Abstract

This study investigated the clinical efficacy and psychological effects of the femoral neck system (FNS) combined with recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 (rhBMP-2) and cannulate compression screw (CCS) in treating unstable femoral neck fractures in young adults. We conducted a retrospective analysis of clinical data from 61 patients with femoral neck fractures who met our selection criteria and were admitted to our hospital between December 2019 and 2022. Patients were divided into two groups based on their internal fixation. Group A received hollow compression screw fixation, whereas Group B underwent FNS combined with rhBMP-2 fixation. We recorded preoperative and last follow-up scores on the self-rating depression scale (SDS) and self-rating anxiety scale (SAS), along with surgery duration, intraoperative fluoroscopy frequency, blood loss, postoperative recovery, and complication rates for both groups. Routine postoperative radiographs were used to evaluate fracture reduction and internal fixation, while Harris scores were used to assess hip joint function. Both groups were followed up for 7–38 months, averaging 25.25 ± 7.62 months. However, intraoperative blood loss was significantly lower in Group A than in Group B, and Group A experienced significantly more fluoroscopy sessions (P < 0.05). In Group A, complications included six cases of nail retraction, three cases of femoral neck shortening, four cases of femoral head necrosis, and one case of bone nonunion. At the last follow-up, femoral neck shortening differed significantly from that in the healthy side (P < 0.05), as did femoral eccentricity (P < 0.05). In Group B, there were three cases of femoral neck shortening, including one nonunion, and four cases of femoral head necrosis. No significant differences in femoral neck shortening were observed compared to the healthy side (P > 0.05), and no significant change was seen in femoral eccentricity from the first to the last follow-up (P > 0.05). Preoperatively, no significant differences in femoral neck shortening and eccentricity were found between the two groups (P > 0.05). Both groups demonstrated good recovery in hip joint function. However, there were significant differences preoperatively and in the last follow-up SDS and SAS scores (P < 0.05). The combination of FNS and rhBMP-2 for treating femoral neck fractures is minimally invasive and easy to perform and offers greater stability. This approach promotes fracture healing with minimal irritation to surrounding muscles and soft tissues, facilitating early weight-bearing and functional rehabilitation. Both surgical methods effectively enhance the psychological well-being of patients with femoral neck fractures who experience anxiety and depression, thereby improving their quality of life and achieving satisfactory short-term therapeutic outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In systemic fractures, femoral neck fractures (FNFs) represent approximately 3.58% of cases1. The rapid advancement in modern industry and transportation has led to an increase in FNFs, primarily caused by high-energy injuries. These fractures are characterized by significant vertical shear forces and are constrained by the unique functional anatomy of the femoral neck. Healing rates for FNFs are lower, with a nonunion rate of approximately 9.3%. Furthermore, due to the specialized blood supply to the femoral head, complications such as femoral head collapse and ischemic necrosis can occur in up to 14.3% of patients2. Despite various treatment options available for FNFs, comprehensive and systematic management remains elusive. Young adults, who bear greater social responsibilities, face substantial impacts on their quality of life and mental health if fractures do not heal or if femoral head necrosis occurs3. Addressing effective treatment strategies for FNFs has become an urgent clinical challenge. With advancements in medical practice, surgical intervention is generally recommended for FNFs. Common surgical approaches include fracture reduction and internal fixation, as well as hip replacement surgery. Currently, two major challenges persist in the clinical treatment of FNFs: nonunion and ischemic necrosis. Internal fixation remains the primary treatment option for young adults and encompasses two prevalent techniques. The dynamic hip system offers mechanical stability but is associated with significant trauma, prolonged surgical duration, and operational complexity. By contrast, the dilated compression screws (CCS) represent a minimally invasive alternative; however, their insufficient mechanical stability necessitates extended bed rest and crutch use postoperatively, prolonging recovery time. Reported complication rates for dynamic hip screws are 46.7%, with a reoperation rate of 22%, whereas CCS rates are 35.1% and 20%, respectively4. The femoral neck system (FNS) is the latest minimally invasive solution for FNFs, integrating the benefits of hollow screw techniques and the mechanical stability of the dynamic hip system. This method is easy to perform and provides excellent mechanical support. Although FNS has been widely implemented in clinical practice for treating FNFs, reports on its use in conjunction with rhBMP-2 for young adults are limited. Additionally, the psychological status of young adults has not received adequate attention. Therefore, this study aimed to compare the clinical efficacy and psychological effects of FNS combined with rhBMP-2 against traditional hollow compression screw fixation for FNFs.

Methods

General information

Our study collected data from 61 cases of FNFs treated at the Department of Orthopedics of Fuyang People’s Hospital, affiliated with Anhui Medical University, from December 2019 to December 2022. Patients were randomly assigned to two groups: Group A, which received treatment with hollow screws, included 18 males and 13 females. Group B, which received FNS treatment, comprised 16 males and 14 females (Supplementary Table). All patients underwent preoperative radiography and 3D CT examinations to confirm the diagnosis of FNFs. Inclusion criteria were as follows: age under 60 years; FNF within 3 weeks of injury; treatment with FNS combined with rhBMP-2 or hollow screw internal fixation; and complete follow-up data. Exclusion criteria included pathological fractures, severe osteoporosis, mental health conditions, and metabolic disorders that contraindicate surgery. This study received approval from the Ethics Committee of our hospital ([2022]31).

Surgical methods

Group A hollow nail internal fixation

The patient was positioned supine on a bone traction bed to facilitate fracture reduction, which was confirmed as satisfactory through fluoroscopy. Routine disinfection was performed, and three guide needles were inserted percutaneously, with fluoroscopy confirming their optimal placement. Using a hollow drill bit, small inverted cross-shaped incisions were made to create drill holes. Three hollow nail screws were then tapped and screwed in, achieving proper alignment, followed by closure of the incisions.

Group B FNS combined with rhBMP-2 internal fixation

The patient was maintained in a supine position, and a traction bed was set up. C-arm fluoroscopy indicated effective fracture reduction. Standard surgical disinfection was conducted, with needle insertion targeted at the level of the lesser trochanter, creating an incision approximately 5 cm in length. The incision was made layer by layer, ensuring an appropriate forward inclination angle of the neck-shaft. A guide needle was inserted through the guide sleeve, and a frontal view confirmed its placement within the middle and lower third of the femoral neck. A lateral view was obtained, and the guide needle channel was enlarged using a trapezoidal drill. Depth was measured, after which the FNS power cross nail system’s femoral neck power rod was inserted. A locking screw was used to fix the femoral neck power rod, and rhBMP-2 was implanted into the FNF site using a hollow depth gauge (Fig. 1). An anti-rotation screw was then inserted into the femoral neck power rod and gradually compressed. Re-examination indicated successful fracture reduction, and the FNS power cross nail system was utilized. The wound was thoroughly rinsed to control bleeding, followed by layered suturing and sterile dressing application.

Postoperative management: All patients were administered anticoagulant therapy within 24 h post-surgery to prevent deep vein thrombosis in the lower limbs, as well as antibiotic therapy to reduce the risk of infection. Rehabilitation therapists initiated rehabilitation exercises.

Observation indicators

Preoperative and postoperative assessments included recording the SDS and SAS scores for two patient groups. Surgical metrics recorded were operative time, intraoperative fluoroscopy frequency, intraoperative blood loss, fracture healing time, changes in femoral eccentricity between the affected and healthy sides, and complications such as femoral neck shortening (Fig. 2) and femoral head necrosis. Postoperative routine radiography examinations were performed to evaluate fracture reduction and internal fixation, with Harris scores utilized to assess hip joint function.

Radiograph of the pelvic anterior posterior position showing measurements of shortening and femoral offset (FO). The axis of the femoral shaft (c) is perpendicular to the midpoint of the femoral medullary cavity (a, b), and the distance perpendicular to (c) through the center of the femoral head (d) is measured. The measurement of the distance (h) between the center of the femoral head (e) and the upper edge of the lesser trochanter perpendicular to the femoral axis (c) is labeled as (f). FO (g) is the vertical distance between the center of rotation of the femoral head (d) and the central axis of the femoral shaft (c).

Statistical analysis

Data for this study were independently entered into an Excel spreadsheet by two individuals and analyzed using SPSS 26.0 statistical software. Count data were expressed as percentages and analyzed using the χ2 test, whereas measurement data were reported as (x ± s) and analyzed using the t-test. A p-value of < 0.05 was deemed statistically significant.

Results

According to the Garden classification, Group A were 5 type I fractures, 6 type II fractures, 14 type III fractures, and 5 type IV fractures. Age ranged from 24 to 52 years, with an average of 39.55 ± 8.29 years. Group B with 4 type I, 7 type II, 13 type III, and 6 type IV fractures. Patient age in this group ranged from 25 to 52 years, averaging 36.33 ± 7.02 years. No statistically significant differences were found in demographic variables, such as age and gender, between the two groups (p > 0.05; Table 1).

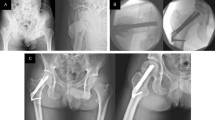

Intraoperative blood loss was significantly lower in Group A than in Group B, and Group A experienced significantly more fluoroscopy sessions (p < 0.05; Fig. 3). As for complications, Group A comprised six cases of nail retraction, three cases of femoral neck shortening, four cases of femoral head necrosis, and one case of bone nonunion (Table 2). By contrast, Group B comprised three cases of femoral neck shortening, including one nonunion and four instances of femoral head necrosis. Both groups demonstrated good recovery in hip joint function (Fig. 4). However, there were significant differences in preoperative and last follow-up SDS and SAS scores (p < 0.05; Fig. 5). At the last follow-up, femoral neck shortening differed significantly from the healthy side (p < 0.05), as did femoral eccentricity (p < 0.05; Fig. 6). No significant differences in femoral neck shortening were observed compared with the healthy side (p > 0.05), and no a significant change was seen in femoral eccentricity from the first to the last follow-up (p > 0.05). Preoperatively, no significant differences in femoral neck shortening and eccentricity were found between the two groups (p > 0.05; Fig. 7). Preoperative and postoperative radiography imaging findings and postoperative follow-up hip joint function of CCS (Fig. 8) and FNS (Fig. 9) surgical methods were assessed.

(A) Preoperative pelvic anterior and posterior radiographs suggesting femoral neck fracture (B) Postoperative radiography measurement of (g) and (h) values in CCS imaging (C) In CCS patients, there was a difference in femoral neck shortening when compared with that of the healthy side at the last follow-up (p = 0.034), and there was also a difference in femoral eccentricity (p = 0.012).

(A) Preoperative pelvic anterior posterior radiographs of femoral neck fracture (B) FNS combined with rhBMP-2 postoperative imaging radiograph measurement of (g) and (h) values (C) Comparison of the radiographs of the injured and healthy sides. Femoral neck shortening of FNS patients at the first and last postoperative follow-up. Femoral offset of FNS patients at the first and last postoperative follow-ups, CCD angle of FNS patients at the first and last postoperative follow-up. (C) In patients with FNS combined with rhBMP, there was no significant difference in femoral neck shortening at the last follow-up compared with that of the healthy side (P = 0.689), and there was no significant difference in femoral eccentricity between the first and last follow-up after surgery (P = 0.736).

CCS group: male, 30 years old, with a right femoral neck fracture, Garden III type, Preoperative radiographs of (A,B) showed a right femoral neck fracture; (C,D) show immediate postoperative radiographs, indicating good reduction of the fracture The fixed position inside CCS is good; (E,F) show radiographs taken 2 years after surgery, indicating that the fracture has healed. (G,H) show good hip joint function.

FNS group: male, 33 years old, with a right femoral neck fracture, Garden III type. (A) shows a preoperative X-ray of the right femoral neck fracture; (B,C) show immediate postoperative X-ray images, indicating good reduction of the fracture FNS internal fixation position is good; (D,E) show X-ray images taken 2 years after surgery, indicating that the fracture has healed. (E,F) show good hip joint function.

Discussion

High-energy injuries are increasingly common among young adults in clinical practice. In patients aged 18–60 years, these injuries typically manifest as unstable FNFs5,6. Two significant challenges in managing these fractures—non-union and ischemic necrosis of the femoral head—remain unresolved. The emergence of high-energy trauma has led to an increasing incidence of FNFs, particularly affecting young patients, who experience more severe damage and higher complication rates, ultimately impacting their quality of life. For young adults, fracture reduction and internal fixation are the most widely accepted treatments. However, surgical interventions still carry a substantial risk of complications, including nail retraction, femoral head necrosis, non-union, and femoral neck shortening. Achieving anatomical reduction and stable internal fixation is critical to mitigate these risks.

In our study, we compared outcomes between two groups: the CCS group, which exhibited six cases of femoral neck shortening, four cases of femoral head necrosis, and one case of bone non-union, and the FNS combined with rhBMP-2 group, which had only three cases of femoral neck shortening, one case of non-union, and four cases of femoral head necrosis, with no instances of nail retraction. In young and middle-aged patients with FNFs, displacement and reduction of the fracture are key factors influencing postoperative complications. Different internal fixation methods can also significantly affect treatment outcomes7. Current clinical practice offers various internal fixation devices8. FNFs in young adults, often resulting from high-energy injuries, present challenges due to their instability and complexity9. Traditional CCS internal fixation has a high failure rate6, and our study indicates a greater incidence of complications associated with this method. Xia et al.10 reported a higher removal rate for hollow screws post-surgery, while Ma et al.11 highlighted that CCS offers advantages over DHS in terms of blood loss, incision length, duration of surgery, and hospitalization. They contend that CCS is more minimally invasive than DHS, but biomechanically, it exhibits lower mechanical strength12. By contrast, the combination of FNS and rhBMP-2 not only avoids nail retraction but also leads to fewer complications than CCS. FNS represents a minimally invasive approach to FNFs, leveraging the benefits of hollow screw technology and the mechanical stability of dynamic hip systems. It is user-friendly and minimizes invasiveness while ensuring adequate mechanical support.

During clinical treatment, the psychological well-being of patients is often overlooked. Literature indicates that patients with fracture are particularly susceptible to psychological disorders13. In response, we conducted a questionnaire survey among participants in this study. Most patients reported feeling emotionally depressed before surgery, frequently experiencing sadness and heightened anxiety. This emotional state may stem from the significant social responsibilities borne by young adults, who constitute the majority of the workforce14. The results of the preoperative questionnaire, along with the significance of SDS and SAS scores15, revealed mild depression and anxiety among patients before surgery. Notably, follow-up assessments showed significant improvements in SDS and SAS scores postoperatively, suggesting that surgical intervention can alleviate some psychological distress. However, this improvement also relates to comprehensive support measures, including psychological counseling and self-regulation strategies for patients16. Regarding the changes in psychological aspects, patients have certain levels of depression and anxiety before surgery. Through this study, different surgical plans can improve and alleviate the psychological state of patients. For such patients with preoperative depression and anxiety, appropriate preoperative intervention can promote the prognosis of patients. Through this study, can we provide preoperative psychological intervention to patients so that they no longer have doubts about surgery and future rehabilitation.

In this study, we measured the femoral offset (FO) and the center of rotation of the femoral head perpendicularly to the anatomical axis of the femur, at the upper edge of the lesser trochanter. The femoral offset reflects the force arm of the abductor muscle and is crucial for understanding the recovery of lower limb length post-surgery17. The center of rotation provides a specific and intuitive insight into femoral neck shortening relative to the anatomical axis. The average healing time for fractures in the CCS group was 4.09 months, compared with that of 3.62 months in the FNS group. The incidence of complications in CCS surgery included retreat nail (19.4%), femoral head necrosis (16.1%), nonunion (6.5%), and femoral neck shortening (16.1%). By contrast, FNS combined with rhBMP-2 treatment showed incidence rates of 0% for retreat nail, 13.3% for femoral head necrosis, 3.3% for nonunion, and 10% for femoral neck shortening. The three hollow screws used in CCS exert pressure on fractures, promoting healing while occupying a relatively small area in the femoral neck. This design minimizes interference with blood flow in the femoral head and neck and creates a triangular distribution of forces that can reduce stress on femoral head rotation. Such configuration enhances contact between fracture ends, facilitating healing. However, the effectiveness of these screws can be compromised by both subjective and objective surgical factors, resulting in poor resistance to vertical shear and torsion. This may lead to loosening, displacement of fracture ends, nonunion of the femoral head, and shortening of the femoral neck18,19. Our study found that the incidence of femoral neck shortening in the FNS group was significantly lower than in the CCS group, likely due to FNS’s superior mechanical stability and shear resistance20. Nail retraction is a common complication, affecting 14.5% of patients, with non-parallel and widely distributed screw trajectories potentially leading to complications during the healing of osteoporotic FNFs21. Notably, no patients in the FNS group experienced screw retraction due to the locking mechanism of the steel plate and screws. Femoral neck shortening and hip joint dysfunction can occur in patients with FNFs after CCS treatment22,23. Weil et al.24 demonstrated that inadequate reduction of FNFs directly contributes to postoperative femoral neck shortening. Osteoporosis can decrease grip and stress resistance at the fracture site, leading to reduced stability and increased likelihood of shortening25. In our study, both CCS and FNS groups achieved satisfactory functional outcomes, with no statistically significant difference in postoperative Harris Hip Scores (HHS). Both types of internal fixation yielded similar clinical results regarding HHS11. Clinical experience suggests that FNS exerts greater pressure on the fracture site than CCS26,27. Factors influencing clinical outcomes in FNFs fixation primarily include patient condition, fracture displacement degree, internal fixation adequacy, and the quality of surgical reduction.

The FNS is an innovative femoral neck fixation system. Clinical studies indicate that the biomechanical strength of the FNS internal fixation system is twice that of traditional hollow nail systems26,28. Compared with dynamic hip screws, the FNS provides a 40% improvement in anti-rotation stability, features fewer implant footprints, and avoids lateral protrusion in the first 15 mm of controlled retraction screws, thereby reducing soft tissue stimulation. Biomechanically, the risk of subtrochanteric fractures with the FNS is lower than that associated with hollow screw systems and DHS during gait and lateral drop loads. However, when the femoral neck is shortened, CCS and DHS devices may retract laterally, leading to soft tissue irritation and pain on the outer thigh29. Our use of FNS in conjunction with rhBMP-2 stems from clinical practice aimed at enhancing fracture healing rates, resulting in favorable clinical outcomes.

The application of FNS for femoral neck fractures represents a significant advancement in minimally invasive surgery and accelerated rehabilitation, minimizing surgical trauma while ensuring secure internal fixation. Early mobilization can reduce hospitalization and rehabilitation duration, aligning with the ERAS principles of rapid recovery30. As this technology continues to be promoted and adopted, it will open new avenues for improved patient prognoses.

Despite these promising results, our study has limitations, which are as follows: (1) the relatively short clinical application time of FNS combined with rhBMP-2 has resulted in a limited sample size; (2) our analysis only compares the FNS combined with rhBMP-2 group to the CCS group; a simultaneous comparison with the FNS group may yield more robust findings; (3) we only examined changes in patients’ psychological states pre- and post-surgery; providing appropriate psychological interventions could enhance postoperative outcomes.

Conclusions

In summary, FNS demonstrates excellent biomechanical properties and superior overall structural stability. Young and middle-aged patients with FNFs can achieve satisfactory clinical outcomes through either CCS or FNS combined with rhBMP-2 treatment, effectively improving psychological well-being, enhancing self-management, and elevating quality of life for those experiencing anxiety and depression. FNS combined with rhBMP-2 offers a minimally invasive surgical option that is easy to perform, promotes better stability, reduces nonunion rates in femoral neck fractures, and facilitates early weight-bearing and functional exercises, representing a novel approach to managing FNFs.

Data availability

The corresponding author can provide the datasets generated and analyzed during the current study upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CCS:

-

Cannulate compression screw

- FNF:

-

Femoral neck fracture

- FNS:

-

Femoral neck system

- FO:

-

Femoral offset

- HHS:

-

Harris hip score

- SAS:

-

Self-rating anxiety scale

- SDS:

-

Self-rating depression scale

References

Florschutz, A. V. et al. Femoral neck fractures: current management. J. Orthop. Trauma 29 (3), 121–129 (2015).

Slobogean, G. P. et al. Complications following young femoral neck fractures. Injury 46 (3), 484–491 (2015).

Achwieja, E. et al. The association of mental health disease with perioperative outcomes following femoral neck fractures. J. Clin. Orthop. Trauma 10 (1), S77–S83 (2019).

FAITH-2 et al. Fixation using alternative implants for the treatment of hip fractures (FAITH-2): design and rationale for a pilot multi-centre 2×2 factorial randomized controlled trial in young femoral neck fracture patients. Pilot Feasibil. Stud. 5, 70 (2019).

Medda, S., Snoap, T. & Carroll, E. A. Treatment of young femoral neck fractures. J. Orthop. Trauma 33 (1), S1–S6 (2019).

Liporace, F. et al. Results of internal fixation of pauwels type-3 vertical femoral neck fractures. J. Bone Joint Surg. (Am.) 90 (8), 1654–1659 (2008).

Stockton, D. J. et al. Failure patterns of femoral neck fracture fixation in young patients. Orthopedics 42 (4), e376–e380 (2019).

Panteli, M., Rodham, P. & Giannoudis, P. V. Biomechanical rationale for implant choices in femoral neck fracture fixation in the nonelderly. Injury 46 (3), 445–452 (2015).

Han, Z. et al. Multiple cannulated screw fixation of femoral neck fractures with comminution in young- and middle-aged patients. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 17 (1), 280 (2022).

Xia, Y. et al. Treatment of femoral neck fractures: sliding hip screw or cannulated screws? A meta-analysis. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 16 (1), 54 (2021).

Ma, J. X. et al. Sliding hip screw versus cannulated cancellous screws for fixation of femoral neck fracture in adults: A systematic review. Int. J. Surg. 52, 89–97 (2018).

Bliven, E. et al. Biomechanical evaluation of locked plating fixation for unstable femoral neck fractures. Bone Joint Res. 9 (6), 314–321 (2020).

Cristancho, P., Lenze, E. J. & Avidan, M. S. Trajectories of depressive symptoms after hip fracture. Psychol. Med. 46 (7), 1413–1425 (2016).

Faravelli, C. et al. Gender differences in depression and anxiety: the role of age. Psychiatr. Res. 210 (3), 1301–1303 (2013).

Philippot, A. et al. Impact of physical exercise on depression and anxiety in adolescent inpatients: A randomized controlled trial. J. Affect. Disord. 301, 145–153 (2022).

Lim, K. K. et al. The role of prefracture health status in physical and mental function after hip fracture surgery. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 19 (11), 989–994 (2018).

Niemann, M. et al. Restoration of hip geometry after femoral neck fracture: A comparison of the femoral neck system (FNS) and the dynamic hip screw (DHS). Life (Basel) 13 (10), 2073 (2023).

Ugat, P., Bliven, E. & Hackl, S. Biomechanics of femoral neck fractures and implications for fixation. J. Orthop. Trauma 33 (1), S27–32 (2019).

Hu, D. P. et al. Dynamic compression locking system versus multiple cannulated compression screw for the treatment of femoral neck fractures: a comparative study. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 21 (1), 230–1112 (2020).

Stoffel, K. et al. Biomechanical evaluation of the femoral neck system in unstable Pauwels III femoral neck fractures: a comparison with the dynamic hip screw and cannulated screws. J. Orthop. Trauma 31 (3), 131–137 (2017).

Wu, Y. et al. Screw trajectory affects screw cut-out risk after fixation for nondisplaced femoral neck fracture in elderly patients. J. Orthop. Surg. Hong Kong 27 (2), 230949901984025 (2019).

Wang, C. T. et al. Suboptimal outcomes after closed reduction and internal fixation of displaced femoral neck fractures in middle-aged patients: is internal fixation adequate in this age group? BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. D 19 (1), 190 (2018).

Haider, T. et al. Femoral shortening does not impair functional outcome after internal fixation of femoral neck fractures in non-geriatric patients. Arch. Orthop. Trauma Surg. 138 (11), 151 (2018).

Weil, Y. A. et al. Femoral neck shortening and varus collapse after navigated fixation of intracapsular femoral neck fractures. J. Orthop. Trauma 26 (1), 19–23 (2012).

Sung, Y. B. et al. Risk factors for neck shortening in patients with valgus impacted femoral neck fractures treated with three parallel screws: is bone density an affecting factor? Hip Pelvis 29 (4), 277–285 (2017).

Schopper, C. et al. Higher stability and more predictive fixation with the femoral neck system versus Hansson pins in femoral neck fractures Pauwels II. J. Orthop. Translat. 24, 88–95 (2020).

Cha, Y. et al. Pre-sliding of femoral neck system improves fixation stability in Pauwels type III femoral neck fracture: a finite element analysis. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 24 (1), 506 (2023).

Hu, H. et al. Clinical outcome of femoral neck system versus cannulated compression screws for fixation of femoral neck fracture in younger patients. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 16 (1), 370 (2021).

Enocson, A. & Lapidus, L. J. The vertical hip fracture-a treatment challenge. A cohort study with an up to 9 year follow-up of 137 consecutive hips treated with sliding hip screw and antirotation screw. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 13, 171 (2012).

Long, X. et al. Enhanced recovery after surgery speeds up healing for hip fracture patients. Am. J. Transl. Res. 16 (7), 3231–3239 (2024).

Acknowledgements

We thank the authors of the included studies for their help.

Funding

This study was supported by the Anhui Medical University Research Fund Project (2021xkj208), and the Anhui Provincial Department of Science and Technology project (202304295107020118), and the Anhui Spinal Deformity Clinical Medical Research Center Innovation Fund Project (AHJZJX-GG2023-005).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YHY participated in design of the study, data analysis, and drafting the manuscript. LD conceived of the study, data analysis, drafting the manuscript and commented on the paper.YWR, PT and LYF participated in the design of the study and statistical analysis. LHT and LDD participated in design of the study and data analysis. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board and the Ethics. Committee of Our Hospital ([2022]31). We also followed the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients gave their informed consent prior to their inclusion in the study. The current study was approved by the ethical committee of Affiliated Fuyang People’s Hospital of Anhui Medical University before data collection and analysis. Written informed consent to participate was obtained from all participants.

Consent for publication

Patients signed informed consent regarding publishing their data.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, D., Yang, W., Pan, T. et al. Comparative study of rhBMP-2 assisted femoral neck system and cannulated screws in femoral neck fractures: clinical efficacy and psychological status. Sci Rep 15, 12625 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96635-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96635-x

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Pharmacodynamics study of remimazolam besylate in anxious patients undergoing gastroscopy: a biased-coin design up-and-down sequential allocation trial

BMC Anesthesiology (2025)

-

Psychological safety and its influencing factors among elderly patients following traumatic fracture surgery: a cross-sectional study

BMC Geriatrics (2025)