Abstract

Schistosomiasis is a significant public health threat in many regions of Ghana. Due to the abundance of freshwater bodies that serve as a breeding ground for the parasites and their intermediate hosts, the Pru East District is one of the high-risk areas for this disease. This study aims to assess the prevalence of urogenital schistosomiasis and risk factors among school-aged children in the Pru East district of Ghana. A cross-sectional study recruited 452 schoolchildren randomly selected from the Basic Schools in the district between Nov. 2023 and Oct. 2024. A questionnaire was used to obtain demographic, socio-economic, water sources and water collection practices, participants’ knowledge of schistosomiasis, transmission, clinical manifestations, prevention, and control. A urine sample (20 ml) was collected from each participant between 10 am and 1 pm. Samples were transported in a cold chain to the laboratory for assessment. The prevalence of urogenital schistosomiasis was 9.3% and using pipe borne water was associated with 64% reduction (aOR = 0.36, 95%CI = 0.13–0.99, p-value = 0.047). Washing near the river significantly increased the risk of infection, with a 7-fold higher likelihood (aOR = 7.33, 95% CI = 1.59–33.81, p = 0.011). In contrast, individuals who were aware of schistosomiasis had a 98% reduced risk of infection, and those knowledgeable about its transmission had a 96% lower risk compared to their counterparts. None of those recently exposed to praziquantel tested positive. Based on the prevalence of 9.3% obtained, the study area is at a hypo-endemic level for urogenital schistosomiasis. Frequent washing near the river increases infection risk, highlighting the need for behavioral and environmental interventions. People in the study areas should use pipe borne water to reduce infection risk. Understanding schistosomiasis and its transmission lowers the risk of infection, highlighting the importance of health education in raising awareness. Praziquantel is highly effective in both preventing and treating schistosomiasis, reinforcing the need for comprehensive control programs that integrate drug administration, education, and improved water access.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Schistosomiasis, also known as bilharzia, remains a significant public health challenge in many tropical and subtropical regions, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa1. It is caused by parasitic trematodes of the genus Schistosoma, with Schistosoma haematobium and Schistosoma mansoni being the predominant species in Ghana. The disease is transmitted through contact with freshwater contaminated by cercariae released from infected freshwater snails, the intermediate hosts1. Schistosomiasis is associated with chronic morbidity, including anemia, malnutrition, and organ damage, and it disproportionately affects marginalized and rural communities2.

Although six species of Schistosomes have been named, S. haematobium, S. mansoni, and S. intercalatum, have been identified as the primary causative agents of the disease in Africa3. In Ghana, S. haematobium (causing urogenital schistosomiasis) and S. mansoni (causing intestinal schistosomiasis) are the two main parasites responsible for the disease4. A person becomes infected when the free-swimming larvae (cercariae) of the parasite released by certain freshwater snails, infiltrate the skin of individuals who come into contact with water containing the infected snails. Itching and skin rash are signs and symptoms that manifest within a few days of infection. Within 30–60 days of infections, fever, chills, coughs, and muscle aches and pains followed. If untreated, symptoms such as hepatomegaly, haematuria, dysuria, hematochezia, miscarriage, and bladder cancer may develop after years of infection. Although the disease can affect everyone irrespective of their age, it is more prevalent in children below 16 years5.

Though sub-Saharan Africa constitutes only 13% of the world population, it is estimated that more than 80% of the over 230 million schistosomiasis-infected persons worldwide reside in Africa6. The disease remains a major public health threat, especially in tropical and subtropical climates, including Ghana. To control the infection rate, World Vision International introduced the Mass Drug Administration of Praziquantel in Ghanaian basic schools in 2009 as part of an integrated approach to preventing this neglected tropical disease (NTD)7,8. Mass drug administration (MDA) using praziquantel, the primary treatment for schistosomiasis, has been a cornerstone of global efforts to control and eliminate the disease. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends MDA in endemic areas, particularly targeting school-aged children, who are at the highest risk of infection and morbidity1. Praziquantel is highly effective, safe, and cost-efficient, making it the drug of choice for schistosomiasis control programs9.

In Ghana, the national control program for neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) has implemented MDA campaigns for schistosomiasis since the early 2000s. These campaigns aim to reduce infection prevalence, interrupt transmission, and alleviate disease burden10. The implementation process often involves community engagement, health education, and collaboration with schools to ensure widespread coverage and acceptance11. Despite these efforts, challenges such as logistical constraints, variable treatment coverage, and reinfection from untreated water sources persist, particularly in high-endemic districts.

The district under study has been a key focus of Ghana’s schistosomiasis control efforts due to its high prevalence rates linked to extensive water-contact activities, including fishing, washing, and swimming. MDA with praziquantel has been conducted regularly in the district, complemented by efforts to promote behavioral change and improve access to safe water and sanitation. However, limited data exist on the impact and predictors of schistosomiasis infection in this district, highlighting the need for localized evaluations of MDA programs. This study aims to provide critical insights into the effectiveness of praziquantel MDA and associated factors influencing infection rates, contributing to improved control strategies in Ghana.

Despite ongoing intervention strategies, research indicates that the prevalence of Schistosomiasis among schoolchildren in Ghana, especially those residing in farming communities near rivers and dams remains high12. For instance, a study by Abass et al.13. reported that more than 10.4% of residents of riverine communities in the Asuogyaman district of the Eastern region of Ghana were infected13. A similar study by Cunningham et al. (2020) in some selected communities in the Greater Accra region of Ghana reported a prevalence range of 3.3–78%14.

Factors contributing to this sustained prevalence include limited access to clean water, inadequate sanitation facilities, and certain socioeconomic and behavioural factors that increase exposure to infested water bodies15,16. Studies have shown that children engaging in domestic or recreational activities in or near infested water bodies are at a higher risk of contracting the disease17,18. Furthermore, people’s lack of awareness about the disease and its transmission contributes to the difficulty of controlling its spread. Though studies in some of the regions in Ghana have been done, there is a knowledge gap on the prevalence of the disease, its associated risk factors and knowledge of the disease among the school children in the Pru East district. This study aims to assess the prevalence and associated risk factors of Schistosomiasis among selected schoolchildren in the Pru East District. This cohort is particularly vulnerable to this neglected tropical disease.

The study is important because it advances awareness of schistosomiasis, which has an alarming tendency to cause anaemia, stunted growth, and poor cognitive development, all of which influence academic performance and the future potential of schoolchildren.

The findings of this study have the potential to inform targeted interventions, guide policy formulation, and ultimately improve the quality of life of the people in this community, especially the schoolchildren in Ghana. Through this research, we aim to contribute to the global discourse on schistosomiasis, providing valuable insights that can be applied to similar contexts in other parts of Ghana, Africa and worldwide.

Materials and methods

Description of study area

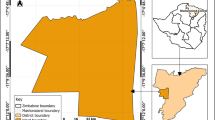

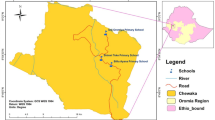

This study was conducted at Yeji, Pru East District. The Pru East district with a capital at Yeji is located at the center of Ghana (coordinates: 8°13´N 0°39´W) (Fig. 1A). The total land mass of the district is 1,178 km². It is geographically located at the basins of Lake Volta and several other tributaries of the Black Volta (Fig. 1B). According to the 2021 population and housing census, the district’s total population is 101,545. The inhabitants therefore depend on these water bodies for farming, fishing, transportation, and domestic and recreational activities, consequently exposing them to numerous water-borne diseases.

The study design

A descriptive cross-sectional study involving 452 participants was conducted between November 2023 and October 2024 in three basic schools randomly selected from the Yeji community.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The study recruited only Basic school children whose guardians and caregivers signed the consent form. Children who refused to participate or whose parents/guardians did not give consent and school girls in their menstrual period were excluded from the study.

Sample size calculation

The sample size for the study was calculated using the equation below19.

Z = 1:96 (95%), p = prevalence of urogenital schistosomiasis = 55% [9], and e = 5% error rate.

A minimum of 380 participants were required for the study but 500 questionnaires were administered to compensate for nonresponse bias.

Survey

A structured close-ended questionnaire was used to collect data about the demographic, socio-economic, water contact and water collection practices. The questionnaire also included the participants’ knowledge of schistosomiasis, its transmission, clinical manifestations, prevention, and control. The questionnaire was prepared in English and then translated into Twi (the native language of the district) for easy understanding by the schoolchildren. The water sources are Pipe-borne water, Pipe and River, River, Sachet water. Clinical manifestations: No knowledge, Dysuria, Hematuria, Itching were responses from the respondents. Urine macroscopy data (Clear, Cloudy, Hematic) was obtained from the urine analysis at the laboratory. Praziquantel: “Have you received praziquantel within 12 months?”

Sample collection

Urine samples were collected from participants in 100 ml sterile and well-labelled screw-capped containers. Approximately 15–20 ml of urine was collected from each participant between 10 am and 1 pm, following the circadian pattern of ova excretion in urine after they were made to perform a quick physical exercise involving jumping and short-distance running to dislodge the ova. Samples were stored on a cold chain (4–6 °C on ice packs) and transported immediately to the laboratory for analysis not more than 2 h after collection to maintain the viability of the eggs.

Laboratory analysis

Urine samples were examined macroscopically and classified into three categories as described by Senghor et al.20. The categories were: clear urine (urine of normal appearance and translucent), cloudy urine (urine of abnormal appearance, not translucent, with suspension elements) and hematic urine (abnormal urine, non-translucent and red). The samples were analyzed for microhematuria using a chemical reagent strip (URIT-10 V urine reagent strips). For each sample, the reagent strip was dipped into the mixed urine, removed and read at the stipulated time by the manufacturer. The change in strip colour was compared to the colour chart on the strips’ container to estimate the amount of blood in the urine. The results of microhematuria were recorded as negative or positive.

For detecting S. haematobium ova (responsible for urogenital schistosomiasis), 10 ml of each urine sample was poured into a 15 ml sterile falcon tube and centrifuged at 2000 rpm for 3–5 min. The supernatants were discarded and the sediments were used to prepare a wet mount on frosted glass slides, stained with iodine and cover-slipped for microscopic examination using the ×10 objective of the Olympus CX23 microscope.

Statistical analysis

We used STATA version 14 software to carry out the statistical. The outcome variable in this study is Schistosomiasis status (takes the values of 1 if Schistosomiasis infection test is positive and 0 if Schistosomiasis infection test is negative). The following variables were considered as potential predictors of Schistosomiasis infection: sex, parent’s occupation (takes the values of 1 for farming and 0 for others (fishing, office work, technical, or trading)), washing near river, source of drinking water, swimming, heard about the disease and knowledge about the disease transmission.

We provide descriptive statistics of the variables used in the data and then estimate prevalence of Schistosomiasis among the study population. We used the chi-square test to investigate the association between the outcome variable (Schistosomiasis status) and predictors of Schistosomiasis infection status. The effectiveness of praziquantel administration in the control of schistosomiasis was investigated using the chi-square test of association. We further quantify the effects of some selected predictors on schistosomiasis infection using logistic regression model21,22,23. Statistical significance was defined as p-value < 0.05.

Results

Sociodemographic data of the study participants

A total of 452 schoolchildren in the Pru-East District were recruited. This included 280 males (61.9%) and 172 females (38.1%). The median age of the participants was 11 years with standard deviation of 3.2 and interquartile range of 5.0–17.0. The parents of the participants were mostly farmers (76.1%), with the remaining involved in office work (8.6%), fishing (5.3%), technical work (4.6%) and trading (5.3%). This is presented in Table 1 below.

Prevalence of schistosomiasis among school children in Pru-East district

The overall prevalence of schistosomiasis among the school children in the Pru-East District was 9.3% (42 out of 452). The infection was higher in males (6.6%) than in females (2.7%). This is presented in Table 2 below.

Logistic Regression Model for the Association Between Risk Factors and Schistosomiasis Infection

Table 3 presents the effects of risk factors on schistosomiasis infection using logistic regression. It includes both unadjusted odds ratios (unaOR) and adjusted odds ratios (aOR), along with their 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) and corresponding p-values.

The results in Table 3 show that male patients had a higher likelihood of schistosomiasis infection (aOR = 1.25, 95% CI = 0.40, 4.00, p = 0.770), though this association was not statistically significant. Washing near the river was significantly linked to a sevenfold increase in infection risk (aOR = 7.33, 95% CI = 1.59, 33.81, p = 0.011), while swimming in water was associated with a twofold increase (aOR = 2.33, 95% CI = 0.66, 8.20, p = 0.188), though the latter was not statistically significant. Individuals aware of schistosomiasis had a 98% lower infection risk (aOR = 0.02, 95% CI = 0.004, 0.06, p < 0.001), and those knowledgeable about its transmission had a 96.5% lower risk (aOR = 0.05, 95% CI = 0.01, 0.22, p < 0.001). Farmers showed a two-fold higher likelihood of infection (aOR = 2.05, 95% CI = 0.44, 9.46, p-value = 0.359), but this was not statistically significant. Lastly, individuals who relied on piped water had a significantly reduced infection risk (aOR = 0.36, 95% CI = 0.13, 0.99, p = 0.047) compared to those using river, sachet, or mixed water sources. Discussion and conclusions are based on only the significant risk factors.

Effectiveness of praziquantel administration among school children

Out of the total number of study participants recruited (n = 452), only 34(7.5%) had taken the Praziquantel (PZQ) as prevention or treatment of previous Schistosomiasis. All 34 were negative for the schistosomiasis infection, while out of the total number of participants who had not taken PZQ before (n = 418), 42(9.3%) were positive for schistosomiasis. However, no statistical association (\(\:{\chi\:}^{2}\) = 3.77, p < 0.052) between those who took PZQ and those who did not (Table 4).

Discussion

Among the 452 school-aged children included in this study, the prevalence of urogenital schistosomiasis was 9.3%. Washing near the river was significantly associated with an increased likelihood of developing the infection. In contrast, individuals who had heard about schistosomiasis exhibited a reduction in the likelihood of infection, while those with knowledge of the disease’s transmission had a lower risk compared to those without such knowledge.

The prevalence of urogenital schistosomiasis observed in this study (9.3%) is slightly lower than the 10.4% reported among school-aged children in the Asuogyaman district of Ghana by Abass et al.13 but significantly higher than the 1.3% prevalence recorded in the Offinso South Municipality of Ghana13, 24. The Offinso South Municipality is less riverine compared to the Asuogyaman district, which contains numerous freshwater bodies. Similarly, the geographic location of Yeji plays a critical role in the transmission dynamics of Schistosoma haematobium. As a town situated near Volta Lake, many local communities depend on the lake and its tributaries for daily activities and recreation, increasing exposure to contaminated water and making the area a high-risk zone for schistosomiasis transmission.

The 9.3% prevalence reported in this study is likely influenced by the presence of freshwater bodies in the Pru East district, which facilitate vector distribution and heighten human-parasite interaction. This finding underscores that schistosomiasis prevalence within the same country can vary significantly between regions due to factors such as population dynamics, environmental and climatic conditions, and local hygienic practices. For instance, a study by Nkya25 reported a 32.5% prevalence of urogenital schistosomiasis in Morogoro Municipality, Tanzania, while Mazigo et al.26 documented prevalences of 0.83% for urogenital schistosomiasis and 21.8% for intestinal schistosomiasis along the Lake Nyasa shoreline in southern Tanzania25,26.

The findings of this study align with existing literature that highlights environmental and behavioral risk factors, as well as the protective role of health education, in schistosomiasis transmission dynamics. The significant association between washing near the river and the increased likelihood of schistosomiasis infection corroborates previous studies emphasizing the role of freshwater contact in the transmission of Schistosoma haematobium. For instance, Grimes et al. (2015) reported that proximity to water bodies and frequent contact with contaminated water are critical risk factors for schistosomiasis, especially in communities reliant on such sources for domestic activities. Similarly, a study in Kenya by Karanja et al. (2002) noted that behavioral practices such as washing, bathing, and swimming in infected water bodies significantly increase infection risks. Several authors27, 28 reported that washing in freshwater bodies as the major risk factor for urogenital Schistosomiasis. The Pru East district is located on the basins of Volta Lake and its several tributaries which remain fresh throughout the year. This provides a suitable ecological niche for breeding the intermediate snail vector. The majority of the people use these freshwater bodies for farming and fishing. Due to the absence of pipe-borne water in most rural communities, the inhabitants depend on these water bodies for domestic activities. Also, schoolchildren use these water bodies for recreational activities such as swimming, games, and fishing. All these activities increase the contact of the inhabitants with the infected water bodies and consequently enhance the contraction of the disease29, 30.

The protective effect of awareness and knowledge about schistosomiasis is also well-documented. In this study, individuals who had heard about schistosomiasis exhibited a 98% reduction in infection likelihood, while those with knowledge of disease transmission had a 96% lower risk of infection. These findings are consistent with research by Chimbari (2012), who demonstrated that health education and community awareness campaigns are effective in reducing schistosomiasis prevalence. These findings are reported in similar studies conducted in Gambia, Niger, Benin, Côte d’Ivoire, and Zimbabwe31,32,33,34,35. Since people’s behaviour is driven by their knowledge levels, those who know about the mode of transmission, symptoms and effects of the disease are more likely to reduce contact with infected water bodies and adopt proper hygienic practices and health-seeking behaviour such as using prescribed prophylaxis or seeking early treatment. Therefore, as part of the strategic intervention, the people of Pru East district should be well-educated about the disease and the need to seek early medical interventions. Also, to encourage proper practices such as water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH), pipe-bone water and toilet facilities should be available to the households as contained in the WHO expert committee report36. Awareness fosters behavioral changes, such as avoiding direct contact with contaminated water and adopting protective practices like wearing shoes and using safe water sources.

Furthermore, the results align with the WHO’s guidelines on schistosomiasis control, which emphasize the integration of health education and behavior change communication as key components in reducing disease transmission37. The significant reduction in infection risk associated with knowledge about disease transmission highlights the importance of incorporating education and awareness programs in endemic areas.

Concerning medication, the study found that mass drug administration of praziquantel which was rolled out in schools in the district has been discontinued since 2011. However, the drug is available at the hospital for the treatment of patients. It was observed that 100% of those who had been recently exposed to the praziquantel either for prophylaxis or treatment exhibited no signs and symptoms of urogenital Schistosomiasis, which underscores the effectiveness of the in controlling the disease. This finding corroborates the reports of studies in Nigeria, South Sudan, Gambia, Burkina Faso, and Ethiopia in which schoolchildren exposed to praziquantel were significantly protected from Schistosomiasis19, 38,39,40,41. Additionally, movements across borders due to wars, famine, drought, and political instability in sub-Saharan Africa also contribute to the sustained rate of infection and reinfection. Therefore, to control the disease in the continent, intervention policies such as mass drug administration, education on proper hygienic practices, and good health-seeking behaviour must be implemented42.

The use of the pipe borne water reduces the risk of Schistosomiasis infection. This finding agrees with studies from various author, who noted that access to safe drinking water plays a crucial role in preventing urogenital schistosomiasis43,44,45. Several authors have demonstrated that individuals who rely on piped water for drinking and household use have a lower risk of infection compared to those using untreated water sources such as rivers, lakes, or open wells43. This reduced risk is primarily due to the fact that Schistosoma larvae (cercariae) require freshwater bodies for their lifecycle, and treated piped water significantly minimizes exposure. Also, a study conducted in rural South Africa demonstrated that high community coverage of piped water decreased a child’s risk of urogenital schistosomiasis infection44. This finding underscores the importance of expanding piped water infrastructure in endemic regions. Other researchers also found that, in rural South Africa, every percentage point increase in piped water coverage was associated with a 4.4% decline in the intensity of re-infection among treated children45.

Conclusion

The prevalence of urogenital schistosomiasis in this study was 9.3%, making the study area a hypo-endemic level for urogenital schistosomiasis. Enhancing access to piped water can significantly reduce both the risk and intensity of urogenital schistosomiasis infections and investments in water infrastructure, alongside other interventions such as health education and mass drug administration, are essential components of comprehensive strategies to control and eventually eliminate this neglected tropical disease. By limiting contact with contaminated water and raising awareness, communities can significantly reduce the burden of schistosomiasis. To further combat the disease, mass drug administration of Praziquantel should be implemented across all basic schools in the Pru East district.

Study limitation

Due to limited time and resources, the study sampled only 452 out of over 3000 schoolchildren in the district. This figure represents a small fraction of the population; therefore, the study could be repeated to cover the entire school-going age children in the district so that those who are infected could be treated. Also, the current study focused on only urogenital schistosomiasis. It would be appropriate for further studies to include intestinal schistosomiasis could also be studied.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

World Health Organization. Schistosomiasis: Progress Report 2001–2021 and Strategic Directions 2022–2030 (WHO, 2022).

Hotez, P. J. et al. The global burden of disease study 2010: interpretation and implications for the neglected tropical diseases. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 8 (7), e2865 (2014).

Barrow, A. et al. Knowledge, attitude, and practice of provincial dwellers on prevention and control of schistosomiasis: evidence from a Community-Based Cross-Sectional study in the Gambia. J. Trop. Med. 2020, 1–9 (2020).

Martel, R. A. et al. Assessment of urogenital schistosomiasis knowledge among primary and junior high school students in the Eastern region of Ghana: A cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 14 (6), e0218080 (2019).

Kokaliaris, C. et al. Effect of preventive chemotherapy with praziquantel on schistosomiasis among school-aged children in sub-Saharan Africa: a Spatiotemporal modelling study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 22 (1), 136–149 (2022).

Aula, O. P., McManus, D. P., Jones, M. K. & Gordon, C. A. Schistosomiasis with a focus on Africa. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 6(3), 109 (2021).

Utroska, J. A. et al. An estimate of global needs for praziquantel within schistosomiasis control programmes / by … et al.] [Internet]. 1990 [cited 2024 Dec 29];PC. Available from: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/61433/WHO_SCHISTO_89.102_Rev1.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

Ouedraogo, H. et al. Schistosomiasis in school-age children in Burkina Faso after a decade of preventive chemotherapy. Bull. World Health Organ. 94 (1), 37–45 (2016).

FENWICK, A. et al. The schistosomiasis control initiative (SCI): rationale, development and implementation from 2002–2008. Parasitology 136 (13), 1719–1730 (2009).

Ghana Health Service. National Neglected Tropical Diseases Programme: Annual report. Accra, Ghana. (2021).

Aryeetey, M. E. et al. Health education and community participation in the control of urinary schistosomiasis in Ghana. East. Afr. Med. J. 76 (6), 324–329 (1999).

World Vision Ghana. Who is World Vision? [Internet]. [cited 2024 Dec 29]; (2024). Available from: https://www.wvi.org/ghana/about-us

Abass, Q., Bedzo, J. Y. & Manortey, S. Impact of mass drug administration on prevalence of schistosomiasis in eight riverine communities in the Asuogyaman district of the Eastern region, Ghana. Int. J. Trop. Dis. Health 41 (15): 18–32 (2020).

Cunningham, L. J. et al. Assessing expanded community wide treatment for schistosomiasis: baseline infection status and self-reported risk factors in three communities from the greater Accra region, Ghana. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 14 (4), e0007973 (2020).

Bronzan, R. N. et al. Impact of community-based integrated mass drug administration on schistosomiasis and soil-transmitted helminth prevalence in Togo. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 12 (8), e0006551 (2018).

Cha, S. et al. Epidemiological findings and policy implications from the nationwide schistosomiasis and intestinal helminthiasis survey in Sudan. Parasit. Vectors. 12 (1), 429 (2019).

Ruberanziza, E. et al. Nationwide remapping of schistosoma mansoni infection in Rwanda using Circulating cathodic antigen rapid test: taking steps toward elimination. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 103 (1), 315–324 (2020).

Deol, A. K. et al. Schistosomiasis — Assessing progress toward the 2020 and 2025 global goals. N. Engl. J. Med. 381 (26), 2519–2528 (2019).

Opara, K. N. et al. Prevalence, risk factors, and coinfection of urogenital schistosomiasis and Soil-Transmitted helminthiasis among primary school children in Biase, Southern Nigeria. J. Parasitol. Res. 2021, 6618394 (2021).

Senghor, B. et al. Prevalence and intensity of urinary schistosomiasis among school children in the district of Niakhar, region of Fatick, Senegal. Parasit. Vectors. 7 (1), 5 (2014).

Iddrisu, A. K. & OAKBFMB, Akooti, J. HIV testing decision and determining factors in Ghana. World J. AIDS. 9 (3), 85–104 (2019).

Iddrisu, A. K., Besing Karadaar, I., Gurah Junior, J., Ansu, B. & Ernest, D. A. Mixed effects logistic regression analysis of blood pressure among Ghanaians and associated risk factors. Sci. Rep. 13 (1), 7728 (2023).

Abdul-Karim, I., Bukari, F. K., Opoku-Ameyaw, K., Afriyie, G. O. & Tawiah, K. Factors That Determine the Likelihood of Giving Birth to the First Child within 10 Months after Marriage. J Pregnancy. ;2020. (2020).

Adu-Gyasi, D., Kye-Amoah, K. & Sorvor, E. Prevalence of urinary schistosomiasis in Offinso-South municipality in Ashanti Region-Ghana. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 14, e270 (2010).

Theresia Estomih Nkya. Prevalence and risk factors associated with Schistosoma haematobiuminfection among school pupils in an area receivingannual mass drug administration with praziquantel: a case study of Morogoro municipality, Tanzania. [cited 2024 Dec 29];Available from: https://www.ajol.info/index.php/thrb/article/view/254671/241800

Mazigo, H. D., Uisso, C., Kazyoba, P., Nshala, A. & Mwingira, U. J. Prevalence, infection intensity and geographical distribution of schistosomiasis among pre-school and school aged children in villages surrounding lake Nyasa, Tanzania. Sci. Rep. 11 (1), 295 (2021).

Mnkugwe, R. H., Minzi, O. S., Kinung’hi, S. M., Kamuhabwa, A. A. & Aklillu, E. Prevalence and correlates of intestinal schistosomiasis infection among school-aged children in North-Western Tanzania. PLoS One. 15 (2), e0228770 (2020).

Mbugi, N. O., Laizer, H., Chacha, M. & Mbega, E. Prevalence of human schistosomiasis in various regions of Tanzania Mainland and Zanzibar: A systematic review and meta-analysis of studies conducted for the past ten years (2013–2023). PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 18 (9), e0012462 (2024).

Bah, Y. M. et al. Schistosomiasis in school age children in Sierra Leone after 6 years of mass drug administration with praziquantel. Front. Public. Health 7, 1 (2019).

Dassah, S. et al. Urogenital schistosomiasis transmission, malaria and anemia among school-age children in Northern Ghana. Heliyon 8 (9), e10440 (2022).

Li, H. M. et al. Schistosomiasis transmission in Zimbabwe: modelling based on machine learning. Infect. Dis. Model. 9 (4), 1081–1094 (2024).

Angora, E. K. et al. Prevalence and risk factors for schistosomiasis among schoolchildren in two settings of Côte D’Ivoire. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 4 (3), 110 (2019).

Onzo-Aboki, A. et al. Human schistosomiasis in Benin: countrywide evidence of schistosoma haematobium predominance. Acta Trop. 191, 185–197 (2019).

Phillips, A. E. et al. Evaluating the impact of biannual school-based and community-wide treatment on urogenital schistosomiasis in Niger. Parasit. Vectors. 13 (1), 557 (2020).

Camara, Y. et al. Mapping survey of schistosomiasis and soil-transmitted helminthiases towards mass drug administration in the Gambia. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 15 (7), e0009462 (2021).

World Health Organization. Prevention and control of schistosomiasis and soil-transmitted helminthiasis: Technical Report Series N°912 [Internet]. [cited 2024 Dec 29]; (2002). Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-TRS-912

World Health Organization. WHO guideline on control and elimination of human schistosomiasis [Internet]. [cited 2024 Dec 29]; (2022). Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240041608

Hajissa, K. et al. Prevalence of schistosomiasis and associated risk factors among school children in Um-Asher area, Khartoum, Sudan. BMC Res. Notes. 11 (1), 779 (2018).

Hussen, S., Assegu, D., Tadesse, B. T. & Shimelis, T. Prevalence of schistosoma mansoni infection in Ethiopia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Trop. Dis. Travel Med. Vaccines. 7 (1), 4 (2021).

Cisse, M. et al. Prevalence and risk factors of schistosoma mansoni infection among preschool-aged children from Panamasso village, Burkina Faso. Parasit. Vectors. 14 (1), 185 (2021).

Joof, E. et al. Prevalence and risk factors of schistosomiasis among primary school children in four selected regions of the Gambia. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 15 (5), e0009380 (2021).

FIFTY-FOURTH WORLD HEALTH ASSEMBLY. Schistosomiasis and soil-transmitted helminth infections [Internet]. 2001 [cited 2024 Dec 29]. Available from: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/78794/ea54r19.pdf

Grimes, J. E. T. et al. The relationship between water, sanitation and schistosomiasis: A systematic review and Meta-analysis. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 8 (12), e3296 (2014).

Mogeni, P., Vandormael, A., Cuadros, D., Appleton, C. & Tanser, F. Impact of community piped water coverage on re-infection with urogenital schistosomiasis in rural South Africa. Elife 9, e54012 (2020).

Tanser, F., Azongo, D. K., Vandormael, A., Bärnighausen, T. & Appleton, C. Impact of the scale-up of piped water on urogenital schistosomiasis infection in rural South Africa. Elife 7, e33065 (2018).

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the entire staff at the Centre of Disease Control and Prevention Unit at the Bono East Regional Assembly, Yeji Government Hospital, and the Pru East District Education Directorate for their support during the data collection.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

George Owusu: Conceptualization; Methodology; Formal analysis; Software; Visualization; Writing—review and editing; Writing—original draft; Supervision; Validation; Data curation; Resources; Investigation; Project administration. Abdul‐Karim Iddrisu: Conceptualization; Investigation; Writing—original draft; Writing— review and editing; Visualization; Validation; Methodology; Data curation; Supervision; Resources; Software; Formal analysis; Project administration. Theophilus Anane Asare: Conceptualization; Investigation; Writing—original draft; Methodology; Visualization; Writing—review and editing; Project administration; Formal analysis; Software; Resources; Data curation; Supervision. Patience Gyekyebea: Data curation; Supervision; Resources; Project administration; Formal analysis; Software; Methodology; Validation; Visualization; Writing—review and editing; Writing—original draft; Conceptualization; Investigation. Raphael Opoku-Kusi: Data curation; Supervision; Resources; Project administration; Formal analysis; Software; Methodology; Validation; Visualization; Writing—review and editing; Writing—original draft; Investigation; Conceptualization. Emmanuel Effah: Data curation; Supervision; Resources; Project administration; Formal analysis; Methodology; Validation; Visualization; Writing—review and editing; Writing—original draft; Investigation; Conceptualization; Software. Ransford Mawuli Tuekpe: Data curation; Resources; Project administration; Formal analysis; Methodology; Validation; Visualization; Writing—review and editing; Writing—original draft; Investigation; Conceptualization; Software; Meshack Antwi-Adjei: Data curation; Supervision; Resources; Project administration; Formal analysis; Methodology; Validation; Visualization; Writing—review and editing; Writing—original draft; Investigation; Conceptualization; Software.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that no conflict of interest exists.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval for this study was obtained from the University of Energy and Natural Resources Committee for Human Research and Ethics (No. CHRE/AP/292/024). A well-written informed consent form was appropriately obtained from each of the participants. The study protocol conformed to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki as reflected in a prior approval by the institution & # 39; human research committee.

Transparency statement

The lead author George Owusu affirms that this manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned (and, if relevant, registered) have been explained.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Owusu, G., Iddrisu, AK., Antwi-Adjei, M. et al. Assessment of the prevalence and praziquantel effectiveness and risk factors of urogenital schistosomiasis among school-aged children in pru east, Ghana. Sci Rep 15, 19376 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96653-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96653-9

) within the Bono East district.

) within the Bono East district.