Abstract

Epoxy adhesives are widely used as structural adhesives distinguished by a significant degree of cross-linking, resulting in their brittle characteristics. Some specialized applications require improved thermal stability and adhesive strength. The incorporation of zinc oxide nanoparticles into a core–shell rubber (CSR) structure composed of poly(butyl acrylate-allyl methacrylate) core and poly(methyl methacrylate-glycidyl methacrylate) shell will enhance the adhesion, toughness, and thermal stability of epoxy adhesives. We synthesized CSR particles using a two-stage emulsion polymerization method, characterizing them through Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), scanning electron microscopy (SEM), transmission electron microscopy (TEM), and differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) analyses. We synthesized epoxy adhesives with different CSR particles ratios (1.25, 2.5, and 3.75 phr) and zinc oxide nanoparticles (1, 2, and 5 phr) using mechanical stirring and ultrasonication (a two-step mixing process) to enhance dispersion. We cured the epoxy adhesive samples for 7 days for tensile tests and 2 days for lap shear tests at room temperature. We employed the tensile and lap shear tests to assess the mechanical properties of the samples. The samples underwent thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) to assess their thermal stability. We assessed the fracture surface of the optimum samples using field-emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM). We utilized design-of-experiments (DOE) and artificial neural network (ANN) approaches to model the mechanical properties. The outcomes of FTIR, SEM, TEM and DCS analyses validated the successful synthesis of CSR particles. The tensile test findings on the dumbbell-shaped samples show a 51%, 30%, and 218% enhancement in tensile strength, modulus, and toughness for the samples containing 2.5 phr CSR particles and 2 phr zinc oxide nanoparticles, respectively. Furthermore, the lap shear tests revealed that the addition of 3.75 phr CSR particles and 5 phr zinc oxide nanoparticles increased the shear strength to 19.5 MPa. This is 127% higher than the pure epoxy. The TGA data indicated that both additions improved the thermal stability of the pure epoxy. Additionally, the predictions of shear strength, toughness, tensile modulus, and tensile strength by DOE and ANN were very close to the experimental results (R2adj > 0.95 for DOE and MREave < 3.2 for ANN).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Advantages of the adhesives compared to the mechanical joints, as well as the development of composite materials, have increased the demand for the production of adhesives1,2,3. Epoxy adhesives have found extensive industrial applications due to their intrinsic properties and compatibility with a wide range of materials, allowing for their modification or improvement4,5,6. Some of their key features include: high resistance against chemical agents, high corrosion resistance, the ability to cure in an ambient environment, slight shrinkage during curing, great strength, electrical insulation, and excellent adhesion7,8,9. High cross-linking ability in epoxy resins results in the formation of a network structure with high strength; this network structure, however, results in the high brittleness of epoxy after its curing10,11. Numerous methods exist to resolve this issue, including the use of thermoplastics12, nanoparticles13, liquid rubbers14, mixing with other resins15, and other approaches. The most common method involves using toughening agents. CSRs are a new class of toughening agents with a great impact on the improvement of toughness. Lower losses in mechanical properties and thermal stability are among the major advantages of these toughening agents. They can also enhance the mentioned properties16,17,18. The agglomeration tendency of CSRs has limited the improvement in the toughness of the epoxy adhesives, which can be resolved by the formation of proper chemical groups on their surface. The utilization of monomers possessing two distinct polymerization sites, such as divinyl benzene (DVB), is widely recognized for significantly enhancing grafting efficiency, gel content, and structural stability in CSR19. On the other hand, incorporation of fillers into the epoxy matrix can enhance the stiffness and thermal stability of the epoxy adhesive20,21,22. Zinc oxide nanoparticles can improve the stiffness, thermal stability, adhesion strength, and anti-corrosion properties of materials. They can also protect against UV light and make materials tougher23,24,25. Klinger et al.26 studied the influence of adding poly (methyl methacrylate-block-butyl acrylate-block-methyl methacrylate) and core–shell structures with poly butadiene core on the mechanical properties of epoxy. Their results indicated an increase in the toughness by the addition of both materials. Wang et al.27 assessed the effect of poly (methyl methacrylate-block-butyl acrylate-block-methyl methacrylate) and core–shell structure (with polybutadiene core and polymethyl methacrylate shell) on the mechanical and thermal properties of epoxy adhesive and showed the synergistic effect of the combination of these two toughening agents on the mechanical properties of epoxy adhesive as they increased the flexural strength and fracture toughness. Panta et al.28 employed a triblock copolymer and functionalized carbon nanotubes to enhance the adherence of epoxy adhesive, noting that the concurrent incorporation of these two materials had a synergistic effect on adhesive strength. Pang et al.29 demonstrated that manufacturing poly(ethylene-alt-propylene)-b-poly(ethylene oxide) and incorporating it into epoxy adhesive enhances both the adhesive strength and toughness of the epoxy adhesive. Kaveh et al.30 modified zirconia and silica nanoparticles with 3-Aminopropyltriethoxysilane (APTES) agent and added the modified nanoparticles to epoxy adhesives. Their results showed that the surface modification of nanoparticles improves the mechanical properties, adhesion strength, and thermal stability of epoxy adhesives. Also, the combination of zirconia and silica nanoparticles indicated a synergistic effect. Hajizamani et al.31 found that incorporating Ti3C2Tx nanoparticles into epoxy adhesives improves mechanical and thermal properties. Aung et al.32 blended the epoxy acrylate coating with nano zinc oxide to make hybrid nanocomposites as a corrosion protection coating applied to a mild steel panel. Incorporation of a 5 wt% zinc oxide loading showed significantly enhanced corrosion resistance through impedance spectroscopy as well as coating performance. Bershtein et al.33 developed three distinct sintered nanocomposites utilizing phthalonitrile and metal oxide particles: alumina, titanium dioxide, or zinc oxide. The introduction of zinc oxide nanoparticles boosted the UV-shielding characteristics of the neat matrix, as evidenced by the UV–visible transmittance spectra of the zinc oxide-containing nanocomposites. Nguyen et al.34 investigated the mechanical and thermal properties of nanocomposite coatings comprising epoxy, silica nanoparticles, iron oxide, titanium dioxide, zinc oxide, and clay. The TGA data indicate that zinc oxide exhibited the most pronounced impact on improving thermal stability relative to other nanoparticles. OzanKaya et al.35 examined the impact of incorporating graphene nanosheets and titanium dioxide on the shear strength of aluminum joints. Subsequently, they employed the ANN approach to model the experimental data.

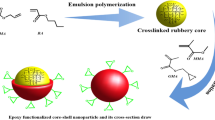

In this study DVB selected as the graft-linking monomer for the formulation of elastomeric cores in CSR particles. A redox emulsion copolymerization of methyl methacrylate (MMA) and glycidyl methacrylate (GMA) was conducted at the interface region between the elastomeric cores and the aqueous medium to fabricate the plastic shell. The implementation of a swelling period facilitated the dissolution of monomers within the poly (BA-DVB) gel particles, while radical generation processes at the interfacial area significantly reduced the probability of micellar and homogenous nucleation36. Furthermore, it is posited that this swelling duration promoted the grafting reaction between the elastomeric core and the glassy shell, hence augmenting the durability of the resultant shell during its amalgamation with epoxy polymer.

Additionally, zinc oxide nanoparticles were integrated for the first time into epoxy adhesive, accompanied by a CSR consisting of a poly(butyl acrylate-alkyl methacrylate) core and a poly(methyl methacrylate-glycidyl methacrylate) shell. The CSR can chemically bond with the 3D epoxy network owing to the presence of ether rings on its shell. Zinc oxide nanoparticles were used as reinforcement in epoxy adhesive because of their advantageous features. In addition, a two-step mixing process was used for better dispersion of particles in the epoxy matrix. For the first time, DOE and ANN approaches were employed to predict the mechanical properties of epoxy adhesives containing CSR particles and zinc oxide nanoparticles. In comparison to alternative modeling techniques, this method provides a straightforward model accessible to a diverse range of users. Modeling laboratory data can diminish the necessity for experiments. The combination of many models might yield more complete models. We anticipate that this research will offer an innovative method for forecasting the mechanical properties of epoxy-based adhesives.

Experimental

Materials

This study utilized epoxy prepolymer (EPON 828) as the adhesive matrix, with triethylene tetraamine (TETA) serving as the hardener, both obtained from Hexion Company in the USA. Xylene, utilized as a solvent for epoxy, was obtained from Merck in Germany. Sahand Petroplastic Company (Iran) supplied zinc oxide nanoparticles with an average size of 20–30 nm. Also, for the synthesis of CSR particles, monomers such as GMA, MMA, and DVB from Merck Chemical Co., as well as butyl acrylate (BA) from Fluka, were obtained and employed without further purification. Emulsogen ammonium persulphate (APS) 100 from Clariant, ter-butyl perbenzoate (TBPB) from Merck Chemical Co., sodium formaldehyde sulfoxylate (SFS), and APS from Aldrich were utilized.

Methods

Synthesis of CSR particles

CSR particles were manufactured via a two-stage emulsion polymerization method. Initially, elastomeric cores made of poly (BA-DVB) were synthesized using batch emulsion polymerization. To achieve this, 80 g of deionized water (DIW), 0.5 g of Emulsogen APS 100 (surfactant), 15 g of BA, and 0.08 g of DVB were pre-mixed and added to the reactor. It is well-known that employing a crosslinker in the core composition enhances the dimensional stability of the prepared CSR particles. Additionally, research has substantiated that using DVB improves the grafting efficiency of the shell through residual unsaturated bonds that are not involved in the polymerization during the core preparation stage41. The reactor’s contents were deoxygenated using nitrogen purging for 15 min to remove any dissolved oxygen that could inhibit the polymerization process. The temperature was subsequently elevated to 80 °C, and the polymerization reaction was initiated by adding 0.02 g of APS dissolved in 5 mL of deionized water. APS acts as a radical initiator for the polymerization process. The reaction mixture was allowed to polymerize, and samples were taken from the reactor at consistent intervals to monitor the conversion rate. Gravimetric examination of the samples indicated a final conversion of over 98% after 120 min.

During the second stage, copolymerization of MMA and GMA occurred on the surface of the synthesized elastomeric cores. To achieve this, 100 g of the produced latex (core particles), 4.5 g of MMA, 0.5 g of GMA, and 0.05 g of TBPB were introduced into the reactor and agitated for 30 min at ambient temperature. Subsequently, 5 mL of an aqueous solution comprising 0.05 g of SFS was introduced into the reactor to initiate the redox emulsion copolymerization. The redox emulsion copolymerization was conducted for 3 h at 30 °C, with a conversion rate of 98%. Employing such a redox polymerization system ensures high certainty for polymerization in the vicinity of the core surface and grafting of the employed monomers onto the surface of the particles. The produced latex was ultimately filtered through a 53 mm sieve, after which the filtrate was frozen for 12 h and subsequently freeze-dried for an additional 12 h to obtain the final CSR particles.

Preparation of adhesive samples

To make the samples, first 20 g of epoxy resin was poured into a suitable container, followed by adding 2 ml of xylene and mechanical mixing for 3 min at 200 rpm. Then, the specific amount of toughening agent (CSR particles) was added to the mixture, followed by 5 min of ultrasonication. In the next step, zinc oxide nanoparticles were added to the mixture (before adding, zinc oxide nanoparticles were placed in an oven for 2 h at 110 to dehumidify), followed by 5 min of ultrasonication. Subsequently, the mixture was stirred by a mechanical stirrer for 30 min at a certain speed to achieve better mixing. Then, the mixture was placed in a vacuum oven for one hour to remove the bubbles that may have entered the mixture during the mixing phase. Then 6.66 g of curing agent was added to the mixture and mechanically stirred for 10 min at 200 rpm (Fig. 1). Finally, dumbbell-shaped samples and aluminum-to-aluminum single-lap joints were prepared. For the final curing of the product, dumbbell-shaped samples were placed at ambient temperature for 7 days, while single-lap joints were cured for 2 days. The formulation designed to prepare the samples is shown in Table 1. Note that the samples are coded by C and Zn, standing for CSR particles and zinc oxide nanoparticles, respectively. The numbers also show the weight percentage of the materials.

Aluminum surface preparation

The anodizing process was performed to prepare metal surfaces for adhesive application. Aluminum foil was affixed to the positive terminal of the power supply as anodes. The secondary electrode was fabricated with platinum as the cathode and connected to the negative terminal of the power supply. The anodizing procedure involved immersing the electrodes in a 15% sulfuric acid solution and maintaining a steady voltage of 1.5 V for 5 min.

Characterization

FTIR test

The FT-IR spectrum was acquired utilizing a BRUKER-IFS 48 spectrophotometer (Germany) with a KBr pellet in the range of 4000–400 cm−1.

SEM test

The SEM study of the dimensions and surface morphology of the latex particles was performed utilizing the MIRA3 instrument from Tescan in the Czech Republic.

TEM test

The TEM technique employing the CEM 902A ZEISS system was utilized to analyze the internal structure and shell thickness of the latex particles, operating at an acceleration voltage of 80 keV at Oberkochen, Germany.

Tensile test

Adhesive specimens were evaluated for tensile qualities in accordance with ISO 527–1, 2, 3 testing standards. The tensile test was performed using the ASTM-400 tensile test machine (Santam Co., Iran) at a loading speed of 2 mm min−1, and an average value was documented following the testing of three to five specimens for each sample.

Lap shear strength test

The lap shear test was performed utilizing the ASTM D1002 metal specimens, measuring 0.8 mm in thickness, with a strain rate of 1.3 mm per minute. The samples were assessed utilizing STM-400 testing apparatus from Santam Co. Iran, at a loading rate of 1.3 mm min−1.

TGA test

The thermal stability of optimum adhesive samples was evaluated by a TGA test. TGA instrument (TGA1500, Metter Toledo Co., Switzerland) was performed from room temperature to 500 °C by the heating rate of 10 °C min−1 under a nitrogen atmosphere.

FESEM test

FESEM analysis was employed to examine the microstructure, dispersion of zinc oxide nanoparticles within the epoxy matrix substrate, and the fracture surface of the dumbbell samples exhibiting the highest tensile performance. Prior to analysis, the surfaces of the samples were coated with a thin layer of gold. FESEM images were obtained with the Tescan MIRA3 apparatus.

DSC test

DSC analysis was used to confirm the CSR structure and investigate its thermal properties. The heating rate of the DSC instrument (LABSIS Evo, SETARAM Inc., France) was adjusted to 10 °C min−1 from − 60 to 100 °C under nitrogen gas.

Results and discussion

FTIR test

Figure 2 illustrates the FTIR spectra of the synthesized CSR particles. The absorption maxima at 1730 cm−1 and 1160 cm−1 correspond to the C=O and C–O stretching vibrations of ester functional groups, respectively. The absorption maxima at 1230–1280 cm−1, 815–950 cm−1, and 750–770 cm−1 correspond to the symmetric stretching vibration and bending mode of the epoxy groups. These observations confirm that the GMA monomer effectively functionalized the CSR particles through epoxy rings37.

SEM and TEM test

The electron microscopy results for the synthesized CSR particles (shown in Fig. 3) show that particles with an average diameter of 346 µm were successfully made. TEM pictures indicate average core and shell dimensions of 283 nm and 45 nm, respectively. The diameter of the elastomeric core and the thickness of the glassy shell substantially influence the performance of CSR particles. Cutting down on particle size makes cavitation resistance better in elastomeric impact modifiers like CSR particles or carboxyl-terminated butadiene acrylonitrile (CTBN)38. Nevertheless, the efficacy of toughening diminishes for particle sizes smaller than 0.2 µm due to the difficulties associated with cavitation of the rubbery core39. Fracture toughness stays stable across wider particle size ranges40. Thus, the engineered elastomeric particles probably improve the toughness of epoxy resins through mechanisms such as induced plastic deformation and cavitation.

The principal role of the glassy shell in CSR particles is to establish a compatible interface between the elastomeric core and the epoxy matrix. This layer functions as a stress bridge, transmitting energy from the matrix to the rubbery core of CSR particles41. A reduced shell thickness promotes stress transfer from the polymer matrix to the rubbery core, thereby improving the performance of CSR particles. At the same time, a glassy shell that is thick enough ensures compatibility with the epoxy matrix and stops coalescence while the epoxy is drying and curing. The average shell thickness and fluidity of the synthesized CSR particles in their powdered state suggest a good range for dealing with these problems42.

DSC analysis

DSC analysis of CSR particles provides valuable insights into their thermal behavior and phase transitions. The obtained DSC thermogram revealed two primary thermal events. The first event, with a peak maximum at − 41.44 °C, is associated with the glass transition of the core portion of the CSR particles (shown in Fig. 4). This observation clearly indicates the formation of core particles in a distinct phase separate from the shell. The other thermal transitions, observed at 36.25 °C and 52.54 °C, are attributed to the polymer shell. Notably, the measured glass transition temperatures (Tg) of the shell are lower than the theoretical value expected for an MMA-GMA copolymer. This discrepancy is likely due to the thin thickness of the formed shell and the plasticizing effect of the core material43.

Overall, the DSC spectra, with their multiple transitions, confirm the successful formation of CSR particles. These transitions highlight the material’s ability to absorb and dissipate energy, a critical feature for its performance as an effective impact modifier44.

Tensile test

The modulus consistently diminished with the incorporation of CSR particles into epoxy (Fig. 5b), attributable to the presence of the softer component of the CSR particles. The rubber-like characteristics of the core, with a significantly lower modulus than epoxy, resulted in a reduction of the epoxy’s modulus upon the integration of the CSR particles45. The tensile strength and toughness increased with the incorporation of CSR particles up to 2.5 phr (Fig. 5a, c), likely due to the effective dispersion of the CSR particles and robust interaction between the CSR particles and epoxy. The carbonyl groups of methyl methacrylate can establish hydrogen bonds with the hydroxyl groups of the epoxy matrix, thereby strengthening their interface. The incorporation of ether rings in the CSR structure can augment the tensile strength, toughness, and fracture strain of epoxy. The sample with 2.5 phr CSR particles exhibited the highest tensile strength and toughness, measuring 33.7 MPa and 1395 kJ/m3, reflecting increases of 10% and 143%, respectively. The additional integration of CSR particles diminished the tensile strength and toughness, attributed to the agglomeration of these particles and a subsequent reduction in their interface with epoxy46.

Zinc oxide nanoparticles exhibit a significantly greater modulus than epoxy; hence, the incorporation of zinc oxide nanoparticles up to 2 phr increased the adhesive’s modulus to 2.94 GPa, reflecting a 37% enhancement relative to pure epoxy. Subsequently, the nanoparticles began to aggregate, creating space between the chains and facilitating their movement, which therefore led to a little decrease in modulus (Fig. 5b)47. Tensile strength and toughness demonstrated a similar pattern (Fig. 5a, c). The material containing 2 phr zinc oxide nanoparticles exhibit the best tensile strength and toughness, measuring 49 MPa and 1–45 kJ/m3, which represents improvements of 60% and 82% over pure epoxy, respectively. The appropriate dispersion of nanoparticles resulted in an increase in their content up to 2 phr, hence enhancing the contact area between the nanoparticles and epoxy. Increasing the nanoparticle load to 2 phr results in effective dispersion of nanoparticles within the epoxy matrix. Consequently, the interface and surface contact between zinc oxide nanoparticles and the epoxy matrix are enhanced. The augmentation of the interface between zinc oxide nanoparticles and epoxy results in an enhancement of hydrogen interactions between the nanoparticles and epoxy chains; the tensile strength of epoxy/zinc oxide nanoparticle adhesives is enhanced. An additional rise in nanoparticle concentration led to their aggregation, thereby diminishing their interaction with epoxy and resulting in a decline in mechanical characteristics48.

Regarding ternary samples, the tensile strength, tensile modulus, and toughness improved with the increase of nanoparticle and CSR particles content up to 2 and 2.5 phr, respectively; beyond these levels, the characteristics diminished due to agglomeration (Fig. 6a–c). In the optimum sample, comprising 2 phr zinc oxide nanoparticles and 2.5 phr CSR particles, the toughness exceeded that of the binary samples (1828 ± 28 kJ/m3), demonstrating a 218% increase relative to pure epoxy. The rationale for this lies in the synergistic function of the two additives, wherein the formation of hydrogen interactions between the zinc oxide nanoparticles and the CSR particles, in conjunction with the epoxy matrix, results in three-dimensional structural reinforcement and enhances the energy necessary for crack initiation and propagation49. The amalgamation of these two additives has established equilibrium in the mechanical property parameters, such as modulus, tensile strength, and fracture strain, hence enhancing toughness relative to binary samples. The tensile strength and tensile modulus of this sample are 46.1 ± 0.2 MPa and 2.79 ± 0.02 GPa, that exhibited improvements of 51% and 30%, respectively.

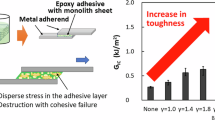

Lap shear strength test

The shear strength consistently increased with the elevation of CSR particles content (Fig. 5d). The shear strength attained 11.2 MPa in the sample containing 3.75 phr CSR particles, indicating a 30% increase relative to pure epoxy. The cause may be the efficient interaction of the CSR particles with the aluminum substrate, which improves the adhesive’s adherence to the substrate. The ether groups of the CSR particles can establish hydrogen bonds with the hydroxyl groups of the epoxy matrix and the oxidized surface of the aluminum substrate, which is generated by the anodizing process. Electrostatic interaction theory posits that the incorporation of CSR particles enhances the adhesive’s affinity for the substrate, hence augmenting shear strength50.

The incorporation of nanoparticles into the epoxy adhesive enhanced the adhesion among the adhesive components through interactions between the nanoparticles and epoxy groups while simultaneously improving the adhesive’s bond to the aluminum substrate by increasing interactions with its active surface (Fig. 5d). The hydrogen interactions of the adhesive with the substrate progressively intensified with an increase in nanoparticle content, resulting in enhanced shear strength51. Specifically, the shear strength of the sample containing 5 phr nanoparticles attained 12.6 MPa, reflecting a 47% enhancement relative to pure epoxy.

The augmentation of zinc oxide and CSR resulted in a rise in shear strength for the aforementioned reasons. The significant aspect of the ternary samples with single-lap joint specimens is the synergistic interaction between zinc oxide and the CSR structure. The maximum shear strength of epoxy/zinc oxide and epoxy/CSR samples was 12.6 MPa and 11.2 MPa, respectively, which increased to 19.5 ± 0.4 MPa in the ternary sample including epoxy, zinc oxide (5 phr), and CSR (3.75 phr), demonstrating a 127% enhancement relative to pure epoxy (Fig. 6d). The favorable interaction can be attributed to the hydrogen bonds formed between the hydroxyl groups of zinc oxide, the ether groups of the CSR surface, and the hydroxyl and ether groups of the epoxy matrix (Fig. 7a). Also, the theory of electrostatic interactions in adhesion posits that an increase in zinc oxide and CSR composition amplifies the hydrogen contacts between the adhesive and the oxidized aluminum substrate, resulting in a substantial increase in shear strength (Fig. 7b)52.

Figure 8 illustrates the fracture surface of single-lap joint pure epoxy specimens and the ultimate optimum sample. In the pure epoxy sample (Fig. 8a), the failure is adhesive in nature, resulting from the inadequate interaction between the adhesive and the substrate surface. Regarding the ultimate optimum sample (Fig. 8b), the adhesive’s adherence to the aluminum surface improved due to the effective interaction between the adhesive components and the anodized aluminum surface, resulting in a shift in the failure mode to cohesive53.

Table 2 compares the lap shear test results of our investigation with those from other recent publications. These articles employ DGEBA epoxy resin and TETA curing agent. The shear strength test was performed in accordance with the ASTM D1002 standard, utilizing aluminum substrates.

TGA test

Table 3 presents the initial degradation temperature, maximum degradation temperature, and residual char to assess the thermal stability of the samples.

The diglycidyl ether bisphenol A epoxy resin exhibits excellent thermal stability, characterized by a high crosslinking density network, with an initial degradation temperature of 177.5 °C, a maximum degradation temperature of 376 °C, and a residual char of 9.73% at 500 °C. The heat deterioration of epoxy resin occurs in three stages. The initial stage of deterioration occurring between 100–175 °C is attributed to the evaporation of moisture from the sample surfaces and the breakdown of low-molecular weight volatile constituents of the epoxy adhesive65. The primary weight loss transpired during the second stage within the temperature range of 175–375 °C, attributable to the degradation of the aromatic groups of bisphenol A, the cleavage of bonds with the amines of the curing agent, and the freedom of combustible gasses, amines, and gaseous aromatic compounds. The epoxy network was entirely destroyed at temperatures ranging from 375 to 500 °C66. Incorporating CSR particles up to 2.5 phr resulted in early deterioration and maximum degradation temperatures of 180 and 384 °C, respectively, reflecting increments of 2.5 and 8 °C compared to pure epoxy. The factors may include the association with the three-dimensional epoxy network, the appropriate interaction between the CSR and epoxy chains, and the effective dispersion of the CSR particles. Augmenting interactions elevates the energy requisite for their annihilation67. At a CSR particles composition of 3.75 phr, the dispersion of CSR particles deteriorated due to agglomeration, diminishing their contact with epoxy chains and consequently impairing the thermal characteristics. The integration of zinc oxide nanoparticles elevated both the initial and maximum degradation temperatures, while increasing the residual char. The enhanced thermal stability of zinc oxide -containing samples is due to the superior thermal stability and better thermal conductivity of zinc oxide nanoparticles compared to pure epoxy, which improves heat distribution in the nanocomposites and delays combustion68. The integration of zinc oxide nanoparticles into epoxy increased the energy necessary to disrupt the epoxy network due to the establishment of robust contacts with the epoxy matrix, hence enhancing the thermal characteristics. The initial degradation and maximum degradation temperatures were 204 and 426 °C in the sample containing 5 phr zinc oxide, indicating enhancements of 26.5 and 50 °C, respectively. The residual char consistently increased with the elevation of nanoparticle content, attributable to the heat resistance of zinc oxide nanoparticles in comparison to epoxy. The optimum ternary sample exhibited initial and maximum degradation temperatures of 192 and 397.5 °C, reflecting increments of 15 and 22 °C relative to pure epoxy, respectively. This sample exhibited a relationship among optimal binary samples. The weight loss is shown against temperature in Fig. 9.

FESEM test

Regarding similar amounts of resin, curing agents, and process conditions in all samples, the capacity of CSR particles to form chemical bonds with epoxy matrix is limited and almost constant. Therefore, a part of CSR particles is involved in chemical connections with the epoxy network, while the other part forms hydrogen bonds. Some of them also form agglomerates, whose probability increases by raising the content of CSR particles. Proper distribution can be seen up to CSR particles content of 2.5 phr (Fig. 10a, b), while evident agglomerations can be detected at CSR particles level of 3.75 phr (Fig. 10c).

The concentration of nanoparticles in the epoxy matrix rises with increased NP content; however, the samples containing 1 and 2 phr nanoparticles exhibited no discernible accumulation (Fig. 10d, e), whereas the sample with 5 phr demonstrated agglomeration (Fig. 10f), resulting in diminished mechanical properties.

To observe the fracture type and investigate the toughness mechanisms in the optimal samples, the fracture surfaces were imaged at higher magnifications in Fig. 11. The mentioned figure marks crack deflection, crack pinning, and debonding with red, yellow, and blue arrows, respectively.

Figure 11a illustrates that the flat fracture surface of the pure epoxy sample indicates a brittle fracture69. The fracture surface of the epoxy/CSR and epoxy/zinc oxide nanoparticles (Fig. 11b, c) is rough, indicating plastic deformation of the epoxy matrix. The coarser fracture surface indicates a rise in toughness energy, implying enhanced resistance of the nanocomposite to crack initiation and propagation70. The primary cause is crack deflection and its attenuation resulting from the presence of CSR structures or zinc oxide nanoparticles in the epoxy matrix. The dispersion of CSR particles within the epoxy resin might modify the strain rate71. The optimum ternary sample images exhibit rougher and wavier surfaces, signifying increased failure energy and toughness (Fig. 11d)72.

Modeling of mechanical properties

Employing DOE to forecast the physical characteristics of epoxy adhesive

Regression techniques are utilized to model the relationship between independent and dependent variables. Concurrently, linear regression methods have significant popularity. Occasionally, the linear regression model may be applied in scenarios with a nonlinear connection between the dependent and independent variables73. Polynomial regression characterizes the association with the dependent variable through a polynomial function of the independent variable74. A significant advantage of this strategy is its simplicity and practicality. This section models the mechanical properties (tensile strength, tensile modulus, toughness, and shear strength) of ternary samples (full factorial) as independent polynomials utilizing Minitab software. Table 4 presents the derived models together with their corresponding error values.

In these models, Zn and C coefficients indicate the main effect of zinc oxide and CSR, whereas Zn2 and C2 coefficients indicate the curvature of nanoparticles and CSR behavior. Zn*C coefficient also denotes the interaction between nanoparticles and CSR. For example, in the tensile strength model, the coefficient of Zn is greater than C, suggesting the higher effect of nanoparticles compared to the CSR in increasing the tensile strength. Moreover, Zn2 is larger than that of C2, indicating more nonlinear behavior of nanoparticles compared to CSR. Furthermore, the sign Zn2 and C2 indicates the direction of concavity. On the other hand, the values R2 and R2adj reveal the model error, the closer the value to 100, the smaller the model error. In these models, the R2 and R2adj values are greater than 95%, suggesting the low error of the models and the success of the modeling. It was tried to simplify the models as much as possible by omitting unnecessary terms (to the extent that R2adj does not fall below 95%), therefore, Zn*C parameters were eliminated due to the small interaction of nanoparticles and CSR in derive models related to tensile strength, tensile modulus, and toughness. Concerning the tensile modulus model, the C2 parameter was omitted considering the linear assumption of the CSR effect. Regarding the smaller range of tensile strength and tensile modulus compared to toughness and shear strength, the R2 value of their model is also larger (lower error). Furthermore, the difference of R2 and R2adj values in shear strength model is more due to less repetition of shear strength test samples compared to tensile test. Using the models in Table 4, the mechanical properties of epoxy adhesives containing zinc oxide nanoparticles and CSR particles can be predicted with a low error percentage.

Employing ANN to forecast the physical characteristics of epoxy adhesive

This study employed a feed-forward MLP network to predict the mechanical properties of epoxy adhesives like tensile strength, tensile modulus, toughness, and shear strength. The MLP network comprises four layers: an input layer, two hidden layers, and an output layer. The input layer comprises a pair of neurons (zinc oxide and CSR). Figure 12 presents a schematic depiction of the constructed ANN.

Sixteen experimental data sets are divided into three segments: training data, validation data, and test data. Seventy percent of all data is randomly selected for training the network, fifteen percent for verifying the network, and the remaining proportion for testing the network. The neural network toolbox in the MATLAB programming environment facilitates the creation of the MLP network. The trainlm function, integral to the Levenberg–Marquardt training algorithm, is utilized for training the MLP network75. Table 5 presents the required bias and weight values for the proposed MLP network aimed at forecasting mechanical properties.

An insufficient number of neurons in the hidden layer impedes the network’s training process and leads to suboptimal performance. Conversely, an excessive number of neurons in the hidden layer may lead to overfitting of the training data76,77. The trained neural network’s Mean Squared Error (MSE) and Mean Relative Error (MRE) were calculated for different hidden layer neuron numbers (6–12). The ideal network architecture was chosen based on minimizing MSE and MRE, excluding redundant calculations from Table 6. Table 6 illustrates that the optimal ANN configuration for forecasting parameters of the output layer comprises a four-layer network featuring two neurons in the input layer, eight neurons in each of the first and second hidden layers, and four neurons in the output layer (see Fig. 12). The reliability and validity of the predicted ANN for parameters of the output layer were evaluated by juxtaposing the ANN results with experimental training, validation, and test datasets, as seen in Fig. 13a–c. The solid line denotes the optimal correspondence. The proposed ANN has a strong correlation with experimental data, with R2 statistics of 0.9998, 0.9771, and 0.8705 for network predictions across training, validation, and test datasets.

Table 7 shows the MSE and MRE of trained ANNs in forecasting tensile strength, tensile modulus, toughness, and lap shear strength. ANNs struggle to apply their skills to novel scenarios and rely on the quality and quantity of training data. To improve feed-forward MLP networks for precise prediction of epoxy adhesives, supplementary experimental data is recommended.

Conclusion

Experimental outcomes

In this study, a CSR structure comprising a poly(butyl acrylate-alkyl methacrylate) core and a poly(methyl methacrylate-glycidyl methacrylate) shell was utilized as a toughening agent, while zinc oxide nanoparticles used as a reinforcing agent in the formulation of epoxy adhesives. For better dispersion of zinc oxide nanoparticles and CSR particles, a two-step mixing process was used. Samples of the aluminum-to-aluminum single-lap junction in a dumbbell shape were also fabricated. The principal outcomes are enumerated as follows:

-

The results of FTIR, SEM, TEM and DSC analyses validated the successful synthesis of CSR particles.

-

The tensile test results demonstrated the greatest boost in tensile strength and modulus in the sample containing 2 phr zinc oxide nanoparticles, achieving 49 MPa and 2.94 GPa, reflecting improvements of 60% and 37%, respectively.

-

The maximum in the toughness of the epoxy specimen with 2.5 phr CSR particles and 2 phr zinc oxide nanoparticles was 1828 kJm−3.

-

The lap shear test indicated that the epoxy sample containing 3.75 phr CSR particles and 5 phr zinc oxide nanoparticles had the greatest increase in shear strength, measuring 19.5 MPa, which represents a 127% improvement over pure epoxy. This sample demonstrated a notable synergistic impact among the components.

-

The TGA results indicated that the specimen with 5 phr zinc oxide nanoparticles exhibited the strongest thermal stability, with initial degradation and maximum degradation temperatures increasing by 26.5 and 50 °C, respectively, compared to pure epoxy.

-

The analysis of the fracture surface using FESEM corresponded with the mechanical properties results. The primary toughness mechanisms of the sample comprising zinc oxide nanoparticles and a CSR structure included fracture deflection, crack pinning, and particle debonding.

Modeling outcomes

The tensile strength, tensile modulus, toughness, and shear strength were modeled using DOE and ANN approaches.

-

The DOE results comprised four distinct polynomials that exhibited a strong correlation with the experimental data, demonstrating minimal error (R2 adj > 95%).

-

The ANN results were presented in an integrated format and shown a strong correlation with the experimental data (MREave < 3.2).

Data availability

The data presented in this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Liu, Y. et al. Study on the synthetic mechanism of monodispersed polystyrene-nickel composite microspheres and its application in facile synthesis of epoxy resin-based anisotropic conductive adhesives. Colloids Surfaces A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 656, 130378. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colsurfa.2022.130378 (2023).

Aliakbari, M., Jazani, O. M., Sohrabian, M., Jouyandeh, M. & Saeb, M. R. Multi-nationality epoxy adhesives on trial for future nanocomposite developments. Prog. Org. Coatings 133, 376–386 (2019).

Xu, W., Yang, C., Su, W., Zhong, N. & Xia, X. Effective corrosion protection by PDA-BN@CeO2 nanocomposite epoxy coatings. Colloids Surfaces A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 657, 130448 (2023).

Rahman, T. et al. Synergistic effect of positive temperature coefficient and thermally conductive micro-nano fillers on electrical and thermal properties of epoxy resin. Polym. Compos. 45, 8590–8600 (2024).

Xu, N. et al. A mussel-inspired strategy for CNT/carbon fiber reinforced epoxy composite by hierarchical surface modification. Colloids Surfaces A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 635, 128085 (2022).

Ahmadi, Z. Nanostructured epoxy adhesives: A review. Prog. Org. Coatings 135, 449–453 (2019).

Jouyandeh, M. et al. Highly curable self-healing vitrimer-like cellulose-modified halloysite nanotube/epoxy nanocomposite coatings. Chem. Eng. J. 396, 125196 (2020).

Gholinezhad, F., Golhosseini, R. & Moini Jazani, O. Synthesis, characterization, and properties of silicone grafted epoxy/acrylonitrile butadiene styrene/graphene oxide nanocomposite with high adhesion strength and thermal stability. Polym. Compos. 43, 1665–1684 (2022).

Jouyandeh, M. et al. Curing behavior of epoxy/Fe 3 O 4 nanocomposites: A comparison between the effects of bare Fe 3 O 4, Fe 3 O 4 /SiO 2 /chitosan and Fe 3 O 4 /SiO 2 /chitosan/imide/phenylalanine-modified nanofillers. Prog. Org. Coatings 123, 10–19 (2018).

Jouyandeh, M. et al. Curing epoxy resin with anhydride in the presence of halloysite nanotubes: The contradictory effects of filler concentration. Prog. Org. Coatings 126, 129–135 (2019).

Liu, N. et al. Enhancing cryogenic mechanical properties of epoxy resins toughened by biscitraconimide resin. Compos. Sci. Technol. 220, 109252 (2022).

Zhang, J., de Souza, M., Creighton, C. & Varley, R. J. New approaches to bonding thermoplastic and thermoset polymer composites. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 133, 105870 (2020).

Kowsar, M. J., Moini Jazani, O., Dini, G. & Moghadam, M. A novel epoxy adhesive with metal organic framework (MOF) and poly(butyl acrylate-block-styrene) for bonding aluminum–aluminum joints: A complete overview of mechanical, thermal, and morphological properties. Polym. Adv. Technol. 35, e6259 (2024).

Neves, R. M., Ornaghi, H. L., Zattera, A. J. & Amico, S. C. Toughening epoxy resin with liquid rubber and its hybrid composites: A systematic review. J. Polym. Res. 29, 1–15 (2022).

Aliakbari, M., Jazani, O. M. & Sohrabian, M. Epoxy adhesives toughened with waste tire powder, nanoclay, and phenolic resin for metal-polymer lap-joint applications. Prog. Org. Coatings 136, 105291 (2019).

Xia, L. et al. Cu2O based on core-shell nanostructure for enhancing the fire-resistance, antibacterial properties and mechanical properties of epoxy resin. Compos. Commun. 37, 101445 (2023).

Wu, Q. et al. Core-shell ZrO2@GO hybrid for effective interfacial adhesion improvement of carbon fiber/epoxy composites. Surfaces Interfaces 40, 103070 (2023).

Wang, Z. et al. Novel phosphorus-free and core–shell structured ZIF-67 for simultaneously endowing epoxy resin with excellent fire safety, corrosion and UV resistance. Eur. Polym. J. 194, 112159 (2023).

Bouvier-Fontes, L., Pirri, R., Asua, J. M. & Leiza, J. R. Cross-linking emulsion copolymerization of butyl acrylate with diallyl maleate. J. Polym. Sci. Part A Polym. Chem. 43, 4684–4694 (2005).

Deyab, M. A., Alghamdi, M. M., El-Zahhar, A. A. & El-Shamy, O. A. A. Advantages of CoS2 nano-particles on the corrosion resistance and adhesiveness of epoxy coatings. Sci. Rep. 14, 1–8 (2024).

Tee, Z. Y., Yeap, S. P., Hassan, C. S. & Kiew, P. L. Nano and non-nano fillers in enhancing mechanical properties of epoxy resins: A brief review. Polym. Technol. Mater. 61, 709–725 (2022).

Farzanehfar, N., Taheri, A., Rafiemanzelat, F. & Jazani, O. M. High-performance epoxy nanocomposite adhesives with enhanced mechanical, thermal and adhesion properties based on new nanoscale ionic materials. Chem. Eng. J. 471, 144428 (2023).

Jiang, Z. et al. Research progresses in preparation methods and applications of zinc oxide nanoparticles. J. Alloys Compd. 956, 170316 (2023).

Zhou, X. Q. et al. Zinc oxide nanoparticles: Synthesis, characterization, modification, and applications in food and agriculture. Process 11, 1193 (2023).

Mirmohammadi, S. M., Moini Jazani, O., Ahangaran, F. & Khademi, M. H. Thermomechanical behavior of a novel hybrid epoxy/ZnO nanocomposite adhesive in structural bonding: Experimental analysis and ANN modeling. Colloids Surfaces A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 687, 133495 (2024).

Klingler, A., Bajpai, A. & Wetzel, B. The effect of block copolymer and core-shell rubber hybrid toughening on morphology and fracture of epoxy-based fibre reinforced composites. Eng. Fract. Mech. 203, 81–101 (2018).

Wang, J. et al. Synergistically effects of copolymer and core-shell particles for toughening epoxy. Polymer (Guildf). 140, 39–46 (2018).

Panta, J. et al. Influence of amino-functionalized carbon nanotubes and acrylic triblock copolymer on lap shear and butt joint strength of high viscosity epoxy at room and elevated temperatures. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 134, 103770 (2024).

Pang, V., Thompson, Z. J., Joly, G. D., Bates, F. S. & Francis, L. F. Adhesion strength of block copolymer toughened epoxy on aluminum. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2, 464–474 (2020).

Kaveh, A. et al. Introducing a new approach for designing advanced epoxy film adhesives with high mechanical, adhesion, and thermal properties by adding hybrid additives for structural bonding. Colloids Surfaces A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 676, 132180 (2023).

Hajizamani, E., Moini Jazani, O. & Riazi, H. Design and characterization of a novel supported epoxy film adhesive reinforced by Ti3C2Tx MXene nanoparticles. Mater. Chem. Phys. 308, 128270 (2023).

Aung, M. M., Li, W. J. & Lim, H. N. Improvement of anticorrosion coating properties in bio-based polymer epoxy acrylate incorporated with nano zinc oxide particles. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 59, 1753–1763 (2020).

Bershtein, V. A. & Yakushev, P. N. Phthalonitrile/metal oxide nanocomposites. Springer Ser. Mater. Sci. 334, 135–145 (2023).

Nguyen, T. A., Nguyen, H., Nguyen, T. V., Thai, H. & Shi, X. Effect of nanoparticles on the thermal and mechanical properties of epoxy coatings. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 16, 9874–9881 (2016).

Ozankaya, G. et al. Prediction of lap shear strength of GNP and TiO2/epoxy nanocomposite adhesives. Nanotechnol. Rev. https://doi.org/10.1515/ntrev-2023-0134 (2023).

Gharieh, A., Mahdavian, A. R. & Salehi-Mobarakeh, H. Preparation of core-shell impact modifier particles for PVC with nanometric shell thickness through seeded emulsion polymerization. Iran. Polym. J. English Ed. 23, 27–35 (2014).

Rahim-Abadi, M. M., Mahdavian, A. R., Gharieh, A. & Salehi-Mobarakeh, H. Chemical modification of TiO2 nanoparticles as an effective way for encapsulation in polyacrylic shell via emulsion polymerization. Prog. Org. Coatings 88, 310–315 (2015).

Guild, F. J., Kinloch, A. J. & Taylor, A. C. Particle cavitation in rubber toughened epoxies: The role of particle size. J. Mater. Sci. 45, 3882–3894 (2010).

Kim, D. S., Cho, K., Kim, J. K. & Park, C. E. Effects of particle size and rubber content on fracture toughness in rubber-modified epoxies. Polym. Eng. Sci. 36, 755–768 (1996).

Bajpai, A., Wetzel, B., Klingler, A. & Friedrich, K. Mechanical properties and fracture behavior of high-performance epoxy nanocomposites modified with block polymer and core–shell rubber particles. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 137, 48471 (2020).

Gharieh, A., Moghadas, M. & Pourghasem, M. Synergistic effects of acrylic/silica armored structured nanoparticles on the toughness and physicomechanical properties of epoxy polymers. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 3, 4008–4016 (2021).

Wu, G., Zhao, J., Shi, H. & Zhang, H. The influence of core–shell structured modifiers on the toughness of poly (vinyl chloride). Eur. Polym. J. 40, 2451–2456 (2004).

Nguyen, H. K., Labardi, M., Lucchesi, M., Rolla, P. & Prevosto, D. Plasticization in ultrathin polymer films: The role of supporting substrate and annealing. Macromolecules 46, 555–561 (2013).

Smith, M. J. & Verbeek, C. J. R. Energy absorption mechanisms and impact strength modification in multiphase biopolymer systems. Recent Patents Mater. Sci. 11, 2–18 (2018).

Fallahi, M., Moini Jazani, O. & Molla-Abbasi, P. Design and characterization of high-performance epoxy adhesive with block copolymer and alumina nanoparticles in aluminum-aluminum bonded joints: Mechanical properties, lap shear strength, and thermal stability. Polym. Compos. 43, 1637–1655 (2022).

Mousavi, S. R. et al. Toughening of epoxy resin systems using core–shell rubber particles: a literature review. J. Mater. Sci. 56, 18345–18367 (2021).

Nayak, R. K., Dash, A. & Ray, B. C. Effect of epoxy modifiers (Al2O3/SiO2/TiO2) on mechanical performance of epoxy/glass fiber hybrid composites. Procedia Mater. Sci. 6, 1359–1364 (2014).

Baghdadi, Y. N. et al. The effects of modified zinc oxide nanoparticles on the mechanical/thermal properties of epoxy resin. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 137, 49330 (2020).

Awais, M. et al. Synergistic effects of Micro-hBN and core-shell Nano-TiO2@SiO2 on thermal and electrical properties of epoxy at high frequencies and temperatures. Compos. Sci. Technol. 227, 109576 (2022).

Quan, D., Carolan, D., Rouge, C., Murphy, N. & Ivankovic, A. Carbon nanotubes and core–shell rubber nanoparticles modified structural epoxy adhesives. J. Mater. Sci. 52, 4493–4508 (2017).

Karthikeyan, L. et al. Zinc oxide tetrapod-based thermally conducting epoxy systems for aerospace applications. Trans. Indian Natl. Acad. Eng. 6, 71–77 (2020).

Han, S. et al. Synergistic effect of graphene and carbon nanotube on lap shear strength and electrical conductivity of epoxy adhesives. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 136, 48056 (2019).

Chu, C. W., Zhang, Y., Obayashi, K., Kojio, K. & Takahara, A. Single-lap joints bonded with epoxy nanocomposite adhesives: Effect of organoclay reinforcement on adhesion and fatigue behaviors. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 3, 3428–3437 (2021).

Kumar, R. et al. Epoxy-based composite adhesives: Effect of hybrid fillers on thermal conductivity, rheology, and lap shear strength. Polym. Adv. Technol. 30, 1365–1374 (2019).

Kumar, R. et al. Study on thermal conductive epoxy adhesive based on adopting hexagonal boron nitride/graphite hybrids. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 29, 16932–16938 (2018).

Aradhana, R., Mohanty, S. & Nayak, S. K. High performance electrically conductive epoxy/reduced graphene oxide adhesives for electronics packaging applications. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 30, 4296–4309 (2019).

Aradhana, R., Mohanty, S. & Nayak, S. K. Comparison of mechanical, electrical and thermal properties in graphene oxide and reduced graphene oxide filled epoxy nanocomposite adhesives. Polymer (Guildf). 141, 109–123 (2018).

Aradhana, R., Mohanty, S. & Nayak, S. K. Synergistic effect of polypyrrole and reduced graphene oxide on mechanical, electrical and thermal properties of epoxy adhesives. Polymer (Guildf). 166, 215–228 (2019).

Baby, M., Periya, V. K., Sankaranarayanan, S. K. & Maniyeri, S. C. Bioinspired surface activators for wet/dry environments through greener epoxy-catechol amine chemistry. Appl. Surf. Sci. 505, 144414 (2020).

Nayak, S. K., Mohanty, S. & Nayak, S. K. Decomposed Copper(II) acetate over expanded graphite (EG) as hybrid filler to fabricate epoxy based thermal interface materials (TIMs). J. Electron. Mater. 49, 34–47 (2020).

Nayak, S. K., Mohanty, S. & Nayak, S. K. Thermal, electrical and mechanical properties of expanded graphite and micro-SiC filled hybrid epoxy composite for electronic packaging applications. J. Electron. Mater. 49, 212–225 (2020).

Karthikeyan, L., Robert, T. M., Mathew, D., Desakumaran Suma, D. & Thomas, D. Novel epoxy resin adhesives toughened by functionalized poly (ether ether ketone) s. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 106, 102816 (2021).

Karthikeyan, L., Robert, T. M., Desakumaran, D., Balachandran, N. & Mathew, D. Epoxy terminated, urethane-bridged poly (ether ether ketone) as a reactive toughening agent for epoxy resins. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 112, 102983 (2022).

Khan, N. I., Halder, S. & Goyat, M. S. Influence of dual-component microcapsules on self-healing efficiency and performance of metal-epoxy composite-lap joints. J. Adhes. 93, 949–963 (2017).

Nikkhah Varkani, M., Moini Jazani, O., Sohrabian, M., Torabpour Esfahani, A. & Fallahi, M. Design, preparation and characterization of a high-performance epoxy adhesive with poly (butylacrylate-block-styrene) block copolymer and zirconia nano particles in aluminum- aluminum bonded joints. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym. Mater. 33, 3595–3616 (2023).

Karami, Z. et al. Epoxy/layered double hydroxide (LDH) nanocomposites: Synthesis, characterization, and Excellent cure feature of nitrate anion intercalated Zn-Al LDH. Prog. Org. Coatings 136, 105218 (2019).

Zotti, A., Zuppolini, S., Borriello, A. & Zarrelli, M. Thermal properties and fracture toughness of epoxy nanocomposites loaded with hyperbranched-polymers-based core/shell nanoparticles. Nanomater 9, 418 (2019).

Salahuddin, N. A., El-Kemary, M. & Ibrahim, E. M. High-performance flexible epoxy/ZnO nanocomposites with enhanced mechanical and thermal properties. Polym. Eng. Sci. 57, 932–946 (2017).

Karami, Z. et al. Well-cured silicone/halloysite nanotubes nanocomposite coatings. Prog. Org. Coatings 129, 357–365 (2019).

Jouyandeh, M., Moini Jazani, O., Navarchian, A. H. & Saeb, M. R. High-performance epoxy-based adhesives reinforced with alumina and silica for carbon fiber composite/steel bonded joints. J. Reinforced Plastics Compos. 35(23), 1685–1695. https://doi.org/10.1177/0731684416665248 (2016).

Jouyandeh, M. et al. Bushy-surface hybrid nanoparticles for developing epoxy superadhesives. Appl. Surface Sci. 479, 1148–1160 (2019).

Jouyandeh, M. et al. Surface engineering of nanoparticles with macromolecules for epoxy curing: Development of super-reactive nitrogen-rich nanosilica through surface chemistry manipulation. Appl. Surf. Sci. 447, 152–164 (2018).

Regression Analysis and Linear Models: Concepts, Applications, and ... - Richard B. Darlington, Andrew F. Hayes - Google Books. https://books.google.com/books?hl=fa&lr=&id=YDgoDAAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PP1&dq=Darlington,+R.+B.,+%26+Hayes,+A.+F.+(2016).+Regression+analysis+and+linear+models:+Concepts,+applications,+and+implementation.+Guilford+Publications.&ots=8iHYzMlBBy&sig=Q0KYYX5xqxJvoSu-cxIiWt1qJN4#v=onepage&q&f=false.

Dalal, D. K. & Zickar, M. J. Some common myths about centering predictor variables in moderated multiple regression and polynomial regression. Organiz. Res. Methods 15(3), 339–362. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428111430540 (2011).

Yu, H. & Wilamowski, B. M. Levenberg-marquardt training. Intell. Syst. https://doi.org/10.1201/9781315218427-12/LEVENBERG (2016).

Eslamloueyan, R. & Khademi, M. H. Using artificial neural networks for estimation of thermal conductivity of binary gaseous mixtures. J. Chem. Eng. Data 54, 922–932 (2009).

Eslamloueyan, R., Khademi, M. H. & Mazinani, S. Using a multilayer perceptron network for thermal conductivity prediction of aqueous electrolyte solutions. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 50, 4050–4056 (2011).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Omid Moini Jazani: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing—Review & Editing Seyyed Mohammad Mirmohammadi.: Writing—Original Draft, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Visualization Ali Gharieh: Formal Analysis, Validation, Writing—Review & Editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mirmohammadi, S.M., Moini Jazani, O. & Gharieh, A. Thermomechanical analyses and ANN modeling of novel epoxy adhesives with CSR particles and zinc oxide nanoparticles in structural bonding. Sci Rep 15, 11201 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96270-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96270-6