Abstract

Prostate cancer remains a significant health concern due to its high mortality rate, emphasizing the need for innovative therapeutic approaches. This study aims to explore the potential anticancer effects of a drug nanocomplex containing rosmarinic acid in the treatment of prostate cancer, aiming to contribute to the development of safer and more effective treatment options for cancer patients. Nanocomposite Graphene Oxide was synthesized following the Hummers’ method. The resulted product dissolved in deionized water with rosmarinic acid to prepare the final product. To investigate the effects of rosmarinic acid@Se-TiO2-GO, PC3, LNCaP, and normal (HFF-1) cell lines were treated with varying concentrations (7.8, 15.6, 31.2, 62.5, 125, 250, and 500 µg/ml) of the nanocomplex. Cell viability was assessed using the Resazurin test, while levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS), gene expression (Bcl-2 and Bax), and total antioxidant capacity were measured in both cancerous and normal cells. The Se-TiO2-GO nanoparticles demonstrated high entrapment efficiency and loading capacity for rosmarinic acid. The IC50 values after 24 and 48 h of RA treatment were significantly greater than those recorded for treatments involving rosmarinic acid@Se-TiO2-GO. Treatment with rosmarinic acid@Se-TiO2-GO resulted in decreased cell viability and increased apoptosis in PC3 and LNCaP cells, while showing no inhibitory effects on the normal cell line (HFF-1) at concentrations toxic to cancer cells. Additionally, a dose-dependent increase in ROS levels, a decrease in total antioxidant capacity, elevated Bax gene expression, and reduced Bcl-2 expression were observed in the cancer cells following treatment with the nanocomplex. The cytotoxic effects of rosmarinic acid@Se-TiO2-GO nanoparticles on prostate cancer cells appear to be mediated through the generation of oxidative stress and induction of apoptosis. The unique formulation of these nanoparticles holds promise for future prostate cancer treatment strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cancer, a formidable disease characterized by an imbalance between cell proliferation and apoptosis, remains a major global health challenge. Traditional treatment methods, including surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy, often fall short in terms of efficacy and can lead to adverse side effects on healthy tissues1. Prostate cancer, in particular, ranks as the second most common cancer among men worldwide2,3, underscoring the urgent need for innovative treatment strategies that enhance therapeutic effectiveness while minimizing harm to healthy cells4. Nanotechnology has gained attention as a promising approach to overcoming the limitations of conventional treatments. Nanostructured systems offer unique advantages such as high precision, low invasiveness, and reduced side effects, making them ideal candidates for enhancing cancer therapies5,6. Concurrently, there is a growing interest in utilizing natural products and compounds derived from plants as potential anticancer agents. Herbal products, due to their bioactive compounds, have shown promise in cancer prevention and treatment, providing an effective and often less toxic alternative to synthetic drugs7,8.

Rosmarinic acid (RA) is a particularly noteworthy natural compound. This phenolic ester, found abundantly in herbs such as spearmint, has been traditionally used in various medicinal practices. RA is renowned for its diverse biological properties, including anti-inflammatory, antidiabetic, and anticancer activities9,10. Recent research has underscored its potential to inhibit metastasis, particularly bone metastasis in breast cancer models11,12. Despite its promising properties, RA’s clinical application is limited due to its rapid metabolism and low bioavailability, necessitating the development of advanced delivery systems to enhance its therapeutic efficacy. Nanotechnology offers a solution to these limitations by providing effective delivery mechanisms for RA13,14.

Titanium dioxide (TiO2) nanoparticles, known for their high biocompatibility, controlled release capabilities, and low toxicity, are especially promising. TiO2 nanostructures have demonstrated the potential to significantly improve drug uptake, extend drug release times, and enhance treatment outcomes15,16. Numerous studies have demonstrated that drug delivery systems employing TiO2-based nanostructures can significantly improve treatment outcomes17.

For instance, studies have shown that conjugation of drugs like doxorubicin to TiO2 nanoparticles and loading of chemotherapeutics on TiO2-based systems can lead to higher drug accumulation and improved cancer cell targeting18. Similarly, the conjugation of doxorubicin to TiO2 nanoparticles has shown a synergistic response in breast cancer cell lines, while cisplatin loaded on hyaluronic acid-TiO2 nanoparticles resulted in increased drug accumulation compared to free cisplatin19.

Selenium (Se), another compound with substantial anticancer properties, adds further value to this approach. Selenium acts through mechanisms such as modulating redox-active proteins, regulating immune responses, inducing apoptosis, and inhibiting cancer cell invasion and angiogenesis. Its combination with other anticancer agents can synergize to boost efficacy while maintaining low toxicity20,21,22. However, for optimal use in a drug delivery system, a suitable carrier substrate is necessary.

Graphene oxide (GO) serves as an excellent carrier due to its unique properties, including a high surface area and the presence of oxygen-containing functional groups that enable efficient drug binding. GO is known for its biocompatibility, low toxicity, and ability to facilitate interactions like adsorption, π–π bonding, and hydrogen bonding. These properties make GO ideal for loading and distributing compounds such as TiO2 and selenium, enhancing drug stability and controlled release23.

By leveraging the combined properties of RA, TiO2, and selenium, we aim to create a system that maximizes anticancer efficacy while minimizing side effects. The integration of these components into a GO-based nanocarrier seeks to optimize the delivery and therapeutic impact of RA in PC3 and LNCaP prostate cancer cells. In conclusion, this study proposes an innovative approach that harnesses the synergistic effects of RA, TiO2, and selenium to advance prostate cancer treatment. The use of GO as a substrate ensures efficient delivery and controlled release, paving the way for enhanced therapeutic outcomes and a reduction in adverse effects. This research holds promise for developing new, effective strategies in cancer nanomedicine.

Materials and methods

Chemicals and reagents

The main materials used for the experiments included graphite powder, sodium selenite (Na2SeO3), and 4-dimethylaminopyridine (DMAP) sourced from Sigma Aldrich. Rosmarinic acid was obtained from Carbosyn (FR02310). Additional chemicals such as titanium dioxide, hydrogen peroxide (30% H2O2), sulfuric acid (H2SO4), potassium permanganate (KMnO4), sodium nitrate (NaNO3), ascorbic acid, and acetic acid were purchased from Merck. The reagent 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl) carbodiimide hydrochloride (EDC) was supplied by Fluka. All experiments were conducted using deionized water.

Synthesis of Se-TiO2-GO

Nanocomposite Graphene oxide (GO) was synthesized from graphite powder following the Hummers’ method as outlined in previous studies24,25,26. For the Se-TiO2-GO composite, 20 mg of GO was initially dispersed in water and sonicated to ensure homogeneity. Next, 15 mg of sodium selenite was added, along with 10 ml of ascorbic acid, and the mixture was stirred for 30 min. Subsequently, 8 mg of TiO2, also dispersed in water, incorporated into the mixture. The resulting mixture was stirred for 24 h. After the synthesis was complete, the mixture was washed with deionized water and centrifuged using a Tomy centrifuge (Japan) at 12,000 g for 15 min. The precipitate was collected and freeze-dried for further use.

Preparation of Rosmarinic acid@ Se-TiO2-GO

For rosmarinic acid encapsulation, 15 mg of Se-TiO2-GO was dissolved in deionized water, followed by the addition of 20 mg of rosmarinic acid dissolved in 1 mL of DMSO/water. This mixture was stirred at room temperature for 24 h, centrifuged at 7000 rpm for 15 min, and the supernatant was used to measure unbound rosmarinic acid. The precipitate was washed with deionized water, freeze-dried, and stored at 4 °C for later analysis.

Characterization and encapsulation efficiency

The size, PDI, and zeta potential of the Se-TiO2-GO and rosmarinic acid@Se-TiO2-GO composites were measured using dynamic light scattering (DLS) (Malvern Zetasizer Nano ZS). Surface morphology and structure were analyzed via field emission scanning electron microscopy (FE-SEM) using the Mira III FEG. FTIR spectra of the samples were obtained using a Perkin Elmer Paragon 1000 FTIR spectrometer with KBr pellets. Encapsulation efficiency and drug loading capacity were determined by centrifuging the rosmarinic acid@Se-TiO2-GO solution and analyzing the supernatant at 330 nm using a Cecil CE 2501 UV-visible spectrophotometer27.

The loading capacity and encapsulation efficiency were calculated as:

Cell line and culture conditions

This study was conducted at Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Iran. Prostate cancer cell lines (PC3, LNCaP) and HFF-1 human fibroblast cells were obtained from the Pasteur Institute of Iran. PC3 and LNCaP cells were cultured in RPMI 1640, while HFF-1 cells were grown in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM), both media containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin. The cells were maintained at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 humidified incubator.

Cytotoxicity assay (resazurin test) of the rosmarinic acid, Se-TiO2-GO and rosmarinic acid@Se-TiO2-GO

The Resazurin cell viability assay assesses the ability of metabolically active cells to convert non-fluorescent resazurin into fluorescent resorufin and dihydro-resorufin. This reduction process correlates directly with the number of viable cells present in the sample. In brief, PC3 and LNCaP cells were plated in 96-well plates at a density of 1 × 104 cells per well and incubated for 24 h. The cells were then treated with various concentrations of rosmarinic acid, Se-TiO2-GO, and rosmarinic acid@Se-TiO2-GO (ranging from 7.8 to 500 µg/mL) for durations of 24–48 h. After treatment, the medium was discarded, and 10 µL of resazurin solution (0.01 mg/mL, prepared in phosphate-buffered saline from Sigma-Aldrich) was added to each well. The plates were incubated for 3 h at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere and kept away from light. Colorimetric measurements were taken using a microplate fluorimeter, targeting excitation and emission wavelengths of 600 nm and 570 nm, respectively. The results were expressed as percentage survival rates by comparing the absorbance of treated cells to that of untreated controls, and the IC50 values were calculated using GraphPad Prism software (version 6.0).

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) measurement

The intracellular ROS levels were measured using the 2,7-dichlorodihydro fluorescein diacetate (DCFDA, Sigma, USA) technique. PC3 and LNCaP cells were incubated for 24 h, followed by incubation with 20 µM DCFDA for 30 min. The cells were then exposed to different concentrations of rosmarinic acid@Se-TiO2-GO. Tert-butyl hydro peroxide (TBHP) was used as a positive control. Fluorescence was measured at 490/530 nm (excitation/emission) with a PerkinElmer spectrophotometer.

Total antioxidant capacity (TAC) analysis

Total antioxidant capacity (TAC) was assessed using a commercial assay kit (Teb Pazhouhan Razi, Tehran, Iran). Our cell lines were treated with rosmarinic acid@Se-TiO2-GO at concentrations of 10, 15, and 30 µg/ml. After treatment, the cells were lysed using a freeze-thaw method, and the lysate was centrifuged at 12,000g for 15 min using Tomy centrifuge (Japan) to collect the supernatant. We then added the necessary reagents to the supernatant, adhering to the manufacturer’s guidelines. Finally, TAC levels were determined by measuring the absorbance of the samples against a standard curve.

Gene expression analysis using quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR)

RNA was isolated from PC3 and LNCaP cells treated with rosmarinic acid@Se-TiO2-GO at concentrations of 10–30 mg/mL using the RNA extraction kit provided by Pars Tous Biotechnology (Iran), following the manufacturer’s instructions. After assessing the purity, concentration, and integrity of the extracted RNA with the Thermo Scientific NanoDrop™ Lite, 1 µg of RNA was converted to complementary DNA (cDNA) using a cDNA synthesis kit.

Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) was conducted using the LightCycler® 96 RT-PCR system from Roche (USA), employing SYBR Green as the fluorescent dye. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) served as the internal control. The analysis of relative gene expression changes was performed using the ΔΔCT method with GraphPad Prism software (version 6.0). The primers for qRT-PCR, targeting Bcl-2 and Bax, were sourced from Pishgaman Co. (Tehran, Iran).

In this study, our research team designed and carefully selected primers to specifically target the genes we were interested in. To make sure these primers worked effectively and accurately, we used a serial dilution method to create a standard curve and check how well they amplified the target genes.

Statistical analysis

All experiments were analyzed using GraphPad Prism v6, expressed as mean ± SEM. One-way ANOVA was used for comparisons, and statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

Physicochemical characteristics of Se-TiO2-GO

Zeta potential, DLS and PDI

The particle size, polydispersity index (PDI), and zeta potential of the Se-TiO2-GO and rosmarinic acid@Se-TiO2-GO formulations are summarized in Table 1. The mean particle size of the Se-TiO2-GO and rosmarinic acid@Se-TiO2-GO was found to be 314.2 nm and 344.8 nm, with PDI 0.253 and 0.333 respectively. Additionally, the zeta potential measurements revealed positive values for Se-TiO2-GO and negative values for rosmarinic acid@Se-TiO2-GO.

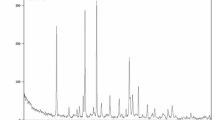

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR)

In Fig. 1, distinctive absorbance peaks at 1695 cm− 1 and 3413 cm− 1 are observed, corresponding to the stretching vibrations of the carboxyl (C=O) and hydroxyl (-OH) groups present in graphene oxide and rosmarinic acid, respectively23,28. The peaks in rosmarinic acid@Se-TiO2-GO are broader than those in Se-TiO2-GO, likely due to the incorporation of hydroxyl and carboxyl groups from rosmarinic acid into the spectrum.

Additionally, the absorbance peak at 1388 cm− 1 indicates the presence of carbonyl groups in GO23. The peak in the 1400–1350 cm− 1 range is attributed to C-O-C stretching in rosmarinic acid28. The FT-IR spectrum of the two nanocomposites also shows the presence of TiO2, as evidenced by a broad band observed at 1006 cm− 1, which is assigned to the Ti-O bond of TiO2. The appearance of an absorption peak at 476 cm− 1 indicates the presence of Se-O, consistent with previous research findings29.

Surface morphology and elemental composition (FESEM and EDX)

FESEM images (Fig. 2A,B) provided insights into the morphology and structure of Se-TiO2-GO and rosmarinic acid@Se-TiO2-GO. Nanoparticles of Se-TiO2-GO were distributed across the GO sheets, presenting varied shapes within the nanoscale range. The addition of rosmarinic acid led to distinct formations that covered much of the GO surface. Elemental mapping from EDX analysis (Fig. 2C) confirmed the presence of carbon (C) and oxygen (O) from GO and rosmarinic acid, as well as selenium (Se) and titanium (Ti), indicating successful nanocomposite synthesis.

Drug entrapment and loading efficiency

The rosmarinic acid content within the synthesized nanoparticles was measured to evaluate loading and entrapment efficiency. After synthesis, the nanocomposites were centrifuged, and free rosmarinic acid in the supernatant was quantified via UV-visible spectrophotometry. The Se-TiO2-GO formulation exhibited an entrapment efficiency of 68.7% and a loading capacity of 43.2%.

Effect of rosmarinic acid and rosmarinic acid@Se-TiO2-GO on cell viability of PC3 and LNCaP cell lines.

The effects of both rosmarinic acid and rosmarinic acid@Se-TiO2-GO were tested on PC3, LNCaP, and HFF-1 cell lines using increasing concentrations (7.8 to 500 µg/ml) over 24 and 48-hour periods. Results indicated that the IC50 for PC3 cells treated with rosmarinic acid was 85 µg/ml at 24 h and 59 µg/ml at 48 h (Fig. 3A). LNCaP cells showed IC50 values of 102 µg/ml and 64 µg/ml at 24 and 48 h, respectively (Fig. 3B). The treatment with rosmarinic acid@Se-TiO2-GO resulted in lower IC50 values for both cell lines, at 43 µg/ml and 22 µg/ml for PC3 (Fig. 3C), and 56 µg/ml and 29 µg/ml for LNCaP (Fig. 3D).

The HFF-1 cell line had IC50 values of 186 µg/ml and 140 µg/ml at 24 and 48 h, respectively, after exposure to rosmarinic acid@Se-TiO2-GO (Fig. 4).

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) production in cancer cells

ROS levels in PC3 and LNCaP cells were measured following treatment with rosmarinic acid@Se-TiO2-GO at concentrations of 10, 15, and 30 µg/ml (Fig. 5A, B). Data indicated a significant dose-dependent increase in ROS levels at 15 and 30 µg/ml, suggesting that the treatment enhanced oxidative stress in cancer cells compared to untreated controls.

Effect of Rosmarinic acid@Se-TiO2-GO on the total antioxidant capacity (TAC)

The influence of rosmarinic acid@Se-TiO2-GO on TAC in cancer cell lines was evaluated (Fig. 6A, B). The LNCaP cell line showed a marked reduction in TAC at a concentration of 30 µg/ml, whereas the PC3 cell line exhibited significant TAC decreases at both 15 and 30 µg/ml, implying enhanced oxidative stress.

Gene expression analysis of Bax and Bcl-2

The impact of rosmarinic acid@Se-TiO2-GO on pro-apoptotic (Bax) and anti-apoptotic (Bcl-2) gene expression in PC3 and LNCaP cell lines was analyzed (Fig. 7A–D). Treatment with 15 and 30 µg/ml of the nanoparticle led to a significant increase in Bax expression and a concurrent decrease in Bcl-2 expression in both cell lines, indicating induced apoptosis compared to the untreated control groups.

Discussion

Prostate cancer is the most prevalent malignancy among men and is recognized as the second primary cause of cancer-related deaths among the male worldwide30. Prostate cells can be categorized into two subtypes: AR+ (hormone-sensitive) and AR− (hormone-refractory). LNCaP cells are a representative example of the AR + subtype, whereas PC-3 cells are classified as AR-. As a result, we explored both cell lines in this research31. Despite existing research that highlights the chemopreventive capabilities of rosmarinic acid (RA) in combating various forms of cancer, the exact mechanisms driving its effectiveness remain not fully elucidated. Conventional chemotherapy, designed to target rapidly dividing cells, frequently lacks specificity, thereby impacting healthy cells as well as cancerous ones32,33. This underlines the critical need for innovative chemotherapy agents that possess reduced toxicity levels. Challenges such as RA’s poor solubility, limited bioavailability, and instability have necessitated the exploration of alternative delivery methods32,34. One of the promising advancements is utilizing nanoparticles to optimize RA’s bioavailability and therapeutic potential. In this study, we pioneered the creation of a novel nanocomposite, rosmarinic acid@Se-TiO2-GO, which marks the first exploration of this RA formulation’s effectiveness in treating prostate cancer.

Our research involved testing the effects of both rosmarinic acid@Se-TiO2-GO and RA alone on PC3 and LNCaP prostate cancer cell lines, along with HFF-1, a normal cell line. We observed that the IC50 values after 24 and 48 h of RA treatment were nearly double those recorded for treatments involving rosmarinic acid@Se-TiO2-GO, indicating greater potency for the nano formulation. Importantly, the IC50 levels for the HFF-1 cells suggested that at the therapeutic doses intended for cancer cells, the nanoparticle formulation did not adversely affect normal cells, highlighting its safety and efficacy.

According to our research, the IC50 for PC3 cells treated with rosmarinic acid was 85 µg/ml at 24 h and 59 µg/ml at 48 h. Our findings align with previous studies, such as research involving Ls174-T colorectal cancer cells, which demonstrated that RA preserved over 70% cell viability and reduced metastasis without notable cytotoxicity34,35. Jaglanian et al. also found a dose-responsive decline in proliferation for both androgen-independent PC-3 and androgen-dependent 22RV1 prostate cancer cells when treated with RA36. Similarly, studies show that RA decreases cell viability in 22RV1 and LNCaP prostate cancer lines by modulating CHOP/GADD153, promoting androgen receptor degradation, and reducing xenograft tumor growth37. Moreover, rosmarinic acid has been shown to induce a dose-dependent decrease in the proliferation and viability of PC-3, DU145, and LNCaP prostate cancer cells36.

According to a study by Liu in 2024, rosmarinic acid specifically inhibits the non-inflammatory effects of COX-2. The researchers applied rosmarinic acid in combination with ginsenoside Rg1 to colon cancer cells. In this study, metastasis of the cancer was inhibited by the COX-2-MYO10 axis in both in vivo and in vitro models38.

Zeta potential measurements of our formulation revealed distinct properties: Se-TiO2-GO showed a positive zeta potential, while rosmarinic acid@Se-TiO2-GO had negative values, which may affect stability, dispersibility, and cellular interactions.

Electrostatic forces are essential for the uptake of these charged nanoparticles, as the adsorption of proteins onto the surface can alter their physical and chemical behavior, impacting cellular absorption and overall efficacy.

Characterization through FT-IR spectroscopy confirmed the attachment of RA to the nanocomposite, shown by increased O-H peak intensities indicative of hydroxyl groups from RA. FESEM and EDX analyses supported this, revealing structural changes on the graphene oxide surface due to π-π stacking and electrostatic interactions that facilitate drug delivery. EDX data confirmed the inclusion of selenium and titanium, validating the successful conjugation of the nanoparticle components.

Cancer tissues often have elevated reactive oxygen species (ROS)33,39, which contribute to genetic instability, enhanced proliferation, and drug resistance40,41. Xu et al. explored RA’s anti-metastatic functions, demonstrating its ability to inhibit cell migration, adhesion, and invasion in a dose-dependent manner while reducing ROS levels by enhancing the levels of reduced glutathione42. Rosmarinic acid also suppressed the activity of matrix metalloproteinase-2 and -9, effectively inhibiting tumor metastasis both in vitro and in vivo43.

Rosmarinic acid’s unique characteristics as both a phenolic acid and a flavonoid-related compound enable it to bind metal ions. This binding inhibits the formation of free radicals and effectively halts oxidative chain reactions. Furthermore, rosmarinic acid can influence the activity of key enzymes associated with oxidative stress, such as superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT), and glutathione peroxidase (GPx)44.

Our study showed a dose-dependent ROS increase in PC3 and LNCaP cells treated with the nano formulation, suggesting that these raised levels trigger oxidative stress, leading to apoptosis.

In normal, healthy cells, there is a balance between ROS production and antioxidant defenses45. To provide more reliable evidence, we also examined the total antioxidant capacity (TAC) of the prostate cancer cell lines. Following treatment with 30 µg/mL of the nano complex, there was a significant decrease in TAC, which correlated with increased ROS production in the cancer cells. Notably, even 15 µg/mL of the nano complex significantly reduced the antioxidant capacity in the PC3 cell line compared to LNCaP, which may reflect inherent differences between these two cell lines.

Additionally, earlier work, such as Yang et al.‘s research on metastatic colorectal cancer, indicated that RA can heighten ROS production and suppress epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) via p38/AP-1 pathways, with miR-1225-5p mediating its anti-metastatic effects46. RA has also been highlighted for its protective and anticancer properties in various studies, emphasizing its utility across different cancer types. For instance, Ngo et al. reviewed RA’s protective effects against prostate, colorectal, and other cancers, highlighting its dose-dependent anticancer potential across various stages of cancer development47. Moreover, Areti et al. found that rosmarinic acid prevented functional deficits, reduced oxidative stress, and improved mitochondrial function in a rat model of oxaliplatin-induced peripheral neuropathy48.

Apoptosis, disrupted in many cancer types, can occur via intrinsic and extrinsic pathways4. The impact of rosmarinic acid on prostate cancer cell apoptosis was analyzed, showing that rosmarinic acid down regulated procaspase-9, Bcl-xL, and Bcl-2, thereby inducing apoptosis through both apoptotic pathways49,50. In our in vitro study, rosmarinic acid@Se-TiO2-GO significantly reduced the viability of cancer cells. The nanoparticles likely exerted cytotoxic effects by elevating ROS levels, decreasing total antioxidant capacity, increasing Bax (pro-apoptotic) gene expression, and reducing Bcl-2 (anti-apoptotic) expression, as confirmed by real-time PCR. These findings are consistent Jang et al. (2018) study, which investigated the pro-apoptotic effects of rosmarinic acid in human prostate cancer cell lines. They demonstrated that rosmarinic acid induces apoptosis by modulating HDAC2 expression. Their study revealed that rosmarinic acid affects the expression of key proteins involved in the intrinsic mitochondrial apoptotic pathway, including Bax, Bcl-2, caspase-3, and cleaved poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 (PARP-1), through the up regulation of p53 as a result of HDAC2 down regulation. This led to increased apoptosis in PC-3 and DU145 cells, suggesting that rosmarinic acid not only inhibits cell survival but also promotes apoptosis in prostate cancer cell lines, positioning rosmarinic acid as a potential novel therapeutic agent .

This study is the first to specifically investigate how rosmarinic acid, in combination with titanium oxide and selenium-doped graphene oxide, affects prostate cancer cells like PC3 and LNCaP. We successfully highlighted the roles of Bax and Bcl-2 in this process. However, while rosmarinic acid is known to interact with multiple signaling pathways, the exact mechanisms involved remain unclear. Additionally, further research is needed, both in vivo and in vitro, to fully uncover the anticancer potential of this combination and its applicability in real-world treatments.

Conclusion

This study successfully synthesized rosmarinic acid@Se-TiO2-GO nanoparticles, demonstrating that their optimized average size and negative surface charge improved both bioavailability and biodistribution, facilitating targeted delivery to cancer cells. When PC3 and LNCaP prostate cancer cell lines were treated with these nanoparticles at varying concentrations, results showed a dose-dependent increase in reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, a decrease in total antioxidant capacity, upregulation of Bax gene expression, and downregulation of Bcl-2 expression. These observations imply that the nanoparticles exert their antitumor effects primarily through the induction of ROS. Collectively, the findings suggest that rosmarinic acid@Se-TiO2-GO nanoparticles could be a promising addition to future treatment protocols for prostate cancer. Nonetheless, further investigation is essential to comprehensively determine their mechanism of action and overall therapeutic efficacy in prostate cancer.

Data availability

The authors of this article will share all the data underlying the findings of their manuscripts with other researchers. Therefore, I hereby declare the statement of “availability” for the data used in this manuscript. Researchers can communicate with the corresponding authors for the data by email.

References

Khoshghamat, N. et al. Programmed cell death 1 as prognostic marker and therapeutic target in upper Gastrointestinal cancers. Pathol. - Res. Pract. 220, 153390 (2021).

Rawla, P. Epidemiology of prostate cancer. World J. Oncol. 10 (2), 63 (2019).

Akbari, S. et al. The anti-tumoral role of hesperidin and aprepitant on prostate cancer cells through redox modifications. Naunyn. Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 396 (12), 3559–3567 (2023).

Jafarinezhad, S. et al. The SP/NK1R system promotes the proliferation of breast cancer cells through NF-κB-mediated inflammatory responses. Cell. Biochem. Biophys. 81 (4), 787–794 (2023).

Einafshar, E. & Ghorbani, A. Advances in black phosphorus quantum Dots for cancer research: synthesis, characterization, and applications. Top. Curr. Chem. 382 (3), 25 (2024).

Einafshar, E., Einafshar, N. & Khazaei, M. Recent advances in MXene quantum Dots: A platform with unique properties for General-Purpose functional materials with novel biomedical applications. Top. Curr. Chem. 381 (5), 27 (2023).

Mayzlish-Gati, E. et al. Review on anti-cancer activity in wild plants of the middle East. Curr. Med. Chem. 25 (36), 4656–4670 (2018).

Mozafari, M. et al. Potential in vitro therapeutic effects of targeting SP/NK1R system in cervical cancer. Mol. Biol. Rep. 49 (2), 1067–1076 (2022).

Chen, Y. et al. Variation in concentrations of major bioactive compounds in prunella vulgaris L. related to plant parts and phenological stages. Biol. Res. 45 (2), 171–175 (2012).

Mehrabi, M. et al. Development of a human epidermal growth factor derivative with EGFR-blocking and depleted biological activities: A comparative in vitro study using EGFR-positive breast cancer cells. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 103, 275–285 (2017).

Xu, Y. et al. Inhibition of bone metastasis from breast carcinoma by Rosmarinic acid. Planta Med. 76 (10), 956–962 (2010).

Amoah, S. K. et al. Rosmarinic acid–pharmaceutical and clinical aspects. Planta Med. 82 (05), 388–406 (2016).

Hashemzadeh, H., Javadi, H. & Darvishi, M. Study of structural stability and formation mechanisms in DSPC and DPSM liposomes: A coarse-grained molecular dynamics simulation. Sci. Rep. 10 (1), 1837 (2020).

Einafshar, E. et al. Temozolomide and Doxorubicin Combined Treatment by Graphene Oxide-Cyclodextrin Nanocarriers for Synergistic Inhibition of Glioblastoma Cells. BioNanoScience (2024).

Çeşmeli, S., Biray, C. & Avci Application of titanium dioxide (TiO(2)) nanoparticles in cancer therapies. J. Drug Target. 27 (7), 762–766 (2019).

Zhen, S. et al. Comparison of serum human epididymis protein 4 and carbohydrate antigen 125 as markers in ovarian cancer: A meta-analysis. Mol. Clin. Oncol. 2 (4), 559–566 (2014).

Jafari, S. et al. Biomedical applications of TiO2 nanostructures: recent advances. Int. J. Nanomed. 3447–3470. (2020).

Akram, M. W. et al. Tailoring of Au-TiO2 nanoparticles conjugated with doxorubicin for their synergistic response and photodynamic therapy applications. J. Photochem. Photobiol., A. 384, 112040 (2019).

Liu, E. et al. Cisplatin loaded hyaluronic acid modified TiO2 nanoparticles for neoadjuvant chemotherapy of ovarian cancer. J. Nanomaterials. 2015 (1), 390358 (2015).

Chen, Y. C., Prabhu, K. S. & Mastro, A. M. Is selenium a potential treatment for cancer metastasis? Nutrients 5 (4), 1149–1168 (2013).

Korfi, F. et al. The effect of SP/NK1R on the expression and activity of catalase and superoxide dismutase in glioblastoma cancer cells. Biochem. Res. Int. 2021, p6620708 (2021).

Rezaei, S. et al. The therapeutic potential of aprepitant in glioblastoma cancer cells through redox modification. Biomed. Res. Int. 2022, p8540403 (2022).

Einafshar, E. et al. New cyclodextrin-based nanocarriers for drug delivery and phototherapy using an Irinotecan metabolite. Carbohydr. Polym. 194, 103–110 (2018).

Hummers, W. S. Jr & Offeman, R. E. Preparation of graphitic oxide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 80 (6), 1339–1339 (1958).

Einafshar, E. et al. Synthesis of new biodegradable nanocarriers for SN38 delivery and synergistic phototherapy. Nanomed. J. 5 (4), 210–216 (2018).

Einafshar, E. et al. Synthesis and characterization of multifunctional graphene oxide with gamma-cyclodextrin and SPION as new nanocarriers for drug delivery. Appl. Chem. Today. 14 (51), 35–50 (2019).

Andiri Niza, S., Herman, S. & Abdul, M. Validation of Rosmarinic acid quantification using High- performance liquid chromatography in various plants. Pharmacogn. J., 14(1). (2022).

Tawfeeq, A. A. et al. Isolation, quantification, and identification of Rosmarinic acid, gas chromatography-mass spectrometry analysis of essential oil, cytotoxic effect, and antimicrobial investigation of Rosmarinus officinalis leaves. Asian J. Pharm. Clin. Res. 11 (6), 126–132 (2018).

Muzakkar, M. et al. High photoelectrocatalytic activity of selenium (Se) doped TiO2/Ti electrode for degradation of reactive orange 84. in Journal of Physics: Conference Series. IOP Publishing. (2021).

Li, K. et al. Advances in prostate cancer biomarkers and probes. Cyborg Bionic Syst. 5, 0129 (2024).

Jiang, C. H. et al. Anticancer activity and mechanism of Xanthohumol: a prenylated flavonoid from hops (Humulus lupulus L). Front. Pharmacol. 9, 530 (2018).

Jin, B. R. et al. Rosmarinic acid represses colitis-associated colon cancer: A pivotal involvement of the TLR4-mediated NF-κB-STAT3 axis. Neoplasia 23 (6), 561–573 (2021).

Zarei Shandiz, S. et al. The effect of SP/NK1R on expression and activity of glutaredoxin and thioredoxin proteins in prostate cancer cells. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 397 (8), 5875–5882 (2024).

Madureira, A. R. et al. Insights into the protective role of solid lipid nanoparticles on Rosmarinic acid bioactivity during exposure to simulated Gastrointestinal conditions. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces. 139, 277–284 (2016).

Bagher Hosseini, N. et al. Can paternal environmental experiences affect the breast cancer risk in offspring? A systematic review. Breast Dis. 42, 361–374 (2023).

Jaglanian, A., Termini, D. & Tsiani, E. Rosemary (Rosmarinus Officinalis L.) Extract Inhibits Prostate cancer Cell Proliferation and Survival by Targeting Akt and mTOR131p. 110717 (Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy, 2020).

Petiwala, S. M. et al. Rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis) extract modulates CHOP/GADD153 to promote androgen receptor degradation and decreases xenograft tumor growth. PLoS One. 9 (3), e89772 (2014).

Liu, H. et al. Rosmarinic acid in combination with ginsenoside Rg1 suppresses colon cancer metastasis via co-inhition of COX-2 and PD1/PD-L1 signaling axis. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 45 (1), 193–208 (2024).

Rezaei, S. et al. Unveiling the Promising Role of Substance P/Neurokinin 1 Receptor in Cancer Cell Proliferation and Cell Cycle Regulation in Human Malignancies (Curr Med Chem, 2024).

Aggarwal, V. et al. Role of reactive oxygen species in cancer progression: molecular mechanisms and recent advancements. Biomolecules, 9(11). (2019).

Khoshghamat, N. et al. The therapeutic potential of renin-angiotensin system inhibitors in the treatment of pancreatic cancer. Life Sci. 270, 119118 (2021).

Xu, Y. et al. Anti-invasion effect of Rosmarinic acid via the extracellular signal-regulated kinase and oxidation-reduction pathway in Ls174-T cells. J. Cell. Biochem. 111 (2), 370–379 (2010).

Ebrahimi, S. et al. SP/NK1R system regulates carcinogenesis in prostate cancer: shedding light on the antitumoral function of aprepitant. Biochim. Et Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Molecular Cell. Res. 1869 (5), p119221 (2022).

Kowalczyk, A., Tuberoso, C. I. G. & Jerković, I. The role of Rosmarinic acid in cancer prevention and therapy: mechanisms of antioxidant and anticancer activity. Antioxid. (Basel), 13(11). (2024).

Snezhkina, A. V. et al. ROS generation and antioxidant defense systems in normal and malignant cells. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2019, p6175804 (2019).

Yang, K. et al. Rosmarinic acid inhibits migration, invasion, and p38/AP-1 signaling via miR-1225-5p in colorectal cancer cells. J. Recept Signal. Transduct. Res. 41 (3), 284–293 (2021).

Ngo, S. N., Williams, D. B. & Head, R. J. Rosemary and cancer prevention: preclinical perspectives. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 51 (10), 946–954 (2011).

Areti, A. et al. Rosmarinic acid mitigates mitochondrial dysfunction and spinal glial activation in Oxaliplatin-induced peripheral neuropathy. Mol. Neurobiol. 55 (9), 7463–7475 (2018).

Jang, Y. G., Hwang, K. A. & Choi, K. C. Rosmarinic acid, a component of Rosemary tea, induced the cell cycle arrest and apoptosis through modulation of HDAC2 expression in prostate cancer cell lines. Nutrients, 10(11). (2018).

Han, Y. H., Kee, J. Y. & Hong, S. H. Rosmarinic acid activates AMPK to inhibit metastasis of colorectal cancer. Front. Pharmacol. 9, 68 (2018).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Elham Einafshar developed the conceptual framework for the study, designed the synthesis strategy, and managed the synthesis and characterization of the nanocomposite. The experimental design and planning were carried out by Maryam Hosseinzadeh Ranjbar, Hossein Javid, Reza Asaran Darban, Seyedeh Sara Sajjadi, and Niloufar Jafari. Hossein Javid also conducted the analysis of the experimental data. The initial manuscript was drafted collaboratively by Elham Einafshar, Niloufar Jafari, and Seyedeh Sara Sajjadi, with revisions contributed by Seyed Isaac Hashemy and Reza Asaran Darban. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript prior to submission.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hosseinzadeh Ranjbar, M., Einafshar, E., Javid, H. et al. Enhancing the anticancer effects of rosmarinic acid in PC3 and LNCaP prostate cancer cells using titanium oxide and selenium-doped graphene oxide nanoparticles. Sci Rep 15, 11568 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96707-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96707-y

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Enhancement of the protective effect of diosmin against glutamate-induced toxicity by selenium-chitosan nanoparticle formulation

Journal of Nanoparticle Research (2025)