Abstract

Multi-object tracking is a challenging computer vision task that is a research hotspot in the literature. Although current one-stage methods can jointly optimize detection and appearance embedding models through an end-to-end approach, they still face major challenges. These include high computational demands, difficulty in distinguishing similar objects and poor performance in reidentifying lost objects. To overcome these challenges, we propose a lightweight multi-object tracking method to enhance tracking efficiency through the dual attention mechanism. This mechanism, on the one hand, adopts an intra-sample local attention, enabling the model to focus on discriminative regions to extract instance context, thereby effectively distinguishing similar objects. On the other hand, it employs inter-sample global attention, which captures instance-level semantic information across samples, facilitating feature interaction between objects in different frames, thus enhancing the re-identification performance for lost objects. We validated the effectiveness of the proposed method with extensive experiments on publicly available MOT and our proposed STATION datasets, achieving comparable performance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Multi-object tracking (MOT) represents a critical research area within computer vision1,2,3,4, widely applied in scenarios such as human motion analysis2,5, autonomous driving6, and intelligent surveillance systems7. The primary objective of MOT is to predict the trajectories of multiple objects within a video sequence. Despite many remarkable studies being reported in5,6,8,9,10, challenges such as identifying similar or small targets and reidentifying lost objects6,10 substantially hinder tracking performance.

Currently, prevalent tracking algorithms5,6,9,11,12, employ the tracking-by-detection (TBD) framework, considering detection and tracking as distinct tasks. As illustrated in Fig.1 (a), the detection model identifies objects using bounding boxes, while the tracking model extracts appearance embeddings and then performs data association to generate trajectories.

However, this two-stage processing method lacks end-to-end optimization and suffers from significant computational overhead. One primary limitation of the TBD framework is that the separation of target detection and tracking means that detection accuracy directly impacts tracking performance. For instance, the noise or occlusions can lead to incorrect detections, which subsequently affect tracking accuracy. Additionally, as the number of objects in an image increases, the inference time also grows because appearance embedding extraction must be performed independently for each object. Although some studies have aimed at tightly combining detection and tracking8,13, the inherent independence of the detection model has not fundamentally resolved the issue of increased detection objects leading to more time consumption.

One-stage MOT methods are gradually emerging and have garnered significant attention, as shown in Fig.1(b). For instance,13 leverage the bounding box regression and classification capabilities of an object detector to predict the position of an object in the next frame. In contrast to10 introduce an innovative concept that combines detection features and appearance embeddings within a single unified framework. Despite its effectiveness, this method has certain limitations. Firstly, it employs a relatively heavy detector based on the Darknet53 backbone14, resulting in suboptimal real-time performance. Secondly, it lacks the ability to focus on discriminative features of instances to effectively distinguish similar objects. Although15 introduce attention mechanisms to mitigate interference from irrelevant information or complex backgrounds, it is inadequate for reidentifying lost objects as it overlooks instance-level semantic relationships across samples. For instance, if an object appears in sequential frames, we can capture the contextual interactions to achieve stable tracking for the lost object.

To alleviate these limitations, we propose a one-stage lightweight multi-object tracking method, illustrated in Fig. 1 (c). Specifically, we employ the intra-sample local attention mechanism (SLAM), which enables the model’s focus on discriminative regions, thereby enhancing the recognition of similar objects. Moreover, we utilize the inter-sample global attention mechanism (SGAM), which captures instance-level semantic information across samples, thus facilitating feature interaction between objects in different frames and improving the re-identification of lost objects. To validate our method, we conducted extensive comparison and ablation experiments. In summary, the main contributions of our work are as follows:

(1) We propose a dual attention mechanism to extract discriminative context features and capture instance-level semantic information shared among samples. This method significantly enhances the recognition performance for both similar objects and lost objects.

(2) We propose the STATION dataset, designed for substation scenarios, which includes real-world challenges such as occlusion and similar objects. This dataset is intended to evaluate the model’s ability to re-identify lost objects and distinguish between similar objects.

(3) Extensive experiments on MOT and STATION datasets demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed method and achieve a tracking performance that outperforms other comparable methods.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows: In Section 2, we review the relevant literature. In Section 3, we discuss the specific implementation details of our method. Section 4 presents the experimental results. Finally, Section 5 provides the conclusions of this work.

Related work

Tracking by detection

Due to advances in target detection, the mainstream MOT methods1,5,13,16,17 have largely adopted the TBD paradigm in recent years.1 integrated appearance information to improve the tracking performance of being able to track objects over longer periods of time.16 emphasized the importance of the detector and utilized a CNN-based detector in conjunction with traditional tracking components like the Kalman filter to ensure reliable performance. The separation between detection and tracking in the aforementioned methods1,16 leads to a lack of global information utilization, thereby failing to effectively address the issues of false alarms and the re-identification of lost objects in dense and occluded scenarios. While certain studies have attempted to tighten the integration of detection and tracking13, the intrinsic independence of the detection model has not adequately addressed the problem of higher detection object counts resulting in increased time consumption. Li et.al18 introduced NanoTrack, a novel lightweight multi-object tracking method designed to enhance real-time performance by effectively integrating low-scoring detections. Although NanoTrack operates at higher speeds, its tracking accuracy remains limited. Compared to the existing TBD methods, our method learn the hidden shared structure between detection and embedding models, training the network in an end-to-end manner. This not only enhances tracking efficiency but also effectively extracts global discriminative semantic information to improve tracking performance.

One-stage MOT

The one-stage joint detection and tracking approach has gained widespread interest because of its streamlined and unified structure. A typical method19,20,21 is to develop a tracking-specific branch on top of an object detector to forecast either object tracking offsets or re-ID embeddings for associating data. As a notable advancement, JDE10 introduced the One-Stage tracking method, integrating the appearance embedding model within a single-shot detector. This tracking model simultaneously generates detection and corresponding embedding outputs. When compared to the TBD method, it lowers computational costs and is not constrained by the number of detected objects. However, despite its advantages, the JDE method utilizes the Darknet5314 as backbone network, which has limitations in feature extraction efficiency. Consequently, it is not optimally suited for scenarios requiring high real-time performance. Furthermore, JDE10 faces challenges to distinguish between similar objects and reidentify lost objects within crowded and occluded scenes. Sun et.al22 proposed an adaptive one-stage multi-object tracking algorithm based on sub-trajectories that incorporates a novel weight-updating module and appearance update strategy; however, its tracking accuracy and robustness remain limited. Unlike existing one-stage methods, we propose a lightweight multi-object tracking method. This method not only enhances tracking efficiency but also improves the identification of similar and lost objects through the use of a dual attention mechanism.

Attention mechanism in MOT

The attention mechanism has been widely employed in a range of research fields, including but not limited to image classification23,24, object detection14, semantic segmentation25,26, medical image processing27, spiking neural network28,29, domain adaptation30. Within the domain of Multi-Object Tracking,31 proposed the Double Matching Attention Network for data association, which utilizes spatial and temporal attention mechanisms to determine whether the detection and the tracklet belong to the same object.32 introduced the spatialtemporal attention mechanism for object state evaluation to solve the drift problem caused by object occlusion; The aforementioned methods primarily utilize attention mechanisms for data association and state estimation, neglecting the extraction of discriminative semantic features within the united detection and tracking framework. Furthermore, spatialtemporal attention is restricted to the candidate object, lacking awareness of global weight information. However, our method utilizes a dual attention mechanism to extract discriminative context features and capture instance-level semantic information shared among samples.

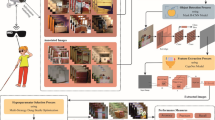

The overall of the proposed network is as follows: The backbone with lightweight model extracts fundamental visual features \(B1, B2, B3, B4\). Sample-perception features \(P2, P3, P4, E2, E3, E4\) are obtained through a dual attention mechanism (DAM), comprising intra-sample local attention mechanism (SLAM) and inter-sample global attention mechanism (SGAM). SLAM is utilized for extracting distinctive context information, while SGAM is adopted to capture shared instance-level semantics across samples. Finally, the tracking association component predicts and assigns object trajectories, ensuring accurate and reliable tracking.

Method

Overview and backbone

Our proposed lightweight multi-object tracking method, illustrated in Fig.2, comprises two primary components: the backbone network and the dual attention mechanism. The backbone network is responsible for extracting primary visual features. The dual attention mechanism consists of intra-sample local attention mechanism (SLAM) and inter-sample global attention mechanism (SGAM). The SLAM allows the model to focus on discriminative regions, enhancing the recognition of similar objects. Furthermore, the SGAM captures instance-level semantic information across samples and facilitates feature interaction between objects in different frames, thereby improving the re-identification performance for lost objects.

To enhance the real-time performance of multi-object tracking, a lightweight backbone network with minimal model parameters and FLOPs was employed. This backbone is designed to extract multi-scale visual features B2, B3, B4 based on the Feature Pyramid Network (FPN)33. During the top-down and bottom-up phases, a dual attention mechanism is utilized to obtain sample-perception features P2, P3, P4, E2, E3, E4 effectively capturing the interactive attention information both within and across samples.

Finally, each of the three task heads processes the fused feature maps at three scales to produce dense prediction maps for class, bounding box, and appearance embedding. These predictions are then combined with online association algorithms to generate object trajectories.

Dual attention mechanism

We propose the dual attention mechanism, which consists of two key components. Firstly, it adopts SLAM, enabling the model to focus on discriminative regions to retrieve instance context, thereby facilitating the effective distinguishing of similar objects. Secondly, it utilizes SGAM, which captures instance-level semantic information across samples. This promotes feature interaction between objects in different frames, thus enhancing the re-identification performance for lost objects.

Intra-sample local attention

SLAM is designed to capture detailed attention focused on the discriminative regions of an image, while minimizing interference from irrelevant information. It comprises two key components: a parallel channel module and an autocorrelation spatial module. The parallel channel module is responsible for extracting generalized features enriched with semantic information, whereas the autocorrelation spatial module suppresses background interference to extract discriminative features effectively. As illustrated in Fig.3, the parallel channel module processes the input features \(X=[\textrm{x}_1,\textrm{x}_2,...,\textrm{x}_c] \in \mathbb {R}^{H\times W\times C}\) by splitting them into two branches for pooling operations. Subsequently, the channel dimension is compressed using a \(1 \times 1\) convolution operation to produce a feature map with dimensions \(C/2 \times 1 \times 1\):

where, \(g_1\) denotes global average pooling and \(g_2\) denotes global max pooling. The function f refers to the \(1 \times 1\) convolution operation with shared weights across two branches, while \(\delta\) means the activation function. The features \(F_{up}\) and \(F_{down}\) are the outputs of two parallel branches.

Furthermore, the outputs of the two branches are concatenated to produce the feature map of dimensions \(C \times 1 \times 1\). Subsequently, by applying the \(\text {Sigmoid}\) function, we can obtain the parallel channel feature:

where, \(\sigma\) is the \(\text {Sigmoid}\) activation function.

The autocorrelation spatial module comprises three branches, with each branch individually performing a \(1 \times 1\) convolution operation on the input feature map, allowing us to obtain:

where, X denotes the input features, and \(\tilde{f}\) represents the \(1 \times 1\) convolution. The features \(\tilde{F_{up}}\), \(\tilde{F_{mid}}\), and \(\tilde{F_{lw}}\) correspond to the upper, middle, and lower branches after the convolution, respectively. After convolution, the channel dimension of the feature map is reduced to 1/8 of its original dimension.

SLAM comprises a parallel channel module and an autocorrelation spatial module. The parallel channel module is designed to extract rich semantic information, thereby enhancing the generalization performance of the features. Meanwhile, the autocorrelation spatial module is employed to suppress background interference, enabling the extraction of more discriminative features.

The upper and middle branches perform average pooling and max pooling operations, respectively, resulting in two feature maps of dimensions \(1 \times W \times H\). These are then concatenated to form a feature map of dimensions \(2 \times W \times H\). Subsequently, the channels are compressed by half using a \(7 \times 7\) convolution. Finally, the Sigmoid function is applied to the resulting feature of dimensions \(1 \times W \times H\) to obtain the spatial feature:

where, \(\tilde{g_1}\) denotes global average pooling and \(\tilde{g_2}\) denotes global max pooling, \(\hat{f}\) refers to the \(7 \times 7\) convolution.

Simultaneously, the convolution results from the upper and middle branches are multiplied and subjected to a softmax operation to produce a matrix of dimensions \((W \times H) \times (W \times H)\). The convolution result of the lower branch is then multiplied by this matrix, followed by a \(1 \times 1\) convolution to obtain the sample-wise feature, resulting in a feature map of dimensions \(C \times W \times H\):

where \(\tilde{\sigma }\) represents the \(\text {Softmax}\) activation function. Subsequently, the sample feature \(F_{sample}\) is summed with the input features \(X\). The resulting sum is then multiplied by the spatial feature \(F_{spatial}\) to generate the autocorrelation spatial weight:

Ultimately, the intra-sample local attention weight can be obtained:

Inter-sample global attention

We utilize the global correlation between samples to generate interaction-aware weights, capturing semantic information across samples and enabling the learning of representations with consistent re-identification performance.

As illustrated in Fig.4, we utilize the previously defined spatial feature \(F_{spatial} \in \mathbb {R}^{B \times 1 \times W \times H}\) and channel feature \(F_{channel} \in \mathbb {R}^{B \times C \times 1 \times 1}\) to compute the inter-sample global weight. Initially, a pooling operation compresses the spatial dimension to obtain \(F_{spatial}^{'} \in \mathbb {R}^{B \times 1 \times 1 \times 1}\). Concurrently, a mean operation reduces the dimension of \(F_{channel}\) along the channel, resulting in \(F_{channel}^{'} \in \mathbb {R}^{B \times 1 \times 1 \times 1}\). Therefore, the equation can be represented as:

By applying pooling and mean operations, the semantic information from the original spatial and channel dimensions is transformed into batch interaction information. We then perform a pixel-wise summation between \(F_{spatial}^{'}\) and \(F_{channel}^{'}\) to obtain the inter-sample interaction features \(F_{batch} \in \mathbb {R}^{B \times 1 \times 1 \times 1}\):

More specifically, \(F_{batch}\) can be represented as a vector comprising the interaction information \(F_{i}\) corresponding to each sample \(X_{i} \in \mathbb {R}^{C \times W \times H}\). This is defined as:

where, B indicates the total number of images in the current batch. Furthermore, we use the softmax function to generate the weight of the interaction information of each sample:

thus, the global attention weight vector across samples can be written as:

In the end, we perform a pixel-wise multiplication of the input feature X with the intra-sample attention \(W_{intra-sample}\) and the inter-sample attention \(W_{inter-sample}\) to obtain the output feature:

Online association

The Multi-Object Tracking (MOT) model is designed to detect and track multiple objects, outputting their respective bounding boxes and appearance embeddings. Each bounding box is defined by the parameters \((x, y, a, h)\), where \(x\) and \(y\) denote the coordinates of the center, \(a\) represents the aspect ratio, and \(h\) indicates the height. Furthermore, we establish the dynamic model for object tracking as follows:

where \(\nu _{x}, \nu _{y}, \nu _{a}, \nu _{h}\) represent the velocity components, and \(X^{k}=(x,y,a,h,\nu _{x},\nu _{y},\nu _{a},\nu _{h})\) denotes the object’s motion state. As illustrated in Fig. 5, the object motion state \(X^{k}_{t-1}\) at time \(t-1\) is used to estimate the object motion state \(X^{k}_{t}\) at time \(t\) by employing a Kalman filter in conjunction with the velocity vector \((\nu _{x}, \nu _{y}, \nu _{a}, \nu _{h})\).

In the process of conducting online tracking associations, we consider the Intersection over Union (\(IoU\)), the appearance embedding distance, and the Mahalanobis distance between the detected state (observations) and the estimated state (trajectories). We compute the cost matrix based on the appearance embeddings of the trajectories and observations, and then proceed with cost matching. When an observation is successfully matched with a trajectory, the appearance embedding of the trajectory is subsequently updated.

where \(f_t\) represents the appearance embedding of the trajectory at time \(t\), \(\hat{f}\) denotes the appearance embedding of the matched observation, and \(\eta\) is the smoothing coefficient for the appearance embedding. If a trajectory does not match any observation, it is considered lost. The trajectory will be removed from the trajectory pool after being lost for a predetermined period \(T\); however, if it is re-matched with an observation within this period, the trajectory will return to its normal tracking state. Conversely, if an observation does not match any existing trajectory, a new trajectory is initialized with that observation.

MOT Loss

The objective of the multi-object tracking network is to minimize the discrepancy between the predicted values and the ground truth. To achieve this, the Focal Loss is employed for the category branch’s task head. The loss function is defined as follows:

where \(\theta _{t}\) represents the weighting factor, \((1-p_t)^\phi\) denotes the modulating factor, and \(\phi\) stands for the adjustable focusing parameter. Since object tracking is typically treated as an instance-based classification problem, the appearance embedding employs the cross-entropy loss function:

where x denotes prediction and y denotes ground truth. In the detection branch, DIoU loss is used. If the Intersection over Union (IoU) between the anchor box and the ground-truth box exceeds or equals 0.5, the anchor box will be assigned. If the IoU falls within [0, 0.4), the anchor box is considered as background. If the IoU lies between [0.4, 0.5), the anchor box will not be included in the loss calculation. The anchor box with the highest IoU is designated as the ground truth box. DIoU loss is defined as follows:

where, b and \(b^{gt}\) denote the center points of the anchor and ground truth boxes, respectively, \(\rho (\cdot )\) represents the Euclidean distance, and c signifies the smallest diagonal length that encloses both bounding boxes. To address the issue of unbalanced loss in multi-task learning, we employ a task-independent uncertainty evaluation method. The objective function, which inherently balances the loss, is formulated as follows:

where \(\alpha , \beta , \gamma\) represent hyperparameters, i indicates different task heads, and \(\omega\) signifies the distinct branch loss weights for the category \((\omega _{f}^{i})\), the bounding box \((\omega _{d}^{i})\), or the appearance embedding \((\omega _{e}^{i})\). All of these parameters are learnable.

Experiment

Implementation details

We implemented the training of the proposed network using the PyTorch framework, with the final hyperparameters set as follows: the batch size was set to 8, and the model was trained with 200 epochs. Standard data augmentation techniques, including horizontal flipping, affine transformation, and color jittering, were employed. We utilized the SGD optimizer34 for training, with momentum and weight decay parameters set to 0.9 and 5e-4, respectively. The initial learning rate was 0.025, which was reduced by a factor of ten at the 100th and 150th epochs. The training process took roughly 80 hours on an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3090 GPU. We also employ a multi-scale dense connection structure (DCS) to enhance semantic feature extraction across various scales, and utilize a feature enhancement module (FEM) to balance detection bias within the unified network. Moreover, as shown in Table 1, we adopt a lightweight model to achieve more efficient tracking.

Datasets

We utilize the ETH55 and CityPerson56 datasets, which provide only bounding box annotations, to train the detection branch. Additionally, we employ the CalTech57, CUHK-SYSU58, MOT17 training sets59, and PRW60 datasets, which offer both bounding box and identity annotations, to train both the detection and embedding branches. The fully trained model is subsequently evaluated on the MOT1561, MOT1659, and MOT1759 test datasets.

Furthermore, we propose a multi-object tracking dataset, STATION, specifically designed for substation scenarios, to provide a more challenging benchmark. As shown in Fig. 6, the substation staff wear uniform with a similar appearance, making it difficult to distinguish effectively. The STATION dataset encompasses various real-world scenes, including occlusion and similar objects, which presenting challenges in re-identifying lost targets and distinguishing between similar objects. This dataset comprises 9 sequences with a total of 3142 frames.

Comparison with other methods

We compared our proposed method with several remarkable methods using the test sets of the MOT15, MOT16, and MOT17 benchmarks, with all evaluation results obtained directly from the official MOT Challenge server.

As shown in Table 2, our method outperforms all other methods on the MOT15 dataset in terms of IDF1, MT, and ML metrics. Although the lightweight design and the absence of an additional and time-consuming re-identification module result in our method having slightly lower MOTA and higher IDs compared to AP-HWDPL38, it is worth noting that our tracking speed is five times faster. Secondly, while our method is online and offline methods generally achieve higher MOTA as they leverage both past and future information for object tracking, our proposed method outperforms other offline methods such as NOMT35, CRF_Track36, and TSML_CDEnew37.

On the MOT16 dataset, our method outperforms other TBD and one-stage multi-object tracking methods, with our MOTA score exceeding that of the second-best method, HDTR43, by 3.3%. Furthermore, our method runs at a speed that is 11 times faster than HDTR43. This demonstrates the robust tracking performance of our method, its adaptability to high-resolution scenes in the MOT16 dataset, and its capability to meet real-time tracking requirements.

On the MOT17 dataset, we compared our method with the latest comparable multi-object tracking methods, MapTrack5 and TADN6. Our method surpasses these two approaches in five key metrics: MOTA, IDF1, MT, ML, and FPS. This comprehensive performance evaluation not only validates the effectiveness of our method but also highlights its superior speed and capability in real-time tracking scenarios.

We also performed a comparison of our method with representative one-stage MOT techniques, namely JDE10 and TADN6. Given that our primary optimization was aimed at addressing the time-consuming nature of JDE’s detection process, we implemented a lightweight backbone design to enhance the MOT system’s performance in real-time tracking scenarios. Our evaluation focused on comparing the performance of our method and JDE at a small resolution of 576x320. As illustrated in Table 3, our method substantially exceeded the performance of JDE and TADN on the MOT15, MOT16, and MOT17 datasets, with a significant increase in FPS of approximately 30% and four times. This demonstrates the superior tracking and speed performance of our method.

Furthermore, we conducted comparative experiments on the proposed STATION dataset. As illustrated in Table 4, our method outperformed JDE and TADN in all six metrics: MOTA, IDF1, MT, ML, IDs, and FPS. In particular, MOTA surpassed JDE by 10.5% and FPS was four times faster than TADN, attaining a speed of 61.8 frames per second. These experimental results demonstrate that our method effectively reidentifies lost objects and distinguishes between similar objects, particularly in scenarios involving occlusions and similar objects.

Ablation study

To evaluate the individual impact of each module in our algorithm, we devised five ablation comparison methods by deactivating one module at a time. Each comparison method is described as follows:

-

w/o FEM: We deactivated all the proposed modules, utilizing only the backbone network and task head to perform detection and tracking tasks.

-

w/o DCS: We deactivated the DCS multi-scale dense connection structure, maintaining only the FEM feature enhancement module which extracts appearance embedding features with strong semantics, aimed at balancing the bias of the unified network towards detection tasks and achieving joint optimization.

-

w/FEM & DCS: Utilizing only the FEM module and DCS structure, excluding the attention module; by integrating the DCS multi-scale dense connection structure, object detection is enhanced, especially for small targets.

-

w/SLAM: We adopted the SLAM into the FEM and DCS to extract intra-sample attention information, allowing the model to better focus on the discriminative areas of the image, reduce redundant information interference, and obtain rich features, thereby improving MOT performance.

-

w/SLAM & SGAM: Based on FEM, DCS, and SLAM, we adopted the SGAM to learn inter-sample correlations and generate interactive perception weights, to perceive semantic information across samples and extract consistent representations that mitigate the effects of crowding and occlusion.

We performed ablation studies on the MOTA and IDF1 metrics using both the validation and test sets of MOT-15, as well as the validation set of MOT16. As illustrated in Fig. 7, the introduction of the FEM and DCS modules resulted in noticeable improvements in both MOTA and IDF1 metrics. This indicates that the enhanced features and the use of multiple scales contribute positively to the performance of multi-object tracking (MOT). Furthermore, the utilization of DAM, including SLAM and SGAM, led to significant enhancements in both MOTA and IDF1. This improvement demonstrates that the DAM effectively extracts discriminative contextual features and captures instance-level semantic information shared among samples, thereby substantially enhancing the recognition performance for both similar and lost objects.

We conducted comprehensive experiments on the TUDCrossing, AVGTownCentre, PETS09-S2L2, and KITTI-19 datasets to validate our method’s robust tracking performance in static, crowded, and varied illumination scenarios. Additionally, these experiments demonstrated our method’s strong reidentification capabilities for lost objects.

Furthermore, we explored the impact of various hyperparameter settings on the network’s performance. As illustrated in Table 5, the learning rate coefficient (LR_Coeff) has three values, each corresponding to the contributions of the backbone, detection, and tracking to the learning rate, respectively. The results indicate that when the LR_Coeff values are set to [1, 1, 1], the MOTA and IDF1 metrics achieve their optimal values. Additionally, as shown in Table 6, we analyzed different configurations of loss weights, where \(\alpha\) represents the categorical branch, \(\beta\) represents the regression box branch, and \(\gamma\) represents the appearance embedding branch. The results demonstrate that MOTA and IDF1 achieved their best values when \(\alpha =0.5, \beta =0.5, \gamma =0.5\).

Adaptability to various scenes

In Fig. 8, the TUD-Crossing dataset61 (first row) depicts a scenario where numerous pedestrians cross an intersection in opposite directions.

In frame 43 (first column), targets with track IDs 8 and 10 are observed walking in tandem, and both are successfully tracked. In frame 73 (second column), the target with track ID 8 is occluded and disappears from view due to the target with track ID 12 moving in the opposite direction, resulting in only the target with track ID 10 being tracked. In frame 79 (third column), the target with track ID 8 is reidentified after being temporarily lost, and the target with track ID 10 continues to be tracked despite severe occlusion. This successful re-identification and tracking under challenging conditions can be attributed to our DAM. This mechanism employs SGAM, capturing instance-level semantic information across samples and facilitating feature interaction between objects in different frames, thereby enhancing the re-identification performance for lost objects. In the dataset KITTI-1961 (the second row), the image aspect ratio is quite extreme at 3.3:1, whereas our training data primarily features ratios ranging from 1:1 to 2:1. Moreover, significant illumination changes affect performance, presenting challenges for tracking. Nonetheless, experiments reveal that our method remains robust against variations in illumination and scale. Furthermore, the datasets AVG-TownCentre61 (the third row) and PETS09-S2L261 (the fourth row) illustrate that our method consistently maintains strong tracking performance in static, crowded, and varied illumination conditions.

Furthermore, To demonstrate the superiority of our method, we conducted comparative experiments using the MOT16 dataset and our proposed STATION dataset, alongside the JDE method. As illustrated in Fig. 9, within the STATION dataset (first row), the target with track ID 83 is partially visible due to occlusion in the first column and completely occluded in the second column. Given the uniform clothing and similar appearance of the substation staff, which presents a challenge for identifying lost targets, our method successfully reidentifies the target in the third column. In contrast, the JDE method (second row) exhibits an ID switch in the third column after the target is lost in the third column. This demonstrates that the introduction of the DAM in our method effectively extracts discriminative contextual features and captures instance-level semantic information shared among samples. Consequently, this mechanism significantly enhances the recognition performance for both similar and lost objects. Moreover, in the MOT16-06 sequence, the JDE method (fourth row) erroneously detects a billboard as a pedestrian with a track ID of 216, whereas our method avoids such false detections, underscoring its robustness and accuracy in challenging tracking scenarios.

Visualization

As illustrated in Fig. 10, the dual attention mechanism is visualized. Despite variations in illumination and scale, as well as the challenges posed by crowding and occlusion in these images, the adoption of SLAM and SGAM extracts distinct sample information and cross-sample semantic perception context. This mechanism pays more attention to discriminative region of the images while minimizing the impact of background and noise interference, thereby enhancing the model’s tracking capabilities.

Conclusion and future work

In this work, we propose an effective multi-object tracking method, which utilizes a dual attention mechanism to extract discriminative contextual features and capture instance-level semantic information shared among samples. This method significantly enhances recognition performance for both similar and lost objects. Additionally, we propose the STATION dataset, which encompasses various real-world scenes characterized by severe occlusion and similar objects. Extensive experiments conducted on the MOT and STATION datasets demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed method, achieving superior tracking performance compared to other comparable methods. In the Future, we will explore the use of graph neural networks to learn the instance-wise graph relationships, aiming to extract more distinctive features.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, [Lin Zuo, linzuo@uestc.edu.cn], upon reasonable request.

References

Wojke, N., Bewley, A. & Paulus, D. Simple online and realtime tracking with a deep association metric. In 2017 IEEE international conference on image processing (ICIP), 3645–3649 (IEEE, 2017).

Luo, C., Ma, C., Wang, C. & Wang, Y. Learning discriminative activated simplices for action recognition. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, vol. 31 (2017).

Yu, F. et al. Poi: Multiple object tracking with high performance detection and appearance feature. In Computer Vision–ECCV 2016 Workshops: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, October 8-10 and 15-16, 2016, Proceedings, Part II 14, 36–42 (Springer, 2016).

Abbaspour, M. & Masnadi-Shirazi, M. A. Online multi-object tracking with \(\delta\)-glmb filter based on occlusion and identity switch handling. Image and Vision Computing 127, 104553 (2022).

Wang, F., Zhang, R., Chen, C., Yang, M. & Bai, Y. Maptrack: Tracking in the map (2024). arXiv: 2402.12968.

Psalta, A., Tsironis, V. & Karantzalos, K. Transformer-based assignment decision network for multiple object tracking. Computer Vision and Image Understanding 103957 (2024).

Dai, P. et al. Learning a proposal classifier for multiple object tracking. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2443–2452 (2021).

Feichtenhofer, C., Pinz, A. & Zisserman, A. Detect to track and track to detect. In Proceedings of the IEEE international conference on computer vision, 3038–3046 (2017).

Kim, C., Fuxin, L., Alotaibi, M. & Rehg, J. M. Discriminative appearance modeling with multi-track pooling for real-time multi-object tracking. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 9553–9562 (2021).

Wang, Z., Zheng, L., Liu, Y., Li, Y. & Wang, S. Towards real-time multi-object tracking. In European conference on computer vision, 107–122 (Springer, 2020).

Sanchez-Matilla, R. & Cavallaro, A. Motion prediction for first-person vision multi-object tracking. In Computer Vision–ECCV 2020 Workshops: Glasgow, UK, August 23–28, 2020, Proceedings, Part IV 16, 485–499 (Springer, 2020).

Peng, J. et al. Tpm: Multiple object tracking with tracklet-plane matching. Pattern Recognition 107, 107480 (2020).

Bergmann, P., Meinhardt, T. & Leal-Taixe, L. Tracking without bells and whistles. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision, 941–951 (2019).

Redmon, J. & Farhadi, A. Yolov3: An incremental improvement. arXiv preprint arXiv:1804.02767 (2018).

Peng, J. et al. Chained-tracker: Chaining paired attentive regression results for end-to-end joint multiple-object detection and tracking. In Computer Vision–ECCV 2020: 16th European Conference, Glasgow, UK, August 23–28, 2020, Proceedings, Part IV 16, 145–161 (Springer, 2020).

Bewley, A., Ge, Z., Ott, L., Ramos, F. & Upcroft, B. Simple online and realtime tracking. In 2016 IEEE international conference on image processing (ICIP), 3464–3468 (IEEE, 2016).

Boragule, A., Jang, H., Ha, N. & Jeon, M. Pixel-guided association for multi-object tracking. Sensors. 22, 8922 (2022).

Li, W. et al. Nanotrack: An enhanced mot method by recycling low-score detections from light-weight object detector. In Proceedings of the 2024 2nd Asia Conference on Computer Vision, Image Processing and Pattern Recognition, 1–9 (2024).

Zhou, X., Koltun, V. & Krähenbühl, P. Tracking objects as points. In European conference on computer vision. 474–490 (Springer, 2020).

Lu, Z., Rathod, V., Votel, R. & Huang, J. Retinatrack: Online single stage joint detection and tracking. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition. 14668–14678 (2020).

Zhang, Z., Cheng, D., Zhu, X., Lin, S. & Dai, J. Integrated object detection and tracking with tracklet-conditioned detection. arXiv preprint arXiv:1811.11167 (2018).

Sun, L., Li, B., Gao, D. & Fan, B. Adaptive multi-object tracking algorithm based on split trajectory. The Journal of Supercomputing 80, 22287–22314 (2024).

Hu, J., Shen, L. & Sun, G. Squeeze-and-excitation networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 7132–7141 (2018).

Cheng, Q., Li, H., Wu, Q. & Ngan, K. N. Ba\(\hat{\,}\) 2m: A batch aware attention module for image classification. arXiv preprint arXiv:2103.15099 (2021).

Yuan, Y. et al. Ocnet: Object context network for scene parsing. arXiv preprint arXiv:1809.00916 (2018).

Zuo, L., He, P., Zhang, C. & Zhang, Z. A robust approach to reading recognition of pointer meters based on improved mask-rcnn. Neurocomputing. 388, 90–101 (2020).

Oktay, O. et al. Attention u-net: Learning where to look for the pancreas. arXiv preprint arXiv:1804.03999 (2018).

Zuo, L., Chen, Y., Zhang, L. & Chen, C. A spiking neural network with probability information transmission. Neurocomputing. 408, 1–12 (2020).

Zuo, L., Zhang, L., Zhang, Z.-H., Luo, X.-L. & Liu, Y. A spiking neural network-based approach to bearing fault diagnosis. Journal of Manufacturing Systems. 61, 714–724 (2021).

Zuo, L. et al. Challenging tough samples in unsupervised domain adaptation. Pattern Recognition 110, 107540 (2021).

Zhu, J. et al. Online multi-object tracking with dual matching attention networks. In Proceedings of the European conference on computer vision (ECCV). 366–382 (2018).

Chu, Q. et al. Online multi-object tracking using cnn-based single object tracker with spatial-temporal attention mechanism. In Proceedings of the IEEE international conference on computer vision, 4836–4845 (2017).

Lin, T.-Y. et al. Feature pyramid networks for object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2117–2125 (2017).

Zhang, S., Choromanska, A. E. & LeCun, Y. Deep learning with elastic averaging sgd. Advances in neural information processing systems 28 (2015).

Choi, W. Near-online multi-target tracking with aggregated local flow descriptor. In Proceedings of the IEEE international conference on computer vision, 3029–3037 (2015).

Xiang, J., Chao, M., Xu, G. & Hou, J. End-to-end learning deep crf models for multi-object tracking. arXiv preprint arXiv:1907.12176 (2019).

Wang, B., Wang, G., Chan, K. L. & Wang, L. Tracklet association by online target-specific metric learning and coherent dynamics estimation. IEEE transactions on pattern analysis and machine intelligence 39, 589–602 (2016).

Chen, L., Ai, H., Shang, C., Zhuang, Z. & Bai, B. Online multi-object tracking with convolutional neural networks. In 2017 IEEE international conference on image processing (ICIP), 645–649 (IEEE, 2017).

Sun, S., Akhtar, N., Song, H., Mian, A. & Shah, M. Deep affinity network for multiple object tracking. IEEE transactions on pattern analysis and machine intelligence. 43, 104–119 (2019).

Papakis, I., Sarkar, A. & Karpatne, A. Gcnnmatch: Graph convolutional neural networks for multi-object tracking via sinkhorn normalization. arXiv preprint arXiv:2010.00067 (2020).

Xu, Y. et al. How to train your deep multi-object tracker. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition. 6787–6796 (2020).

Zhang, L. et al. An anti-occlusion optimization algorithm for multiple pedestrian tracking. PLoS one. 19, e0291538 (2024).

Babaee, M., Athar, A. & Rigoll, G. Multiple people tracking using hierarchical deep tracklet re-identification. arXiv preprint arXiv:1811.04091 (2018).

Xu, J., Cao, Y., Zhang, Z. & Hu, H. Spatial-temporal relation networks for multi-object tracking. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision, 3988–3998 (2019).

Chen, L., Ai, H., Chen, R. & Zhuang, Z. Aggregate tracklet appearance features for multi-object tracking. IEEE Signal Processing Letters. 26, 1613–1617 (2019).

Ma, C. et al. Deep trajectory post-processing and position projection for single & multiple camera multiple object tracking. International Journal of Computer Vision. 129, 3255–3278 (2021).

Sukkar, M. et al. Enhancing pedestrian tracking in autonomous vehicles by using advanced deep learning techniques. Information. 15, 104 (2024).

Xu, L. & Wu, G. Multi-object tracking with grayscale spatial-temporal features. Applied Sciences. 14, 5900 (2024).

Henschel, R., Zou, Y. & Rosenhahn, B. Multiple people tracking using body and joint detections. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops, 0–0 (2019).

Yoon, Y.-c., Boragule, A., Song, Y.-m., Yoon, K. & Jeon, M. Online multi-object tracking with historical appearance matching and scene adaptive detection filtering. In 2018 15th IEEE International conference on advanced video and signal based surveillance (AVSS), 1–6 (IEEE, 2018).

Liu, Q., Liu, B., Wu, Y., Li, W. & Yu, N. Real-time online multi-object tracking in compressed domain. arXiv preprint arXiv:2204.02081 (2022).

Yoon, K., Gwak, J., Song, Y.-M., Yoon, Y.-C. & Jeon, M.-G. Oneshotda: Online multi-object tracker with one-shot-learning-based data association. IEEE Access. 8, 38060–38072 (2020).

Alikhanov, J., Obidov, D. & Kim, H. Lite: A paradigm shift in multi-object tracking with efficient reid feature integration. arXiv preprint arXiv:2409.04187 (2024).

Li, H. et al. Multi-object tracking via deep feature fusion and association analysis. Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence 124, 106527 (2023).

Ess, A., Leibe, B., Schindler, K. & Van Gool, L. A mobile vision system for robust multi-person tracking. In 2008 IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 1–8 (IEEE, 2008).

Zhang, S., Benenson, R. & Schiele, B. Citypersons: A diverse dataset for pedestrian detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 3213–3221 (2017).

Dollár, P., Wojek, C., Schiele, B. & Perona, P. Pedestrian detection: A benchmark. In 2009 IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 304–311 (IEEE, 2009).

Xiao, T., Li, S., Wang, B., Lin, L. & Wang, X. Joint detection and identification feature learning for person search. In Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 3415–3424 (2017).

Milan, A., Leal-Taixé, L., Reid, I., Roth, S. & Schindler, K. Mot16: A benchmark for multi-object tracking. arXiv preprint arXiv:1603.00831 (2016).

Zheng, L. et al. Person re-identification in the wild. In Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 1367–1376 (2017).

Leal-Taixé, L., Milan, A., Reid, I., Roth, S. & Schindler, K. Motchallenge 2015: Towards a benchmark for multi-target tracking. arXiv preprint arXiv:1504.01942 (2015).

Acknowledgements

This study is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (contract No. 62276054).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.Y.: Methodology, Writing-original-draft. W.L.: Writing-review. M.J.: Review, Editing. Y.D.: Visualization. H.P.: Visualization. L.Z.: Conceptualization, Review.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Informed Consent

We hereby confirm that informed consent has been obtained from all study participants and/or their legal guardians for the publication of any identifying information and/or images included in this manuscript. The participants have been informed that the information and images will be published in an online open-access publication, and they have provided explicit consent for this purpose.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, K., Luo, W., Jing, M. et al. Dual attention for multi object tracking with intra sample context and cross sample interaction. Sci Rep 15, 40665 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96506-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96506-5