Abstract

In view of the phenomenon of ultra-large drilling cuttings quantity in rockburst coal seams, the concept of ultra-large drilling cuttings quantity has been proposed. A plastic damage strain sof-tening mechanical analysis model for coal seam drilling cuttings hole has been established. Us-ing the disturbance-induced instability theory, we investigate the mechanism of the ultra-large drilling cuttings quantity in coal and derive an analytical solution for its triggering conditions. The main influencing factors of the ultra-large drilling cuttings quantity phenomenon and its relationship with rockburst have been analyzed. The research results show that: the phenome-non of ultra-large drilling cuttings quantity occurs under various conditions, such as different mine depth and different strength of coal bodies, and is the result of disturbance and instability of the drilling cuttings hole structure, which is different from gravity-induced collapse and gas or stress-induced blowout. The initiation conditions for the ultra-large drilling cuttings quantity phenomenon in coal are mainly controlled by the bursting energy index KE and compressive strength σc. The larger the bursting energy index KE , the smaller the critical stress for the initia-tion of the ultra-large drilling cuttings quantity phenomenon, making it more likely to occur, conversely, the larger the compressive strength σc, the larger the critical stress required for the initiation of the ultra-large drilling cuttings quantity phenomenon, making it less likely to oc-cur. The bulk density of the coal only affects the critical value of the ultra-large drilling cuttings quantity and does not change the critical stress for the initiation of the phenomenon. The ul-tra-large drilling cuttings quantity in coal is sudden and locally destructive, more likely to occur in brittle coal or soft coal but can be more severe in hard coal. The initiation conditions for ul-tra-large drilling cuttings quantity in coal share the same controlling factors and patterns of change as the occurrence conditions for rockburst. When the ultra-large drilling cuttings quan-tity phenomenon appears in a borehole, the stress in the surrounding rock of the roadway has reached the critical stress level necessary for a rockburst to occur. This indicates that the ul-tra-large drilling cuttings quantity phenomenon can serve as a dynamic phenomenon to assess the burst risk of the roadway.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Rockburst is a dynamic phenomenon in which the unstable surrounding rock structure of underground roadways suddenly releases elastic deformation energy under external disturbances, leading to instability1,2,3,4. Characterized by high destructive intensity, rockbursts can cause damage ranging from several meters to hundreds of meters, posing significant challenges to the safe and efficient mining of many coal mines. As a result, rockburst has become a prominent research topic in the coal industry5,6,7. In rockburst monitoring, the drilling cuttings method is a widely used local monitoring and prediction technique. By analyzing variations in drilling cuttings quantity per unit depth and dynamic phenomena during drilling, the risk of rockburst can be assessed, enabling the prediction of rockburst events8,9,10,11,12. Typically, the drilling cuttings quantity is limited, with normal values generally not exceeding 6 kg/m13,14. However, with increasing mining depth and intensity, the actual drilling cuttings quantity in the field can far exceed normal levels, with drilling cuttings multiples reaching tens or even thousands, resulting in ultra-large drilling cuttings quantities of over one ton per meter. Intuitively, the phenomenon of ultra-large drilling cuttings quantity reflects the abnormal stress state of the coal and the instability of the drilling hole structure. What, then, is the specific mechanism behind the occurrence of ultra-large drilling cuttings quantity? Can it be used to assess the rockburst risk of roadways, i.e., what is the relationship between the ultra-large drilling cuttings quantity phenomenon and rockburst risk? It is necessary to investigate this phenomenon, especially as deep mining becomes more prevalent, where complex mining environments may make the ultra-large drilling cuttings quantity phenomenon more pronounced.

The key to studying the drilling cuttings method lies in establishing a more accurate relationship between the drilling cuttings quantity and coal stress. Many scholars have conducted in-depth research on this topic and achieved significant results. Pan Yishan15 established an elastic-plastic softening and dilatation model for coal, deriving an analytical expression for the drilling cuttings quantity. Wen Guangcai et al.16 developed a drilling cuttings quantity analysis model for gas-bearing coal seams, obtaining the relationship between drilling cuttings quantity around the borehole and factors such as borehole diameter, in-situ stress, coal strength, and gas pressure through numerical calculations. Cui Naixin17 considered the influence of gas on coal seams and micro-damage, deriving a formula for drilling cuttings quantity per unit depth in gas-bearing coal seams. Li Zhonghua18 proposed a drilling cuttings risk index formula for predicting rockburst in high-gas coal seams. Yin Guangzhi19 combined theories of longwall mining pressure and gas pressure distribution to analyze the relationship between drilling cuttings quantity, mining pressure, and gas pressure. Qu Xiaocheng20 conducted field tests and numerical simulations to establish the correspondence between borehole surrounding rock stress and drilling cuttings quantity. Yin Yongming et al.21 derived coal stress from the drilling cuttings quantity formula and established an evaluation index for drilling cuttings quantity. Tang Jupeng et al.22,23 introduced effective stress to account for horizontal in-situ stress in deep mining, resulting in a new drilling cuttings quantity formula. Recent theoretical research on drilling cuttings quantity has primarily focused on establishing relationships between drilling cuttings quantity and coal stress for conventional drilling cuttings quantities, with little attention paid to the phenomenon of ultra-large drilling cuttings quantity.

In fact, Cook24 discussed the phenomenon of ultra-large drilling cuttings quantity as early as the 1960s, providing a simple explanation for its occurrence conditions but without a clear definition or detailed analysis. This paper first defines the ultra-large drilling cuttings quantity phenomenon based on field observations. Building on previous theoretical research, a plastic strain softening model for coal seam drilling holes considering damage is established. Using the disturbance response instability theory, the initiation conditions, main influencing factors, and relationship with rockburst are explored, revealing the mechanism behind the ultra-large drilling cuttings quantity phenomenon and its role in rockburst monitoring.

Definition of ultra-large drilling cuttings quantity in coal seams

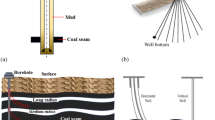

Drilling cuttings method

The drilling cuttings method is a localized prediction technique for rockburst that simultaneously detects multiple factors related to rockburst25,26. It involves using handheld electric drills or pneumatic drills with 1.0 m extension drill rods and typically a Φ42 mm drill bit to construct drilling holes perpendicular to the coal wall, extending beyond the peak stress zone of the coal wall, as shown in Fig. 1. The drilling cuttings quantity per meter of drilling depth is measured using either the weight method or the volume method. The weight method measures the weight of cuttings per meter (unit: kg/m), while the volume method measures the volume of cuttings per meter (unit: L/m). The measured drilling cuttings data are compared with standard indicators to assess rockburst risk. Additionally, dynamic phenomena such as drill jamming, noises, and blowouts during drilling are used to evaluate the risk of rockburst.

Drilling cuttings quantity

The drilling cuttings quantity consists of two parts: one is the volume of coal within the drill hole diameter that is not subjected to stress, and the other is the volume of coal generated due to deformation under stress. In rockburst monitoring and early warning, the normal drilling cuttings quantity refers to the quantity measured in areas unaffected by mining activities or geological structures. Typically, the normal drilling cuttings quantity is small, generally not exceeding 6 kg/m.

Ultra-large drilling cuttings quantity

Based on field statistics, this paper defines the phenomenon of ultra-large drilling cuttings quantity as occurring when the actual drilling cuttings quantity is ten times or more than the normal value. Although research on this phenomenon is limited, it is not uncommon in coal mining sites. Literature and field investigations have revealed that this phenomenon has occurred in several coal mines, such as Zhangshuanglou Coal Mine, Pingmei No. 8 Mine, Pingmei No.12 Mine, Hegang Xingshan Mine, a mine in Kailuan, and a mine in Tuokexun, Xinjian.

Case study: ultra-large drilling cuttings quantity in Zhangshuanglou coal mine

Detailed records of the ultra-large drilling cuttings quantity phenomenon are scarce, partly because it has not yet garnered sufficient attention from field personnel and researchers. Often, this phenomenon is simply attributed to excessive drilling cuttings caused by high stress or hole collapse. Below, the ultra-large drilling cuttings quantity phenomenon in Zhangshuanglou Coal Mine is analyzed as a case study.

Overview of Zhangshuanglou coal mine

Zhangshuanglou Coal Mine, operated by Xuzhou Mining Group, has a long mining history and complex production conditions. The main coal seams mined are the No. 7 and No. 9 seams, which have been identified as having a strong propensity for rockburst. The mine has experienced multiple rockburst incidents, including a significant event on July 30, 2010, at 3:15 AM, in the − 1200 m east mining area, which resulted in 6 fatalities, multiple injuries, and substantial economic losses. The 7123 working face, located only 80 m vertically from the site of the “7.30” incident, exhibited the ultra-large drilling cuttings quantity phenomenon multiple times during mining.

Drilling hole layout at the 7123 working face

The 7123 working face is located in the east mining area and features a monocline structure with a dip angle of approximately 22°. The mining depth ranges from 931.7 m to 961.7 m, with a coal seam thickness of 4.05 m. The immediate roof consists of 8 m of mudstone or sandy mudstone, while the main roof is 3.25 m of medium-fine sandstone. The immediate floor is 3.48 m of gray-black mudstone, and the main floor is 26.62 m of fine sandstone. Drilling measurement points were arranged along the mining side of the 7123 working face material roadway. Within a 90 m advance range of the working face, drilling holes were spaced every 15 m, with a drill bit diameter of 42 mm and a hole depth of 10 m, drilled perpendicular to the roadway side.

Ultra-large drilling cuttings quantity phenomenon

The 7123 working face material roadway recorded 42 instances of drilling cuttings quantities exceeding normal values within an 80 m advance range. These occurrences were mostly observed at depths of 6 ~ 10 m. Typically, the drilling cuttings quantity was normal for the first 7 m, but at the 8 m mark, the quantity suddenly increased dramatically, accompanied by large coal particles, noises, vibrations, and other dynamic phenomena. Beyond 10 m, the drilling cuttings quantity returned to normal.

Drilling holes 16#, 17#, 18#, 20#, and 21# were drilled sequentially along the upper side of the 7123 working face material roadway, starting 1350 m from the open-off cut. During drilling, the drilling cuttings quantity exceeded normal values multiple times, as shown in Fig. 2. From Fig. 2, it can be seen that the drilling cuttings quantities for holes 16#, 17#, 18#, 20#, and 21# at depths of 8 ~ 10 m were more than 10 times the normal value. Notably, the drilling cuttings quantity for hole 17# reached 180 kg, approximately 57 times the normal value. Additionally, during the monitoring period, a drilling hole 20 m ahead of the working face recorded a drilling cuttings quantity of 1027 kg at 8 m depth, about 473 times the normal value. Another hole 59 m ahead of the working face recorded 1548 kg at 8 m depth, approximately 713 times the normal value. These are typical examples of the ultra-large drilling cuttings quantity phenomenon.

Characteristics of ultra-large drilling cuttings quantity

General patterns of ultra-large drilling cuttings quantity

Based on literature and field data analysis, the ultra-large drilling cuttings quantity phenomenon occurs under various hardness conditions. For example, it has been observed in both soft coal seams (e.g., a mine in Shenyang) and hard coal seams (e.g., Zhangshuanglou Coal Mine). It has also been reported in both deep and shallow mining operations. For instance, Zhangshuanglou Coal Mine first observed this phenomenon at -990 m, while a mine in Xinjiang recorded it at around − 350 m. Within the same mine, the phenomenon is more likely to occur in deeper mining areas. In the same drilling hole, the phenomenon typically occurs near the peak abutment pressure zone. For example, at the 7123 working face of Zhangshuanglou Coal Mine, the phenomenon was frequently observed at around 8 m depth (near the peak abutment pressure). The occurrence of ultra-large drilling cuttings quantity is often accompanied by dynamic phenomena such as noises, drill jamming, drill suction, and large coal particles.

Differences between ultra-large drilling cuttings quantity, hole collapse, and blowout

The drilling hole and its surrounding rock in coal seams form a deformable structure with stability issues. Under stable conditions, the hole wall remains intact, and the drilling cuttings quantity consists of the coal volume within the hole diameter and the volume generated by hole deformation, varying regularly with coal stress. However, when the coal stress reaches a critical value, the surrounding rock of the drilling hole transitions from a shallow plastic zone to a deep elastic zone, becoming unstable. Under disturbances such as drilling and rotation, the deformable structure of the hole and its surrounding rock becomes unstable, causing the plastic zone to expand continuously. The coal in the plastic zone flows into the roadway, resulting in a drilling hole impact phenomenon similar to roadway rockburst. This leads to a sudden, irregular increase in drilling cuttings quantity, i.e., the ultra-large drilling cuttings quantity phenomenon. Therefore, ultra-large drilling cuttings quantity can be regarded as the result of drilling hole impact, caused by stress and disturbances, and is characterized by suddenness.In contrast, hole collapse, similar to roadway roof fall, occurs when the surrounding coal undergoes shear failure, developing fractures that collapse under gravity, representing a progressive failure27. Blowouts, typically occurring in high-gas coal seams, are similar to coal and gas outbursts. They involve the ejection of broken coal from the hole under the combined action of gas pressure and stress, exhibiting distinct gas-related characteristics. Thus, the mechanisms behind ultra-large drilling cuttings quantity, hole collapse, and blowouts differ, leading to different increments in drilling cuttings quantity. Figure 3 illustrates the mechanisms of ultra-large drilling cuttings quantity, hole collapse, and blowout.

Theoretical analysis of ultra-large drilling cuttings quantity phenomenon

Plastic strain softening model for coal seam drilling holes

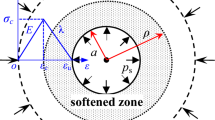

Assuming the coal wall in front of the drilling hole is a homogeneous, isotropic elastic body, the failure of the surrounding coal follows the Mohr-Coulomb yield criterion, and gravity is neglected, the problem can be treated as an axisymmetric plane strain under hydrostatic pressure. The drilling hole radius is denoted as a, the far-field stress as P, and the radius of the plastic zone as ρ. Outside the plastic zone lies the elastic zone, as shown in Fig. 4. To derive the initiation conditions for the ultra-large drilling cuttings quantity phenomenon, the constitutive relationship of coal deformation and failure is simplified as bilinear. Before peak strength, the deformation is linearly elastic with an elastic modulus E, and the peak strength corresponds to the uniaxial compressive strength σc and strain εc. After peak strength, the strain softening stage is simplified as a linear decline with an absolute slope equal to the softening modulus, as shown in Fig. 5.

The constitutive equation established based on Fig. 5 is as follows:

The equilibrium equation is as follows:

In the equation, σr and σθ represent the radial stress and tangential stress, respectively;

The geometric equation is as follows:

In the plastic zone near the wall of the drilling cuttings hole, it is assumed that the volume of coal is incompressible. For the plane strain problem, the following holds:

Substituting Eq. (3) into Eq. (4) yields:

Where B is the integration constant. Given the radial displacement at the borehole boundary r = a as ua, we have:

Based on the equivalent strain formula:

The effective strain in the plastic zone can be obtained as:

From the condition \(\bar {\varepsilon }\left( \rho \right)={\varepsilon _c}\), the contraction displacement of the borehole wall is derived as:

According to the analysis of the source of drilling cuttings in Sect. 1.2, combined with Eq. (9) and the expression for drilling cuttings quantity, the total drilling cuttings quantity \({M_0}\)per unit depth can be obtained as:

where γ is the unit weight of coal.

Let the stresses at the interface between the elastic and plastic zones be σr and σθ, then:

At the interface between the elastic and plastic zones, the coal is in the initial yield state. Using the Coulomb yield criterion:

Where \(m{\text{=}}\frac{{1{\text{+}}\sin \varphi }}{{1 - \sin \varphi }}\),and ϕ is the internal friction angle.

Assuming that damage evolution occurs in the softening zone, the damage variable D is linearly related to the equivalent strain \(\bar {\varepsilon }\), i.e.,\(D={D_1}+{D_2}\bar {\varepsilon }\). When \(\bar {\varepsilon }={\varepsilon _c}\),\(\bar {\sigma }={\sigma _c}\),\(D=0\) ; when \(\bar {\varepsilon }={\varepsilon _u}\),\(\bar {\sigma }=0\), where \(D={D_{cr}}\) is the critical damage value. Thus, we have:

Replacing the stress in Eq. (12) with effective stress:

Neglecting body forces, the equilibrium equation and yield condition in the plastic zone satisfy:

Solving this yields:

where R is the integration constant.

Combining Eq. (16) with the boundary conditions \({\sigma _r}\left( \rho \right)=\frac{{2P - {\sigma _c}}}{{1+m}}\) and \({\sigma _r}\left( a \right)=0\) we obtain:

Initiation conditions for the ultra-large drilling cuttings quantity phenomenon

The occurrence of the ultra-large drilling cuttings quantity phenomenon depends on whether the deformation structure of the surrounding rock of the drilling hole is stable. When disturbances such as roadway excavation, working face advancement, blasting, drill rod rotation, and advancement occur near the drilling hole, the deformation structure of the surrounding rock will inevitably be affected. If the deformation of the drilling hole caused by any disturbance is limited, the deformation structure of the surrounding rock remains stable. However, if the deformation structure becomes uncontrollable under any disturbance, the deformation structure of the surrounding rock is in an unstable state28.

For a drilling hole in equilibrium under the action of coal stress P, the drilling cuttings quantity is\({M_0}\). If a minor disturbance\(\Delta P\)to the coal stress P increases the drilling cuttings quantity from \({M_0}\) to\({M_0}{\text{+}}\Delta {M_0}\), and the response \({M_0}\)is finite, the equilibrium state of the coal wall is stable. The system simply transitions to a new equilibrium state after the disturbance. That is, for any given small number \(\varepsilon >0\), there exists a\(\delta >0\), such that when the disturbance \(\Delta P\) satisfies \(\left| {\Delta P} \right| \leqslant \delta\), the response \(\Delta {M_0}\) satisfies the inequality:

If the coal wall of the drilling hole is in an unstable equilibrium state, no matter how small the disturbance\(\Delta P\), it will lead to an infinite increase in the drilling cuttings quantity\(\Delta {M_0}\), i.e.,

Equation (19) represents the initiation condition for the ultra-large drilling cuttings quantity under the disturbance response instability theory.

From the stress continuity condition at the interface between the elastic and plastic zones (r=ρ), we obtain:

The solution is:

Substituting Eq. (22) into Eq. (17), the relationship between the drilling cuttings quantity and coal stress is obtained as: `

Taking the derivative of Eq. (23) with respect to the coal stress P, we get:

Based on Eq. (24) and Eq. (19), the critical stress for the initiation of the ultra-large drilling cuttings quantity can be derived as:

From Eq. (25), it can be seen that the initiation condition for the ultra-large drilling cuttings quantity is determined by the inherent physical and mechanical properties of the coal. When the actual coal stress P ≥ P∗, the ultra-large drilling cuttings quantity phenomenon can occur, and the drilling cuttings quantity far exceeds the normal value. Otherwise, the drilling hole remains stable, and the drilling cuttings quantity has a one-to-one correspondence with the stress.

When the coal stress reaches the critical stress, the critical value of the ultra-large drilling cuttings quantity can be obtained from Eq. (23) as:

Equation (26) reflects that the coal properties, burst propensity, and drilling hole size are the main factors influencing the critical value of the ultra-large drilling cuttings quantity.

Analysis of main influencing factors for the ultra-large drilling cuttings quantity phenomenon

The key criterion for judging the initiation of the ultra-large drilling cuttings quantity phenomenon is whether the coal stress reaches the critical stress. From Fig. 3 and the definition of bursting energy index KE, under ideal conditions, the ratio of the softening modulus λ to the elastic modulus E equals the bursting energy index KE. Therefore, λ/E can be approximated as the bursting energy index KE. From Eqs. (25) and (26), it can be seen that the bursting energy index KE, uniaxial compressive strength σc, and unit weight γ are the factors controlling the ultra-large drilling cuttings quantity and its critical stress. Based on Eq. (23), the relationship between drilling cuttings quantity and coal stress under different values of bursting energy index KE, compressive strength σc, and unit weight is plotted, as shown in Figs. 6, 7 and 8. According to the mechanism of the ultra-large drilling cuttings quantity phenomenon, once the stress in the surrounding rock of the drilling hole reaches the critical stress, the drilling hole becomes unstable, and the drilling cuttings quantity increases disorderly. Therefore, to represent the disordered increase in drilling cuttings quantity beyond the critical stress, an upward straight line is used in the plots. According to the mechanism of ultra-large drilling cuttings quantity, when the surrounding rock stress of the borehole reaches the critical stress, the borehole becomes unstable, and the plastic zone undergoes theoretically uncontrollable expansion, triggering a disordered increase in drilling cuttings quantity. In practice, the expansion of the plastic zone does not continue indefinitely but ceases once the system structure enters a new stability point. However, due to the uncertainty in the spatiotemporal distribution of these stability points, the magnitude of ultra-large drilling cuttings quantity remains finite.

Influence of the bursting energy index K E

Figure 6 illustrates the variation of drilling cuttings quantity with coal stress P under different bursting energy index KE. It can be observed that as the coal stress increases, the drilling cuttings quantity also increases. However, once the stress reaches a certain critical value, the drilling cuttings quantity no longer increases in a regular manner but rather exhibits disordered growth due to instability. This critical stress value represents the threshold at which the drilling hole becomes unstable, leading to the occurrence of the ultra-large drilling cuttings quantity phenomenon.

By analyzing Eq. (25) in conjunction with Fig. 6, it is evident that when the brittleness of the coal seam is stronger, the softening modulus λ is larger, resulting in a higher bursting energy index KE and greater impact tendency. Consequently, the critical stress for the ultra-large drilling cuttings quantity phenomenon decreases, making it easier for the phenomenon to initiate. Conversely, when λ is smaller, the bursting energy index KE decreases, the impact tendency diminishes, and the critical stress for the ultra-large drilling cuttings quantity phenomenon increases, making it less likely to occur.In the extreme case, When λ approaches infinity, the bursting energy index KE also approaches infinity. In this scenario, the ultra-large drilling cuttings quantity phenomenon can occur when the coal stress P reaches half of the uniaxial compressive strength σc. When λ is zero, the bursting energy index KE becomes zero, and the coal behaves as an ideal elastic-plastic material. In this case, the critical stress for the ultra-large drilling cuttings quantity phenomenon approaches infinity, meaning the phenomenon will never occur.

Figure 7 illustrates the relationship between the critical drilling cuttings quantity, critical drilling cuttings stress, and the bursting energy index KE. It can be observed that as the bursting energy index KE increases, both the critical drilling cuttings quantity and the critical drilling cuttings stress decrease. Overall, there is a negative correlation between KE and the critical drilling cuttings quantity as well as the critical drilling cuttings stress. However, the sensitivity of the critical drilling cuttings quantity and critical drilling cuttings stress to changes in KE differs significantly before and after KE=1.Before KE=1, as the bursting energy index KE decreases, the absolute value of the slope of the curves for the critical drilling cuttings quantity and critical drilling cuttings stress increases. This indicates that the critical drilling cuttings quantity and critical drilling cuttings stress are highly sensitive to changes in KE in this range. In other words, for coal with lower KE values, small changes in KE lead to significant changes in the critical drilling cuttings quantity and critical drilling cuttings stress.After KE=1,as the bursting energy index KE increases, the absolute value of the slope of the curves for the critical drilling cuttings quantity and critical drilling cuttings stress decreases. This suggests that the critical drilling cuttings quantity and critical drilling cuttings stress become less sensitive to changes in KE for brittle coal with higher KE values. In other words, for coal with higher KE values, changes in KE have a relatively smaller impact on the critical drilling cuttings quantity and critical drilling cuttings stress. In summary, the relationship between the bursting energy index KE and the critical drilling cuttings quantity as well as the critical drilling cuttings stress is characterized by a negative correlation. However, the sensitivity of these critical values to changes in KE varies significantly depending on whether KE is below or above 1. For KE<1, the critical values are highly sensitive to changes in KE, while for KE>1, the critical values become less sensitive, particularly for brittle coal.

In the equation, b represents the radius of the roadway, and ρcr is the critical depth of the softening zone

According to reference28, Eq. (27) provides the calculation formula for the critical depth of the softening zone at which rockburst occurs. When the roadway radius remains constant, the more brittle the coal, the higher the bursting energy index KE, and the smaller the critical depth of the softening zone, making rockburst more likely to occur. Combined with Fig. 7, the influence of the bursting energy index KE on rockburst and the ultra-large drilling cuttings quantity follows the same pattern, indicating that the ultra-large drilling cuttings quantity phenomenon can serve as a dynamic indicator for predicting rockburst.

Influence of uniaxial compressive strength Σc

Figure 8 illustrates the variation of drilling cuttings quantity with coal stress P under different values of uniaxial compressive strength σc. Similarly, once the coal stress reaches the critical stress, the drilling cuttings quantity enters a state of disordered growth due to instability.

From the different values of uniaxial compressive strength σc, it can be observed that the larger the σc, the greater the critical value and critical stress for the ultra-large drilling cuttings quantity phenomenon. This indicates that the higher the uniaxial compressive strength σc, the more difficult it is to initiate the ultra-large drilling cuttings quantity phenomenon. However, once initiated, as the amount of discharged cuttings increases, the severity of the situation escalates. This explains why the ultra-large drilling cuttings quantity phenomenon often occurs in soft coal but is more severe when it occurs in hard coal. For example, the hardness coefficient of the No. 7 coal seam in Zhangshuanglou Coal Mine is 2.3, which is classified as hard coal. Therefore, the ultra-large drilling cuttings quantity phenomenon is more severe in this case.

Influence of unit weight

Figure 9 illustrates the variation of drilling cuttings quantity with coal stress P under different unit weight conditions.

From Fig. 9, it can be observed that an increase in unit weight does not alter the critical stress for the ultra-large drilling cuttings quantity phenomenon. However, it increases the drilling cuttings quantity under the same stress conditions and raises the critical value for the ultra-large drilling cuttings quantity. This indicates that changes in the unit weight of the coal do not affect the ease of initiating the ultra-large drilling cuttings quantity phenomenon or the rate of change in drilling cuttings quantity caused by variations in coal stress.

Field application and analysis

Based on physical and mechanical experiments, the physical and mechanical parameters of the No. 7 coal seam in the Zhangshuanglou Coal Mine are presented in Table 1. Using Eqs. (23), (25), and (26), the relationship between the drilling cuttings quantity and coal stress for Zhangshuanglou Coal Mine can be derived, as illustrated in Fig. 10.

From Fig. 10, it can be observed that the critical stress for the occurrence of the ultra-large drilling cuttings quantity phenomenon in the No.7 coal seam of Zhangshuanglou Coal Mine is 44.6 MPa. Based on the geological and mining technical conditions of the 7123 working face in Zhangshuanglou Coal Mine, the burial depth H at the location where the ultra-large drilling cuttings quantity occurred is approximately 950 m. The unit weight of the overlying strata is taken as 25kN/m³, the stress concentration coefficient k0 for the advance influence of the working face is 1.6, and the stress concentration coefficient k1 for the lateral abutment pressure of the roadway is 1.2. The actual stress P0 at the location where the ultra-large drilling cuttings quantity occurred can be estimated as:

\(P0=H \times \gamma \times ({k_0}+{k_1} - 1)=42.75\operatorname{MPa}\)

It can be seen that the estimated actual stress differs from the theoretical calculation by approximately 4%, which is a negligible difference. Additionally, the trend of drilling cuttings quantity with depth at the measurement points of the ultra-large drilling cuttings quantity in Fig. 11 matches that in Fig. 10, indicating that the theoretical derivation aligns well with the actual conditions.

For the area in Fig. 10 where the ultra-large drilling cuttings quantity occurred, pressure relief blasting was conducted. After the blasting, three drilling inspection holes were constructed, and it was found that the drilling cuttings quantity still exceeded the standard. A second round of pressure relief blasting was performed, and subsequent inspections showed that the drilling cuttings quantity returned to normal, as illustrated in Fig. 11. It took two rounds of intensive pressure relief for the area to return to normal, indicating that the region where the ultra-large drilling cuttings quantity phenomenon occurred was under high stress and at significant risk of rockburst. This further demonstrates that the ultra-large drilling cuttings quantity phenomenon can be used to assess the risk of roadway rockburst.

Discuss

In this study, a plastic strain softening model for coal seam drilling holes is established. And the analytical solution for the initiation conditions of the ultra-large drilling cuttings quantity phenomenon is derived. Then, the controlling factors for the critical stress of ultra-large drilling cuttings in coal were analyzed, and it was found that the bursting energy index KE and uniaxial compressive strength σc have a significant impact on the critical stress of ultra large drilling cuttings in coal.

Extensive research has shown that the external cause of rockburst in roadways is stress concentration in the coal body due to mining activities, while the internal cause lies in the physical and mechanical properties of the coal itself29,30. As indicated by Eqs. (25) and (26), the ultra-large drilling cuttings quantity phenomenon is influenced by the physical and mechanical properties of the coal and occurs when the coal stress reaches the critical stress for the phenomenon. Therefore, both the ultra-large drilling cuttings quantity and roadway rockburst are controlled by the same factors, suggesting a certain relationship between the ultra-large drilling cuttings quantity phenomenon and the risk of roadway rockburst.

Reference28 provides the initiation conditions for roadway rockburst. A comparison with the initiation conditions for the ultra-large drilling cuttings quantity reveals that the critical stress for initiating roadway rockburst is the same as that for initiating the ultra-large drilling cuttings quantity. Both are determined by the physical and mechanical properties of the coal and share the same value. Thus, when the ultra-large drilling cuttings quantity phenomenon occurs in a drilling hole, the stress in the surrounding rock of the drilling hole reaches the critical stress for initiating the phenomenon. Since the stress in the surrounding rock of the drilling hole represents the stress in the surrounding rock of the roadway, this implies that the roadway stress has reached the critical level for rockburst occurrence. At this point, the roadway is at risk of rockburst.Therefore, the occurrence of the ultra-large drilling cuttings quantity phenomenon can be used to assess a high risk of rockburst in the drilling area. Similar to dynamic phenomena such as vibrations, noises, and drill jamming, the ultra-large drilling cuttings quantity phenomenon serves as an early warning indicator for rockburst risk during drilling. However, it reflects a localized state of excessive stress in the coal and is a sufficient but not necessary condition for rockburst occurrence.

Conclusions

(1) The definition of the ultra-large drilling cuttings quantity phenomenon is provided. Based on the analysis of its initiation conditions, it is found that this phenomenon can occur under various conditions, including coal seams of different strengths and at different mining depths.

(2) A plastic strain softening model for coal seam drilling holes is established. Based on the disturbance response instability theory, the analytical solution for the initiation conditions of the ultra-large drilling cuttings quantity phenomenon is derived, including the formulas for the critical value and critical stress of the phenomenon.

(3) Analysis of the influencing factors of the ultra-large drilling cuttings quantity reveals that the bursting energy index KE and uniaxial compressive strength σc significantly affect both the critical value and critical stress of the phenomenon. In contrast, the unit weight primarily influences the critical value.

(4) The relationship between the ultra-large drilling cuttings quantity and rockburst is analyzed. It is found that both phenomena are controlled by the same factors. The occurrence of the ultra-large drilling cuttings quantity phenomenon indicates that the stress in the surrounding rock of the roadway has reached the critical condition for rockburst, placing the roadway in a state of rockburst risk. Furthermore, based on the actual conditions of Zhangshuanglou Coal Mine, the theoretically calculated stress at the occurrence of the ultra-large drilling cuttings quantity closely matches the estimated actual stress. This comprehensive analysis demonstrates that the ultra-large drilling cuttings quantity phenomenon can serve as a dynamic indicator for assessing rockburst risk during drilling operations.

Data availability

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Abbreviations

- a:

-

Drilling hole radius, m

- b:

-

Roadway radius, m

- B:

-

Integration constant

- E :

-

Elastic modulus, MPa

- D :

-

Damage variable

- γ :

-

Unit weight of coal, kg/m2

- H:

-

Burial depth, m

- R:

-

Integral constant

- KE :

-

Bursting energy index

- λ :

-

Softening modulus, MPa

- P :

-

Coal stress, MPa

- P* :

-

Critical stress for starting with a large amount of drill cuttings in coal

- ρ :

-

Radius of the plastic zone, m

- σc :

-

Uniaxial compressive strength, MPa

- ua :

-

Radial displacement at the borehole boundary, m

- M 0 :

-

Quantity of drill cuttings

- M 0 * :

-

critical value of ultra large amount of drill cuttings in coal body

References

Feng, X. et al. Evolution law and risk analysis of fault-slip burst in coal mine based on microseismic monitoring. Environ. Earth Sci. 84 (2), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12665-024-12080-5 (2025).

Jiang, B. et al. Development of physical model test system for fault-slip induced rockburst in underground coal mining. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. in press. (2024). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrmge.2024.04.003

Tan, Y. et al. Main control factors of rock burst and its disaster evolution mechanism. J. China Coal Soc. 49 (2), 367–379. https://doi.org/10.13225/j.cnki.jccs.2023.0829 (2024).

Li, X. et al. Roadway portal and self-moving hydraulic support for rockburst prevention in coal mine and its application. Phys. Fluids. 36 (12), 1201–1210. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0243798 (2024).

Zhao, X. et al. Influence of pre-existing crack on rockburst characteristics in coal-rock combination: A laboratory investigation. Int. J. Rock. Mech. Min. Sci. 178 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmms.2024.105753 (2024).

Du, K. et al. Occurrence mechanism and prevention technology of rockburst, coal bump and mine earthquake in deep mining. Geomech. Geophys. Geo-Energy Geo-Resour. 10, 1–35. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40948-024-00768-8 (2024).

Liu, X. et al. Compound disaster characteristics of rock burst and coal spontaneous combustion in Island mining face: A case study. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 63, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csite.2024.105240 (2024).

Zhang, W. et al. A new monitoring-while-drilling method of large diameter drilling in underground coal mine and their application. Meas. 173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.measurement.2020.108840 (2021).

Dou, L. et al. Research progress of monitoring, forecasting, and prevention of rockburst in underground coal mining in China. Int. J. Coal Sci. Technol. 1 (3), 278–288. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40789-014-0044-z (2014).

Cao, B. & Zhang, Y. Early warning method of rock burst based on variation of drilling cuttings. Coal Mine Mod. 30 (3), 80–82. https://doi.org/10.13606/j.cnki.37-1205/td.2021.03.026 (2021).

Zhu, G. et al. Experimental study on critical index optimization of drilling cuttings method of water-bearing coal based on acoustic emission features. J. China Coal Soc. 48 (12), 4433–4442. https://doi.org/10.13225/j.cnki.jccs.2023.0141 (2023).

Hao, Z., Li, Z. & Pan, Y. Influence of water injection on burst-prone coal seam during drilling. Coal Geol. Explor. 48 (3), 231–238. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1001-1986.2020.03.033 (2020).

Standardization Administration of China (SAC). GB/T 25217.6–2019: Determination, Monitoring and Prevention of Rock Burst Pressure – Part 6: Drilling Cuttings Method (China Standards, 2019).

State Administration of Work Safety. Regulations on preventing coal and gas outburst. Lab. Prot. 30 (4), 115–125 (2009).

Pan, Y. A study of the theory of drilling method. J. Fuxin Inst. Min. Technol. 10, 95–101 (1985).

Wen, G. & Wang, X. Discussion on the coal and gas outburst prediction of drilling cuttings. Coal Eng. (3), 32–34 (1998).

Cui, N., Li, Z. & Pan, Y. Study on index of drilling Bits for coalbed rockburst influenced by gas. J. Liaoning Tech. Univ. 25 (2), 192–193. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1008-0562.2006.02.010 (2006).

Li, Z. Study on theory and application of high gassy seam rockburst [PhD Dissertation]. Liaoning technical university, (2007).

Yin, G. et al. In-situ experimental study on the relation of drilling cuttings weight to ground pressure and gas pressure. J. Eng. Sci. 32 (1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.13374/j.issn1001-053x.2010.01.004 (2010).

Qu, X. et al. Rockburst monitoring and precaution technology based on equivalent drilling research and its applications. Chin. J. Rock. Mech. Eng. 30 (11), 2346–2351. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12583-011-0163-z (2011).

Yin, Y., Jiang, F. & Zhu, Q. Rockburst real-time wireless monitoring and early warning technology in heading face. Saf. Coal Mines. 45 (3), 88–91. https://doi.org/10.13347/j.cnki.mkaq.2014.03.026 (2014).

Tang, J., Chen, S. & Li, W. Theoretical and experimental studies on drilling cutting weight considering effective stress. J. Geotech. Eng. 40 (1), 130–138. https://doi.org/10.11779/CJGE201801013 (2018).

Tang, J., Chen, S. & Yu, N. Research on drilling cuttings quantity index of coal and gas outburst based on average effective stress. Prog Geophys. 32 (1), 395–400. https://doi.org/10.6038/pg20170156 (2017).

Cook, N. G. W. The failure of Rock.Int. J. Rock. Mech. Min. Sci. Geomech. Abstr. 2, 389–403. https://doi.org/10.1016/0148-9062(65)90004-5 (1965).

Yin, Y. et al. Automatic measurement method of drilling-cuttings of boreholes in the coal seam and test study. Coal Sci. Technol. 51 (11), 23–32. https://doi.org/10.12438/cst.2022-2006 (2023).

Zhu, G. et al. Experimental study on critical index optimization of drilling cuttings method of water-bearing coal based on acoustic emission features. J. Rock. Mech. Eng. 41 (12), 2417–2431. https://doi.org/10.13722/j.cnki.jrme.2022.0215 (2022).

Cheng, R. et al. Research on hole collapse monitoring technology of coal seam gas extraction boreholes. Sustainability 15, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151310262 (2023).

Pan, Y. et al. Coalbursts in China: theory, practice and management. J. Rock. Mech. Geotech. Eng. 16 (1), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.13225/j.cnki.jccs.2023.0294 (2024).

Wang, J. et al. Prediction of strainburst risks based on the stiffness theory: development and verification of a new rockburst indicator.int. J. Rock. Mech. Min. Sci. 175, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmms.2024.105667 (2024).

Feng, X. et al. Numerical study on the influence of fault orientation on risk level of fault slip burst disasters in coal mines: A quantitative evaluation model. Environ. Earth Sci. 83 (1), 94. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12665-023-11399-9 (2024).

Funding

This study was funded by the Basic Research Project of Liaoning Provincial Department of Education (JYTMS20230769). The authors also thank anonymous colleagues for their kind efforts and valuable comments in improving this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Writing—review and editing, T.S. and W.Z.; visualization, W.Z.; funding acquisition, Y.P. and T.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zheng, W., Pan, Y. & Shi, T. Study on the phenomenon of the ultra-large drilling cuttings quantity in rockburst coal seam. Sci Rep 15, 11686 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96295-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96295-x