Abstract

In order to enhance the sustainable development of the agroforestry system, this work explored the allelopathic effects between two medicinal plants. Siraitia grosvenorii was selected as the recipient plant and investigated the allelopathic effects of different concentrations of fig tree (Ficus carica L.) stem aqueous extracts on seed germination, seedling growth, and physiological indicators of S. grosvenorii through simulated rainfall and fogging pathways, exploring whether the two medicinal plants are suitable for integrated planting management. It found that the low concentration of fig tree stem (Ficus carica L.) stem aqueous extracts (5.0–10.0 g/L) not only promoted the seed of another medicinal plant S. grosvenorii, but also significantly improved its biomass and photosynthetic parameters. However, with the increase of the concentration of fig tree stem aqueous extracts (15.0–25.0 g/L), the activities of superoxide dismutase and peroxidase of S. grosvenorii first increased and then decreased, and the content of malondialdehyde increased. The synthetic allelopathy index of S. grosvenorii showed a pattern of first increase and then inhibition. It indicated that there is a certain allelopathic relationship between the two medicinal plants, making them suitable for intercropping in the agroforestry system.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As a common management practice in forest ecosystems, the agroforestry system of medicinal plants is considered a sustainable development model. By planting high-quality medicinal plants locally and utilizing the land and water resources in the forest clearing, a single forest land can be transformed into a complex ecosystem with multiple functions and structures1,2. The medicinal agroforestry system has a higher capacity to absorb and utilize the light energy, water, and nutrients required for growth compared to single land-use systems, thereby further improving land use yield and land production efficiency3. Medicinal plant intercropping systems enhance land-use efficiency and reduce pest transmission, yet their success requires precise allelopathic regulation4.

Allelopathy refers to the phenomenon where plants release certain allelochemicals that affect the growth and development of neighboring plants5,6. Allelopathic plants release these compounds into the surrounding atmosphere and soil through volatilization, leaf leaching, root exudation, and residue decomposition, promoting or inhibiting plant growth through interspecific interactions, and altering crop-weed plant communities7,8. Utilizing the stimulatory/inhibitory effects of allelochemicals on plant growth and development, while avoiding autotoxicity in cultivation systems, is crucial for long-term agricultural development9. Recent studies have revealed significant concentration-dependent effects of allelochemicals. For instance, phenolic compounds act as signaling molecules to enhance antioxidant defenses in recipient plants at low concentrations (<5 µM), while inducing reactive oxygen species (ROS) burst and membrane lipid peroxidation at high concentrations (>20 µM)10,11. Meanwhile, moisture levels significantly influence allelochemical secretion, as water stress can enhance the production of phenolic compounds in Phytoecia species. Similarly, temperature fluctuations during plant developmental stages may modulate the degradation rate of allelopathic substances, affecting their efficacy. Seedling stages exhibit greater tolerance to allelopathy compared to mature plants, likely due to reduced metabolic activity and resource allocation. It suggests that allelopathic effects may extend beyond traditional inhibitory roles. Therefore, in order to establish harmonious relationships between species in the medicinal agroforestry system, it is necessary to conduct in-depth research on allelopathic effects within the medicinal agroforestry system.

Siraitia grosvenorii (Swingle) C. Jeffrey (S. grosvenorii) is a perennial vine native to China, belonging to the Cucurbitaceae family of plants12. The main active ingredient of S. grosvenorii is mogrosides (Mog), which account for approximately 3.8% of its content. Mogrosides are triterpene glycosides and are part of the cucurbitane class of compounds13,14, including Mog III, Mog IV, Mog V, Mog VI, etc. Among them, Mog V is the main sweet component. Studies have shown that extracts from S. grosvenorii have beneficial properties, such as antioxidant15, antitumor16, anti-inflammatory17, antifibrotic effects18, etc.

The fig tree (Ficus carica L.) is a fig plant of the Moraceae family, a highyielding traditional medicinal plant with antitumor, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-fatigue, and anticancer properties19,20. Studies have shown that after inter-cropping with fig trees, the growth rate and net photosynthetic rate of Taxus cuspidata significantly improved, promoting the growth of both plants21. Planting medicinal plants under the forest canopy increases the nutritional content of the soil, enhances the rhizosphere microbial communities of other plants, strengthens the ability of microbes to utilize soil carbon sources, increases the number of dominant microbes, and enriches other species, thus having a positive impact on the soil environment22. Therefore, further research on the composite planting of medicinal plants can more effectively utilize land resources and reduce the use of pesticides and fertilizers23.

The promotive or inhibitory effects of two medicinal plants are key to the medicinal agroforestry system. The medicinal agroforestry system is a multifunctional production system for medicinal plants, which, compared to monoculture practices, is a more beneficial land use practice that helps improve soil quality and soil biodiversity24,25. The medicinal agroforestry system not only promotes ecological diversity and sustainability, but also provides social, economic, and environmental benefits.

In this work, S. grosvenorii was selected as the recipient plant and investigated the allelopathic effects of different concentrations of fig tree (Ficus carica L.) stem aqueous extracts on seed germination, seedling growth, and physiological indicators of S. grosvenorii through simulated rainfall and fogging pathways. The allelopathy of fig stem extracts on the medicinal plant Siraitia grosvenorii was systematically evaluated for the first time, focusing on the concentration dependent physiological regulation mechanism, which provided new insights for plant interaction in the agroforestry system.

Results

The impact of fig tree stem water extract on the germination of S. grosvenorii seeds

Under various concentrations of fig tree stem aqueous extract, the germination rate (GR) of S. grosvenorii varies, with the E10.0 concentration reaching the maximum value for GR. The GR of S. grosvenorii decreases with the increasing concentration of the fig tree stem aqueous extract, and high concentrations of the fig tree stem aqueous extract result in significantly lower GR, GP, GI, and SVI values for S. grosvenorii compared to the control (Table 1). All values represent the mean ± SD.

The impact of fig tree stem aqueous extract on the growth of S. grosvenorii seedlings

The dry weight of S. grosvenorii seedlings varies with the concentration of the fig tree stem aqueous extract. The E10.0 treatment with the fig stem aqueous extract showed a better promotional effect on the plant’s overground part weight (OPW), underground part weight (UPW), and total part weight (TPW). The OPW, UPW, and TPW reached their peak values at E10.0. The OPW, UPW, and TPW at concentrations higher than E10.0 were significantly lower than the control, and the indicators showed a decreasing trend with the increase in extract concentration (Table 2). All values represent the mean±SD.

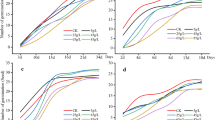

The impact of fig tree stem aqueous extract on the photosynthesis of S. grosvenorii

With the increase in the concentration of the fig stem aqueous extract, the Pn, Tr, Gs, and Ci of S. grosvenorii show a trend of initially increasing and then slowly declining. The E10.0 treatment with the fig stem aqueous extract has a strong promoting effect on the Pn, Tr, Gs, and Ci of S. grosvenoriii (Fig. 1). The contents of Chla (chlorophyll a), Chlb (chlorophyll b), and Chl (total chlorophyll) in S. grosvenorii increase at E10.0 and reach their peak at E10.0, then slowly decrease as the concentration of the extract increases (Fig. 2). All values represent the mean ± SD.

Effect of fig tree stem aqueous extract on (a) Pn, (b) Ci, (c) Tr and (d) Gs of S. grosvenorii. Values are reported as mean ± SD, n = 3. CK, 0.0 g/L; E5.0, 5.0 g/L; E10.0, 10.0 g/L; E15.0, 15.0 g/L; E20.0, 20.0 g/L; E25.0, 25.0 g/L. Lowercase letters represent significant differences in each treatment group (p < 0.05). Incorporating error bars for standard deviation.

Effect of fig tree stem aqueous extract on the content of (a) chlorophyll a, (b) chlorophyll b and (c) total chlorophyll of S. grosvenorii. Values are reported as mean ± SD, n = 3. CK, 0.0 g/L; E5.0, 5.0 g/L; E10.0, 10.0 g/L; E15.0, 15.0 g/L; E20.0, 20.0 g/L; E25.0, 25.0 g/L. Lowercase letters represent significant differences in each treatment group (p < 0.05). Incorporating error bars for standard deviation.

As the concentration of the fig tree stem aqueous extract increases, the activity of SOD (superoxide dismutase) in S. grosvenorii continues to rise. When the concentration of the fig tree stem aqueous extract is E10.0, the content of SOD in S. grosvenorii is significantly higher than that of the control. SOD activity peaked in the 10.0 g/L treatment group, indicating ROS scavenging activation under mild stress26. With the increase in the concentration of the fig tree stem aqueous extract, the activity of POD (peroxidase) in S. grosvenorii shows a trend of increasing first and then decreasing, reaching its maximum value at E10.0. As the concentration of the fig tree stem aqueous extract increases, the content of malondialdehyde (MDA) in S. grosvenorii shows an upward trend. At E25.0, the content of MDA in S. grosvenorii reaches its maximum value (Fig. 3). All values represent the mean ± SD.

Effect of fig tree stem aqueous extract on (a) SOD, (b) MDA and (c) POD content of S. grosvenorii. Values are reported as mean ± SD, n = 3. CK, 0.0 g/L; E5.0, 5.0 g/L; E10.0, 10.0 g/L; E15.0, 15.0 g/L; E20.0, 20.0 g/L; E25.0, 25.0 g/L. Lowercase letters represent significant differences in each treatment group(p < 0.05). Incorporating error bars for standard deviation.

The allelopathic effect of fig tree stem aqueous extract on S. grosvenorii

Using the five indicators of GR (Germination Rate), GP (Germination Percentage), GI (Germination Index), SVI (Seedling Vigor Index), and TPW (Total Part Weight) to examine the comprehensive allelopathic effect (SE) value, we can infer the overall allelopathic effect intensity of different concentrations of fig tree stem aqueous extracts on S. grosvenorii (Fig. 4). All values represent the mean±SD. When the concentration of the fig tree stem aqueous extract is E5.0 and E10.0, it promotes the growth of S. grosvenorii, with the maximum value of SE being 0.034 at E10.0. Except for the concentrations E5.0 and E10.0, all other concentrations showed negative SE values, demonstrating an inhibitory effect on S. grosvenorii.

Allelopathic effects of fig tree stem aqueous extracts at different concentrations on S. grosvenorii. SE was calculated as the average allelopathic index (RI) of all indicators with each treatment of S. grosvenorii. Values are reported as mean ± SD, n = 3. CK, 0.0 g/L; E5.0, 5.0 g/L; E10.0, 10.0 g/L; E15.0, 15.0 g/L; E20.0, 20.0 g/L; E25.0, 25.0 g/L. Lowercase letters represent significant differences in each treatment group (p < 0.05). Incorporating error bars for standard deviation.

Discussion

Medicinal plants are widely used in the pharmaceutical and food industries due to their medicinal value, making their high-yield cultivation extremely important27. The fig tree is a well-known plant that is both medicinal and edible. This work seeks to find suitable medicinal plants to intercrop with fig trees to promote seed germination and seedling growth. Allelopathy is a ubiquitous ecological mechanism in nature and is an important factor affecting seed germination and seedling growth. The aqueous extract of fig tree stems has varying degrees of promotion or inhibition on the germination of S. grosvenorii seeds. The higher the concentration of the extract, the stronger its inhibitory effect on the germination of recipient plant seeds, which is consistent with previously reported trends28. It has been reported that allelochemicals at low concentrations have a promoting effect on plant growth and at high concentrations have a strong inhibitory effect on plant growth29,30,31. The aqueous extract of the stems of fig trees in low concentrations has a good promoting effect on the germination of the S. grosvenorii seeds, which can be attributed to increased osmotic pressure in the recipient plant cells and stimulation of respiratory enzyme activity in the cells, thus increasing the cell’s water absorption capacity and improving the plant’s ability to produce nutrients32.

The changes in the dry weight of S. grosvenorii seedlings are related to their stimulation of growth. When the concentration of fig tree stem aqueous extracts is the highest (E25.0), the reduction in OPW, UPW, and TPW are the greatest. The differences in weight can be attributed to varying allelopathic forces, which are caused by the structural variability of allelochemical compounds33. In this work, we speculate that the high concentration of allelochemicals in fig tree stem aqueous extracts reduced the photosynthetic activity of S. grosvenorii seedlings, leading to a decline in OPW, UPW, and TPW. At lower concentrations E5.0 and E10.0, there is a promoting effect on seven parameters (Pn, Tr, Gs, Ci, Chla, Chlb, and Chl), which can be attributed to the relatively mild allelopathic inhibition at lower concentrations7. As the concentration of fig tree stem aqueous extracts increases, so does the content of allelochemicals, enhancing the inhibitory effect. This indicates that the allelochemicals in fig tree stem aqueous extracts have a significant inhibitory effect on photosynthesis in plant cells, suppressing the formation of Chl (chlorophyll), thereby reducing the photosynthetic rate and oxygen uptake capacity of the recipient plants, such as Pn, Tr, Gs, and Ci34,35.

Developmental stages critically influence allelopathic sensitivity. While 3-leaf-stage seedlings were used here, preliminary data show 40% lower phenolic tolerance thresholds during S. grosvenorii flowering. This parallels findings in Salvia miltiorrhiza36, necessitating growth stage-specific management strategies. The increase in POD under 10.0 g/L treatments aligns with the ecological agriculture principle of ’moderate stress enhancing secondary metabolites’22. As the concentration of fig tree stem aqueous extracts increases, the activities of SOD and POD in S. grosvenorii seedlings first increase and then decrease, while the content of MDA gradually increases. This indicates that the plants have experienced allelopathic stress from the extracts, leading to an overproduction of reactive oxygen species (ROS), thereby increasing the activity of antioxidant enzymes to maintain basic physiological metabolism37. However, the regulatory capacity of the antioxidant enzyme system is only temporary and limited. When high concentrations of allelochemicals cause the accumulation of oxidative products to exceed their threshold, enzyme activity will be impaired, POD activity will decrease, and the content of MDA will increase38. Analogous to juglone’s allelo-pathic effects on Medicago truncatula39, the sharp MDA increased in >15.0 g/L treatments suggests membrane system damage as a key growth inhibition mechanism. The synthesized allelopathy index can fully express the intensity of allelopathy measured in S. grosvenorii. Studies have shown that many plants, such as walnut and alfalfa, produce allelochemicals like phenolic compounds or autotoxic phenomena, which have a highly inhibitory effect on the germination and seedling growth of various cultivated or wild-growing plants39,40. In this work, fig tree stem aqueous extracts at low concentrations (E5.0–E10.0) can promote the growth of S. grosvenorii. This is mainly attributed to the allelochemicals in the fig tree stem aqueous extracts, which may be released into the soil environment through rain and fog, promoting the formation of mycorrhizae, and directly or indirectly promoting the growth of S. grosvenorii. From an ecological perspective, fig stem extracts may indirectly influence nutrient cycling by modulating soil microbial communities. For example, low-concentration phenolics can stimulate phosphate-solubilizing bacteria activity41, aligning with biomass increases observed in 10.0 g/L treatments. However, controlled conditions cannot replicate field-level biotic interactions, necessitating future metagenomic investigations of rhizosphere microbial mediation. Notably, environmental factors like temperature and moisture were not considered. Recent work demonstrates drought stress significantly increases flavonoid glycoside content in fig leaves42, highlighting the need for climate-data-integrated field monitoring. While experiments were conducted under subtropical monsoon climate (mean annual temperature: 18.5 °C), S. grosvenorii cultivation spans central subtropical to northern tropical zones. Follow-up multi-site trials in Guangxi (24°N) and Yunnan (25°N) are recommended.

Materials and methods

Plant materials

The stems of the fig tree and the seeds of S. grosvenorii were collected from the experimental fields in Ziyuan County, Guilin City, Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, China (25°48’ N; 110°13’ E). The region belongs to the subtropical monsoon climate zone, with an average annual temperature of around 16.7 °C; the average annual sunshine duration is 1275 h, and the average annual rainfall is 1736 mm. The control group received the same volume of distilled water as treatment groups to ensure comparable soil moisture conditions. All soils were sterilized at 121 °C for 30 min to eliminate indigenous microbial interference.

Preparation of fig tree stem aqueous extract

The fig tree stems were air-dried at room temperature for 48 h, then fermented in a blender and passed through an 80-mesh sieve to create a fine powder. The fig stem powder samples (5 g) were mixed with 200 mL of distilled water and continuously agitated at 25°C for 24 h. After mixing with the residue, the mixture was filtered twice to obtain an aqueous extract with a concentration of 25 g/L. Extracts with concentrations of 0.0, 5.0, 10.0, 15.0, 20.0, and 25.0 g/L were prepared using this method and stored at 4°C before use. Total phenolic content was qualitatively determined using the Folin–Ciocalteu method43, while terpenoids were preliminarily identified via thin-layer chromatography (TLC) (mobile phase: chloroform-methanol = 9:1). Results showed phenolic compounds constituted 68.2 ± 3.5% of extracts, consistent with prior studies on Ficus carica secondary metabolites44. The concentration gradient (5.0–25.0 g/L) was determined based on preliminary experiments: seed germination rates dropped below 15% of controls at > 25.0 g/L, while no significant allelopathic effects were observed at < 5.0 g/L.

Seed germination experiment

The S. grosvenorii seeds were soaked in a 5% sodium hypochlorite solution for 3 minutes for disinfection and sterilization, then rinsed with distilled water at least 3 times and air-dried at room temperature. Two layers of filter paper were placed in sterile petri dishes (90 mm), and three replicates were prepared for each treatment, with 50 seeds per replicate. To each clearly labeled petri dish, 10 mL of fig stem aqueous extract of different concentrations was added. The control group was given 10 mL of deionized water. S. grosvenorii seeds were treated with 0.0 g/L, 5.0 g/L, 10.0 g/L, 15.0 g/L, 20.0 g/L, and 25.0 g/L, respectively. All experiments were repeated three times. All clearly labeled petri dishes were placed in an incubator set at a constant temperature of 25 ± 1 ℃, 70% humidity, and a photoperiod of 12 h. Recording the number of germinated S. grosvenorii seeds daily and added the corresponding treatment liquid every 24 h to keep the petri dishes moist.

After the seeds germinated, if there was no further germination for three consecutive days, the germination test was considered complete. To detect the impact of the fig stem aqueous extract on the seed germination process, the following indices were tested: Germination Rate (GR), Germination Potential (GP), Germination Index (GI), and Seedling Vigor Index (SVI). The indices were calculated using the following formulas45:

Gt: the number of germinated seeds per day corresponding to Dt. Dt: the number of germination days.

Seedling vigor index (SVI) = Germination rate Seedling weight.

Potted plant experiment

To further verify the results of the indoor experiments, a potted plant growth experiment was conducted using fig tree stem aqueous extracts on S. grosvenorii seedlings. The potted plant experiment was carried out in the greenhouse of Guilin Normal College on April 25, 2023. Each pot was filled with 6 kilograms of soil, with an upper mouth diameter of 20 cm, a lower mouth diameter of 18 cm, and a height of 25 cm. The stems of the fig tree and the seeds of S. grosvenorii were collected from the experimental fields in Ziyuan County. The soil was collected from the experimental fields in Ziyuan County. S. grosvenorii seeds were sown in the flowerpots, with 30 seeds per pot. After 12 days of growth, each pot was thinned to 3 seedlings of similar height. The potted plant experiment was conducted from May 4, 2023, to June 12, 2024, lasting for 40 days, with a total of 72 pots of S. grosvenorii medicinal plants. During the seedling growth process, they were randomly divided into 6 treatment groups. Each treatment group was given different concentrations of fig tree stem aqueous extracts (0.0 g/L, 5.0 g/L, 10.0 g/L, 15.0 g/L, 20.0 g/L, 25.0 g/L). There were 12 replicates for each experimental group. The changes in aboveground and belowground biomass at different periods (10, 20, 30, and 40 days) were measured. After 40 days, photosynthetic indices and antioxidant enzyme activities and other physiological indicators of each treatment group were measured. Every three days, 100 mL of fig tree stem aqueous extract was irrigated into each pot, with additional water supplied as needed based on soil moisture conditions. When measuring plant biomass, three pots of S. grosvenorii medicinal plants were randomly selected from each treatment group, carefully washed with water to remove debris, and the aboveground and underground parts were separated accordingly. The dry weights of the overground parts weight (OPW) and underground parts weight (UPW) of the seedlings were measured using a precision balance after drying at 80 °C until a constant weight was achieved. A portable photosynthesis meter HD-GH10 was used to measure the net photosynthetic rate (Pn), transpiration rate (Tr), stomatal conductance (Gs), and intercellular CO2 concentration (Ci) of S. grosvenorii under clear weather conditions between 09:00 and 11:00. Measurements were repeated until a stable reading was obtained.

The physiological and biochemical characteristics of S. grosvenorii seedlings were studied. The contents of chlorophyll a (Chla), chlorophyll b (Chlb), and total chlorophyll (Chl) in the plant leaves were determined using a spectrophotometric method46. The activity of superoxide dismutase (SOD) was detected by measuring the ability of the solution to inhibit the photochemical reduction of nitroblue tetrazolium (NBT)47, while the activity of peroxidase (POD) was detected using the guaiacol method48. The content of malondialdehyde (MDA) was assayed using the 2-thiobarbituric acid (TBA) colorimetric method49.

Comprehensive allelopathic effect index

The comprehensive allelopathic effect is detected by calculating the arithmetic mean of the reaction indices of the allelopathic effect (RI) values for the same several receptor measurement test items31.

T: treatment, C: control.

When RI > 0, it means there is a promotion effect; when RI<0, it means there is an inhibitory effect.

Statistical analysis

All experiments were conducted using a completely randomized design, with each experiment repeated three times to obtain the corresponding data. Data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA in SPSS 26.0, with Duncan’s multiple range test (α = 0.05) for post-hoc comparisons. All values represent mean ± SD. Graphs were created using Origin Pro 2021.

Conclusions

This work, conducted under controlled indoor experimental conditions, examined the effects of various concentrations of fig tree stem aqueous extracts on the germination, morphology, and physiological and biochemical indicators of S. grosvenorii seedlings. The differences observed reflected the varying intensities of allelopathic effects of the fig tree on S. grosvenorii and provided insights into the impact of intercropping fig tree stem aqueous extracts with S. grosvenorii on the growth of both plants. The results indicated that the aqueous extracts of fig tree stems at low concentrations had the most promising effect on the growth promotion of S. grosvenorii. Based on concentration-dependent effects, we recommend applying fig stem extracts at less 10.0 g/L (dry weight basis) in S. grosvenorii-F. carica intercropping systems, avoiding more 15.0 g/L treatments during seedling stages. Against the backdrop of forest medicine, S. grosvenorii is suitable for intercropping with fig trees as a medicinal plant. This work offers a solid theoretical foundation for the development of future medicinal agroforestry systems and provides a new perspective for the construction of the medicinal agricultural and forestry industry system.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript.

References

Chen, H. Y. et al. Effects of fertilizer application intensity on carbon accumulation and greenhouse gas emissions in moso bamboo forest-polygonatum cyrtonema hua agroforestry systems. Plants. 13, 1941–1964. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants13141941 (2024).

Kaba, J. S., Yamoah, F. A. & Acquaye, A. Towards sustainable agroforestry management: Harnessing the nutritional soil value through cocoa mix waste. Waste Manag. 124, 264–272. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2021.02.021 (2021).

Sehgal, S. Growth and productivity of ocimum basilicum influenced by the application of organic manures under leucaena leucocephala hedgerows in western himalayan mid hills. Range Manag. Agrofor. 32, 83–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agrformet.2011.06.001 (2011).

Yang, L., Li, J., Xiao, Y. & Zhou, G. Early bolting, yield, and quality of angelica sinensis (oliv.) diels responses to intercropping patterns. Plants (Basel) 11, 2950. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants11212950 (2022).

Akhtar, N., Shadab, M., Bhatti, N., Sajid Ansarì, M. & Siddiqui, M. B. Biotechnological frontiers in harnessing allelopathy for sustainable crop production. Funct. Integr. Genomics. 24, 155. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10142-024-01418-8 (2024).

Akhtar, N., Shadab, M., Bhatti, N., Sajid Ansarì, M. & Siddiqui, M. B. Biotechnological frontiers in harnessing allelopathy for sustainable crop production. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 27, 483–495. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12298-021-00962-y (2021).

Zuo, X. et al. Allelopathic effects of amomum villosum lour. volatiles from different organs on selected plant species and soil microbiota. Plants. 11, 3550–3565. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants11243550 (2022).

Xie, M. Y. & Wang, X. R. Allelopathic effects of thuidium kanedae on four urban spontaneous plants. Sci. Rep. 14, 14794–14808. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-65660-7 (2024).

Kumar, N. et al. Allelopathic effects of amomum villosum lour. volatiles from different organs on selected plant species and soil microbiota. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants. 30, 3550–3565. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12298-024-01440-x (2024).

Qureshi, H. & Anwar, T. Role of allelopathy in invasion of invasive species. Allelopathy J. 62, 115–138. https://doi.org/10.26651/allelo.j/2024-62-2-1490 (2024).

Qureshi, H. et al. Allelopathic effects of invasive plants (lantana camara and broussonetia papyrifera) extracts: implications for agriculture and environmental management. Allelopathy J. 61, 175–187. https://doi.org/10.26651/allelo.j/2024-61-2-1478 (2024).

Huang, H. X. et al. Allelopathic effects of amomum villosum lour. volatiles from different organs on selected plant species and soil microbiota. Front. Pharmacol. 15, 1388747–1388782. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2024.1388747 (2024).

Jiang, J. L., Liang, J. & Yang, Y. Y. Research progress on pharmacological and toxicological effects of mogroside. Mod. Prev. Med. 47, 2246–2248 https://doi.org/10.20043/j.cnki.mpm.2020.12.034 (2020).

Wei, B. Q., Gao, X. Y., Liu, Y. X., Xu, H. M. & Wang, Y. C. Research progress on function and application of mogroside. Sci. Technol. Food Ind. 44, 434–441. https://doi.org/10.13386/j.issn1002-0306.2022070323 (2023).

Zhu, Y. M. et al. Chemical structure and antioxidant activity of a polysaccharide from siraitia grosvenorii. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 165, 1900–1910. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.10.127 (2020).

Haung, R., Saji, A., Choudhury, M. & Konno, S. Potential anticancer effect of bioactive extract of monk fruit (siraitia grosvenori) on human prostate and bladder cancer cells. J. Cancer Ther. 14, 211–224. https://doi.org/10.4236/jct.2023.145019 (2023).

Liu, Y. et al. The liver metabolic features of mogrosidev compared to siraitia grosvenorii fruit extract in allergic pneumonia mice. Mol. Immunol. 145, 80–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molimm.2022.03.008 (2022).

Liu, B. et al. Natural product mogrol attenuates bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis development through promoting ampk activation. J. Funct. Foods. 77, 104280. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jff.2020.104280 (2021).

Hashemi, S. A. et al. The effect of fig tree latex (ficus carica) on stomach cancer line. Iran Red Crescent Med J 13, 272–275 (2011).

Zhao, J. Y. et al. Immunomodulatory effects of fermented fig (Ficus carica L.) fruit extracts on cyclophosphamide-treated mice. J. Funct. Foods 75, 104219. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jff.2020.104219 (2020).

Yang, X. et al. Enhancement of interplanting of ficus carica l with taxus cuspidata sieb. et zucc. on growth of two plants. Agriculture 11, 1276–1290. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture11121276 (2021).

Yu, Y. et al. The compound forest–medicinal plant system enhances soil carbon utilization. Forests 14, 1233–1251. https://doi.org/10.3390/f14061233 (2023).

Peng, X. B., Zhang, Y. Y., Cai, J., Jiang, Z. M. & Zhang, S. X. Photosynthesis, growth and yield of soybean and maize in a tree-based agroforestry intercropping system on the loess plateau. Agrofor. Syst. 76, 569–577. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10457-009-9227-9 (2009).

Pala, N. A. Soil microbial characteristics in sub-tropical agro-ecosystems of north western himalaya. Curr. Sci. 115, 1956–1959. https://doi.org/10.18520/cs/v115/i10/1956-1959 (2018).

Seid, G. & Kebebew, Z. Homegarden and coffee agroforestry systems plant species diversity and composition in yayu biosphere reserve, southwest ethiopia. Heliyon. 20, 09281–09290. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e09281 (2022).

Abisha, C., Christian, O., Amitava, M., Seid, G. & Kebebew, Z. Eco-corona formation diminishes the cytogenotoxicity of graphene oxide on allium cepa: role of soil extracted-extracellular polymeric substances in combating oxidative stress. Plant Physiol. Biochem.: PPB. 204, 108123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plaphy.2023.108123 (2023).

Fatemeh, J. K., Zahra, L. & Hossein, A. K. Medicinal plants: past history and future perspective. J. Herbmed. Pharmacol. 7, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.15171/jhp.2018.01 (2018).

Abbas, A., Huang, P., Hussain, S., Saqib, M. & Du, D. Application of allelopathic phenomena to enhance growth and production of camelina (camelina sativa (l)). Appl. Ecol. Environ Res 19, 453–469. https://doi.org/10.15666/aeer/1901453469 (2019).

You, X., Xin, C., Le, D. & ChuiHua, K. Allelopathy and allelochemicals in grasslands and forests. Forests 14, 562. https://doi.org/10.3390/f14030562 (2023).

Fan, L. H. et al. The allelopathy effect of artemisia scoparia water extracts on grassland plants seed germination. Chin. J. Grassland. 43, 96–103. https://doi.org/10.16742/j.zgcdxb.20190297 (2021).

Alemayehu, Y., Chimdesa, M., Yusuf, Z.: Allelopathic effects of lantana camara l. leaf aqueous extracts on germination and seedling growth of capsicum annuum l. and daucus carota l. Scientifica (Cairo). 2024, 9557081–9557090 (2024) https://doi.org/10.1155/2024/9557081

Batish, D. R., Singh, H. P. & Kaur, S. Crop allelopathy and its role in ecological agriculture. J. Crops Prod. 4, 121–161. https://doi.org/10.1300/J144v04n0203 (2001).

Gniazdowska, A. & Bogatek, R. Allelopathic interactions between plants. Multisite action of allelochemicals. Acta Physiol. Plant. 27, 395–407. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11738-005-0017-3 (2005).

Niu, H., Wang, S., Ji, A. H. & Chen, G. Allelopathic effects of extracts of vicia villosa on the germination of four forage seeds. Acta Pratacul. Sin. 29, 161–168. https://doi.org/10.11686/cyxb2020003 (2020).

Li, J. X. et al. Allelopathic effect of artemisia argy ion the germination and growth of various weeds. Sci. Rep. 11, 4303. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-83752-6 (2021).

Jia, H., Li, B., Wu, Y., Ma, Y. & Yan, Z. The construction of synthetic communities improved the yield and quality of salvia miltiorrhiza bge. J. Appl. Res. Med. Aroma. 34, 100462. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jarmap.2023.100462 (2023).

Hu, H. et al. Allelo-pathic effects of aqueous extract from conyza canadensis on seed germination and seedling growth of two herbaceous flower species. Acta Botan. Boreali-Occiden. Sin. 43, 1528–1536. https://doi.org/10.7606/j.issn.1000-4025.2022.07.1189 (2023).

Li, W., Wei, G., Liu, X., Wei, L. & Yue, J. Allelopathic effects of fresh leaf extract of taxus wallichian var. mairei on seed germination and seedling growth of three medicinal plants. Shandong Agric. Sci. 55, 88–95. https://doi.org/10.14083/j.issn.1001-4942.2023.08.012 (2023).

Wang, C. et al. Effects of autotoxicity and allelopathy on seed germination and seedling growth in medicago truncatula. Front. Plant Sci. 13, 908426. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2022.908426 (2022).

Đorđević, T. et al. Phytotoxicity and allelopathic potential of juglans regia l. leaf extract. Front. Plant Sci. 13, 986740–986754. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2022.986740 (2022).

Liu, Z. et al. Phosphate-solubilizing microorganisms regulate the release and transformation of phosphorus in biochar-based slow-release fertilizer. Sci. Total Environ. 869, 161622. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.161622 (2023).

Patil, J. R. et al. Flavonoids in plant-environment interactions and stress responses. Discov. Plants 1, 68. https://doi.org/10.1007/s44372-024-00063-6 (2024).

Singleton, V. L., Orthofer, R., Lamuela-Raventós, R. M. Analysis of total phenols and other oxidation substrates and antioxidants by means of folin-ciocalteu reagent, methods in enzymology. Academic Press 299, 152–178 (1999). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0076-6879(99)99017-1

Wang, Y. et al. Functions, accumulation, and biosynthesis of important secondary metabolites in the fig tree (ficus carica). Front. Plant Sci. 15, 1397874. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2024.1397874 (2024).

Saffari, P., Majd, A., Jonoubi, P. & Najafi, F. Effect of treatments on seed dormancy breaking, seedling growth, and seedling antioxidant potential of agrimonia eupatoria l. J. Appl. Res. Med. Aromat. Plants. 20, 100282. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jarmap.2020.100282 (2021).

Stangarlin, J. R. & Pascholati, S. F. Allelopathic effects of amomum villosum lour. volatiles from different organs on selected plant species and soil microbiota. Summa Phytopathol. 26, 34–42 (2000).

Hu, Y. et al. Nitrate nutrition enhances nickel accumulation and toxicity in arabidopsisplants. Plant Soil. 371, 105–115. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-013-1682-4 (2013).

Zhang, C. P. et al. Role of 5-aminolevulinic acid in the salinity stress response of the seeds and seedlings of the medicinal plant cassia obtusifolia l. Bot. Stud. 54, 18–31. https://doi.org/10.1186/1999-3110-54-18 (2013).

Morales, M. & Munné-Bosch, S. Malondialdehyde assays in higher plants. Methods Mol. Biol. 2798, 79–100. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-0716-3826-26 (2024).

Funding

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82460364), Guangxi Science and Technology Plan for the Cultivation of Young Scientific and Technological Innovation Talents Project (No. GuiKeAD23026310), Guangxi Universities Young and Middle-aged Teachers’ Basic Research Capacity Enhancement Project (No. 2023KY0982), Guangxi Key Laboratory of Plant Functional Substances and Sustainable Resource Utilization Project (No. FPRU2020-4), and Guilin Normal College Guibei Characteristic Medicinal Resource Research Center Scientific Research Project (No. YJZX202302).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, C.C. and N.J.; Methodology, H.T.; Software, D.J; Validation, Y.T.; Formal analysis, C.C.; Investigation, C.C.; Resources, L.Z.; Data curation, C.C.; Writing—original draft preparation, C.C.; Writing—review and editing, C.C.; Visualization, D.J.; Supervision, J.N.; Project administration, C.C.; Funding acquisition, C.C. and D.J.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cao, C., Tian, H., Jiang, D. et al. Investigation of the allelopathic effect of two medicinal plant in agroforestry system. Sci Rep 15, 12258 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96070-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96070-y

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Elucidation of allelopathic potentialities of an invasive plant S. nodiflora towards an aggressive weed mimosa and documentation of the contributing allelochemicals

Journal of the Saudi Society of Agricultural Sciences (2025)