Abstract

A diode-pumped continuous-wave (CW) orthogonally polarized dual-wavelength (OPDW) Nd:SrAl12O19/Nd:LaMgAl11O19 (Nd:SA/Nd:LMA) laser at 898 and 904 nm with tunable power ratio on 4F3/2 → 4I9/2 quasi-three-level transition is demonstrated for the first time. The pump wavelength and the waist position of the pump beam were optimized to achieve high efficiency and balanced output powers of OPDW laser. The OPDW laser at 898 and 904 nm was obtained with the highest total output power of 6.59 W and the power ratio of 1:1. The highest total slope efficiency and total optical-to-optical conversion efficiency related to the absorbed pump power at 796.85 nm were 39.7% and 36.2%, respectively. The OPDW laser at 898 and 904 nm has important application prospects in fields such as biomedicine, scientific research, gas detection, and remote sensing technology.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The CW OPDW lasers have a wide range of applications in many fields, such as radars1, medical detection2, holography3,4, imaging and neural network5, metrology6,7, visible to ultraviolet lights generation by nonlinear sum-frequency mixing8,9, and terahertz-wave generation by difference-frequency mixing10. In particular, OPDW lasers in the 0.9 μm regions11,12 have attracted a lot of attention due to their applications in biomedicine, scientific research, gas detection and remote sensing technology13,14. However, Nd-doped quasi-three-level OPDW laser emissions were reported rarely. The main reason was that the closer the transition was to the ground state, the harder it was to reach the population inversion, and there was strong reabsorption at transition wavelengths close to the ground state15,16,17. For example, a 2.1 W of CW total output power at 914 and 915 nm in the Nd:YVO4 was obtained with 17.1% of total optical-to-optical conversion efficiency in 201411. Recently, an OPDW laser at 903 and 908 nm was realized in the Nd:YLF with 12.0% of total optical-to-optical conversion efficiency12. The above quasi-three-level OPDW lasers were all obtained in the same gain medium. However, due to the strong gain competition between the two transition emission lines, it is difficult to achieve high conversion efficiency and good power stability. In addition, the output power ratio cannot be adjusted, which limits the application of the OPDW lasers.

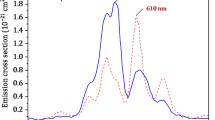

The Nd:LMA and Nd:SA crystals have demonstrated wide spectral linewidths, moderate emission cross-sections and high luminescent quantum efficiency, making the Nd:LMA and Nd:SA crystals an excellent gain media of the solid-state lasers, and the lasers operating at 1.05 μm in the Nd:SA or Nd:LMA crystals were also realized on 4F3/2 → 4I11/2 transition18,19. To the best of our knowledge, the Nd:SA or Nd:LMA lasers on the 4F3/2 → 4I9/2 transition have not been studied until now. Figure 1 shows the polarized emission cross-sections of the Nd:SA and Nd:LMA crystals on the 4F3/2 → 4I9/2 transition, which was calculated by the Füchtbauer–Ladenburg Equation20. As shown in Fig. 1, the emission cross sections in σ-polarization are much larger than in π-polarization for both crystals, and the strongest emission peaks of the Nd:SA and Nd:LMA crystals are 898 and 904 nm in the direction of the σ-polarization, respectively. The corresponding energy structures of the Nd:SA and Nd:LMA crystals are shown in Fig. 2. As can be seen from Fig. 2a, the 4F3/2 → 4I11/2, 4F3/2 → 4I13/2 and 4F3/2 → 4I9/2 transitions of the Nd:SA crystal produce emission peak wavelengths of 1049 nm, 1297 nm and 898 nm, respectively. As can be seen from Fig. 2b, the emission peak wavelengths at 1055 nm, 1306 nm and 904 nm are produced by the transitions from the 4F3/2 → 4I11/2, 4F3/2 → 4I13/2 and 4F3/2 → 4I9/2 transitions of the Nd:LMA crystal, respectively.

It was worth mentioning that the main absorption peaks of Nd:SA and Nd:LMA crystals was in the 780–800 nm region, and there was no absorption peaks in the 890–910 nm range18,19, which was very favorable for obtaining quasi-three-level lasers. The DW lasers usually include the intracavity loss elements such as specially coated output couplers21,22,23,24,25,26, etalons27,28,29 or birefringent filters30,31,32 to balance the gains and losses between the two laser wavelengths. However, one of the main difficulties with these DW lasers was that the ratio of output powers between the two transition lines could be adjusted. To solve these problems, an effective solution was to replace a single gain medium with a compound gain medium. At present, there are three methods to adjust the ratio of output powers of two laser wavelengths. The first method is to change the axial position of the waist of pump beam in the composite gain medium33. The second method is to use a wedged-bonded gain medium and then changes the lateral position of the pump waist within the gain medium34. The third method is to adjust the pump wavelength to change the absorption ratio of the pump power in the bonded crystal35. Using the three methods above, the DW lasers operating at 1.06 μm on the 4F3/2 → 4I11/2 transition had been reported for the compound gain medium33,34,35. In this work, a CW OPDW Nd:SA /Nd:LMA laser at 898 and 904 nm on 4F3/2 → 4I9/2 transition was realized. The ratio of the OPDW output powers was controlled by the best calculated pump waist position and adjusting the pump wavelength. The total output power of the 898 and 904 nm OPDW laser reached 6.59 W, and the corresponding total slope efficiency and total optical-to-optical conversion efficiency with respect to the absorbed pump power at 796.85 nm were 39.7% and 36.2%, respectively.

Experimental setup

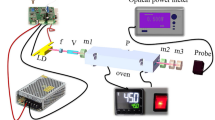

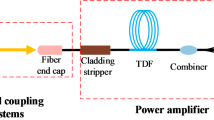

A schematic setup for the CW OPDW Nd:SA/Nd:LMA laser at 898 and 904 nm is shown in Fig. 3. The laser pump source was a laser diode (LD) by fiber coupling (400 μm core diameter, numerical aperture = 0.22, M2 = 45) operating in the 791.1–798.2 nm range with a maximum output power of 18.7 W. The temperature of the LD was cooled by the thermoelectric cooler. The temperature was monitored using the thermistor and was set to operate between 16 and 38 °C. The combination of the two identical convex lenses (L1 and L2) was the coupling system of the pump beam. The L1 and L2 have the same focal length (= 50 mm), which were antireflection (AR) coated at 790–800 nm. The concave mirror (M1) with the radius of curvature of − 300 mm was the input coupler, which was AR coated at 790–800 nm, 1040–1060 nm, and high reflectivity (HR) coated at 895–905 nm. The gain medium of the OPDW laser was a combination of two independent Nd:SA and Nd:LMA crystals. The Nd:SA with a-cut, 5 mm long and 1.0 at.% doped Nd3+ and Nd:LMA with a-cut,10 mm long and 2.0 at.% doped Nd3+ were AR coated at 790–800 nm, 895–905 nm and 1040–1060 nm. The c-axis of the Nd:SA and Nd:LMA was perpendicular to each other, thus the two σ-polarizations of the 898 nm (S-wave) and 904 nm lasers (P-wave) generated by the Nd:LMA and Nd:SA crystals, respectively, were orthogonal. The two crystals were individually wrapped in indium foil and mounted on water-cooled copper blocks at the temperature of 16 °C. The plane mirror (M2) was the output coupler, which was with a transmittance of 2.7% at 895–905 nm and AR at 1040–1060 nm. The three output couplers (1.5, 2.7 and 4.0%) were used and the best performance was realize using the output coupler of 2.7%.

Results and discussion

The absorption cross sections in region of 786–804 nm, σabs,i, were calculated by the Judd–Ofelt theory36 and the relevant parameters18,19,37,38, as shown in Fig. 4a. We calculated the absorption efficiencies, ηabs,i = 1– exp(–αili), of the Nd:SA and Nd:LMA crystals in region of 786–804 nm, as shown in Fig. 4b, where i = 898 and 904 represents 898 and 904 nm wavelengths, respectively, αi = σabs,i Ni, N is Nd3+ concentration in units of ion/cm3 (N898 = 3.37 × 1019 cm−3 for 1.0 at.% Nd3+ doped (Nion) SA crystal and N904 = 5.90 × 1019 cm−3 for 2.0 at.% Nd3+ doped LMA crystal), and l is the length of the gain medium. To balance the output power generated by the Nd:SA and Nd:LMA crystals, the pump power was selected to be absorbed first by the Nd:SA crystal with the lower absorption efficiency, and then the remaining pump power was absorbed by the Nd:LMA crystal with the high absorption efficiency. To adjust the ratio of the OPDW output powers, it can be achieved by tuning the pump wavelength or controlling the pump waist position. The measured pump peak wavelength versus working temperature of the LD is shown in the inset of Fig. 4b. As shown in the inset of Fig. 4b, the pump peak wavelength could be changed from 791.1 to 798.2 nm when the working temperature of the LD was regulated from 16 to 38 °C.

The CW output power, Pout,i, for an end-pumped solid-state laser system can be expressed as39

where Toc is the transmittance of the output coupler, L is the cavity round-trip loss,\(v\) is the frequency of the emission-wavelength, \({v}_{p}\) is the frequency of the pump wavelength,\({P}_{abs}\) is the absorbed pump power, and \({P}_{tha}\) is the absorbed pump threshold, which for the quasi-three-level laser system can be written as40

σ is the cross section of the emission wavelength, fa and fb are the population numbers in the Stark components of the upper and lower laser levels, respectively, ηQ is the laser quantum efficiency, τ is the fluorescence lifetime, \({\omega }_{p}(z)\) is the radius of the pump beam, which can be given by Siegman and Townsend41

where M2 is the quality factor of the pump beam, λp is pump wavelength, n is the refraction index of the gain medium, ωp0 is the waist radius of the pump beam, z0 is the pump waist position, and z0 = 0 was set at the interface between the Nd:LMA and Nd:SA crystals, \(\omega (z)\) is the radius of the beam at the emission wavelength, which was affected by the thermal lens effect of the Nd:SA and Nd:LMA crystals and can be calculated by the ABCD matrix. The focal lengths of the thermal lens for the gain medium can be calculated as42

where Kc is the thermal conductivity, ξ is the fractional heat load and dn/dT is the thermal-optic coefficient. The parameters in the experiment: \({\xi }_{898}=11.3\%,\) \({\xi }_{904}=11.9\%,\) Kc, 898 = 6.14 W/m K (for 1.0 at.% Nd3+-doped SA), Kc, 904 = 6.53 W/m·K (for 2.0 at.% Nd3+-doped LMA), \({(dn/dT)}_{898}\)= 3.65 × 10−6 K−1, \({(dn/dT)}_{904}\)= 4.06 × 10−6 K−1, and λp = 796.85 nm. At a pump wavelength of 796.85 nm, the maximum absorbed powers of the Nd:SA and Nd:LMA crystals were 7.4 W (= 39.6% × 18.7 W) and 10.8 W (= 61.4% × 18.7 W × 94.1%), respectively. The values of the Kc were measured by the method in Ref.43, and the values of the \(dn/dT\) were calculated by the method in Ref.44.

With Eq. (4) and the above parameters, the thermal lens focal lengths of the Nd:SA and Nd:LMA crystals with respect to the waist position of pump beam were calculated, as shown in Fig. 5a. According to the ABCD matrix and the stable region condition of the laser cavity, the beam sizes in crystals with cavity length were calculated, as shown in Fig. 5b. As can be seen from Fig. 5b, the two curve have a point of intersection, which corresponds to the cavity length (about 170 mm) and the radius (about 190 μm) in two crystals are equal. At this point, the optimum mode matching between the OPDW laser and pump beams can be achieved. It can be seen in Fig. 5a that a shift in the waist position of the pump beam causes a change in the thermal lens focal length of the two crystals. Since the two curve were calculated at a fixed pump wavelength, the mode mismatch between the laser and the pump beam may be caused when the pump wavelength changes. Therefore, it was necessary to adjust the cavity length so that the pump and the laser beams can meet the best mode matching when changing the pump wavelength.

When the LD temperature was 32.6 °C, νp = 3.76 × 1014 Hz, ηabs, 898 = 38.6%, ηabs, 904 = 94.1%, with Eqs. (1)–(4) and the parameters: T = 0.027, ν898 = 3.31 × 1014 Hz, ν904 = 3.03 × 1014 Hz, σ898 = 2.26 × 10−20 cm2, σ904 = 1.57 × 10−20 cm2, L898 = L904 = 0.05, fa,898 = fa,904 ≈ 0.5, fb,898 = fa,904 ≈ 0.052, τ898 = 401 μs18, τ904 = 436 μs19, M2 = 45, λp = 796.85 nm, n898 = 2.13, n904 = 2.21 and ηQ, 898 ≈ η Q, 904 = 0.88, the laser output powers of 898 nm (S wave) and 904 nm (P wave) were calculated as a function of waist position of pump beam, as shown in Fig. 6. It can be seen in Fig. 6 that the power of each wavelength firstly increases and then decreases, when the pump beam waist is moved from the front of the Nd:SA crystal towards the end of the Nd:LMA crystal. The balanced output power was generated at z = 2.5 mm, when the working temperature of the LD was 32.6 °C. Moving the pump waist position from this point (z = 2.5 mm) to both sides can adjust the output power ratio of the OPDW laser. The pump beam waist moving to the left from this point would cause the 904 nm laser output power to gradually decrease. This can be explained by the higher gain of the Nd:SA crystal compared to the Nd:LMA crystal when the pump beam waist was to the left of this point. Conversely, the pump beam waist moves to the right from this point, resulting in a gradual decrease in the output power of the 898 nm laser. Therefore, the optimal excitation of both crystals took place at z = 2.5 mm and in other situations only one of the crystals was effectively excited and contributed to the lasing process. The output powers of 898 nm and 904 nm were measured at the different waist position of pump beam, also as shown in Fig. 6. It can be seen in Fig. 6 that the measured output powers were in agreement with the simulated value. The pump waist position was retained at z = 2.5 mm, and the output powers of 898 nm and 904 nm were measured with the change of working temperature of the LD, as shown in Fig. 7. As can be seen in Fig. 7, the output power of 898 nm was greater than that of 904 nm when the working temperature was below 18.2 °C or above 32.6 °C. This was mainly because the Nd:SA crystal was excited more efficiently and involved in the main lasing process than Nd:LMA crystal within this working temperature range. Conversely, when the working temperature between 18.2 and 32.6 °C, the output power characteristics of 898 and 904 nm were opposite. The output spectra of the OPDW laser at different working temperature of LD of 24 °C, 32.6 °C and 38 °C were shown in Fig. 8.

The total output power of the OPDW Nd:LMA/Nd:SA laser at 898 and 904 nm versus the absorbed pump power at 796.85 nm is shown in Fig. 9. The maximum total output power was 6.59 W with the power ratio of 1:1 at 18.2 W of the absorbed pump power. This was basically consistent with the calculated results in Fig. 5 when the output powers of the two wavelengths were equal. The corresponding slope efficiency and optical-to-optical conversion efficiency were 39.7% and 36.2%, respectively. The M2 factors were less than 1.13 in both directions at the maximum total output power. The inset (a) of Fig. 9 shows the measured radii, shape and the M2 factors of output beam. The stability testing was carried out by monitoring the output powers of each wavelength with a Field-Master-GS power meter at 10 Hz. The fluctuations for 898 nm and 904 nm lasers at the maximum total output power were about 2.62% and 2.53% (RMS) in 1 h, respectively, as shown in the inset (b) of Fig. 9. The output power fluctuation should be caused by the periodical drift of the actual LD temperature, which was stabilized by a proportion integration differentiation circuit dynamically. However, this power stability was significantly better than that of quasi-three-level OPDW lasers with the single gain medium (about 5.0%). The main reason was that the use of two gain media avoids gain competition between the two wavelengths. By improving the temperature control device of LD, the power stability of the OPDW laser can be further improved.

Conclusion

A CW OPDW Nd:SA/Nd:LMA quasi-three-level laser at 898 and 904 nm on the 4F3/2 → 4I9/2 transition was realized using in-band LD pumping with tunable peak wavelength from 791.1 to 798.2 nm for the first time. The pump wavelength and the waist position of the pump beam were optimized to achieve high efficiency and balanced output powers of OPDW laser. The CW OPDW laser at 898 and 904 nm was obtained with the highest total output power of 6.59 W and the power ratio of 1:1. The highest total slope efficiency and total optical-to-optical conversion efficiency with respect to the absorbed pump power at 796.85 nm were 39.7% and 36.2%, respectively. We believe that the same technique presented in this paper can be applied to other composite crystals to achieve the OPDW lasers with adjustable ratio of output powers.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Farley, R. & Dao, P. Development of an intracavity-summed multiple-wavelength Nd:YAG laser for a rugged, solid-state sodium lidar system. Appl. Opt. 34, 4269–4273 (1995).

Derayea, S. M. et al. Novel eco-friendly HPTLC method using dual-wavelength detection for simultaneous quantification of duloxetine and tadalafil with greenness evaluation and application in human plasma. Sci Rep 14, 23907 (2024).

Abdelsalam, D., Magnusson, R. & Kim, D. Single-shot, dual-wavelength digital holography based on polarizing separation. Appl. Opt. 50, 3360–3368 (2011).

Weigl, F. A generalized technique of two-wavelength, nondiffuse holographic interferometry. Appl. Opt. 10, 187–192 (1971).

Ye, H. & Guo, D. Correlation reconstruction mechanism based on dual wavelength imaging and neural network. Sci. Rep. 14, 18241 (2024).

Louyer, Y. et al. Nd:YLF laser at 1.3 μm for calcium atom optical clocks and precision spectroscopy of hydrogenic systems. Appl. Opt. 42, 4867–4870 (2003).

Zhang, S., Tan, Y. & Li, Y. Orthogonally polarized dual frequency lasers and applications in self-sensing metrology. Meas. Sci. Technol. 21, 054016 (2010).

Lü, Y., Sun, G., Fu, X., Liu, Z. & Chen, J. Diode-pumped doubly resonant all-intracavity continuous-wave ultraviolet laser at 336 nm. Laser Phys. Lett. 7, 560–562 (2010).

Lü, Y., Zhai, P., Xia, J., Fu, X. & Li, S. Simultaneous orthogonal polarized dual-wavelength continuous-wave laser operation at 1079.5 nm and 1064.5 nm in Nd:YAlO3 and their sum-frequency mixing. J. Opt. Soc. AM. B 29, 2352–2356 (2012).

Dong, K. et al. Dual-wavelength transmission based on liquid crystal tunable filter with high signal-to-noise ratio. Sci. Rep. 14, 23655 (2024).

Zhang, Y. et al. Circularly polarized terahertz wave independently controlled tunable spin-decoupled metasurface. Results Phys. 56, 107287 (2024).

Lü, Y., Xia, J., Zhang, J., Fu, X. & Liu, H. Orthogonally polarized dual-wavelength Nd:YAlO3 laser at 1341 and 1339 nm and sum-frequency mixing for an emission at 670 nm. Appl. Opt. 53, 5141–5146 (2014).

Lü, Y., Zhang, J., Xia, J. & Liu, H. Diode-pumped quasi-three-level Nd:YVO4 laser with orthogonally polarized emission. IEEE Photon. Technol. Lett. 26, 656–659 (2014).

Wang, S., Li, C., Li, Y. & Xia, J. Orthogonally polarized dual-wavelength Nd:LiYF4 laser at 903 and 908 nm on 4F3/2 → 4I9/2 transition. Opt. Laser Technol. 180, 111510 (2025).

Lü, Y. et al. Diode-pumped cwNd:YAG three-level laser at 869 nm. Opt. Lett. 35, 3670–3672 (2010).

Lü, Y. et al. Quasi-three-level neodymium-doped yttrium aluminum garnet laser emitting at 885 nm. Opt. Lett. 37, 3177–3179 (2012).

Chen, T. et al. Tunable three-level Nd:YAG CW laser with three lowest wavelengths at 869, 875, and 878 nm. Infrared Phys. Technol. 106, 103142 (2020).

Pan, Y. et al. Polarized spectral properties and laser operation of Nd:SrAl12O19 crystal. J. Lumin. 235, 118034 (2021).

Pan, Y. et al. Growth, spectral properties, and diode-pumped laser operation of a Nd3+-doped LaMgAl11O19 crystal. Appl. Opt. 57, 9657–9661 (2018).

Huber, G., Krühler, W., Bludau, W. & Danielmeyer, H. Anisotropy in the laser performance of NdP5O14. J. Appl. Phys. 46, 3580 (1975).

Yu, H. et al. High-power dual-wavelength laser with disordered Nd:CNGG crystals. Opt. Lett. 34, 151–153 (2009).

Abernathy, G. et al. Study of all-group-IV SiGeSn mid-IR lasers with dual wavelength emission. Sci Rep 13, 18515 (2023).

Xia, J., Lü, Y., Liu, H. & Pu, Xi. Diode-pumped Pr3+:LiYF4 visible dual-wavelength laser. Opt. Commun. 334, 160–163 (2015).

Shayeganrad, G. & Mashhadi, L. Dual-wavelength CW diode-end-pumped a-cut Nd:YVO4 laser at 1064.5 and 1085.5 nm. Appl. Phys. B 111, 189 (2013).

Chen, Y. cw dual-wavelength operation of a diode-end-pumped Nd:YVO4 laser. Opt. Express Appl. Phys. B 70, 475–478 (2000).

Wei, L. et al. A passively Q-switched YVO4 Raman laser with orthogonally polarized emission at 1175.4 nm and 1165.2 nm. Laser Phys. Lett. 15, 125001 (2018).

Shayeganrad, G., Huang, Y. & Mashhadi, L. Tunable single and multiwavelength continuous-wave c-cut Nd:YVO4 laser. Appl. Phys. B 108, 67 (2012).

Wang, X. et al. Power-ratio tunable dual-wavelength laser using linearly variable Fabry–Perot filter as output coupler. Appl. Opt. 55, 879 (2016).

Huang, Y., Cho, C., Huang, Y. & Chen, Y. Orthogonally polarized dual-wavelength Nd:LuVO4 laser at 1086 nm and 1089 nm. Opt. Express 20, 5644–5651 (2012).

Chu, C., Li, Y., Chen, C., Feng, H. & Guo, H. Quasi-three-level continuous wave Nd:Na2La4(WO4)7 lasers at 0.9 μm. Results Phys. 65, 107984 (2024).

Waritanant, T. & Major, A. Diode-pumped Nd:YVO4 laser with discrete multi-wavelength tunability and high efficiency. Opt. Lett. 42, 1149–1152 (2017).

Akbari, R., Loiko, P., Xu, J., Xu, X. & Major, A. Dual-wavelength Nd:CALGO laser based on differential loss of birefringent filter. Laser Phys. Lett. 21, 015001 (2024).

Huang, Y. et al. Efficient dual-wavelength diode-end-pumped laser with a diffusion-bonded Nd:YVO4/Nd:GdVO4 crystal. Opt. Mater. Express 5, 2136 (2015).

Liang, H., Huang, T., Chang, F., Sung, C. & Chen, Y. Flexibly controlling the power ratio of dual-wavelength SESAM based mode-locked lasers with wedged-bonded Nd:YVO4/Nd:GdVO4 crystals. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Quantum Electron. 24, 1–5 (2018).

Nadimi, M., Onyenekwu, C. & Major, A. Continuous-wave dual-wavelength operation of the in-band diode-pumped Nd:GdVO4/Nd:YVO4 composite laser with controllable spectral power ratio Appl. Phys. B 126, 75 (2020).

Judd, B. Optical absorption intensities of rare-earth ions. Phys. Rev. 127, 750–761 (1962).

Carnall, W., Fields, P. & Rajnak, K. Energy levels in the trivalent lanthanide aqua ions. I. Pr3+, Nd3+, Pm3+, Sm3+, Dy3+, Ho3+, Er3+, and Tm3+. J. Chem. Phys. 49, 4424–4442 (1968).

Kaminskii, A. et al. Spectroscopy of a new laser garnet Lu3Sc2Ga3O12:Nd3+ Intensity luminescence characteristics, stimulated emission, and full set of squared reduced-matrix for Nd3+ ions |<‖U(t)‖>|2. Phys. Status Solidi 141, 471–494 (1994).

Koechner, W. Solid-state Laser Engineering (Springer, 2006).

Lünstedt, K., Pavel, N., Petermann, K. & Huber, G. Continuous-wave simultaneous dual-wavelength operation at 912 and 1063 nm in Nd:GdVO4. Appl. Phys. B 86, 65–70 (2007).

Siegman, A. & Townsend, S. Output beam propagation and beam quality from a multimode stable-cavity laser. IEEE J. Quantum Electron. 29, 1261 (1993).

Innocenzi, M., Yura, H., Fincher, C. & Fields, R. Thermal modeling of continuous-wave end-pumped solid-state lasers. Appl. Phys. Lett. 56, 1831 (1990).

Sato, Y., & Taira, T., Thermo-optical and -mechanical parameters of Nd:GdVO4 and Nd:YVO4. In 2007 Quantum Electronics and Laser Science Conference, Baltimore, MD, USA, 1–2 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1109/QELS.2007.4431478

Mukhopadhyay, P. et al. Experimental determination of the thermo-optic coefficient (dn/dT) and the effective stimulated emission cross-section (σe) of an a-axis cut 1.-at.% doped Nd:GdVO4. Appl. Phys. B 77, 81–87 (2003).

Funding

This work has been supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 62075018) and the Natural Science Foundation of Jilin Province, China (Grant No. 20220101034JC).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Chu Chu designed experiments and theoretical analyses. Shang Wang processed the data curation. Changli Li revised and approved the final manuscript. Yongliang Li performed the laser experiment.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chu, C., Yang, X., Wang, S. et al. Orthogonally polarized dual-wavelength operation at 898 and 904 nm with tunable power ratio in Nd:SA/Nd:LMA crystals. Sci Rep 15, 11293 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96378-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96378-9