Abstract

Medial malleolus fracture is traditionally performed via an open approach. However, significant drawbacks such as exfoliated soft tissue injury, infection, prolonged recovery periods have been reported. Recently, arthroscopy-assisted reduction percutaneous internal fixation (ARPF) demonstrates advantages in minimizing soft tissue damage, improving joint visualization, and enhancing postoperative recovery, however, robust comparative evidence remains sparse on the efficacy of ARPF versus open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) in treating medial malleolus fractures. The current study provides preliminary evidence suggesting the potential utility of trauma response indexes and bone metabolism markers in clinical outcomes evaluation associated with these two surgical techniques. A retrospective study was conducted on 60 patients with medial malleolus fractures from January 2021 to November 2023, The patients were divided into the ARPF (arthroscopy-assisted reduction and percutaneous internal fixation) group (n = 28) and the ORIF (open reduction and internal fixation) group (n = 32). The differences in preoperative general data, intraoperative bleeding volume, operation time, hospital stay, bone union time, and preoperative, postoperative 1 day, postoperative 3 days inflammatory response indicators [C-reactive protein (CRP), interleukin-6 (IL-6), cortisol (Cor), norepinephrine (NE)] and preoperative, postoperative 2 weeks, 4 weeks bone metabolism markers [bone carboxyglutamicacid protein (BGP), bone alkaline phosphatase (BALP), β-collagen degradation products (β-CTX)] levels, and postoperative 6 months, 1 year Olerud–Molander Ankle Score (OMAS) were compared. No significant differences were observed in age, gender, injury side, or cause of injury between the two groups (P > 0.05). Compared to the ORIF group, the ARPF group exhibited reduced intraoperative blood loss, shorter hospital stays, and accelerated bone healing time. However, the duration of surgery was significantly longer (p < 0.05). Postoperative CRP levels on days 1 and 3 were lower in the ARPF group compared to the ORIF group. Similarly, IL-6 levels on days 1 and 3 were also lower in the ARPF group. Cor levels on days 1 and 3, as well as NE levels on days 1 and 3, were both lower in the ARPF group. At weeks 2 and 4 postoperatively, BGP and BALP levels were both higher, butβ-CTX levels were lower in the ARPF group. Additionally, the OMAS scores at 6 months and 1 year postoperatively were higher in the ARPF group. Arthroscopy-assisted reduction and percutaneous internal fixation for isolated medial malleolus fracture can minimize intraoperative bleeding, reduce trauma, expedite fracture healing, enhance ankle functional recovery, making it a valuable technique for clinical application.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Medial malleolus is a common clinical disease in ankle fractures. Traditional surgical management of these fractures typically involves open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF). While ORIF demonstrates satisfactory outcomes, it is associated with significant drawbacks, including extensive trauma, prolonged recovery periods, and suboptimal postoperative fracture healing1. Moreover, this technique lacks the precision required for thorough intra-articular lesion assessment and treatment, potentially leading to chronic pain, stiffness, and ankle joint instability following surgery2,3,4,5. Consequently, numerous researchers have highlighted the importance of arthroscopic evaluation5,6,7,8.

ARPF exemplifies a transformative advancement in orthopedic surgery, integrating arthroscopic visualization with minimally invasive percutaneous fixation. This technique markedly reduces soft tissue trauma, preserves periosteal vascular integrity, and facilitates direct intraoperative evaluation of articular components such as cartilage and ligaments, ensuring anatomical precision during fracture reduction5,6,7. Emerging evidence indicates that ARPF enhances the accuracy of fracture alignment, mitigates postoperative inflammatory responses (e.g., reduced CRP and IL-6 levels), and expedites functional recovery compared to conventional methods8,9,10. Nevertheless, robust comparative analyses between ARPF and ORIF remain sparse, particularly in quantifying objective biomarkers of systemic trauma (e.g., CRP, IL-6) and localized bone metabolism dynamics (e.g., BGP, β-CTX), which are critical for elucidating the mechanistic superiority of ARPF.

Current research primarily focuses on clinical outcomes such as fracture union time and functional scores, overlooking the biochemical and physiological mechanisms governing recovery processes. Trauma response markers (e.g., CRP, IL-6) and bone metabolism indicators (e.g., BGP, β-CTX) provide critical insights into the systemic and local impacts of surgical techniques11,12,13. This study aims to address these gaps by comprehensively comparing ORIF and ARPF in terms of intraoperative parameters, trauma response biomarkers, bone metabolism dynamics, and functional recovery. We hypothesize that ARPF will exhibit distinct advantages, including reduced inflammatory stress, enhanced osteogenic activity, and improved ankle function, thereby validating its role as a minimally invasive alternative to conventional ORIF. The findings may guide clinical decision-making and refine surgical protocols for medial malleolus fractures.

Methods

Study design

All isolated medial malleolus fracture patients who underwent either arthroscopy-assisted reduction percutaneous internal fixation or open reduction internal fixation between January 2021 and October 2023 were reviewed for eligibility. The inclusion criteria were: (i) All fractures were classified according to the AO/OTA classification for medial malleolar fractures which was limited to AO/OTA type 44A1 fractures (isolated, non-comminuted, vertical fractures with displacement > 2 mm); (ii) There is a fixed contact information to facilitate the visitors; (iii) Be able to conduct regular outpatient review and cooperate with visitors. The exclusion criteria were: (i) comminuted and open fracture of medial malleolus, maisonneuve fractures; (ii) Patients with an external posterior ankle fracture who cannot be operated under ankle arthroscopy; (iii) lower extremity arteriovenous thromboembolism or peripheral neuropathy; (iv) Patients with hypertension and diabetes, accompanied by serious heart, brain, lung, liver, kidney and other internal disease; (v) Those who have a long-term history of taking hormone drugs, and mental patients who do not cooperate with treatment; (vi) Follow-up time < 12 months. A total of 60 patients were enrolled in this study and were divided into two groups according to the surgical approach: In the ARPF group, there were 28 patients, including 20 male and 8 female patients, their mean age was 35.93 years (range: 20–56), 15 patients were on the left side and 13 on the right side; 5 patients were due to fall from height, 9 patients were due to traffic accident, 14 patients were due to sprain. In the ORIF group, there were 32 patients: 22 male and 10 female patients, their mean age was 36.38 years (range: 21–60),14 patients were on the left side and 18 patients on the right side, 10 patients were due to fall from height, 11 patients were due to traffic accident, 11 patients were due to sprain. Surgical operations were performed by two different experienced and the same rank of orthopaedists who was skilled in operating arthroscopic techniques. All patients were well informed by the orthopaedist about the specific surgical procedures, risks and benefits of the two operative techniques and ultimately chose one technique from the two and signed an informed consent document. All patients were subject to 12 months follow-up. All patients were classified into a group with ARPF and a group with ORIF. We collected patients’ data and baseline demographic and clinical characteristics was shown in Table 1. This study was reviewed and approved by Medical Ethics Committee of Shenzhen Longhua District Central Hospital (2019-080-01).

Operative technique

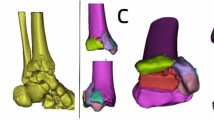

In the ARPF Group: All surgeries were performed under combined spinal-epidura anesthesia in the supine position. The surgical area was sterilised, a pneumatic tourniquet was applied. During the operation, A 2.7 mm, 30°arthroscope (Smith & Nephew, Andover, MA) was inserted into the ankle through a standard anteromedial portal, afterwards the standard anterolateral portal is performed in the same way. The cannula was used to protect tissue and guide the arthroscope into the joint cavity, if the joint space is narrow, an assistant assisted in traction of the ankle joint to increase the joint space. A systematic 21-point arthroscopic examination was performed to assess the articular anatomical structure, intraoperative treatment was performed according to the degree of ligament fiber tear and the depth of cartilage injury(two patients were found to have talar cartilage injury during the operation, The depth of the articular cartilage lesions was graded according to ICRS (International Cartilage Repair Society) arthroscopic grading system, two patients exhibited Grade II talar cartilage injuries, which were managed with microfracture. Partial tear (grade II per Park criteria) of the medial deltoid ligament was found in three patients and were treated with electrocoagulation and tightening. None of the patients had syndesmotic ligament injuries). Before reduction, hemarthrosis and debris were meticulously debrided by a high-speed shaver to expose fracture line (Fig. 1). At the distal end of the medial malleolus, a towel clamp was used to hold the fracture fragment, and with the help of the towel clamp, the fracture fragment was pushed proximally to go near the proximal tibia. Under the monitoring of the arthroscope, a hook needle was used by leveraging or pushing to achieve anatomic reduction. After observing under the arthroscope that the joint surface at the fracture site was smooth, towel clamps were used to temporarily fix both ends of the fracture, at the same time, a K-wire was drilled into the fracture site for temporary fixation. Then, two guide wires were drilled on both sides of the K-wire through the fracture sites, two 3.5 mm cannulated screws were driven over the guidewires (Fig. 2), the length and direction of each screw was measured by using preoperative radiographs and computed tomography scans (Fig. 3). Under the arthroscope, the smoothness of the medial joint was observed and evaluated, and it was checked whether the internal fixators penetrated the joint surface (Fig. 4). Finally, if the length and position of the screw was not certain intraoperatively, fluoroscopy was performed to confirm them.

In the ORIF Group: In supine position, combined lumbar and epidural anesthesia was used. Conventional surgical area was disinfected, towel was laid, a thigh tourniquet was applied. A standard curvilinear incision was made in order to better reveal the internal ankle surface and fracture gap. After The hematoma and soft tissue in the fracture gap were cleared, a Kirschner needle was drilled into the vertical fracture end for temporary fixation, and two guidewires were drilled into both sides of the Kirschner needle for temporary fixation through the fracture end. Two 3.5 mm cannulated screws were driven over the guidewires, C-arm fluoroscopy to confirm screw position and satisfactory reduction, remove the temporarily fixed Kirschner needle and guidewires, rinse and stitch the incision skin.

Postoperative care and rehabilitation

For both groups, postoperative management and rehabilitation were conducted in the same way. On the first day after surgery, quadriceps isometrical contraction training and passive range of motion (ROM) exercises of ankle joint were performed to reduce lower limb edema and prevent deep vein thrombosis, the duration might extend up to 2 weeks after surgery. Generally, the wound dressing was changed every 2–3 days. Partial weight-bearing was allowed at three weeks, and full weight-bearing was begun at eight weeks. Sports activity was allowed after a minimum of 3 months from surgery. Follow-up at 2 weeks, 1 month, 3 months, 6 months, 9 months and 12 months after surgery.

Changes in osteoarthritis were assessed using the Kellgren–Lawrence grading system, and osteochondral lesions were recorded by MRI (follow-up for 6 months) in conjunction with the International Society for Cartilage Repair (ICRS) grading criteria.

Clinical outcomes

The primary outcome measure was the Olerud–Molander Ankle Score (OMAS), a validated numeric scale ranging from 0 to 100 points used for subjective assessment following an ankle fracture23. This score was evaluated at 6 months and 1 year after surgery. The secondary outcomes included trauma response indexes, bone metabolism markers, operative indications and postoperative complications.

Trauma response indexes and bone metabolism markers: ① 4 mL of fasting venous blood was collected from patients before surgery, 1 day and 3 days after surgery, centrifuge for 10 min (rotation speed 3000r/min, centrifuge radius 8 cm), serum was collected, and frozen in the refrigerator at − 80℃ for examination. Serum C-reactive protein (CRP) levels were determined by immunoturbidimetry, serum interleukin-6 (IL-6) levels were determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, and IL-6 levels were determined by automatic biochemical analyzer (Mindray, BS-280), serum cortisol (Cor) and serum norepinephrine (NE) levels were measured with kits purchased from Shenzhen Mindray Biomedical Electronics Co. LTD. ② 4 mL of fasting venous blood samples were collected from patients before surgery, 2 weeks and 4 weeks after surgery. Serum was centrifuged and frozen at low temperature for detection (same method as above). Serum was determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay Serum bone carboxyglutamicacid protein (BGP), serum bone alkaline phosp-hatase (BALP),and serumβ-collagen degradation products (β-CTX) levels. The kits were purchased from Nanjing Jiangcheng Bioengineering Institute. The operation is strictly in accordance with the kit instructions.

Operative indicators: including intraoperative blood loss, operation time, fracture healing time. X-ray examination was performed regularly after surgery. If the examination shows that the fracture line has disappeared and the callus has formed extensively, the fracture was considered to be healed.

Postoperative complications: wound infection, joint stiffness, loosening of internal fixation.

Sample size estimation

The sample size was mainly based on continuous cases that met the inclusion criteria during the study period (a total of 66 cases), and excluded cases that did not meet the follow-up requirements (6 cases), and finally included 60 patients (28 cases in the ARPF group and 32 cases in the ORIF group). Although the study did not perform prior statistical Power analysis, we performed a power analysis for the primary outcome measure (OMAS) using G*Power 3.1 software after the fact. The effect size was set as 0.8 (Cohen’s d), α = 0.05, and test efficacy (1 − β) = 0.8. The calculation results showed that the required sample size was 26 cases/group, while the actual sample size (28 cases in ARPF group and 32 cases in ORIF group) met the requirements, indicating that the current sample size had sufficient statistical power.

During the study period, a total of 66 consecutive patients met the inclusion criteria. Among these, 1 patient from the ARPF group was excluded due to severe cerebral pathology, and 5 patients were lost to follow-up (2 from the ARPF group and 3 from the ORIF group). Consequently, the final sample comprised 60 patients: 28 in the ARPF group and 32 in the ORIF group.

Statistical analysis

This analysis follows the ITT principle. For the continuous quantitative data, if they were consistent with or approximately normal distribution, the mean ± standard deviation was used to describe them, and the comparison between the two groups was performed by t test. If the distribution did not conform to normal, the median [P25, P75] was used for statistical description, and rank sum test was used for inter-group comparison. For counting data, the number of cases (%) was used to describe, and the comparison between groups was performed by Chi-square test or Fisher exact probability method. The number of cases (%) was used for statistical description of rank data, and rank sum test was used for inter-group comparison. For continuous variable outcomes, linear regression was used to estimate inter-group differences and 95% confidence intervals, correcting for age, sex, injury side, and cause of injury in the model. The KM survival accumulation curve and log-rank test were drawn by using R language survminer package to compare the difference of healing rate under different groups. For repeated measurement data, this study used R language geepack package to perform generalized estimation equation model to estimate the difference between groups. The correlation structure was set as “exchangeable”, time, group and time*group were included in the model, and age, gender, injury side, cause of injury and corresponding preoperative level were corrected in the model. At the same time, the estimated mean values at different time points under different groups are visualized by line plots. Continuous variables were analyzed using independent t-tests if normally distributed (Shapiro–Wilk P > 0.05) or Mann–Whitney U tests otherwise. Categorical variables were compared via χ2 or Fisher’s exact tests as appropriate. Shapiro–Wilk tests confirmed normality for all continuous variables.

All statistical analyses and associated charts were conducted using the R programming language (version 4.4.1), Statistical significance was set at a two-tailed p < 0.05. Results are presented as mean ± SD or median [IQR], with 95% confidence intervals (CI) for intergroup differences..

Results

Patient general characteristics, including sex, age, injury side, cause of injury, are summarized in Table 1. The two groups did not differ in sex, age, injury side, cause of injury, and time interval to injury. There are trauma response indexes, bone metabolic markers and AOFAS at baseline in the Table1. Baseline fracture characteristics (AO/OTA type 44A1) were consistent across both groups, eliminating confounding from fracture complexity.

Comparison of surgical indicators

In terms of surgical indicators, the ARPF group had less blood loss than the ORIF group, and, hospital stay and bone healing time (mean difference: − 3.33 weeks; 95% CI − 4.12 to − 2.54; P < 0.001) are shorter than the ORIF group, but the operation time was longer the ORIF group, with significant statistical differences (p < 0.05) (Table 2).

Comparison of trauma response indexs

On the first postoperative day, the CRP level in the ORIF group increased by 21.50 (95% CI: 20.99–22.00, p < 0.001) from the baseline, whereas in the ARPF group, it increased by 13.18 (95% CI 12.80–13.57, p < 0.001). The intergroup difference was -8.31 (95% CI − 8.95 to − 7.68). On the third postoperative day, the CRP level in the ORIF group increased by 15.52 (95% CI 15.04–16.00, p < 0.001) from the baseline, while in the ARPF group, it increased by 7.45 (95% CI 7.04–7.86, p < 0.001). The intergroup difference was − 8.07 (95% CI − 8.71 to − 7.44). On the first postoperative day, the IL-6 level in the ORIF group increased by 9.31 (95% CI 8.57–10.05, p < 0.001) from the baseline, whereas in the ARPF group, it increased by 4.30 (95% CI 3.68–4.93, p < 0.001). The intergroup difference was − 3.00 (95% CI − 4.12 to − 1.88). On the third postoperative day, the IL-6 level in the ORIF group increased by 6.60 (95% CI 6.05–7.16, p < 0.001) from the baseline, while in the ARPF group, it increased by 4.30 (95% CI 3.68–4.93, p < 0.001). The intergroup difference was -2.30 (95% CI − 3.14 to − 1.47). On the first postoperative day, the Cor level in the ORIF group increased by 167.82 (95% CI: 165.04–170.60, p < 0.001) from the baseline, whereas in the ARPF group, it increased by 62.32 (95% CI 61.19–63.45, p < 0.001). The intergroup difference was − 105.50 (95% CI − 108.50 to − 102.50). On the third postoperative day, the Cor level in the ORIF group increased by 72.76 (95% CI 71.58–73.95, p < 0.001) from the baseline, while in the ARPF group, it increased by 30.35(95% CI 29.43–31.26, p < 0.001). The intergroup difference was − 42.42 (95% CI − 43.92 to − 40.92).On the first postoperative day, the NE level in the ORIF group increased by 1.06 (95% CI 1.02–1.10, p < 0.001) from the baseline, whereas in the ARPF group, it increased by 0.54 (95% CI 0.50–0.59, p < 0.001). The intergroup difference was − 0.52 (95% CI − 0.58 to − 0.45). On the third postoperative day, the NE level in the ORIF group increased by 0.54 (95% CI 0.53–0.56, p < 0.001) from the baseline, while in the ARPF group, it increased by 0.22 (95% CI 0.21–0.24, p < 0.001). The intergroup difference was − 0.32 (95% CI − 0.34 to − 0.30).Detailed trauma response indexes for each group are presented in Table 3 and Fig. 5.

Comparison of bone metabolism markers

At 2 weeks postoperatively, the BALP level in the ORIF group increased by 18.59 from the baseline (95% CI 18.13–19.05, p < 0.001), while in the ARPF group, it increased by 42.58 (95% CI 39.84–45.32, p < 0.001). The intergroup difference was 23.99 (95% CI 21.21–26.77).At 4 weeks postoperatively, the BALP level in the ORIF group increased by 30.37 from the baseline (95% CI 29.53–31.21, p < 0.001), and in the ARPF group, it increased by 63.62 (95% CI 60.58–66.65, p < 0.001). The intergroup difference was 33.25 (95% CI 30.10–36.39).Postoperatively, at 2 weeks, the BGP level in the ORIF group increased by 1.83 from the baseline (95% CI 1.65–2.00, p < 0.001), whereas in the ARPF group, it increased by 2.59 (95% CI 2.53–2.65, p < 0.001). The intergroup difference was 0.76 (95% CI 0.57–0.95). At 4 weeks postoperatively, the BGP level in the ORIF group increased by 2.60 (95% CI 2.42–2.78, p < 0.001), and in the ARPF group, it increased by 3.77 (95% CI 3.67–3.87, p < 0.001). The intergroup difference was 1.17 (95% CI 0.96–1.38). At 2 weeks postoperatively, the β-CTX level in the ORIF group decreased by 0.28 from the baseline (95% CI − 0.29 to − 0.27, p < 0.001), while in the ARPF group, it decreased by 0.42 (95% CI − 0.43 to − 0.41, p < 0.001). The intergroup difference was − 0.14 (95% CI − 0.15 to − 0.13). At 4 weeks postoperatively, the β-CTX level in the ORIF group decreased by 0.46 from the baseline (95% CI − 0.48 to − 0.44, p < 0.001), and in the ARPF group, it decreased by 0.50 (95% CI − 0.51 to − 0.48, p < 0.001). The intergroup difference was − 0.04 (95% CI − 0.06 to − 0.01). Detailed bone metabolism markers for each group are presented in Table 3 and Fig. 6.

3.4 Comparison of OMAS

The Comparison of OMAS are shown in Table 4. At all follow-up intervals, the mean OMAS was higher in the ARPF group than in the ORIF group. The differences were statistically significant at 6 months (83.9 ± 4.2 for ARPF vs 75.4 ± 4.8 for ORIF, p < 0.001) and 1 year (93.6 ± 5.1 vs 83.9 ± 5.6, P < 0.001).

Comparison of complications

The incidence of postoperative complications is summarized in Table 5. Both groups exhibited low rates of complications, with no statistically significant differences observed between the ARPF and ORIF groups (P > 0.05 for all comparisons).Wound infection: One case (3.12%) occurred in the ORIF group, while no infections were reported in the ARPF group (P = 1.000). Joint stiffness: Two patients (6.25%) in the ORIF group and one patient (3.57%) in the ARPF group developed joint stiffness (P = 1.000). Loosening of internal fixation: One case (3.12%) was observed in the ORIF group, whereas none occurred in the ARPF group (P = 1.000).

During follow-up, neither group developed progressive osteoarthritis (Kellgren–Lawrence grade ≥ 2). In the ARPF group, 2 patients were found to have grade II talar cartilage injury during the operation (after microfracture treatment), and postoperative MRI showed good cartilage repair and no progression of the lesion.

Discussion

Fractures of the medial malleolus are a frequent occurrence among ankle fractures. Currently, surgical intervention is recommended for displaced medial malleolus fractures. Lloyd et al.11 demonstrated through biomechanical studies that a 1 mm displacement of the talus relative to the tibia results in a reduction of at least 42% in the contact area of the tibio-talar joint, leading to increased local stress on the articular surface, which accelerates the development of cartilage ischemic necrosis. Consequently, this can progress to traumatic ankle arthritis. Therefore, the prevailing clinical consensus is that surgical anatomical reduction and internal fixation should be employed when fracture displacement meets the criteria for surgical intervention, with anatomical reduction being essential for optimal ankle joint function. Open reduction and internal fixation provide full exposure of the medial ankle fracture line; however, this procedure necessitates incising the periosteum and dissecting surrounding tissues. If the medial articular surface requires visualization, the skin incision must be extended, followed by cutting the medial joint capsule, which can easily damage the great saphenous vein and saphenous nerve without meticulous dissection. Furthermore, the soft tissue surrounding the medial ankle is inherently limited. If the extent of skin and soft tissue dissection is extensive and the tissue is excessively stretched during surgery, the risk of skin and soft tissue ischemic necrosis and infection increases. Arthroscopy has increasingly been utilized in orthopedic conditions, and a growing number of researchers acknowledge the positive impact of ankle arthroscopy on the management of ankle disorders12,13.The application of ankle arthroscopy not only shortens the surgical incision but also minimizes tissue damage. In cases of ankle joint fractures involving the articular surface, surgeons can use an ankle arthroscope to thoroughly examine the anatomical structure of the ankle joint, thereby obtaining a clearer view of the cartilage surface and surrounding ligament injuries, facilitating more precise intraoperative diagnosis. Furthermore, the arthroscope offers a more intuitive understanding of the fracture condition, enhancing the accuracy of articular surface fracture reduction14,15. Compared to traditional open incisions, patients undergoing arthroscopic surgery require only two 2–3 mm skin incisions, thus avoiding the great saphenous vein and its accompanying saphenous nerve. Postoperatively, there are no visible scars, and minimal adhesion of surrounding soft tissues is observed. In this study, all patients who underwent arthroscopic surgery achieved grade A wound healing, experienced mild postoperative swelling of the affected limb, and did not report numbness around the ankle.

Surgical trauma and stress indices were quantified to compare tissue injury between groups. Surgical trauma triggers an inflammatory stress response in the body, leading to changes in internal environmental indicators. Assessing the expression levels of these indicators provides an objective basis for evaluating surgical trauma16. In this study, the impact of two surgical procedures on inflammatory stress markers was assessed. The results indicated that serum C-reactive protein (CRP), interleukin-6 (IL-6), cortisol (Cor), and norepinephrine (NE) levels in the arthroscopic group were significantly lower compared to those in the open incision group at 1 and 3 days post-surgery. CRP is a critical inflammatory marker reflecting systemic inflammation and is closely linked to postoperative tissue damage. IL-6, a 184-amino acid protein with a molecular weight of 21 kDa, is secreted by monocytes, fibroblasts, and endothelial cells. During acute inflammatory responses, the levels of inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and IL-10 increase rapidly17,18,19. Studies have shown that serum IL-6 levels rise markedly with the severity of fracture trauma20. This is due to IL-6 being a cytokine produced by macrophages, neutrophils, and lymphocytes in response to injury, with high expression during callus formation. The more severe the tissue trauma, the higher the IL-6 concentration. Cortisol and norepinephrine serve as indicators of the stress response, with their levels positively correlating with the extent of the trauma response. These findings suggest that arthroscopic closed reduction and percutaneous internal fixation can effectively reduce the body’s trauma response, thus confirming the minimally invasive nature of these techniques at the laboratory level.

In this study, we aimed to gain a deeper understanding of the alterations in bone metabolism indices among fracture patients during the healing process. BALP primarily indicates osteoblast activity, and an elevation in its expression signifies enhanced osteogenic activity. BGP reflects both the osteogenic capacity of osteoblasts and excessive bone mineralization and proliferation, whereas β-CTX is indicative of osteoclast activity and the extent of bone resorption21. Our findings revealed that, at the second postoperative week, the differences in BGP and BALP levels between the ORIF group and the ARPF group were 0.76 (95% CI 0.57 to 0.95) and 23.99 (95% CI 21.21 to 26.77), respectively, indicating that ARPF led to a greater increase in BGP and BALP compared to ORIF. At the fourth postoperative week, the differences in BGP and BALP levels between the ORIF and ARPF groups were 1.17 (95% CI: 0.96 to 1.38) and 33.25 (95% CI: 30.10 to 36.39), respectively, further suggesting that ARPF resulted in a more significant increase in BGP compared to ORIF. The difference in β-CTX levels between the ORIF group and the ARPF group was − 0.14 (95% CI: − 0.15 to − 0.13), indicating that ARPF resulted in a greater increase in β-CTX compared to the ORIF group. At the 4th week post-surgery, the difference in β-CTX levels between the ORIF group and the ARPF group was − 0.04 (95% CI: − 0.06 to − 0.01), suggesting that ARPF reduced the increase in β-CTX relative to the ORIF group. This can be attributed to the fact that closed reduction and percutaneous internal fixation under arthroscopy cause minimal damage to the periosteal blood supply at the fracture site and have a limited impact on the local blood circulation, thereby promoting fracture healing and shortening the healing time. This finding is in line with Kumar et al.21. The proposed predictive role of bone metabolic markers in fracture healing is echoed. The difference of β-CTX further supports the regulatory advantage of ARPF on bone resorption process. The combined analysis of these biomarkers not only validates the minimally invasive benefits of ARPF, but also provides a quantifiable biological endpoint for future research.

The OMAS scale serves as an objective instrument for assessing ankle joint function, demonstrating high reliability and validity. At 6 months and 1 year post-operation, the OMAS scores were significantly higher in the arthroscopic group, indicating that percutaneous internal fixation performed in a closed arthroscopic position can enhance ankle joint function. The underlying reasons for this improvement include the following: conventional ORIF surgery involves larger incisions, prolonged postoperative wound healing times, significant local pain, extended intraoperative exposure of the fracture site and surrounding soft tissues, which can lead to a higher incidence of local infections, hinder early patient mobilization, reduce the range of motion, and impede the functional recovery of the ankle joint10. Arthroscopic closed reduction and percutaneous internal fixation allows for the arthroscope to access the affected area through a minimally invasive incision, enabling a comprehensive and clear observation of the fracture site. This technique ensures a clearer surgical field, thereby preventing the exposure and secondary injury to the fracture site and adjacent soft tissues that might result from a larger incision. It also helps in reducing intraoperative blood loss, minimizing the impact on the local blood circulation, and accelerating patient recovery post-surgery. Additionally, this method reduces the risk of complications such as delayed fracture healing, joint stiffness, and local infections. The rapid postoperative recovery and reduced pain facilitate early rehabilitation training and enhance the functional recovery of the ankle joint.

In this study, arthroscopic examination revealed cartilage injury in two patients, and no signs of osteoarthritis were observed during the one-year follow-up period. These findings align with those reported by Ono et al.5 regarding cartilage injuries. Currently, there is a divergence of opinion concerning the prevalence of cartilage injuries associated with ankle fractures. Hintman et al.7 documented that 79.2% of patients with acute bimalleolar fractures exhibited cartilage damage. Leotaridis et al.2 conducted arthroscopic evaluations on 83 patients with ankle fractures prior to open reduction and internal fixation, identifying cartilage damage in 73% of cases. We hypothesize that the discrepancies in the reported incidence of cartilage injury across these studies could be attributed to variations in the definition of cartilage injury or differences in the types of ankle fractures examined. Regarding the progression to osteoarthritis in patients with cartilage injury, Stufkens et al.22 highlighted a direct correlation between the clinical manifestation of arthritic symptoms and the depth of cartilage injury (exceeding 50% of cartilage thickness). Given the limited follow-up duration of our study and the focus on isolated medial malleolar fractures, the incidence of osteoarthritis resulting from ankle fractures complicated by cartilage injury may vary.

Despite the limited sample size, the generalized estimating equation (GEE) model employed in this study accounted for repeated measurements and adjusted for covariates (age, sex, injury side, cause of injury). The significant intergroup differences in trauma response markers, bone metabolism dynamics at early follow-up timepoints (1 day, 3 days, 2 weeks) underscore the robustness of these preliminary findings. Further validation through multicenter trials with larger cohorts is warranted to confirm these observations.

The limitations of this study include the limited sample size and the relatively short follow-up period. Given that the clinical outcomes of intra-articular fractures are closely associated with intra-articular changes, a longer follow-up duration (> 12 months) may yield more accurate and comprehensive clinical results and evaluate the incidence of late complications (e.g., osteoarthritis). Additionally, another limitation is that the surgeons in the arthroscopic group and the open surgery group were of the same seniority level but different individuals. This variation in surgeons could potentially influence the study results due to differences in their experience, professional knowledge, and surgical skills. In addition, This study employed exploratory analyses for secondary outcomes (e.g., inflammatory markers), and the potential for type I error due to multiple comparisons should be acknowledged. Future confirmatory studies with predefined hierarchical testing procedures are warranted. Lastly, this study was a retrospective design without rigorous pre-calculation of sample size, and although post-efficacy analysis showed that the current sample size was sufficient to support the statistical validity of the primary outcome, future studies should further verify the robustness of the results through prospective design combined with prior efficacy analysis.

Conclusion

Arthroscopy-assisted reduction and percutaneous internal fixation for isolated medial malleolus fractures is a valuable technique for clinical application can, it can accurately reduce and percutaneous internal fixation, minimize intraoperative bleeding, reduce trauma, expedite fracture healing, enhance ankle functional recovery, reduce postoperative complications, compared with open reduction and internal fixation. Diagnostic and therapeutic advantages brought by the use of arthroscope in fixation of ankle fractures may present this technique as an important adjunct to estimate the long-term prognosis post fracture and to improve the clinical outcomes. Through multidimensional biomarker analysis, this study revealed the mechanism advantages of ARPF in reducing inflammatory stress, promoting bone metabolism and accelerating functional recovery. This finding provides a new theoretical basis for individualized treatment strategies for ankle fractures and highlights the potential value of biomarkers in the evaluation of orthopedic efficacy.

Data availability statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its supplementary materials.

References

Baumbach, S. F., Böcker, W. & Polzer, H. Arthroscopically assisted fracture treatment and open reduction of the posterior malleolus : New strategies for management of complex ankle fractures. Video article. Der Unfallchirurg 123(4), 330–338. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00113-020-00787-6 (2020).

Leontaritis, N., Hinojosa, L. & Panchbhavi, V. K. Arthroscopically detected intra-articular lesions associated with acute ankle fractures. J. Bone Joint Surg. 91(2), 333–339. https://doi.org/10.2106/JBJS.H.00584 (2009).

Thordarson, D. B., Bains, R. & Shepherd, L. E. The role of ankle arthroscopy on the surgical management of ankle fractures. Foot Ankle In 22(2), 123–125. https://doi.org/10.1177/107110070102200207 (2001).

Dawe, E. J., Jukes, C. P., Ganesan, K., Wee, A. & Gougoulias, N. Ankle arthroscopy to manage sequelae after ankle fractures. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 23(11), 3393–3397. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-014-3140-0 (2015).

Ono, A. et al. Arthroscopically assisted treatment of ankle fractures: Arthroscopic findings and surgical outcomes. Arthroscopy 20(6), 627–631. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arthro.2004.04.070 (2004).

Kralinger, F., Lutz, M., Wambacher, M., Smekal, V. & Golser, K. Arthroscopically assisted reconstruction and percutaneous screw fixation of a Pilon tibial fracture. Arthroscopy 19(5), E45. https://doi.org/10.1053/jars.2003.50165 (2003).

Hintermann, B., Regazzoni, P., Lampert, C., Stutz, G. & Gächter, A. Arthroscopic findings in acute fractures of the ankle. J Bone Joint Surg Br 82(3), 345–351. https://doi.org/10.1302/0301-620x.82b3.10064 (2000).

Panagopoulos, A. & van Niekerk, L. Arthroscopic assisted reduction and fixation of a juvenile Tillaux fracture. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 15(4), 415–417. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-006-0152-4 (2007).

Turhan, E. et al. Arthroscopy-assisted reduction versus open reduction in the fixation of medial malleolar fractures. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol 23(8), 953–959. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00590-012-1100-2 (2013).

Liu, C. et al. Arthroscopy-assisted reduction in the management of isolated medial malleolar fracture. Arthroscopy 36(6), 1714–1721. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arthro.2020.01.053 (2020).

Lloyd, J., Elsayed, S., Hariharan, K. & Tanaka, H. Revisiting the concept of talar shift in ankle fractures. Foot Ankle Int 27(10), 793–796. https://doi.org/10.1177/107110070602701006 (2006).

Atesok, K. et al. Arthroscopy-assisted fracture fixation. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 19(2), 320–329. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-010-1298-7 (2011).

Luo, H. et al. Minimally invasive treatment of tibial pilon fractures through arthroscopy and external fixator-assisted reduction. Springerplus 5(1), 1923. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40064-016-3601-7 (2016).

Braunstein, M., Baumbach, S. F., Regauer, M., Böcker, W. & Polzer, H. The value of arthroscopy in the treatment of complex ankle fractures-a protocol of a randomised controlled trial. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 17, 210. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-016-1063-2 (2016).

Fuchs, D. J., Ho, B. S., LaBelle, M. W. & Kelikian, A. S. Effect of arthroscopic evaluation of acute ankle fractures on PROMIS intermediate-term functional outcomes. Foot Ankle Int 37(1), 51–57. https://doi.org/10.1177/1071100715597657 (2016).

Fang, J., Dong, H. & Li, Z. Comparison of curative effects between minimally invasive percutaneous lag screw internal fixation and reconstruction plate for unstable pelvic fractures. J. Coll. Phys. Surg. Pak. 30(1), 28–32. https://doi.org/10.29271/jcpsp.2020.01.28 (2020).

Ma, L. et al. The acute liver injury in mice caused by nano-anatase TiO2. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 4(11), 1275–1285. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11671-009-9393-8 (2009).

Dudas, J., Mansuroglu, T., Batusic, D. & Ramadori, G. Thy-1 is expressed in myofibroblasts but not found in hepatic stellate cells following liver injury. Histochem. Cell Biol. 131(1), 115–127. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00418-008-0503-y (2009).

Midwood, K. S. & Orend, G. The role of tenascin-C in tissue injury and tumorigenesis. J. Cell Commun. Signal. 3(3–4), 287–310. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12079-009-0075-1 (2009).

Prystaz, K. et al. Distinct effects of IL-6 classic and trans-signaling in bone fracture healing. Am. J. Pathol. 188(2), 474–490. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajpath.2017.10.011 (2018).

Kumar, M., Shelke, D. & Shah, S. Prognostic potential of markers of bone turnover in delayed-healing tibial diaphyseal fractures. Eur. J. Trauma Emerg. Surg. 45(1), 31–38. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00068-017-0879-2 (2019).

Stufkens, S. A., Knupp, M., Horisberger, M., Lampert, C. & Hintermann, B. Cartil-age lesions and the development of osteoarthritis after internal fixation of ankle fractures: a prospective study. J. Bone Joint Surg. 92(2), 279–286. https://doi.org/10.2106/JBJS.H.01635 (2010).

Olerud, C. & Molander, H. A scoring scale for symptom evaluation after ankle fracture. Arch. Orthop. Trauma. Surg. 103(3), 190–194. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00435553 (1984).

Acknowledgements

We thank Kai Deng and Feiqiang Chen for proof reading this article. Without their helps, I can’t submit this manuscript smoothly.The study was sponsored by the Scientific Research Projects of Medical and Health Institutions of Longhua District, Shenzhen (2020159).

Funding

The study was sponsored by the Scientific Research Projects of Medical and Health Institutions of Longhua District, Shenzhen, (2020159).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Xihong Xie wrote the main manuscript text ,designed the study,finished the statistics and make all the tables. Danting Ji counted cases and collected datas. Feiqiang Chen supervised the writing of the paper and finished the figures production. Zejin Lin counted cases and collected datas. Kai Deng assisted in writing the manuscript. Jinqi Song assisted in finishing the statistics. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Statement in the methods

All methods were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xie, X., Ji, D., Chen, F. et al. Arthroscopic versus open fixation for medial malleolus fractures improves trauma response and bone healing. Sci Rep 15, 15050 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96078-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96078-4