Abstract

In the conventional radial uncoupled charge single free surface blasting, the bottom rock mass is difficult to be fully broken, which affects the blasting effect and restricts the tunneling efficiency. This difficulty adversely impacts the blasting outcome and limits the efficiency of excavation. To address this issue, this paper proposes a solution that involves modifying the charge structure to implement a variable diameter decoupled charge, and it analyzes the theoretical feasibility of this approach. The variably diameter decoupled charge and radial decoupled charge single-hole blasting model was established and compared using LS-DYNA. Furthermore, the effects of various parameters on the rock-breaking efficiency of variable diameter decoupled charges were analyzed. The results show that, in comparison to radially decoupled charges, variable diameter decoupled charges exhibit a greater explosive mass at their base. This enhancement leads to an increase in the effective stress on the surrounding rock, thereby effectively addressing the issue of inadequate fragmentation of the rock mass at the base of radially decoupled charges. Simultaneously, the directional effect of stress wave superposition and the balancing effect of the cavity on internal pressure contribute to an increase in the effective stress and reflected tensile stress of the overlying rock mass. This phenomenon ensures that effective fragmentation of the overlying rock mass can still be achieved, even with a relatively small amount of explosive charge. Under the condition of maintaining the same charge weight and borehole diameter, increasing the length and radius of the expanding section of the explosive significantly impacts rock fragmentation, whereas reducing the radius of the contracting section has a minimal effect. In engineering applications with a common borehole diameter of 4.2 cm, when the length of the expanding section of the explosive charge is half of the total charge length and the radius of the expanding section ranges from 1.65 cm to 1.70 cm, more effective rock fragmentation at the bottom can be achieved, resulting in an overall favorable fragmentation outcome.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The drilling and blasting method is the most commonly used technique for underground excavation. The focus of underground blasting excavation lies in the effective fragmentation of the rock mass, to enhancing the efficiency of excavation. In terms of the explosion source, the main factors affecting the rock breaking effect are the burden1, the length of the stemming2,3 and the charge structure4. In conventional blasting, specifically full-coupling charge blasting, a substantial amount of energy generated during the explosion is utilized to form the fragmentation zone, while only a small fraction of the energy is employed to create fractures for cutting the rock, decoupled charging technology has become widely used. This is because it effectively reduces the impact of the blasting gases immediate expansion.

Decoupled charge is mainly divided into axial decoupled charge and radial decoupled charge. The axial decoupled charge air deck facilitates the generation of repeated shock waves, which interact with the rock for an extended duration, thereby enhancing the efficacy of the fracture process5.The location of the air desk is a key factor in its need to be determined6, when the air desk is located at the top7, the middle8, and the bottom9, different rock crushing effects can be obtained, which are applied in different blasting scenarios. In addition, multi-segment air desk and water desk are also used10,11. The filling medium in the radial uncoupling charge acts as a buffer, it attenuates the transmission of blasting energy. This helps to prevent the formation and growth of the crushing zone. The reasonable decoupling coefficient can make the energy carried by the bursting cracks more concentrated, increase the range of the fracture zone, and improve the crushing effect12, so the filling medium and the uncoupling rate are the key factors affecting the effect of the uncoupling charge blasting13,14,15, and they mainly cause the well-wall the peak pressure and loading rate of the pressure are different16,17,18. Compared to fully coupled charge blasting, decoupled charge blasting reduces the peak pressure in the borehole wall and prolongs the duration of blast loading19. It can be seen that the factors affecting the effect of decoupled charging on rock crushing can be attributed to the changes in cavity position, shape and material properties, and by adjusting the charging position and cavity volume in the cavity charging structure, the temporal and spatial effects of the blast stress wave and blast gas can be fully utilized to achieve controllable rock crushing20.

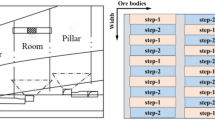

The above research has analyzed the mechanism and key parameters of radial and axial decoupled charge, which contributes to the realization of efficient crushing of the rock mass. however, due to the existence of a time difference in the column packet detonation, resulting in differences in the superposition of the stress field at different locations in the rock mass. For the underground blasting project is often used to the bottom of the detonation, the interval distance between the surface of the stress wave wavefront along the direction of the detonation is relatively small, and the time difference is shorter, stress Superposition in the direction of detonation of the blast wave is stronger21. While the stress wave in the free surface of the reflection phenomenon will occur, resulting in the side of the rock adjacent to the free surface of the other side of the greater stress, as shown in Fig. 1. In addition, the rock at the bottom is more difficult to be broken due to the greater use of clamping. Therefore, it often results in the rock at the free surface being broken more fully, while the rock at the bottom cannot be effectively broken, forming the phenomenon of under excavation at the root. If the top detonation method is used, it will lead to insufficient crushing of the rock in the hole, resulting in a large rock mass, which is also not conducive to rock throwing and the formation of the slot cavity22.

The simplest and most direct way to solve this problem is to strengthen the charge at the bottom of the bag, at which time the charge structure becomes a variable diameter decoupled charge. However, in the actual project, the amount of charge in the hole is strictly limited, and increasing the amount of charge will lead to excessive vibration and increase the safety risk. Therefore, it is necessary to study in the same charge, the use of variable diameter decoupled charge can be solved in the radial decoupled charge in the single free-face blasting of the bottom of the rock is not broken sufficiently, as well as at the same time to ensure that the overall effect of rock crushing. It is worth mentioning that there are few studies related to variable diameter decoupled loads in the existing literature. Therefore, in this paper, firstly, the theoretical calculation of the stress field is performed using the iterative method. This method involves an equivalent unit spherical drug charge. The aim is to analyze the theoretical viability of a variable diameter decoupled charge. Then the parameters of the RHT ontological model of the rock that has been verified are used to establish the single-hole blasting models, which include radial uncoupling charge and variable diameter uncoupling charge under a single free surface. To verify the high efficiency of the variable diameter uncoupling charge in breaking the rock, comparing the damage distributions between the two. Further analyze the influence of the dimensional parameters of the variable diameter uncoupling charge.

Variable diameter decoupled charge stress analysis

The variable diameter charging structure is shown in Fig. 2(b), by distributing part of the charge from the upper part of the radially decoupled charge to the lower charge, and named them respectively as the reduced-segment and expanded-segment charges, in Fig. 2(a). The charge volume of the two charging structures should be consistent,

which,

where H0 is the charge length of radial decoupled charge; r0 is the charge radius of radial decoupled charge; r1 is the charge radius of reduced section of variable diameter decoupled charge; H1 is the charge length of reduced section of variable diameter decoupled charge; r2 is the charge radius of enlarged section of variable diameter decoupled charge; and H2 is the charge length of enlarged section of variable diameter decoupled charge.

For the columnar pill pack, its stress field distribution is often calculated by the equivalent unit ball pill pack iteration method23, which is based on the principle of dividing the columnar pill pack into a finite number of unit ball pill packs with equivalent radii, and obtaining the stress wave excited by the whole column based on the iteration of the stress wave of each unit ball pill pack. Through the unit-column and unit-sphere equivalent volume relationship, it can be obtained that

where re1, re2 are the equivalent unit spherical packet radii of the reduced and expanded segment packets, respectively.

For the decoupled charge, it is assumed that the expansion process of the gas produced by detonation is an isentropic expansion process, the hole-wall pressure generated during the bursting of a unitary spherical charge packet24 is:

where Pd is the initial impact pressure on the wall of the borehole; ρe is the density of explosives; D is the blast velocity of explosives; k is the isentropic expansion index, generally take k = 3; n is the impact shock wave and the borehole wall interaction with the impact multiplier, generally take n = 8 ~ 11; de is the diameter of the packet; db is the diameter of the borehole.

During the propagation of the stress wave in the rock mass, it continuously decays with the increase of propagation distance, and its decay law25 is:

where P(R) for the distance from the explosive source of pressure at R; r for the relative distance, r = R/re, R is the center of the blast distance, re is the radius of the charge; α is the attenuation factor, α = 2 ± μd / (1-μd), The positive and negative signs correspond to the shock wave region and stress wave region, respectively. μd is the dynamic Poisson’s ratio of the rock mass, and in the loading range of engineering blasting, it can be assumed that μd = 0.8μ, and μ is the static Poisson’s ratio of the rock mass.

Assuming that the propagation medium of the explosion stress wave is homogeneous and isotropic, the stress wave of the unitary spherical packet is a spherical wave, and therefore the shape of its stress wave is a gradually decaying sinusoidal wave26:

where t is the decay time; α, ω are the attenuation coefficient and angular frequency, respectively.

Therefore, the rock stress field at a distance R from the center of the blast after detonation of a unitary spherical charge charge27 is:

where tR is the time for the stress wave to travel from the unit pack to the observation point.

It can be obtained that the rock stress field at the blasting center distance R after the initiation of the equivalent unit spherical charge of the reduced section charge and the expanded section charge is:

As can be seen from Fig. 1, when the bottom of the detonation, the stress wave at the bottom of the rock is not easy to form a superposition of stress, so the bottom of the rock stress field is mainly determined by the bottom of the charge, combined with the Eq. (9) can be seen, the variable diameter of the decoupled charge at the bottom of the expansion of the radius of the charge can be effectively enhance the bottom of the rock by the stress, and it is mainly by the expansion of the section of the radius of the charge r2 decision.

Assuming that the reduced section of the packet equivalent unit number of spherical packets N, expanding section of the packet equivalent unit number of spherical packets M. Due to the strong superposition of stress in the direction of the blast wave propagation of the explosion. The stress state of the upper rock needs to consider the superposition of all the packets here, the stress field is:

From Eq. (9), Eq. (10) can be seen, the reduced section of the drug charge formed by the weakening of the stress field. But expanding the section of the drug charge to enhance the stress field will be compensated, while the upper body of the rock due to the smaller burden, and by the reflection of the tensile stress, the upper body of the rock fragmentation of the stress required to be easier to meet. The stress field of the upper part of the rock at the same time by the reduced section of the drug charge radius r1, expanding section of the drug charge radius r2 and the reduced section of the drug charge and expanding section of the equivalent unit of spherical drug charge number N and M, them can be determined by the expanding section of the drug charge length H2.

Numerical simulation

Material model and parameters

Material parameters of rock

The RHT constitutive model because of its full consideration of the elastic limit surface, failure surface and damage softening segment equations, etc. on the basis of the model is divided into elasticity, linear reinforcement and damage softening of the three phases28.

In the RHT model, the relationship between strength and strain rate is:

where \(\dot{\varepsilon }_{0}^{{\text{c}}}\) is the reference strain rate for compression. \(\dot{\varepsilon }_{0}^{{\text{t}}}\) is the reference strain rate for tension. P is the pressure. βc and βt are the material constants for compression and tension.

The damage surface is expressed as:

where σf* is the normalized strength. A and N are the damage surface parameters.

In the RHT model, the accumulation of plastic strain εp is used to define the damage value D:

where εpf is the plastic strain at damage.

When a given stress state reaches the ultimate strength of the material at the damage surface, damage accumulates in the form of further inelastic deformation or plastic strain. The plastic strain at damage is:

where εpm is the minimum damage residual strain, Pt* is the pressure at failure, and D1and D2 are damage constants, taken as D1 = 0.04 and D2 = 1.0.

The RHT is widely used in the field of rock explosion impact and other areas of the numerical simulation29,30,31, therefore, the RHT parameters given by the literature32 was selected as the material parameters of the rock in this paper, the specific parameter value in Table 1.

Material parameters of explosive

The explosive material is selected as MAT_HIGH_EXPLOSIVE_MURN and combined with the equation of state JWL_EOS to describe the blasting process of the explosive33, that is:

where V is the volume relative to the undetonated state, E0 is initial specific internal energy, and A, B, R1, R2 and ω are explosive constants.

The parameters used in this paper refer to the existing literature30, and the relevant parameters for the explosives and the equation of state are shown in Table 2.

Material parameters of air

The air material is usually chosen to be described by the MAT_NULL material and the LINEAR_POLYNMIAL equation of state34, which describes the air pressure P as:

where E is the internal energy per volume, μ defines the compression of air by μ = (ρ/ρ0)-1 with ρ and ρ0 being the current and initial density of air, respectively. C0, C1, C2, C3, C4, C5 and C6 are material constants of air, and C4 and C5 can be calculated by C4 = C5 = γ – 1 with γ being the ratio of specific heats.

The air material and equation of state parameters are referred to existing literature35 and are shown in Table 3.

Material parameters of stemming

The stemming material is often chosen to describe the MAT_SOIL_AND_FORM, the parameter values refer to the existing literature36, the specific parameters are shown in Table 4.

Modeling

The overall size of the model is 100 cm × 100 cm × 100 cm. For radial decoupled loading, the size of the borehole and the packet is referred to the common parameters of the actual project. The radius of the borehole is 2.1 cm, the radius of the packet is 1.6 cm, the length of the packet is 60 cm, the length of the gun mud is 20 cm. For the variable diameter decoupled loading, the dimensions of the borehole and the gun mud are kept in the same way as those of the radial decoupled loading, and the size of the packet is only changed. For the convenience of the study, the length of the expanded section is half of the total packet length. Because the actual model size is difficult to achieve the same charging volume of both models, so the radial decoupled charging packet volume as a standard, through the control of the variable diameter decoupled packet volume deviation ΔV to approximate to achieve the purpose of controlling the charging volume unchanged, the specific dimensions of the parameters are shown in Table 5.

The unit system in the model is cm-g-μs, numerical calculations using fluid–solid coupling algorithm, the rock is considered solid, using the Lagrangian grid, the air, explosives, and slurry as a fluid, using Eulerian grid. In this paper, the boundary conditions of the simulation for the tunnel blasting and excavation of the common single free surface situation, that is, the numerical model in addition to the interface belonging to the top of the slurry for the free boundary, the rest of the boundaries for the non-reflective boundaries, the model schematic shown in Fig. 3.

Material parameter and model verification

To verify the material parameters, using the material parameters in Section "Material model and parameters", the mesh size is 1cm, a quasi-two-dimensional model is established for single-hole blasting. The size of the model is shown in Fig. 4(a). The blasting cracks are distributed radially. In this model, the radius of the cracking zone measured is 33.57cm, which is 20.98 times. This result is similar to the conclusion of Siskind and Fumanti37, they concluded that the cracking zone will extend to 20 times the radius of the charge hole.

Then, the sensitivity analysis of mesh size is done. Three mesh sizes are selected in this model, namely, 4 cm, 2 cm, and 1 mm. Figure 4(b) ~ Fig. 4(d) are the blasting cracks with different mesh sizes. The mesh size has a great influence on the blasting crack. When the mesh size is 1 cm, the crack is radioactively distributed, and the radius of the crack zone is ideal. With the increase of the mesh size, the cracks are concentrated near the borehole, and the radius of the fracture zone decreases.

In summary, when the grid size is 1 cm, the rock blasting can be well restored by using the parameters and numerical methods selected in this paper. This verifies the correctness of the parameters and numerical models in this paper. All the models in the following paper will use these parameters and fix the mesh size to 1 cm.

Comparison with radial decoupled charge

In the numerical simulation of rock blasting, the damage distribution is often used to reflect the fragmentation of the rock. The damage characteristics of the two charge structures to the rock are analyzed by extracting the overall damage perspective shown in Fig. 5 in the model.

As shown in Fig. 5, the variable diameter decoupled charge and radial decoupled charge on the rock breakage characteristics have the same consistency. Packet detonation after impacting the wall of the borehole continued to expand the slot cavity, and then from the bottom of the borehole began to produce radial cracks, then the radial cracks continue to develop and begin to appear ring cracks, and finally the radial cracks and ring cracks further development of rock. The rock breaking process is consistent with the current The rock breaking process is consistent with the widely recognized rock breaking theory5,38,39,40.

The variable diameter decoupled charge breaks the rock to a greater extent than the radial decoupled charge. In order to further reflect this difference in the degree of damage, according to the processing flow shown in Fig. 6. First, cut the model into 100 parts in LS-Prepost, and approximately replace the volume within 1 cm of the plane with the area of the plane. Then the cloud image of each plane is imported into Image J to obtain the area of different damage ranges of each plane.

According to the relevant literatur41, the rock mass with the damage value of 0.2 ~ 1.0 is defined as the damaged rock. The damage value of 0.2 ~ 0.9 is further defined as the fractured rock, the damage value of 0.9 ~ 1.0 is the crushed rock. The percentage of damaged, crushed, and fractured rock bodies in each model is calculated, and the obtained data are shown in Fig. 7.

Comparing with radial decoupled loading, the use of variable diameter decoupled loading can break the rock more effectively, in Fig. 7. The rock damage volume increased by 42.24%, and the overall damage percentage reached 37.39%, which is an increase of 11.11% compared with that of 26.28% for radial decoupled loading. Among which the percentage of crushed rock increased by 2.37%, and the percentage of fractured rock increased by 8.73%. In order to further analyze the damage growth at different locations of the rock, the cumulative damage share of the rock and the damage share of each plane are listed, as shown in Fig. 8, 9, 10. The rock is divided into upper and lower parts by taking the place where the diameter of the drug charge changes as the boundary. From Fig. 8, 9, 10, it can be seen that the percentage of damage in the lower part of the rock grows to 7.16%, of which the percentage of crushed rock increases by 1.33%. The percentage of fractured rock increases by 5.83%, the percentage of damage in the upper part of the rock grows to 3.95%, the percentage of crushed rock increases by 1.05%, the percentage of fractured rock increases by 2.9%. Thus, employing the variable diameter decoupled charge results in a more extensive crushing of the lower rock layer, which aligns with the expanding segment of the packet, further enhanced by the expansion section itself. So, the use of variable diameter decoupled loading can not only cause greater crushing of the lower half of the rock corresponding to the expanded section of the drug charge, but also enhance the crushing degree of the upper half of the rock corresponding to the reduced section of the drug charge.

From the above analysis, it can be seen that the variable diameter decoupled charge and radial decoupled charge have the consistency of the breaking characteristics of the rock, and the distribution of the damage produced by the two has similarity. The main difference is that the damage distribution of the range and degree of different, so the damage can be used to characterize the degree of rock fragmentation. It can be obtained that, compared with the radial decoupled charge, the variable diameter decoupled charge produces a greater damage to the rock, rock fragmentation more. The result is that compared with the radial decoupled charge, the variable diameter decoupled charge causes more damage to the rock and more rock fragmentation.

In the numerical simulation analysis of rock blasting, the effective stress (Von Mises stress) is a commonly used analysis index33,42. For this reason, the effective stress data were extracted from 9 measurement points on path I and path II shown in Fig. 11 respectively by a step size of 5 cm, and the data are shown in Fig. 12.

As shown in Fig. 12, the effective stress of the variable diameter decoupled charge is generally greater than that of the radial decoupled charge on Path I and Path II. For Path II, the reason that the variable diameter decoupled charge has greater effective stress is that the diameter of the packet in this section is larger, and the amount of the charge is larger, so a stronger shock wave and compressive stress wave are formed in the part, which is in line with the previous analysis of the stress field of the variable diameter decoupled charge, and the shock wave and the compressive stress wave are the main causes of the blast cavity (crushed area) and the original radial fissure43. For path I, variable diameter decoupled charge here, the diameter of the charge is smaller than the radial decoupled charge, but still has a greater effective stress than the radial decoupled charge. Proving that in the bottom of the detonation conditions, the bottom of the expanding section of the charge of the formation of the superposition of the stress here, to compensate for the upper part of the reduced section of the charge of the weakening of the stress. And even on the upper part of the rock of the stress there is an enhancement of the role, which is in line with the previous analysis of the stress field of the variable diameter decoupled charge. At the same time by the upper rock shown in Fig. 13, a measurement point (15, 0, –25) of the three-way stress state can be seen, variable diameter decoupled charge will increase the upper rock by the tensile stress (tensile stress is positive, compressive stress is negative), and reflective tensile stress will cause the formation of circumferential fracture, while promoting the further extension of radial fracture.

Influence of size parameters on rock breaking effectiveness

Using variable diameter decoupled charging, can crush effectively the rock at the bottom and the whole rock. The reason is changing the distribution of stress field by adjusting the distribution of the charge, so as to adapt it to the resistance of rock crushing. Through Eq. (9) and Eq. (10), the stress field of variable diameter decoupled loading is determined by the radius of the expanding section of the drug charge, the length of the expanding section of the drug charge, and the radius of the shrinking section of the drug charge. Therefore, it is necessary to analyze the effect of these parameters on the crushing of the rock. Because it is difficult to carry out univariate study on it, it is chosen to cross-analyze the influence of these parameters on the rock breaking effect by controlling one variable and the total loading amount, and the specific size of the charges for each working condition is shown in Table 6.

The damage percentage data of each working condition model were obtained according to the method shown in Fig. 6, as shown in Fig. 14, 15, 16.

Figure 14 shows a comparison of the cumulative damage and cross-section damage ratio under the three working conditions with the same length of the expanded section of the drug charge. As can be seen from the figure, the change of the diameter of the packet in the variable diameter decoupled loading structure has a greater effect on the damage degree of the rock. Compared with the working conditions of the expanding section with a packet diameter of 1.70 cm (the diameter of the shrinking section with a packet diameter of 1.49 cm), when the diameter of the expanding section with a packet diameter of 1.72 cm (the diameter of the shrinking section with a packet diameter of 1.47 cm), the degree of damage to the rock was reduced and lower than that of radial decoupled loading, except for a few cases of the expanding section where the diameter of the packet was constant. Coupling charge, except for a few sections, the percentage of damage in all sections have decreased; when the diameter of the expanding section of the drug charge decreased to 1.65 cm (the diameter of the reducing section of the drug charge increased to 1.55 cm), the degree of damage to the rock is only slightly increased, and the percentage of damage between the two in all sections is close to each other, and the difference in cross-section is mainly concentrated in the middle of the rock (in the vicinity of the diameter of the drug charge has been changed). In this group of working condition comparison, when the diameter of the expanded section packet is the largest (the diameter of the reduced section packet is the smallest), the damage is the worst, the proportion of damaged rock is 30.29%; when the diameter of the expanded section packet is the smallest (the diameter of the reduced section packet is the largest), the damage is the best, the proportion of damaged rock is 37.99%. The difference in the proportion of damage between the two is 7.70%. Compared with the optimal working condition, the volume of damaged rock mass in the worst working condition is reduced by 20.26%.

Figure 15 shows a comparison of the cumulative damage and the percentage of cross-section damage under the three conditions of constant diameter of the expanded section charges. As can be seen from the figure, in the case of constant diameter of the expanded section pack, with the decrease of the length of the expanded section pack (accompanied by the increase of the length and diameter of the reduced section pack), the damage degree of the rock decreases. In the comparison of this group of conditions, when the length of the expanding section is the smallest (the length and diameter of the reducing section is the largest), the damage is the worst, the proportion of damaged rock is 32.03%; when the length of the expanding section is the largest (the length and diameter of the reducing section is the smallest), the damage is the best, the proportion of damaged rock is 37.34%. The difference in the proportion of damage between the two is 5.31%. Compared with the optimal working condition, the volume of damaged rock mass in the worst working condition is reduced by 14.22%.

Figure 16 shows a comparison of the cumulative damage and the percentage of cross-section damage under the three working conditions when the diameter of the reduced-section charge is unchanged. As can be seen from the figure, in the case of constant diameter of the reduced section charge, with the increase of the length of the reduced section charge (accompanied by the decrease of the length of the enlarged section charge and the increase of the diameter), the damage degree of the rock decreases. In this group of working condition comparison, when the length of the reduced section charges is the largest (the diameter of the expanded section charges is the largest and the length is the smallest), the damage is the worst, the proportion of damaged rock is 30.18%; when the length of the reduced section charges is the smallest (the diameter of the expanded section charges is the smallest and the length is the largest), the damage is the most optimal, the proportion of damaged rock is 37.99%. The difference in the proportion of damage between the two is 5.96%. Compared with the optimal working condition, the volume of damaged rock mass in the worst working condition is reduced by 20.56%.

The size of each charge has a different degree of impact on the damage of the rock, as can be seen from Table 7, the size of the expanding section of the charge size parameters on the damage of the rock has the greatest impact on the damage of the broken ring. When the expanding section of the charge diameter is larger and the length of the charge is smaller (the greater the length of the reduced section of the charge), which is likely to lead to poorer damage to the rock.

Discussion

In section "Influence of size parameters on rock breaking effectiveness", the size parameters of the variable diameter uncoupled charge are analyzed. However, the change of the size parameters is also accompanied by the change of the cavity shape in the hole. In the uncoupled charge structure, the existence of the cavity in the hole plays a role in balancing the pressure in the hole. In order to understand whether the cavity in the hole has an effect on the damage of rock mass under variable diameter uncoupled charge, a set of test groups was designed, that is, without changing the size of the initial variable diameter uncoupled charge model ( 1.49–30-1.70–30 ), the cavity corresponding to the expansion section of the model was changed to rock mass. At this time, the expanded section of the charge is a coupled charge, and the reduced section of the charge is a decoupled charge. This charge structure is called a locally coupled charge structure.

Figure 17 is the hole wall pressure of three different charge structures ( the hole wall pressure measuring point of the local coupling charge is consistent with the other two charge structures ). It can be seen that the hole wall pressure under the variable diameter uncoupled charge is obviously different from that of the radial uncoupled charge. The peak value of the hole wall pressure formed by the variable diameter uncoupled charge is divided into two obvious sections, which correspond to the expanded section charge and the reduced section charge, respectively. The hole wall pressure of the radial uncoupled charge is more uniform. In addition, in two kinds of variable diameter charge structure, the hole wall pressure of variable diameter charge is greater than that of radial uncoupled charge.

In order to further intuitively reflect the influence of cavity on rock mass damage, the distribution data of blasting damage under variable diameter uncoupled charge and coupled charge are extracted, the results are shown in Fig. 18 and Fig. 19.

As shown in Fig. 18 and Fig. 19, compared with the variable diameter uncoupled charge, the rock mass damage caused by the local coupling charge is smaller, which is reduced by 3.65%. Combined with Fig. 20 and Fig. 21, it can be seen that under the local coupling charge, the energy of the expanded section charge is mostly used to form the crushing zone, resulting in the energy required for rock crushing is much larger than the formation of rock cracks, so that the cracks formed by the rock mass are reduced, and the overall damage degree is reduced.

It can be seen that the cavity has an important effect on the crushing effect of variable diameter decoupled charge, to avoid the formation of localized coupling, combined with Fig. 14 ~ Fig. 16, it can be seen that the smaller the cavity of the expanding section of the drug charge (the larger the radius of the expanding section of the drug charge) tends to lead to poorer rock crushing effect, however, through the comparison of Fig. 7 ~ Fig. 9 and the radial decoupled charge, it can be seen that the larger the cavity of the expanding section of the drug charge (the smaller the radius of the expanding section of the drug charge) does not mean that the rock crushing effect is better. Therefore, the influence of the size parameters (cavity shape) of the variable diameter decoupled charge on the crushing effect of the rock and how to reasonably select the parameters have to be studied in depth.

Conclusions

In this paper, for the single free face under the radial decoupled charge is easy to cause the bottom of the rock crushing insufficient problem, proposed the variable diameter decoupled charge applied to the single free face blasting. The theoretical justification for this method is explored through an analysis of the stress field associated with variable diameter decoupled charges. Additionally, related models for radial decoupled charges, variable diameter decoupled charges, and other parameters are developed using the finite element method, demonstrating the high efficiency of the rock-breaking capabilities of the variable diameter decoupled charge structure. Based on the numerical results and data analysis, several conclusions can be drawn.

By adjusting the loading structure, the variable diameter decoupled loading allows the lower part of the charge to possess a greater loading capacity, thereby enhancing the clamping function of the lower rock. This effectively addresses the issue of insufficient crushing of the rock at the bottom, which is prevalent in radial decoupled loading. Simultaneously, by leveraging the directional effect of stress wave superposition, the method ensures that the stress magnitude on the upper rock is maintained without compromising its crushing effectiveness. Consequently, this approach significantly enhances the overall rock crushing effect. Numerical results indicate that, under the same loading volume, variable diameter decoupled loading increases the rock damage volume by 42.24% and the damage percentage by 11.11% compared to radial decoupled loading. Notably, the damage volume of the lower rock increases by 83.27%, while the damage percentage rises by 7.16%.

In the case of using the same charge without altering the size of the gun hole, the length of the expanded section pack, the radius of the expanded section pack, and the radius of the reduced section pack each exert varying degrees of influence on the rock-breaking efficacy of the variable diameter decoupled charge. Among the 6 conditions evaluated, optimal rock-breaking performance is achieved when the length of the expanded section pack constitutes half of the total length of the pack, and the radius of the expanded section pack is maintained between 1.65 cm and 1.70 cm. Furthermore, the presence of a cavity significantly impacts the rock-breaking effectiveness; when the radius of the expanded section of the charge is larger, it leads to a smaller cavity at the bottom. This diminishes the balancing effect of the cavity on the pressure within the hole, ultimately resulting in reduced damage to the rock.

In this paper, the numerical method is used to verify the rock breaking efficiency of the variable diameter uncoupled charge, and the parameter selection is suggested. However, the specific enhancement of the rock breaking efficiency must be further obtained by field test.

Data availability

Te datasets used during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Zhang, Z. et al. Burden effects on rock fragmentation and damage, and stress wave attenuation in cut blasting of large-diameter long-hole stopes. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 56(12), 8657–8675. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00603-023-03512-y (2023).

Shi, X., Zhang, Z., Qiu, X. & Luo, Z. Experiment study of stemming length and stemming material impact on rock fragmentation and dynamic strain. Sustainability 17(15), 13024. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151713024 (2022).

Zhang, Z. et al. Optimization of the matching relationship between the stemming length and minimum burden in cut blasting of large-diameter long-hole stopes. Geomech. Geophys. Geo-Energy Geo-Res. 9(1), 136. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40948-023-00674-5 (2023).

Ding, C., Yang, R., Zhu, X., Feng, C. & Zhou, J. Rock fracture mechanism of air-deck charge blasting considering the action effect of blasting gas. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 142, 105420. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tust.2023.105420 (2023).

Yang, R. et al. Visualizing the blast-induced stress wave and blasting gas action effects using digital image correlation. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 112, 47–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmms.2018.10.007 (2018).

Cheng, R., Zhou, Z., Chen, W. & Hao, H. Effects of axial air deck on blast-induced ground vibration. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 55, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00603-021-02676-9 (2022).

Yin, Z., Wang, X., Wang, D., Dang, Z. & Bi, J. Analysis and application of stress distribution in 24-m high bench loosening blasting with axially decoupled charge structure in Barun Open-pit Mine. Conf. Ser.: Earth Environ. Sci. 804(2), 022059. https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/804/2/022059 (2021).

Yang, G. L., Yang, R. S., Huo, C. & Che, Y. L. Numerical simulation of air-deck slotted charge blasting. Adv. Mat. Res. 143, 787–791. https://doi.org/10.4028/www.scientific.net/AMR.143-144.787 (2011).

Gao, F. et al. Blasting-induced rock damage control in a soft broken roadway excavation using an air deck at the blasthole bottom. Bull. Eng. Geol. Env. 82(3), 97. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10064-023-03087-6 (2023).

Liu, K. et al. Study on the raising technique using one blast based on the combination of long-hole presplitting and vertical crater retreat multiple-deck shots. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 113, 41–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmms.2018.11.012 (2019).

Jang, H., Handel, D., Ko, Y., Yang, H. & Miedecke, J. Effects of water deck on rock blasting performance. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 112, 77–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmms.2018.09.006 (2018).

Ding, C. et al. Fractal damage and crack propagation in decoupled charge blasting. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 141, 106503. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soildyn.2020.106503 (2021).

Huo, X. et al. Attenuation characteristics of blasting stress under decoupled cylindrical charge. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 56(6), 4185–4209. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00603-023-03286-3 (2023).

Li, X., Liu, K., Sha, Y., Yang, J. & Song, R. Numerical investigation on rock fragmentation under decoupled charge blasting. Comput. Geotech. 157, 105312. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compgeo.2023.105312 (2023).

Wang, Y. et al. Explosion propagation and characteristics of rock damage in decoupled charge blasting based on computed tomography scanning. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 136, 104540. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmms.2020.104540 (2020).

Lou, X., Zhou, P., Yu, J. & Sun, M. Analysis on the impact pressure on blast hole wall with radial air-decked charge based on shock tube theory. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 128, 105905. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soildyn.2019.105905 (2020).

Chen, M., Ye, Z., Lu, W., Wei, D. & Yan, P. An improved method for calculating the peak explosion pressure on the borehole wall in decoupling charge blasting. Int. J. Impact Eng 146, 103695. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijimpeng.2020.103695 (2020).

Yang, R., Ding, C., Yang, L., Lei, Z. & Zheng, C. Study of decoupled charge blasting based on high-speed digital image correlation method. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 83, 51–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tust.2018.09.031 (2019).

Huo, X. et al. Experimental and numerical investigation on the peak value and loading rate of borehole wall pressure in decoupled charge blasting. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 170, 105535. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmms.2023.105535 (2023).

Ding, C. et al. Space-time effect of blasting stress wave and blasting gas on rock fracture based on a cavity charge structure. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 160, 105238. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmms.2022.105238 (2022).

GAO, Q. D. et al. Study on influence law of lnitiation position on transmission of explosion energy and lts comparison and selection in tunnel cutting blasting. China J. Highw. Transp. 35(05), 140–152. https://doi.org/10.19721/j.cnki.1001-7372.2022.05.013 (2022) (in Chinese).

Lou, X. M. et al. Theoretical and numerical research on V-cut parameters and auxiliary cut hole criterion in tunnelling. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/8568153 (2020).

Lou, X., Wang, Z., Chen, B. & Yu, J. Theoretical calculation and experimental analysis on initial shock pressure of borehole wall under axial decoupled charge. Shock. Vib. 2018(1), 7036726. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/7036726 (2018).

Du, J., Luo, Q. & Zong, Q. Analysis on preliminary shock pressure on borehole of airde-coupling charging. J. Xi’an Univ. Sci. Technol. 25(3), 306–310. https://doi.org/10.13800/j.cnki.xakjdxxb.2005.03.009 (2005) (in Chinese).

Liu, K. W. et al. Characteristics and mechanisms of strain waves generated in rock by cylindrical explosive charges. J. Cent. South Univ. 23(11), 2951–2957. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11771-016-3359-7 (2016).

Gao, Q. et al. Regulating effect of detonator location in blast-holes on transmission of explosion energy in rock blasting. Chin. J. Geotech. Eng. 42(11), 2050–2058 (2020) (in Chinese).

Lei, T., Kang, P., Ye, H., Li, N. & Wang, Q. Study on the direction effect of stress wave superposition and fracturedistribution in rock mass during cylindrical charge blasting. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 43(02), 399–411. https://doi.org/10.13722/j.cnki.jrme.2023.0476 (2024).

Wan, A. et al. Analysis of the influence of shear-tensile resistance and rock-breaking effect of cutting holes. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 4917. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-55640-2 (2024).

Li, S. et al. Determination of rock mass parameters for the RHT model based on the Hoek-Brown Criterion. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 56(4), 2861–2877. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00603-022-03189-9 (2023).

Li, X. et al. Numerical study on the behavior of blasting in deep rock masses. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 113, 103968. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tust.2021.103968 (2021).

Pan, C. et al. Numerical investigation of effect of eccentric decoupled charge structure on blasting-induced rock damage. J. Cent. South Univ. 29(2), 663–679. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11771-022-4947-3 (2022).

Li, H. C., Chen, Y., Liu, D. S., Huang, Y. H. & Zhao, L. Sensitivity analysis determination and optimization of rock RHT parameters. Trans. Beijing Inst. Technol. 38(08), 779–785. https://doi.org/10.15918/j.tbit1001-0645.2018.08.002 (2018).

Zhang, Z., Sun, J., Jia, Y., Yao, Y. & Jiang, N. Blasting effects of the borehole considering decoupled eccentric charge. Alex. Eng. J. 88, 116–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aej.2024.01.007 (2024).

Yuan, L. & Yan, C. L. Water-silt composite blasting for tunneling. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 47(6), 1034–1037. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmms.2010.06.004 (2010).

Qiu, X. et al. Effect of borehole deviation on raise formation via long-hole raise blasting. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 154, 106136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tust.2024.106136 (2024).

Cheng, B. et al. Study on the improved method of wedge cutting blasting with center holes detonated subsequently. Energies 15(12), 4282. https://doi.org/10.3390/en15124282 (2022).

Siskind, D.E., Fumanti, R. Blast-Produced Fractures. Lithuania Granite. Report of Investigations 7901 (US Bureau of Mines,1974).

Alan, M. & Peter, M. L. Fragmentation and heave modelling using coupled discrete element gas flow code. Fragblast 1(1), 41–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/13855149709408389 (1997).

Hagan, T. N. Rock breakage by explosives. Acta Astronaut. 6(3–4), 329–340. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-025442-5.50034-2 (1979).

Fakhimi, A. & Lanari, M. DEM-SPH simulation of rock blasting. Comput. Geotech. 55(2), 158–164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compgeo.2013.08.008 (2014).

Liu Xia. Analysis and application of damage analysis of slate tunnel perimeter rock under blasting loads (Guizhou University, 2023).

Liu, X., Tao, T., Tian, X., Lou, Q. & Xie, C. Layout method and numerical simulation study of reduced-hole blasting in large-section tunnels. Front. Earth Sci. 10, 976419. https://doi.org/10.3389/feart.2022.976419 (2022).

Qiu, X. et al. Short-delay blasting with single free surface: Results of experimental tests. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 74, 119–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tust.2018.01.014 (2018).

Funding

National Natural Science Foundation of China, 52064008, Guizhou Provincial High-level Innovative Talents Support Project, Qianke He Platorm Talent-GCC [2022] 004-1, Science and Technology Program of Guizhou Province, Qianke He support [2023] general 120, Guizhou Province Science and Technology Plan Innovative Talents Team Project (Qiankehe Platform Talents-CXTD [2022] 010).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.-B.L.: Theoretical derivation, Writing original draft, The establishment of numerical analysis model. T.-J.T. and C.-J.X.: Editing and checking of manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lyu, J., Tao, T. & Xie, C. Numerical study on the fragmentation of rock under single free face explosion of variable diameter decoupled charge. Sci Rep 15, 11968 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96636-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96636-w