Abstract

In this paper, a new metamaterial absorber (MMA) has been presented that shows dual-band absorption at 1.8 GHz and 3.5 GHz. The MMA cell has been designed on an FR4 substrate with the electrical dimension of 0.14λ0 × 0.14λ0 × 0.01λ0, calculating wavelength, λ0 at 1.8 GHz. Maximum absorption of 98.7% and 99.7% are attained by a unique design of a resonating patch consisting of two modified circular rings that are finalized through numerical Simulation in CST microwave studio. The MMA exhibits high angular stability up to 60° for incident angle as well as polarization angle variations. The analogous equivalent circuit is modeled in advanced design system (ADS) software, providing the same reflection, transmission, and absorption characteristics of 3D Simulation in CST. The absorption mechanism is investigated through current and electromagnetic field analysis. The MMA exhibits negative permittivity within 1 GHz—1.8 GHz and 2.08 GHz – 3.49 GHz and negative permeability with other frequency ranges. The prototype of a 3 × 6 array of the MMA cell is developed, and measurement is accomplished. The measured result exhibits well match with the simulated result. Moreover, The MMA displays good shielding effectiveness of 40.12 dB and 36.81 dB at 1.8 GHz and 3.5 GHz, respectively. The quality factors of the MMA are 30 and 22.3, with half power bandwidth of 60 MHz and 157 MHz. This new and unique MMA can be incorporated with various electronic devices for microwave shielding from GSM 1.8 GHz and sub-6, 5G 3.5 GHz signals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Metamaterial possesses some extraordinary electromagnetic and optical properties, which is why it can be used in many applications. Super lenses, high-performance antenna systems, electromagnetic cloaking, microwave sensing, and absorbers are some examples of metamaterial applications. Among these, metamaterial absorber (MMA) is a dominating field of research. Metamaterial absorbers are designed and used extensively in various frequency ranges depending on the applications in microwave, optical, or terahertz frequency spectra1. Perfect metamaterial absorber is highly expected in applications such reduction of radar cross-section reduction, cloaking, sensing, imaging applications, and shielding. After the first introduction by Landy et al.2, various metamaterial absorbers have been explored with variations in structural construction, bandwidth, angular stability, and polarization-independent properties.

Within current research work, an MMA structure with broadband absorption is presented by Tran et al. Here, absorption is increased with the help of coding concepts in a wide frequency spectrum3. Likely, Lan et al. developed an absorber that exposes broadband absorption from 1.91 GHz to 20.78 GHz, including multilayer resistive elements, providing over 90% absorption4. In another work, broadband MMA is constructed utilizing a metal-dielectric multilayer with a cone-shaped structure that provides more than 90% absorption within 3.93 GHz to 6.05 GHz and 11.64 GHz to 14.55 GHz. Polarized insensitivity property is achieved by the circular symmetry nature of the design5. Additionally, circular ring-based MMA is presented by Ali et al., which exhibits multiband absorptions with an absorption rate of above 98% from 8 to 12 GHz6. In Ref.7, tree-based fractal MMA is described by Chen et al. that exhibits wideband absorption extending from 4.9 GHz to 13.2 GHz. Here, wide-band absorption is accomplished through implanting lumped resistances. A microwave MMA sensor has been introduced in Ref8 that can be used for power imaging in the ISM band. It exhibits 84.2% conversion efficiency with 11.8 mV across the Schottky diode. In another work, authors presented MMA targeting near unity absorption at 5 GHz as well as 2.4 GHz9. The MMA can be used for Wi-Fi radiation shielding. Several MMAs are reported in Refs.10,11,12,13,14 that exhibit multiband resonances targeting various applications. Nipun et al. present an MMA that operates at 5 GHz and 13 GHz with high absorptions. This MMA finds its application of EMI shielding at 5 GHz along with the sensing capabilities at 13 GHz15. Among other works, Mahfazur et al. present MMA with 98.88% and 99.81% absorption levels at 2.4 GHz and 5 GHz, which is suitable for sensing cooking oil impurities and EMI shielding16. MMA application is offered in Ref.17, where MMA is incorporated with an antenna for reduction of radar cross-section along with backward radiation with gain enhancement by 2.7 dB. Similarly, mutual coupling is reduced using MMA in the MIMO antenna system, where MMA assists 37 dB mutual coupling reduction with better imaging resolution18. MMA having high refractive index sensitivity and enhanced quantity factor (Q factor) is offered by Lateef et al. Q factor of 84.5 is realized by exercising an asymmetrical structure that makes absorption polarization-dependent19. An asymmetric MMA structure is also reported in Ref.20, where MMA is effective for energy harvesting. Moreover, the authors describe an MMA absorber operating at terahertz frequency consisting of two squared patches displaying near unity absorption at 1.9 THz and 2.45 THz21. On the other hand, the absorber in THz is reported by Zhang et al., where the phase transition property of VO2 is exercised to provide above 90% absorption within 3.25 THz to 7.08 THz22. Likewise, Bilal et al. have demonstrated MMA exhibiting absorption above 90% within 400 nm to 2800 nm23, and MMA presented by Hossain et al. operates in the visible spectrum that may be applied for energy harvesting24. In Ref.25, a dual-band absorber that operates in the Ku band shows the resonances at 12.45 GHz and 14.18 GHz, with a peak absorption of 99.73% and 99.87%. In another work, dual-band absorption is achieved using cut wire pairs conjoined over the substrate material, and vertical sliding provides frequency adjustment flexibility26. This technique helps the frequency splitting of absorption spectra in the S-band.

From the above discussion, it is noticed that there is incessant demand for the design of a new metamaterial absorber for various applications. In particular, application frequency-targeted designs of MMA operating at GSM 1.8 GHz and 5G Sub 6 GHz frequency bands are less common in the literature. However, incorporating MMA, operating in these frequency bands with high shielding effectiveness, and isolating various communication devices and biomedical equipment from the mentioned microwave frequencies is important. Thus, the high performance and sensitivity of these devices will be ensured. Considering this fact, the present work focuses on the design of a dual-band metamaterial absorber that will operate at 1.8 GHz and 3.5 GHz. This targeted design intends to make MMA applicable to both GSM and 5G communication frequencies to shield other devices. The novelty of the presented work is that: (i) The structural design is new, containing modified ring resonators to increase absorption area and mutual coupling effect among the rings to adjust resonances at 1.8 GHz and 2.4 GHz with near-unity absorption; (ii) It provides 98.7% and 99.7% peak absorption at 1.8 GHz and 3.5 GHz; (iii) The analogous equivalent circuit is modelled and verified through ADS that shows a similar response of transmission, reflection, and absorption; (iv) The proposed structure shows stable absorption response for both TE and TM modes of signal with a high level of angular variation; (v) The MMA exhibits high shielding effectiveness of 40.12 dB and 36.81 dB at the targeted frequencies; (v) This proposed MMA can be applicable for microwave shielding against GSM 1.8 GHz and 5G 3.5 GHz frequency bands. The rest of the paper is organized as follows. In section two, the MMA design procedure is discussed. The absorption mechanism is studied in section three, where surface current, electric and magnetic fields, and power distribution over the structure are investigated. Section four discusses the design of an equivalent circuit, considering the scattering parameters and absorption pattern. Section five is dedicated to result analysis considering metamaterial properties and response of the structure for TE and TM modes of signals with the variation of the incident angles, Shielding effectiveness study, and probable applications. Measurement results are also included in this section, along with a comparison of the performance of the MMA with recent literature. Finally, a conclusion is drawn in section six that provides a concise description of the findings of the work.

MMA unit design and simulation

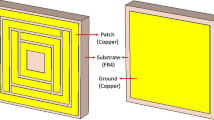

Metamaterial is a subwavelength structure whose resonance property can be controlled to absorb radiation at a specific frequency. By the appropriate design of a ring-based resonator, reflection and transmission can be prevented, and thus, the incident electromagnetic wave is absorbed, which causes energy conversion to a form of heat or another form of energy. Perfect absorption in MMA is attained by combining electric and magnetic resonances to change permittivity along with permeability, causing impedance that matches free space27,28. Appropriate impedance matching confirms the absorption of most energy instead of reflected by the metamaterials. Simultaneous resonances of electric and magnetic are required for perfect absorption29. In a metamaterial absorber, two conducting layers are conventionally printed over the opposite side of a substrate. One layer creates an obstacle to the transmitted signal, and another layer acts as the reflector. The incident signal is trapped between these two layers and undergoes destructive interference inside the substrate as multiple reflections occur that cause the absorption of the incident electromagnetic force27.

Design initiation and simulation

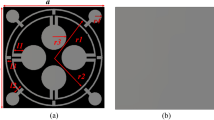

The unit cell of the proposed MMA is designed on an FR4 substrate having a dimension of 24 mm × 24 mm × 1.6 mm. The two opposite sides of this substrate are coated with two copper layers with a thickness of 0.035 mm. Within these two copper layers, one is articulated to create a resonator patch to provide near-zero reflection at the targeted frequencies of 1.8 GHz and 3.5 GHz. The other copper layer is used as a metal screen covering the total substrate area to obtain zero transmission. The thickness of this bottom copper is more than the skin depth of the imposed electromagnetic signals of targeted frequencies, ensuring zero transmission through the MMA. The complex quantities, permittivity \({\varepsilon (\omega )}={\varepsilon }_{1}+i{\varepsilon }_{2}\) and permeability µ(ω) = µ1 + iµ2 help to characterize the metamaterial as an effective medium, and the patch’s structural design controls these two quantities. So, the unit cell is optimized through numerical simulation so that MMA can provide values of \({\varepsilon }_{2}\) and µ2 such that MMA ensures signal loss inside it. The positive imaginary part helps to assist in signal loss in the material. Thus, it improves the absorptivity of the MMA. During the design of the MMA, focus is given to the near unity absorption through impedance matching at the targeted frequencies of 1.8 GHz and 3.5 GHz. \({\varepsilon (\omega )}\) is tried to keep nearly equal to µ(ω) at these targeted frequencies so that normalized impedance, Z \(\approx 1\) as \(Z=\sqrt{\frac{\mu }{\varepsilon }}\)30. The structural design is finalized through several numerical simulations, and the result is observed so that impedance matching is almost accomplished through the adjustment of the values of permittivity and permeability. The front and back view of the finalized MMA is presented in Fig. 1(a). Additionally, The layered structure view is displayed in Fig. 1(b). In the layered structure of Fig. 1(b), the top resonator patch is presented in gray color. Similarly, the colored bottom layer presents the copper backplane, which acts as a metal screen. Contrary to this, the middle layer marked with orange color represents the substrate. As expressed in Fig. 1(a), the resonating patch at the front side of the MMA contains two concentric copper rings with circular shapes. The outer ring helps to assist in obtaining peak absorption near 1.8 GHz, whereas the inner ring triggers the absorption at 3.5 GHz. To increase the absorption and get the peak absorption exactly at 1.8 GHz and 3.5 GHz, the shapes of the two rings are modified. These modifications increase the surface area of the patch as well as the mutual coupling effect between the rings to attain the targeted results. The finalized parameter values of the unit cell’s various segments are shown in Table 1.

In this design process, simulation is performed in CST microwave studio suite 2019. It is a 3D electromagnetic simulation tool that allows analysis of high-frequency multilayer structures like antennas, metamaterial, and other microwave components. The proposed cell is designed on this platform, and its performance is observed using a frequency domain solver. This solver utilizes finite element method (FEM) for solving electromagnetic field equations using numerical analysis31. CST divides the 3D model into elementary segments to generate meshes. The meshes are analyzed by solving. Maxwell’s equations describe electromagnetic fields’ interaction with the materials. CST estimates the fields surrounding the material by considering reflections, refractions, and resonances depending on selected excitation and the applied boundary conditions. The simulation arrangement is presented in Fig. 1(c). As expressed in Fig. 1(c), the unit cell of the proposed absorber is placed between two waveguide ports where the resonating patch is at the side of port 1, and the copper backplane is placed at port 2. The direction of the wave propagation is in the Z axis. In the simulation process, the boundary condition is applied, which considers electrical boundary conditions in the X-axis direction, whereas the magnetic boundary condition is considered in the Y direction for the normal incident wave. In the case of studying the effect of polarized signals, floquet ports are applied to provide flexibility in changing the incident wave angle and polarization angle. Unit cell boundaries are applied in X and Y directions in this port system. The wave originated from port 1 excites the structure, and electromagnetic resonance occurs at 1.8 GHz and 3.5 GHz, causing near-zero reflection. The transmitted signal goes through the substrate layer, and the back copper layer impedes the propagation. Due to its thickness being higher than the skin depth, the transmission becomes zero. So, the signal of the targeted frequencies is trapped inside the substrate; it undergoes multiple internal reflections and is eventually absorbed in the substrate layer. The absorption is calculated using the relation32, absorption, A = 1-S112-S212 , in which S112 and S212 indicate the reflected and transmitted energy portion, respectively. Since the transmission of EM waves through the proposed MMA will be zero, the absorption solely depends on the reflection coefficient, S11, which Eqn can determine. A = 1- S112.

Step-by-step design of the MMA cell

As stated earlier, the unit cell design undergoes numerous numerical simulation steps. The absorption spectra are observed at each step, and the design is finalized when the optimal outcome is attained. In the first stage, the design is initiated with a circular ring of 0.5 mm thickness at a radial distance of 11.3 mm from the center of the substrate (shown as design1 in Fig. 2). The corresponding absorption spectrum is presented in Fig. 3. As expressed in Fig. 3, it is realized that a peak absorption of 94.4% is attained at 2.04 GHz for design 1. In design2 of Fig. 2, another concentrating circular ring is added that bears a circular width of 1.63 mm. Figure 3 shows that the inclusion of this ring contributes to a new absorption peak at 4.04 GHz. In addition, due to the coupling effect, the resonance obtained at design 1 is noticed with a shift of peak absorption frequency. This shifting of peak absorption frequency is due to the capacitive effect between the two rings. However, this effect is not so prominent due to the large distance between these two rings (about 3.4 mm). In the next design step, four extended metallic stubs are added to the inner ring, as shown in Design 3 of Fig. 2. These extended stubs help to lower the peak absorption frequency at 3.54 GHz with 99.8% absorption. This modification also helps to restore the earlier peak absorption frequency at 2.05 GHz. Now, a modification in the outer ring is made, as shown in design4 of Fig. 2. This design step assists in establishing an absorption peak at 1.82 GHz, but due to the proximity between the extended stubs of the two rings, the maximum absorption decreases to 93%. This variation in the outer ring also provides a second peak absorption of 3.49 GHz with a magnitude of 99.6%. To nullify these negative effects and to set the peak absorption frequencies at exactly 1.8 GHz and 3.5 GHz with near-unity absorption, four additional metallic stubs are loaded at the four corners of the outer ring. The dimensions of these stubs are adjusted in the finalized design that provides maximum absorption of 98.7% at 1.8 GHz and 99.7% absorption at 3.5 GHz for the proposed structure, as illustrated in Fig. 2. The various information for different design steps are summarized in Table 2. The information in Table 2 shows that the proposed MMA exhibits narrow band absorption with half-power absorption bandwidth of 60 MHz and 157 MHz for absorption peaks at 1.8 GHz and 3.5 GHz, respectively. It is also noticed from Table 2 that the proposed MMA unit cell also shows a good quality factor of 30 and 22.3 at 1.8 GHz and 3.5 GHz, respectively, which is calculated using the relation of quality factor, Q = f/HPBW30. In this relation, f is the frequency of maximum absorption, whereas HPBW has a half-power absorption bandwidth. This excellent quality factor of this MMA indicates that this MMA can be utilized for detecting and sensing activities using GSM signals of 1.8 GHz and sub 6 GHz 5G frequency of 3.5 GHz.

Absorption mechanism

This section explores the absorption mechanism through current, electromagnetic field, and power loss density studies. The current on the top and bottom surfaces are shown in Fig. 4(a) at 1.8 GHz. It is noticed that the current at the resonating patch is mainly concentrated on the outer ring for this frequency. Clockwise current follows through the upper half of the outer ring, whereas antiparallel current is realized in the lower portion of the same ring. Moreover, this current is reasonably distributed on the outwardly extended metallic stubs, and it can be concluded that the outer metallic stub current contributes significantly to increasing the absorption at 1.8 GHz. A study of the backplane current (shown in Fig. 4(b)) for the same frequency reveals that the current density is low compared with the resonator current. The current intensity is comparatively high at the portion of the backplane that resides just below the high dense current of the top resonator.

Additionally, the top and bottom currents at these segments are antiparallel. Thus, this antiparallel current originates from the magnetic dipoles, which are the principal contributing factors to the absorption resonance at this frequency. Similarly, by observing Fig. 4(c), it is realized that the inner ring current mainly contributes to the resonance at 3.5 GHz. The horizontal portions of the inner ring bear a high concentration of currents, which is anti-parallel to the backplane current, as depicted in Fig. 4(c) and Fig. 4(d). These anti-parallel currents generate magnetic dipoles, and a strong magnetic resonance occurs that helps to originate near unity absorption at 3.5 GHz.

The electric field distributions at 1.8 GHz and 3.5 GHz are depicted in Fig. 5(a)-(b). As illustrated in Fig. 5(a), electric charges of opposite polarity are concentrated at the two opposite sides of the outer ring extended along the X-axis. This orientation of electric charges forms an electrical dipole on the patch that triggers the electric resonance at 1.8 GHz. The coupling of this electrical dipole with the metallic layer acts as an LC resonator33,34. Similarly, as shown in Fig. 5(b), the dipole formed in the second ring due to electric field distribution along the X direction contributes to the resonance at 3.5 GHz. The field distributions due to the magnetic effect are presented in Fig. 6(a)-(b). As depicted in Fig. 6(a), it is observed that magnetic field concentration is high in the Y direction. This field distribution forms magnetic polariton that causes an induction of magnetic resonance, resulting in the absorption of incident signal at 1.8 GHz34,35. Likely, the inner ring magnetic field oriented in the Y direction (shown in Fig. 6(b)) contributes to strong magnetic resonance for absorption at 3.5 GHz. Thus, the simultaneous occurrence of electric and magnetic resonances at the two targeted frequencies helps to absorb almost all electric as well as magnetic energy, and 98.7% and 99.7% absorptions are attained at 1.8 GHz and 3.5 GHz, respectively.

Further physical insight can be obtained by observing the power loss density pattern in the proposed MMA. Power loss density is illustrated in Fig. 7(a,b). As illustrated in Fig. 7(a), at 1.8 GHz, the power loss density is high at two vertical sides of the outer ring (marked as a and b). The area of the dome-shaped structure attached at four corners of the outer ring plays a vital role in increasing the absorption at 1.8 GHz. An increased area of these structures helps to improve the maximum absorption towards unity. On the other hand, inwardly extended concave shapes attached to the outer ring help to improve mutual coupling between inner and outer rings. Thus, electric field coupling between these two rings occurs with a high-power loss density. In the case of absorption at 3.5 GHz, the contribution of the inner ring is prominent, as expressed in Fig. 7(b). The marked area (c and d in Fig. 7(b)) shows high power loss density. This high loss density is due to the fact of strong coupling of the electric field between the two rings.

Equivalent circuit modelling

The equivalent circuit of the MMA can be designed based on the transmission line theory, in which each metallic strip can resemble the inductor. In contrast, capacitance is considered due to the separation between the two metallic conductors32. In the proposed MMA, two rings of the top resonator are separated with the copper backplane by the substrate material. Thus, an LC circuit is formed due to the copper backplane and outer ring. The inner ring and copper backplane also form a similar LC circuit. The mutual coupling between the two rings and electromagnetic couplings between the edges of the extended metallic stubs also exhibit inductive and capacitive effects. In addition to this, parasitic capacitances exist between ports and the MMA. As the substrate is the contributing material responsible for the signal’s absorption, this can be represented as the resistor of the electrical circuit, which consumes energy. Considering all these aspects, an equivalent circuit is designed and presented in Fig. 8. Here, Z0 represents the impedance of free space, whereas L1 and C1 are inductors and capacitors that are considered equivalent circuit components for the outer ring with the copper back. Similarly, L2 and C2 represent the resonating circuit elements for the inner ring with the backplane. The mutual coupling effects at the edges of the extended copper strips are presented by L3 and C3, whereas coplanar capacitance and inductance between the two rings are presented by L4 and C4, respectively. On the other hand, C5 is parasitic capacitance, and Zl is the equivalent resistance for substrates that are connected in parallel with other components of the circuit. Port 1 is connected with the equivalent circuit through Z0, whereas Port 2 is connected through impedance Z. Here, Z is the equivalent impedance with a very high value (theoretically infinite) representing zero transmission to the port 2. To identify the circuit components’ values and validate the circuit, it is modelled in the advanced design systems (ADS) software, and circuit values are tuned from the initial values of 1 pF and 1 nH for each capacitor and inductor, respectively. At every tuning step, the response of S11 and S21 are investigated to determine whether the obtained values provide the desired absorption at the targeted frequencies or not. Thus, the component values are optimized to attain and finalize the expected response. The scattering parameters so obtained from the finalized equivalent circuit are compared with the same obtained from the 3D structural Simulation in CST using the plots. As depicted in Fig. 9(a), it is determined that both S11 and S21 are well-matched. The high degree of matching in scattering parameters is achieved by carefully considering the circuit component’s values. It is noteworthy to mention that, in the proposed circuit model, S11 and S21 are completely independent of each other. It is revealed from the circuit that impedance Z is responsible for controlling the magnitude of S21. As the value of Z increases, S21 decreases to zero. At high values of Z, S21 becomes approximately Zero. Changing the values of Z does not show any impact on the resonances of S11. These findings reveal that Z represents the effect of the copper backplane that hinders the transmission of the signal through the MMA. In the proposed MMA, transmission is zero; thus, an infinite impedance is associated with it for the transmitted signal. So, an infinite resistance can be used at the terminal to off the signal transmission to port 2. The simulation result agrees with this analogy that a high value of resistance shows near zero transmission. On the other hand, the rest of the components of the circuit contribute to the adjustment of resonances of the S11 as well as the magnitude of it. Resistance Zl is especially equivalent to the absorption of the signal in the substrate, which acts as a pivoting factor in controlling the amplitude of the magnitude of the S11. Now, the absorption is determined from the extracted data of scattering parameters from the equivalent circuit, and the obtained result is plotted in comparison to the absorption data obtained from CST. A comparison of the absorption plots is depicted in Fig. 9(b), and it reveals the close similarity, confirming the validity of the equivalent circuit for the MMA.

Result analysis

This section analyzes results related to metamaterial characteristics, response of the MMA for polarized signals with incident and polarization angle variation, polarization conversion ratio, and Shielding effectiveness. Additionally, the measurement result is analyzed in comparison to the simulation result. Moreover, a comparative analysis has also been accomplished with other recent works.

Metamaterial characteristic analysis

The scattering behaviour of the proposed MMA is investigated by collecting data from CST. Electromagnetic resonance occurs when a wave imposes on the material, and this resonance can be represented by the Lorentzian equation presented in Ref.36. The scattering parameters that fit well with the Lorentz model have been derived through simulation in CST. Thus, the obtained transmission and reflection coefficients are presented in Fig. 10(a). The plot presented in Fig. 10(a) shows that transmission is zero over the observed frequency range.

On the other hand, at 1.8 GHz and 3.5 GHz, reflection approaches to zero. The near-zero reflections at these two frequencies provide 98.7% and 99.7% absorption, as indicated in Fig. 10(a). The metamaterial properties are investigated by extracting the permittivity and permeability; the plots are presented in Fig. 10(b) and (c). It is revealed that permittivity and permeability undertake positive–negative transition and vice versa at the frequencies of peak absorptions. It is also revealed that when permittivity is positive, permeability undergoes to negative, and the reverse occurs when permeability attains a positive value. Thus, the MMA exhibits a single negative behavior at any frequency. The MMA exhibits negative permittivity within 1 GHz—1.8 GHz and 2.08 GHz – 3.49 GHz and negative permeability at other frequency ranges. The normalized impedance, Z, has been examined for this MMA because impedance matching is essential to obtain unity absorption. The normalized impedance of the medium will be 1 + j 0 for unity absorption. In the plots presented in Fig. 10(d), the originated normalized impedance, Z is 0.8 + j 0.02 and 0.98 + j 0.09 at 1.8 GHz and 3.5 GHz, respectively, indicating a deviation from 1 + j 0. Due to impedance mismatching, a small portion of the incident wave is reflected at the target frequencies, and the obtained absorption deviates from the total absorption of 100%. The deviation of Z is high at 1.8 GHz, indicating comparatively high reflection compared to the response at 3.5 GHz and absorption at 98.7%. On the other hand, at 3.5 GHz, comparatively higher matching of the impedances causes the reflection to decrease with a near unity absorption of 99.7%.

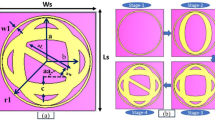

Absorption characteristic analysis for polarized wave

The study done so far is based on the normal incident wave. However, in practical application, an incident wave will not always be normal to the MMA. A perfect MMA will always respond similarly to all types of waves impinging at any angular position. The angular stability is further examined for transverse electric (TE) as well as transverse magnetic (TM) propagation modes. A floquet port is employed to generate TE and TM modes of signals that fall upon the resonating patch from the Z direction. The incident and polarization angles have been changed up to 60°. The absorption spectrum for different angles has been graphically presented in Fig. 11. Figure 11(a) shows the simulation response for TE mode. Almost identical absorptions are obtained as the incident angle θ changes from 0° to 60°. A similar result is also noticed for the simulation response of TM mode, as expressed in Fig. 11(b). It is also revealed from Fig. 11(a) and (b) that no frequency shifting occurs for the TE or TM mode of signals. Thus, a high degree of angular stability is noticed for the presented simulation response for incident angle variation of the proposed MMA. This high degree of stability in incident angle variation is attained due to the circular symmetric structure of the proposed MMA. It is observed that the lack of circular symmetric structure caused a variation in the response for different incident angles. If the substrate is rotated 90° clockwise or anticlockwise, the structure looks the same. The side exposed under a magnetic or electric field remains the same. Due to this symmetry, no change in absorption is noticed for angle changes for both TE and TM modes, making the proposed structure suitable for real-world application. In real scenarios, the incident electromagnetic wave will always not be perpendicular to the resonator. Thus, maintaining symmetry in structural design helps to obtain stable performance. However, slight deviations in peak absorptions and resonance frequency shifts are observed from the experimentally measured responses of incident angle variations for TE or TM mode, as expressed in Fig. 11(c) - (d). As revealed in Fig. 11(c), for the TE signal, when θ = 0⁰, 99.99% and 99.89% peak absorptions are found at 1.8 and 3.5 GHz, respectively. For the angular variation of 20⁰, the maximum absorption frequency shifting occurs with 96.99% at 1.794 GHz and 96.9% at 3.482 GHz. At θ = 40⁰, the 99.6% absorption at 1.806 GHz and 99.49% at 3.502 GHz are noted. Finally, at θ = 60⁰, absorption levels of 98% at 1.803 GHz and 97.9% at 3.499 GHz are perceived. The measured responses for incident angle variations of TM modes are presented in Fig. 11(d). At θ = 0⁰, the peak absorption of 99.99% and 99.89% are obtained at 1.8 GHz and 3.5 GHz, respectively. At 20⁰, the maximum absorption of 98.9% and 98.9% are obtained at 1.799 GHz and 3.49 GHz, respectively. At θ = 40⁰, the peak absorption of 99.19% at 1.802 GHz and 99.19% at 3.497 GHz, and θ = 60⁰ the absorption of 96.58% at 1.804 GHz and 97.39% at 3.501 GHz are detected. These insignificant deviations in TE or TM mode result in experiment measurement of incident angle variation due to the prototype’s imperfect fabrication and placement during measurement.

The simulation analysis of the influences of polarization angle, \(\Phi\) on absorption phenomena in both TE and TM modes are presented in Fig. 11(e) and (f), respectively. In TE mode, as the angle, \(\Phi\) changed from 0⁰ to 60⁰, slight variations in absorption as well as in frequency have been observed. The highest peak absorption is attained at \(\Phi\) = 0⁰. At \(\Phi\) = 20⁰, the resonances occurred at 1.803 GHz and 3.511 GHz with a peak absorption of 97.45% and 98.96%, respectively. For \(\Phi\) = 40⁰, the resonances occur at 1.804 GHz and 3.52 GHz with a peak absorption of 96.86% and 98.4%, and for \(\Phi\) = 60⁰, the resonances occur at 1.804 GHz and 3.518 GHz with 96.45% and 97.75% absorption, respectively. As shown in Fig. 11(f) angular deviation in polarization in TM mode causes only a small deviation in peak absorption at \(\Phi\) = 20⁰. At this angle, 98.38% and 99.99% absorption resonances occur at 1.803 GHz and 3.515 GHz, respectively. Now, the effect of cross-polarization is also studied by extracting cross-polarization data. In the case of some metasurface absorbers, signal conversion takes place due to their anisotropic pattern. Anisotropic structure causes the conversion of the incident wave from co-polarization to cross-polarization rather than being absorbed37. Using Eq. (1) the obtained absorption is further computed, taking into account all of the effects of co and cross-polarized data9:

In Eq. (1), \({r}_{xx}\) and \(t_{xx}\) represent the reflection and transmission coefficient of co-polarization, whereas \(r_{xy}\) and \(t_{yx}\) define the reflection and transmission coefficient of cross-polarization. The absorption equation can be simplified as follows because the transmitted signal components are zero due to the copper at the backside9:

The obtained absorption based on the co and cross-polarized reflection coefficient is depicted in Fig. 12. As the cross-polarization reflection coefficient is almost zero, the absorption spectra is identical to that of a typical incident wave. Total absorption eventually falls if a greater percentage of the wave is transformed into the cross-polarization component, and the meta-structure will function as a polarization converter rather than an absorber38. Thus, the proposed metastructure acts as a perfect absorber that provides similar absorption characteristics for all types of incident waves irrespective of angular variation. Moreover, it is also free from signal conversion.

Effect of different substrate materials

To understand the effect of the different substrate material, a simulated study is made using Rogers (RT 5880), paper, polycarbonate, Mica, glass along with the FR4 of the proposed MMA. The dielectric constant of these materials are 2.2, 2.3, 2.9, 6, 4.8, and 4.3. The absorption spectrum for these substrate materials is shown in Fig. 13. As depicted in Fig. 13. It is noticed that maximum absorption is obtained for the FR4 substrate (dielectric constant of 4.3), and it occurs at the targeted frequency. However, as the deviation of the dielectric constant increases, the absorption level decreases. Rogers, paper, and mica do not contribute to the absorption, whereas glass shows near-unity absorption with a frequency deviation from the targeted frequency. This result indicates that the proposed resonator and the FR4 substrate material provide better impedance matching with the free space impedance. Moreover, FR4 is a very durable flame-redundant material. It exhibits high stability and mechanical strength. It also shows moisture and chemical resistance properties. In addition to this, FR4 is cost-effective and provides lower frequency resonances in compact dimensions compared to Rogers. Considering all these facts in the present work, FR4 is the suitable substrate material.

High-frequency absorption study

Although the targeted operating frequency of the presented work is within 5 GHz, the numerical simulation is performed by extending the frequency range up to 20 GHz. The resultant absorption spectra is illustrated in Fig. 14. It is noticed that two sets of additional absorption peaks are obtained between 8 to 12 GHz, and another set is within 12 GHz to 18 GHz. A similar, multiple absorption band is also noticed in Ref.39, where a bianisotropic metasurface is engaged that shows electromagnetic coupling for exhibiting multi-band absorption with partial reflection extended from C band to the Ku band. In the presented MMA, absorption peaks are almost 70% in the X band, with peak resonance frequencies of 8.96 GHz and 11.47 GHz, respectively. On the other hand, in the Ku band, five distinct absorption peaks are attained with maximum absorption levels of 89.1%, 86.3%, 99.95%, 97.1%, and 90.8% at 14.66 GHz, 16.61 GHz, 16.39 GHz, 17.01 GHz, 18.04 GHz, respectively. Moreover, in the Ku band, the average absorption level is almost 63%, and off-resonance absorption is more than 36%, indicating comparatively higher absorption within a broader range of frequencies than lower frequencies. In the presented work, FR4 is used as a substrate that is a lossy substrate material with a high degree of loss tangent value. Its dielectric loss increases with an increase in frequency that is more dominant, above 10 GHz. Due to this reason, FR4 is not preferable for the high-frequency applications, and the work is confined within lower frequency band. It is noticed that high dielectric constant FR4 provides lower frequency resonances within a small dimension compared with some other materials such as Rogers.

Measurement result analysis

Two different methods can be employed for measuring: (i) one is a far-field measurement technique, and (ii) another is a waveguide port. In the far-field method, two horn antennas are placed side by side. One acts as the source of the electromagnetic wave and the other is used to receive the reflected wave. The material under test (MUT) will be placed at a far field distance from the antenna. In this measurement system, the dimension of MUT will be large enough to be larger than the antenna footprint to get a more accurate result. In this technique, the measurement is taken in an anechoic chamber surrounded by the absorber so that unwanted reflected signals can be omitted. However, the conventional far-field measurement technique is not employed in this study due to the constraints of laboratory facilities. Instead, two different waveguide ports are utilized: (i) one having the dimension 130 mm × 66 mm for obtaining the result around 1.8 GHz, (ii) another with the dimension of 86 mm × 44 mm for the data extraction around 3.5 GHz. The 3 × 6 array of MMA unit cell prototype is developed with a 72 mm × 144 mm dimension. The array’s dimension is more significant than the two above waveguide ports. It ensures that all the incident waves are exposed on the resonator surface and reflected back from it, confirming better accuracy in the measurement result. The developed prototype is depicted in Fig. 15(a), whereas the measurement arrangement is shown in Fig. 15(b). In the experimental setup, the waveguide adapter is connected to one end of the coaxial cable through an impedance-matched connector. The other end of the coaxial cable is attached to a vector network analyser (VNA) port. The VNA has two ports that can be used to transmit and receive electromagnetic waves. In our experimental setup, one port is employed to transmit the incident wave and to receive the reflected signal. The second port is not used to receive the transmitted signal because the metal screen at the back makes the transmission zero. The MMA under test is placed in front of the waveguide adapter in such a way that the transmitted signal falls upon the MUT’s resonator side.

The reflection coefficient is first identified for a copper sheet of the same size as MUT during the measurement process. Then, the reflection coefficient is measured for the MMA under test. The difference between these two reflection coefficients provides the actual reflection coefficient for the MUT, eliminating the reflection for surroundings. Since MMA contains a full copper backplane, the measured transmission coefficient will eventually be zero. This measured S11 is utilized to explore the absorption. Thus, measured absorption is plotted along with simulated absorption, and the graphs are presented in Fig. 16. It is noticed that the measured absorption peak matches maximum absorption at 1.8 GHz as well as 3.5 GHz with slightly higher absorption peaks of 99.99% and 99.89% compared to the simulation.

Additionally, in the measured result, at 1.8 GHz, more than 90% absorption is achieved between 1.7915 GHz and 1.8095 GHz, which is wider than the simulated bandwidth. On the other hand, around 3.5 GHz (between 3.47 to 3.5195 GHz), more than 90% absorption is attained, which closely matches the simulation response. Thus, the measured result shows a good similarity with the simulated results. The reason for the small deviation between the simulation and measurement results is the slight incongruities that have occurred due to the unevenness of the substrate used for the fabrication, fabrication error, and coupling effect for waveguide ports. Moreover, the placement of the array between the waveguide ports is another factor in obtaining an accurate measurement result. It is noticed that to get a more accurate result, the array dimension needs to be higher than the waveguide port dimension. Otherwise, a portion of the incident wave will not be imposed upon the MMA; hence, the measured result may deviate from the simulation. The measurement accuracy level can be improved if these limiting factors are addressed.

Shielding effectiveness and EMI shielding from GSM and 5G systems

The proliferation of technologies has led to the successive improvement of electronic appliances, resulting in the rise of electromagnetic (EM) radiation interference. These factors have been found to harm both gadgets and human health40. Due to this, researchers have focused extensively on EM shielding phenomena to create efficient EMI shielding devices and reduce EM contamination41. Electronic devices such as cell phones operating based on GSM technologies functioning at 1.8 GHz and Wi-Fi, and WiMAX based on 3.5 GHz (5G communication) can produce unwanted interference on the microwave devices used for various applications such as sensors, sensing instruments, televisions, medical devices which can be affected by the undesirable EMI42. Providing EMI shielding against 1.8 GHz and 3.5 GHz can achieve the shielding against the specific devices operating at those frequencies. For this reason, the design of the MMA is manipulated to control resonances at 1.8 GHz and 3.5 GHz. The strength of the EMI shielding delivered by the MMA is quantified through the shielding effectiveness (SE) parameter. In the dB scale, the total SE is the summation of the influence of transmission and reflection. SE of the suggested MMA is determined by the following equation43,44.

The incident and transmission components of the E-field are denoted as EI and ET, respectively. For the SE (dB) value more significant than -10 dB, the multiple reflection term of SE can be disregarded45. Moreover, the absorber’s copper backplane blocks the EM waves’ propagation. Due to transmission, the SE is significantly large and remains constant all over the frequency range. However, the overall SE of the absorber is mainly influenced by the reflective component of the absorber. From the measurement data, the SE (dB) of the absorber is calculated and equated with simulated responses as depicted in Fig. 17. At 1.8 GHz, the measurement response of SE (dB) is obtained at 40.12 dB, which is 7.31 dB higher than the simulation response. In contrast, at 3.5 GHz, the value is 36.81 dB, which is 0.22 dB less than the simulation response. Since both the simulation as well as measured SE at the targeted resonance frequencies are well ahead of the commercial value of 20 dB46, the proposed MMA can be a piece of good equipment for commercial EMI shielding against the GSM and 5G communication systems.

It is realized that the MMA exhibits good shielding effectiveness, indicating the capability to absorb undesirable electromagnetic waves. The selective shielding of the electromagnetic signal is necessary to isolate 5G and GSM band signals from other signals, such as ISM band signals and Wi-Fi signals (2.4 GHz, 5 GHz), to reduce interference. The proposed MMA can be incorporated with the enclosures of various electronic devices that can shield inner modules from being interfered with by GSM and 5G communication signals. This shielding mechanism may be more effective in biomedical imaging systems that use ISM band signals and are prone to interference with GSM or 5G communication signals. The proposed MMA can help shield these unwanted signals from biomedical imaging and thus increase the sensitivity of the biomedical imaging equipment. In the case of low-frequency bands such as GSM 900 MHz and 1800 MHz, a special shielding mechanism is required to isolate the communication devices in dense infrastructure development, particularly in metropolitan environments. Moreover, in the 5G communication systems, multiple wireless components are closely packed; in that case, interference between the system components becomes inevitable. So, exploring the compact shielding materials that can shield microwave frequency signals is necessary. In the present study, the MMA is compact and is identified with an EMR value of 6.94, and it provides good SE values of 40.12 dB and 36.81 dB at 1.8 GHz and 3.5 GHz, respectively. Thus, this small-sized MMA can be a good candidate for isolating Wi-Fi and ISM band devices to avoid unwanted interference imposed by GSM 1800 MHz and 5G, sub 6 G communication devices operating at 3.5 GHz. Moreover, it provides better isolation among 5G communication components to reduce the coupling effect in the MIMO antenna system.

Comparative analysis

In recent work, an asymmetric resonator-based MMA has been reported in Ref47. to reduce the radiation in 5G frequency. Moreover, Bakir et al. demonstrate that MMA is applicable for energy harvesting in frequencies 900 MHz, 1.37 GHz, 1.61 GHz, 1.80 GHz, and 2.55 GHz, respectively. However, a lack of symmetry impedes its performance in the case of polarized signals48. The performance of the MMA is equated with other recent works and expressed in comparison Table 3. This comparison is made based on physical dimension, peak absorption frequencies, percentage peak absorption, compactness, and applications. The compactness is identified through effective medium ratio (EMR), which is considered to be at minimum peak absorption frequency using the mathematical Eqn. EMR = λ/L, where λ is the wavelength, L is the maximum length for MMA cell. This Table shows that the dimension for MMA cell of Ref.49 is high compared to the proposed MMA. Moreover, this MMA shows polarization-insensitive characteristics, and its operating frequency is comparatively higher than this proposed MMA. On the other hand, the physical dimension of the MMAs in Refs.50,51,52,53,54,55 are less compared to the proposed MMA. However, close observation reveals that the minimum peak absorption frequencies of these MMAs are higher compared to the proposed one and are not designed to target application-oriented frequencies. MMA of Ref.54 shows high EMR values, indicating that the design is more compact compared to, but in this work, absorption levels for the intended frequencies are low. Thus, the presented MMA in this article exhibits comparatively better performance. Moreover, the design is unique, focusing on absorption from the frequencies of the GSM 1.8 GHz band and 5G, 3.5 GHz band. The proposed structure also exhibits polarization as well as incident angle insensitivity with near-unity absorption that is achieved through a rotating symmetry structure with dimension compactness.

Conclusion

An MMA is presented in this paper that shows 98.7% along with 99.7% absorptions at 1.8 GHz and 3.5 GHz, targeting microwave absorption from GSM and 5G sub-6 GHz band. An FR4 substrate is taken to initiate this design. The high absorptions at desired frequencies are achieved through unique design considerations in a resonating patch that consists of two modified circular rings. The surface current and electromagnetic field are analyzed to study the MMA’s interaction with the incident electromagnetic waves. Similar responses for S11, S21, and absorption are obtained by modelling and verifying the corresponding equivalent circuit using ADS. The proposed MMA exhibits single negative features with alternative positive to negative transitions of permittivity and permeability. The performances for TE and TM modes of electromagnetic waves are examined to provide similar absorption characteristics for the variation of the incident as well as polarization angle up to 60°. The absorption is also numerically calculated considering cross-polarized signals, and the obtained result shows that the absorption is similar, indicating that it is unaffected by the cross-polarized effect. In addition to this, the prototype is developed, and measurements are taken. A good agreement between the measured and simulation results is also attained. The proposed MMA shows a high SE of 46.12 and 36.81 dB at 1.8 GHz and 3.5 GHz. Due to its stable performance, high absorption, and SE, this new MMA acts as a perfect absorber that can be applicable for microwave shielding from GSM and 5G sub-6 GHz frequency bands.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Abdulkarim, Y. I. et al. A review on metamaterial absorbers: Microwave to optical. Front. Phys. 10, 893791 (2022).

Landy, N. I., Sajuyigbe, S., Mock, J. J., Smith, D. R. & Padilla, W. J. Perfect metamaterial absorber. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100(20), 207402 (2008).

Tran, M. C. et al. Broadband microwave coding metamaterial absorbers. Sci. Rep. 10(1), 1810 (2020).

Lan, H. W. et al. Low-frequency broadband multilayer microwave metamaterial absorber based on resistive frequency selective surfaces. Appl. Opt. 62(4), 1096–1102 (2023).

Kim, Y. J. et al. Dual broadband metamaterial absorber. Opt. Express 23(4), 3861–3868 (2015).

Ali, H. O., Al-Hindawi, A. M., Abdulkarim, Y. I. & Karaaslan, M. New compact six-band metamaterial absorber based on Closed Circular Ring Resonator (CCRR) for Radar applications. Optics Commun. 503, 127457 (2022).

Chen, T., Li, S.-J., Cao, X.-Y., Gao, J. & Guo, Z.-X. Ultra-wideband and polarization-insensitive fractal perfect metamaterial absorber based on a three-dimensional fractal tree microstructure with multi-modes. Appl. Phys. A 125, 1–8 (2019).

Alkurt, F. Ö. et al. Microwave power imaging detector based on metamaterial absorber. Opt. Eng. 59(8), 087104–087104 (2020).

Moniruzzaman, M. et al. Tuning metallic stub loaded symmetrical resonator based dual band metamaterial absorber for wave shielding from Wi-Fi frequencies. Alex. Eng. J. 63, 399–414 (2023).

Baqir, M. A. et al. Fractal metamaterial based multiband absorber operating in 5G regime. Optik 266, 169626 (2022).

Zhang, F. et al. A multi-band binary radar absorbing metamaterial based on a 3D low-permittivity all-dielectric structure. J. Alloy. Compd. 814, 152300 (2020).

Dewangan, L. & Mishra, N. K. Multiband polarization insensitive metamaterial absorber for radar cross-section reduction. AEU-Inter. J. Electron. Commun. 168, 154706 (2023).

Hossain, M. B., Faruque, M. R. I. & Islam, M. T. Double elliptical resonator based quadruple band metamaterial absorber for EMI shielding applications in microwave regime. Alex. Eng. J. 69, 193–206 (2023).

Saad, A. A. R. Miniaturized multi-band polarization-insensitive microwave absorber using microstrip interdigital capacitor. AEU-Inter. J. Electron. Commun. 137, 153830 (2021).

Nipun, M. M. K. et al. Interconnected Circular Ring Resonator based Single Negative Perfect Metamaterial Absorber for Wireless Communication Systems. Opt. Quant. Electron. 56(6), 1–20 (2024).

Rahman, A. A. M. et al. Circular-ring tied arc loaded excellent metamaterial absorber for EMI shielding of Wi-Fi signal and impurity sensing of cooking oil. Eng. Sci. Technol. Inter. J. 58, 101838 (2024).

Jeong, H., Kim, Y., Tentzeris, M. M. & Lim, S. Gain-enhanced metamaterial absorber-loaded monopole antenna for reduced radar cross-section and back radiation. Materials 13(5), 1247 (2020).

Ahmed, A., Kumari, V. & Sheoran, G. Reduction of mutual coupling in antenna array using metamaterial surface absorber. AEU-Inter. J. Electron. Commun. 160, 154519 (2023).

Lateef, O. S., Al-Badri, M., Al-Badri, K. S. L. & Mohammed, S. A. Polarization-insensitive Archimedes’-spiral-shaped ultrathin metamaterial absorbers for microwave sensing application. Sci. Rep. 13(1), 19445 (2023).

Hasan, M. S. et al. Double elliptical resonator based quad-band incident angle and polarization angle insensitive metamaterial absorber for wireless applications. Opt. Laser Technol. 171, 110334 (2024).

Wang, B.-X., He, Y., Lou, P. & Xing, W. Design of a dual-band terahertz metamaterial absorber using two identical square patches for sensing application. Nanoscale Adv. 2(2), 763–769 (2020).

Zhang, M. & Song, Z. Switchable terahertz metamaterial absorber with broadband absorption and multiband absorption. Opt. Express 29(14), 21551–21561 (2021).

Bilal, R. M. H. et al. Nickel-based high-bandwidth nanostructured metamaterial absorber for visible and infrared spectrum. Nanomaterials 12(19), 3356 (2022).

Hossain, I. et al. Polarization-independent broadband optical regime metamaterial absorber for solar harvesting: A numerical approach. Chin. J. Phys. 71, 699–715 (2021).

Al-badri, K. S. L., Abdulkarim, Y. I., Alkurt, F. Ö. & Karaaslan, M. Simulated and experimental verification of the microwave dual-band metamaterial perfect absorber based on square patch with a 450 diagonal slot structure. J. Electromagn. Waves Appl. 35(11), 1541–1552 (2021).

K. S. L. Al-Badri, N. Karacan, E. M. Kucukoner, and E. Ekmekci, Sliding planar conjoined cut-wire-pairs: A novel approach for splitting and controlling the absorption spectra, Journal of Applied Physics, 124, no. 10, (2018).

Prasada, N. K., Naikb, B. R., Babuc, T. A., Rajasekhard, S. & Madhavie, N. Theory, design and characterization of metamaterial absorbers: a formal assessment. J. Optoelectron. Biomed. Mater. 15(1), 31–41 (2023).

Tao, H. et al. A metamaterial absorber for the terahertz regime: design, fabrication and characterization. Opt. Express 16(10), 7181–7188 (2008).

W. Zhu, Electromagnetic Metamaterial Absorbers: From, Metamaterials and Metasurfaces,. 133, (2019).

Moniruzzaman, M., Islam, M. T., Muhammad, G., Singh, M. S. J. & Samsuzzaman, M. Quad band metamaterial absorber based on asymmetric circular split ring resonator for multiband microwave applications. Results Phys. 19, 103467 (2020).

Moniruzzaman, M. et al. Symmetric resonator based tunable epsilon negative near zero index metamaterial with high effective medium ratio for multiband wireless applications. Sci. Rep. 11(1), 21842 (2021).

Rabbani, M. G. et al. Dumbbell shaped structure loaded modified circular ring resonator based perfect metamaterial absorber for S, X and Ku band microwave sensing applications. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 5588 (2024).

D. Schurig, J. Mock, and D. Smith, Electric-field-coupled resonators for negative permittivity metamaterials, Applied physics letters, vol. 88, no. 4, (2006).

Luo, H., Cheng, Y. & Gong, R. Numerical study of metamaterial absorber and extending absorbance bandwidth based on multi-square patches. Eur. Phys. J. B 81, 387–392 (2011).

Ye, Y. Q., Jin, Y. & He, S. Omnidirectional, polarization-insensitive and broadband thin absorber in the terahertz regime. JOSA B 27(3), 498–504 (2010).

Moniruzzaman, M. et al. Inductively tuned modified split ring resonator based quad band epsilon negative (ENG) with near zero index (NZI) metamaterial for multiband antenna performance enhancement. Sci. Rep. 11(1), 11950 (2021).

Ahmed, F., Hassan, T. & Shoaib, N. Comments on an ultrawideband ultrathin metamaterial absorber based on circular split rings. IEEE Antennas Wirel. Propag. Lett. 19(3), 512–514 (2020).

Kundu, D., Mohan, A. & Chakrabarty, A. Comment on Wide-angle broadband microwave metamaterial absorber with octave bandwidth. IET Microwaves Antennas Propag. 11(3), 442–443 (2017).

Ahmed, F., Hassan, T. & Shoaib, N. A multiband bianisotropic FSS with polarization-insensitive and angularly stable properties. IEEE Antennas Wirel. Propag. Lett. 19(10), 1833–1837 (2020).

J.-M. Thomassin, C. Jérôme, T. Pardoen, C. Bailly, I. Huynen, C. J. M. S. Detrembleur, and E. R. Reports, Polymer/carbon based composites as electromagnetic interference (EMI) shielding materials, 74, 211–232, (2013).

A. Kausar, I. Rafique, B. J. P.-P. T. Muhammad, and Engineering, Electromagnetic interference shielding of polymer/nanodiamond, polymer/carbon nanotube, and polymer/nanodiamond–carbon nanotube nanobifiller composite: a review, 347–363, (2017).

R. K. Mishra, M. G. Thomas, J. Abraham, K. Joseph, S. J. A. M. f. E. S. F. Thomas, Properties, and Applications, Electromagnetic interference shielding materials for aerospace application: A state of the art, pp. 327–365, (2018).

K. Katoch, N. Jaglan, S. D. Gupta, M. S. J. I. J. o. R. Sharawi, and M. C. A. Engineering, Design of a triple band notched polarization independent compact FSS at UWB frequency range, (2021).

A. A. M. Rahman, M. T. Islam, M. Moniruzzaman, H. Alsaif, A. A. Maash, M. M. Hasan, and M. S. J. I. J. o. O. Soliman, Resonator-based near perfect metamaterial absorber with high EMI shielding for Wi-Fi and 5G applications, vol. 18, no. 1, pp. 2375497, (2024).

S. K. Dhawan, A. P. Singh, and A. Ohlan, Smart Materials Design for Electromagnetic Interference Shielding Applications, (2022).

Q. Wei, S. Pei, X. Qian, H. Liu, Z. Liu, W. Zhang, T. Zhou, Z. Zhang, X. Zhang, and H. M. J. A. M. Cheng, Superhigh electromagnetic interference shielding of ultrathin aligned pristine graphene nanosheets film, 1907411, (2020).

Ramachandran, T., Faruque, M. R. I., Siddiky, A. M. & Islam, M. T. Reduction of 5G cellular network radiation in wireless mobile phone using an asymmetric square shaped passive metamaterial design. Sci. Rep. 11(1), 2619 (2021).

Bakır, M. et al. Metamaterial-based energy harvesting for GSM and satellite communication frequency bands. Opt. Eng. 57(8), 087110–087110 (2018).

Rahman, A. A. M. et al. Triple band frequency tunable polarization insensitive metamaterial absorber for WLAN and 5G applications. Opt. Mater. 145, 114368 (2023).

Dhillon, A. S., Mittal, D. & Bargota, R. Triple band ultrathin polarization insensitive metamaterial absorber for defense, explosive detection and airborne radar applications. Microw. Opt. Technol. Lett. 61(1), 89–95 (2019).

Jafari, F. S., Naderi, M., Hatami, A. & Zarrabi, F. B. Microwave Jerusalem cross absorber by metamaterial split ring resonator load to obtain polarization independence with triple band application. AEU-Inter. J. Electron. Commun. 101, 138–144 (2019).

Wei, Y. et al. A multiband, polarization-controlled metasurface absorber for electromagnetic energy harvesting and wireless power transfer. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Tech. 70(5), 2861–2871 (2022).

S. A. Mohammed, R. A. K. Albadri, and K. S. L. Al-Badri, Simulation of the microwave five-band a perfect metamaterial absorber for the 5G commmunication, Heliyon, (2023).

Singh, R. K. & Gupta, A. A wrenched-square shaped polarization independent and wide angle stable ultra-thin metamaterial absorber for S-band, X-band and Ku-band applications. AEU-Inter. J. Electron. Commun. 132, 153648 (2021).

S. A. Naqvi, M. A. Baqir, G. Gourley, A. Iftikhar, M. Saeed Khan, and D. E. Anagnostou, A novel meander line metamaterial absorber operating at 24 GHz and 28 GHz for the 5G applications, Sensors, vol. 22, no. 10, pp. 3764, (2022).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2025R826), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Md.M. contributed to the conception, design, data collection, analysis, simulation, and writing of the original manuscript. S.L. contributed to the conception, design, analysis, and completion of the writing and presentation of the whole manuscript. M.M. contributed to the analysis and the writing and presentation of the whole manuscript. N.M.J. contributed to the analysis and the writing and presentation of the whole manuscript. S.S.A. contributed to the analysis and the writing and presentation of the whole manuscript. M.T.I. contributed to the analysis and the writing and presentation of the whole manuscript. Md.S. contributed to the analysis and the writing and presentation of the whole manuscript. S.S.A. contributed to the conception, design, data collection, analysis, simulation, and writing of the original manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Moniruzzaman, M., Larguech, S., Mobarak, M. et al. Dual band polarization insensitive metamaterial absorber for EMI shielding from GSM and 5G communication systems. Sci Rep 15, 12292 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96507-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96507-4

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Spectral Performance in Quad-Band Satellite Communication with Triangular Ring Structures

Journal of Electronic Materials (2026)

-

High-performance metamaterial absorber for electromagnetic interference shielding at X-band frequencies

Optical and Quantum Electronics (2025)

-

Electromagnetic Characterization of a Wideband Nanoscale Metamaterial Absorber for Ultraviolet Radiation Shielding

Silicon (2025)