Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a widespread impact on sleep quality, yet little is known about the prevalence of sleep disturbance and its impact on self-management of chronic conditions during the ongoing pandemic. To evaluate trajectories of sleep disturbance and their associations with one’s capacity to self-manage chronic conditions. A longitudinal cohort study linked to 3 active clinical trials and 2 cohort studies with 5 time points of sleep data collection (July 15, 2020–May 23, 2022). Adults living with chronic conditions who completed sleep questionnaires for two or more time points. Trajectories of self-reported sleep disturbance across 5 time points. Three self-reported measures of self-management capacity, including subjective cognitive decline, medication adherence, and self-efficacy for managing chronic disease. Five hundred and forty-nine adults aged 23 to 91 years were included in the analysis. Two-thirds had 3 or more chronic conditions; 42.4% of participants followed a trajectory of moderate or high likelihood of persistent sleep disturbance across the study period. Moderate or high likelihood of sleep disturbance was associated with age < 60 (RR 1.57, 95% CI 1.09, 2.26, P = 0.016), persistent stress (RR 1.54, 95% CI 1.16, 2.06, P = 0.003), poorer physical function (RR 1.57, 95% CI 1.17, 2.13, P = 0.003), greater anxiety (RR 1.40, 95% CI 1.04, 1.87, P = 0.03) and depression (RR 1.63, 95% CI 1.20, 2.22, P = 0.002). Moderate or high likelihood of sleep disturbance was also independently associated with subjective cognitive decline, poorer medication adherence, and worse self-efficacy for managing chronic diseases (all P < 0.001). Persistent sleep disturbance during the pandemic may be an important risk factor for inadequate chronic disease self-management and potentially poor health outcomes in adults living with chronic conditions. Public health and health system strategies might consider monitoring sleep quality in adults with chronic conditions to optimize health outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic led to unprecedented disruptions to nearly every facet of daily life, with direct and indirect impacts on adults with chronic conditions. In addition to being at increased risk of severe illness from COVID-19,1 social distancing recommendations, economic hardships, and changes in healthcare access have created new challenges for these individuals in terms of effectively participating in the management of their own health.2,3,4,5,6 Beyond the direct effects of COVID-19, studies have suggested that the pandemic has made it more difficult to engage in requisite self-care behaviors, such as maintaining a healthy lifestyle and taking prescribed medication.7,8 This may be the result of many factors, including more infrequent engagement with healthcare professionals and care teams, disruptions in daily routine, increased social isolation, loneliness and/or stress resulting in depression and anxiety, as well as subsequent cognitive symptoms including difficulties in memory, attention, and information processing that can readily affect one’s health literacy skills and treatment adherence.9,10

Changes in sleep quality might also have formidable consequences to an adult’s capacity to self-manage chronic conditions. Early in the pandemic, a significant increase in sleep disturbance was reported among older adults with chronic conditions,11 colloquially labeled as the “coronasomnia” phenomenon.12 Disturbed sleep has previously been associated with reduced self-management behaviors, missed medical appointments, and worse chronic disease outcomes.13,14 Yet, little is known about how sleep quality changed during the pandemic in adults living with chronic conditions and whether certain sleep trajectories have affected their ability to effectively manage their health.

Leveraging an ongoing, NIH-sponsored COVID-19 & Chronic Conditions (C3) study, we assessed the prevalence of persistent sleep disturbance across the first two years of the pandemic and sought to investigate whether prolonged disturbed sleep was associated with a compromised capacity to self-manage chronic conditions. As a longitudinal cohort study, adults living with one or multiple chronic conditions have been interviewed 8 times to date since the beginning of the pandemic, of which sleep quality was examined at 5 of these assessments. We specifically sought to examine trajectories of sleep disturbance between July 2020 and May 2022, and to investigate associations between sleep disturbance trajectories and self-management capacity. Findings from this study may help reveal those individuals at greater risk of experiencing persistent sleep disturbance, and further inform future public health or health system strategies for screening and intervention to optimize health outcomes.

Results

Study sample characteristics and sleep disturbance trajectories

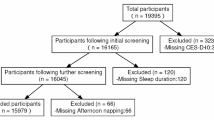

Among the 549 participants with sleep measures obtained at two or more time points between July 15, 2020, and May 23, 2022, ages ranged from 23 to 91 years (mean [SD]: 63 [11]). Nearly two-thirds were women, and self-identified race and ethnic distribution included 45.2% White, 29.3% Black, and 20.6% Hispanic/Latino (Table 1). Participants included in this study were not significantly different from those excluded (N = 123) regarding age, sex, race, ethnicity, income, education, health literacy, or the number of chronic conditions (Supplement Table S3).

Using a PROMIS Sleep Disturbance (PROMIS-SD) T-score threshold of > 55 to define sleep disturbance at each time point, we identified three distinct sleep disturbance trajectories (Fig. 1):

-

1.

Low sleep disturbance (57.6%) – Participants with a consistently low likelihood of experiencing sleep disturbance throughout the study period.

-

2.

Moderate Sleep Disturbance (33.9%) – Participants with a moderate likelihood of sleep disturbance that persisted across waves.

-

3.

High Sleep Disturbance (8.6%) – Participants who began with a high likelihood of sleep disturbance, which worsened over time, reaching nearly 100% likelihood by the end of the study.

Factors associated with sleep disturbance trajectories

In bivariate analyses, age < 60 years, Hispanic/Latino ethnicity, living below the poverty level, persistent moderate-to-high stress, persistently low physical function, and persistent symptoms of depression and anxiety were associated with a high sleep disturbance trajectory (Table 1). In multivariable analyses, age < 60 (adjusted risk ratio (aRR) [95% CI], 1.57 [1.09, 2.26]; P = 0.016) and persistent stress (1.54 [1.16, 2.06]; P = 0.003), persistently low physical function (1.57 [1.17, 2.13]; P = 0.003), anxiety (1.40 [1.04, 1.87]; P = 0.03), and depression (1.63 [1.20, 2.22]; P = 0.002) were significantly associated with a moderate or high sleep disturbance trajectory (Table 2).

Sleep disturbance trajectories and self-management outcomes

A high likelihood of sleep disturbance was associated with subjective cognitive decline (ECog score mean [SD], 1.7 [0.6] vs. low sleep disturbance, 1.3 [0.36]; P < 0.001), poorer medication adherence (ASK-12 score, 25.3 [6.8] vs. 19.3 [5.4]; P < 0.001), and lower self-efficacy for managing chronic diseases (Lorig score, 6.1 [2.6] vs. 8.2 [1.8]; P < 0.001) (Table 1). In multivariable analyses (Table 3), participants categorized to a moderate or high likelihood of sleep disturbance demonstrated greater subjective cognitive decline (ECog least square means (LSM) [95% CI], 1.51 [1.44, 1.59] vs. 1.32 [1.25, 1.39]; P < 0.001), poorer medication adherence (ASK-12, 22.2 [21.3, 23.2] vs. 19.8 [19.0, 20.7]; P < 0.001), and lower self-efficacy for managing chronic diseases (Lorig, 7.0 [6.67, 7.33] vs. 7.81 [7.51, 8.11], P < 0.001), compared to those following a low sleep disturbance trajectory.

In addition, older age (≥ 70 years) was associated with subjective cognitive decline (ECog LSM [95% CI], 1.48 [1.38, 1.58] vs. 1.35 [1.26, 1.44] for < 60 years; P = 0.002), while Hispanic/Latino ethnicity was associated with poorer medication adherence (ASK-12, 22.2 [20.8, 23.6] vs. 19.5 [18.5, 20.5] for non-Hispanic/Latino White; P = 0.001) and living below poverty level was associated with both subjective cognitive decline (ECog, 1.49 [1.40, 1.58] vs. 1.35 [1.28, 1.41]; P = 0.009) and lower self-efficacy (Lorig, 7.02 [6.62, 7.42] vs. 7.79 [7.51, 8.07]; P = 0.001) (Table 3). Associations between sleep disturbance trajectories and self-management outcomes remained significant after further adjusting for physical and mental health indicators, suggesting that the relationships between sleep disturbance and self-management abilities persist beyond these confounding effects. (Supplement Tables S4–S6).

Sensitivity analysis

A sensitivity analysis using an alternative PROMIS-SD T-score threshold of > 45 (i.e., equivalent to Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) > 5) identified three alternative sleep disturbance trajectories (Supplement Fig. S1). Nearly two-thirds of the participants (63.5%) were categorized as having a high likelihood of persistent sleep disturbance throughout the pandemic, while 26.8% were identified as initially having a moderate likelihood of sleep disturbance, which worsened during the second COVID-19 surge then gradually improved by the end of the study period. A few participants (9.7%) were categorized to the third trajectory where they began with a low likelihood of sleep disturbance, experienced further improvement in 2021, and saw a slight worsening after the Omicron surge. The results from this sensitivity analysis were consistent with those from the main analysis using a PROMIS-SD T-score threshold of > 55, demonstrating the association between a persistently high sleep disturbance likelihood and poorer self-management abilities (data not shown).

Discussion

In this sample of U.S. adults living with chronic conditions surveyed throughout the early years of the pandemic, we identified three distinct trajectories of sleep disturbance. While over half of the participants maintained a low likelihood of experiencing persistent poor sleep, nearly half exhibited a moderate to high likelihood of sleep disturbance. Those who were younger and in persistently poor physical and mental health were more likely to experience sleep disturbance, which, in turn, was associated with worse cognitive concerns and poorer self-management abilities, including inadequate medication adherence.

Self-management abilities are essential for any adult living with chronic conditions. Those who struggle to adequately self-manage their health may be more vulnerable to adverse health outcomes during public health crises, such as COVID-19, when access to healthcare professionals, family/community support, and healthcare resources is disrupted or inconsistent.4,6,15 Poor self-management of chronic conditions was reported even among patients who adapted to restructured healthcare services,16 which likely contributed to an estimated 44,600 excess non-COVID-19 deaths in the U.S. between March and August 2020, with the leading causes being diabetes, dementia, and heart disease.17 These early pandemic data highlight the critical need to identify and support individuals at risk of inadequate self-management to minimize the downstream consequences of chronic care disruptions during public health emergencies.

Leveraging a unique longitudinal dataset spanning two years of the pandemic, this study identifies persistent sleep disturbance as a risk factor for poorer self-management abilities. Several mechanisms may explain this relationship. First, sleep disturbance negatively affects cognitive performance, particularly executive functioning,18,19,20,21,22,23 which is essential for complex daily self-management tasks such as monitoring symptoms, managing diet and physical activity, adhering to medication regimens, and engaging with healthcare professionals. Although we did not include objective cognitive assessments, participants with a moderate or high likelihood of persistent sleep disturbance reported greater subjective cognitive decline than those with a low likelihood of sleep disturbance. Second, sleep disturbance may reduce motivation to engage in health-promoting behaviors and lower confidence in one’s ability to manage chronic health conditions.24,25,26.

Additionally, our findings align with prior research showing that younger adults were more likely to experience sleep disturbance,27 likely due to the pandemic’s disproportionate burden on middle-aged adults balancing financial, work, and caregiving responsibilities while managing their own chronic conditions. The pandemic introduced unprecedented stressors, such as school closures, job loss, and economic instability, which may have disrupted sleep patterns and further impaired self-management abilities. As pandemic-related restrictions have been lifted and a new post-pandemic “normal” has emerged,28 ongoing longitudinal investigations of sleep health and self-management abilities remain essential. Understanding the long-term impact of pandemic-related disruptions is critical for future public health preparedness and ensuring effective chronic disease management during and after public health crises.

Beyond individual characteristics, our findings highlight structural inequities in self-management abilities. Hispanic/Latino adults reported poorer medication adherence compared to their White counterparts, and individuals living below the poverty level demonstrated greater subjective cognitive decline and lower self-efficacy. The COVID-19 pandemic disproportionately affected chronic disease management in socioeconomically disadvantaged populations, widening health disparities.5 Public health and health system interventions should prioritize extending self-management support to historically marginalized individuals and communities to mitigate pandemic-exacerbated health inequities.

This research has several limitations. Foremost, as participants were drawn from ongoing research projects focused on adults with at least one chronic condition in a single metropolitan area, findings may not be generalizable to other populations, particularly younger, healthier individuals. Second, sleep data were not collected in earlier waves of the C3 study or as part of the parent studies, limiting comparisons to pre-pandemic sleep quality. Third, objective measures of sleep, cognition, or physical function were not collected in this survey-based study. Fourth, participant attrition in later survey waves may introduce bias. However, over 85% of participants who provided initial sleep data remained in the study across four waves, and those excluded from the analysis did not significantly differ from the analyzed sample. The strengths of this study include: (1) longitudinal examination of higher-risk adults who are under-represented in the existing literature yet are among the most vulnerable to the ongoing effects of the pandemic; (2) a socioeconomically and racially/ethnically diverse sample; and (3) detailed measures of self-management abilities using validated instruments.

Conclusions

Persistent sleep disturbance during two years of the COVID-19 pandemic was associated with poorer self-management abilities in adults with chronic conditions. Health inequity in self-management during the pandemic was apparent. Public health and health system interventions should prioritize integrating sleep health into chronic disease management, particularly in socioeconomically disadvantaged populations, to promote resilience against future public health emergencies and reduce morbidity and mortality associated with inadequate self-care.

Methods

This study follows the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guidelines. The study was approved by the Northwestern University Institutional Review Board (STU00201639, STU00203777, STU00201640, STU00204465, and STU00026255), and all research was performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Study design

The C3 study is an ongoing, telephone-based survey that began at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in the U.S. among adults with chronic conditions. The initial survey was conducted from March 13 to 20, 2020, during the first week of the outbreak in Chicago, Illinois. Over two years, from March 27, 2020, to May 23, 2022, seven additional study interviews, referred to as waves, were conducted (See Supplement Table S1).

Study participants

Participants were recruited from five ongoing National Institutes of Health (NIH)-funded health services research projects conducted across seven primary care sites in the greater Chicago area, including five academic internal medicine clinics and two federally qualified health centers. The five parent studies included:

-

1.

Health Literacy and Cognitive Function Among Older Adults (“LitCog”; R01AG030611) – A cohort study examining cognitive and psychosocial factors associated with self-management and chronic disease outcomes over time among older adults (ages 55–74 at baseline interview conducted between 2008 and 2015)

-

2.

Self-Management Behaviors among Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) Patients with Multi-morbidity (“COPD”; R01HL126508) – A cohort study investigating cognitive and psychosocial factors associated with self-management behaviors among patients with COPD and multi-morbidity.

-

3.

Electronic Health Records-Based Universal Medication Schedule to Improve Adherence to Complex Regimens (“Remind”; R01NR015444) – A randomized controlled trial (RCT) evaluating health system strategies leveraging electronic health records and consumer technologies to enhance adherence to complex medication regimens

-

4.

A Universal Medication Schedule to Promote Adherence to Complex Drug Regimens (“Portal”; R01AG046352) – An RCT evaluating the impact of a standardized medication schedule on adherence and patient safety.

-

5.

Transplant Regimen Adherence for Kidney Recipients by Engaging Information Technologies: The TAKE IT Trial (“TakeIT”; R01DK110172) – An RCT assessing a technology-enabled strategy to promote medication adherence among kidney transplant recipients and mobilize resources to manage inadequate adherence.

These studies were selected because they primarily enroll middle-aged or older adults (ages 23–88 years) with one or more chronic conditions, making them more vulnerable to severe COVID-19 infection and its complications. They also use common assessments, enabling uniform measurement of key patient characteristics.29,30,31,32

Recruitment and data collection

All parent studies excluded individuals with severe hearing, vision, or cognitive impairments. Four studies enrolled only English-speaking participants, while one study included both English- and Spanish-speaking participants.

Trained research staff recruited participants from these parent studies to participate in a telephone survey pertaining to COVID-19. Informed consent was obtained from all participants. Survey data were collected using REDCap, with each interview lasting 20–40 min. Participants received a $10 – $15 gift card as compensation.

A total of 672 participants completed the Wave 1 interview. Follow-up cooperation rates remained high, ranging from 72 to 93%. To examine sleep trajectories during the COVID-19 pandemic, we excluded 123 participants due to missing sleep data between Waves 4 and 8, resulting in a final analytic sample of 549 participants who provided sleep data from at least two waves (See Supplement Table S2).

Exposure: assessment of sleep disturbance trajectories

From Waves 4 through 8, self-reported sleep quality was measured using the Patient-Reported Outcomes Information System 4-item short-form battery for sleep disturbance (PROMIS-SD). This tool evaluates perceived difficulties and concerns with falling asleep, staying asleep, and the adequacy of sleep, with higher scores indicating poorer sleep quality. Sleep disturbance was conservatively defined as a PROMIS-SD T-score > 55, based on the developer-recommended threshold of 0.5 standard deviations above the population mean.33,34.

To identify distinct sleep disturbance trajectories, we applied a group-based trajectory modeling approach using the traj command in Stata/SE, version 15 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, US).35 This method estimates discrete mixture models on longitudinal data—assuming a Bernoulli distribution (logistic model) for the dichotomous sleep disturbance variable—and assigns individuals into trajectory groups based on their likelihood of belonging to a specific group. The Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) was used to determine the optimal number of discrete trajectories. Participants were assigned to a trajectory based on posterior probabilities.36

The PROMIS-SD T-score has been validated against the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI)37, a widely used measure of sleep quality, with a publicly available conversion table.38 Although both tools measure a similar construct of sleep quality, as supported by a convergent validity of 0.83, PROMIS-SD has demonstrated greater measurement precision than PSQI despite having fewer total items.39 Notably, a PROMIS-SD T-score > 55 corresponds to a PSQI score > 10, while the commonly used PSQI cutoff for sleep disturbance is > 5, equivalent to PROMIS-SD T-score > 45.38,40,41,42,43,44 In our previous cross-sectional analysis of Wave 5 data, applying different cutoffs significantly impacted the proportion of participants categorized as having sleep disturbance: lowering the PROMIS-SD T-score cutoff from > 55 to > 45 increased the prevalence of sleep disturbance from 20.4 to 71.2%.45 Therefore, we conducted a sensitivity analysis using a PROMIS-SD T-score > 45 to define sleep disturbance, facilitating comparison with other studies.

Outcomes: assessment of self-management ability

The primary outcomes of interest were measures of self-management, using the latest available data (i.e., Wave 8) for each participant.

-

1.

Subjective cognitive decline was measured using a subset of items from the Everyday Cognition (ECog) scale, a validated, self-reported measure of cognitive functioning.46,47 ECog scores range from 1 to 4, with higher scores indicating worse cognitive abilities.46

-

2.

Medication adherence was measured using the Adherence Starts with Knowledge 12 (ASK-12) survey.48 ASK-12 scores range from 12 to 60, with higher scores indicating poorer adherence.49 This tool has demonstrated good internal consistency reliability (α = 0.75) and test–retest reliability (intraclass correlation 0.79). Convergent validity has also been established through pharmacy claims data.49

-

3.

Self-efficacy was measured using Lorig’s Self-Efficacy for Managing Chronic Disease 6-item Scale, which assesses multiple domains of chronic disease self-management, including symptom control, role function, emotional functioning, and communication with clinicians. Scores range from 1 to 10, with lower scores indicating lower self-efficacy.50

Covariates: demographic characteristics, physical and mental health

Across all five NIH parent studies, participant demographics (age, sex, race and ethnicity), socioeconomic status (household income, educational attainment), and self-reported chronic conditions were uniformly collected. Each parent study also included a measure of health literacy, categorizing participants as having low, marginal, or adequate health literacy, as previously described in detail.29 All demographic covariates were collected during the baseline interview.

The Cohen 10-item Perceived Stress Scale (PSS), adapted to assess perceived stress related to COVID-19, was used to measure stress perception from Waves 4 through 8.51 Mental health was evaluated from Waves 3 through 8 using the PROMIS short-form batteries for depression and anxiety, with clinically significant symptoms defined as a T-score > 55.34,52 Physical health was assessed at Waves 5 and 7 using the PROMIS 10-item short-form battery for physical function, with low physical function defined as a T-score < 45.33,34,53,54 The earliest and latest available data points participants had for PROMIS physical function, depression, anxiety, and PSS were used to define the presence or absence of persistently low physical function, persistent depression, persistent anxiety, and persistent stress, respectively, thereby accounting for the potential confounding effects of physical and mental health indicators.

Statistical analysis

We completed a series of analyses to examine (1) which participant characteristics were associated with distinct trajectories of sleep disturbance (“sleep trajectories”) and (2) whether sleep trajectories were subsequently associated with measures of self-management ability.

Descriptive and bivariate analyses

First, descriptive statistics (mean with standard deviation for continuous variables and percentage frequencies for categorical variables) were calculated for all participant characteristics and survey responses. Associations between sleep trajectories and participant characteristics as well as outcome measures were examined in bivariate analyses using chi-square tests, t-tests, or one-way ANOVA tests, as appropriate.

Multivariable analysis of sleep trajectories

To estimate relative risks (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of following a particular sleep trajectory, we used multivariable Poisson regression models.55 All multivariable models included sex, parent study, and variables that were significantly associated with sleep trajectories in bivariate analyses. Given the potential overlap between related constructs (i.e., physical and mental health) and concern for overadjustment, each model included only one measure of physical or mental health that was significantly associated with sleep trajectories in the bivariate analyses.

Multivariable analysis of self-management outcomes

For self-management outcome measures significantly associated with sleep trajectories in bivariate analyses, we used multiple linear regression models to estimate least square means (LSM) with 95% CIs. LSM provide adjusted predicted values for each outcome at specific levels of the independent variables, enabling a more intuitive interpretation than beta coefficients, particularly for categorical independent variables. All models adjusted for a priori covariates of sex, parent study, age, race and ethnicity, poverty status, and educational attainment based on their established associations with self-management abilities.47,56 Because physical and mental health may be associated with both sleep disturbance and self-management, we conducted sensitivity analyses by separately adjusting for physical function and mental health indicators to assess their potential confounding effects.

Sensitivity analyses

We compared the baseline characteristics of C3 study participants included in this analysis with those who were excluded. We conducted additional sensitivity analyses using an alternative PROMIS-SD T-score threshold (> 45) to define sleep disturbance, as described in the Exposure: Assessment of sleep disturbance trajectories section

All analyses were performed using Stata/SE, version 15 (StataCorp).35 Statistical significance was defined as two-sided P < 0.05.

Data availability

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Yang, J. et al. Prevalence of comorbidities and its effects in patients infected with SARS-CoV-2: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Infect. Dis.: IJID: Off. Publ. Int. Soci. Infect. Dis. 94, 91–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2020.03.017 (2020).

Nicola, M. et al. The socio-economic implications of the coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19): A review. Int. J. Surg. 78, 185–193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.04.018 (2020).

Czeisler, M. E. et al. Delay or Avoidance of Medical Care Because of COVID-19-Related Concerns - United States, June 2020. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly Rep. 69, 1250–1257. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6936a4 (2020).

Wright, A., Salazar, A., Mirica, M., Volk, L. A. & Schiff, G. D. The invisible epidemic: Neglected chronic disease management during COVID-19. J Gen Intern Med 35, 2816–2817. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-020-06025-4 (2020).

Mobula, L. M., Heller, D. J., Commodore-Mensah, Y., Walker Harris, V. & Cooper, L. A. Protecting the vulnerable during COVID-19: Treating and preventing chronic disease disparities. Gates Open Res 4, 125. https://doi.org/10.12688/gatesopenres.13181.1 (2020).

Beran, D. et al. Beyond the virus: Ensuring continuity of care for people with diabetes during COVID-19. Prim Care Diabetes 15, 16–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pcd.2020.05.014 (2021).

Santos, B. et al. Patient-perceived impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on medication adherence and access to care for long-term diseases: A cross-sectional online survey. COVID 4, 191–207. https://doi.org/10.3390/covid4020015 (2024).

Ruksakulpiwat, S., Zhou, W., Niyomyart, A., Wang, T. & Kudlowitz, A. How does the COVID-19 pandemic impact medication adherence of patients with chronic disease?: A systematic review. Chronic Illn. 19, 495–513. https://doi.org/10.1177/17423953221110151 (2023).

Penninx, B. W. J. H., Benros, M. E., Klein, R. S. & Vinkers, C. H. How COVID-19 shaped mental health: from infection to pandemic effects. Nat. Med. 28, 2027–2037. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-022-02028-2 (2022).

Vasan, S., Eikelis, N., Lim, M. H. & Lambert, E. Evaluating the impact of loneliness and social isolation on health literacy and health-related factors in young adults. Front. Psychol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.996611 (2023).

Wong, S. Y. S. et al. Impact of COVID-19 on loneliness, mental health, and health service utilisation: A prospective cohort study of older adults with multimorbidity in primary care. Br J Gen Pract 70, e817–e824. https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp20X713021 (2020).

Gupta, R. & Pandi-Perumal, S. R. COVID-Somnia: How the pandemic affects sleep/wake regulation and how to deal with it?. Sleep Vigil 4, 51–53. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41782-020-00118-0 (2020).

Zhu, B. et al. Relationship between sleep disturbance and self-care in adults with type 2 diabetes. Acta Diabetol 55, 963–970. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00592-018-1181-4 (2018).

Chasens, E. R., Korytkowski, M., Sereika, S. M. & Burke, L. E. Effect of poor sleep quality and excessive daytime sleepiness on factors associated with diabetes self-management. Diabet. Educ. 39, 74–82. https://doi.org/10.1177/0145721712467683 (2013).

Chudasama, Y. V. et al. Impact of COVID-19 on routine care for chronic diseases: A global survey of views from healthcare professionals. Diabet. Metab. Syndr. 14, 965–967. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsx.2020.06.042 (2020).

Sumner, J. et al. Continuing chronic care services during a pandemic: results of a mixed-method study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 22, 1009. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-022-08380-w (2022).

Shiels, M. S. et al. Impact of population growth and aging on estimates of Excess U.S. deaths during the COVID-19 pandemic, march to august 2020. Ann. Intern. Med. 174, 437–443. https://doi.org/10.7326/M20-7385 (2021).

Ji, X. & Fu, Y. The role of sleep disturbances in cognitive function and depressive symptoms among community-dwelling elderly with sleep complaints. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiat. 36, 96–105. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.5401 (2021).

Walker, M. P. The role of sleep in cognition and emotion. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1156, 168–197. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04416.x (2009).

Okuda, M. et al. Effects of long sleep time and irregular sleep-wake rhythm on cognitive function in older people. Sci. Rep. 11, 7039. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-85817-y (2021).

Blackwell, T. et al. Association of sleep characteristics and cognition in older community-dwelling men: the MrOS sleep study. Sleep 34, 1347–1356. https://doi.org/10.5665/SLEEP.1276 (2011).

Spira, A. P. et al. Actigraphic sleep duration and fragmentation in older women: Associations with performance across cognitive domains. Sleep https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/zsx073 (2017).

Walsh, C. M. et al. Weaker circadian activity rhythms are associated with poorer executive function in older women. Sleep 37, 2009–2016. https://doi.org/10.5665/sleep.4260 (2014).

Massar, S. A. A., Lim, J. & Huettel, S. A. Sleep deprivation, effort allocation and performance. Prog. Brain Res. 246, 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.pbr.2019.03.007 (2019).

Ritland, B. M. et al. Effects of sleep extension on cognitive/motor performance and motivation in military tactical athletes. Sleep Med. 58, 48–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2019.03.013 (2019).

Simoes Maria, M. et al. Sleep characteristics and self-rated health in older persons. Eur Geriatr Med 11, 131–138. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41999-019-00262-5 (2020).

Hisler, G. C. & Twenge, J. M. Sleep characteristics of US adults before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Social Sci Med 276, 113849. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.113849 (2021).

(CDC), C. f. D. C. a. P. CDC Museum COVID-19 Timeline, https://www.cdc.gov/museum/timeline/covid19.html (2023).

O’Conor, R. et al. Knowledge and behaviors of adults with underlying health conditions during the onset of the COVID-19 U.S. outbreak: The Chicago COVID-19 comorbidities survey. J. Commun. Health 45, 1149–1157. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-020-00906-9 (2020).

Wolf, M. S. et al. Awareness, attitudes, and actions related to COVID-19 among adults with chronic conditions at the onset of the U.S. Outbreak: A cross-sectional survey. Ann Intern Med 173, 100–109. https://doi.org/10.7326/M20-1239 (2020).

Bailey, S. C. et al. Changes in COVID-19 knowledge, beliefs, behaviors, and preparedness among high-risk adults from the onset to the acceleration phase of the US outbreak. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 35, 3285–3292. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-020-05980-2 (2020).

Opsasnick, L. A. et al. Trajectories of perceived susceptibility to COVID-19 over a year: the COVID-19 & chronic conditions (C3) cohort study. Medicine (Baltimore) 101, e29376. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000029376 (2022).

Cella, D. et al. The patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS) developed and tested its first wave of adult self-reported health outcome item banks: 2005–2008. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 63, 1179–1194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.04.011 (2010).

HealthMeasures. PROMIS Score Cut Points, https://www.healthmeasures.net/index.php?option=com_content&view=category&layout=blog&id=200&Itemid=1213

Jones, B. L. & Nagin, D. S. A note on a stata plugin for estimating group-based trajectory models. Sociol. Method Res. 42, 608–613. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124113503141 (2013).

Jones, B. L., Nagin, D. S. & Roeder, K. A SAS procedure based on mixture models for estimating developmental trajectories. Sociol. Methods Res. 29, 374–393. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124101029003005 (2001).

Buysse, D. J., Reynolds, C. F. 3rd., Monk, T. H., Berman, S. R. & Kupfer, D. J. The Pittsburgh sleep quality index: A new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res 28, 193–213. https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4 (1989).

Cella, D. et al. PROsetta Stone analysis report: A rosetta stone for patient reported outcomes. Volume 2. (Department of Medical Social Sciences, Feinbeg School of Medicine, Northwestern University, Chicago, IL, 2016).

Yu, L. et al. Development of short forms from the PROMIS sleep disturbance and Sleep-Related Impairment item banks. Behav. Sleep Med. 10, 6–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/15402002.2012.636266 (2011).

Huang, Y. & Zhao, N. Generalized anxiety disorder, depressive symptoms and sleep quality during COVID-19 outbreak in China: A web-based cross-sectional survey. Psychiatry Res. 288, 112954. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112954 (2020).

Zhao, X., Lan, M., Li, H. & Yang, J. Perceived stress and sleep quality among the non-diseased general public in China during the 2019 coronavirus disease: A moderated mediation model. Sleep Med 77, 339–345. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2020.05.021 (2021).

Casagrande, M., Favieri, F., Tambelli, R. & Forte, G. The enemy who sealed the world: Effects quarantine due to the COVID-19 on sleep quality, anxiety, and psychological distress in the Italian population. Sleep Med. 75, 12–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2020.05.011 (2020).

Cellini, N., Canale, N., Mioni, G. & Costa, S. Changes in sleep pattern, sense of time and digital media use during COVID-19 lockdown in Italy. J. Sleep Res. 29, e13074. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsr.13074 (2020).

Zheng, C. et al. COVID-19 pandemic brings a sedentary lifestyle in young adults: A cross-sectional and longitudinal study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17176035 (2020).

Kim, M. et al. Prevalence and risk factors of sleep disturbance in adults with underlying health conditions during the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. Medicine (Baltimore) 101, e30637. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000030637 (2022).

Tomaszewski Farias, S. et al. The measurement of everyday cognition: development and validation of a short form of the Everyday Cognition scales. Alzheimers Dement 7, 593–601. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2011.02.007 (2011).

Farias, S. T. et al. The measurement of everyday cognition (ECog): scale development and psychometric properties. Neuropsychology 22, 531–544. https://doi.org/10.1037/0894-4105.22.4.531 (2008).

Matza, L. S. et al. Derivation and validation of the ASK-12 adherence barrier survey. Ann. Pharmacother. 43, 1621–1630. https://doi.org/10.1345/aph.1M174 (2009).

Matza, L. S. et al. Derivation and validation of the ASK-12 adherence barrier survey. Ann. Pharmacother. 43, 1621 (2009).

Lorig, K. R., Sobel, D. S., Ritter, P. L., Laurent, D. & Hobbs, M. Effect of a self-management program on patients with chronic disease. Eff. Clin. Pract. 4, 256–262 (2001).

Cohen, S., Kamarck, T. & Mermelstein, R. A global measure of perceived stress. J. Health Soc. Behav. 24, 385–396 (1983).

Pilkonis, P. A. et al. Item banks for measuring emotional distress from the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS(R)): Depression, anxiety, and anger. Assessment 18, 263–283. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191111411667 (2011).

Ader, D. N. Developing the patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS). Med. Care 45, S1–S2. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.mlr.0000260537.45076.74 (2007).

Rose, M. et al. The PROMIS Physical Function item bank was calibrated to a standardized metric and shown to improve measurement efficiency. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 67, 516–526. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.10.024 (2014).

Zou, G. A modified poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. Am. J. Epidemiol. 159, 702–706. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwh090 (2004).

McQuaid, E. L. & Landier, W. Cultural issues in medication adherence: Disparities and directions. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 33, 200–206. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-017-4199-3 (2018).

Acknowledgements

We thank the participants and the staff of the C3 study.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R01NR015444, R01AG030611, R01AG075043, R01AG046352, R01DK110172, R01HL126508, P01AG011412, R01HL140580, K23AG088497), with institutional support from UL1TR001422 and from the Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine (P30AG059988). The funding agency played no role in the study design, collection of data, analysis, or interpretation of data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: MK, LR, MSW. Data curation: SB, LR. Statistical analysis: LR. Funding acquisition: MSW, JAL, SCB. Investigation: MK, LR, MSW. Project administration: JYB, MB, PZ, RML, SCB, MSW. Software: LR. Writing – original draft: MK. Writing – review and editing: MK, LR, SB, JYB, MB, PZ, RML, SCB, MJK, DPL, SHYC, JAL, SW, YL, PCZ, MSW.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Dr. Kim reports grants from the NIH and Genentech, Inc. outside the submitted work. Dr. Bailey reports grants from the NIH, Merck, Pfizer, Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, Retirement Research Foundation for Aging, Lundbeck, and Eli Lilly via her institution and personal fees from Sanofi, Pfizer, University of Westminster, Lundbeck, Gilead, and Luto UK outside the submitted work. Dr. Wolf reports grants from the NIH, Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, and Eli Lilly, and personal fees from Pfizer, Sanofi, Luto UK, University of Westminster, and Lundbeck outside the submitted work. All the other authors report no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, M., Rogers, L., Batio, S. et al. Trajectories of sleep disturbance and self-management of chronic conditions during COVID-19 among middle-aged and older adults. Sci Rep 15, 12324 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96384-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96384-x