Abstract

With the intensification of agricultural production, the significance of soil biological health and microbial network structure has grown increasingly critical. Replacing chemical fertilizers with organic ones has garnered widespread attention as an effective strategy for enhancing soil quality. This study explored the mechanisms of how partial substitution of chemical fertilizers with organic ones affects the microbial community structure in soybean rhizosphere soil of Albic soil. Potting trials and high-throughput sequencing analysis revealed that, compared with conventional fertilization, the soil ACE and Chao1 diversity indices in the treatment with 75% organic fertilizer substitution significantly increased by 19.49% and 21.02%, respectively. The soil pH, organic matter, total phosphorus (TP), effective phosphorus (AP), and hydrolyzed nitrogen (HN) levels exhibited a marked increase of 4.33%, 18.67%, 20.90%, 23.35%, and 32.97% with high levels of organic fertiliser replacement, as compared to NPK. Meanwhile, the dominant phyla of Proteobacteria and Basidiomycota significantly increased by 36.11% and 286.79%, respectively. LEfSe analysis revealed that the fungal community was more sensitive to the fertilizer application strategy than the bacterial communities. Furthermore, redundancy analysis (RDA) demonstrated that soil pH and organic matter were primary environmental factors influencing microbial community structure. The co-occurrence network analysis showed that the partial utilization of organic fertilizers could strengthen the interrelationships among species, leading to a more complex and dense bacterial network. The findings can offer a significant scientific foundation for refining the fertilization strategies for Albic soil and facilitating the shift from conventional to sustainable agricultural practices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the growing disparity between rapid global population growth and food demand, it is paramount to improve the soil health of low-yielding farmland, stabilize food productivity, and establish a sustainable agricultural technology framework1. Albic soil, as a widespread low-productivity barrier-prone soil distributs in 32 countries all over the world. China has approximately 5.272 million∙hm2 of albic soil, whicn is primarily concentrated in Heilongjiang Province2. Albic soil is an obstacle soil and unproductive with a dense physical structure The predominantly intensive mono-fertilization practices in Heilongjiang Province have exacerbated the “plate-thin-hard” phenomenon of Albic soil3. Therefore, it is necessary to develop fertilization measures to achieve sustainable use of Albic soil cropland in northeastern China4.

The application of organic fertilizers is widely acknowledged as an effective measure to improve soil quality and crop yield. Nonetheless, the nutrients slowly released from organic fertilizers alone cannot meet the demand for crop growth5. The partial replacement of chemical fertilizers with organic fertilizers was practised to increase crop yield, improve soil fertility, and protect soil ecosystems6,7. Partially replacing chemical fertilizers by livestock manure, straw, biochar, and the other organic fertilizers can significantly increase the crop yield, such as corn, wheat, soybean ans son on8,9,10,11. It enhances soil carbon sequestration capacity, stimulates the activity of enzymes critical to nutrient cycling, and reduces carbon and nitrogen loss12. The content of phosphorus, potassium, available phosphorus, quick-acting potassium and other nutrients in soil can be improved because of the application of orgainic fertilizer. It can also stimulate the activitives of enzymes critical to nutrient cycling, including soil urease, invertase, and alkaline phosphatase. As a result, it also leads to a more fertile and balanced soil ecosystem13. Furthermore, partial replacement of chemical fertilizers by organic fertilizers can introduce beneficial microbial populations into the soil, leading to improvement of microbial diversity, enhancement of microbial richness, and promotion the propagation of beneficial microorganisms. The beneficial microorganisms play a pivotal role in nutrient cycling and soil health. And nitrogen-fixing bacteria, phosphorus-solubilizing bacteria, and fiber-decomposing bacteria are regarded as beneficial microorganisms. It has also been demonstrated that the stability of the soil microbial network is strengthened through long-term application of organic fertilizers in conjunction with inorganic fertilizers, with pH and soil organic matter as dominant factors, thereby improving the function of the soil ecosystem14.

As the core of the soil microcosm, the rhizosphere soil is an important site for plants to obtain nutrients and water, as well as a key area for organic matter mineralization and nutrient conversion. Rhizosphere soil microorganisms serve as critical indicators of nutrient interactions between crop roots and soil15.As an important component of the soil ecosystem, the rhizosphere soil microbial community plays crucial roles in key ecological processes such as soil nutrient cycling and conversion, organic matter mineralization, and plant nutrient uptake, which are also influenced by substances secreted by the plant root system16. Research indicates that manipulating rhizosphere soil processes is an effective strategy to improve nutrient utilization and crop productivity17. The partial replacement of chemical fertilizers with organic alternatives represents a beneficial intervention in the rhizosphere soil microbial system18, thereby achieving a more balanced and sustained nutrient supply and stimulating the biological activity of the soil itself, thereby establishing a healthier and more stable inter-root environment, a critical approach to restoring and enhancing the function of the rhizosphere soil19,20.

At present, numerous scholars have studied the effects of organic fertilizers on soil nutrients and microbial community structure under red soil21, saline-alkaline soil22, and other soil types. The close relationship between rhizosphere soil properties and soil microorganisms in their ecosystems have been demonstrated23. However, it is still unclear about the precise mechanisms of the effects of organic fertilizer kinds and substitution dosage on the rhizosphere soil nutrients and community structure, particularly in the specific case of the low-yield-barrier Albic soil type. This study aims to explore how partially replacing chemical fertilizers with organic fertilizers affects nutrient and microbial community structures in Albic soil rhizosphere, and to reveal their interrelationships via potting trials combined with high-throughput sequencing technology. Results or findings can aid in comprehending the potential of partial replacement of chemical fertilizers by organic fertilizers in soil fertility restoration and sustainable agricultural development, offer a scientific foundation for optimizing fertilizer application strategies to enhance soil fertility and crop yields. Furthermore, they can also hold significant theoretical and practical value for advancing agro-ecological transitions and environmental conservation.

Materials and methods

Experimental materials

The test soil was representative of the typical Ablic soil type, derived from the original soil of the 852 farm in Heilongjiang Province. The following nutrient profiles were observed: organic matter 24.03 g/kg, total phosphorus 0.50 g/kg, total nitrogen 1.20 g/kg, total potassium 13.2 g/kg, available phosphorus 7.70 mg/kg, available potassium 103.00 mg/kg, alkaline dissolved nitrogen 186.67 mg/kg, and pH 5.75. The organic fertilizer for testing was naturally composted cow dung.The nutrients of the organic fertilizer were as follows: organic matter 327.00 g/kg total nitrogen 1.38 g/kg, total phosphorus 4.85 g/kg, total potassium 24.2 g/kg, and pH 7.02. The soybean variety planted was Hei Nong 531 with 85% germination and 13.5% moisture content, provided by Soybean Research, Heilongjiang Academy of Agricultural Sciences.

Experimental design

This study was conducted in pots at the potting field of Heilongjiang Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Harbin City, Heilongjiang Province, China (45°41′9.81″N, 126°37′20.07″E). The used pot was 27 cm in diameter and 30 cm in height. All trials were based on the principle of equal nitrogen, with three replications for each treatment.Six fertilization trials were established: 1)conventional application of chemical fertilizer NPK : (N 0.96 g、P2O5 0.96 g、K2O 0.76 g); 2) low level (25%) CD1 : (N 0.72 g、P2O5 0.72 g、K2O 0.57 g) + 17.29 g organic fertilizer; 3) medium level (50%) CD2 : (N 0.48 g、P2O5 0.48 g、K2O 0.38 g) + 34.58 g organic fertilizer; 4) high level (75%) CD3 : (N 0.24 g、P2O5 0.24 g、K2O 0.19 g) + 51.86 g organic fertilizer; 5) complete replacement CD4 : 69.15 g organic fertilizer; 6) No fertilizer (CK) was used as a control treatment. Prior to the experiment, the Albic soil was conditioned to mimic natural soil conditions by dry and wet al.ternation method described in reference24. Subsequently, the organic fertilizer was thoroughly mixed with the soil. On June 18, 2023, three soybean seeds were sown in each pot. No additional fertilizers were applied during the planting period, the watering amount was strictly regulated, and the other management practices maintained consistently. On September 18, 2023, we began collecting rhizosphere soil samples during the podding period of the soybean.

Sample collection

During the podding period, the whole soybean plant was removed from the test pot with a spade and placed in a pre-sterilized stainless steel tray. The roots were shaken to remove large soil particles, and the soil adhering to the soybean roots was then gently brushed off with a brush. Fibrous roots and other impurities were then filtered through a 2 mm sieve to obtain the rhizosphere soil25. The soil samples were separated into two distinct portions. One was stored in sterile tubes at -80 °C for subsequent analysis of biological properties. The other was air-dried for the analysis of its physical and chemical properties in accordance with standard methodologies.

Analysis of soil physical and chemical properties

Soil pH was measured with a pH meter for a mixture with a solid - to - liquid ratio of 1:2.5 26. Organic matter (OM) was determined using potassium dichromate method. Total nitrogen (TN) was determined using a KDN-102 C analyser27 (Shanghai, China). Total phosphorus (TP) was determined using acid-soluble molybdenum-antimony colorimetry23 (UV-2550, Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan). Total potassium (TK) was extracted using sodium carbonate and determined by flame photometry (FP6400A, Shanghai, China), as described previously28. Available potassium (AK) and available phosphorus (AP) were determined by atomic absorption spectroscopy and ascorbic acid reduction, respectively29. Hydrolyzable nitrogen (HN) was determined by standard titration. Each treatment had three replicates.

DNA extraction and PCR amplification

The total genomic deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) of the soil microbial communities was extracted via the operation instruction of the YH-soil FastPure Soil DNA Isolation Kit (Magnetic Bead) (MJYH, Shanghai, China). The extracted genomic DNA was evaluated in terms of quality, concentration, and purity through the utilisation of 1% agarose gel electrophoresis and a NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific Inc., USA). Qualified soil samples were stored at -20℃ for later use. The primer sets 338 F (5’-ACTCCTACGGGGAGGCAGCAG-3’) and 806R (5’-GGACTACHVGGGGTWTCTAAT-3’) were used to amplify the V3-V4 variable region of the 16 S rRNA gene. For fungal, ITS1f/ITS2 primer pair (ITS1f, CTTGGTCATTTAGAGGAAGTAA) and (ITS2, GCTGCGTTCTTCATCGATGC) was selected to amplify the ITS1 region of the rRNA gene30. The variable region of gene (V3-V4) was amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using an ABI GeneAmp® 9700 thermocycler with the following program: initial denaturation at 95° C for 3 min; 27 cycles of denaturation at 95° C for 30s; annealing at 55° C for 30s, and extension at 72° C for 30s; concluding with a final extension at 72° C for 10 min, and then holding at 4 ° C. Subsequently, the target DNA sequences were amplified via PCR; products from three replicate samples were pooled and purified using a 2% agarose gel electrophoresis. The resulting purified products were subjected to electrophoresis and quantified using a Quantus™ Fluorometer (Promega, USA). Subsequently, these Purified amplicons were pooled in equimolar amounts and subjected to paired-end sequencing on either a MiSeq PE300 (Illumina, San Diego, USA), according to established protocols. These were carried out by Majorbio Bio-Pharm Technology Co. Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Once sequencing had been completed, the resulting raw data were deposited into the NCBI Sequence Read Archive database, where they were assigned the accession number SRA: BioProject PRJNA1161131.

High-throughput sequencing data analysis

The raw sequences were assessed for quality using the Fastp software31 version 0.19.6 and then merged by FLASH32 (version 1.2.11). UPARSE software33 (version 7.0.1090) was used to cluster the quality-controlled spliced sequences into operational taxonomic units (OTUs) and to eliminate chimeras. Sequence leveling was performed to ensure uniform sequence coverage across all samples. The taxonomy of each OTU representative sequence was analyzed by RDP classifier34 (version 2.11). This analysis was conducted using the Silva 16 S rRNA gene database (v138) with a confidence threshold of 70%. The composition and abundance of the microbial communities were determined for each sample at various taxonomic levels.

Data analysis

The data were subjected to preliminary processing using Microsoft Excel 2007. Subsequently, a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted using IBM SPSS 20.0 software35 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, United States). A number of multiple comparisons and tests of variance were conducted in accordance with Duncan’s method (α = 0.05), with a view to analysing the soil’s physicochemical properties. In addition, the Chao1, Ace, and Shannon indices were analysed to identify significant differences in microbial alpha diversity. Furthermore, the Principal Coordinates Analysis (PCoA) method, based on the Bray-Curtis distance, was used to determine the extent of differences in microbial community composition among soil samples. Venn diagrams were created using shared OTU tables derived from sparse tables. Bacterial taxa with significant differences in abundance at the phylum, genus levels between the several treatments were identified using the Linear Discriminant Analysis Effect Size (LEfSe) method36. The LEfSe analysis, with visualization facilitated by the Galaxy Version 1.0, was conducted with a LDA score of > 4.0 and a P-value of < 0.05. A redundancy analysis (RDA) was conducted using Canoco 5 software37 to examine the relationship between species at the phylum level of soil samples and soil chemical properties. Correlations among the top 200 OTUs were calculated using the Spearman correlation coefficient. The OTUs with correlation coefficients of r ≥ 0.6 and p < 0.01 were selected for the construction of soil bacterial and fungi correlation network diagrams utilising Gephi (version 9.2)38. The correlation graphs were generated using GraphPad Prism 9, SigmaPlot 12.0, R language version 3.3.1, and Adobe Illustrator v29.3.

Results

Rhizosphere soil nutrients

Table 1 illustrates the impact of disparate fertilisation techniques on rhizosphere soil nutrients. Significant differences were observed in the effects of different fertilisation measures on rhizosphere soil nutrients (P < 0.05). Compared with the control (CK), all fertilization treatments significantly increased rhizosphere soil pH and nutrient levels, including organic matter (OM), Total potassium (TK), Total phosphorus (TP), Total nitrogen (TN), Available potassium (AK), Available phosphorus (AP), and Hydrolyzable nitrogen (HN). As the proportion of organic fertilizers in use has increased, there has been an initial rise in rhizosphere soil pH, OM, TN, TP, and HN, which has subsequently declined. The highest values were observed in the CD3 treatment, with a pH of 6.26, OM content of 36.23 g/kg, TN of 1.58 g/kg, TP of 0.81 g/kg, and AN of 160 mg/kg. Compared to NPK trial, soil pH, OM, TP, AP and HN in CD3 exhibited a marked increase by 4.33%, 18.67%, 20.90%, 23.35% and 32.97%, respectively. The results demonstrate that the application of high levels (75%) of organic fertilizer in place of chemical fertilizer can enhance the rhizosphere soil nutrient content in Albic soil crops and mitigate soil acid-base imbalances.

Rhizosphere soil microbial diversitys

Diversity data were analyzed for 18 soil samples. The 16 S rRNA and ITS gene sequencing results yielded a total of 1,126,615 and 1,191,087 valid sequences, respectively. After OTU clustering at 97% similarity, bacteria yielded a total of 1,087,621 optimized sequences, comprising 452,900,350 bases with an average sequence length of 416 bp; fungi yielded a total of 1,132,889 optimized sequences, comprising 282,519,897 bases with an average sequence length of 249 bp. The sequencing saturation and depth for all samples satisfied the experimental requirements.

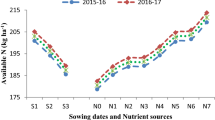

The Shannon, Ace, and Chao1 indices were employed to evaluate the impact of disparate fertilisation treatments on microbial diversity in rhizosphere soil. The findings demonstrated that the implementation of fertilisation techniques resulted in a notable impact on the diversity of bacterial and fungi communities (P < 0.05). High levels of organic fertilizer replacing chemical fertilizer treatments significantly increased bacterial diversity and richness but decreased fungi diversity and richness. In particular, the bacterial ACE and Chao1 indices of CD1, CD2, and CD3 treatments were greater than those in NPK, And CD3 treatment had the significant increase of ACE and Chao indices by 19.49% and 21.02%, respectively (Fig. 1 C and E). Meanwhile, the Shannon index was significantly increased by 3.38% in CD3 only. (Fig. 1 A). For fungi, however, the Shannon, ACE, and Chao1 indices of the CD3 treatment were significantly lower than those of the NPK treatment by 15.53%, 34.05%, and 32.43%, respectively (Fig. 1B、D and F).

Shannon index (A, B), ACE index (C, D) and Chao 1 index (E, F), bacteria and fungi, and PCoA analysis based on Anosim intergroup difference test (G. bacteria and H. fungi) for different fertilization treatments. Data are means ± SE (n = 3). Different letters indicate significant differences (P < 0.05) according to ANOVA.CK: no fertilizer application (CK); NPK: Conventional fertilization; CD1, CD2 and CD3 are 25%, 50 and 75% treatments of organic fertilizers replacing chemical fertilizers; CD4 is 100% organic fertilizer replacing chemical fertilizers.

The results of PCoA demonstrated that there were significant differences in the bacterial and fungi communities between the six treatments (P = 0.001). The rhizosphere soil bacterial and fungi communities of the NPK, CD1, and CD2 treatments exhibited greater similarity, while those of the CD3, CD4, and CK treatments were more distinct from the others. The bacterial and fungi communities in CD3 treatment showing a clear separation trend from those in NPK treatment. It indicates that fertilization measures can change the rhizosphere soil bacterial and fungi community structure. And replacing chemical fertilizer with high ratio of organic fertilizer has a particularly significant effect (Fig. 1G and H).

Rhizosphere soil microbial community composition and structure

Cluster analysis was performed using the USEARCH-uparse algorithm with 97% OTU sequence similarity and 0.7 classification confidence. The SILVA 138/16S_Bacteria database was used for bacterial classification, and the UNITE 8.0/ITS_Fungi database was used for fungi species classification, with sequences from one or more samples grouped together based on these criteria. As shown in figure. S1, the six treatments shared 1788 OTUs for rhizosphere soil bacteria and 227 OTUs for fungi. Bacterial OTU numbers were in the order of CD3 > CD4 > CD2 > CD1 > NPK > CK. And fungi OTU numbers followed the order of CD2 > NPK > CD3 > CD4 > CD1 > CK. The annotation results showed that bacterial OTUs belonged to 41 phyla, 142 orders, 566 families, and 1112 genera, while fungi OTUs belonged to 14 phyla, 53 orders, 116 families, and 496 genera.

To investigate the impact of replacing chemical fertilizer with organic fertilizer on rhizosphere soil bacterial and fungi communities in soybean grown in Albic soil, comparative analyses were conducted at the phylum and genus levels. The results indicated that treatments involving organic fertilizer (CD1, CD2, CD3) influenced the abundance of soil bacteria and fungi at various taxonomic levels. At the phylum level, the top 10 dominant bacterial and fungi species in rhizosphere soil showed consistent abundance, although there were differences among specific species. Among the bacterial phyla with high relative abundance (> 5%) in all treatments were Proteobacteria (21.07–30.11%), Actinobacteriota (15.94–27.74%), Acidobacteriota (9.61–14.59%), Chloroflexi (9.58–14.59%), and Verrucomicrobiota (5.03–6.95%) (Fig. 2 A). The relative abundance of Proteobacteria exhibited a marked increase in the CD1, CD2, CD3, and CD4 treatments than in NPK, by 35.45%, 20.45%, 36.11% and 42.90%, respectively. While a decrease (as evidenced in Table S1) in the relative abundance of Acidobacteriota, Chloroflexi, and Verrucomicrobiota was observed. For fungi, Ascomycota, Basidiomycota, Mortierellomycota, k__Fungi, and Chytridiomycota were the phyla with higher relative abundance (> 5%). Compared with the control (CK), all fertilizer treatments reduced the relative abundance of Ascomycota, while the opposite was true for Basidiomycota, Mortierellomycota, and k__Fungi. The CD3 treatment had the highest relative abundance of Basidiomycota and the lowest of Ascomycota, increasing by 286.79% and decreasing by 26.28% compared to NPK, respectively (Fig. 2B and Table S2).

Bacterial and fungi community composition and structure of rhizosphere soil in different treatments. (A), (B), (C) and (D) represent the phylum and genus levels of bacteria and the phylum and genus levels of fungi, respectively. The bar chart shows the top ten species in relative abundance at the phylum level, with the rest represented by Others, and the heat map shows the top 30 species in relative abundance at the genus level, with red representing high abundance and blue representing low abundance, and the shade of the color denoting the magnitude of relative abundance.

At the genus level, various fertilization treatments influenced the relative abundance of both bacterial and fungi species in the rhizosphere soil, with fungi species exhibiting more pronounced changes. The predominant bacterial genera across treatments were g_norank_f_norank_o_Gaiellales (3.35–7.75%), g_Candidatus_Udaeobacter (4.12–5.89%), g_Sphingomonas (3.01–6.46%), and g_norank_f_norank_o_Acidobacteriales (2.49–3.94%). Notably, all fertilization treatments led to a decrease in the relative abundance of Sphingomonas, while an increase in the relative abundance of g_norank_f_norank_o_Acidobacteriales (Fig. 2 C and Table S3). Among fungi, the genera Conocybe, Mortierella, Fusarium, k__Fungi, Phoma, Schizothecium, p__Chytridiomycota, and Didymella showed higher relative abundance. Further analysis revealed that the application of organic fertilizer (CD1-CD4) specifically reduced the relative abundance of Fusarium, Phoma, and Didymella, but notably increased that of Conocybe, with the most significant increase observed in the CD3 treatment (Fig. 2D and Table S4).

Taxa enrichment differences between treatment groups were analyzed using LEfSe, with an linear discriminant analysis(LDA) threshold of > 4.0. The results indicated significant differences in enriched markers between bacteria and fungi across treatment groups, and fungi exhibited a greater number of distinct markers. The rhizosphere soil bacterial community exhibited 10 taxa with significant enrichment differences between treatments, with CK, NPK, CD1, and CD3 showing 1, 2, 3, and 4 distinct markers, respectively. Notably, the order Burkholderiales was significantly enriched exclusively in the CK treatment, with an LDA score higher than other taxonomic units (Figure. S2). The orders Sphingomonadales, Sphingomonadaceae, Sphingomonas, Anaerolineae, and SBR1031 were enriched in the CD1 and CD3 treatments, respectively (Fig. 3 A). In the fungi community, a total of 53 taxa showed significant enrichment differences, with 7 major taxa in the CK treatment predominantly belonging to the phylum Ascomycota, order Pleosporales, and genus Didymella, where the phylum Ascomycota also had the highest LDA score (Figure. S3). In the NPK treatment, the number of significantly different markers was the lowest, while CD2 and CD3 treatments had higher counts, with 15 and 11 markers, respectively. The primary enriched taxa included the order Sordariales, phylum Mortierellomycota, family Mortierellaceae, genus Mortierella, order Mortierellomycetes, and phylum Basidiomycota, order Agaricomycetes, order Agaricales, and genus Conocybe. CD4 exhibited a total of seven differentially abundant taxa, primarily within the phylum Glomeromycota and the order Tremellodendropsidales (Fig. 3B). The results indicate that the partial replacement of chemical fertilizers with organic alternatives can influence the composition of bacterial and fungi communities by modulating the abundance of specific bacterial groups.

LEfSe analysis of Rhizosphere soil bacteria (A) and fungi (B) from different fertilization treatments. Different colored areas represent different components (red for CK, blue for NPK, green for CD1, pink for CD2, purple for CD3, and orange for CD4), and the diameter of each circle is proportional to the relative abundance of the taxonomic unit, with inner to outer circles corresponding to phylum to genus levels.

Correlation between microbial community structure and environmental factors

The significant relationship between the major bacterial and fungi communities in the rhizosphere soil and soil nutrients was studied using RDA analysis. Bacterial RDA analysis revealed that the two major axes explained 34.45% and 16.20% of the variance, respectively. Specifically, TK, AK, TP, AN, and TN were positively correlated with Acidobacteriota, Myxococcota, and Firmicutes, predominantly found in the first quadrant Whereas AP, OM, and pH correlated positively with Proteobacteria, Gemmatimonadota, and Bacteroidota, mainly found in quadrant IV. Actinobacteriota showed a negative correlation with all rhizosphere soil nutrients. pH (r²= 0.4843, P = 0.005) and OM (r²= 0.4795, P = 0.009) were the primary environmental factors influencing bacterial communities (Fig. 4 A and Table S5). Fungi RDA analysis indicated that the two major axes accounted for 55.93% and 8.82% of the variance, respectively. Specifically, AN, pH, and TP were positively correlated with Basidiomycota, primarily located in the second quadrant. OM, AP, TN, TK, and AK correlated positively with Glomeromycota, Mortierellomycetes, and unclassified fungi, mainly found in the third and fourth quadrants. Conversely, Ascomycota exhibited negative correlations with all nutrients. OM (r² = 0.5708, P = 0.001) was the key environmental factor influencing fungi communities (Table S6). The findings demonstrate a notable correlation between rhizosphere soil nutrients including pH, OM, and TP, and the structure of bacterial and fungi communities (Fig. 4B). Furthermore, these findings suggest that the composition and structure of these communities may be indirectly influenced by the partial substitution of chemical fertilizers with organic ones, which could enhance rhizosphere soil nutrient levels.

Characterization of soil microbial networks under different fertilization treatments

Microbial co-occurrence networks were established to analyze the relationships between soil bacterial and fungi species under various fertilization conditions. The networks for the NPK, CD1, CD2, CD3 and CD4 treatments featured 6049, 6418, 6868, 6842, 6800 edges for bacteria, and 5614, 5397, 5297, 5470 and 4983 edges for fungi, respectively. It indicates that partial replacement of chemical fertilizers with organic ones strengthens bacterial interspecies interactions. The average degree of connectivity networks of NPK, CD1, CD2, CD3 and CD4 trails was 60.794, 64.503, 69.025, 68.420, 68.342, and 56.140, 53.970, 53.236, 54.700 for bacterial and 49.830 for fungi networks, respectively. Network densities of NPK, CD1, CD2, CD3 and CD4 trails were 0.307, 0.326, 0.349, 0.344 0.345 for bacteria, and 0.282, 0.271, 0.269, 0.275 and 0.250 for fungi, respectively (Fig. 5 A and B). Treatments with organic fertilizers consistently demonstrated higher average degrees and network densities than NPK, suggesting an increase in the intensity of bacterial interactions and a denser network structure. Conversely, the impact on fungi networks followed an opposite trend. The relative abundances of bacterial and fungi species within the co-occurrence networks varied across treatments. Proteobacteria, Acidobacteriota and Actinobacteriota exhibited a higher degree of prevalence in bacterial networks. Ascomycota was predominant in the fungi network. Although the organic fertilizer treatment simplifyied the network structure, it did not significantly alter the relative abundance of Ascomycota. The bacterial taxa composition remained consistent across treatments, yet the CD4 treatment displayed the lowest diversity of fungi taxa.

Discussion

Effect of organic fertilizer substitution on soil nutrients

The efficacy of soil nutrients in the rhizosphere, which is intimately associated with the plant root system, directly influences plant growth and the health of the soil ecosystem. Jianhong Ren et al. found that the short-term effects of partially substituting for chemical fertilizers with organic ones led to significant enhancements in nutrient accumulation, including TN, TP, and TK, corroborating the findings of our study25. In comparison to conventional fertilization methods, the partial substitution for chemical fertilizers with organic ones significantly enhanced the nutrient content in the rhizosphere, particularly affecting soil pH, OM, and AP levels. The enhancement results from the organic fertilizers’ rich content of organic matter and nutrients, which increased the soil’s initial carbon storage and nutrient content39, boosted microbial activity40, and promoted the formation of larger soil pores and a more stable structure, thereby improving the supply of nutrients to the roots41. An increase in soil organic matter content results in a greater production of organic acids, which in turn activates soil phosphorus. It enhances both the content and utilisation efficiency of AP in the soil42,43. Concurrently, substances such as bicarbonate and organic acids in manure have a buffering effect, which can balance the soil acidity and alkalinity44. Furthermore, the findings revealed that the substitution of high levels of organic fertilizers for chemical fertilizers resulted in a more pronounced impact on the overall nutrient composition of the inter-root soil in Albic soil.

Effects of organic fertilizer substitution on soil microbial diversity and composition

Soil microbial diversity is recognized as an important indicator of the diversity and stability of soil ecosystem functions, and Shannon, Ace, and Chao1 indices are widely used to evaluate soil microbial diversity, with their values reflecting diversity and richness. Our findings indicate that 75% organic fertilizer replacement of chemical fertilizer treatments resulted in a notable enhancement in soil bacterial diversity and abundance at the inter-root level when compared to conventional fertilization methods. Conversely, fungi populations exhibited no discernible changes, which can be attributed to the inherent ecological differences between bacterial and fungi niches within the soil environment, as well as their distinct adaptive responses to external changes. It is also in line with previous findings45. The input of composted cow manure provided more carbon and nutrients to the soil, which changed the soil chemical properties, such as pH, redox potential, etc. The fungi were more sensitive to the changes in the chemical environment. The growth and reproduction of certain endemic fungi were restricted due to the soil environment changes, which, leading to the reduction of the soil fungal diversity. And the RDA of this study demonstrating the negative correlation between certain fungi and soil environmental factors, also explains this phenomenon to some extent. Furthermore, our findings demonstrate that soil microbial β-diversity was markedly influenced by organic fertilizer substitution and had, notable differences in dispersion among the various treatments. It suggests that the structure and diversity of soil bacterial and fungi communities are also subject to change as a result of the combination of factors such as different agricultural management practices46, soil fertility, and pH47.

The role of soil microbial communities is of great significance to the functioning of ecosystem processes, including the decomposition of soil organic matter, the formation of humus, and the transformation and cycling of nutrients. The composition of bacterial and fungi communities is indicative of both biotransformation efficiency and soil fertility status48,49. Different fertilization practices, tillage systems, and cropping patterns can affect soil microbial community composition50. We found that partial replacement of chemical fertilizer by organic fertilizer treatments exerted an impact on the rhizosphere soil microbial community composition, predominantly as a consequence of alterations in the proportion of species present at varying taxonomic levels (phyla and genera). For instance, the bacterial phylum Proteobacteria and the fungi species Basidiomycota were significantly elevated under high levels (75%) of organic fertilizer replacement of chemical fertilizers treatment, whereas the opposite was true for the bacterial phylum Actinobacteriota and the fungi phylum Ascomycota (Tables S1 and S2). Proteobacteria are key players in the carbon and nitrogen cycles and can utilize unstable carbon due to their r-strategy, co-nutrient properties.It has been shown that Proteobacteria are better adapted to nutrient-rich environments and have a positive correlation with carbon, however, Actinobacteriota show a negative correlation51. Studies have shown that Actinobacteriota prefers soil environments with reduced carbon or nutrient availability52. Meanwhile, Basidiomycota, as decomposers, break down organic matter, and the application of organic fertilizer enriches the carbon and nutrient sources, creating a more conducive environment for their growth and reproduction. While Ascomycota phylum showed negative correlation with soil carbon and nutrients. hence, the high level of organic fertilizer replacing chemical fertilizer has different effects on different species of soil bacteria and fungi. A multilevel species discrimination analysis demonstrated notable distinctions in the bacterial and fungi communities between the various fertilizer treatments. Soil bacteria and fungi play different roles in the ecosystem and therefore respond differently to changes in soil chemical conditions. Fungi communities may contain more specialized or environmentally condition-specific taxa, making them more indicative of environmental changes.

Microbial correlation with environmental factors

The composition of rhizosphere soil bacterial and fungi communities is closely associated with soil physicochemical factors. The results of the RDA analysis indicated a positive correlation between the bacterial phylum Proteobacteria and the fungi phylum Basidiomycota and nutrient elements, including pH, OM, and AP, while Actinobacteriota and Ascomycota were negatively correlated with the rhizosphere soil nutrients. This correlation also partially explains the differential effects of organic fertilizer alternative to chemical fertilizer treatments on the promotion and suppression of rhizosphere soil dominant flora.It suggests that soil nutrients can directly influence microbial survival and may also indirectly affect microbial communities through changes in soil nutrients properties. Meanwhile, our findings indicated that pH and OM were the most significant factors influencing bacterial and fungi communities, respectively, and were the primary environmental drivers of the rhizosphere soil microbial communities. Yin Dawei found that pH and OM were important factors influencing soil microbial communities in their study of the effect of organic materials on nutrient and microbial composition of Albic soil, which is consistent with the findings of the present study53.

Effect of organic fertilizer substitution on soil microbial network structure

The partial replacement of chemical fertilizers with organic ones affects the structure of rhizosphere soil microbial communities in a complex, multi-dimensional ecological manner. The microbial network structure is influenced by various environmental factors and inter-species interactions. The average degree and network density are important indicators for assessing the complexity and stability of microbial networks. An increase in the average degree indicates more connections between species, suggesting a higher level of network interconnectivity. We found that the organic alternative treatment group led to significant changes in the network characteristics of soil bacterial communities. The introduction of organic fertilizers significantly enhanced bacterial interactions, as indicated by an increased average degree and network density. Such changes indicate that organic fertilizers promote synergistic interactions among bacterial species, leading to a more compact and complex network structure54. Yang Luhua found that combining organic and inorganic fertilizers enhanced the modularity and cohesion of soil and rhizosphere microbial networks, leading to more stable and complex networks14. This enhancement may be attributed to increased microbial carbon source utilization and improved soil microbial carbon use efficiency due to the partial substitution of organic for inorganic fertilizers. This optimization of the bacterial community structure, along with enhanced soil biological quality, created a more favorable environment for bacterial survival55.

However, the responses of soil bacterial and fungi network structures to the partial replacement of chemical fertilizers by organic fertilizers were distinct, with this study revealing contrasting effects on fungi networks. It may be related to the function and ecological niche of fungi in the soil ecosystem. The decrease of the average degree and density of the fungi network under organic fertilizer treatment does not imply weakened interactions between fungal species. Rather, it may indicate the response mechanism of fungal networks to environmental changes under organic fertilizer conditions, as well as adjustments in fungal community structure to new nutrient input patterns. Conversely, other studies have reported increased complexity in soil fungal networks following the organic replacement of chemical fertilizers in tea plantations56, which is contrary to the results of our study. This discrepancy could be attributed to the more significant impact of different soil types and root exudates on fungal network structure. Therefore, it can be concluded that partial replacement of chemical fertilizers with organic ones enhanced the complexity and stability of soil bacterial networks and influenced soil ecological processes by altering the structure and abundance of endemic fungal species within fungal communities.

In summary, the substitution of chemical fertilizers with organic ones significantly influenced both the physicochemical properties and the microbial composition and structure of rhizosphere soils, underscoring the complex interplay among these factors. Moreover, the partial replacement led to a more intricate bacterial network, providing valuable insights for the future stewardship of the rhizosphere soil environment in Albic soil. Although this study provides valuable insights into the effects of organic fertilizers on microbial community structure within rhizosphere soils, it is not without its limitations. Future studies should concentrate on the enduring impacts of fertilization practices on microbial diversity and functionality, and leverage multi-omics analyses to explore the dynamics between microbial communities and soil nutrient cycles. Such investigations will clarify the mechanisms by which organic fertilizers enhance soil fertility and support sustainable agricultural practices.

Conclusion

This study demonstrated that partial replacement of chemical fertilisers increased the pH and nutrient levels of Albic soils as compared to conventional fertiliser application, especially at higher concentrations of organic fertilisers, soil pH significantly increased by 4.33%, soil OM, TP, AP, and HN significantly improved nearly 20-30%. Moreover, the diversity and abundance of soil bacteria increased significantly by over 20%, while fungi showed the opposite trend. The dominant species of Proteobacteria and Basidiomycota significantly significantly increased by 36.11% and 286.79%, respectively. Soil pH and OM were identified as key factors influencing microbial composition in soybean rhizosphere soils of Albic soil. In addition to this, Organic fertiliser substitution enhanced bacterial interactions, resulting in a more complex and stable network structure. The findings of this study underscore the diverse responses of rhizosphere soil microbial communities to the incorporation of organic matter, providing a scientific framework for optimizing fertilization strategies and soil health management in Albic soil and offering actionable solutions for advancing sustainable agricultural practices.

Data availability

All the original high-throughput sequencing data in this study have been deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) database (accession number: PRJNA1161131). The data are fully accessible through the following persistent URL: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/PRJNA1161131/. Other supplementary data are provided as supplementary materials in this article.

References

Liu, Z. et al. Soil quality assessment of albic soils with different productivities for Eastern China. Soil Tillage. Res. 140, 74–81 (2014).

Yin, D. et al. Some thoughts on using Biochar to improve albic soil. Agricultural Sci. 10, 807–818 (2019).

Wang, Q., Zhang, D., Jiao, F., Zhang, H. & Guo, Z. Impacts of farming activities on carbon deposition based on fine soil subtype classification. Front. Plant. Sci. 15, 1381549 (2024).

Yang, T., Siddique, K. H. M. & Liu, K. Cropping systems in agriculture and their impact on soil Health-a review. Glob Ecol. Conserv. 23, e1118 (2020).

SONG, W. et al. Effects of Long-Term fertilization with different substitution ratios of organic fertilizer on paddy soil. Pedosphere 32, 637–648 (2022).

Li, H. et al. Nutrients available in the soil regulate the changes of soil microbial community alongside degradation of alpine meadows in the Northeast of the Qinghai-Tibet plateau. Sci. Total Environ. 792, 148363 (2021).

Xiao, X. et al. Chemical fertilizer reduction combined with Bio-Organic fertilizers increases cauliflower yield via regulation of soil biochemical properties and bacterial communities in Northwest China. Front. Microbiol. 13, 922149 (2022).

Geng, Y., Cao, G., Wang, L. & Wang, S. Effects of equal chemical fertilizer substitutions with organic manure on yield, dry matter, and nitrogen uptake of spring maize and soil nitrogen distribution. Plos One. 14, e219512 (2019).

Wu, L. et al. Fertilization effects on microbial community composition and aggregate formation in Saline-Alkaline soil. Plant. Soil. 463, 523–535 (2021).

Dai, X. et al. Partial substitution of chemical nitrogen with organic nitrogen improves rice yield, soil biochemical indictors and microbial composition in a double rice cropping system in South China. Soil Tillage. Res. 205, 104753 (2021).

Li, X. et al. Impacts of partial substitution of chemical fertilizer with organic fertilizer on soil organic carbon composition, enzyme activity, and grain yield in Wheat–Maize rotation. Life 13, 1929 (2023).

Wei, Z. et al. Substitution of mineral fertilizer with organic fertilizer in maize systems: A Meta-Analysis of reduced nitrogen and carbon emissions. Agronomy 10, 1149 (2020).

NING, C. et al. Impacts of chemical fertilizer reduction and organic amendments supplementation on soil nutrient, enzyme activity and heavy metal content. J. Integr. Agric. 16, 1819–1831 (2017).

Yang, L. et al. Combined organic-Inorganic fertilization builds higher stability of soil and root microbial networks than exclusive mineral or organic fertilization. Soil. Ecol. Lett. 5, 220142 (2023).

Li, J. et al. Soil Aggregate-Associated organic carbon mineralization and its driving factors in rhizosphere soil. Soil Biol. Biochem. 186, 109182 (2023).

Smalla, G. B. K. Plant species and soil type cooperativelyshape the structureand functionof microbial communities in the rhizosphere. Fems Microbiol. Ecol. 1, 1–13 (2009).

Shen, J. et al. Maximizing root/rhizosphere efficiency to improve crop productivity and nutrient use efficiency in intensive agriculture of China. J. Exp. Bot. 64, 1181–1192 (2013).

Liu, B. et al. Partially replacing chemical fertilizer with manure improves soil quality and ecosystem multifunctionality in a tea plantation. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 378, 109284 (2025).

Chen, W., Zhang, X., Hu, Y. & Zhao, Y. Effects of Different Proportions of Organic Fertilizer in Place of Chemical Fertilizer On Microbial Diversity and Community Structure of Pineapple Rhizosphere Soil. Agronomy. 14, 59 (2024).

Wang, J. et al. Synergistic effects of rhizosphere effect and combined organic and chemical fertilizers application on soil bacterial diversity and community structure in oilseed rape cultivation. Front. Microbiol. 15, 1374199 (2024).

Lu, Z. et al. Effects of partial substitution of chemical fertilizer with organic manure on the activity of enzyme and soil bacterial communities in the mountain red soil. Front. Microbiol. 14, 1234909 (2023).

Li, M. et al. Effects of Biochar amendment and organic fertilizer on microbial communities in the rhizosphere soil of wheat in yellow river delta Saline-Alkaline soil. Front. Microbiol. 14, 1250453 (2023).

Gong, X. et al. Responses of rhizosphere soil properties, enzyme activities and microbial diversity to intercropping patterns on the loess plateau of China. Soil Tillage. Res. 195, 104355 (2019).

Xiu, L. et al. Biochar can improve biological nitrogen fixation by altering the root growth strategy of soybean in albic soil. Sci. Total Environ. 773, 144564 (2021).

Ren, J. et al. Rhizosphere soil properties, microbial community, and enzyme activities: Short-Term responses to partial substitution of chemical fertilizer with organic manure. J. Environ. Manage. 299, 113650 (2021).

Ge, G. et al. Soil biological activity and their seasonal variations in response to Long-Term application of organic and inorganic fertilizers. Plant. Soil. 326, 31–44 (2010).

Bremner, J. M., Breitenbeck, G. A. & Selskostopanska Akademiya, S. B. A simple method for determination of ammonium in Semimicro-Kjeldahl analysis of soils and plant materials using a block digester. Commun. Soil. Sci. Plant. Anal. 14, 905–913 (1983).

Wu, Y. et al. Variations in the diversity of the soil microbial community and structure under various categories of degraded wetland in Sanjiang plain, Northeastern China. Land. Degrad. Dev. 32, 2143–2156 (2021).

Chen, J. et al. Shifts in soil microbial community, soil enzymes and crop yield under peanut/maize intercropping with reduced nitrogen levels. Appl. Soil. Ecol. 124, 327–334 (2018).

Li, W., Li, H., Liu, Y., Zheng, P. & Shapleigh, J. P. Salinity-Aided selection of progressive onset denitrifiers as a means of providing nitrite for anammox. Environ. Sci. Technol. 52, 10665–10672 (2018).

Chen, S., Zhou, Y., Chen, Y. & Gu, J. Fastp: an Ultra-Fast All-in-One Fastq preprocessor. Bioinformatics 34, i884–i890 (2018).

Magoč, T., Salzberg, S. L. & Flash Fast length adjustment of short reads to improve genome assemblies. Bioinformatics 27, 2957–2963 (2011).

Edgar, R. C. & Uparse Highly accurate Otu sequences from microbial amplicon reads. Nat. Methods. 10, 996–998 (2013).

Wang, Q., Garrity, G. M., Tiedje, J. M. & Cole, J. R. NaïVe bayesian classifier for rapid assignment of Rrna sequences into the new bacterial taxonomy. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73, 5261–5267 (2007).

Shi, Y. et al. Chemical fertilizer reduction combined with organic fertilizer affects the soil microbial community and diversity and yield of cotton. Front. Microbiol. 14, 1295722 (2023).

Segata, N. et al. Metagenomic biomarker discovery and explanation. Genome Biol. 12, R60 (2011).

Dalu, T. et al. Effects of environmental variables on Littoral macroinvertebrate community assemblages in subtropical reservoirs. Chem. Ecol. 37, 419–436 (2021).

Tang, H. et al. Effects of different Long-Term fertilization on rhizosphere soil nitrogen mineralization and microbial community composition under the Double-Cropping rice field. Archiv Für Acker- Und Pflanzenbau Und Bodenkunde. 70, 1–16 (2024).

Wang, J. L. et al. Balanced fertilization over four decades has sustained soil microbial communities and improved soil fertility and rice productivity in red paddy soil. Sci. Total Environ. 793, 148664 (2021).

Luan, H. et al. Substitution of manure for chemical fertilizer affects soil microbial community diversity, structure and function in greenhouse vegetable production systems. Plos One. 15, e214041 (2020).

Ye, G. et al. Manure over crop residues increases soil organic matter but decreases microbial necromass relative contribution in upland Ultisols: results of a 27-Year field experiment. Soil Biol. Biochem. 134, 15–24 (2019).

Xin, X. et al. Yield, phosphorus use efficiency and balance response to substituting Long-Term chemical fertilizer use with organic manure in a Wheat-Maize system. Field Crops Res. 208, 27–33 (2017).

Alori, E. T., Glick, B. R. & Babalola, O. O. Microbial phosphorus solubilization and its potential for use in sustainable agriculture. Front. Microbiol. 8, 971 (2017).

Gao, J. et al. Changes in soil fertility under partial organic substitution of chemical fertilizer: A 33-Year trial. J. Sci. Food Agric. 103, 7424–7433 (2023).

Jin, N. et al. Reduced chemical fertilizer combined with Bio-Organic fertilizer affects the soil microbial community and yield and quality of lettuce. Front. Microbiol. 13, 863325 (2022).

Zhou, J. & Fong, J. J. Strong agricultural management effects on soil microbial community in a Non-Experimental agroecosystem. Appl. Soil. Ecol. 165, 103970 (2021).

Rousk, J. et al. Soil bacterial and fungal communities across a ph gradient in an arable soil. ISME J. 4, 1340–1351 (2010).

Manasa, M. R. K. et al. Role of Biochar and organic substrates in enhancing the functional characteristics and microbial community in a saline soil. J. Environ. Manage. 269, 110737 (2020).

Moreira, H., Pereira, S. I. A., Vega, A., Castro, P. M. L. & Marques, A. P. G. C. Synergistic effects of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and plant growth-Promoting bacteria benefit maize growth under increasing soil salinity. J. Environ. Manage. 257, 109982 (2020).

Montiel-Rozas, M. M. et al. Long-Term effects of organic amendments on bacterial and fungal communities in a degraded mediterranean soil. Geoderma 332, 20–28 (2018).

Waring, B. G., Averill, C. & Hawkes, C. V. Differences in fungal and bacterial physiology alter soil carbon and nitrogen cycling: insights from Meta-Analysis and theoretical models. Ecol. Lett. 16, 887–894 (2013).

Zhao, Y. et al. Variation of rhizosphere microbial community in continuous Mono-Maize seed production. Sci. Rep. 11, 1544 (2021).

Yin, D. et al. Impact of different biochars on microbial community structure in the rhizospheric soil of rice grown in albic soil. Molecules 26, 4783 (2021).

Zhang, M. et al. The stronger impact of inorganic nitrogen fertilization on soil bacterial community than organic fertilization in Short-Term condition. Geoderma 382, 114752 (2021).

Liu, X. et al. Moderate organic fertilizer substitution for partial chemical fertilizer improved soil microbial carbon source utilization and bacterial community composition in Rain-Fed wheat fields: current year. Front. Microbiol. 14, 1190052 (2023).

Ji, L. et al. Effect of organic substitution rates on soil quality and fungal community composition in a tea plantation with Long-Term fertilization. Biol. Fertil. Soils. 56, 633–646 (2020).

Funding

Heilongjiang Province Agricultural Science and Technology Innovation Project Grant Number: CX23GG08.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to this study’s conception and design.“Conceptualization, methodology and validation, X.P, Q.W.and H Y; software, B.Z. and J Y; formal analysis, Y.G.; data curation, N.Z., H D. and F L; Funding acquisition, J L; The first draft of this manuscript was written by X.P., and all authors commented on the previous versions of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pan, X., Yu, Hj., Zhang, B. et al. Effects of organic fertilizer replacement on the microbial community structure in the rhizosphere soil of soybeans in albic soil. Sci Rep 15, 12271 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96463-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96463-z

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Deciphering the influence of fertilization systems on the Allium ampeloprasum rhizosphere microbial diversity and community structure through a shotgun metagenomics profiling approach

Environmental Microbiome (2025)

-

Optimizing water and organic fertilizer use to enhance seedling growth and soil health in Chinese cabbage (Brassica rapa spp. pekinensis) cultivation

BMC Plant Biology (2025)