Abstract

We investigated the post-seismic period of the March 2021 Damasi-Tyrnavos (Thessaly, Greece) normal fault earthquakes by applying the multi-temporal interferometric Small Baseline Subset method. We processed 68 ascending Sentinel-1 acquisitions between 2020/03/15 and 2022/09/12. Our results identified three areas on the hanging wall of the ruptured faults showing non-linear deformation trends (systematic motion away from the satellite), and another area, on the footwall (systematic motion towards the satellite), interpreted as due to a post-seismic effect. Inversion of the InSAR data indicated the occurrence of afterslip co-planar to the sequence’s two largest fault planes (M 6.3 and M 6.0, respectively). Most of the afterslip, with a peak of about 0.2 m, occurred on the fault corresponding to the 4 March 2021 event, at a depth of 7.5 km, while the fault corresponding to the M 6.3 event only showed very shallow adjustments and minor features at the border of the coseismic pattern. The transient uplift affected the footwall of the 3 March 2021 event and may indicate that the rupture nearly reached the surface towards the SW of the epicenter. The afterslip showed a fast phase lasting between March and August 2021 (5 months) and a second phase from March 2022 up to September 2022. A correlation between afterslip and relocated hypocenters indicates that most of the afterslip was aseismic. The moment release of the afterslip (fast phase) is about 7% that of the mainshocks.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Crustal deformation represents a very important geophysical observable that is measured or estimated from Earth Observation data. Starting from the last decades of the 20th century, thanks to the fast technological improvements of geodetic networks and data processing methods, the number and accuracy of crustal deformation observations in different tectonic contexts have begun to increase steadily. After an earthquake, the post-seismic phase is one of the main processes acting in the crustal volume surrounding an active fault. In this interval, lasting up to several years or even more1,2,3,4, the stress modifications due to the earthquake are relaxed, generating crustal and lithospheric deformation showing significant ground movement rates 5 The post-seismic deformation is mainly concentrated near the main rupture and exhibits a logarithmic decay pattern in the temporal domain. Post-seismic deformation transients are typically generated by different processes, such as fault after-slip, poroelastic rebound, or, at a larger scale, viscoelastic relaxation of the lower crust and the upper mantle 6,7.

InSAR (Interferometric Synthetic Aperture Radar) technique can precisely measure surface deformation in the line-of-sight (LOS) direction and is thus frequently used to detect ground motion. In the last 20 years, time-series InSAR has been widely used to investigate the post-seismic deformation of events of different magnitude and rupture kinematics, such as the Mw 7.2 Landers in 1992 8, the Mw 7.1 Hector Mine event in 1999, the Mw 7.6 Izmit event in 1999 9,10, the Mw 7.9 Denali event in 2002 6,11, the Mw 6.3 L’Aquila event 5,12 and the Samos Mw 7.0 event in 2020 13. Time-series InSAR methodologies, such as PS-InSAR 14,15 (Persistent Scatterer InSAR), SBAS-InSAR 16 (Small Baseline Subset) can reduce the undesired contributions of atmospheric and topographic residuals as well as temporal coherence loss, hence providing fundamental technological support for the continuous monitoring of surface deformations following an earthquake.

Thanks to the increased number and temporal sampling of InSAR data and their processing methods, new observations of long-term and short-term deformation transients have been obtained for the post-seismic period 13,17,18,19,20,21,22. The enhanced capacities provided by improved InSAR data and techniques for monitoring crustal deformation transients are of great importance for investigating the processes related to an earthquake. The development of multi-temporal InSAR (MT-InSAR) techniques allowed the generation of a time series of deformation, providing a precise separation of the actual co-seismic displacement from the post-seismic one 23.

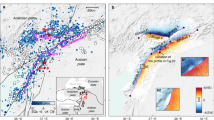

Our research aims to analyze the post-seismic stage of deformation that occurred subsequently to the March 2021 seismic sequence in Northern Thessaly, Greece (Fig. 1). The sequence started on March 3, 2021 at 10:16 UTC with a shallow earthquake of M 6.3 followed by an M 6.0 event on the next day (March 4, 2021 at 18:38 UTC). Both events were located at 20 to 30 km WNW of Larissa city, near the village Damasi 24,25,26,27 (Fig. 1). While most studies considered the co-seismic deformation field, only a few studied the post-seismic deformation 28. In this work, the post-seismic phase of the 2021 earthquakes was analyzed by using MT-InSAR techniques to detect and exploit the possible ground deformation patterns resulting from the earthquakes.

Our first main product includes the retrieved outcome from the MT-InSAR analysis which is the well-resolved spatiotemporal distribution of the surface deformation. Secondly, we used the InSAR product as input to examine the mechanism of the post-seismic deformation and locate the candidate sources aiming at obtaining the fault models for the 2021 post-seismic period. The kinematic slip inversion method was based on the Okada homogeneous elastic half-space rectangular dislocation model 29. Finally, we analyzed the temporal pattern of the geodetic data to define periods of post-seismic deformation and its relation to possible mechanisms of initiation (i.e., possible afterslip along the seismic faults) and evolution with time.

Tectonic setting

Northern Thessaly is dominated by normal faults, which began forming during the Plio-Pleistocene, as a consequence of the N-S extension, which affected the whole Aegean region 34. Geological and tectonic information of the broader study area point out the occurrence of many small to moderate length faults and a few major active faults (or series of fault segments) affecting this region of Thessaly, the so-called “Omolio” “Rodia”, “Tyrnavos”, “Elassona” and “Larissa” Faults 25,35 (Fig. 1). This set of neotectonic structures comprises a general WNW-ESE trend of normal fault segments, showing paleoseismic evidence of Late Quaternary activity 36,37.

The geology of Thessaly consists of Palaeozoic - Mesozoic basement (mostly carbonate rocks and schists) and clastic sedimentary rocks that were deposited in Neogene-Quaternary times when extensional tectonics prevailed. The sedimentary successions mainly comprise marls of the Pliocene age and terrestrial sands and gravels of the Pleistocene age, with silt to silty clay intercalations. The repeated alternations of permeable coarse-grained deposits (aquifers) with impermeable to low permeability strata (aquitards) created many successive semi-confined to confined aquifers. These compressible units may be responsible for subsidence phenomena in both urban and agricultural areas around Thessaly 38,39.

During the second half of the 20th century, Thessaly and the broader area of northern Greece experienced a series of strong earthquakes 26,30,40,41,42,43 (6.1 ≤ Mw ≤ 7.0), which caused damage to a large number of localities and all its major towns. It is therefore characterized as an area of moderate-to-high seismicity. Low-to-moderate seismic activity was also observed in the 19th century and there are a few sources reporting earthquakes in the area even in the previous centuries 30,44. The latest event before the 2021 sequence was the June 9, 2003 (07:06 UTC), Gonnoi earthquake (Mw 5.2 NOA) that stroke a mountainous region located about 20 km north of Tyrnavos 31 (Fig. 1). Dozens of buildings in the area of southern (or lower) Mt Olympus were damaged and the shock was felt throughout Thessaly, central and western Macedonia, Thessaloniki and the Sporades islands. No victims were reported. The macro-seismic intensity was assessed at 6/7 EMS-98.

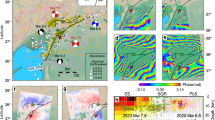

In March 2021 a sequence of three strong shallow earthquakes occurred in the semi-mountainous region west of Tyrnavos (Fig. 2) over which no records of large instrumental events existed 25,26. Bedrock geology mainly comprises marbles towards the east and gneisses-schists (to the west; Fig. 2). The focal mechanisms indicated rupture of NW-SE oriented normal faults (Fig. 2) with an M 6.3 event occurring on March 3, 2021 at 10:16 UTC, followed by an aftershock M 5.2 at 11:45 UTC, and then a second main shock M 6.1 event on March 4, at 8:38 UTC, followed by a third M5.5 event on March 12,2021 at 12:57 UTC. Field data provided no evidence for surface ruptures 25 which is in agreement with the scarcity of large, post-glacial fault scarps in this area of North Thessaly. The earthquakes mainly impacted low-rise domestic masonry buildings, while the more modern reinforced concrete structures built following the recent seismic regulations were almost unaffected 45.

The earthquakes ruptured three blind, unknown and unmapped normal fault segments with magnitudes ranging from M 6.3 (first event on March 3, 2021) to M 5.5 (third event on March 12, 2021)24,25,26,28,43,46,47,48,49,50. The activation of a north-dipping normal fault during the M 6.3 event was agreed upon by all groups that studied this sequence so far. The geometry and kinematics of the other two events are still debated in terms of the dip direction, planarity or convexity and strike of the seismic faults. Based on our geodetic data inversion modeling of these events 25,27,28,43,51,52 we concluded that the two larger events of the sequence (3 & 4 March 2021) ruptured northeast-dipping, planar faults. The faults are separate segments, 10–15 km long, they are not linked and seem to accumulate strain at low rates, because they did not emerge at the surface. Their activation within 32 h is most probably due to a mechanism of static stress transfer at mid-crustal levels (8–10 km) that was triggered by the occurrence of the Mw 6.3 earthquake on the 3rd of March 2021 25,26,43. A high Vp/Vs volume was mapped at 4–8 km depths aligned NW-SE 53 that hosted most of the aftershock sequence.

The tectonic setting of the 2021 Tyrnavos seismic sequence occurred in the Thessaly region (Northern Greece). The focal mechanisms of the three mainshocks (and the M5.2 aftershock of March 3, 2021, 11:45 UTC) and the major mapped faults are also shown. Figure generated with QGIS (https://qgis.org/) version 3.34.13.

Results

InSAR post-seismic deformation

We investigated the post-seismic period by applying the multi-temporal interferometric method named Small Baseline Subset 16 (SBAS) to identify possible non-linear deformation trends, such as the expected post-seismic (transient) effect. We processed 68 ascending Sentinel-1 acquisitions from 2021/03/15 to 2022/09/12, resulting in 230 interferometric pairs to study the ground deformation. To analyze the retrieved InSAR results, we selected three areas of interest according to the main deformation patterns (see encircled areas in Fig. 3) to better investigate the post-seismic phase.

Post-seismic mean ground velocity map, from Sentinel-1 data, along ascending orbit (Track 102). The timespan of analyzed data is from 2021/03/15 to 2022/09/12. The figure also indicates the location of the GNSS station (KLOK; see Fig. S1 for time series), the three areas considered for the time series plots shown in Fig. 4, and the trace of the modeled fault. Figure generated with QGIS (https://qgis.org/) version 3.34.13.

The map shows two main patterns characterized by two different deformation trends: a region showing movement towards the satellite (blue-cyan pixels) and a region with an opposite behavior (red-orange pixels; areas-1–2-3 in Fig. 3). These areas have a pattern similar to the co-seismic deformation field of the Mw 6.3 main event (see Fig. S2-S3 in the Supplementary Material), i.e. with an upward motion of the fault footwall and a downward movement of the hanging wall. The average rates of motion reach about + 30 mm/yr and − 30 mm/yr respectively. Figure 3 also shows downward ground movements in a region located northwest for these main patterns. This negative mean velocity pattern is likely related to the occurrence of the M 5.5 shock dated 12 March 2021 which was characterized by a shallow centroid depth of 3 km 27or 3.7 km 28. To reduce the noise, we averaged the displacement time series for all the pixels included within such areas (Fig. 4) using their arithmetic means along the date of acquisition.

Averaged post-seismic displacement time series relative to the three considered areas (see Fig. 3 for location) bottom panel) same as the top but with the periods of fast and slow decay highlighted. Figure generated with Microsoft Excel version 2502.

The averaged displacement time series highlights a clear post-seismic exponential decreasing trend (i.e., logarithmic slip along downdip) up to about mid-August 2021 especially for areas 1 and, 2 reaching about 1 ± 0.2 cm (or 0.07 mm/day), then a short period of very small displacement is still present up to early 2022. We define this fast decay rate as the first phase of the deformation. Then, from January 2022 a linear decreasing trend (motion away from the sensor) is shown up to 2 cm of ground motion (second phase with a lower rate; 0.04 mm/day) and then resuming the same behavior, affecting all 3 areas. Hence, we can assume that the fast post-seismic phase lasted no more than about 5 months starting from the occurrence of the three main events, then the motion relaxed, and finally a second phase started in January 2022 that lasted about 8 months. We confirmed this interpretation by a piecewise linear regression analysis of the time series (see methods and Fig. S9; overall R-squared of the fit is 0.977). In area A, the first breakpoint appears on May 5, 2021, where the displacement rate drops from − 48 mm/yr to 21 mm/yr, followed by a second breakpoint on August 3, 2021. In area 2 the first breakpoint appeared on July 14, 2021 (rate from − 24 mm/yr drops to + 3 mm/yr). In area 3 the first breakpoint appeared on June 24, 2021, followed very quickly by the 2nd breakpoint on July 14, 2021. Given the overall uncertainties, we suggest that the first phase of the post-seismic deformation ended mid-July to early August 2021.

Another component of the mapped ground displacement is motion towards the satellite (i.e. uplift; Fig. 5). We demonstrate cumulative post-seismic uplift of the order of 1.5 cm (Fig. 4) that lasted for about 300 days after the mainshock (or 0.05 mm/day assuming steady-state uplift). The orientation of the uplifted ground surface is NW-SE, i.e. parallel to the strike of the March 3, 2021, seismic fault and it occurs on the Zarko mountain where a set of co-seismic fractures was mapped 25. The small amount of uplift in absolute terms is comparable to that found after the Samos M 7.0 normal faulting earthquake 13. The area of uplift is about 10 km by 3 km and gets wider towards the NW, most probably because of the occurrence of the March 4, 2021 event at 9.3 km to the NW of March 3, 2021 (Fig. 2). The occurrence of a 10 km long zone of uplift at the footwall of the 1st mainshock may suggest that the rupture nearly reached the ground surface at the Zarko Mountain, thus highlighting the structural complexity of the source.

(Top) Post-seismic mean ground velocity map, from Sentinel-1 data, highlights the uplift area (blueish colors). The timespan of analyzed data is from 2021/03/15 to 2022/09/12. Bottom) the averaged time series plot. Figure generated with QGIS (https://qgis.org/) version 3.34.13 & Microsoft Excel version 2502.

Inversion method and post-seismic slip rate distribution

To derive the nature of the displacement patterns detected with the time series, we first investigated the possibility that some afterslip occurred over the fault planes that generated the coseismic deformations of the 2021 sequence51. We therefore exploited the shear dislocation in an elastic half-space model29 to get the after-slip distribution, adopting the approach to explain the post-seismic pattern of the 1999 Athens earthquake23, also retrieved by InSAR time-series.

Though the SBAS method tends to linearize the three intervals, due to the linear model assumption implemented in the software, we still observe the typical post-seismic deformation evolution characterized by a steep trend soon after the event flattening after about 5 months. Fluctuations from theoretical (logarithmic) behavior may be attributed to fault plane heterogeneity, fluid circulation, and data uncertainties.

We run the data modeling with a consolidated two-step approach, with a non-linear optimization to infer the uniform slip source followed by a linear inversion to get the slip distribution over that plane 54. To prepare the point-vector data for the inversion, we developed ad hoc procedures to handle the output of the SBAS processing, already produced in a point-vector shapefile, but with an extremely high number of observations: more than 1 million.

Moreover, the SBAS output contains as attributes the whole evolution in time of the displacement, while modeling must be carried out over a single value of static displacement, for each point. We firstly reduced the number of points by averaging them to a nearly regular mesh of 150 m, calculating also the spatial mean value for all the attributes. With this preprocessing task, and by narrowing the region of interest, we managed to reduce the number of points to the model to about 32.000. As already observed, InSAR time series shows a displacement evolution along all the considered temporal spans, with a slightly stable interval occurring during August 2021. Hence, we decided to run two different models: a first one involving only the strictly post-seismic period before the steady phase and a second including the whole time-series period. In the first case, we modeled the cumulative displacement from March 15 to August 24, 2021; in the second case, reported in the Supplementary Material (Fig. S3), modeling involves the whole period from March 2021 to September 2022. For the non-linear inversion modeling, we fixed the strike, dip, and rake angles: 312°, 40° and − 90° for the southern source, of the March 3, 2021, M 6.3 event, and 290°, 43° and − 108° for the northern source, corresponding to the March 4, 2021, M 6.0 mainshock 51. We inferred the location, depth, dimension, and uniform slip for both sources. The retrieved sources were then extended and subdivided into patches of 1 × 1 km to obtain the slip distribution through linear inversion 55. Inversion results, slip distribution, and modeled data are shown in Fig. 6.

Results of InSAR-data inversion. First row: 3D (view to SW) and planimetric views of the distributed slip models for the post-seismic displacements referring to the March 15 - August 24, 2021 period. Fault planes are those of mainshocks of March 3, 2021, and March 4, 2021, respectively. In the second row, we show the map comparison between observed (left) and modeled (center) data, with the relative residuals (right panel). Figure generated with SARscape® (https://www.sarmap.ch/index.php/software/sarscape/) version 6.1.

The two distributions (Fig. 6) show that most of the afterslip, with a peak of about 0.2 m, occurred on the fault ruptured during the March 4, 2021 event, at a depth of 7.5 km, while the fault corresponding to the M 6.3 mainshock only shows very shallow adjustments and minor features at the border of the coseismic slip pattern. A comparison with the coseismic slip pattern is shown in Fig. 7, where it is possible to appreciate that the afterslip for the March 4, 2021 plane extends downward and around the coseismic asperity. The comparison between observed and modeled data shows a generally good fit, supporting the robustness of the modeling findings; high residuals remain at the southern edge of the March 3, 2021 fault trace (black area in Fig. 6), but they are likely due to the existence of a non-planar fault segment near the surface, as also it is indicated by the fringe pattern, at the same location, of coseismic interferograms 28,51. A large NW-SE displacement gradient on the east slopes of the Zarko mountain associated with deformation due to the March 3, 2021, M 6.3 earthquake, was also previously found 25.

The moment release of the Phase-A of the afterslip (2.41E + 17 Nm) is about 7% of the two mainshocks (combined), a rather low figure compared with other normal fault earthquakes such the Athens 1999 M 6.0 event (49%)23 but still within the range of global estimates 56. This low figure is also due to the start of our InSAR monitoring (15 March 2021) with respect to the occurrence of the two mainshocks, so we probably missed the early part (a few hours to one week) of the afterslip.

The distribution of aftershocks (Fig. 8) does not overlap the afterslip distribution regarding the March 3, 2021 rupture as most events occur on either side of the asperity or at secondary faults, North and East of the main rupture. The distribution of the aftershocks towards the NW of the first event indicates the occurrence of mostly off-fault events at depths 8–12 km, that are oriented NW-SE in agreement with Coulomb stress modeling of the static stress transfer due to the March 3, 2021 earthquake 26,51.

3D views showing the comparison between the coseismic slip distributions of Kontoes et al. (2022, left) and the afterslip retrieved in this paper (right), adopting the same fault planes that ruptured during the two mainshocks. Some afterslip has occurred in the shallower part of the 1st event, but most of it extends downward the coseismic slip along the plane of the 2nd event, with a peak of 0.2 m at a depth of about 7.5 km. Figure generated with SARscape® (https://www.sarmap.ch/index.php/software/sarscape/) version 6.1.

Overall deformation map with the 2021 aftershocks overlain (March to August; 3493 events, after Kassaras et al. 2022) and the mesh grid of the retrieved source model. Figure generated with QGIS (https://qgis.org/) version 3.34.13.

Discussion

Our geodetic data revealed a two-phase post-seismic deformation following the North Thessaly earthquakes. To better analyze the retrieved post-seismic displacement field, we compared it to a similar case study such as the L’Aquila (Central Italy) M 6.3 earthquake that occurred on 6 April 2009. The post-seismic deformation of that event was mapped using InSAR analysis processing on multiple acquisitions captured by COSMO-SkyMed (X-band) sensors 57. The source of the L’Aquila earthquake was retrieved by inverting the InSAR maps, identifying a normal fault about 16 km long and 12 km wide, dipping 47° SW 54. The obtained maximum slip was estimated at 90 cm, and the up-dip projection of the fault corresponded to the northern segment of the already-known Paganica–S. Demetrio Fault.

We rearranged the InSAR displacement data to make a comparison with the 2021 Damasi-Tyrnavos case. We took into account COSMO-SkyMed data, along the ascending orbit with a post-seismic time of about 16 months, from 12 April 2009 to 6 August 2010 with a mean ground velocity (Fig. S7 in supplementary material). We can identify two main patterns of moderate-to-high negative deformation rate (red-orange pixels), one close to the surface projection of the top of the fault, and one to the projection of the bottom of the fault 58. Among them, a relatively stable area is present. Comparing this spatial pattern with the Damasi-Tyrnavos post-seismic one, they are almost coincident. Finally, looking at the time series of the deformation we averaged some points of measurements for the hangingwall area showing the larger movement. The averaged time series highlights a clear post-seismic exponential decreasing trend lasting about 5 months, followed by a nearly stable behavior. Such a post-seismic trend appears very similar to the one obtained from our Damasi-Tyrnavos (Thessaly) analysis, as shown in Fig. 9. The similarity in the post-seismic behavior of the two normal faults (Damasi-Tyrnavos and L’Aquila) indicates that afterslip is the dominant mechanism of the post-seismic deformation with a fast period of about 5–6 months (Fig. 9).

Graph showing that the post-seismic phase of normal fault earthquakes (Damasi-Thessaly and L’Aquila) lasts about 180 days after the earthquake, then we have an almost flat trend. Grey crosses indicate the average displacement time series for the L’Aquila post-seismic phase. Figure generated with Microsoft Excel version 2502.

Using 3-D views of the fault planes of the two Damasi mainshocks and the distribution of relocated aftershocks 26 we can explore the relations between afterslip and seismicity (Fig. 10). We provide strike-parallel views (from SE and NW; Fig. 10) to visualize the aftershock distribution (formal ERH errors < 1 km for 94% of events; formal ERZ errors < 1 km for 69% of events respectively) in comparison to the afterslip patch distribution. In both images, we can see that most aftershocks are off-fault aftershocks so most afterslip is aseismic. The fault-normal view (Fig. 10 center) shows a shallow cluster of aftershocks to the top-right (i.e. NW) of the afterslip patches off the 2nd mainshock fault plane. The lack of aftershocks up-dip the 2021 ruptures also supports the aseismic uplift of the footwall area seen in Fig. 5 which reached 1.5 cm over 10 months.

A recent tomographic study 53 showed a fluid-rich environment within the carbonate rocks of the greater Tyrnavos area (see also the geological map in Fig. 2). Such a host regime could result in high pore pressures and low effective normal stresses that could favor aseismic afterslip around the asperities of the 2021 ruptures 59. It is not clear why the afterslip paused in August 2021 and restarted in March 2022. Possibly the second phase was triggered by an external factor that was able to mobilize velocity-strengthening fault patches surrounding the cos-seismic slip patches.

3-D visualization of the seismogenic volume of the Damasi – Tyrnavos (north Thessaly) 2021 earthquakes. The distribution of the aftershocks is mostly away from the afterslip patches. Most aftershocks have occurred on the footwall areas of the ruptures. The views are from the SE (left), NE (center), and NW (right panel), respectively. Figure generated with SARscape® (https://www.sarmap.ch/index.php/software/sarscape/) version 6.1.

Conclusions

We investigated the post-seismic period of the March 2021 Damasi (North Thessaly Greece) normal fault earthquakes by applying the multi-temporal interferometric method named Small Baseline Subset (SBAS) using Sentinel-1 Copernicus data. Our analysis identified three areas on the hanging wall of the March 3 and March 4 ruptured faults that showed non-linear deformation trends, and one area on the footwall block which we interpret as post-seismic (transient) effects. The inversion of the InSAR data indicated the activation of two planes that are co-planar to the sequence’s two largest fault planes (M 6.3 and M 6.0, respectively). The two slip distributions show that most of the afterslip, with a peak of about 0.2 m, occurred on the fault corresponding to the 4 March 2021 event, at a depth of 7.5 km, while the fault corresponding to the M 6.3 event only shows very shallow adjustments and minor features at the border of the coseismic slip pattern. The afterslip occurred in two phases, one fast phase (mostly aseismic) that lasted between March and August 2021 and a second phase from March 2022 up to September 2022. The transient uplift affected mostly the footwall of the 3 March 2021 event (M 6.3) and indicated that the rupture nearly reached the ground surface on Zarko mountain, implying a ramp geometry of the hosting fault.

Method

InSAR data analysis

To analyze the post-seismic phase, we employed the multi-temporal InSAR techniques to assess the spatial and temporal ground motion both before and after the earthquakes. To obtain the full spatial and temporal evolution of post-seismic deformation, this study used both the PS and SBAS approaches applied to a dataset of ascending Sentinel-1 SAR images acquired in the TOPSAR mode and freely distributed by the European Space Agency. All the resulting interferometric pairs were processed using different software (i.e., SARScape, and the SNAPPING service 60 on the Geohazards Exploitation Platform (GEP), https://geohazards-tep.eu/, see Supplementary Material Fig. S8) to perform the MT-InSAR processing chain. Then, the obtained outcomes from the PS and SBAS analysis were used to cross-validate one with the other obtaining a good agreement. Following such a comparison we decided to use only the SBAS outcomes as showing a larger spatial coverage and a temporal trend more scattered with respect to the PS one.

For the SBAS processing, we selected 68 ascending Sentinel-1 acquisitions ranging from 2021/03/15 to 2022/09/12. Firstly, all the acquisitions were imported in the format desired by the user-specific software (e.g. SARscape), and then all the images were coregistered with respect to the selected one as reference (2021/09/23). Maximum values equal to 100 m and 180 days were imposed for the normal and temporal baselines, resulting in 260 interferometric pairs (see the relative connection graph Fig. S10). To reduce the influence of hilly topography and maintain high coherence, other than to minimize the phase bias effect, we mainly endorsed short-term baseline couplings, constraining the spatial baseline to 100 m as the maximum. To remove the influence of speckle noise, a multilooking factor equal to 7 and 2 along the range and azimuth direction respectively was applied to obtain a final ground resolution of 30 m. Then, using a DEM with a resolution of 30 m (ALOS World 3D, released by Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency), simulated terrain phases are generated, and the impacts of the terrain are eliminated using differencing to make differential interferograms. The interferograms were filtered applying the Goldstein filter 61. Phase unwrapping adopted the Delauney minimum-cost flow algorithm to remove the residual orbital phase from the interferogram using quadratic polynomial fitting62. Several Ground Control Points were selected in the regions with high coherence coefficients, and far from the expected postseismic displacement field, which was used to estimate and remove the phase changes caused by orbit error, the residual topography phase, and the slope phase in the unwrapped phase, using the cubic polynomial refinement method. A linear model for the deformation velocity was considered to derive an initial deformation map, and the singular value decomposition method was applied searching for the least-squares solution for each coherent pixel, as well as to estimate the nonlinear deformation. After removing the undesired contribution due to the atmospheric delay employing double filtering in the spatial and temporal domain, the surface deformation time series and mean ground deformation velocity along the line of sight (LOS) were obtained (Fig. 3 in the main manuscript).

Data availability

The NOAFAULTs dataset is available at Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8075517 Aftershock parametric data is available here: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0264370722000023#sec0100All the GPS/GNSS data were provided from cGPS Permanent Networks, HxGn–Smart–Net Greece, NOANET, and HermesNet. SAR images are available to be freely downloaded after registration from the Copernicus Browser at the following link: https://browser.dataspace.copernicus.eu/.

References

Hearn, E. H., McClusky, S., Ergintav, S. & Reilinger, R. E. Izmit earthquake postseismic deformation and dynamics of the North Anatolian fault zone. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 114, 2008JB006026 (2009).

Tsang, L. L. H. et al. Afterslip following the 2007 Mw 8.4 Bengkulu earthquake in Sumatra loaded the 2010 Mw 7.8 Mentawai tsunami earthquake rupture zone. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth. 121, 9034–9049 (2016).

Briole, P., Ganas, A., Elias, P. & Dimitrov, D. The GPS velocity field of the Aegean. New observations, contribution of the earthquakes, crustal blocks model. Geophys. J. Int. 226, 468–492 (2021).

Hong, S. & Liu, M. Postseismic Deformation and Afterslip Evolution of the 2015 Gorkha Earthquake Constrained by InSAR and GPS Observations. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 126, e2020JB020230 (2021).

D’Agostino, N., Cheloni, D., Fornaro, G., Giuliani, R. & Reale, D. Space-time distribution of afterslip following the 2009 L’Aquila earthquake. J. Geophys. Res. -Solid Earth 117, (2012).

Pollitz, F. F. Transient rheology of the upper mantle beneath central Alaska inferred from the crustal velocity field following the 2002 Denali earthquake. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth. 110, 2005JB003672 (2005).

Barbot, S. & Fialko, Y. A unified continuum representation of post-seismic relaxation mechanisms: semi-analytic models of afterslip, poroelastic rebound and viscoelastic flow: Semi-analytic models of postseismic transient. Geophys. J. Int. 182, 1124–1140 (2010).

Massonnet, D. et al. The displacement field of the Landers earthquake mapped by radar interferometry. Nature 364, 138–142 (1993).

Burgmann, R. Deformation during the 12 November 1999 Duzce, Turkey, earthquake, from GPS and InSAR data. Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 92, 161–171 (2002).

Ergintav, S. Postseismic deformation near the Izmit earthquake (17 August 1999, M 7.5) rupture zone. Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 92, 194–207 (2002).

Biggs, J. et al. The postseismic response to the 2002 M 7.9 Denali fault earthquake: constraints from InSAR 2003–2005. Geophys. J. Int. 176, 353–367 (2009).

Reale, D. et al. Postseismic deformation monitoring with the COSMO/SKYMED constellation. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 8, 696–700 (2011).

Ganas, A. et al. Co-seismic and post-seismic deformation, field observations and fault model of the 30 October 2020 mw = 7.0 Samos earthquake, Aegean sea. Acta Geophys. 69, 999–1024 (2021).

Ferretti, A. et al. A new algorithm for processing interferometric Data-Stacks: squeesar. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 49, 3460–3470 (2011).

Hooper, A., Zebker, H., Segall, P. & Kampes, B. A new method for measuring deformation on volcanoes and other natural terrains using InSAR persistent scatterers. Geophys. Res. Lett. 31, 2004GL021737 (2004).

Berardino, P., Fornaro, G., Lanari, R. & Sansosti, E. A new algorithm for surface deformation monitoring based on small baseline differential SAR interferograms. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 40, 2375–2383 (2002).

Peltzer, G., Crampé, F., Hensley, S. & Rosen, P. Transient strain accumulation and fault interaction in the Eastern California shear zone. Geology 29, 975 (2001).

Ozawa, S. et al. Detection and monitoring of ongoing aseismic slip in the Tokai region, central Japan. Science 298, 1009–1012 (2002).

Calais, E. et al. Strain accommodation by slow slip and Dyking in a youthful continental rift, East Africa. Nature 456, 783–787 (2008).

Salvi, S. et al. Results from INSAR monitoring of the 2010–2011 New Zealand seismic sequence:EA detection and earthquake triggering. in 2012 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium 3544–3547. https://doi.org/10.1109/IGARSS.2012.6350654 (IEEE, Munich, Germany, 2012).

Tsironi, V. et al. Active shortening and aseismic slip along the cephalonia plate boundary (Paliki Peninsula, Greece): evidence from InSAR and GNSS data. Tectonophysics 884, 230400 (2024).

Mildon, Z. K. et al. Transient Aseismic Vertical Deformation Across the Steeply-Dipping Pisia‐Skinos Normal Fault (Gulf of Corinth, Greece). Tectonics 43, e2024TC008276 (2024).

Atzori, S., Manunta, M., Fornaro, G., Ganas, A. & Salvi, S. Postseismic displacement of the 1999 Athens earthquake retrieved by the Differential Interferometry by Synthetic Aperture Radar time series. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 113, JB005504 (2008).

Tolomei, C. et al. The use of interferometric synthetic aperture radar for isolating the contribution of major shocks: the case of the March 2021 thessaly, Greece, seismic sequence. Geosciences 11, 191 (2021).

Ganas, A. et al. Domino-style earthquakes along blind normal faults in Northern Thessaly (Greece): kinematic evidence from field observations, seismology, SAR interferometry and GNSS. Bull. Geol. Soc. Greece. 58, 37 (2021).

Kassaras, I. et al. Seismotectonic analysis of the 2021 Damasi-Tyrnavos (Thessaly, central Greece) earthquake sequence and implications on the stress field rotations. J. Geodyn. 150, 101898 (2022).

Vavlas, N., Fountoulakis, I., Roumelioti, Z., Evangelidis, C. P. & Kiratzi, A. Imaging the sources of the March 2021 seismic sequence in Thessaly basin (Central Greece) from kinematic slip inversion and backprojection of waveform envelopes. Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 114, 758–774 (2024).

Yang, J., Xu, C., Wen, Y. & Xu, G. Complex Coseismic and Postseismic Faulting During the 2021 Northern Thessaly (Greece) Earthquake Sequence Illuminated by InSAR Observations. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, eGL098545 (2022).

Okada, Y. Surface deformation due to shear and tensile faults in a half-space. Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 75, 1135–1154 (1985).

Ambraseys, N. N. & Jackson, J. A. Seismicity and associated strain of central Greece between 1890 and 1988. Geophys. J. Int. 101, 663–708 (1990).

Pavlides, S. et al. The Gonnoi (NE Thessaly - Greece) earthquake (June 2003, Ms = 5.5) and the neotectonic regime of Lower Olympus (in Thessaloniki, 2004).

Athanassios Ganas. NOAFAULTS KMZ layer Version 6.0. Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/ZENODO.13168947 (2024).

D’Agostino, N. et al. Active crustal deformation and rotations in the Southwestern Balkans from continuous GPS measurements. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 539, 116246 (2020).

Caputo, R. & Pavlides, S. Late cainozoic geodynamic evolution of Thessaly and surroundings (central-northern Greece). Tectonophysics 223, 339–362 (1993).

Caputo, R. Geological and structural study of the recent and active brittle deformation of the neogene-quaternary basins of Thessaly. Cent. Greece Diss Aristot -Univ Thessalon 1990 (1990).

Caputo, R., Helly, B., Pavlides, S. & Papadopoulos, G. Palaeoseismological investigation of the Tyrnavos fault (Thessaly, central Greece). Tectonophysics 394, 1–20 (2004).

Tsodoulos, I. M. et al. Middle–Late holocene earthquake history of the gyrtoni fault, central Greece: insight from optically stimulated luminescence (OSL) dating and paleoseismology. Tectonophysics 687, 14–27 (2016).

Kontogianni, V., Pytharouli, S. & Stiros, S. Ground subsidence, quaternary faults and vulnerability of utilities and transportation networks in Thessaly, Greece. Environ. Geol. 52, 1085–1095 (2007).

Argyrakis, P. et al. Anthropogenically induced subsidence in Thessaly, central Greece: new evidence from GNSS data. Nat. Hazards. 102, 179–200 (2020).

Drakos, A. G. Fault parameters of the 1980 (Mw 6.5) Volos, central Greece, earthquake from inversion of repeated leveling data. Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 91, 1673–1684 (2001).

Palyvos, N. et al. Paleoseismological investigation of the oblique-normal Ekkara ground rupture zone accompanying the M 6.7–7.0 earthquake on 30 April 1954 in Thessaly, Greece: archaeological and geochronological constraints on ground rupture recurrence. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth. 115 2009JB006374 (2010).

Kourouklas, C., Console, R., Papadimitriou, E., Murru, M. & Karakostas, V. Strong earthquakes recurrence times of the Southern Thessaly, Greece, fault system: insights from a Physics-Based simulator application. Front. Earth Sci. 9, 596854 (2021).

Papadimitriou, E. et al. The seismogenic structure of March 2021 Tyrnavos (central Greece) doublet (M W 6.3 and M W 6.0), constrained by aftershock locations and geodetic data. Geophys. J. Int. 235, 644–689 (2023).

Papazachos, B. C. & Papazachou, C. The earthquakes of Greece (Ziti, 2003).

Sarhosis, V. et al. Observations from the March 2021 Thessaly earthquakes: an earthquake engineering perspective for masonry structures. Bull. Earthq. Eng. 20, 5483–5515 (2022).

Karakostas, V. et al. The March 2021 Tyrnavos, central Greece, doublet (Μw6.3 and Mw6.0): aftershock relocation, faulting details, coseismic slip and deformation. Bull. Geol. Soc. Greece. 58, 131 (2021).

Chatzipetros, A. et al. The Northern Thessaly strong earthquakes of March 3 and 4, 2021, and their neotectonic setting. Bull. Geol. Soc. Greece. 58, 222 (2021).

Papadopoulos, G. A. et al. Seismic and geodetic imaging (DInSAR) investigation of the March 2021 strong earthquake sequence in Thessaly, central Greece. Geosciences 11, 311 (2021).

Koukouvelas, I. K. et al. The March 2021 Damasi earthquake sequence, central Greece: reactivation evidence across the Westward propagating Tyrnavos graben. Geosciences 11, 328 (2021).

Mouslopoulou, V. et al. A deeper look into the 2021 Tyrnavos earthquake sequence (TES) reveals coseismic breaching of an unrecognized Large-Scale fault relay zone in continental Greece. Tectonics 41, e2022TC007453 (2022).

Kontoes, C., Haris. & et al. Coseismic surface deformation, fault modeling, and coulomb stress changes of the March 2021 Thessaly, Greece, earthquake sequence based on InSAR and GPS data. Seismol. Res. Lett. 93, 2584–2598 (2022).

De Novellis, V., Reale, D., Adinolfi, G. M., Sansosti, E. & Convertito, V. Geodetic model of the March 2021 Thessaly seismic sequence inferred from seismological and InSAR data. Remote Sens. 13, 3410 (2021).

Napolitano, F. et al. Seismic imaging of fluid-filled inherited structures of the Northern Thessaly (Greece) seismic gap. Front. Earth Sci. 11, 1176348 (2023).

Atzori, S. et al. Finite fault inversion of DInSAR coseismic displacement of the 2009 L’Aquila earthquake (central Italy). Geophys. Res. Lett. 36, (2009).

Atzori, S. et al. InSAR full-resolution analysis of the 2017–2018 M\textgreater6 earthquakes in Mexico. Remote Sens. Environ. 234, 111461 (2019).

Churchill, R. M., Werner, M. J., Biggs, J. & Fagereng, Å. Afterslip Moment Scaling and Variability From a Global Compilation of Estimates. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 127, eJB023897 (2022).

Moro, M. et al. New insights into earthquake precursors from InSAR. Sci. Rep. 7, (2017).

Lanari, R. et al. Surface displacements associated with the L’Aquila 2009 Mw 6.3 earthquake (central Italy): new evidence from SBAS-DInSAR time series analysis. Geophys. Res. Lett. 37, (2010).

Scholz, C. H. Earthquakes and friction laws. Nature 391, 37–42 (1998).

Foumelis, M. et al. SNAPPING services on the geohazards exploitation platform for copernicus Sentinel-1 surface motion mapping. Remote Sens. 14, 6075 (2022).

Goldstein, R. M. & Werner, C. L. Radar interferogram filtering for geophysical applications. Geophys. Res. Lett. 25, 4035–4038 (1998).

Pepe, A. & Lanari, R. On the extension of the minimum cost flow algorithm for phase unwrapping of multitemporal differential SAR interferograms. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 44, 2374–2383 (2006).

Acknowledgements

We thank Riccardo Caputo, Spyros Pavlides, Ritsa Papadimitriou, Vasilis Karakostas, Ioannis Koukouvelas, Sotiris Valkaniotis and Gerassimos Papadopoulos for discussions on the geology and earthquakes of Thessaly. We thank Pierre Briole for the fruitful discussion on the GPS available stations. We also thank the NOANET (www.gein.noa.gr), HermesNet (AUTH) and HxGN/SmartNet (www.metricanet.gr) network providers for the GPS data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.T., A.G., CB, and S.A. conceptualized the research, developed the applied methodologies, and drafted the manuscript. C.B. and M.F. processed the SAR data and drafted its description in the manuscript. C.T. and C.B. collected the SAR data. S.A. performed the modeling step and drafted its description in the manuscript. A.G. collaborated on finite-fault modeling. C.T. and C.B. analyzed the GNSS data to retrieve displacement time series and drafted its description in the manuscript. C.T., A.G., C.B., and S.A. wrote the manuscript and all authors revised it.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tolomei, C., Ganas, A., Bignami, C. et al. Two phases of aseismic afterslip following the March 2021 Damasi, Greece, normal faulting earthquakes retrieved from InSAR measurements. Sci Rep 15, 12995 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96503-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96503-8