Abstract

This research concentrates on an introduction of a multi-model approach integrating Bayesian Networks (BN), Machine Learning (ML) models, Natural Language Processing (NLP) with Sentiment Analysis, Agent-Based Modeling (ABM), and Survival Analysis to improve predictive modelling of accident causation in high-risk steel industries. The significance of the artificial intelligence (AI) based models is that every approach complements other substantiating the hypothesis. Also, the augmentation of prediction accuracy could be achieved through AI approaches contrary to conventional methods. Results reveal that the application of AI model improves the prediction accuracy compared to conventional approaches. BN application uncovers the machine conditions and human errors responsible for causing accidents. Gradient Boosting Machines discussed equipment-related incidents, while NLP analysis demonstrated negative sentiment due to non-compliance with safety protocols. Moving forward, ABM simulations in accidents focus on personal protective equipment (PPE) compliance and machine maintenance. Survival analysis indicated the role of timely interventions in reducing severe accidents. Additionally, temporal insights aid in timing interventions, improving safety strategy efficacy. The outcome of this research discusses advancements in proactive accident prediction and risk management in high-risk steel industrial environments by addressing latent risk factors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Accident prevention is a cardinal constraint to safeguard lives, assets, resources and infrastructures in risk-prone circumstances like industries, environment, and manufacturing sectors1,2. Operating in such risk prone environment can rapidly escalate minor issues into catastrophic events3. According to Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), about 846,700 injuries are reported in manufacturing firms, which signifies around 6.6 cases per 100 full-time workers or 15 percent of all nonfatal injuries and illnesses4. So, for proper hazard identification, root cause assessment, risk mitigation measures, effective accident analysis is essential4,5. Conventional analysis systems focused on the reactive reporting, lacking the ability to anticipate future incidents proactively and avoid their occurrence. An augmented focus on safety and regulatory compliance has compelled the need for the applications of predictive risk assessment models for proactive accident management6,7. Regardless of stringent safety protocols and rigorous protection advancements, proactive prediction of accidents and critical risk factors identification remain challenging owing to complex interplay of human behavior and ecosystem conditions. Factors like the applications of personal protective equipment (PPE), machine condition monitoring, hazard management influence the risk of accident, however the interactions are limited to nonlinearity and are very much context-dependent8,9. Conventional and standard modelling attempts may not acquire complications and densities, resulting in shortcomings of accident prevention and management. Also, versatile accident data sources including structured applications of operational metrics and vague incident reports, command the requirements of sophisticated approaches for effective analysis10,11.

The objective of this study is to focus on the development of a comprehensive AI framework integrating Bayesian Networks (BN), Gradient Boosting Machines (GBM/XGBoost), Random Forest (RF), Natural Language Processing (NLP) with Sentiment Analysis, Agent-Based Modeling (ABM), and Survival Analysis to improve prediction exactness in accident investigation and recommend acumens for accident sources in steel plants. Through integration of these techniques, the research strives to enhance safety management processes around risk assessment model analysis in highly complex steel industries. Steel industries are considered owing to the fatalities and high frequency of accidents influencing the safety concerns and unsafe working conditions amongst industries. The adoption of such AI approach helps in proactive risk management and accident analysis for industries. The novelty of this research lies in the applications of a multi-model AI framework overcoming the limitations of conventional methods. The benefit of using multi-model approaches is that such approaches involve the use of multiple methods where the shortcoming of a particular approach is complemented by another one, thus enhancing the prediction accuracy of accidents in highly dynamic steel industries. For instance, the applications of BN capture probabilistic dependencies, allowing for a deep understanding of causality and uncertainty in accident outcomes. Further the applications of Machine Learning (ML) models viz. GBM/XGBoost and RF recognize intricate patterns in data and feature influential risks. NLP extracts important information from unstructured data, interpreting it and finally providing a concrete understanding of the accidents. ABM facilitates simulating interactions between various resources such as workers, equipment, and offers recommendations regarding contributing factors to accidents. Survival analysis predicts likelihood and timing of accidents efficiently and investigates the timely interventions. The employment of such integrated methodologies helps in expanding the prediction capabilities, hence providing a multi-dimensional perspective to accident assessment.

The method adopted in this research will help in achieving better prediction performance using BN and ML models which manage balancing of probabilistic reasoning and pattern recognition, NLP facilitating integration of textual data insights, ABM in reveal intervention points, and survival analysis offering perceptions into accident relapse. The framework helps in the development of a robust, data-driven safety strategy for complex industrial settings. Further, it develops a multimethod attempt that bridges the limitations between predictive accuracy and causal understanding, developing risk management potential in steel manufacturing environment.

Literature review

The analysis of accidents in risk prone steel industries counts on advanced modelling attempts to develop the prediction accuracy of uncertainties. BN have garnered importance in their ability to exhibit dependencies, capturing complexities in relationships, and measuring uncertainties12. Besides, the applications of BN in identification and assessment of risk factors across disciplines such as aviation, construction, healthcare are plenty13. For instance, Bayesian safety analyzers demonstrate the role played by BN in handling structured data sets and supporting risk assessment and management applications. Conversely, BN are designed by their influence on predefined relationships, which can overlook complex relationships for nonlinear factors with miscellaneous datasets.

ML models focus on a combination of methods like RF, Support Vector Machines, and Neural Networks, which offer considerable predictive capabilities through automatic identification of patterns with widespread datasets14,15. These approaches have established augmented accuracy in prediction of accident likelihood for safety, maritime incidents, and occupational health applications. An ML-based framework was developed to address encounters in data integration for incident likelihood analysis, which stresses the need for distinct data sources16,17. Yet, the limitations of ML models are that they function as “black boxes,” lacking interpretability of predictions, posing significant challenges to recognizing the accident causes and risks18,19. Current advancements, like the integration of probabilistic models with ML algorithms, point to providing estimates for uncertainties, however, transparency remains a challenge.

NLP models are influential in extracting information from unstructured data sets and texts involving reports, logs, and reviews20. NLP helps in transforming narrative data into structured formats uncovering acumens for improved accident analysis. Notable progressions, such as an incorporation of generative AI methods viz. Large Language Models (LLMs) with chain-based mechanisms have improved the localization aspects of accident entities thereby enabling better results21,22,23,24. The application of NLP in safety management is emerging with increased studies in the domain, hence indicating its potential.

ABM serves to be paramount for behavior simulation and analyzing interactions within the systems such as the dynamic relations between the manufacturing resources and safety protocols. The ABM models helps in the analysis of complicated scenarios, providing insights into risk patterns and investigating the impact of agent behaviors on accident outcomes25,26,27. The approach has been applied in the domains of industrial safety and evacuation, offering a concrete view of advancement over time. Nevertheless, the employment of ABM in isolation restricts the predictive power of data-driven models28,29,30. Hence, there is a need for an integration of ABM with real-world data sources that would enhance its applicability through accurate and context-specific simulations. More specifically, for steel industries there is a lack in users of such type of analysis.

Current research in steel industries’ safety is more focused on the environment, strategies, and prediction measures through use of a particular method. The research gap lies in the siloed applications of the modeling procedures, with a focus of each approach on specific aspect of accident analysis often lacking holistic perspective of the phenomenon. Despite the availability of research in the domain of accident prediction for process industries, they are focused on the use of a particular algorithms such as artificial neural networks (ANN), support vector machine (SVM), and BN31,32,33. However, there is a scarcity in research focusing on the use of AI based models for accident prediction and risk assessment for steel industries. The applications of the multi-model AI approaches will help in enhancing the prediction accuracy of the safety management systems which couldn’t be done through conventional models.

This research emphasizes the multi-model integration of the AI approach that leverages the unique strengths of each approach to address the complexities of accident and risk management for steel industries. The study bridges the gaps by integrating BN, Gradient Boosting Machines (GBM/XGBoost), RF, and NLP with Sentiment Analysis, ABM, and Survival Analysis into a unified framework for prediction modelling of accidents and risk management studies in dynamic steel environments. Such a comprehensive method provides better prediction accuracy with rich insights. Through the synthesis of these approaches, the research enables a dynamic and rigorous analysis considering structured and unstructured data, complex behavioral interactions and risk factors, hence enhancing predictive modelling capabilities contributing to the development of a holistic assessment model. Such a model is instrumental for the growth of safety management solutions and recommending proactive risk mitigation strategies in uncertain dynamic steel manufacturing environments. By doing this, the steel industries can get a platform to accurately predict risks and manage them proactively thus reducing accidents and deaths in hazardous environments.

Methodology

This section provides a comprehensive discussion about the methodology adopted in the research. Also, a brief discussion about the AI approaches adopted along with their mathematical formulations are also outlined.

Data description

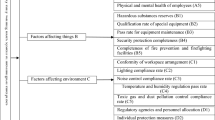

The dataset utilized in this study spans incident records from 2018 to 2023, focusing on safety–critical environments within the steel industry. It comprises several features that facilitate a comprehensive accident causation analysis and risk assessment. The dataset provides a detailed overview of incidents, allowing for an analysis of temporal trends and the specific risk factors that influence incident outcomes. The process flow for the research method is shown in Fig. 1.

-

Designation This variable refers to the role or position of the individual involved in the incident, such as Worker, Operator, Engineer, Helper, Vehicle driver, Loco/crane operator, manager, security guard, etc.

-

Employment Type This variable indicates the individual’s employment type, distinguishing between Regular and Contract employees.

-

PPE (Personal Protective Equipment) This variable specifies whether the individual was equipped with personal protective gear during the incident, denoted as Yes or No.

-

Machine Condition This variable describes the condition of the machine involved in the incident, categorized as Machine Idle (MI), Machining Running (MR), or Not related to the machine (NMR).

-

Observation Type This variable classifies the type of observation made during the incident, such as:

-

Unsafe Act (UA) This category indicates instances where the individuals are responsible for causing the incident.

-

Unsafe Act and Unsafe Condition (UAUC) This category denotes incidents resulting from the individual’s actions and hazardous conditions.

-

Unsafe Act by Others (UAO) This category represents incidents caused by the actions of someone other than the individual directly involved in the incident.

-

Unsafe Condition (UC) This category refers to situations with inherent risks likely to lead to incidents.

-

Primary Cause This variable identifies the predominant event or circumstance leading to the occurrence of an incident. They are Slip/Trip/Fall (STF), Failure of Positive Isolation (FPI), Poor Road Condition (PRC), Negligent Driving (ND), Fall from Height (FFH), Driver Lost Control of Vehicle/Equipment (DLC), Mining Equipment Hit the Roof/Wall (MEH), Person Not Followed Mining Guidelines (PNF), Availability of Flammable Materials (AFM), Side Fall of Material (SFM), Scotch Block (SB), Fall of Object (FO), Electrical Fault (EF), Dashing or Collision (DC), Electrical Cable Damage (ECD), Toxic Release (TR), and Damaged Gas Line (DGL) etc. Each category represents a unique aspect of incident causality, providing valuable insights for incident analysis and prevention efforts.

-

Location Areas within the facility where incidents occurred, with locations such as Steel Making Mechanical Maintenance, TSJ LD1, Hot Metal Logistics, Blast Furnace, Pellet Plant, Security, and other operational zones that may pose unique risks.

-

Impact This variable refers to the consequences or outcomes of incidents. It categorizes the effects of incidents into different classes based on their severity or nature as First Aid, Foreign Body, Ex-Gratia, Equipment/Property Damage, Fire, Toxic Release, Uncontrolled Environmental Discharge, Derailment, LTI, Fatality, No Injury/Impact, IOD- LTI, IOD- First Aid.

Data preprocessing

Data preprocessing involved several critical steps to prepare the dataset for modeling:

-

Handling Missing Data Missing values were identified across multiple columns. Depending on the feature, various methods were employed to handle these gaps. For categorical fields, missing values were imputed with the mode, while numerical fields were filled with the median. If missing values were extensive and critical information was missing, those records were excluded to maintain dataset quality.

-

Encoding Categorical Variables Many features in the dataset are categorical, including Designation, Employment Type, Machine Condition, and Primary Cause. Label Encoding was applied for binary fields like PPE (Yes/No), while One-Hot Encoding was used for multi-category features to ensure that ML algorithms could process these features without assuming any ordinal relationships.

-

Feature Scaling Although not strictly necessary for all models, standard scaling was applied to numerical features, especially to improve training efficiency and ensure comparability between features with vastly different scales.

-

Dataset Splitting The dataset was split into three parts to ensure robust model training and validation. A 60-20-20 split was implemented: 60% of the data was used for training, 20% for testing, and the remaining 20% for validation. This distribution allowed for reliable model evaluation, ensuring that models could generalize to unseen data without overfitting.

This preprocessing standardizes the dataset, enabling efficient and accurate modeling. The comprehensive preparation of datasets is the foundation for building robust predictive models and extracting meaningful insights for safety management in the risk-prone steel industry.

Machine learning (ML) models

This study employs six distinct models to analyze accident causation, evaluate risk factors, and extract insights for accident prevention. These different models include ABM, BN, Gradient Boosting Machines (GBM/XGBoost), NLP with Sentiment Analysis, RF, and Survival Analysis. Each model offers a unique perspective, providing predictive analytics, probabilistic relationships, sentiment trends, and time-to-event analysis, which enables a thorough assessment of accident data.

Gradient boosting machines (GBM/XGBoost)

XGBoost has been used as a multi-class classification model that can predict different accident outcomes utilizing features such as Designation, PPE usage, Machine Condition, and Observation Type. This model optimizes gradient boosting to iteratively reduce classification error by leveraging an ensemble of weak decision trees. The objective function for XGBoost can be expressed as in Eq. (1):

where L(θ) is the overall loss function; \(\ell \left( {y_{i} ,\hat{y}_{i} } \right)\) represents the loss between the true label (yi) and the predicted label (\(\hat{y}_{i}\)); \(\Omega \left( {f_{k} } \right)\) is the regularization term for each tree (fk) to avoid overfitting; N is the number of training examples, and K is the number of trees in the ensemble.

Cross-validation has been applied to fine-tune key hyper-parameters, including learning rate, maximum depth, number of estimators, and regularization parameters (e.g., gamma, lambda), which significantly enhanced model performance. The optimal combination is identified using a grid search with fivefold cross-validation, ensuring a balance between model complexity and predictive accuracy. Model accuracy in classifying accident outcomes has been assessed by applying standard evaluation metrics, including: Accuracy in Eq. (2), Precision in Eq. (3), Recall in Eq. (4) and F1-Score in Eq. (5).

Accuracy It measures the percentage of correct predictions.

Precision It indicates the proportion of true positive predictions among all predicted positives.

Recall It reflects the model’s ability to identify all relevant instances.

F1-Score It is the harmonic mean of precision and recall, which balances both metrics.

Confusion Matrix It shows the true vs. predicted classifications, which enables a detailed assessment of model performance across classes.

Bayesian network analysis

BN represent directed acyclic graphs that capture probabilistic relationships between variables, representing dependencies within the dataset. Each node in the network corresponds to a feature (e.g., Designation, PPE usage, Machine Condition), whereas directed edges signify conditional dependencies. These networks facilitate the understanding of how variations in one feature may affect others, offering valuable insights into accident causation.

For a given BN, the joint probability distribution of all variables in the network is expressed as in Eq. (6):

\(P\left( {X_{i} |Parents\left( {X_{i} } \right)} \right)\) shows the conditional probability of \({X}_{i}\) given its parent nodes in the network.

This equation explains that the joint probability of all variables can be broken down into the product of conditional probabilities, forming the core principle of BN.

Conditional Probability Tables (CPTs) estimate the probability of each outcome based on the values of parent nodes. Each node in a BN is associated with a CPT, which defines its conditional probability distribution given by its parent nodes. For a node \(XXX\) with parent nodes \(AAA\) and \(BBB\), the conditional probability of \(X\) given \(A\) and \(B\) is represented as in Eq. (7):

The probabilities in each CPT are critical for evaluating the likelihood of different accident outcomes based on observed variables. This model enables probabilistic insights by computing the posterior probability of outcomes based on observed evidence. Using Bayes’ theorem, the probability of an event \(E\) given evidence \(F\) is calculated as in Eq. (8):

where \(P\left( {E|F} \right)\) is the posterior probability of E given F; \(P\left( {F|E} \right)\) is the likelihood of observing F given E; P(E) is the prior probability of E; P(F) is the marginal probability of F.

NLP for sentiment analysis

NLP has been applied for text preprocessing prior to accident reports analysis and safety observations. This includes several key actions to prepare textual data for the sentiment analysis:

-

Text Cleaning It removes special characters, punctuation, numbers, and drop words that do not add meaning (common words like “the” and “is”).

-

Tokenization It splits text into individual words or tokens for analysis.

-

Stemming and Lemmatization It reduces words to their base or root form while retaining the meaning; ex: “running” is reduced to “run”.

Let T represent the original text, and let \({T}_{processed}\) denote the processed text, where each token \({t}_{i}\) is transformed as follows in Eq. (9):

where each \({t}_{i}\) is a stemmed or lemmatized token from the original text \(T\).

Sentiment analysis has been used to score each report’s sentiment polarity, indicating whether the sentiment is positive, negative, or neutral. Using tools like VADER or Text Blob, each text \({T}_{processed}\) is assigned a sentiment score \(S\) on a scale from − 1 (very negative) to + 1 (very positive) as in Eq. (10):

where \(S\left( {T_{processed} } \right) > 0\) indicates positive sentiment, \(S\left( {T_{processed} } \right) < 0\) indicates negative sentiment, \(S\left( {T_{processed} } \right) = 0\) indicates neutral sentiment.

The patterns within incident reports are uncovered utilizing theme extraction conducted using \(TF-IDF\) (Term Frequency − Inverse Document Frequency) and Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA).

Term Frequency-Inverse Document Frequency \(\left(TF-IDF\right)\): It measures the importance of a term \(t\) in a document \(d\) relative to all documents D. The \(TF-IDF\) score for a term \(t\) in document \(d\) is given by in Eq. (11):

where \(TF\left( {t,d} \right)\) is the term frequency of t in d; \(IDF \left( {t,D} \right) = \log \left( {\frac{\left| D \right|}{{\left| {\left\{ {d \in D:t \in d} \right\}} \right|}}} \right)\) is the inverse document frequency, which reduces the weight of terms that are common across many documents.

Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA): It is a probabilistic model used for topic extraction within a corpus. Each document \(d\) is modeled as a distribution over topics \(\theta d\), and each topic k is a distribution over words \(\phi k\). The probability of the word www in a document \(d\) is given by in Eq. (12):

where \(P\left( {w|d} \right)\) is the probability of word www given document d; \(P\left( {w|z = k} \right)\) is the probability of word www given topic k; \(\mathop \sum \limits_{k = 1}^{K} P\left( {w|z = k} \right) \cdot P\left( {z = k|d} \right)\) is the probability of topic k given document d.

Agent-based modeling (ABM)

In this model individual entities called agents interact within a simulated environment. The primary agents in safety–critical environments for accident analysis include: Worker, machines, environment, and safety protocols. Each agent operates as per predefined rules and behaviors, interacting with other agents and adapting to environmental conditions. This approach makes the simulation of complex, real-world scenarios possible. Multiple simulation scenarios are designed to examine how agent interactions influence accident likelihood and severity. These scenarios may include Non-compliance Scenarios, machine malfunctions, and Environmental Changes. For each scenario, the model tracks the occurrence of accidents under varying conditions, capturing how agent interactions escalate or mitigate risks. It also allows for the inclusion of feedback loops where agents adjust their behaviour based on observed accidents, as an example in Eq. (13).

This function adjusts an agent’s behavior after an accident, such as a worker becoming more cautious or safety protocols becoming stricter. Simulation outcomes also include the frequency and type of accidents, which helps identify high-risk behaviors and machine conditions. Feedback loops enable the model to simulate how interventions (e.g. stricter PPE enforcement) influence accident rates over time.

Random forest

It is an ensemble learning technique that utilizes multiple decision trees to enhance prediction accuracy and mitigate over-fitting. Each decision tree is trained on a subset of the data and makes independent predictions. The final output is obtained by aggregating the predictions of all trees, either by using majority voting for classification or by averaging for regression. In accident analysis, this model classifies outcomes by evaluating features such as Designation, PPE usage, Machine Condition, and Observation Type. The prediction of the RF model for a given input \(X\) is defined as in Eq. (14):

\(\hat{y}\) is the final predicted outcome; T is the total number of decision trees in the forest; ft(X) represents the prediction from the t-th decision tree for input X.

This model provides an estimate of feature importance, showing the most influential variables in predicting accident outcomes. Feature importance for a feature \({X}_{j}\) can be calculated based on the decrease in impurity (e.g., Gini impurity or entropy) across all trees in the forest. The importance \(I\left({X}_{j}\right)\) of feature \({X}_{j}\) is given by in Eq. (15):

where \(I\left( {X_{j} } \right)\) is the importance of feature Xj; \({\Delta }I_{t} \left( {X_{j} } \right)\) is the decrease in impurity for feature Xj in the tree t; T is the total number of trees in the forest. The performance of the RF model has been optimized by using cross-validation to tune key hyperparameters, including:

-

Number of Trees (“\(n\)” estimators): The number of deciding trees in the forest.

-

Maximum Depth: The maximum depth of each tree.

-

Minimum Samples Split: The minimum number of samples required to split an internal node.

-

Minimum Samples Leaf: The minimum number of samples required to be at a leaf node.

Grid search with cross-validation is applied to find the optimal combination of hyperparameters that maximize accuracy while minimizing overfitting. To evaluate the performance of the RF model in predicting accident outcomes, the following metrics were used:

-

Accuracy The ratio of correct predictions to the total number of predictions.

-

Precision The ratio of true positive predictions to the total predicted positives.

-

Recall The ratio of true positives to actual positives.

-

F1-Score The harmonic means of precision and recall.

-

Confusion Matrix A matrix representation of true vs. predicted classifications for each accident outcome.

Survival analysis

It is a statistical method used to predict the time until an event occurs, such as an accident or failure. Accident analysis aids in estimating the duration between accidents and evaluating the influence of various factors on accident recurrence. This technique is especially valuable in safety–critical industries, to understand the longevity of safe conditions and identify high-risk periods.

Key elements in survival analysis:

-

Time to Event (Survival Time): It is the time interval from the start of observation until the occurrence of the event (e.g., accident or safety failure), often measured in days, weeks, or months.

-

Event Indicator: It is a binary variable indicating whether the event of interest occurred (1 = event occurred, 0 = censored). Censoring occurs when the exact event time is unknown, such as when an observation period ends before an accident happens.

The Kaplan–Meier Estimator is used to estimate the survival function, which represents the probability of surviving (or remaining accident-free) beyond a given time \(t\). The Kaplan–Meier survival function \(S\left(t\right)\) is calculated as in Eq. (16):

where, S(t) is the survival probability at time t, \(t_{i}\) represents the time of each observed accident event; \({d}_{i}\) is the number of events (accidents) that occurred at time ti; \({n}_{i}\) is the number of individuals at risk just before time ti.

The Cox Proportional Hazards Model is used to assess the effect of multiple covariates (e.g., PPE usage, machine condition, or observation type) on the hazard rate, which is the risk of the event occurring at the time \(t\). The hazard function \(h\left(t\right)\) for an individual with covariates \(X=\left({X}_{1}, {X}_{2}, \dots , {X}_{P}\right)\) is defined as in Eq. (17):

where, \(h\left( {t|X} \right)\) is the hazard function for an individual with covariates X; \({h}_{0}\left(t\right)\) is the baseline hazard function (the hazard when all Xi = 0); \({\upbeta }_{1}, {\upbeta }_{2, }\dots .{\upbeta }_{p}\) represents the regression coefficient for each covariate Xi.

This model assumes that the effect of each covariate is proportional over time, meaning the hazard ratio remains constant. The coefficients \({\beta }_{i}\) indicate how each covariate affects the risk of an accident, with positive coefficients implying an increased hazard and negative coefficients implying a reduced hazard.

Results and discussion

This section focuses on the details about the study findings outlining the results and their interpretations.

Results of machine learning (ML) models

The results of the ML-based models are summarized and discussed next.

Gradient boosting machines (GBM/XG Boost)

Figures 2, 3, and 4 show the Feature Importance, Confusion Matrix, and ROC Curve with AUC scores, respectively, while Table 1 presents the result summary of the classification report for GBM results. The feature importance analysis in Fig. 2 highlights the model’s key predictors, which play a substantial role in determining the model’s decision-making process. “Primary Cause,” “Observation Type,” and “Location” emerge as the most significant features, suggesting their strong association with high-incident categories. Notably, “PPE” and “Machine Condition” show relatively lower importance, indicating limited impact on the model’s predictions. These insights are valuable for prioritizing risk mitigation strategies by focusing on the most influential variables.

The confusion matrix in Fig. 3 offers a detailed view of the model’s classification tendencies across various categories. Certain classes, like “Equipment Property Damage” and “Derailment,” show a higher number of correct predictions, reflecting the model’s strength in these areas. However, the model struggles significantly with rare events, such as “Fatality,” “Foreign Body,” and “IOD” (Injury on Duty), which have zero correct classifications due to limited data representation. The high misclassification rates for these rare categories highlight the need for additional data balancing or model tuning to improve accuracy for underrepresented incident types.

Figure 4 presents the ROC curves, showing varying AUC scores across incident types. The model exhibits strong discriminatory power for classes such as “Pumping” (AUC = 0.97), “Toxic Release” (AUC = 0.91), and “Fire” (AUC = 0.89), indicating high predictive accuracy for these events. Conversely, the model underperforms for classes like “Winders” (AUC = 0.23) and “12 Seam” (AUC = 0.06), suggesting difficulty in distinguishing these rare events. This discrepancy emphasizes the need for model adjustments, such as enhancing the training process or employing resampling techniques, to improve performance across all classes.

Table 1 shows classification metrics, with an overall test accuracy of 53.55% and a validation accuracy of 53.21%, indicating moderate performance across the dataset. The macro average F1-score of 0.30 and weighted average F1-score of 0.51 demonstrate that the model performs relatively well for more frequent classes, such as “Equipment Property Damage” (F1-score = 0.66) and “First Aid.” However, classes with very low support, like “Fatality” and “Foreign Body,” have poor precision and recall due to their rarity, which impacts the model’s overall effectiveness. The high variance between train (90.57%) and test accuracy suggests potential overfitting, necessitating further optimization to enhance generalization and improve performance for less common incident categories.

Thus, the GBM/XGBoost model displays robust predictive capability for prevalent incident types but encounters challenges in accurately identifying rare events due to data imbalance. High AUC scores for specific categories indicate strong model performance when sufficient data is available, while low scores for rare incidents signal the need for focused improvements. Future work should involve addressing class imbalance, possibly through resampling or additional regularization, and exploring new feature engineering approaches to boost predictive accuracy across all categories, particularly for underrepresented incidents.

Bayesian network analysis

Figures 5, 6, and 7 show the feature importance, confusion matrix, and ROC Curve with AUC scores, respectively, while Table 2 presents the summary of the classification report for BN analysis model results. Figure 5 shows primary variables influencing the BN analysis model’s predictions, with “Primary Cause” emerging as the most significant predictor, followed by “Observation Type” and “Machine Condition.” These features provide critical information that aids the model in differentiating between incident types, particularly in high-incident categories. Conversely, features like “PPE” and “Employment Type” have relatively low importance scores, suggesting they play a limited role in the model’s decision-making process. This understanding of feature significance is valuable for prioritizing resources in incident prevention efforts, focusing on variables that heavily influence predictions.

The confusion matrix in Fig. 6 provides a detailed breakdown of actual versus predicted classifications, revealing the BN analysis model’s varying performance across different classes. The model demonstrates relatively high accuracy for frequently occurring classes like “Equipment Property Damage” and “Ex-Gratia,” where predictions align closely with actual classifications. However, rare incident types, such as “Fatality,” “Foreign Body,” and “IOD-First Aid,” show no correct classifications, reflecting challenges in distinguishing these events due to data sparsity. Misclassifications are also observed in instances of “First Aid” and “Machinery Malfunction,” underscoring the need for model fine-tuning or data rebalancing to enhance prediction accuracy in underrepresented categories.

The ROC curves in Fig. 7 illustrate the BN analysis model’s discriminatory ability across classes, with AUC scores showing significant variability. High AUC values for classes suggest strong predictive performance in these areas, indicating that the model effectively distinguishes these categories when data is sufficiently represented. In contrast, classes with low AUC scores, suggests that the model struggles to differentiate rare events from others. This performance discrepancy suggests that while BN analysis can effectively classify certain frequent categories, additional efforts are needed to enhance its ability to handle less common incident types.

Table 2 provides a comprehensive summary of the BN analysis model’s classification performance, with an overall test accuracy of 49.87% and a validation accuracy of 49.25%, indicating moderate effectiveness. The macro average F1-score of 0.26 and weighted average F1-score of 0.40 reveal that the model performs better for more frequent classes, such as “Ex-Gratia” (F1-score = 0.61) and “Equipment Property Damage” (F1-score = 0.43), while rare categories like “Fatality” and “Foreign Body” suffer from low precision and recall. The discrepancy between train accuracy (87.64%) and lower test accuracy suggests potential overfitting, where the model performs well on training data but struggles to generalize on unseen data. This limitation underscores the need for further model optimization and regularization techniques to improve its adaptability. Thus, the BN analysis model demonstrates satisfactory predictive capabilities for prevalent incident types, showing high AUC scores for classes with ample data representation. However, it encounters challenges with rare events due to data imbalance, resulting in moderate overall accuracy and limited effectiveness for underrepresented classes. The findings suggest that while BN analysis can successfully classify certain dominant categories, improvements are necessary to achieve balanced performance across all incident types. Limitations in BN analysis involved addressing class imbalance, refining network structures, and incorporating additional features to enhance prediction accuracy, especially for rare incidents. This approach would foster a more robust and generalizable model suitable for diverse and unevenly represented incident types which can be a potential direction for future work.

Natural language processing (NLP) for sentiment analysis

Figure 8 illustrates the distribution of sentiment across various primary causes, providing insight into the overall sentiment associated with each cause of incidents. In contrast, Fig. 9a–f presents a detailed visual analysis through word clouds, including the Word Cloud of Incident Descriptions, which captures common terms used in incident reports; the Word Cloud of Negative Incidents, highlighting terms frequently associated with unfavorable outcomes; the Word Cloud of Neutral Incidents, showing terms related to neutral events; the Word Cloud of Positive Incidents, emphasizing language linked to positive or less severe occurrences; the Word Cloud of Observation Types, which categorizes key words by type of observation; and the Word Cloud of Primary Causes, focusing on terms most often associated with primary causal factors. Together, these figures offer a comprehensive view of sentiment and terminology patterns in incident data. Figures 8 and 9a–f provide a detailed sentiment and terminology analysis of incident reports, illustrating language patterns and sentiment distribution linked to various primary causes of incidents. Figure 8 shows the sentiment distribution across primary causes, categorizing incidents into positive, neutral, or negative tones. This sentiment analysis helps to gauge the general perception surrounding different types of incidents, enabling prioritization of areas with higher negative sentiment for timely intervention and risk management.

Figure 9a–f presents a series of word clouds that delve into specific aspects of incident reporting and analysis:

-

Word Cloud of Incident Descriptions This visualization aggregates frequently used terms across incident reports, revealing common patterns and themes. Words like “Slip,” “trip,” “fall,” and “Hit” appear prominently, indicating that physical incidents are frequent and may require focused preventive strategies to reduce their occurrence.

-

Word Cloud of Negative Incidents This word cloud emphasizes terms associated with high-risk or severe incidents, such as “Unsafe condition,” “fault,” and “hazardous.” These terms highlight critical factors contributing to negative outcomes, guiding safety protocols toward addressing these risk-inducing conditions. This visualization underscores the need for proactive measures to manage identified risk factors.

-

Word Cloud of Neutral Incidents This word cloud captures terms associated with incidents that are neither distinctly negative nor positive. Terms like “Machine Condition” and “Observation” suggest that these incidents may be more observational or routine, contributing to safety logs without significant impact. Recognizing these patterns helps differentiate between high-risk incidents and general observations, allowing for more nuanced incident tracking.

-

Word Cloud of Positive Incidents In this visualization, terms associated with less severe incidents or successful mitigations, such as “responsible,” “likely,” and “act,” dominate. These terms indicate areas where safety measures are effectively implemented, with outcomes being managed or controlled. This word cloud can inform best practices by highlighting terms associated with successful interventions and outcomes.

-

Word Cloud of Observation Type Fig. 9e, shows word cloud focuses on terminology associated with observation types. Terms like “Unsafe condition,” “representing,” and “likely” indicate the types of conditions typically noted during observations, providing insights into prevalent safety concerns that may require regular monitoring.

-

Word Cloud of Primary Causes This word cloud highlights terms most associated with root causes, such as “cause,” “Unsafe act,” and “condition.” The recurring presence of terms like “person,” “representing,” and “likely” points to human factors as a critical component in incident causation, suggesting a need for human-centric interventions. Addressing these root causes through targeted training and awareness programs could help mitigate the recurrence of similar incidents.

Together, Figures 8 and 9a–f offer a comprehensive view of sentiment and terminology patterns within incident data. By analyzing the distribution of sentiment and identifying frequently used terms tied to incident causes, safety management practices can be better informed. Areas associated with negative sentiment can be prioritized for immediate intervention, while positive terms indicate successful safety practices that could be reinforced. The prominence of human factors in incident causation further underscores the need for focused training programs to address common risky behaviors. Collectively, these insights enable organizations to develop targeted safety measures, fostering a safer workplace environment through both preventive and corrective strategies.

Agent-based modeling (ABM)

The ABM approach is instrumental in understanding the dynamics of workplace safety risks, as demonstrated by Figs. 10 and 11. ABM simulates complex systems by modeling individual agents, each with specific behavior patterns and interactions, to observe how these interactions contribute to emergent system behaviors. In safety and risk management, ABM can illustrate how factors like machine condition and PPE compliance influence accident risks, providing valuable insights for enhancing workplace safety protocols.

Figure 10 presents a risk heatmap that evaluates safety risks based on PPE compliance (Yes or No) and machine conditions (Good or Poor). The results reveal distinct patterns:

High Risk with Non-Compliance and Poor Machine Condition takes place with the highest risk (3.2) occurs when PPE is non-compliant, and the machine condition is poor. This critical risk level underscores the compounded hazards arising from neglecting both equipment maintenance and safety protocols. Moderate Risk with Partial Compliance occurs if either PPE compliance or machine condition improves individually, the risk decreases to moderate levels (1.5 to 2), indicating that each factor independently contributes to accident mitigation, albeit partially. Low Risk with Full Compliance and Good Machine Condition have the lowest risk (0.93) is observed when both PPE compliance is maintained, and machine condition is good. This finding demonstrates the preventive power of maintaining both individual and mechanical safeguards, highlighting the need for integrated safety protocols that address both human compliance and equipment maintenance. This heatmap visually conveys how different combinations of compliance and machine condition affect overall risk, offering decision-makers a clear basis for prioritizing safety interventions where they will have the greatest impact.

Figure 11 shows cumulative number of accidents over successive simulation steps. The curve reveals a rapid initial increase in accidents, which plateau around step 6. This progression suggests two critical insights:

-

Initial Surge in Accidents In the early simulation stages, accidents rise sharply as agents interact with poor safety conditions, reflecting real-world scenarios where initial lapses in compliance or equipment issues lead to an uptick in incidents.

-

Stabilization Over Time After step 6, accident numbers stabilize at around 5250. This plateau could signify that once certain safety measures are implemented or conditions improve, further increases in accident rates are mitigated. It also implies a potential saturation point where systemic risks remain constant despite improvements, suggesting the need for ongoing safety efforts.

This temporal analysis highlights the urgency of early intervention, as preventing initial surges in accidents can reduce overall risk. It also provides insights into how risks evolve over time, helping organizations identify critical intervention periods.

The ABM approach offers significant advantages for safety and risk assessment by enabling the representation of individual agents such as workers and machines with specific attributes like PPE compliance and machine condition. This granularity allows ABM to simulate how individual behaviors and conditions influence overall safety outcomes, providing insights beyond aggregate data. ABM effectively models complex interactions, capturing dependencies between human behavior, machine performance, and environmental conditions, and revealing emergent patterns, such as how poor machine condition may amplify the effects of PPE non-compliance. Additionally, ABM facilitates scenario testing, allowing organizations to explore “what-if” scenarios like changes in compliance rates or maintenance schedules, which aids in planning and decision-making. The model’s ability to track risk progression over time, as shown in Figure 11, helps identify critical intervention periods, while the risk heatmap in Figure 10 highlights high-risk combinations (e.g., poor machine condition and PPE non-compliance), enabling targeted interventions. Overall, ABM provides a robust framework for proactive safety management by revealing how individual actions accumulate into system-wide outcomes, ultimately enabling organizations to implement data-driven strategies that enhance workplace safety and reduce accident risks.

Random forest

The RF model, a powerful ensemble learning method, was applied to analyze and predict incident severity by evaluating the influence of key features and assessing classification performance. Figures 12, 13, and 14 offer insights into the model’s ability to differentiate between severe and non-severe incidents, highlighting important variables and assessing predictive accuracy.

Figure 12 shows “Key Predictive Features for Accident Severity,” ranks the top 15 features contributing to the prediction of incident severity. “Primary Cause” emerges as the most influential factor, followed closely by other variables such as “Primary Cause_Availability,” “Primary Cause_Fire/Explosion,” and “Machine Condition_NMR.” The presence of both “PPE_Yes” and “PPE_No” as important features underscore the role of PPE compliance in influencing accident outcomes. These findings allow safety management teams to prioritize factors most associated with severe incidents, enabling targeted interventions on high-impact areas to mitigate risk.

RF classification outcomes for incident severity are shown in Fig. 13. This confusion matrix compares actual incident severity (Severe vs. Non-Severe) with the model’s predictions. The model correctly classifies 892 non-severe incidents and 58 Severe incidents, but it misclassifies 177 Severe incidents as non-severe and 56 non-severe incidents as Severe. This performance evaluation reveals that while the model effectively identifies non-severe cases, it faces challenges in accurately identifying Severe incidents, leading to a higher number of false negatives. This may be due to class imbalance or overlapping characteristics between the severe and non-severe categories, suggesting the need for further tuning or additional feature engineering to improve the model’s sensitivity to severe cases.

The predictive accuracy curve for the RF Model shown in Fig. 14, reflects the model’s ability to discriminate between severe and non-severe incidents across various thresholds. With an AUC score of 0.71, the model demonstrates moderate predictive accuracy, indicating it can distinguish severity levels better than random guessing, though there is room for improvement. The AUC score suggests that the model captures true positives at a reasonable rate, but further enhancements could boost its accuracy, particularly in distinguishing Severe incidents from non-severe ones.

The confusion matrix (Fig. 13) and ROC curve (Fig. 14) offer different yet complementary perspectives on the RF model’s performance, each serving distinct purposes in evaluating its classification ability. RF classification outcomes for incident severity, confusion matrix provides the model’s predictions at a specific decision threshold (typically set at 0.5), displaying the number of correct and incorrect classifications for each severity category. This metric focuses on classification accuracy at a defined threshold, highlighting areas where the model may misclassify severe cases as non-severe, which is particularly important for assessing immediate prediction reliability. In contrast, the ROC curve, the predictive accuracy curve for the RF Model, evaluates the model’s performance across all possible thresholds, offering a comprehensive view of its ability to differentiate between severe and non-severe incidents. The AUC score from the ROC curve, which is independent of any specific threshold, provides an overall measure of the model’s discriminatory power, showcasing how well it balances true positives against false positives across various cutoff points. Figures 13 and 14 emphasize their distinct roles to avoid potential confusion in interpreting these metrics, with the confusion matrix reflecting classification success at a fixed threshold and the ROC curve representing threshold-independent performance. In conclusion, the RF model shows considerable potential for classifying incident severity, with key features like primary cause, machine condition, and PPE compliance emerging as influential predictors. Although the model achieves an AUC score of 0.71, indicating moderate accuracy, there is room for improvement, particularly in reducing false negatives for severe incidents. The insights from Figs. 12, 13, and 14 underscore the importance of understanding both key predictive features and performance metrics at various thresholds, enabling organizations to make data-driven decisions to enhance safety measures by focusing on high-impact features and fine-tuning interventions to improve the model’s sensitivity to severe cases.

Survival analysis

Survival analysis, using Cox proportional hazards modeling and Kaplan–Meier survival curves, offers a comprehensive assessment of factors influencing incident risk and timing, essential for effective safety management. This approach not only identifies the likelihood of incident occurrence but also the timeframe within which incidents are likely to happen. Figures 15 and 16 illustrate this analysis by showing the hazard ratios for various covariates and the survival probability over time for different primary causes of incidents. Supplementary Table S1 gives the summary of Cox Model covariates with hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals. The Cox model in Fig. 15 quantifies the impact of individual factors, such as primary causes and compliance levels, on incident risk. A hazard ratio (HR) greater than 1 indicates an increased risk associated with a covariate, while a ratio less than 1 suggests a lower risk. For instance, “Fall from Height” and “Negligent Driving” show hazard ratios of 1.244 and 1.238, respectively, implying a heightened risk of occurrence. In contrast, factors like “Inundation”, and “Unsafe Dismantling” have hazard ratios below 1, indicating a reduced likelihood of incidents associated with these causes. Additionally, the presence of PPE-related variables in the model highlights the significant role of PPE compliance in mitigating or amplifying risk, with non-compliance markedly increasing hazard levels. The 95% confidence intervals for each hazard ratio provide insight into the precision of these estimates, with narrower intervals indicating greater reliability.

Complementing the Cox model, the Kaplan–Meier survival curves in Fig. 16 shows the time-dependent probability of incident occurrence for various causes. These curves allow for a comparison of survival rates, showing how quickly incidents are likely to manifest after certain conditions are present. For instance, “Fall from Height” exhibits a rapid drop in survival probability, reaching near zero quickly, suggesting an immediate risk requiring urgent intervention. In contrast, “Slip/Trip/Fall” and “Failure of Positive Isolation” show more gradual declines in survival probability, indicating a slower progression and potentially allowing for longer intervention timelines. Both the Cox model and Kaplan–Meier curves provide a dual perspective: hazard ratios from the Cox model help prioritize high-impact factors based on their contribution to risk, while the Kaplan–Meier curves highlight temporal patterns, allowing safety teams to identify critical windows for intervention. This combination enhances the understanding of incident dynamics, enabling data-driven decisions that allocate resources effectively and implement preventive measures tailored to specific risk factors and timelines.

Thus, survival analysis is invaluable in incident risk assessment as it not only pinpoints high-risk factors through hazard ratios but also sheds light on the timing of potential incidents via survival probabilities. By integrating both aspects, organizations can strategically plan and execute safety interventions, focusing on immediate risks like “Fall from Height” and “Negligent Driving” while managing other causes with more prolonged risk timelines. This proactive, informed approach supports improved safety outcomes by addressing both the magnitude and timing of risks.

Integrated multi-model comparison and hypothesis validation

This study proposes a comprehensive framework integrating BN, GBM/XGBoost, RF, NLP with Sentiment Analysis, ABM, and Survival Analysis to enhance predictive accuracy and generate probabilistic insights into accident causes in high-risk industries, such as the steel industry. The framework’s multi-model approach provides a multifaceted view of incident risk, supporting the hypothesis that combining these methodologies can outperform traditional single-model analyses in both prediction accuracy and causal understanding.

ML models GBM/XGBoost and RF proved effective in identifying critical risk factors, such as “Primary Cause,” “Machine Condition,” and “PPE Compliance,” which consistently appeared across feature importance analyses. Both models performed well with prevalent incident types but faced challenges with rare events due to data imbalance. The ROC curves and classification reports underscore their strength in identifying high-impact incidents while highlighting a need for class-balancing techniques to improve accuracy in low-frequency categories. The BN model complements these findings by capturing probabilistic dependencies and complex causal relationships, offering a nuanced understanding of accident causes and their interdependencies.

NLP with Sentiment Analysis provided unique value by extracting insights from unstructured incident reports, revealing sentiment patterns and recurring terminology associated with different incident causes. The sentiment distribution highlighted areas of heightened negative sentiment, indicating critical incident types that require immediate intervention. Additionally, the word clouds generated for each incident type enriched the analysis by identifying frequent terms associated with specific causes, adding qualitative depth and enhancing the contextual relevance of the quantitative models. This layer of textual data analysis supports a more comprehensive interpretation of accident causes and perceptions.

The ABM approach offered a simulation-based perspective, illustrating how interactions between workers, machines, and safety protocols contribute to accident risk. The risk heatmap generated from ABM results demonstrated the compounded effect of poor machine condition and PPE non-compliance, validating the need for integrated safety measures addressing both equipment maintenance and human compliance. The cumulative accident trend over time revealed critical intervention periods, reinforcing the hypothesis that dynamic modeling provides actionable insights into risk progression.

Survival Analysis, through Cox Proportional Hazards modeling and Kaplan–Meier survival curves, added a temporal dimension, enabling the study to model the timing of incident occurrences and assess the likelihood of incident recurrence. Hazard ratios identified key factors influencing risk, such as “Fall from Height” and “Negligent Driving,” while survival curves highlighted critical timeframes for intervention. This time-to-event analysis aligns with the study’s hypothesis, demonstrating that the integrated framework can provide proactive safety insights and guide timely preventive actions.

These models validate the hypothesis by demonstrating enhanced predictive capabilities and improved causal understanding. BN and ML models collectively balance probabilistic reasoning with pattern recognition, capturing dependencies and identifying high-impact features. NLP adds context by integrating insights from textual data, while ABM simulates behavioral and systemic dynamics, revealing intervention points in a controlled environment. Finally, Survival Analysis provides a temporal perspective, facilitating strategic planning for accident prevention.

This integrated framework not only achieves higher predictive accuracy than individual models but also bridges the gap between prediction and causation, offering a comprehensive, multi-dimensional view of accident risks. By addressing uncertainties and capturing complex causal relationships, this approach proves superior in developing robust, data-informed safety interventions. The findings have significant implications for safety management in high-risk industries, enabling safety professionals to implement effective, timely measures and fostering a safer work environment through a holistic understanding of risk factors.

Detailed Insights from Survival Analysis Survival analysis, utilizing Cox Proportional Hazards Models and Kaplan–Meier Survival Curves, provide valuable insights into the timing and likelihood of incident occurrences. The Cox model quantifies the impact of various factors, such as “Fall from Height” and “Negligent Driving,” both of which emerged as significant contributors to incident risk. Hazard ratios indicate that incidents involving these causes are associated with higher likelihoods of occurrence, guiding targeted interventions. For instance, “Fall from Height” shows a hazard ratio (HR) of 1.244, implying a 24.4% increase in risk, while “Negligent Driving” has an HR of 1.238, increasing risk by 23.8%. The 95% confidence intervals provide insights into the reliability of these estimates, adding precision to risk assessment.

Kaplan–Meier survival curves complement the Cox model by offering a visual representation of survival probabilities over time for different causes. The steep drop in survival probability for “Fall from Height” suggests that incidents involving falls tend to occur rapidly, indicating an immediate need for preventive measures. In contrast, incidents related to “Slip/Trip/Fall” show a more gradual decline, allowing for a longer intervention timeline. This temporal perspective enables organizations to prioritize high-risk factors and develop tailored strategies that address both immediate and evolving risks.

Importance of Survival Analysis in Safety Management Survival analysis plays a crucial role in understanding incident dynamics by providing insights into the timing of potential incidents and identifying high-risk factors. By quantifying hazard ratios and visualizing survival probabilities, survival analysis allows organizations to develop effective preventive strategies focused on mitigating high-risk behaviors and conditions before they lead to severe outcomes. Understanding both the magnitude and timing of risks enables safety teams to allocate resources more effectively, prioritize high-impact areas like “Fall from Height,” and manage longer-term risks associated with factors such as “Failure of Positive Isolation.”

The proposed AI framework can be effectively integrated into existing safety management systems in high-risk steel industries, enabling real-time risk assessment, predictive analytics, and proactive interventions. By leveraging BN, ML, NLP, ABM, and Survival Analysis, organizations can enhance compliance strategies, optimize safety protocols, and reduce accident rates. These findings contribute to industry-wide safety standards by promoting data-driven regulatory frameworks, ensuring continuous improvement in occupational safety and risk management.

Conclusions

The research provides a multi-model framework that integrates the various AI models like BN, ML models (GBM/XGBoost and RF), and NLP with ABM, sentiment analysis and survival analysis to augment prediction accuracy and excavate analysis of the causality of accidents for risk-prone steel industries. Every model for the multi-model framework recommends unique strengths that complement each other, justifying the hypothesis stating the outperformance of a multi-model approach contrary to conventional single method analysis for prediction and causal insights.

-

Probabilistic and Pattern Recognition BN portrays probabilistic dependencies, whereas the ML models improve at pattern recognition, recognizing connections and risk prone causal factors.

-

Contextual and Behavioral Insights NLP with Sentiment Analysis improves qualitative property through the extraction of insights from unstructured reports of incidents, that enriches interpretation of causes and sentiments. ABM simulates relationships between workers, equipment, and safety protocols, revealing the significance of compliance and machine condition in influencing risks.

-

Temporal Analysis Survival Analysis identifies the likelihood and time for the occurrence of an incident. Simultaneously with ABM, the application of survival analysis facilitates businesses to calculate critical intervals for safety intermediations.

The applications of aforesaid AI based approaches deliver a unique perspective to the realm of safety management literature for steel industry by providing a robust and dynamic model for accurately predicting accidents and proactively devising strategy for resilient control. The research limitations include that there is a need to address the projection of study findings outside the scope of referred data to similar high-risk industries. Also, validating the results of the model in a real-world setting could further enhance the applicability of the research. Potential future research the study could concentrate on an integration of real-time data sources through IoT to enable proactive risk management enhancing responsiveness of the workplace. The use of advanced tools and techniques can improve prediction accuracy for rare types of incidents. The spatial and temporal dimensions to ABM and survival analysis can reveal location specific risks trends. Further the use of automation in reporting accidents with NLP can stimulate insights for data driven safety management. The framework used in this research enhances prediction accuracy and provides a comprehensive view of incident risk, enabling safety professionals to create proactive, data-driven interventions. Key risk factors like “Primary Cause,” “Machine Condition,” and “PPE Compliance” are prioritized, allowing for focused preventive measures. The findings of this study support the notion that a multi-model AI framework enhances prediction for accident causation, outperforming conventional approaches. The AI based approach advances risk management by addressing both explicit and latent factors and considering the magnitude of risks.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ABM:

-

Agent-based modeling

- BN:

-

Bayesian networks

- GBM/XGBoost:

-

Gradient boosting machines

- ML:

-

Machine learning

- NLP:

-

Natural language processing

- RF:

-

Random forest

References

Aissani, N., Guitarni, I. H. M., & Lounis, Z. Decision process for safety based on Bayesian approach. In 2018 3rd International Conference on Pattern Analysis and Intelligent Systems (PAIS), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1109/PAIS.2018.8598533 (2018).

Zhang, X. & Mahadevan, S. Bayesian network modeling of accident investigation reports for aviation safety assessment. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 209, 107371. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ress.2020.107371 (2021).

Azeez, S., & Cranefield, J. Assimilation of major accident hazard (MAH) analysis into process safety management (PSM) process. In Paper presented at the International Petroleum Technology Conference, Doha, Qatar. https://doi.org/10.2523/IPTC-18551-MS (2015).

NRTC automation, important OSHA stats and figures in manufacturing [Online] Available: https://www.nrtcautomation.com/blog/important-osha-stats-and-figures-in-manufacturing. Accessed 05 March 2025.

Johnstone, J. & Curfew, J. Twelve steps to engineering safe onshore oil and gas facilities. Oil Gas Fac. 1, 38–46. https://doi.org/10.2118/141974-PA (2012).

Zheng, X. & Liu, M. An overview of accident forecasting methodologies. J. Loss Prev. Process Ind. 22(4), 484–491. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jlp.2009.03.005 (2009).

Gnoni, M. G. & Saleh, J. H. Near-miss management systems and observability-in-depth: Handling safety incidents and accident precursors in light of safety principles. Saf. Sci. 91, 154–167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2016.08.012 (2016).

Hannaman, G. & Worledge, D. Some developments in human reliability analysis approaches and tools. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 22(1–4), 235–256. https://doi.org/10.1016/0951-8320(88)90076-2 (1987).

Etherton, J. R. Industrial machine systems risk assessment: A critical review of concepts and methods. Risk Anal. 27(1), 71–82. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1539-6924.2006.00860.x (2007).

Rao, A. H., Yu, M. & Sasangohar, F. Towards harmonizing safety databases: An assessment of existing data Sources. Proc. Human Factors Ergon. Soc. Ann. Meet. https://doi.org/10.1177/1071181319631250 (2019).

Benner, L. Accident investigation data: Users’ unrecognized challenges. Saf. Sci. 118, 309–315. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2019.05.021 (2019).

Shlayan, N., Kachroo, P., & Wadoo, S. Bayesian Safety analyzer using multiple data sources of accidents. In 2011 14th International IEEE Conference on Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITSC), Washington, DC, USA, 2011 151–156, https://doi.org/10.1109/ITSC.2011.6083122.

Carrodano, C. Data-driven risk analysis of nonlinear factor interactions in road safety using Bayesian networks. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-69740-6 (2024).

Liao, H., Li, Y., Wang, C., Guan, Y., Tam, K., Tian, C., & Li, Z. (2024). When, Where, and What? A benchmark for accident anticipation and localization with large language models. In Proceedings of the 32nd ACM International Conference on Multimedia 8–17.

Maceiras, C., Cao-Feijóo, G., Pérez-Canosa, J. M. & Orosa, J. A. Application of machine learning in the identification and prediction of maritime accident factors. Appl. Sci. 14(16), 7239. https://doi.org/10.3390/app14167239 (2024).

Mihaljević, B., Bielza, C. & Larrañaga, P. Bayesian networks for interpretable machine learning and optimization. Neurocomputing 456, 648–665. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neucom.2021.01.138 (2021).

Ma, Z., Mei, G. & Cuomo, S. An analytic framework using deep learning for prediction of traffic accident injury severity based on contributing factors. Accid. Anal. Prev. 160, 106322. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aap.2021.106322 (2021).

Borjalilu, N. Risk assessment and machine learning models. IntechOpen https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.1005485 (2024).

Kamil, M. Z., Khan, F., Amyotte, P. & Ahmed, S. Multi-source heterogeneous data integration for incident likelihood analysis. Comput. Chem. Eng. 185, 108677 (2024).

Lacherre, J., Castillo-Sequera, J. L. & Mauricio, D. Factors, prediction, and explainability of vehicle accident risk due to driving behavior through machine learning: A systematic literature review, 2013–2023. Computation 12(7), 131. https://doi.org/10.3390/computation12070131 (2024).

Ziegler Haselein, B., Da Silva, J. C. & Hooey, B. L. Multiple machine learning modeling on near mid-air collisions: An approach towards probabilistic reasoning. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 244, 109915. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ress.2023.109915 (2024).

Munim, Z. H., Sørli, M. A., Kim, H. & Alon, I. Predicting maritime accident risk using automated machine learning. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 248, 110148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ress.2024.110148 (2024).

Ahmed, S., Hossain, M. A., Ray, S. K., Bhuiyan, M. M. I. & Sabuj, S. R. A study on road accident prediction and contributing factors using explainable machine learning models: Analysis and performance. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 19, 100814. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trip.2023.100814 (2023).

Gao, X. et al. Uncertainty-aware probabilistic graph neural networks for road-level traffic crash prediction. Accid. Anal. Prev. 208, 107801. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aap.2024.107801 (2024).

Fahad, K., Joarder, M. F., Nahid, M., Tasnim, T. Road accidents severity prediction using a voting-based ensemble ML model. In International Conference on Big Data, IoT and Machine Learning 793–808. (Springer, Singapore).

Kandel, R. & Baroud, H. A data-driven risk assessment of Arctic maritime incidents: Using machine learning to predict incident types and identify risk factors. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 243, 109779. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ress.2023.109779 (2024).

Wu, L., Mohamed, E., Jafari, P. & AbouRizk, S. Machine learning–based Bayesian framework for interval estimate of unsafe-event prediction in construction. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 149(11), 04023118. https://doi.org/10.1061/JCEMD4.COENG-13549 (2023).

Ramadan, I & Salim, M. Development of machine learning classification models for predicting unrecorded traffic accidents. Available SSRN 4706223. Accessed 04 November 2024. [Online]. Available: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4706223

Zhang, J., Jin, M., Wan, C., Dong, Z. & Wu, X. A Bayesian network-based model for risk modeling and scenario deduction of collision accidents of inland intelligent ships. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 243, 109816. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ress.2023.109816 (2024).

Priyanka, S., Jayadharshini, P., Santhiya, S.,Divyadharshini, B., Samyuktha, K. & Madan, P. Machine learning applications in traffic safety: Assessing accident severity automatically. In 2023 7th International Conference on Electronics, Communication and Aerospace Technology (ICECA), Coimbatore, India, 1197–1203, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICECA58529.2023.10394978. (2023).

Xie, X. et al. Risk prediction and factors risk analysis based on IFOA-GRNN and apriori algorithms: Application of artificial intelligence in accident prevention. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 122, 169–184 (2019).

Sarkar, S., Vinay, S., Raj, R., Maiti, J. & Mitra, P. Application of optimized machine learning techniques for prediction of occupational accidents. Comput. Oper. Res. 106, 210–224 (2019).

Sattari, F., Macciotta, R., Kurian, D. & Lefsrud, L. Application of Bayesian network and artificial intelligence to reduce accident/incident rates in oil & gas companies. Saf. Sci. 133, 104981 (2021).

Acknowledgements

The research scholar Mr. Shatrudhan Pandey sincerely thanks Department of Production and Industrial Engineering, Birla Institute of Technology, Mesra, Ranchi, India, for awarding an Institute Research Fellowship (GO/Estb/Ph.D/IRF/2020-21/2484A). This fellowship has played a crucial role in supporting and advancing the scholarly endeavors of the researchers involved in this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: Shatrudhan Pandey, Abhishek Kumar Singh, Shreyanshu Parhi, Sanjay Kumar Jha; Data curation: Shatrudhan Pandey; Formal Analysis: Shatrudhan Pandey.; Investigation: Shatrudhan Pandey; Methodology: Shatrudhan Pandey, Abhishek Kumar Singh, Shreyanshu Parhi, Sanjay Kumar Jha; Project administration: Abhishek Kumar Singh, Shreyanshu Parhi.; Resources: Shatrudhan Pandey.; Software: Shatrudhan Pandey.; Supervision: Abhishek Kumar Singh, Shreyanshu Parhi.; Validation: Abhishek Kumar Singh, Shatrudhan Pandey Visualization: Abhishek Kumar Singh, Shatrudhan Pandey.; Writing–original draft: Shatrudhan Pandey, Abhishek Kumar Singh, Shreyanshu Parhi; Writing–review & editing: Shatrudhan Pandey, Abhishek Kumar Singh, Shreyanshu Parhi, Sanjay Kumar Jha.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pandey, S., Singh, A.K., Parhi, S. et al. Towards safer steel operations with a multi model framework for accident prediction and risk assessment simulation. Sci Rep 15, 13293 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96028-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96028-0