were incubated at 60 °C for 1 h in the dark. After that, the incubation continued for 30 min after adding 200 µL of 0.1 g mL− 1 proline to the reaction solution. The dancylated PAs were vortexed after addition of 500 µL of toluene, and the upper phase was collected and evaporated for analysis by means of HPLC (Agilent Technologies 1260 infinity, USA). A C18-ODS3, 5 μm (250 × 4.6 mm) column and a DAD at 254 nm was applied for separation and detection of PAs, respectively. The acidic water (0.01% acetic acid) (A) and acetonitrile (B) with a flow rate of 0.8 mL min− 1 in the gradient program 0 min: A (36%); 40 min: A (80%); 50 min: A (95%), were used as mobile phase50.

Gene expression analysis

Frozen cells were used for extraction of total RNA by RNX™-Plus solution kit (CinnaGen Inc, Tehran, Iran). In the next step, cDNA was produced with 2 µg of total RNA in the reverse transcription reaction using the first-strand cDNA synthesis kit (Fermentas, Burlington, ON, Canada). Quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) was used to analyze the expression levels of PAL and PLR genes with their specific primers (Table 2), and GAPDH gene was applied as an internal standard for normalization51,52. The qPCR amplification program was begun at 95 °C for 10 min, and followed by 35 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s, 60 °C for 15 s, and 72 °C for 10 s (The Applied Biosystems® StepOne™, Thermo Fisher).

Quantification of lignan

Lignan accumulation was measured by the method provided by Yousefzadi et al.52. Accordingly, 0.2 g of dried cells were ground in 2 mL of 80% methanol. The extracts were centrifuged after 20 min of sonication, and the supernatants were evaporated at room temperature. The obtained residues were dissolved in 1 mL of deionized water, and subsequently washed 3 times with acetonitrile. The acetonitrile phase was collected, dried, and re-suspended in 0.5 mL of HPLC grade methanol for injection into the HPLC device (Agilent Technologies 1260 infinity, USA). The stationary phase consisted a C18-ODS3, 5 μm (250 × 4.6 mm) column. The elution solvents including acetonitrile and water were mixed in a gradient program which was mentioned by Ahmadian Chashmi et al.53 to separate various lignans.

Statistical analysis

All the experiments were performed in three biological and technical replicates. The obtained data were analyzed in the SPSS 24 software through One-way ANOVA test. The significant differences (p ≤ 0.05) among different treatment groups were ascertained via Duncan Post Hoc test.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- 6MPTOX:

-

6-Metoxy podophyllotoxin

- AG:

-

Aminoguanidine

- DAO:

-

Diamine oxidase

- EGTA:

-

Ethylene glycol-bis (β-aminoethyl ether)-N, N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid

- Fura2-AM:

-

Fura-2-acetoxymethyl ester

- H2O2 :

-

Hydrogen peroxide

- L-NAME:

-

Nɷ-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester

- NO:

-

Nitric oxide

- NOS-like:

-

Nitric oxide synthase-like

- NOX:

-

NADPH oxidase

- NR:

-

Nitrate reductase

- PAL:

-

Phenylalanine ammonia-lyase

- PLR:

-

Pinoresinol-lariciresinol reductase

- PA:

-

Polyamine

- POA:

-

Polyamine oxidase

- PTOX:

-

Podophyllotoxin

- Put:

-

Putrescine

- SA:

-

Salicylic acid

- Spd:

-

Spermidine

- Spm:

-

Spermine

- TUN:

-

Sodium tungstate

References

Chen, D., Shao, Q., Yin, L., Younis, A. & Zheng, B. Polyamine function in plants: metabolism, regulation on development, and roles in abiotic stress responses. Front. Plant. Sci. 9, 1945 (2019).

Zepeda-Jazo, I. et al. Polyamines interact with hydroxyl radicals in activating Ca2+ and K++ transport across the root epidermal plasma membranes. Plant. Physiol. 157, 2167–2180 (2011).

Amini, S. et al. Effect of cold stress on polyamine metabolism and antioxidant responses in Chickpea. J. Plant. Physiol. 258, 153387 (2021).

Wang, W., Shi, S., Kang, W. & He, L. Enriched endogenous free Spd and Spm in alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.) under drought stress enhance drought tolerance by inhibiting H2O2 production to increase antioxidant enzyme activity. J. Plant. Physiol. 291, 154139 (2023).

Zhang, H. et al. Herbivory by striped stem borer triggers polyamine accumulation in host rice plants to promote its larval growth. Plants 12, 3249 (2023).

González-Hernández, A. I. et al. Putrescine: A key metabolite involved in plant development, tolerance and resistance responses to stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 2971 (2022).

Wang, W., Paschalidis, K., Feng, J. C., Song, J. & Liu, J. H. Polyamine catabolism in plants: A universal process with diverse functions. Front. Plant. Sci. 10, 561 (2019).

Benkő, P., Gémes, K. & Fehér, A. Polyamine oxidase-generated reactive oxygen species in plant development and adaptation: the polyamine oxidase—NADPH oxidase nexus. Antioxidants 11, 2488 (2022).

Pál, M., Szalai, G., Janda, T. & Speculation Polyamines are important in abiotic stress signaling. Plant. Sci. 237, 16–23 (2015).

Liu, J. et al. Putrescine metabolism modulates the biphasic effects of brassinosteroids on Canola and Arabidopsis salt tolerance. Plant. Cell. Environ. 43, 1348–1359 (2020).

Mohammadbagherlou, S. et al. Hydrogen sulfide mechanism of action in plants; from interaction with regulatory molecules to persulfidation of proteins. Nitric Oxide. 156, 27–41 (2025).

Agurla, S., Gayatri, G. & Raghavendra, A. S. Polyamines increase nitric oxide and reactive oxygen species in guard cells of Arabidopsis thaliana during stomatal closure. Protoplasma 255, 153–162 (2018).

Recalde, L. et al. Unravelling ties in the nitrogen network: polyamines and nitric oxide emerging as essential players in signalling roadway. Ann. Appl. Biol. 178, 192–208 (2021).

Adamipour, N. et al. Regulation of stomatal aperture in response to drought stress mediating with polyamines, nitric oxide synthase and hydrogen peroxide in Rosa canina L. Plant. Signal. Behav. 15, e1790844 (2020).

Liu, C. et al. Putrescine elicits ROS-dependent activation of the Salicylic acid pathway in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant. Cell. Environ. 43, 2755–2768 (2020).

Pottosin, I., Velarde-Buendía, A. M., Bose, J., Fuglsang, A. T. & Shabala, S. Polyamines cause plasma membrane depolarization, activate Ca2+, and modulate H-ATPase pump activity in pea roots. J. Exp. Bot. 65, 2463–2472 (2014).

Napieraj, N., Janicka, M. & Reda, M. Interactions of polyamines and phytohormones in plant response to abiotic stress. Plants 12, 1159 (2023).

Mustafavi, S. H. et al. Polyamines and their possible mechanisms involved in plant physiological processes and elicitation of secondary metabolites. Acta Physiol. Plant. 40, 102 (2018).

Nandy, S. et al. Unravelling the multi-faceted regulatory role of polyamines in plant biotechnology, transgenics and secondary metabolomics. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 106, 905–929 (2022).

Suzuki, S. & Umezawa, T. Biosynthesis of lignans and norlignans. J. Wood Sci. 53, 273–284 (2007).

Samari, E., Sharifi, M., Ghanati, F. & Fuss, E. Ahmadian Chashmi, N. Chitosan-induced phenolics production is mediated by nitrogenous regulatory molecules: NO and PAs in Linum album hairy roots. Plant Cell. Tissue Organ. Cult. 140, 563–576 (2020).

Soltani, M. et al. Putrescine induces lignans biosynthesis through changing the oxidative status and reprogramming amino acids and carbohydrates levels in Linum album hairy roots. Plant Cell Tissue Organ. Cult. 153, 387–402 (2023).

Liu, C., Atanasov, K. E., Tiburcio, A. F. & Alcázar, R. The polyamine Putrescine contributes to H2O2 and RbohD/F-dependent positive feedback loop in Arabidopsis pamp-triggered immunity. Front. Plant. Sci. 10, 894 (2019).

Hasan, M. M. et al. Spermine: Its emerging role in regulating drought stress responses in plants. Cells 10, 261 (2021).

Sagharyan, M., Sharifi, M., Samari, E., & Karimi, F. Changes in MicroRNAs expression mediate molecular mechanism underlying the effect of MeJA on the biosynthesis of podophyllotoxin in Linum album cells. Sci. Rep. 14, 30738 (2024).

Tashackori, H. et al. RNAi-mediated Silencing of pinoresinol Lariciresinol reductase in Linum album hairy roots alters the phenolic accumulation in response to fungal elicitor. J. Plant Physiol. 232, 115–126 (2019).

Demiralay, M., Sağlam, A., Yetişsin, F. & Kadioğlu, A. Investigation of the roles of hydrogen peroxide and NADPH oxidase in the regulation of polyamine metabolism in maize plants under drought stress conditions. Tarim Bilimleri Dergisi. 28, 613–625 (2022).

Sun, X., Yuan, Z., Wang, B., Zheng, L. & Tan, J. Exogenous Putrescine activates the arginine-polyamine pathway and inhibits the decomposition of endogenous polyamine in Anthurium andraeanum under chilling stress. Sci. Hortic. 282, 110047 (2021).

Groppa, M. D., Rosales, E. P., Iannone, M. F. & Benavides, M. P. Nitric oxide, polyamines and Cd-induced phytotoxicity in wheat roots. Phytochemistry 69, 2609–2615 (2008).

Sun, X., Yuan, Z., Wang, B., Zheng, L. & Tan, J. Nitric oxide synthase (NOS)-dependent nitric oxide generation is involved in putrescine-induced chilling tolerance of Anthurium andraeanum. Sci. Hortic. 312, 111849 (2023).

Esmaeili, S. et al. Exogenous melatonin induces phenolic compounds production in Linum album cells by altering nitric oxide and Salicylic acid. Sci. Rep. 13, 4158 (2023).

Vazirifar, S., Samari, E. & Sharifi, M. Daily dynamics of intermediate metabolite profiles lead to time-dependent phenylethanoid glycosides production in Scrophularia striata during the day/night cycle. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B. 225, 112326 (2021).

Sagharyan, M., Sharifi, M. & Samari, E. Methyl jasmonate redirects the dynamics of carbohydrates and amino acids toward the lignans accumulation in Linum album cells. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 198, 107677 (2023).

Choudhary, S., Wani, K. I., Naeem, M., Khan, M. M. A. & Aftab, T. Cellular responses, osmotic adjustments, and role of osmolytes in providing salt stress resilience in higher plants: polyamines and nitric oxide crosstalk. J. Plant Growth Regul. 42, 539–553 (2023).

Song, X. G. et al. Involvement of copper amine oxidase (CuAO)-dependent hydrogen peroxide synthesis in ethylene-induced stomatal closure in Vicia faba. Russ J. Plant. Physiol. 61, 390–396 (2014).

Wu, J. et al. Spermidine oxidase-derived H2O2 regulates pollen plasma membrane hyperpolarization-activated Ca2+-permeable channels and pollen tube growth. Plant. J. 63, 1042–1053 (2010).

Marcec, M. J., Gilroy, S., Poovaiah, B. W. & Tanaka, K. Mutual interplay of Ca2+ and ROS signaling in plant immune response. Plant Sci. 283, 343–354 (2019).

Samari, E. et al. Interactions between second messengers, SA and MAPK6 signaling pathways lead to chitosan-induced Lignan production in Linum album cell culture. Ind. Crops Prod. 177, 114525 (2022).

Kolupaev, Y. E. et al. Role of NO synthesis modification in the protective effect of Putrescine in wheat seedlings subjected to heat stress. Appl. Biochem. Microbiol. 57, 384–391 (2021).

Asija, S., Seth, T., Umar, S. & Gupta, R. Polyamines and their crosstalk with phytohormones in the regulation of plant defense responses. J. Plant Growth Regul. 42, 5224–5246 (2023).

Kováčik, J. et al. Lignification and related parameters in copper-exposed Matricaria chamomilla roots: role of H2O2 and NO in this process. Plant Sci. 179, 383–389 (2010).

Sagharyan, M., & Sharifi, M. Metabolic and physiological changes induced by exogenous phenylalanine in Linum album cells. J. Plant Growth Regul. 43, 2785–2801 (2024).

Murashige, T. & Skoog, F. A revised medium for rapid growth and bio assays with tobacco tissue cultures. Physiol. Plant 15, 473–497 (1962).

Liu, H. P., Dong, B. H., Zhang, Y. Y., Liu, Z. P. & Liu, Y. L. Relationship between osmotic stress and the levels of free, conjugated and bound polyamines in leaves of wheat seedlings. Plant Sci. 166, 1261–1267 (2004).

Velikova, V., Yordanov, I. & Edreva, A. Oxidative stress and some antioxidant systems in acid rain-treated bean plants protective role of exogenous polyamines. Plant Sci. 151, 59–66 (2000).

Kaur, G. et al. Exogenous nitric oxide (NO) interferes with lead (Pb)-induced toxicity by detoxifying reactive oxygen species in hydroponically grown wheat (Triticum aestivum) roots. PLoS ONE 10, e0138713 (2015).

Shishova, M. & Lindberg, S. Auxin induces an increase of Ca2+ concentration in the cytosol of wheat leaf protoplasts. J. Plant. Physiol. 161, 937–945 (2004).

Owen, R. W. et al. Isolation, structure Elucidation and antioxidant potential of the major phenolic and flavonoid compounds in Brined Olive Drupes. Food Chem. Toxicol. 41, 703–717 (2003).

Sharma, P. & Rajam, M. V. Spatial and Temporal changes in endogenous polyamine levels associated with somatic embryogenesis from different hypocotyl segments of eggplant (Solanum melongena L). J. Plant. Physiol. 146, 658–664 (1995).

Zafari, S., Sharifi, M., Ahmadian Chashmi, N. & Mur, L. A. J. Modulation of Pb-induced stress in Prosopis shoots through an interconnected network of signaling molecules, phenolic compounds and amino acids. Plant. Physiol. Biochem. 99, 11–20 (2016).

Livak, K. J. & Schmittgen, T. D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2-∆∆CT method. Methods 25, 402–408 (2001).

Yousefzadi, M. et al. Salicylic acid improves Podophyllotoxin production in cell cultures of Linum album by increasing the expression of genes related with its biosynthesis. Biotechnol. Lett. 32, 1739–1743 (2010).

Ahmadian Chashmi, N. et al. Analysis of 6-methoxy Podophyllotoxin and Podophyllotoxin in hairy root cultures of Linum album Kotschy ex Boiss. Med. Chem. Res. 22, 745–752 (2013).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Tarbiat Modares University for providing the laboratory facilities for this project. We also appreciate kindly Iran National Science Foundation (INSF) to provide financial support for this project.

Funding

This work was supported by Iran National Science Foundation (INSF) [Grant Numbers 4004504].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

This research paper was accomplished with the collaboration of all authors. ES performed the experiments, analyzed data and wrote the manuscript. MSH designed and supervised the study. MS performed the experiments and edited the manuscript. RHS and FK were the study advisor and had supportive role in the investigation and methodology.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Samari, E., Sharifi, M., Karimi, F. et al. Regulation of lignan biosynthesis through signaling pathways mediated by H2O2 in Linum album cell culture in response to exogenous putrescine. Sci Rep 15, 13553 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96019-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96019-1