Abstract

In metal cutting, the extreme tool temperature restricts the material removal rate. To address this, it is crucial to adopt techniques that reduce heat input and enhance heat dissipation from the cutting tool inserts. Rake surface texturing, particularly with micro-pillars, is gaining popularity in this context. Direct measurement of the cutting tool temperature is exceptionally challenging, so a numerical approach is adopted in this work to inverse estimate the tool tip temperature based on the temperature measured at a distant location from the rake face. Stage I of the work involved the development of a circular micro-pillar array on tungsten carbide inserts using the Reverse Micro Electrical Discharge Machining (RµEDM) technique. Based on the discharge pulses recorded during RµEDM, the 110V–100 nF voltage-capacitance combination proved feasible for this operation. In Stage II, turning operations were performed on Ti6Al4V alloys under dry, compressed air, and wet conditions. The tool temperature measured at the distant location revealed a substantial temperature drop for textured tools. This is attributed to the reduced contact area at the interface, as observed from the rake morphology of the tools, and to the enhanced heat dissipation from the higher surface area of the developed textures, as revealed by the computational fluid dynamics-based numerical study in Stage III of the work. An array of closely spaced, small-diameter, and higher-depth micro-pillars beyond the tool-chip contact area could enhance heat dissipation from the cutting tools.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Increasing the cutting speed and/or the feed rate of machining operations may significantly enhance the productivity of any manufacturing industry. However, this enhancement is restricted due to the shortened tool life caused by excessive stress and heat generation at higher cutting speeds and feeds. A significant fraction of the heat generated during the chip formation process in the primary shear zone is carried away by chips while the remaining heat is conducted into the workpiece, raising its temperature. However, due to the minimal tool-chip contact area for a brief period, this part of heat generation makes a negligible contribution to heating the cutting tools1. The heat generated at the secondary shear zone directly affects the tool life and significantly constrains the material removal rate. The contact between the moving chips and the rake surface of the tool is so nearly complete that sliding is almost impossible over a large portion of the total contact interface. To sustain a continuous chip flow under the condition of seizure, excessive shearing of the chip underside is witnessed, confined to a thin region adjacent to the interface. The heat generated from this additional plastic strain is conducted directly into the tool, raising its temperature1. Heat generation is further amplified in the case of heat-resistant titanium and nickel-based superalloys due to their superior mechanical and poor thermal properties2.

The constraints imposed by the cutting temperatures have stimulated tool material development, from cast steel in 1742 to Mushet’s tool steel in 1868, followed by High-Speed Steel (HSS) in 19063. HSS allows cutting speeds twice that of Mushet’s steel and four times that of cast steel. The development of superior metals led to the adoption of cemented carbides in the mid-1920s. The adoption of sintered cubic boron nitride and sintered polycrystalline diamond as tool materials was reported in 1969 and the early 1970s4. Apart from the development of the tool materials, considerable research has been carried out on the surface coating of the tools. Coated carbide tools were first reported in the 1970s4. Modern-day cutting tools have three or more layers of generally used materials like TiC, TiN, Al2O3, etc.4,5. Coatings facilitate the reduction of friction, which retards wear at the interface. Materials with low thermal conductivity are also used to create a thermal barrier at the interface5. Solid lubricants like MoS2 and CaF2 used in conjunction with coated tools have been reported to reduce friction considerably during machining6. The material removal rate has improved significantly with these superior cutting materials and coating techniques. However, the problem of high-temperature generation persists, especially for heat-resistant superalloys, which are still machined at a comparatively lower speed than steel7.

The go-to solution for enormous heat generation is applying cutting fluids. Cutting fluids helps heat dissipation from the cutting zone faster and lubricates the tool-chip contact area. However, the associated ecological hazards, economic costs, occupational diseases, and stringent government policies discourage the extensive use of cutting fluids5,8,9. Several other strategies are being explored to compensate for the cutting fluids. Researchers have explored externally assisted mechanisms like laser, vibration, or both. In laser-assisted machining, a laser heat source creates localized thermal softening in the workpiece material to ease its machining. This approach has helped reduce tool wear and improve the material removal rate due to the reduction in cutting forces10,11. Vibration-assisted machining periodically disrupts the intimate contact between the tool and the workpiece, interrupting the tool’s continuous heat supply. The high frequency and small amplitude vibrations help improve the tool life under dry machining12,13. Tool texturing is another approach that is gaining much interest in the machining domain. It involves the development of micro/nano features on the tool’s surfaces, intending to reduce interface contact area and improve tribological conditions in this region14,15,16,17,18. Micro-pillared textures can restrict the seizure zone by initiating faster curling of the flowing chips19. These micro-scaled features protruding from the tool’s rake face are expected to act as heat exchangers, rejecting heat from the tool body into the surroundings20,21. To investigate the effectiveness of these textures as heat exchangers, accurate temperature measurement and its distribution on the tool surface is necessary.

Estimating temperature and its distribution around the tool’s cutting edge is quite challenging due to the continuously moving chips in this region and the intimate contact at the interface22. Cutting temperature can be experimentally measured by direct conduction techniques using tool-work thermocouples or embedded thermocouples, indirect radiation technique using infrared thermography or pyrometer, and metallographic techniques. In a tool-work thermocouple, the tool-chip interface acts as a hot junction, while the tool or the workpiece acts as a cold junction. The measured temperature is the mean of the entire interface; hence, the locally generated high temperatures cannot be captured23,24. An embedded thermocouple is used to measure the temperature of a fixed point or multiple fixed points below the rake surface of the tool25,26. Several holes must be drilled into the inserts to station the thermocouples, which alters the tool strength and heat flow. Drilling holes into the hard tool inserts is also very challenging. The temperatures measured below the rake surface are used to estimate the temperature of the cutting zone using the inverse heat conduction method27. Accurate calibration, slow response, and noise are the major problems associated with the thermocouple techniques22. Due to its non-contact nature, radiation-based methods do not require pre-drilled holes, eliminating the impact on tool strength and heat flow. It also has a faster response compared to thermocouples. In a recent work, an infrared detector-based high-speed transient temperature measuring system was developed to measure the temperature rise of tool tip during high-speed machining of Ti6Al4V28. However, the significant challenges reported in radiation-based methods are chip obstruction and surface emissivity determination. The obscured view created by cutting fluid restricts this method only to dry machining. In the metallographic technique, temperature estimation is based on the microstructure and microhardness of the cutting tool, analyzed after machining. For an accurate estimate, the tool material should undergo observable microstructural and hardness changes with temperature, in the range of 600–1000 °C. Therefore, this method is restricted mainly to HSS; however, iron-bonded cemented carbides have been reported to experience such metallographic changes with temperature29. Based on the complexity of the machining process and the challenges associated with each measuring technique, no consensus is established between the results from different measuring techniques22. Several studies have reported using Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) to investigate the heat transfer, cutting fluid flow, and mechanical deformation of the cutting tools during machining30,31,32. The flow of high-pressure coolants via internal cooling channels on the cutting tool inserts was investigated using CFD simulations for turning Inconel 718. The study reveals that heat transfer from the tool was significantly enhanced33. Another work used CFD to explore the effect of internal cooling channel profiles on heat dissipation through the cutting tools. To replicate the heat generated during the turning operation, a uniform heat flux was applied at the tip of the tool32. However, this study did not consider the tool/chip contact area as the source of heat in the tool.

In this work, Reverse Micro Electrical discharge machining (RµEDM) in combination with Laser Beam Micro Machining (LBµM) is utilized to fabricate the micro-pillars that emulate pin-fins on uncoated tungsten carbide (WC) turning inserts. During the RµEDM, the discharge voltages are captured to analyze the effect of input voltage and capacitance on the texture fabrication. Turning experiments are conducted on a Ti6Al4V rod using textured and plain tools under dry, compressed air, and wet conditions. Cutting tool temperatures were measured at a distant location from the tooltip using embedded thermocouples, and the tool-chip contact area over the rake face was also measured. Using these two experimental data as input, inverse estimation of the tooltip temperature is attempted in this study using a CFD-based numerical approach. This approach helps gain insights into the micro-pillars’ enhancement of heat dissipation. Furthermore, to maximize the effectiveness of the textures, various sizes of the micro-pillars are examined.

Materials and methods

This section discusses the adopted approach for fabricating the micro-pillared structures on the rake face of turning inserts, followed by the turning experiment setup. The CFD modeling and boundary conditions are discussed at the end.

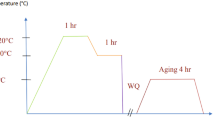

Texture fabrication

The micro-pillar texture profiles were fabricated using the RµEDM process. This Electrical Discharge Machining (EDM) variant has been explored in the literature for fabricating micro-pillars20,34. LBµM is employed to fabricate the tool plate consisting of the arrayed micro-holes, which is the negative replica of the micro-pillar profile. This tool plate aids in fabricating the micro-pillars on the WC inserts using RµEDM, refer to Fig. 1a,b. The LBµM and RµEDM process parameters are listed in Tables 1 and 2. The non-isoenergetic pulses in an RC-based µEDM process make it challenging to estimate the MRR and surface finish at different voltages and capacitances. Therefore, it is imperative to acquire live discharge data to gain insight into the material removal process35. During the fabrication of the micro-pillars, discharge voltage was captured and analyzed to study the effect of input voltage and capacitance on the texture fabrication process. Figure 1c illustrates the hybrid micromachining center (Mikrotools, DT110i) housing the LBµM and RµEDM setup. A plain tool and a micro-pillar fabricated texture tool are shown in Fig. 2. The average measured pitch between two successive micro-pillars is 98 µm, and the fabricated circular micro-pillars’ diameter is 302 µm.

Turning experiment

Turning experiments were conducted on a Ti6Al4V rod using the fabricated micro-pillar tool inserts and plain tool inserts. This study examined three machining conditions: dry, compressed air, and flood conditions. Each experiment was repeated for a minimum of two times. The process parameters and machining conditions used in this study are listed in Table 3. The experimental setup is shown in Fig. 3. K-type thermocouples were used to measure the cutting tool temperature at a distant location (point A) from the tooltip for all the machining conditions, as indicated in Fig. 4. The micro-EDM process was used to drill blind holes on the rear side of turning inserts to embed the thermocouple at point A. The tools used during the turning operation were observed under a scanning electron microscope to determine the tool-chip sticking contact area at the interface under all machining conditions. The measured temperature at point A and the measured sticking contact area are used for inverse estimation of the tool tip temperature using CFD-based numerical simulations later in the study.

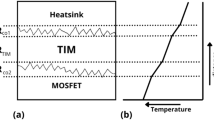

Simulation procedure and boundary conditions

ANSYS Fluent was used to perform the CFD simulations. The CAD model of the tools was prepared using SOLIDWORKS and imported into the ANSYS workbench. To avoid the high computational time, only the part of the insert involved in machining was modeled and analyzed. A control volume was defined on the tool’s rake face for fluid flow, see Fig. 5. Since the cutting fluid/air cannot penetrate the tool-chip contact area2, the control volume was defined from the end of the contact region. The entry and exit boundary conditions were pressure inlet and pressure outlet. A pressure inlet was chosen to replicate the pressurized fluid flow from an external source at the entry. The standard K-Ɛ model was used to model the turbulent flow of the fluid . The fluid and the solid interface have been defined as a coupled system for better heat transfer. A uniform heat flux was applied over the experimentally obtained tool/chip contact area, such that the simulated temperature matched the experimentally measured temperature at point A (see Fig. 4). This approach led to the determination of total heat entering the cutting tool and, hence, the tool tip temperature under the various machining conditions. A similar approach of using a uniform heat flux was adopted earlier32,36. The properties of the WC insert and the fluids used in the simulation are listed in Table 4. Different values of micro-pillar diameter, pitch, and depth are explored in this work to study the effect of micro-pillar dimensions on its heat dissipation capability, summarised in Table 5.

Governing equations

In the current problem statement, the input heat shall be conducted into the tool body through conduction. This heat shall then be dissipated by the fluid flowing over the rake face through convective heat transfer. The conduction heat energy equation is represented in Eq. (1). Here, ρt denoted the density of the tool insert, C is the heat capacity, and K is the thermal conductivity of the insert.

The heat conducted into the tool body is dissipated from the rake surface via convention to the fluid flowing over the surface. This governing equation is given by Eq. (2).

here \(\dot{Q}\) is the heat transferred per unit time, h is the heat transfer coefficient, A is the surface area of the insert over which the fluid flows, T is the surface temperature of the insert, and Tf is the fluid temperature. The surface area term in Eq. (2) highlights the advantage of increasing the surface area to accelerate the heat dissipation from the hot body. The development of micro-pillars on the rake face is intended to exploit this feature of the heat transfer process. In CFD, the mass, momentum, and energy conservation approach is used to simulate the problem. The continuity equation gives the mass conservation equation as Eq. (3).

where u, v, w are the fluid velocity in the x, y, and z directions. The Navier–stokes equation gives the momentum conservation equation as Eqs. (4a), (4b) and (4c). Its conservation equation includes the pressure, viscous, and body forces.

where ρ is the fluid density, µ is the fluid viscosity, and Fx, Fy, and Fz are the forces acting on the fluid in x, y, and z directions. Energy conservation is based on the first law of thermodynamics, according to which the net energy in a control volume is equal to the energy entering the control volume minus the heat going out. Equation (5) expresses the energy conservation equation. Here, Cp is the fluid’s specific heat, and λ is the thermal conductivity of the fluid.

Results and discussions

The results from all three stages of the present work are compiled here, and a detailed discussion is provided. Firstly, the discharge voltage recorded during the RµEDM experiments is analyzed to gain insight into the effect of input voltage and capacitance in the fabrication of arrayed micro-pillars. Secondly, the measured cutting tool temperature and tool-chip contact area from the turning experiments are analyzed for different machining conditions. Finally, the obtained experimental data from the turning experiments are used to perform CFD simulations to inversely estimate the cutting tool temperature and explore the heat dissipation capability of the micro-pillar textured inserts.

Stage I: fabrication of arrayed micro-pillar on turning inserts

Given that the voltage and capacitance are the prime input parameters controlling the RµEDM process’s output response, machining was performed at three different voltages, 90 V, 100 V, and 110 V, to decide on a suitable input voltage. The capacitance was kept constant at 100 nF during this trial. The discharge voltages recorded for these three input voltages are displayed in Fig. 6. An excessive short circuit is observed in 90 V and 100 V (Fig. 6a,b), indicating that these input voltages are unsuitable for machining an array of micro-pillars. On increasing the voltage to 110 V, continuous charging and discharging of the capacitor is observed, which results in constant spark generation and material removal (Fig. 6c,d). Accumulation of debris fills the narrow inter-electrode gap between the tool plate and the workpiece, causing the potential difference to drop to zero, resulting in a short circuit. The discharge gaps (inter-electrode gap) at four different input voltages ranging from 90 to 120 V were measured and compiled in Fig. 7. The excessive short-circuiting observed in 90 V and 100 V indicates that an average discharge gap of 2.3 µm and 4.5 µm is highly narrow for the dielectric to access the region and flush the debris. A discharge gap of 6.1 µm corresponding to the continuous spark generation at 110 V indicates that a gap above this shall overcome the problem of debris accumulation and short-circuiting. However, it does not imply that higher voltage is always beneficial. It has been observed that a higher voltage generates a wider discharge gap, but it also promotes overcut and inaccurate profile dimensions37. Therefore, an input voltage of 110 V is fixed for this study as a trade-off between short-circuiting and overcut.

To determine a suitable capacitance value for the fabrication of arrayed micro-pillars, four sets of capacitors (68 nF, 100 nF, 120 nF, and 150 nF) are explored at the previously determined input voltage of 110 V. The discharge voltages recorded during machining and the final machined surfaces are depicted in Figs. 8 and 9. The spark frequency can be observed as a differentiating parameter among these capacitor values from Fig. 8. Frequent sparking is witnessed at the lowest capacitance, while the least is observed at the highest. At low capacitance (68 nF), due to low input energy, the amount of material removed per spark is less, as evident from the fine craters on the machined surface (Fig. 9a). This helps maintain a uniform inter-electrode gap close to the discharge gap, thus enabling continuous spark generation at 68 nF. As the capacitance value increases, the material removed per spark also escalates, resulting in a more significant inter-electrode gap. Thus, no spark is generated until the required discharge gap is regained, resulting in a time gap between two successive sparks, refer to Fig. 8b–d. Small short-circuit phases are recorded at 120 nF capacitance, while at 150 nF, negligible machining is noticed due to excessive short-circuiting (see Fig. 8c,d). Due to the high energy per spark at this capacitance value, large debris is formed, which clogs the inter-electrode gap, resulting in a short circuit. This non-evacuation of the large debris leads to its re-solidification, as evident from Fig. 9c. The machined surface at 100 nF capacitance indicates uniform material removal and flushing debris, as visible in Fig. 9b. Based on these observations, a combination of 110 V and 100 nF is used in this study to fabricate arrayed micro-pillars on tungsten carbide turning tool inserts.

Stage II: Determination of cutting tool temperature and tool-chip contact area from turning experiments

The intimate contact between the fast-moving chips and the rake face makes tooltip temperature measurement very challenging. Therefore, an indirect approach is adopted in this study where thermocouples are embedded in the inserts at a distant location from the tooltip (see Fig. 4). The temperature measured by these thermocouples during the turning operation under dry, compressed air and wet conditions are depicted in Fig. 10. It is evident that the plain tool experiences a higher temperature compared to the textured tool, irrespective of the machining conditions. In dry condition a significant drop of 10.8% is witnessed, followed by 7.6% in compressed air and 4.2% in wet condition. This indicates the effectiveness of the textured tools in adverse conditions. The major causes of this temperature drop are restricted tool-chip contact area and enhanced heat dissipation through the rake face. Micro-pillar textured tools are capable of inducing higher curling to the flowing chips, which mitigates the adhering tendency of the freshly formed chip underside to the rake surface21,38. This aids in suppressing the additional heat generation in the seizure zone. Further, the increased surface area due to the fabrication of micro-pillars on the rake face enhances convective heat transfer from the tool to the surrounding air/CF.

Since the shearing of the chips in the seizure region is the major source of heat for the cutting tools, it is necessary to study the tool/ chip contact interface. To quantify the tool-chip contact interface, the rake faces of the used inserts were observed under a scanning electron microscope. The sticking contact area is quantified using Image J software, as demonstrated in Fig. 11a. The measured sticking region at the interface is plotted in Fig. 11b. In the case of plain tools, the least contact area is observed in compressed air condition, followed by wet and dry conditions. The high-pressure jet of compressed air, flowing opposite the direction of chip flow, uplifts the chip from its usual flow path and shortens the contact area. However, this phenomenon is non-visible in dry conditions since the air pressure is negligible. The low-pressure water jet led to a lower contact area than dry machining but significantly higher than compressed air condition. On the contrary, the contact area under dry and wet conditions has reduced substantially for the textured tools, while that in the case of compressed air is marginal. This highlights the adeptness of the textures to minimize the contact region by inducing tighter chip curling19. As the chip experiences the micro-gaps between the micro-pillars, it loses contact with the rake surface, leading to its deviation from the straight-line motion. As the chip touches the bottom of these micro-gaps and the edges of the subsequent micro-pillars, bending moments shall be exerted on the chip underside, subjecting it to curl further. The depth of the texture strongly influences the curling mechanism26. The mechanism of additional chip curling in textured tools is illustrated in Fig. 12. Alongside tighter chip curling, this textured pattern also facilitates enhanced cutting fluid penetration through its micro-gaps up to the cutting edge, which helps in retarding chip adhesion, as evident from textured tools under wet conditions. The effectiveness of textured tools in compressed air condition is minimal due to the already reduced contact area by the high-pressure jet. Figure 11b shows that textured tools and cutting conditions actively affect the tool-chip sticking contact area.

Stage III: Analysis of cutting tool temperature using CFD

This section presents the inverse estimation of tool tip temperature based on CFD analysis performed on the cutting tool inserts. The working model and the boundary conditions, as depicted in Fig. 5, form the basis of this analysis. A uniform heat flux is applied to the experimentally obtained sticking contact area (refer to Fig. 11), such that the simulated temperature becomes equal to the experimental tool temperature measured at the distant location A (refer to Figs. 4 and 10). To ensure the accuracy of the results, a mesh convergence study is performed to negate the effect of element size, the findings of which are compiled in Fig. 13. An element size of 30 µm was used for the tool insert and the control volume, while a finer element size of 10 µm was used for face meshing of the rake face due to the 20 µm depth of the textures. These element sizes have been chosen as a trade-off between accuracy and computational time. The total elements for the plain and textured tools were 49,86,623 and 65,51,084, respectively.

Inverse estimation of tool tip temperature

Based on the inverse temperature estimation approach mentioned above, heat flux in the range of 15–22 W/mm2 matched the experimental temperature, depending on the machining condition. Figure 14 shows the temperature contours of the tool section under various machining conditions. The experimentally obtained temperature is indicated by point A, which forms the reference for the study to fix the input heat flux over the experimentally obtained contact area on the rake face. The temperature at point B indicates the inversely estimated tool tip temperature. The estimated tool tip temperature for plain tools is significantly higher than the textured tools, irrespective of the machining condition. This resonates with the measured temperatures at point A. When compared with a plain tool, the tool tip temperature of the texture tool dropped by 7.5% under dry condition, while the temperature drop at point A for the same condition is about 10.8%. The higher temperature drop at the distant point A than at the tooltip (point B) suggests that the increased surface area due to the development of micro-pillars on the rake face enhances the convective heat dissipation through the rake face for the textured tools. However, this trend does not hold true for compressed air and wet conditions. This is because an external source like compressed air or cutting fluid has superior heat dissipation capability, making the textures less effective in these cases. However, the textured tools have shown a significant temperature drop of 8.1% and 13.3% at point A for compressed air and flood conditions, respectively. Therefore, it can be concluded that under dry condition, tool temperature is controlled by low tool-chip contact area and enhanced heat dissipation, whereas, for compressed air and wet conditions, it is majorly because of the lower tool-chip contact area.

Effect of micro-pillar texture size on tool temperature

Given the benefits associated with the micro-pillar textures developed on the rake face, it becomes necessary to study the effect of texture size on the tool temperature. From the basic knowledge of heat exchangers, it is well-known that long, closely-spaced fins of smaller diameter result in better heat dissipation from the hot body. However, the limitation associated with the existing manufacturing techniques to fabricate an array of micro-scale features makes this study challenging. Therefore, adopting a numerical approach becomes a feasible solution. A previous study revealed that increasing the depth of micro-pillars beyond 55 µm adversely affected their capabilities due to severe accumulation of the workpiece material in between the textures26. This restricts the use of higher-depth texture, which otherwise would enhance convective heat transfer. Moreover, the model developed in this study takes the tool-chip contact area as input, which is a function of texture shape and size. Thus, it should not be altered. Therefore, to explore the effect of texture size on tool temperature, the micro-pillar size was altered beyond the tool-chip contact area. Since textured tools were found to be most effective in improving convective heat transfer under dry conditions, only dry conditions are explored in the further part of the study.

Figure 15 indicates the effect of texture depth on the cutting tool temperature under dry condition. The diameter and pitch of the micro-pillar are kept constant at 300 µm and 100 µm respectively. It can be observed that increasing the depth of micro-pillars resulted in lower tool temperature due to improved convective heat transfer from the increased surface area of the rake face to the surrounding air. A temperature drop of 2.9% is achieved by increasing the texture depth from 20 to 100 µm.

The effect of change in diameter beyond the contact area at a constant depth and pitch of 100 µm each is presented in Fig. 16. Negligible improvement is observed in tool temperature. This is because the gap between two successive micro-pillars (pitch) is unaltered, which increases the number of micro-pillars but shifts them away from the machining region, thus making them ineffective.

The effect of pitch variation at a constant diameter of 50 µm and depth of 100 µm on tool temperature is present in Fig. 17. On decreasing the pitch from 200 to 50 µm a temperature drop of 2.3% is witnessed. This is because a smaller pitch increases the number of micro-pillars in the confined region of interest, providing a larger surface area for heat dissipation. However, further reducing the pitch to 25 µm adversely increased the tool temperature. This is probably due to extremely constrained passage between the micro-pillars, which would restrict the free flow of surrounding air through the textures up to the high-temperature region.

These effects of variation in micro-pillar depth, diameter, and inter-micro-pillar gap tool temperature are compiled in Fig. 18. An overall reduction of 5.1% in tool tip temperature is achieved by increasing the texture depth from 20 to 100 µm and decreasing the diameter and pitch from 300 to 50 µm and 200 µm to 50 µm, respectively.

Conclusions

This work examines the heat dissipation capability of micro-pillar textures fabricated using RµEDM on tungsten carbide inserts while turning Ti6Al4V alloys. CFD-based numerical simulation determined the tool tip temperature and distribution under Wet, dry, and compressed air conditions using experimentally measured tool temperature at a distant location and tool-chip contact. The key findings are:

-

An input voltage of 110 V and capacitance of 100 nF for the RµEDM were the most feasible combination for the arrayed micro-pillar fabrication process, based on spark frequency, discharge gap, and machined surface morphology.

-

The tool-chip contact is significantly reduced when turning with textured tools due to higher chip curling, as micro-pillars disrupt chip momentum.

-

Reduced heat influx to the tool due to reduced contact at the tool-chip interface and enhanced heat rejection from the increased surface area provided by the arrayed micro-pillar were the prime contributors to reduced tool temperature.

-

Closely spaced (50 µm) micro-pillars of smaller diameter (50 µm) and higher depth (100 µm) beyond the tool chip contact area reduced the tool tip temperature by 5.1% compared to large and widely spaced micro-pillars of lower depth. However, the inter-micro-pillar gap should not be too low to hinder the flow of fluid through it, as observed in the 25 µm pitch gap.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Trent, E. M. Heat in metal cutting. In Metal cutting 4th edn (eds Edward, M. & Wright, P. K.) (Elsevier, 2000).

Armendia, M., Garay, A., Iriarte, L. M. & Arrazola, P. J. Comparison of the machinabilities of Ti6Al4V and TIMETAL® 54M using uncoated WC-Co tools. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 210, 197–203. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmatprotec.2009.08.026 (2010).

Taylor, F. W. On the art of cutting metals. Trans. Am. Soc. Mech. Eng. 28, 31–279. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.4060388 (1906).

Groover, M. P. Fundamentals of Modern Manufacturing: Material, Processes, and Systems (Wiley, 2010).

Goindi, G. S. & Sarkar, P. Dry machining: a step towards sustainable machining – Challenges and future directions. J. Clean Prod. 165, 1557–1571. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.07.235 (2017).

Jianxin, D., Tongkun, C., Xuefeng, Y. & Jianhua, L. Self-lubrication of sintered ceramic tools with CaF2 additions in dry cutting. Int. J. Mach. Tools Manuf. 46, 957–963. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmachtools.2005.07.047 (2006).

Jaffery, S. I. & Mativenga, P. T. Assessment of the machinability of Ti-6Al-4V alloy using the wear map approach. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 40, 687–696. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00170-008-1393-9 (2009).

Bart, J. C. J., Gucciardi, E. & Cavallaro, S. Environmental life-cycle assessment (LCA) of lubricants. Biolubricants https://doi.org/10.1533/9780857096326.527 (2013).

Bennett, E. O. Water based cutting fluids and human health. Tribol. Int. 16, 133–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/0301-679X(83)90055-5 (1983).

Deswal, N. & Kant, R. Machinability and surface integrity analysis of magnesium AZ31B alloy during laser assisted turning. J. Manuf. Process. 101, 527–545. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmapro.2023.06.022 (2023).

Rahman Rashid, R. A., Sun, S., Wang, G. & Dargusch, M. S. The effect of laser power on the machinability of the Ti-6Cr-5Mo-5V-4Al beta titanium alloy during laser assisted machining. Int. J. Mach. Tools Manuf. 63, 41–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmachtools.2012.07.006 (2012).

Airao, J., Nirala, C. K., Bertolini, R., Krolczyk, G. M. & Khanna, N. Sustainable cooling strategies to reduce tool wear, power consumption and surface roughness during ultrasonic assisted turning of Ti-6Al-4V. Tribol. Int. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.triboint.2022.107494 (2022).

Yang, Z., Zhu, L., Zhang, G., Ni, C. & Lin, B. Review of ultrasonic vibration-assisted machining in advanced materials. Int. J. Mach. Tools Manuf. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmachtools.2020.103594 (2020).

Kawasegi, N., Sugimori, H., Morimoto, H., Morita, N. & Hori, I. Development of cutting tools with microscale and nanoscale textures to improve frictional behavior. Precis. Eng. 33, 248–254. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.precisioneng.2008.07.005 (2009).

Durairaj, S., Guo, J., Aramcharoen, A. & Castagne, S. An experimental study into the effect of micro-textures on the performance of cutting tool. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 98, 1011–1030. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00170-018-2309-y (2018).

Orra, K. & Choudhury, S. K. Tribological aspects of various geometrically shaped micro-textures on cutting insert to improve tool life in hard turning process. J. Manuf. Process. 31, 502–513. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmapro.2017.12.005 (2018).

Sugihara, T. & Enomoto, T. Performance of cutting tools with dimple textured surfaces: A comparative study of different texture patterns. Precis. Eng. 49, 52–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.precisioneng.2017.01.009 (2017).

Liu, J. L. & Feng, X. Q. On elastocapillarity: A review. Acta Mech. Sinica/Lixue Xuebao 28, 928–940. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10409-012-0131-6 (2012).

Saraf, G. & Nirala, C. K. Experimental investigation of micro-pillar textured WC inserts during turning of Ti6Al4V under various cutting fluid strategies. J. Manuf. Process. 113, 61–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JMAPRO.2024.01.065 (2024).

Saraf, G. & Nirala, C. K. Novel texture pattern on WC inserts fabricated using reverse-μEDM for enhanced cutting of Ti6Al4V. Manuf. Lett. 36, 72–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mfglet.2023.04.001 (2023).

Sawant, M. S., Jain, N. K. & Palani, I. A. Influence of dimple and spot-texturing of HSS cutting tool on machining of Ti-6Al-4V. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 261, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmatprotec.2018.05.032 (2018).

Abukhshim, N. A., Mativenga, P. T. & Sheikh, M. A. Heat generation and temperature prediction in metal cutting: A review and implications for high speed machining. Int. J. Mach. Tools Manuf. 46, 782–800. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmachtools.2005.07.024 (2006).

Stephenson, D. A. Tool-work thermocouple temperature measurements—Theory and implementation issues. J. Manuf. Sci. E. T. ASME 115, 432–437. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.2901786 (1993).

Santos, M. C., Araújo Filho, J. S., Barrozo, M. A. S., Jackson, M. J. & Machado, A. R. Development and application of a temperature measurement device using the tool-workpiece thermocouple method in turning at high cutting speeds. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 89, 2287–2298. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00170-016-9281-1 (2017).

Xie, J., Luo, M. J., Wu, K. K., Yang, L. F. & Li, D. H. Experimental study on cutting temperature and cutting force in dry turning of titanium alloy using a non-coated micro-grooved tool. Int. J. Mach. Tools Manuf. 73, 25–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmachtools.2013.05.006 (2013).

Saraf, G., Sutrave, N. H. & Nirala, C. K. Sustainable approach for machining of Ti6Al4V using micro-pillar textured turning tool insert. Sustain. Mater. Technol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.susmat.2024.e00929 (2024).

Chen, W. C., Tsao, C. C. & Liang, P. W. Determination of temperature distributions on the rake face of cutting tools using a remote method. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 24, 161–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0735-1933(97)00002-X (1997).

Su, M. Y., Wang, D. R., Wang, Q., Jiang, M. Q. & Dai, L. H. Towards Salomon’s hypothesis via ultra-high-speed cutting Ti-6Al-4V alloy. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 129, 5679–5690. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00170-023-12668-4 (2023).

Dearnley, P. A. New technique for determining temperature distribution in cemented carbide cutting tools. Met. Technol. 10, 205–214. https://doi.org/10.1179/030716983803291578 (1983).

Oezkaya, E., Beer, N. & Biermann, D. Experimental studies and CFD simulation of the internal cooling conditions when drilling Inconel 718. Int. J. Mach. Tools Manuf. 108, 52–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmachtools.2016.06.003 (2016).

López De Lacalle, L. N., Angulo, C., Lamikiz, A. & Sánchez, J. A. Experimental and numerical investigation of the effect of spray cutting fluids in high speed milling. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 172, 11–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmatprotec.2005.08.014 (2006).

Singh, R. & Sharma, V. CFD based study of fluid flow and heat transfer effect for novel turning tool configured with internal cooling channel. J. Manuf. Process. 73, 164–176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmapro.2021.10.063 (2022).

Fang, Z. & Obikawa, T. Turning of Inconel 718 using inserts with cooling channels under high pressure jet coolant assistance. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 247, 19–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmatprotec.2017.03.032 (2017).

Kishore, H., Nirala, C. K. & Agrawal, A. Feasibility demonstration of µEDM for fabrication of arrayed micro pin-fins of complex cross-sections. Manuf. Lett. 23, 14–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mfglet.2019.11.005 (2020).

Raza, S., Nadda, R. & Nirala, C. K. Real-time data acquisition and discharge pulse analysis in controlled RC circuit based Micro-EDM. Microsyst. Technol. 29, 359–376. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00542-023-05432-x (2023).

Li, T., Wu, T., Ding, X., Chen, H. & Wang, L. Design of an internally cooled turning tool based on topology optimization and CFD simulation. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 91, 1327–1337. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00170-016-9804-9 (2017).

Raza, S., Nadda, R. & Nirala, C. K. Analysis of discharge gap using controlled RC based circuit in µEDM process. J. Inst. Eng. India Ser. C 103, 21–27. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40032-021-00711-w (2022).

Saraf, G., Imam, S. & Nirala, C. K. Machinability analysis of additively manufactured Ti6Al4V using micro-pillar textured tool under various cutting fluid strategies. Wear https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wear.2024.205514 (2024).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Science and Engineering Research Board (SERB), DST India, for the financial support (CRG/2022/008153) to carry out this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Gaurav Saraf: Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization, Writing—original draft. Gaurav Sharma: Data acquisition and curation. Rahul Kumar: Numerical simulation. Chandrakant K. Nirala: Writing—review and editing, Supervision, Methodology, Conceptualization, Funding acquisition.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Saraf, G., Sharma, G., Kumar, R. et al. Experimental and numerical investigation on heat dissipation capability of micro-pillar textured cutting tools. Sci Rep 15, 12282 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96124-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96124-1

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Role of dual textured tools in MQL turning operation

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Sustainability and machinability in hard turning under MQL conditions using nanoparticle-enriched vegetable-based fluid: an integrated assessment

The International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology (2025)