Abstract

Depression and obesity are common chronic diseases in modern society. Meta-analyses consistently reveal a bidirectional relationship: individuals with depression have a higher risk of obesity, while obese individuals are more prone to depression. High-fat diet (HFD) consumption is a risk factor of obesity. However, the impact of depression on obesity and the underlying mechanisms remains unclear. We aim to assess the impact of a long-term depressive state throughout adulthood on body weight changes induced by HFD, and whether HFD affects depressive state in mice. We established a depression mouse model using a Chronic Unpredictable Mild Stress (CUMS) paradigm. Following the stress period, male mice were fed with a normal diet or a HFD for seven weeks prior to behavioral tests and body weight measurements. Our results suggest that exposure to CUMS initially accelerated weight gain in mice; however, it did not significantly affect final body weight or white adipose tissue weight. Additionally, while HFD did not significantly impact measures of depression-like behavior in CUMS mice but tended to induce depression-like behavior in control mice. Overall, contrary to clinical observations, our findings revealed that a depressive state did not significantly affect the development of obesity in mice, nor did HFD significantly exacerbate depressive-like behaviors in mice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Depression is a common mental disorder characterized by persistent feelings of sadness, loss of interest in activities, inability to experience pleasure, and various other symptoms, including weight changes. Obesity, defined as excessive fat accumulation, poses significant health risks, such as heart disease, diabetes, and cancer1. The co-occurrence of depression and obesity is widely observed, with numerous studies establishing their bidirectional relationship2,3,4. For instance, a recent study indicated that obesity increases the risk to lifetime depression by 55%, while depression increases the risk of becoming obese by 58%5.

Chronic stress plays a crucial role in both depression and obesity, serving as a key factor that bridges the two conditions. One of the most prominent characteristics of a depressive state is the increased level of cortisol, which is elevated due to the perception of stress. Stress activates the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, leading to the secretion of cortisol, which increases motivation to eat by reducing the brain’s sensitivity to leptin and stimulating neuropeptide Y, a key regulator of feeding behavior6,7. In addition, cortisol directly promotes fat deposition, particularly in the abdominal region. Evidence from Cushing’s disease patients, who exhibit excessive cortisol levels, demonstrates that treatments aimed at lowering cortisol can alleviate abdominal obesity8. Behaviorally, individuals under stress tend to consume high-sugar, high-fat, and high-calorie food as a form of emotional regulation9,10. The combination of these physiological effects and stress-induced behavioral changes collectively contributes to excessive weight gain and obesity.

Dietary fat intake is strongly associated with the development of obesity11. Beyond its role in obesity, substantial evidence links high-fat diet (HFD) consumption to a range of neuropsychiatric disorders, including mood disorders, developmental disorders, and neurodegenerative diseases11,12,13. Our recent study found that 23 weeks of HFD consumption led to depression-like behaviors and reduced hippocampal volume in mice14. Similarly, research has shown that mice fed an HFD throughout adulthood exhibited more anxiety-like, depression-like, and disruptive social behaviors compared to those on a normal diet15. Interestingly, another study found that a three-month HFD resulted in a significant increase in anxiety-like behavior in adult mice, but not in aged mice, suggesting that adulthood is a period of heightened susceptibility to diet-induced adverse neurobehavioral effects16.

Building on these findings, the present study aims to explore the interaction between depressive states and high-fat diet consumption in adult mice. Using the Chronic Unpredictable Mild Stress (CUMS) mouse model of depression, we investigate whether a depressive state in adulthood influences HFD-induced body weight changes and whether HFD impacts the depressive state.

Methods

Animals

Eight-week-old C57BL/6J male mice were used and were purchased from GemPharmatech (Nanjing, China) and Charles River (Beijing, China). Male mice were used to avoid possible physiological variabilities in female mice (e.g., hormonal fluctuations in the estrous cycle). Mice were housed 4–5 per cage, under a 12-h light/dark cycle with free access to food and water. Stress intervention commenced after a 1-week habituation period. This study adhered to the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. The protocol was approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of Shanghai Medical College, Fudan University, Shanghai, China (20120302-107). The study was conducted in accordance with ARRIVE guidelines.

Experimental design

Mice were randomly divided into the control group (n = 18) and the CUMS group (n = 18). The sample size was chosen to ensure sufficient randomization and to account for potential animal loss in depression mouse model. The CUMS group underwent 18-week of chronic and unpredictable mild stress, while the control group received no treatment17,18,19. Behavioral tests were carried out on mice in both groups following the 18-week CUMS period. The open field test (OFT), tail suspension test (TST), and forced swim test (FST) were conducted in sequence with 2-hour intervals using standard protocols to confirm their depressive states20,21. Details are provided in Fig. 1. After cessation of the stress stimuli, each group was further randomly split into two groups, with mice fed either a normal chow diet (ND, containing 10% fat calories) or HFD (containing 60% fat calories) (D12492, Research Diets) for 7 weeks, with each mouse provided a fixed amount of food (5 g/mouse/day). No substantial leftover food was observed. This resulted in four groups: Control_ND group (n = 9), Control_HFD group (n = 9), CUMS_ND group (n = 9) and CUMS_HFD group (n = 9). Weekly body weight was measured to monitor the onset and progression of obesity. Behavioral tests were repeated after the final day of dietary intervention. Subsequently, all animals were euthanized via cervical dislocation, and white adipose tissue (WAT) was weighed (Fig. 1).

Experimental procedures. Eight-week-old C57BL/6J male mice were randomly divided into the CUMS group (n = 18) and control group (n = 18). The CUMS group underwent 18-week of chronic and unpredictable mild stress, while the control group received no treatment. Behavioral tests were carried out on mice in both groups following the 18-week period. After cessation of the stress stimuli, each group was further randomly split into two groups, fed either a normal chow or high-fat diet for 7 weeks. Weekly body weight was measured. Behavioral tests were repeated after the dietary intervention, followed by euthanasia and white adipose tissue collection. CUMS, chronic unpredictable mild stress; HFD, high-fat diet; ND, normal diet.

CUMS procedure

CUMS involves subjecting animals to various mild stressors at random times and is widely used to establish depression models. Stressors included food deprivation (24 h), water deprivation (24 h), cage tilt (45°, 24 h), wet bedding (24 h), cold water swimming (10 °C, 5 min), overnight illumination, restraint (2 h), vibrating cage (40 rpm, 5 min), and bedding removal (24 h). Mice were exposed to one stressor daily at random times.

FST

In this test, mice were placed into a transparent cylindrical container measuring 100 mm in diameter and 300 mm in height, filled with water (22 ± 2 ℃) at a depth that prevented them from touching the bottom or escaping so that they were forced to swim. A video camera started recording the mice for 6 min upon placement in the water, with the last 4 min used for measuring their total immobility time. Immobility was defined as the animal’s absence of active swimming or struggle, except for the necessary actions to keep its head above water.

TST

In the TST, mice had their tails fixed to a stand using medical tape at 1–2 cm from the tail tip, positioning their heads downward approximately 5 cm from the ground. The tape prevented the mice from climbing or breaking away. A video camera recorded each mouse’s 6-minute suspension, with the last 4 min used to measure their total immobility time. Immobility is defined as the absence of movement, including swinging of the front and rear limbs or twisting of the body, of the suspended animal.

OFT

In the OFT, mice were placed in the central area (250 mm × 250 mm × 500 mm) of an open square field (500 mm × 500 mm × 500 mm), and the total distance travelled in the field and the time spent in each area were observed for each mouse to reflect its exercise capacity and anxiety state. Mice were allowed to explore freely for two minutes to familiarize themselves with the environment before video recording began for five minutes. An automatic tracking system counted various indicators observed during the test. The field was cleaned and wiped with alcohol between each test to reduce the effect of the previous mouse’s scent on the experimental results.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted in GraphPad Prism version 8.30, with results presented as mean ± standard deviation (mean ± SD). T-test was used to compare the data between two groups, and two-way ANOVA with Turkey’s test was used to compare the data of multiple groups. If the results were statistically different, Fisher’s LSD test was used for post hoc analysis. P < 0.05 indicated that the difference was statistically significant.

Results

Following 18 weeks of CUMS exposure, the CUMS group exhibited increased immobility time after exposure to CUMS compared with the control group in both TST (P = 0.0344) and FST (P = 0.0014) (Fig. 2a, b). Moreover, in the OFT, mice in the CUMS group showed a reduced total distance and time in the central zone (Figure S1 a, b, P = 0.0004 and 0.0008, respectively). These results indicate a successful depressive-like behavior induction by CUMS. Following 7 weeks feeding with either ND or HFD, mice exposed to CUMS continued to exhibit depressive-like behavior despite cessation of the stimulus (Fig. 2d, Figure S1 c, CUMS_ND vs. Control_ND, P < 0.0001, P = 0.0106, respectively). Moreover, the behavior of mice in the CUMS_HFD group did not change significantly compared with the CUMS_ND group (Fig. 2c, Figure S1 d), suggesting that HFD did not affect the behavior of mice with pre-existing depression. In contrast, mice in control group showed an increase in immobility time in the FST (Fig. 2d, P = 0.0331) after exposure to HFD compared to ND, indicating that HFD can induce depressive-like behavior in normal mice.

CUMS induced depressive-like behavior, but HFD did not affect the behavior in mice exhibiting depressive-like behaviors. (a–b) Behavioral tests results of mice after CUMS for 18 weeks. (n = 18 in each group) (a) Immobility time in the TST. (b) Immobility time in the FST. (c–d) Behavioral tests results of mice after CUMS and dietary intervention (fed with HFD or ND) for 7 weeks. (n = 9 in each group). (c) Immobility time in the TST. (d) Immobility time in the FST. All data is presented as mean ± SD. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001. CUMS, chronic unpredictable mild stress; FST, forced swim test; HFD, high-fat diet; ND, normal diet; SD, standard deviation; TST, tail suspension test.

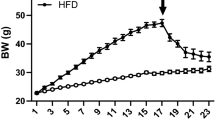

The mice lost weight after exposure to CUMS (Fig. 3a, b, P < 0.0001). After random group allocation, body weight was measured across the four groups, and no significant difference was observed within the CUMS or control groups. After the diet intervention, mice exhibiting depressive-like symptoms fed with ND still showed lower body weight than that of mice in control group (Fig. 3c, CUMS_ND vs. Control_ND, P = 0.0120). As expected, HFD induced a significant increase in body weight (Fig. 3c, Control_ND vs. Control_HFD, P = 0.0006; CUMS_ND vs. CUMS_HFD, P < 0.0001). However, no significant difference in body weight was observed between HFD-fed mice in control or CUMS groups. Weekly weight gain analysis revealed that mice exhibiting depressive-like symptoms had significantly higher weight gain than control mice in the first week (Fig. 3d, CUMS_ND vs. Control_ND, P = 0.0183, CUMS_HFD vs. Control_HFD, P = 0.0002). In the second week, the weight gain of mice in the CUMS_HFD group remained higher than that of those in the Control_HFD group, though not significantly (Fig. 3d, P = 0.0514), while there was no difference between the CUMS_ND group and the Control_ND group (Fig. 3d, P = 0.9274). This suggests that the depressive state of mice accelerated their obesity development, but not significantly. Since the inguinal WAT and the epididymal WAT are the major organs for storing fat22, we measured their weights in mice, and discovered that HFD induced significant increases in both types of WAT (Fig. 3e, f, P < 0.0001). However, a depressive state did not affect HFD-induced weight gain in inguinal WAT (Fig. 3e) but instead decreased that in epididymal WAT (Fig. 3f, CUMS_HFD vs. Control_HFD, P = 0.0155). These findings collectively demonstrate that depressive state can accelerate early weight gain in adult mice during HFD consumption but do not significantly alter final body weight or white adipose tissue mass.

Depressive state did not affect the body weight of HFD-fed mice but accelerated the process of obesity. (a) The body weight of mice after CUMS for 18 weeks (n = 18 in each group). (b) The body weight of mice after CUMS for 18 weeks and prior to dietary intervention (n = 9 in each group). (c) The body weight of mice after CUMS and 7-week HFD (n = 9 in each group). (d) The weekly weight change of mice after CUMS and 7-week HFD (n = 9 in each group). (e) The weight of iWAT after CUMS and 7-week HFD (n = 6 in each group). (f) The weight of eWAT after CUMS and 7-week HFD (n = 6 in each group). All data are presented as mean ± SD. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001. CUMS, chronic unpredictable mild stress; eWAT, epididymal white adipose tissue; HFD, high-fat diet; iWAT, inguinal white adipose tissue; ND, normal diet; SD, standard deviation.

Discussion

This study used long-term CUMS to establish a depression mouse model, followed by dietary intervention to observe behavioral and body weight changes after prolonged consumption of HFD. While CUMS is widely used to establish animal depression models23,24, CUMS alone may cause body weight reduction25,26,27. Meta-analysis also indicated differential sensitivity to stress exposure duration, with longer exposure leading to stronger behavioral effects23. Once established, these changes can be maintained by continued application of CUMS for three months or longer, and persists for 2–3 weeks after the termination of stress28. Therefore, to better induce a long-term depressive state in mice after the CUMS modeling, we extended the stress exposure up to 18 weeks and stopped the stimulation in the subsequent 7-week dietary intervention. However, this raises an issue that the mice had reached 35 weeks (between mature and middle-aged) at the end of the dietary intervention, notably older than mice in most of the relevant translational studies using 8–10 weeks of duration29. Therefore, references and comparisons with relevant studies should be approached with caution, considering this age difference.

In this study, we used male animals to minimize variability associated with hormonal fluctuations inherent in female reproductive cycles, which can influence stress responses and metabolic parameters. Previous research indicates that male and female rodents may exhibit different susceptibilities to stress-induced metabolic changes, potentially confounding the results30. By focusing on male subjects, we aimed to reduce hormonal variability and obtain clearer insights into the mechanisms under investigation. We acknowledge that excluding female animals limits the generalizability of our findings, and future studies should incorporate both sexes to provide a more comprehensive understanding.

The behavioral tests demonstrated that CUMS throughout adulthood induced obvious depressive-like behaviors in mice, which persisted 7 weeks after end of the stimulus. Subsequent HFD feeding showed no significant impact on their pre-existing depression. Interestingly, some studies have found that individuals with a body mass index ≥ 25 achieve a poorer clinical response to antidepressant treatment31, and that treatment-resistant depression is associated with baseline obesity32. Therefore, the effect of HFD on the depressive state might be reflected by the response to conventional antidepressant therapy rather than the severity of depression.

Anxiety frequently co-occurs with depression, with a significant proportion of individuals exhibiting both conditions33. In mouse models, anxiety-like behavior is often assessed using the OFT; however, its interpretation is complex, as the test can reflect both anxiety- and depression-like states34. In our study, CUMS mice exhibited reduced total distance traveled and decreased time in the central zone (Figure S1). Previous studies in CUMS-induced mice have demonstrated decreased total distance traveled, along with other depressive phenotypes such as weight loss, reduced sucrose preference, and impaired exploratory behavior in cognitive tests35. The locomotor reduction observed in our CUMS mice may indicate either anxiety- or depression-like behavior. Additional behavioral assessments, such light-dark box test, are needed to clarify the role of HFD in anxiety.

To explore whether mice exhibiting depressive-like symptoms had increased susceptibility to obesity, we monitored their body weight changes after HFD. We discovered that the mice did not become more obese but gained weight more quickly in the first two weeks, contradicting some clinical findings. However, inconsistencies in the induction of obesity by depression have been noted in clinical studies, suggesting that this correlation may be limited to specific depression subtypes36,37. Therefore, this difference may be related to the choice of the depression model. Furthermore, our study focused solely on body weight changes and did not evaluate potential metabolic alterations in depressed mice. For the preclinical modeling of depression, anhedonia-related tests (e.g., sucrose preference test) should be included, or spatial memory tasks (e.g., Morris Water Maze) could add to the validity of the model. Moreover, incorporating neurobiological correlates like plasma corticosterone levels or GC receptor expression analysis could enhance the construct validity of the model. In future studies, a more comprehensive evaluation system could be used to further explore this aspect, including the evaluation of hippocampal pyramidal neuron dendritic length and arborization in Golgi-stained slices, or the measurement of catecholamine tissue levels using high-performance liquid chromatography. Despite these limitations, our study is the first to observe that mice in a depressed state throughout adulthood exhibit faster weight gain in the early stages after prolonged HFD consumption.

Conclusion

Our study demonstrates the complex interaction between depressive states and HFD in influencing obesity and behavior in mice. While depressive states accelerate early weight gain in adult mice during HFD consumption, they do not significantly alter final body weight or white adipose tissue mass. Interestingly, HFD induces depressive-like behaviors in normal mice, but does not exacerbate depressive symptoms in those already depressed. These findings highlight the nuanced relationship between mental health and diet, suggesting that while depressive states may predispose individuals to rapid weight gain, the mechanisms linking depression and obesity may differ depending on the context. Further studies are needed to explore the underlying metabolic and neurobiological pathways involved in this interaction.

Data availability

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Abbreviations

- CUMS:

-

Chronic unpredictable mild stress

- FST:

-

Forced swim test

- HFD:

-

High-fat diet

- ND:

-

Normal diet

- OFT:

-

Open field test

- TST:

-

Tail suspension test

- WAT:

-

White adipose tissue

References

Panuganti, K. K., Nguyen, M. & Kshirsagar, R. K. in StatPearls (StatPearls Publishing Copyright © 2024, StatPearls Publishing LLC., (2024).

Lasselin, J. & Capuron, L. Chronic low-grade inflammation in metabolic disorders: Relevance for behavioral symptoms. Neuroimmunomodulation 21, 95–101. https://doi.org/10.1159/000356535 (2014).

Dawes, A. J. et al. Mental health conditions among patients seeking and undergoing bariatric surgery: A meta-analysis. Jama 315, 150–163. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2015.18118 (2016).

de Wit, L. et al. Depression and obesity: A meta-analysis of community-based studies. Psychiatry Res. 178, 230–235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2009.04.015 (2010).

Luppino, F. S. et al. Overweight, obesity, and depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 67, 220–229. https://doi.org/10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.2 (2010).

Sinha, R. & Jastreboff, A. M. Stress as a common risk factor for obesity and addiction. Biol. Psychiatry 73, 827–835. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.01.032 (2013).

Jéquier, E. Leptin signaling, adiposity, and energy balance. Ann. N Y Acad. Sci. 967, 379–388. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb04293.x (2002).

Tomiyama, A. J. Stress and obesity. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 70, 703–718. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010418-102936 (2019).

Adam, T. C. & Epel, E. S. Stress, eating and the reward system. Physiol. Behav. 91, 449–458. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.04.011 (2007).

Torres, S. J. & Nowson, C. A. Relationship between stress, eating behavior, and obesity. Nutrition 23, 887–894. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nut.2007.08.008 (2007).

Chen, J. et al. New insights into the mechanisms of high-fat diet mediated gut microbiota in chronic diseases. Imeta 2, e69. https://doi.org/10.1002/imt2.69 (2023).

Cordner, Z. A. & Tamashiro, K. L. Effects of high-fat diet exposure on learning & memory. Physiol. Behav. 152, 363–371. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2015.06.008 (2015).

Dutheil, S., Ota, K. T., Wohleb, E. S., Rasmussen, K. & Duman, R. S. High-Fat diet induced anxiety and anhedonia: Impact on brain homeostasis and inflammation. Neuropsychopharmacology 41, 1874–1887. https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2015.357 (2016).

Hu, J. et al. 1-Methyltryptophan treatment ameliorates high-fat diet-induced depression in mice through reversing changes in perineuronal nets. Transl Psychiatry 14, 228. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-024-02938-4 (2024).

Zhuang, H. et al. Long-term high-fat diet consumption by mice throughout adulthood induces neurobehavioral alterations and hippocampal neuronal remodeling accompanied by augmented microglial lipid accumulation. Brain Behav. Immun. 100, 155–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2021.11.018 (2022).

Kesby, J. P. et al. Spatial cognition in adult and aged mice exposed to high-fat diet. PloS One 10, e0140034. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0140034 (2015).

Kingir, E., Sevinc, C. & Unal, G. Chronic oral ketamine prevents anhedonia and alters neuronal activation in the lateral Habenula and nucleus accumbens in rats under chronic unpredictable mild stress. Neuropharmacology 228, 109468. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropharm.2023.109468 (2023).

Pothion, S., Bizot, J. C., Trovero, F. & Belzung, C. Strain differences in sucrose preference and in the consequences of unpredictable chronic mild stress. Behav. Brain Res. 155, 135–146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbr.2004.04.008 (2004).

Wang, L. et al. Supplementation with soy isoflavones alleviates depression-like behaviour via reshaping the gut microbiota structure. Food Funct. 12, 4995–5006. https://doi.org/10.1039/d0fo03254a (2021).

Zhang, S. et al. Regulation of indoleamine 2, 3-dioxygenase in hippocampal microglia by NLRP3 inflammasome in lipopolysaccharide-induced depressive-like behaviors. Eur. J. Neurosci. 52, 4586–4601. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejn.15016 (2020).

Jeon, S. A. et al. NLRP3 inflammasome contributes to Lipopolysaccharide-induced depressive-like behaviors via indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase induction. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 20, 896–906. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijnp/pyx065 (2017).

Ji, L. et al. AKAP1 deficiency attenuates diet-induced obesity and insulin resistance by promoting fatty acid oxidation and thermogenesis in brown adipocytes. Adv. Sci. (Weinh) 8, 2002794–2002794. https://doi.org/10.1002/advs.202002794 (2021).

Antoniuk, S., Bijata, M., Ponimaskin, E. & Wlodarczyk, J. Chronic unpredictable mild stress for modeling depression in rodents: Meta-analysis of model reliability. Neurosci. Biobehav Rev. 99, 101–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2018.12.002 (2019).

Hu, C. et al. Re-evaluation of the interrelationships among the behavioral tests in rats exposed to chronic unpredictable mild stress. PloS One 12, e0185129. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0185129 (2017).

Su, W. J. et al. NLRP3 gene knockout blocks NF-κB and MAPK signaling pathway in CUMS-induced depression mouse model. Behav. Brain Res. 322, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbr.2017.01.018 (2017).

Ding, F. et al. Effect of Xiaoyaosan on colon morphology and intestinal permeability in rats with chronic unpredictable mild stress. Front. Pharmacol. 11, 1069. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2020.01069 (2020).

Zhang, M. et al. Matrine alleviates depressive-like behaviors via modulating microbiota-gut-brain axis in CUMS-induced mice. J. Translational Med. 21 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-023-03993-z (2023).

Willner, P., Muscat, R. & Papp, M. Chronic mild stress-induced anhedonia: A realistic animal model of depression. Neurosci. Biobehav Rev. 16, 525–534. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0149-7634(05)80194-0 (1992).

Flurkey, K. et al. J. in The Mouse in Biomedical Research (Second Edition) (eds James G. Fox Academic Press, 637–672 (2007).

Markov, D. D. & Novosadova, E. V. Chronic unpredictable mild stress model of depression: possible sources of poor reproducibility and latent variables. Biology (Basel) 11 https://doi.org/10.3390/biology11111621 (2022).

Kloiber, S. et al. Overweight and obesity affect treatment response in major depression. Biol. Psychiatry 62, 321–326. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.10.001 (2007).

Woo, Y. S., Seo, H. J., McIntyre, R. S. & Bahk, W. M. Obesity and its potential effects on antidepressant treatment outcomes in patients with depressive disorders: A literature review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 17 https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms17010080 (2016).

Ren, L. et al. The incidence and influencing factors of recent suicide attempts in major depressive disorder patients comorbid with moderate-to-severe anxiety: A large-scale cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry. 25, 31. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-025-06472-5 (2025).

Bao, X., Qi, C., Liu, T. & Zheng, X. Information transmission in mPFC-BLA network during exploratory behavior in the open field. Behav. Brain Res. 414, 113483. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbr.2021.113483 (2021).

Hao, W. et al. Gut dysbiosis induces the development of depression-like behavior through abnormal synapse pruning in microglia-mediated by complement C3. Microbiome 12(34). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40168-024-01756-6 (2024).

Roberts, R. E., Deleger, S., Strawbridge, W. J. & Kaplan, G. A. Prospective association between obesity and depression: Evidence from the Alameda County study. Int. J. Obes. Relat. Metab. Disord. 27, 514–521. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ijo.0802204 (2003).

Patist, C. M., Stapelberg, N. J. C., Toit, D., Headrick, J. P. & E. F. & The brain-adipocyte-gut network: Linking obesity and depression subtypes. Cogn. Affect. Behav. Neurosci. 18, 1121–1144. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13415-018-0626-0 (2018).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the funding support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Number 31871029).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.H., S.Z., H.W., and H.X. performed formal analysis and investigation. J.H., S.Z., H.W., X.L., M.T. and H.X. performed data curation. J.H., X.L., M.T., and M.W. contributed to visualization. X.L., M.T., M.W., M.L., and L.W. wrote the original draft, reviewed and edited the manuscript. M.Z., X.C., and Q.L. conceptualized the study. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The protocol was approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of Shanghai Medical College, Fudan University, Shanghai, China (20120302-107).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hu, J., Li, X., Tang, M. et al. Interaction between depressive state and high-fat diet and its impact on behavioral and body weight changes in male mice. Sci Rep 15, 12170 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96268-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96268-0