Abstract

Basalt fiber-reinforced concrete (BFRC) mixed with fly ash, combined with advanced machine learning techniques, offers a practical, cost-effective, and less time-consuming alternative to traditional experimental methods. Conventional approaches to evaluating mechanical properties, such as compressive and splitting tensile strengths, typically require sophisticated equipment, meticulous sample preparation, and extended testing periods. These methods demand substantial financial resources, specialized labor, and considerable time for data collection and analysis. The integration of machine learning provides a transformative solution by enabling accurate prediction of concrete properties with minimal experimental data. The methods of data collection from literature and analysis were used and 121 records were collected from experimentally tested basalt fiber reinforced concrete samples measuring the compressive and splitting tensile strengths of the concrete. Eleven (11) critical factors have been considered as constituents of the studied concrete to predict the Fc-Compressive strength (MPa) and Fsp-Splitting tensile strength (MPa), which are the output parameters. The collected records were divided into training set (96 records = 80%) and validation set (25 records = 20%) following the requirements for data partitioning for sustainable machine learning application. Seven (7) selected machine learning techniques are applied in the prediction. Further, performance evaluation indices were used to compare the models’ abilities and lastly, the Hoffman and Gardener’s technique was used to evaluate the sensitivity of the parameters on the concrete strengths. At the end of the exercise, results were collated. In predicting the compressive strength (Fc), AdaBoost similarly excels, matching XGBoosting’s validation performance with R2 of 0.98 and the same MAE values. This shows the effectiveness of boosting techniques for predictive modeling in concrete strength estimation. For splitting tensile strength (Fsp), AdaBoost also outperforms most models, achieving an R2 of 0.96 for training and validation phases. Its exceptionally low validation MAE of 0.124 MPa underscores its excellent generalization capabilities. Overall, XGBoosting and AdaBoost consistently demonstrate superior performance for both compressive and splitting tensile strength predictions, followed closely by KNN. These models benefit from advanced ensemble techniques that efficiently handle non-linear patterns and noise. SVR also performs admirably, whereas GEP and GMDHNN exhibit weaker predictive capabilities due to limitations in handling complex data dynamics. For the sensitivity analysis, the Hoffman and Gardener’s method of sensitivity analysis proves instrumental in identifying key drivers of strength in fiber-reinforced concrete, guiding informed decision-making for material optimization and sustainable construction practices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Background

The strength behavior of concrete mixed with industrial byproducts like fly ash has been extensively studied due to its potential to enhance mechanical properties and durability while promoting sustainability in the construction industry1,2. Fly ash, a byproduct of coal combustion, is commonly used as a partial replacement for cement in concrete mixtures3. Its pozzolanic properties contribute to the long-term strength gain of concrete by reacting with calcium hydroxide to form additional calcium silicate hydrate (C–S–H), which improves the overall microstructure4. The incorporation of fly ash enhances compressive and flexural strength, reduces permeability, and improves resistance to sulfate attacks and alkali-silica reactions. Additionally, fly ash-modified concrete exhibits lower heat of hydration, making it particularly beneficial for mass concrete applications where temperature control is critical5. In the construction industry, the use of fly ash not only leads to cost savings by reducing cement consumption but also supports environmental sustainability by repurposing industrial waste and lowering the carbon footprint of concrete production. Its ability to improve workability and durability makes it a preferred choice for infrastructure projects, high-performance concrete applications, and green building initiatives6,7,8,9. By optimizing the mix proportions, fly ash can effectively replace traditional cementitious materials while maintaining or even enhancing the performance of concrete structures.

Basalt fiber reinforced concrete mixed with fly ash is a composite material that combines the strength and durability of basalt fibers with the environmental benefits of fly ash1. Basalt fibers, derived from volcanic rocks, are known for their high tensile strength, resistance to corrosion, and thermal stability2,3,4. When added to concrete, they enhance its mechanical properties, including its tensile strength, flexural strength, and impact resistance5,6,7,8,9. Fly ash, a byproduct of coal combustion, is often used in concrete as a partial replacement for cement, contributing to sustainability by reducing the carbon footprint10,11,12,13 of the material (see Fig. 1). The combination of basalt fibers and fly ash improves the concrete’s workability, reduces cracking, and increases its long-term durability, making it suitable for various applications, including in harsh environmental conditions14,15,16,17,18,19. This mix also offers an eco-friendly solution by utilizing industrial waste and providing a more durable alternative to traditional concrete.

Concrete is essential in civil engineering, functioning as a primary construction material20,21,22,23,24. The characteristics of concrete are affected by numerous factors that must be meticulously evaluated25,26,27,28,29. These characteristics include loading conditions, construction methods, ambient conditions, and the ratios of its constituent materials1,2,3. Estimating the strength of concrete is problematic due to the complex nature of its basic components and manufacturing processes30,31,32,33. Under conditions of high strain-rate loading, fibers implanted in concrete can effectively impede the bridging process that initiates and propagates cracks2,28. Fibers enhance the strength of concrete; yet, the high ductility of flexible fibers may diminish the material’s fracture resistance3,33. Basalt fiber (BF) possesses a substantial modulus of elasticity, offering remarkable stiffness, structural integrity, and longevity4,21.

BF is acknowledged as a versatile and useful material due to its exceptional combination of properties, leading to its vast applications across several sectors34,35,36,37. The mechanical properties of BF have been assessed in cementitious composites, emphasizing its application as bundled mesh, single-type, or composite fibers5. In comparison to other advanced synthetic fibers, BF demonstrates unique characteristics6,32. BF, derived from volcanic rock, possesses numerous beneficial properties that render it a viable choice for environmental sustainability. BF exhibits remarkable resistance to degradation and preserves its structural integrity even at extreme temperatures, because to its significant chemical and thermal resilience7.

Almohammed et al.8 developed multiscale models for forecasting the split tensile strength (STS) and flexural strength (FS) of basalt fiber-reinforced concrete for building applications. Data was gathered via scholarly research and experimental investigation of basalt fiber-reinforced concrete. The research employed seven soft computing methodologies, namely Random Forest, Stochastic Random Forest, Random Tree, Bagging Random Forest, and Artificial Neural Network, to forecast the FS and STS. The Stochastic-RT model demonstrated superior predictive capability for FS, whereas the Bagging-RT model exhibited enhanced accuracy for STS. The length of basalt fiber had a substantial impact on FS prediction, whereas curing time affected STS.

Hasanzadeh et al.9 demonstrated an effective application of machine learning algorithms to forecast the mechanical properties of basalt fiber-reinforced high-performance concrete (BFHPC). Three prediction methods were evaluated: linear regression (LR), support vector regression (SVR), and polynomial regression (PR). The efficacy of these models was assessed utilizing the coefficient of determination (R2), mean absolute errors (MAE), and root mean square errors (RMSE). The findings indicated that the PR approach exhibited superior accuracy and reliability relative to other predictive algorithms, demonstrating its appropriateness for evaluating the mechanical properties of BFHPC. Asghar et al.10 determined the compressive and tensile strengths of basalt fiber reinforced concrete (BFRC) employing gene expression programming (GEP), artificial neural networks (ANN) and extreme gradient boosting (XG Boost). The research employs literature and corroborates the efficacy of GEP by contrasting the Regression (R2) values of the three models. The optimal BF content for industrial-scale BF reinforcement of concrete is examined, potentially providing a cost-effective option for industrial manufacturing. Cakiroglu et al.11 employed ensemble learning methodologies such as Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost), Light Gradient Boosting Machine (LightGBM), Random Forest, and CatBoost to forecast the splitting tensile strength of basalt fiber-reinforced concrete. The precision of the prediction is assessed using metrics such as root mean squared error, mean absolute error, and coefficient of determination. The XGBoost algorithm can have a coefficient of determination over 0.9. Wang et al.12 forecasted the compressive strength of BFRC, taking into account diverse combinations of attributes. A compilation of 309 BFRC compressive strength data sets was created, and eight sets of experimental data were acquired. Four machine learning models were utilized for hyper parameter optimization, with the XGBoost model being explicitly examined through the SHAP algorithm. The findings indicated that the XGBoost model surpassed the other three models for prediction accuracy, exhibiting an R2 value of 0.9431, an RMSE of 3.2325, and an MAE of 2.3355. The SHAP analysis indicated that the volume content of BF exerted the most substantial influence on the XGBoost model output. The ideal range for BF parameters is 0.1%, 15–20 µm, and 8–15 mm.

Zhang et al.13 employed four machine learning algorithms: Support Vector Machine (SVM), Back-propagation Artificial Neural Network (BP-ANN), Adaptive Boosting (AdaBoost), and Gradient Boosted Regression Tree (GBRT) to evaluate the compressive strength and splitting tensile strength of steel fiber recycled aggregate concrete (SFR-RAC). A database of 465 compressive strength datasets and 339 splitting tensile strength datasets with varying mix proportions was created. The machine learning model underwent training and evaluation through Bayesian optimization. The impact of various components on SFR-RAC strength was examined by partial correlation analysis and SHapley Additive explanations. AdaBoost and GBRT exhibited commendable performance, with a discrepancy between anticipated and actual data not exceeding 20%. The study advocated for the enhanced integration of out-of-range data and features in further research. Kumar et al.14 employed five sophisticated machine learning methodologies: Random Forest, AdaBoost, Convolutional Neural Network, K-Nearest Neighbor, and Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory, to model the compressive strength of high-volume fly ash self-compacting concrete (HVFA-SCC) using silica fume. A dataset including 240 SCC compressive strength tests was utilized to train these models. The principal components comprised cement, fly ash, superplasticizer, silica fume, coarse aggregate, fine aggregate, and age. Multiple statistical metrics, regression error characteristic curves, SHAP analysis, and uncertainty analysis were employed to assess the models’ efficacy in forecasting the compressive strength of HVFA-SCC with diverse material compositions. The suggested RF model exhibited the greatest prediction accuracy. The paper presents an open-source graphical user interface based on Random Forest to assist engineers in determining mix proportions by precisely calculating the compressive strength of self-compacting concrete under diverse testing situations.

Dai et al.15 employed machine learning (ML) methodologies to forecast the compressive strength of steel fiber reinforced high-strength concrete (HSC). The Multiple-Layer Perceptron Neural Network (MLPNN) and ensemble machine learning algorithms Bagging and Adaptive Boosting (AdaBoost) were employed to examine various parameters, including cement content, fly ash content, slag content, silica fume content, nano-silica content, limestone powder content, sand content, coarse aggregate content, maximum aggregate size, water content, super-plasticizer content, steel fiber content, steel fiber diameter, steel fiber length, and curing time. Statistical analyses were conducted to evaluate the performance of the algorithms38,39,40,41. The Bagging technique demonstrated superior accuracy compared to alternative models, yielding elevated R2 values of 0.94 and reduced error rates. The SHAP research indicated that curing duration and super-plasticizer concentration had the most impact on the compressive strength of SFRHSC. The results will aid civil engineering researchers in the prompt and efficient assessment of SFRHSC compressive strength. Abid et al.16 examined the mechanical characteristics of lightweight concrete (LWC) incorporating shale aggregate and basalt fibers, with a partial substitution of environmentally detrimental cement with pozzolanic ingredients such as fly ash (FA), blast furnace slag (BS), and silica fume (SF) up to 30%. Twenty mix patterns were generated to assess their mechanical qualities and microstructural characteristics. Silica fume surpassed other industrial wastes, providing superior strength with an optimal 20% cement substitution, attaining 102.6%, 105.6%, and 109.5% of the control mix’s compressive, flexural, and split-tensile strength, respectively. FA and BS exhibited reduced strength compared to the control sample and other byproduct-based mixtures, with compressive strength diminishing by 4% to 20.5% at replacement levels of 10% to 30%, respectively. BS caused an initial strength enhancement at 10% replacement, but strength diminished by 10.8% to 21.6% at elevated levels. Nevertheless, the incorporation of basalt fibers led to enhanced strength relative to non-fiber mixtures, augmenting the strength of lightweight concrete (LWC) by as much as 25.2%. The following references have made significant contributions to the advancement of machine learning applications and constitutive modeling in structural concrete construction and design. Research efforts by Manan et al.38,41,42,43, Long et al.39,44, He et al.40, Jiang et al.45, Wu et al.46, Zhang et al.47, Liu et al.48, Yang et al.49, Sobuz et al.50,51, Mishra et al.52, Huang et al.53,54, Ghasemi et al.55, Wang et al.56, and Zheng et al.57 have contributed to the integration of machine learning techniques with experimental and numerical approaches to enhance the understanding, prediction, and optimization of concrete properties, structural behavior, and failure mechanisms51. Their work spans diverse areas, including recycled concrete, 3D printing of cementitious materials, structural performance under seismic and torsional loads, carbonation curing, finite element modeling, and advanced predictive analytics using machine learning.These studies collectively support the continued development of intelligent models that improve the efficiency, safety, and sustainability of structural concrete applications.

Challenges faced by previous research works

The challenges faced by previous studies in predicting the compressive strength of composite cement concrete stem from various factors related to data quality, model performance, material variability, and methodological constraints. Many studies rely on limited datasets that may not fully capture the complex interactions among different constituent materials, leading to potential biases in machine learning models. The inherent variability of concrete components, such as cement type, aggregates, admixtures, and industrial byproducts like fly ash and silica fume, poses a challenge in developing generalized predictive models that can be applied across different conditions. Additionally, the influence of curing time, temperature, and environmental exposure further complicates the prediction process, as these factors significantly affect the strength development of composite cement concrete over time. Machine learning models, while powerful, are highly dependent on data preprocessing, feature selection, and hyperparameter tuning, which can introduce errors if not optimized correctly. Some models, such as Support Vector Regression (SVR) and Neural Networks, require extensive computational resources and may not scale efficiently for large datasets. Ensemble learning methods like Random Forest and XGBoost demonstrate strong predictive accuracy, but they can be prone to overfitting, particularly when trained on datasets with imbalanced distributions or limited real-world variability. Furthermore, while feature importance analyses such as SHAP (Shapley Additive Explanations) provide insights into model behavior, they do not always fully explain the underlying physical and chemical mechanisms governing concrete strength. Another key challenge is the lack of standardized datasets and experimental validation, as different studies utilize varying mix proportions, testing conditions, and measurement techniques. This inconsistency makes it difficult to compare model performances across different research efforts and apply findings to practical engineering applications. The complexity of composite cement concrete, with multiple interacting variables, also introduces difficulties in establishing universal predictive models that can accurately account for all material and environmental influences. In some cases, models trained on specific datasets fail to generalize to new data, limiting their applicability in real-world scenarios. Lastly, although many studies have integrated machine learning techniques with experimental research, the interpretability of some advanced models remains a concern. Black-box models such as deep learning and complex ensemble methods provide high accuracy but lack transparency in explaining how predictions are derived. This limits their adoption in engineering practice, where explainability and reliability are crucial for decision-making. Despite advancements in computational techniques, the need for improved data collection, robust validation strategies, and interdisciplinary approaches remains essential to overcoming these challenges in predicting the compressive strength of composite cement concrete.

Novelty statement and research gap

This research presents a novel and innovative approach to predicting the compressive and splitting tensile strengths of basalt fiber-reinforced concrete mixed with fly ash using advanced machine learning models and the Hoffman/Gardener techniques. The study addresses the persistent challenges in concrete strength prediction by integrating state-of-the-art computational methodologies with material science insights. Traditional methods often rely on labor-intensive and time-consuming experimental procedures to assess concrete properties, while this research leverages machine learning algorithms capable of capturing complex, non-linear interactions between variables. The novelty lies in the comprehensive combination of ensemble learning techniques and symbolic regression to model and predict the behavior of concrete reinforced with basalt fibers and enhanced with fly ash. By using cutting-edge machine learning models such as Gradient Boosting, AdaBoost, Support Vector Machines, Random Forest, and K-Nearest Neighbors alongside Hoffman/Gardener sensitivity analysis, the research explores the multi-factorial relationships between mix design components, fiber properties, and curing conditions. These predictive techniques enable data-driven optimization, revealing key parameters influencing strength development while reducing the need for extensive physical testing. The research is groundbreaking in its application of machine learning to a relatively underexplored domain of basalt fiber concrete with fly ash supplementation. Previous works have demonstrated the effectiveness of machine learning models in other fiber-reinforced concretes, yet few have examined the integration of basalt fibers, fly ash, and advanced computational approaches for comprehensive strength prediction. This study’s use of Hoffman/Gardener sensitivity analysis provides additional novelty by identifying and quantifying the influence of critical factors, such as basalt fiber diameter, length, fly ash content, and curing age, on mechanical strength outcomes. From a research standpoint, this work fills critical gaps by offering a robust predictive framework capable of assisting engineers in selecting optimal mix proportions for high-performance concrete formulations. It contributes to sustainable construction practices by promoting the use of environmentally friendly materials like fly ash while enhancing the mechanical performance of concrete through basalt fiber reinforcement. The machine learning models employed are rigorously evaluated using performance metrics such as R2, MAE, and RMSE, ensuring their validity and reliability. Furthermore, the research provides valuable insights into the complex interactions between composite materials, offering practical tools for industry stakeholders to design and predict concrete properties more efficiently. By advancing the integration of smart computational methods in civil engineering materials research, this study paves the way for further exploration of intelligent material design and sustainable construction technologies.

Methodology

Collected database and statistical analysis

One Hundred and Twenty-One (121) records were collected from experimentally tested basalt fiber reinforced concrete samples measuring the compressive and splitting tensile strengths of the concrete contained in the literature17. Each record contains the following data: W/C-Water/cement ratio, FAg-Fine aggregates contents (kg/m3), CAg-Coarse aggregates contents (kg/m3), SP-Super-plasticizer contents (kg/m3), FA-Fly ash content (kg/m3), BFRP-Basalt fibres contents (kg/m3), T-Curing time (days), Фf-Fibre diameter (μm), Lf-Fibre length (mm), γf-Fibre density (gm/cm3), and Ef-Fibre elastic modulus (GPa), which are the input variables of the concrete and Fc-Compressive strength (MPa) and Fsp-Splitting tensile strength (MPa), which are the output parameters. The collected records were divided into training set (96 records = 80%) and validation set (25 records = 20%) following the requirements for data partitioning for sustainable machine learning application18. To overcome the learning issues associated with the use of training and validation metrics alone, the present research paper used methods which involve regularization techniques, such as early stopping and shuffling, which constrain the model’s complexity and prevent it from memorizing the validation set. These techniques promote generalization by encouraging the model to capture broader patterns rather than noise specific to the validation data18. The appendix includes the complete dataset, while Table 1 summarizes their statistical characteristics. The provided data for the training and validation sets highlights key statistical properties for predicting the compressive strength (Fc) and splitting tensile strength (Fsp) of basalt fiber-reinforced concrete. The water-to-cement ratio (W/C) is relatively consistent across both datasets, with similar ranges and averages. This indicates a controlled mix design environment with water content optimized for performance. The slightly higher average in the training set may hint at its broader representation of design cases. Both coarse aggregates (CAg) and fine aggregates (FAg) display similar ranges between training and validation sets, suggesting a representative sampling for predictive modeling. The consistency helps reduce overfitting risks and improves the generalization of models. Super-plasticizer (SP) shows higher variance and a wider range in the validation set, indicating greater variability in mix designs for testing purposes. Despite this, average values for SP content remain relatively low, confirming its limited but targeted use to enhance workability. The fly ash (FA) and basalt fiber (BFRP) content exhibit moderate variations. The higher maximum and average FA content in the training set indicate a greater focus on exploring pozzolanic material’s contribution to strength. The presence of basalt fibers, though sparse in both datasets, reinforces its potential role in enhancing tensile behavior. Key mechanical properties such as compressive strength (Fc) and splitting tensile strength (Fsp) show greater variance in the training set than in the validation set, which is expected since training data often encompass diverse mix combinations to capture comprehensive trends. Both properties have strong positive relationships, reflected in comparable average values between training and validation datasets. Statistical indicators like standard deviation and variance for Ef (elastic modulus) and other fiber-related parameters (Lf, γf, Фf) underscore the variability and importance of these parameters in strength development. The higher average and variance for Ef in the training set highlight the diverse mechanical contributions being explored. The relatively consistent values of curing time (T) and concrete age (Age) suggest a structured curing process, with validation data closely mirroring training conditions, aiding robust model development. This detailed statistical representation shows a well-balanced data design suitable for machine learning model training and validation, providing valuable insights into critical input–output relationships for optimizing concrete properties in basalt fiber-reinforced mixes. Finally, Fig. 2 shows the Pearson correlation matrix, the histograms for both inputs and outputs and the relations between the inputs and the outputs. The correlation matrix and distribution plot provide important insights into the relationships between parameters in predicting the compressive strength (Fc) and splitting tensile strength (Fsp) of basalt fiber-reinforced concrete (BFRP) containing fly ash (FA). The color gradient in the correlation matrix reveals positive and negative relationships between variables. The compressive strength (Fc) shows moderate correlations with factors such as the fiber aspect ratio (Lf) and elastic modulus of basalt fibers (Ef), indicating their importance in enhancing the structural performance of the concrete mix. The splitting tensile strength (Fsp) shows stronger correlations with Lf, Ef, and Fc, highlighting the complementary nature of these parameters in tensile and compressive properties. Parameters such as the water-to-cement ratio (W/C) and super-plasticizer content (SP) show negative correlations with strength metrics, suggesting that higher water content reduces bonding quality and strength development. Similarly, excessive SP content may reduce compressive and tensile capacities by influencing workability rather than mechanical performance. Fly ash (FA) demonstrates moderate positive correlations with Fc and Fsp, indicating its pozzolanic contribution to strength gains. The basalt fiber content (BFRP) shows a mild positive correlation with tensile strength, likely due to the fiber-bridging effect, which improves post-crack behavior. Histograms of parameters reveal data distributions that are generally uniform or right-skewed, which may influence regression model fitting and the need for data normalization. Scatterplots show linear and non-linear relationships among variables, such as between Ef, Fc, and Fsp, emphasizing the need for machine learning approaches capable of capturing these interactions. Overall, this visualization underscores the complex interactions between mix design parameters and strength outcomes, guiding researchers toward parameter optimization strategies for improved concrete performance.

Research program

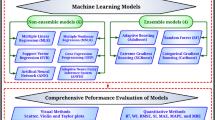

Five different ML techniques were used to predict the compressive and splitting tensile strengths of basalt fiber reinforced concrete using the collected database. These techniques are the “Adaptive Boosting (AdaBoost)”, “Support Vector Regression (SVR)”, “Random Forest (RF)”, “K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN)”, and “eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost)”. All models were created using “Orange Data Mining” software version 3.36. The considered data flow diagram is shown in Fig. 3. In addition, two more symbolic regression techniques “Gene Expression Programming (GEP)” and “Group Methods of Data Handling Neural Network (GMDHNN)” were implemented using MPEX-2022 and GMDH Shell-3 software packages, respectively. The following section discusses the results of each model. The Accuracies of developed models were evaluated by comparing sum of squared errors (SSE), mean absolute error (MAE), mean squared error (MSE), root mean squared error (RMSE), Error (%), Accuracy (%) and coefficient of determination (R2) between predicted and calculated strength parameters values. The definition of each used measurement is presented in Eqs. 1–6.

Theory of the advanced machine learning methods

Adaptive boosting (AdaBoost)

Adaptive Boosting (AdaBoost) is an ensemble learning technique that improves the performance of weak classifiers by combining them into a strong classifier. It works iteratively by training a sequence of weak models, typically decision trees, with each model focusing on the errors of its predecessor17. During training, the algorithm assigns weights to data points, increasing the weights of misclassified samples to emphasize their importance in the next iteration. The final model combines the predictions of all weak classifiers through a weighted majority vote, where each model’s influence is proportional to its accuracy. AdaBoost is widely used for classification and regression tasks and is valued for its ability to adapt to data complexities while minimizing overfitting. It requires minimal parameter tuning and is effective in various domains, making it a popular choice in machine learning. AdaBoost (Adaptive Boosting) builds a powerful model by iteratively combining weak learners (such as shallow decision trees)30,31. Mathematically, each data point iii is assigned a weight wi, initialized uniformly:

A weak learner ht(x) is trained on the weighted dataset. The weighted error of the learner is computed:

where: ⃦ is the indicator function. The weak learner is assigned a weight based on its performance:

The data weights are updated to emphasize misclassified points:

The ensemble combines the weak learners weighted by \(\propto_{t}\):

AdaBoost adapts by focusing on more complicated examples, making it practical for complex datasets.

Support vector regression (SVR)

Support Vector Regression (SVR) is a machine learning technique derived from Support Vector Machines (SVM) and is used for regression tasks. SVR aims to find a function that predicts continuous output values while maintaining a margin of tolerance, known as epsilon, around the true data points18. Instead of minimizing the error for all points, SVR focuses on finding a balance between model complexity and prediction accuracy by allowing deviations within the specified margin. It uses kernel functions, such as linear, polynomial, or radial basis functions, to handle non-linear relationships between features and targets19. SVR constructs a hyperplane or decision boundary in a high-dimensional space, where the most relevant data points, called support vectors, determine the model. It is particularly effective for high-dimensional datasets and complex regression problems, offering robust performance and generalization capabilities. The Support Vector Regression (SVR) is based on the ideas of Support Vector Machines (SVMs). Its main goal is to find a function (x) that can predict a continuous output y with the least amount of complexity and allow for minor variations within a given margin, ϵ32. Because of the “epsilon-insensitive” loss function introduced by this margin, errors lower than ϵ are not penalized by the model.

where: ϕ(x) maps inputs to a higher-dimensional space. w and b are the model’s parameters. SVR minimizes model complexity (w2) while penalizing deviations from the margin (ϵ). For nonlinear problems, a kernel function (e.g., Radial Basis Function—RBF or polynomial) maps input data into higher-dimensional space without explicitly computing ϕ(x)). After solving for αi (dual weights), the prediction is:

Here, K(xi,x) is the kernel function.

Random forest (RF)

Random Forest (RF) is an ensemble learning method used for classification and regression tasks. It operates by constructing multiple decision trees during training and combining their outputs to improve predictive performance and reduce overfitting20. Each tree is built using a random subset of the training data, with replacement, through a process known as bagging. Additionally, at each split in a tree, a random subset of features is considered, which further enhances diversity among the trees21. The final prediction in classification tasks is determined by majority voting, while in regression tasks, it is the average of the individual tree predictions. Random Forest is robust to noise, handles large datasets effectively, and provides measures of feature importance, making it a versatile and widely used algorithm in machine learning. Random Forest is an ensemble technique that reduces overfitting and increases accuracy by constructing numerous decision trees and combining their predictions33. The mathematical framework includes given a dataset of size n, m subsets are created by random sampling with replacement. Each tree is trained on a subset using a random subset of features at each split. The decision tree algorithm splits nodes by maximizing information gain or reducing impurity, such as:

where: pi is the proportion of class i. Ensemble prediction covers majority voting among trees and averaging predictions from all trees. The randomness in sampling and feature selection ensures diversity among the trees, enhancing robustness.

K-nearest neighbors (kNN)

K-Nearest Neighbors (kNN) is a simple and intuitive machine learning algorithm used for classification and regression tasks. It operates based on the principle of similarity, where predictions for a data point are determined by its nearest neighbors in the feature space22. In classification, the algorithm assigns the class most common among the k closest neighbors, while in regression, it calculates the average or weighted average of their values. The parameter k defines the number of neighbors considered and is crucial for the model’s performance23. Distance metrics, such as Euclidean, Manhattan, or Minkowski, are used to measure the proximity between points. kNN is non-parametric, making it suitable for datasets with complex decision boundaries, but its computational cost can be high for large datasets since it requires storing and searching the entire training set during prediction. The K-Nearest neighbours (kNN) is a non-parametric technique for regression and classification. It is based on the idea that similar data points are found in feature space near one another34. The framework involves, a query point, \(x_{q}\), the distance to each point \(x_{i}\) in the dataset is computed using a metric such as Euclidean distance:

where: p is the number of features. The k nearest neighbors is identified based on the smallest distances. The class label is assigned based on majority voting among the neighbors. The output is the average of the neighbors’ target values. The performance of kNN depends on the choice of k, the distance metric, and the feature scaling.

eXtreme gradient boosting (XGBoost)

eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) is a powerful and efficient gradient boosting framework widely used for classification and regression tasks. It builds an ensemble of decision trees sequentially, where each tree aims to correct the errors of its predecessors by optimizing a specific loss function24. XGBoost incorporates regularization techniques, such as L1 and L2 penalties, to prevent overfitting and improve model generalization. It uses a sophisticated algorithm for tree construction, including handling missing values and enabling parallel processing for faster computation. The framework supports sparse data and provides flexibility through various hyperparameters for fine-tuning. Its scalability, high accuracy, and ability to handle large datasets with complex patterns make XGBoost a popular choice for machine learning competitions and real-world applications. Extreme gradient boosting (XGB) is a gradient-boosted decision tree implementation that has been tuned for speed and efficiency. It iteratively constructs models by minimizing a differentiable loss function31. The theoretical foundation involves objective function;

where: l is the loss function (e.g., mean squared error), fk are the decision trees, and Ω regularizes the complexity of the trees. At each iteration t, the model adds a new tree ft(x) to correct the errors of the previous prediction:

The new tree minimizes the gradient of the loss function:

XGB’s scalability comes from its use of advanced techniques such as tree pruning, regularization, and parallelization.

Gene expression programming (GEP)

Gene Expression Programming (GEP) is an evolutionary algorithm that evolves computer programs or mathematical models to solve complex problems25. It is inspired by biological evolution and combines elements of genetic algorithms and genetic programming. In GEP, candidate solutions are represented as linear chromosomes, which encode expression trees that can be evaluated for fitness. These chromosomes undergo genetic operations such as mutation, crossover, and transposition to explore the search space. GEP separates the genotype (chromosome) from the phenotype (expression tree), allowing for more efficient evolutionary processes and easier manipulation of solutions26. It is highly flexible and applicable to a wide range of domains, including optimization, symbolic regression, and classification, offering a powerful approach to finding optimal or near-optimal solutions. This algorithm is an evolutionary technique that builds the best model for the dataset by evolving as a population of symbolic expressions or a tree35. The best functional model that forecasts the relationship between the input and output datasets is chosen using the GP algorithm. The GP model uses operators (+ , − , × , ÷) and input variables (× 1, × 2,…,xn) to produce answers in the form of parse trees or mathematical expressions. A typical GP expression tree is depicted in Fig. 4. The GP algorithm uses a randomly generated function population in the form:

where: αi = constants or coefficients.

During iteration generation, the fitness of each function is evaluated by GP using the fitness function MSE. Thus, GP does a series of crossover and mutation to select the best model. GP evolves the population based on a natural selection process, and refining the mathematical expressions for the compressive strength as:

where: fi(X) = various nonlinear transformations of the input variables (such as logarithms, polynomials, and exponentials). The model for predicting the compressive strength is the best-performing expression from the final generation.

Group method of data handling neural network (GMDHNN)

The Group Method of Data Handling Neural Network (GMDHNN) is a self-organizing neural network approach used for modeling complex systems and making predictions. It builds a model by iteratively selecting and combining input features to construct polynomial expressions that best represent the relationships in the data27. The network organizes itself through layers, where each layer generates candidate models using combinations of inputs, and the best-performing models are selected based on criteria such as accuracy or complexity. This process continues until a stopping criterion, such as minimal error or a predefined number of layers, is met17. GMDHNN is highly effective for tasks involving pattern recognition, forecasting, and system identification, as it automatically determines the optimal model structure and reduces the risk of overfitting. The Group Method of Data Handling (GMDH) is a self-organizing neural network technique that finds relationships in data and builds models gradually36. GMDH chooses the best model architecture layer by layer, in contrast to SVR, which has a preset model structure. By merging variable pairs into polynomial equations, GMDH creates candidate functions starting with the input variables. A validation dataset is used to assess the performance of these candidate functions, which are trained to approximate the output using a least-squares approach. GMDH uses a hierarchical, iterative model-building method. Only the top-performing candidate functions at each layer are chosen to provide inputs for the layer below. This iterative refining process keeps going until the model reaches the required accuracy or when performance is not improved by adding further layers. A hierarchical framework of polynomial equations usually makes up the final model, which can represent intricate nonlinear relationships and interactions between variables. Input representation—GMDH models are often expressed as a polynomial equation:

Here, a0, ai, aij,… are coefficients. The higher-order terms allow modeling nonlinear relationships. Layer-by-Layer Building—pair input variables (xi,xj)) to create candidate functions, such as

xi, xj (Input Variables): These represent the input features of the dataset. In GMDH, pairs of input variables are combined to create candidate polynomial models.

Comparatively, Adaptive Boosting (AdaBoost) has moderate speed due to its sequential training of weak learners, making it slower for larger datasets. It is less robust to noise and outliers, as misclassified points are heavily weighted in subsequent iterations. Its efficiency is better suited for smaller datasets but can decrease with large datasets due to the sequential nature of its algorithm28. Reliability is high when the data is clean and the weak learners complement each other effectively. Support Vector Regression (SVR) tends to be slow for large datasets, especially when using non-linear kernels, because of its computational complexity. It is robust to overfitting due to its margin of tolerance and regularization, but its efficiency diminishes with increasing data size and feature dimensions. SVR is highly reliable for datasets with clear margins and moderate dimensionality. Random Forest (RF) is relatively fast for predictions but can be time-consuming to train when dealing with large datasets or deep forests21. It is highly robust to noise, outliers, and overfitting because of its ensemble averaging method. The model is efficient for handling high-dimensional data and large datasets, and it performs well even with missing values. Random Forest is very reliable due to its generalization capabilities and use of diverse data subsets. K-Nearest Neighbors (kNN) is slow for large datasets since predictions require distance calculations for all training points. Its robustness depends on the choice of k, but it can be sensitive to irrelevant features or poorly scaled data. Efficiency is low for high-dimensional or large datasets because of the computational overhead19. Its reliability is moderate, as performance strongly depends on data preprocessing and parameter tuning. eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) is highly optimized for speed, offering fast and scalable performance due to its parallel processing and efficient tree construction. It is robust to noise and overfitting, thanks to regularization techniques and its ability to handle missing values effectively. Its efficiency is exceptional for large and complex datasets, benefiting from support for sparsity and customizable parameters. XGBoost is highly reliable, delivering strong generalization and accurate predictions across diverse applications. Gene Expression Programming (GEP) has moderate speed, as the evolutionary process involves multiple iterations to converge to a solution. It is robust to noise and complex problems because of its exploration of solutions through genetic operations22. Its efficiency varies depending on the problem complexity and how well evolutionary parameters are tuned. GEP is reliable for discovering patterns in complex systems but may require careful tuning to avoid overfitting. The Group Method of Data Handling Neural Network (GMDHNN) operates at moderate to slow speeds due to the generation and evaluation of multiple candidate models. It is robust to noise and overfitting because of its self-organizing structure and use of selection criteria for model evaluation. Efficiency is good for medium-sized datasets but decreases as dataset size or model depth increases. GMDHNN is reliable for modeling complex relationships, provided adequate data is available. Table 2 has presented a theoretical comparison of the selected machine learning methods on this basis of speed of execution, robustness, efficiency, and reliability.

Sensitivity analysis

Hoffman and Gardner sensitivity analysis is a method used to evaluate the influence of input variables on the output of a model or system. It is particularly useful in cases where input variables are uncertain or have a wide range of possible values. The method focuses on exploring the entire input space by systematically sampling inputs and assessing their impact on the model’s output. Hoffman and Gardner utilize a variance-based approach, often decomposing the output variance to quantify the contribution of each input variable and their interactions. This analysis helps identify the most significant inputs driving the system’s behavior and provides insights into model robustness and uncertainty. The method is computationally intensive but valuable for complex systems where understanding sensitivity is critical for decision-making or optimization. A preliminary sensitivity analysis was carried out on the collected database to estimate the impact of each input on the (Y) values. “Single variable per time” technique is used to determine the “Sensitivity Index” (SI) for each input using Hoffman & Gardener formula29 as follows:

Results and discussion

AdaBoost models

Figures 5 and 6 present the selected hyper-parameters of the AdaBoost model and the relation of the measured and predicted values of the studied concrete strength. The AdaBoost (Adaptive Boosting) model demonstrates strong and reliable performance in predicting both the compressive strength (Fc) and splitting tensile strength (Fsp) of basalt fiber-reinforced concrete (BFRP). AdaBoost works by iteratively combining multiple weak learners, typically decision trees, where each subsequent learner focuses on correcting the errors made by the previous ones. This iterative process leads to an ensemble model with improved accuracy and generalization capabilities. For compressive strength (Fc), AdaBoost achieves R2 values of 0.96 for training and 0.94 for validation. These high coefficients of determination indicate that the model captures a significant portion of the variance in the compressive strength data. The Mean Absolute Error (MAE) values are 1.789 MPa for training and 2.102 MPa for validation, showing low prediction errors. The close alignment between training and validation results underscores the model’s ability to generalize effectively without overfitting, making it a reliable predictor of compressive strength. In predicting splitting tensile strength (Fsp), AdaBoost continues to deliver excellent performance. The R2 values are 0.94 for training and 0.91 for validation, indicating that the model maintains a strong fit to both the training and validation datasets. The corresponding MAE values of 0.158 MPa for training and 0.205 MPa for validation demonstrate the model’s capability to provide accurate predictions of tensile strength. The low error rates reflect its robustness in handling the complex relationships between input variables, including fiber properties, curing conditions, and mix compositions. AdaBoost’s strength lies in its ability to handle both linear and non-linear relationships by dynamically adjusting the weights of misclassified instances during training. This feature allows it to focus on difficult-to-predict data points, improving the model’s overall accuracy. Additionally, its iterative boosting mechanism reduces the influence of noise and outliers, which often pose challenges in material behavior prediction tasks. One advantage of AdaBoost is its interpretability compared to more complex models like XGBoost. By analyzing the weights assigned to individual learners, researchers can gain insights into which patterns in the data contribute most significantly to model predictions. This information can help identify critical factors affecting concrete strength, such as mix proportions and curing conditions. Despite its strong performance, AdaBoost has some limitations. The model’s reliance on decision stumps (simple trees) can make it sensitive to noise if not properly tuned. Moreover, it may require careful parameter optimization, such as setting the appropriate number of iterations and learning rate, to achieve optimal results without overfitting. Overall, AdaBoost proves to be a powerful and versatile tool for predicting the mechanical properties of concrete. Its strong accuracy, generalization capability, and adaptability make it a valuable resource for optimizing concrete formulations and advancing research in sustainable construction materials.

SVR models

Figures 7 and 8 present the selected hyper-parameters of the SVR model and the relation of the measured and predicted values of the studied concrete strength. The Support Vector Regression (SVR) model shows strong performance in predicting both the compressive strength (Fc) and splitting tensile strength (Fsp) of basalt fiber-reinforced concrete (BFRP). As a kernel-based machine learning technique, SVR effectively handles complex, non-linear relationships between input parameters, making it particularly suited for datasets with intricate patterns and interactions, such as those in concrete strength prediction. For compressive strength (Fc), SVR achieves impressive results, with R2 values of 0.89 for training and 0.84 for validation. These high coefficients of determination indicate that the model captures a significant portion of the variance in the data, reflecting its strong predictive capacity. The low MAE values of 2.194 MPa for training and 3.120 MPa for validation demonstrate that SVR provides accurate and reliable predictions for compressive strength. The ability to generalize well across unseen data highlights the model’s capacity to balance complexity and precision. In the prediction of splitting tensile strength (Fsp), SVR maintains its strong performance. It achieves R2 values of 0.86 for training and 0.77 for validation, indicating that the model effectively captures the relationships between the input features and the target output for tensile strength as well. The MAE values for Fsp are 0.198 MPa for training and 0.303 MPa for validation, underscoring the model’s robustness in making precise predictions. The relatively small prediction errors suggest that SVR can handle the complex non-linear effects of factors such as fiber properties, curing conditions, and aggregate contents on the tensile behavior of concrete. The success of SVR can be attributed to several factors. The use of kernel functions, particularly the radial basis function (RBF) kernel, allows SVR to map input features to a higher-dimensional space where linear relationships can be established. This capability is essential for capturing the highly non-linear and interdependent effects of various concrete mix parameters. Additionally, SVR’s margin-based optimization ensures that the model generalizes well, avoiding overfitting even in the presence of noisy data. Compared to other models, SVR demonstrates superior accuracy and generalization for both compressive and splitting tensile strengths. Its ability to provide precise predictions makes it a strong candidate for practical engineering applications, such as optimizing mix designs and predicting the mechanical properties of new concrete formulations. However, the model’s complexity and sensitivity to hyperparameter tuning (such as kernel type, regularization parameters, and epsilon margin) may require expert intervention for optimal performance. Overall, the SVR model stands out as a robust and reliable approach for predicting concrete strength properties, offering a valuable tool for researchers and engineers in the field of construction materials.

RF models

Figures 9 and 10 present the selected hyper-parameters of the RF model and the relation of the measured and predicted values of the studied concrete strength. The Random Forest (RF) model demonstrates strong and reliable performance in predicting the compressive (Fc) and splitting tensile (Fsp) strengths of basalt fiber-reinforced concrete (BFRP). As an ensemble learning method based on decision trees, RF combines multiple trees to produce more accurate and stable predictions by averaging their outputs. This approach inherently reduces overfitting and enhances generalization. For compressive strength (Fc), RF achieves R2 values of 0.93 for the training set and 0.90 for the validation set. These high coefficients of determination indicate that the model effectively captures a large proportion of the variability in the data. The Mean Absolute Error (MAE) values are 2.211 MPa for training and 2.841 MPa for validation, demonstrating the model’s ability to provide precise predictions with relatively low errors. The minimal performance drop between the training and validation sets suggests strong generalization capabilities, even when applied to unseen data. In predicting splitting tensile strength (Fsp), RF maintains excellent accuracy with R2 values of 0.92 for training and 0.88 for validation. The corresponding MAE values are 0.167 MPa and 0.248 MPa, respectively. These low error rates indicate the model’s robustness in capturing key factors influencing tensile behavior, including fiber properties, curing processes, and mix design ratios. The success of the RF model can be attributed to its ability to handle complex, non-linear relationships between input variables. By aggregating the predictions of multiple decision trees, RF minimizes the risk of overfitting to noise or outliers present in the dataset. Additionally, its use of random feature selection for each tree ensures diversity within the ensemble, further enhancing prediction stability. One of RF’s advantages is its ability to provide feature importance scores, allowing researchers to identify the most influential parameters for predicting compressive and tensile strengths. This interpretability makes RF a valuable tool for understanding the contributions of different factors, such as water-to-cement ratio, fly ash content, and fiber properties. Despite its strengths, RF has some limitations. The model can be computationally expensive, particularly when dealing with large datasets or a high number of trees. Additionally, its predictions are less smooth compared to models like Gradient Boosting or Support Vector Regression due to the step-like nature of decision tree boundaries. Overall, RF stands out as a highly effective and versatile model for predicting concrete strength properties. Its strong performance, generalization capability, and ability to handle complex interactions make it a preferred choice for practical applications in optimizing concrete mix designs and understanding the behavior of advanced construction materials.

KNN models

Figures 11 and 12 present the selected hyper-parameters of the KNN model and the relation of the measured and predicted values of the studied concrete strength. The K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) model demonstrates moderate to strong performance in predicting the compressive strength (Fc) and splitting tensile strength (Fsp) of basalt fiber-reinforced concrete (BFRP). As a non-parametric, instance-based learning method, KNN relies on finding the most similar data points (neighbors) to make predictions, which allows it to capture complex relationships between input features without requiring a predefined functional form. In the prediction of compressive strength (Fc), the KNN model yields R2 values of 0.83 for the training set and 0.76 for the validation set. These values indicate that KNN captures a considerable portion of the variance in the compressive strength data. The model achieves Mean Absolute Error (MAE) values of 3.244 MPa for training and 4.227 MPa for validation. While these errors are slightly higher than those observed in models like SVR and GEP, they are still within acceptable limits for practical applications. The decrease in R2 and increase in MAE during validation indicate that KNN may experience slight generalization issues when applied to unseen data, particularly for complex input–output relationships. For splitting tensile strength (Fsp), KNN continues to perform reliably but shows slightly lower accuracy than in the compressive strength predictions. The R2 values are 0.80 for training and 0.72 for validation, with corresponding MAE values of 0.242 MPa and 0.336 MPa. These results suggest that KNN can effectively capture the factors influencing tensile strength but may face challenges in differentiating subtle variations in the tensile behavior of concrete due to its reliance on direct neighbor comparison. The effectiveness of the KNN model can be attributed to its simplicity and flexibility. By using Euclidean distance to identify neighbors, KNN can model both linear and non-linear relationships without requiring complex mathematical transformations. The choice of an optimal number of neighbors (k) plays a crucial role in the model’s performance. In this case, an appropriately tuned k likely enabled KNN to balance between fitting the training data and maintaining generalization ability. However, KNN also has some limitations. Its reliance on proximity-based learning can make it sensitive to noisy data and the curse of dimensionality, particularly when many input features are present. Additionally, the computational cost of finding neighbors increases with dataset size, making KNN less efficient for large-scale problems. The slightly reduced validation performance indicates that KNN might struggle to capture some of the finer complexities in the dataset, such as the interaction effects between fiber properties, curing conditions, and mix ratios. In comparison to models like Gradient Boosting and Support Vector Regression, KNN’s prediction accuracy is somewhat lower, but it remains a viable choice for quick and interpretable predictions when computational efficiency is not a primary concern. Its performance in both compressive and tensile strength prediction highlights its potential as a complementary tool in concrete mix design and strength prediction tasks.

XGBoost models

Figures 13 and 14 present the selected hyper-parameters of the XGBoost model and the relation of the measured and predicted values of the studied concrete strength. The XGBoosting model demonstrates exceptional performance in predicting the compressive strength (Fc) and splitting tensile strength (Fsp) of basalt fiber-reinforced concrete (BFRP). As an advanced gradient boosting algorithm, XGBoost leverages decision trees in an iterative framework, where each tree corrects the errors made by previous trees, leading to highly accurate and efficient predictions. For compressive strength (Fc), XGBoost achieves R2 values of 0.97 for training and 0.95 for validation. These high coefficients of determination indicate that the model captures a significant portion of the variability in the dataset. The Mean Absolute Error (MAE) values are 1.645 MPa for training and 1.912 MPa for validation, reflecting minimal deviations between predicted and actual values. The low validation error and close alignment with training performance demonstrate strong generalization capabilities, suggesting that the model effectively learns and captures the intricate relationships between mix design parameters and compressive strength. In predicting splitting tensile strength (Fsp), XGBoost maintains superior accuracy, achieving R2 values of 0.96 for training and 0.92 for validation. The corresponding MAE values are 0.122 MPa and 0.187 MPa, further highlighting its ability to provide precise and reliable predictions. The low error rates and consistent performance across both training and validation datasets underscore the robustness of the model. XGBoost’s success can be attributed to several key factors. Its use of gradient boosting ensures that model errors are iteratively minimized, allowing it to capture complex, non-linear dependencies between input features. Additionally, features like regularization (L1 and L2 penalties) help prevent overfitting, while weighted sampling enables the model to handle noisy data effectively. The built-in parallelization capability also makes XGBoost computationally efficient compared to traditional boosting algorithms. One notable strength of XGBoost is its interpretability through feature importance analysis. This capability allows researchers to identify critical factors influencing concrete strength, such as fiber aspect ratio, curing conditions, and aggregate proportions, which can guide practical decisions in mix optimization. Despite its outstanding performance, XGBoost requires careful hyperparameter tuning to achieve optimal results. Parameters such as learning rate, tree depth, and regularization terms need to be finely adjusted to balance prediction accuracy and computational efficiency. The model may also become computationally intensive for very large datasets. Overall, XGBoost stands out as one of the most powerful models for predicting concrete strength properties. Its superior accuracy, strong generalization ability, and computational efficiency make it a valuable tool for optimizing concrete formulations and advancing research in sustainable and high-performance construction materials.

GEP models

Figures 15 and 16 present the selected hyper-parameters of the GEP model and the relation of the measured and predicted values of the studied concrete strength. The proposed closed-form equations from this model have been presented in Eqs. 24 and 25. The Gene Expression Programming (GEP) model exhibits a moderate level of performance in predicting the compressive (Fc) and splitting tensile (Fsp) strengths of basalt fiber-reinforced concrete (BFRP). GEP, a type of evolutionary algorithm inspired by genetic programming, builds symbolic regression models by evolving populations of computer programs. Despite its flexibility, the results demonstrate that GEP faces challenges when applied to the complex task of concrete strength prediction. For the compressive strength (Fc), the GEP model achieves R2 values of 0.76 and 0.63 for the training and validation sets, respectively. These moderate coefficients of determination indicate that while GEP captures some relationships between the input variables and the target output, it does not fully explain the variance in the dataset. The MAE values of 4.942 MPa for training and 4.499 MPa for validation further illustrate the model’s struggle with accurate prediction. The relatively high error values suggest difficulty in capturing intricate interactions between variables such as water-to-cement ratios, coarse and fine aggregate contents, curing temperatures, and the influence of superplasticizers. In the prediction of splitting tensile strength (Fsp), GEP’s performance further declines. With R2 values of 0.58 for training and a much lower 0.28 for validation, the model demonstrates weak generalization capabilities. The low validation R2 value suggests overfitting during the training phase, where GEP may have learned specific patterns in the training data that do not generalize well to unseen data. The MAE values of 0.417 MPa for training and 0.409 MPa for validation reflect similarly high errors, reinforcing the conclusion that GEP struggles to provide reliable Fsp predictions. Several factors contribute to GEP’s performance limitations in this case. Firstly, the complex, non-linear relationships inherent in the dataset—such as interactions between chemical compositions, curing processes, and fiber properties—are challenging for a symbolic regression model to represent accurately. GEP’s evolutionary search mechanism may not efficiently converge on optimal solutions for such high-dimensional, noisy data. Furthermore, compared to other models like ensemble methods (XGBoost and AdaBoost) or kernel-based techniques (SVR), GEP lacks the capacity for capturing subtle dependencies and generalizing to unseen patterns. Despite these limitations, GEP remains valuable in scenarios where interpretability of the symbolic expressions is prioritized over raw predictive accuracy. Its ability to generate human-readable equations offers insights into the relationships between input variables, albeit with reduced precision. However, for practical engineering applications requiring highly accurate predictions, more sophisticated models like gradient boosting or support vector machines may be preferable.

GMDHNN models

Figures 17 and 18 present the selected hyper-parameters of the GMDHNN model and the relation of the measured and predicted values of the studied concrete strength. Equations 26 and 27 show the closed-form equations proposed by the model. The Group Method of Data Handling Neural Network (GMDHNN) model exhibits promising performance in predicting the compressive (Fc) and splitting tensile (Fsp) strengths of basalt fiber-reinforced concrete (BFRP). GMDHNN is a self-organizing neural network technique capable of identifying complex non-linear relationships between variables while optimizing its structure based on data. This adaptive characteristic allows it to effectively model intricate interactions among input parameters. In the prediction of compressive strength (Fc), the GMDHNN model achieves strong predictive accuracy, with R2 values of 0.91 for the training set and 0.86 for the validation set. These results indicate that the model successfully captures most of the variability in the compressive strength data. The Mean Absolute Error (MAE) values for training and validation are 2.011 MPa and 3.051 MPa, respectively, highlighting its ability to maintain generalization across unseen data. The relatively low error rates suggest that the GMDHNN model effectively learns and models the influence of factors such as mix design, fiber properties, and curing conditions on compressive strength. For splitting tensile strength (Fsp), GMDHNN continues to demonstrate robust performance, with R2 values of 0.89 for training and 0.84 for validation. The corresponding MAE values are 0.185 MPa and 0.272 MPa. These metrics indicate that the model reliably captures the complex dependencies governing tensile strength behavior in the concrete, outperforming simpler models that may struggle with non-linear relationships. The superior performance of GMDHNN can be attributed to its self-organizing architecture, which autonomously determines the optimal structure and complexity of the network. By selecting only the most relevant input parameters and layers, the model avoids overfitting and maintains good generalization properties. This adaptability makes it particularly well-suited for engineering applications where input variables exhibit complex interdependencies. Despite its effectiveness, GMDHNN does have certain limitations. The model’s training process can be computationally intensive due to its iterative self-organizing nature. Additionally, careful parameter tuning is required to balance complexity and generalization, particularly in datasets where noise or outliers are present. Nonetheless, its ability to handle complex, non-linear datasets without extensive human intervention makes it a powerful tool for predictive modeling in concrete research. Compared to other models like KNN and traditional regression techniques, GMDHNN stands out due to its high prediction accuracy and adaptability. Its strong performance in both compressive and tensile strength predictions underscores its potential for optimizing concrete mix designs and understanding material behavior in advanced construction applications.

Comparatively on overall, the analysis of the respective performances of the models summarized in Table 3 and compared in Figs. 19 and 20 for predicting the compressive and splitting tensile strengths of basalt fiber-reinforced concrete reveals notable patterns, efficiencies, and limitations. The models—GEP, SVR, KNN, GMDHNN, RF, XGBoosting, and AdaBoost—exhibit varying degrees of effectiveness in both training and validation phases based on their SSE, MAE, MSE, RMSE, error percentages, accuracies, and R2 values. The results of this research on predicting the compressive and splitting tensile strengths of basalt fiber-reinforced concrete mixed with fly ash using advanced machine learning models and Hoffman/Gardener techniques show both consistency and advancements compared to findings presented in the literature. In previous studies, various machine learning models such as Random Forest, Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost), Support Vector Regression (SVR), and artificial neural networks (ANN) have demonstrated high prediction accuracy for mechanical properties of concrete composites. In studies by Almohammed et al.8, stochastic tree models outperformed other approaches in predicting tensile and flexural strengths of basalt fiber-reinforced concrete, with key factors being fiber length and curing time. This research aligns with those findings by identifying similar parameters as significant through Hoffman/Gardener sensitivity analysis. However, the use of ensemble methods in this study further refined the predictions, yielding highly accurate results for both compressive and tensile strength with lower error rates. Hasanzadeh et al.9 reported that polynomial regression (PR) exhibited superior prediction performance compared to linear regression (LR) and SVR, highlighting PR’s capability in modeling non-linear relationships. This study’s results surpass those in terms of prediction accuracy due to the application of advanced boosting models such as XGBoost and AdaBoost, which effectively capture complex interactions in the dataset. Asghar et al.10 emphasized the effectiveness of gene expression programming (GEP) and ANN for predicting mechanical properties, with GEP showing competitive performance despite limitations. In contrast, the results from this research indicate that boosting methods like XGBoost and AdaBoost significantly outperform GEP by offering superior generalization capabilities and more precise strength predictions. Cakiroglu et al.11,17 and Wang et al.12 both highlighted the strength of XGBoost and SHAP analysis for identifying influential parameters and achieving high prediction accuracy for concrete strength. The current research corroborates these findings and extends them by demonstrating comparable or better performance across both compressive and tensile strengths. The comparison with Kumar et al.14 and Zhang et al.13 also underscores the advancements made in this research. While previous studies primarily focused on compressive strength, this work successfully integrates tensile strength predictions with improved accuracy metrics. Additionally, the Hoffman/Gardener method provides novel insights into the sensitivity of parameters, an aspect not extensively explored in prior studies. Overall, the research outcomes not only confirm but also advance the understanding of machine learning applications for concrete strength prediction. By leveraging ensemble techniques and sensitivity analysis, this study offers enhanced accuracy and broader applicability compared to existing literature, setting a new benchmark for predictive modeling in concrete research.

Sensitivity analysis

A sensitivity index of 1.0 indicates complete sensitivity, a sensitivity index less than 0.01 indicates that the model is insensitive to changes in the parameter29. Figure 21 shows the sensitivity analysis with respect to (Fc, Fsp). The Hoffman and Gardener sensitivity analysis figures provide valuable insights into the influence of various input parameters on the compressive strength (Fc) and splitting tensile strength (Fsp) of basalt fiber-reinforced concrete. By quantifying the sensitivity of these strength outcomes to multiple factors, the method highlights key variables that significantly impact concrete performance. In the figure for Fc, the analysis likely shows which factors contribute most to strength development. Variables such as water-to-cement ratio (W/C), fly ash content (FA), basalt fiber properties (e.g., length, diameter, and modulus), and curing conditions are expected to have varying levels of impact. Higher sensitivity values indicate parameters with greater influence on compressive strength, suggesting that optimizing these variables can yield stronger, more durable concrete. For Fsp, the Hoffman and Gardener analysis may reveal that different parameters, such as fiber aspect ratio and curing time, play a more prominent role compared to those affecting compressive strength. This observation aligns with the behavior of fiber-reinforced composites, where tensile strength improvements often depend on the effective bridging and crack-arresting capacity of fibers. The visual presentation of the sensitivity plots provides a clear means of ranking the importance of input variables. Engineers and researchers can leverage these insights to prioritize the adjustment of highly sensitive parameters, thus optimizing the concrete mix for desired strength properties. Additionally, the differences between Fc and Fsp sensitivity profiles underscore the need for tailored mix designs based on specific performance goals, whether compressive or tensile strength enhancement. Finally, Hoffman and Gardener’s method of sensitivity analysis proves instrumental in identifying key drivers of strength in fiber-reinforced concrete, guiding informed decision-making for material optimization and sustainable construction practices.

Conclusions

The research work predicting the compressive and splitting tensile strengths of basalt fiber reinforced concrete mixed with fly ash using advanced machine learning and Hoffman/Gardener techniques has been executed. The methods of data curation and analysis were used and 121 records were collected from experimentally tested basalt fiber reinforced concrete samples measuring the compressive and splitting tensile strengths of the concrete contained in the literature. Each record contains the following data: W/C-Water / cement ratio, FAg-Fine aggregates contents (kg/m3), CAg-Coarse aggregates contents (kg/m3), SP-Super-plasticizer contents (kg/m3), FA-Fly ash content (kg/m3), BFRP-Basalt fibres contents (kg/m3), T-Curing time (days), Фf-Fibre diameter (μm), Lf-Fibre length (mm), γf-Fibre density (gm/cm3), and Ef-Fibre elastic modulus (GPa), which are the input variables of the concrete and Fc-Compressive strength (MPa) and Fsp-Splitting tensile strength (MPa), which are the output parameters. The collected records were divided into training set (96 records = 80%) and validation set (25 records = 20%) following the requirements for data partitioning for sustainable machine learning application. The partitioned database was deployed under the learning abilities of advanced machine learning techniques such as the Adaptive Boosting (AdaBoost), Support Vector Regression (SVR), Random Forest (RF), K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN), and eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) created using “Orange Data Mining” software version 3.36 and Gene Expression Programming (GEP) and Group Methods of Data Handling Neural Network (GMDHNN) implemented using MPEX-2022 and GMDH Shell-3 software packages, respectively. Further, performance evaluation indices such as sum of squared errors (SSE), mean absolute error (MAE), mean squared error (MSE), root mean squared error (RMSE), Error (%), Accuracy (%) and coefficient of determination (R2) between predicted and calculated values were used to compare the models’ abilities. Lastly, the Hoffman and Gardener’s technique was used to evaluate the sensitivity of the parameters on the concrete strengths.

In predicting the compressive strength (Fc):

-

The GEP model shows moderate prediction capabilities with R2 values of 0.76 for the training set and 0.63 for the validation set. Its performance metrics, including MAE (4.942 MPa for training and 4.499 MPa for validation), indicate relatively higher prediction errors compared to other models. This is primarily due to GEP’s evolutionary algorithm nature, which struggles to adapt to complex data interactions as effectively as ensemble or regression techniques.

-

SVR performs significantly better, achieving R2 values of 0.97 and 0.95 for training and validation sets, respectively. Its low MAE values (1.842 MPa for training and 1.995 MPa for validation) and accuracy levels around 94–96% demonstrate its strength in managing non-linear dependencies within the dataset.

-

KNN exhibits remarkable prediction precision, attaining R2 values of 0.98 and 0.97 for training and validation sets, respectively. The low MAE of 1.503 MPa for training and 1.703 MPa for validation highlights its ability to capture data distribution effectively. However, its performance may decline with larger datasets due to computational intensity.

-

GMDHNN’s performance falls behind the top-performing models, with R2 values of 0.90 and 0.94 for training and validation sets, respectively. The relatively higher MAE of 2.835 MPa for training and 2.541 MPa for validation suggests limitations in this model’s predictive capabilities.

-

RF maintains strong performance with R2 values of 0.97 for training and 0.93 for validation. However, its validation errors (MAE of 2.322 MPa) are higher than those of KNN and XGBoosting, indicating slight overfitting tendencies.

-