Abstract

This study aims to explore the mediating role of psychological distress in the association between perceived burden and quality of life (QoL) in advanced cancer patient-caregiver dyads. 241 dyads in five tertiary hospitals in a province were investigated by using the Edmonton Symptom Assessment System, Zarit Burden Interview, the Patient Health Questionnaire-4, the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 15 Palliative scores, and the Short Form Health Survey 8. The actor-partner interdependence mediation model (APIMeM), which assesses both individual (actor) and interdependent (partner) effects within dyadic relationships, was employed to analyze how burden and psychological distress interact across dyad members. Analysis was conducted using Mplus v8.0. Regarding the actor effects, the mediating role of psychological distress between perceived burden and QoL was confirmed in advanced cancer patients (B = −0.223, p = 0.001) and their caregivers (B = −0.168, p < 0.001). Regarding the partner effects, there were no significant correlations between caregiver burden and patients’ psychological distress (B = 0.015, p = 0.199), patients’ QoL (B = 0.113, p = 0.278), or the indirect association of caregiver burden with patients’ QoL through psychological distress (B = −0.034, p = 0.259). However, caregivers’ psychological distress was positively correlated with patients’ symptom burden and mediated the association between patients’ symptom burden and caregivers’ QoL (B = −0.090, p = 0.001). The study highlights the importance of taking a dyadic perspective in the context of advanced cancer. Dyadic interventions targeting their perceived burden and psychological distress may be beneficial to their QoL.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The worldwide incidence of cancer, with China at the forefront, is witnessing a significant surge in both morbidity and mortality rates1. In 2020, global cancer-related fatalities approached an alarming 10 million, with China accounting for 3 million1. Many individuals annually progress to advanced disease stages, particularly those in clinical stages III and IV, unresponsive to curative treatments2. Palliative approaches, such as chemotherapy and radiation therapy, replace curative methods, aiming to mitigate symptoms and arrest disease progression3,4,5. These patients exhibit considerable symptomatology from both the malignancy and treatment side effects. Prior research identified pain, reduced appetite, and fatigue as dominant symptoms, occurring between 40.8 and 70.4%6, consistent with earlier studies7,8,9,10. Some symptoms, like prolonged fatigue11 and chemotherapy- induced peripheral neuropathy12, linger post-treatment. Given the multifaceted challenges from the disease and concomitant symptoms, patients often require caregiver support. Culturally influenced caregiving dynamics are notable in China, where Confucian ideals significantly shape familial responsibilities, including caregiving for ill family members13,14. In this cultural context, typically, two family members assist each advanced cancer patient15. The symptom load experienced by patients correlates with caregiver burden; notably, 65.3% of caregivers face considerable stress16. The severity of a patient’s symptoms directly impacts the caregiver’s stress magnitude16,17, with 41.3% of caregivers enduring continuous heightened caregiver burden18.

Previous research conclusively shows that burden perceived by advanced cancer patients and their caregivers diminish their quality of life (QoL)7,19. Patients grapple with disease symptoms, treatment discomfort, and uncertainties, significantly affecting QoL7. Concurrently, caregivers manage daily care, emotional support, and psychological burden, detrimentally impacting their QoL19. Studies reveal a moderate positive correlation between the QoL of patients and caregivers20,21,22, emphasizing that cancer, as a shared familial experience, reciprocally affects both parties’ well-being. This intertwined relationship is complex, shaped by emotional connections, family dynamics, coping mechanisms, and the cultural context of Confucian ideals and filial piety13,14, crucial for improving comprehensive cancer care and bolstering the QoL of both patients and caregivers.

Existing literature highlights the intricate relationship between symptom and caregiver burden and psychological distress in cancer care23,24,25,26. Research reveals a significant correlation between the symptom burden in advanced cancer patients and the onset of psychological distress, including anxiety and depression23,24. Caregivers with heightened caregiving loads exhibit amplified psychological distress levels, especially depression25,26, with the distress fluctuating according to changes in the patient’s health27. Further studies identify a positive correlation between the psychological distress of patients and caregivers28.

While prior research has elucidated the impact of symptom and caregiver burden as well as psychological distress on QoL7,19,29, there’s been limited exploration of the dyadic relationship between these variables among patients and caregivers. Existing knowledge lacks clarity on the relationships and mechanisms within these dyads. According to Lazarus’s stress-coping theory30, in the context of advanced cancer, stress (cancer-related burden) influences the coping process (psychological distress), ultimately impacting health outcomes (QoL). In this model, psychological distress is typically considered a component of the coping process, representing the emotional and cognitive responses of individuals to stress30. However, prior research has mainly focused on individual experiences. In this study, employing the actor-partner interdependence mediation model (APIMeM), we aim to analyze the dyadic interplay between advanced cancer patients and their caregivers comprehensively. The aim is to discern how cancer-related burden influences QoL through the mediation of psychological distress within this dyadic relationship.

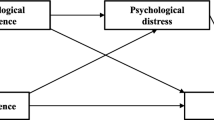

Drawing upon stress-coping theory30, we hypothesize that the burden experienced by patients and caregivers influences their individual QoL both directly and through the mediation of psychological distress. Furthermore, we propose the existence of a dyadic actor-partner interdependence mechanism to identify actor effects (e.g., patients’ symptom burden correlates with their own QoL) and partner effects (e.g., patients’ symptom burden correlates with caregivers’ QoL). A graphical representation of this theoretical framework can be found in Fig. 1. Our hypotheses were as follows:

H1: The cancer-related burden reported by patients and caregivers will be negatively associated with their own QoL and the QoL of the other member of the dyad.

H2: The cancer-related burden reported by patients and caregivers will be positively associated with their own psychological distress and the psychological distress of the other member of the dyad.

H3: Psychological distress reported by patients and caregivers will be negatively associated with their own QoL and the QoL of the other member of the dyad.

H4: The cancer-related burden will have a negative association with QoL (mediated by psychological distress).

Methods

Design and settings

We conducted a multi-center cross-sectional study between June 2020 and March 2021 in oncology wards in five tertiary hospitals in Henan Province, China.

We employed a meticulous approach to the selection of hospitals, considering various factors to ensure a comprehensive representation across the province. Geographical diversity was a primary focus, guiding us to strategically choose five hospitals situated in the west, central, east, and south regions. All selected hospitals are top-tier “Grade 3, Level A” facilities according to the hospital grading system established by the Chinese National Health Commission31. These institutions are recognized for their medical expertise, comprehensive range of services, and capacity to deliver high-quality care. This deliberate selection aimed at capturing a diverse patient demographic, including both urban and rural populations, while ensuring that the hospitals met the highest standards of clinical care and expertise. Furthermore, the inclusion of these top-tier institutions was essential for ensuring robust clinical and research capabilities. This approach allowed us to maintain high standards of care while capturing a broad range of patient experiences, which is crucial for investigating the complex relationships between perceived burden, psychological distress, and QoL in advanced cancer patient-caregiver dyads.

Participants

To facilitate participant recruitment, five skilled research assistants, each a registered nurse assigned to one of the hospitals, employed convenience sampling to enlist advanced cancer patients and their primary caregivers. Eligibility criteria encompassed advanced cancer patients aged 18 or older, diagnosed with stage IV cancer, including prevalent solid malignancies such as lung cancer, breast cancer, esophageal cancer, and colorectal cancer, as well as hematologic malignancies like lymphoma. Participants were required to provide informed consent for participation. Before commencing the investigation, we meticulously reviewed the staging protocols of each hospital and initiated discussions with oncologists to align the interpretation and application of staging criteria across all sites. This collaborative effort aimed to reduce discrepancies in the categorization of patients according to their cancer stage. Exclusions were applied to individuals with life-threatening severe physical illnesses or severe mental illnesses affecting cognitive function. Family caregivers, also 18 years or older, were included if identified by the patients as their primary caregiver without receiving compensation.

For structural equation modeling, a sample size of more than 200 is recommended to ensure adequate statistical power for reliable model estimation32. Consequently, we extended invitations to a total of 270 patient-caregiver pairs, resulting in a sample comprising 540 individuals. Our final dataset for analysis exclusively comprised complete patient-caregiver pairs, totaling 241 dyads. This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was granted by the Ethics Committee of Zhengzhou University (approval number: ZZUIRB 2021–19).

Data collection procedures

Data collection was conducted through paper–pencil based, self-administered questionnaires, completed independently by both advanced cancer patients and their caregivers. To minimize investigator bias, we engaged five trained research assistants, each stationed at a distinct hospital. All research assistants were registered nurses who provided standardized instructions to participants at the time of enrollment. Informed consent was scrupulously obtained from each participant before administering the questionnaire. Specifically, participants were fully informed about the study’s objectives, procedures, and potential risks through a detailed explanation provided in person. They were assured that their participation was voluntary and that they could withdraw at any time without any consequences. The consent process was conducted face-to-face, allowing participants to ask any questions and ensuring they fully understood the nature of the study. Written consent was obtained from all participants, confirming their agreement to participate. In instances where participants needed assistance, research assistants were available to orally present the questions and impartially record responses. Only dyads, in which both patient and caregiver actively participated, were considered for subsequent data analysis; incomplete dyads were excluded. To optimize participant engagement and response quality, questionnaires were administered in the afternoon, a time generally marked by fewer treatment-related activities. Research assistants remained available to clarify any ambiguities, ensuring participants had a clear understanding of the questionnaire content. Upon completion, research assistants meticulously reviewed the questionnaires to identify and rectify any missing data. They proactively addressed identified missing data by promptly contacting participants to ensure timely completion, thereby augmenting the effectiveness of the questionnaire recovery process. To maintain data integrity, questionnaires with more than 10% missing data or consistent response patterns were systematically excluded from the analysis.

Measures

Social-demographic and clinical characteristics

The demographic characteristics of advanced cancer patients and their family caregivers were investigated through a comprehensive questionnaire. This included inquiries into age, sex, marital status, educational background, employment status, and the monthly per capita household income. Patients were required to disclose their place of residence, while caregivers were tasked with providing information about their relationship with the patients, the presence of any chronic conditions, prior caregiving experience, the nature of caregiving (whether they were the sole caregivers or part of a caregiving team), the duration of caregiving, and the number of hours dedicated to caregiving each day.

For the clinical profile of patients, a thorough chart review was conducted. This encompassed aspects such as the method of medical expense payment, the primary cancer diagnosis, the duration since the diagnosis of advanced cancer, comorbidities assessment utilizing the Charlson comorbidity index (CCI), and evaluation of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (ECOG PS). Patients were categorized based on their ECOG PS, which comprises five grades, ranging from 0, indicating “completely normal activity ability,” to 4, signifying “bedridden and unable to care for oneself”33. A commonly applied ECOG PS threshold is 2, where a score of 0 to 2 indicates a favorable performance status34.

QoL

To assess patients’ QoL, we employed a single-item measure from the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 15 for Palliative Care (EORTC QLQ-C15 PAL), as recommended by prior studies35. Patients rated their overall QoL over the past week on a scale ranging from 1 (“very poor”) to 7 (“excellent”), with higher scores indicating better QoL. The raw scores were standardized, yielding a QoL score ranging from 0 to 100. In advanced cancer patients, the scale demonstrated excellent internal consistency, with a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.90036. To validate the measure, a known-group comparison approach was used, confirming good validity through statistically significant correlations between lower QoL scores and poorer performance status36,37. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.819 in this study.

For caregivers, the 8-item Short Form 8 Health Survey (SF-8) was utilized, a tool initially developed by Ware et al. in 200138. Caregivers assessed their health status within the previous four weeks using a Likert scale, which consisted of 5 or 6 levels for each item. Each item evaluated a distinct health dimension. Raw scores were transformed into T-scores, centered around a mean of 50 with a standard deviation of 10, yielding a range from 0 to 100. The SF-8 produced two summary scores: the Physical Component Summary (PCS) and the Mental Component Summary (MCS)38. Aggregate scores were calculated as the mean across all dimensions, with higher scores signifying improved health status38. The SF-8 was translated into Chinese by Wang et al., and in a Chinese adult health population, it demonstrated a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.749, with a correlation coefficient of 0.559 between the SF-8 and SF-36. Factor analysis revealed three components—mental health, physical health, and overall health—accounting for 71.71% of the scale’s total variance39. In this study, the overall aggregate score of SF-8 was used, and the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was determined to be 0.871.

Caregiver burden

To assess caregiver burden, we utilized the Zarit Burden Interview (ZBI), a 22-item instrument initially developed by Zarit et al. in 198040 and translated into Chinese by Wang in 200641. The ZBI focuses on two core dimensions: personal burden, exemplified by questions such as “Do you feel your relative asks for more help than he/she needs?” and role burden, characterized by questions like “Has caring for the patient affected your relationships with family and friends?” Participants responded on a scale of 0 to 4, where 0 signifies minimal burden and 4 indicates severe burden40. The aggregate score could range from 0 to 88, with higher scores indicating greater caregiver burden. The scale’s test–retest reliability is 0.71, with Cronbach’s alpha coefficients ranging from 0.88 to 0.9240. The Chinese version of the ZBI demonstrated a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.87 and effectively differentiates caregiving burden across groups with varying levels of activities of daily living functioning in care recipients, confirming its good known-group validity41. The caregiver burden can be classified into three categories: mild burden (< 21 points), moderate burden (21–39 points), and severe burden (> 39 points)42. In our study, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for internal consistency was 0.900.

Symptom burden

To measure symptom burden in advanced cancer patients, we employed the Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESAS)43. Developed by Bruera et al. in 1991, the ESAS has been psychometrically validated and translated into over 20 languages44. Later, Watanabe et al. revised the ESAS, resulting in the ESAS-r45, which evaluates nine common symptoms and offers the option to include a tenth if applicable. We opted to incorporate constipation as the tenth symptom, considering its high prevalence among advanced cancer patients. Symptoms were rated on an 11-point numerical scale, ranging from 0 (no symptom presence or optimal condition) to 10 (worst possible condition). Intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) were calculated to assess rating consistency, which ranged from 0.65 to 0.8345. The Chinese version of ESAS showed acceptable internal consistency with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.72 and robust concurrent validity, demonstrated by correlation coefficients between 0.70 and 0.96 when compared to the M.D. Anderson Symptom Inventory scores46. In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for internal consistency reached 0.913.

Psychological distress

To evaluate the psychological distress experienced by advanced cancer patients and their caregivers, we employed the Patient Health Questionnaire-4 (PHQ-4), an instrument designed by Kroenke et al. in 200947. The simplified Chinese version of the PHQ-4 was obtained from https://www.phqscreeners.com, accessed on 1 May 2020. This brief tool comprises four items, divided into two subscales: one for measuring depressive symptoms and another for gauging anxiety levels. Participants were asked, “Over the past two weeks, how often have you experienced the following symptoms?” Response options varied from 0, denoting “not at all”, to 3, representing “nearly every day”. The subscale scores for depression and anxiety could each range from 0 to 6, resulting in an overall PHQ-4 score range of 0 to 12. A suggested sub-scale cutoff of ≥ 3 is recommended as a screening threshold for depression or anxiety. Among the 2149 patients tested, a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.85 was obtained47. The simplified Chinese version of the PHQ-4 demonstrated acceptable inter-factor, factor-total, and construct validity48. Moderate to high inter-factor and factor-total correlations, ranging from 0.393 to 0.903, were observed. Most correlations between the PHQ-4, its subscales, and other measures were greater than 0.30048. The simplified Chinese version showed acceptable to excellent reliability, with Cronbach’s alpha coefficients ranging from 0.818 to 0.919, McDonald’s omega from 0.895 to 0.916, and ICCs between 0.505 and 0.71748. In our study, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for internal consistency was 0.902 for patients and 0.866 for caregivers, confirming the instrument’s reliability.

Statistical analysis

Data compilation and validation were performed using Epidata v 3.1, with two researchers (Cui P and Cheng C) overseeing the process to ensure accuracy. Statistical analyses were conducted utilizing IBM SPSS version 21.0 and Mplus version 8.0. Initial analysis generated descriptive statistics to profile the respondents, categorizing all variables and reporting frequencies and percentages. According to the distribution of data, Pearson correlation analyses were employed to examine the relationships among burden, psychological distress, and QoL within patient-caregiver dyads. Guided by stress-coping theory30, this study conceptualizes cancer-related burden as a stressor, psychological distress as an individual’s cognitive and emotional response to stress, and QoL as the health outcome. The APIMeM was subsequently employed using Mplus version 8.0 to examine dyadic interdependence in these processes. This model distinguishes between actor effects (i.e., how an individual’s burden influences their own psychological distress and QoL) and partner effects (i.e., how an individual’s burden influences their partner’s psychological distress and QoL).

Within the APIMeM, psychological distress served as the mediator, while QoL functioned as the dependent variable, and patient symptom burden and caregiver burden were treated as independent variables. To refine the precision of the results, a bootstrap method featuring 5000 resampling iterations was employed to adjust the 95% confidence intervals of the effect sizes, a technique robust for interval estimation even with non-normally distributed data. Mediation effects were identified as present if the confidence interval excluded zero, and absent if it included zero. Model fit assessment relied on several parameters: the chi-squared value, the chi-squared degrees of freedom ratio (χ2/df), the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), the Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), and the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA). Model fit was considered acceptable when χ2/df was below 3, CFI and TLI exceeded 0.90, and RMSEA was under 0.0849,50.

Results

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics

A total of 270 dyads were recruited, and the data of 241 dyads were included in the final analyses, yielding a response rate of 89.3%. Among the 29 excluded dyads, 10 were incomplete (with either the patient or caregiver completing the questionnaire), 5 exhibited patterned responses, and 3 had missing items exceeding 10%.

Table 1 presents the characteristics of advanced cancer patients and their caregivers, reproduced from our previous publication51. The patients had a mean age of 53.96 years (SD 15.37), while caregivers had a mean age of 45.18 years (SD 13.79). Gender distribution disparities were evident, with males marginally more prevalent among patients and females among caregivers. Marriage prevailed in both groups, with proportions of 85.5% for patients and 87.1% for caregivers. Notably, affiliations varied, with 39.0% of caregivers being adult children. Patients displayed relatively lower educational attainment compared to caregivers. Solid tumors constituted the majority (72.6%) of primary cancer diagnoses, notably encompassing lung (21.2%), breast (9.1%), and digestive system cancers (27.4%) among 241 cases. Conversely, blood tumors accounted for 27.4% (66/241), primarily comprising lymphoma (22.8% of cases, n = 55) (see Supplementary Table S1).

Scores on various variables are shown in Table 2, and corresponding classifications can be found in the Additional file. Patients exhibited higher levels of psychological distress compared to caregivers (paired sample t-test: t = 2.938, p = 0.004). A notable 78% of caregivers reported experiencing a moderate-to-high burden, as detailed in Supplementary Table S2. Regarding the sub-dimensions of psychological distress, 27.8 and 21.2% of patients exceeded the threshold for depression and anxiety, respectively. Among caregivers, 13.3 and 17.4% surpassed the thresholds for depression and anxiety, respectively. It is noteworthy that the incidence of depression and anxiety is higher in patients than in caregivers (Supplementary Table S3).

Correlation analysis of different variables among patients and caregivers

At the individual level, patient symptom burden and psychological distress demonstrated a negative correlation with their QoL (r = −0.496, -0.452, respectively, p < 0.01). Moreover, symptom burden exhibited a positive correlation with psychological distress (r = 0.629, p < 0.01). For caregivers, their QoL exhibited a negative correlation with caregiver burden and psychological distress (r = −0.449, −0.543, respectively, p < 0.01). Additionally, caregiver burden exhibited a positive correlation with psychological distress (r = 0.337, p < 0.01).

At the dyad level, a positive correlation emerged between patients’ and caregivers’ psychological distress (r = 0.342, p < 0.01) and QoL (r = 0.157, p < 0.05). Conversely, caregivers’ psychological distress showed a negative correlation with patients’ QoL (r = −0.189, p < 0.01), whereas patients’ symptom burden and psychological distress displayed a negative correlation with caregivers’ QoL (r = −0.263, −0.206, p < 0.01, respectively). Furthermore, patients’ symptom burden exhibited a positive correlation with caregivers’ psychological distress (r = 0.239, p < 0.01). Patients’ psychological distress displayed a positive correlation with caregivers’ burden (r = 0.144, p < 0.05), as illustrated in Table 3.

Actor-partner interdependence mediation model analysis

Notably, this study observed the APIMeM’s fit parameters: χ2/df = 2.504, CFI = 0.979, TLI = 0.929, and RMSEA = 0.079 (90% confidence interval, 0.029–0.130), indicative of an acceptable model fit. The results of the APIMeM analysis were showed in Table 4 and Fig. 2.

APIMeM results of cancer-related burden and psychological distress on quality of life in advanced cancer patient-caregiver dyads. Estimates are standardized; significant parameter estimates are indicated in bold, and significant paths are illustrated with solid lines, while non-significant paths are depicted with dashed lines. Model fit indices: χ2 = 15.026; df = 6; p = 0.020; χ2/df = 2.504; CFI = 0.979; TLI = 0.929; RMSEA = 0.079 (90% Confidence interval: 0.029–0.130). *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

H1: Cancer-related burden → QoL. Higher burden reported by patients and caregivers were associated with lower QoL (actor effects). Specifically, there was a negative relationship between patient symptom burden and their QoL (β = -0.417, p < 0.001). Similarly, a negative association between caregiver burden and QoL was identified in caregivers (β = −0.356, p < 0.001). Moreover, patient symptom burden exerted a negative partner effect on caregiver QoL (β = −0.155, p = 0.006), while the association between caregiver burden and patients’ QoL was non-significant (β = 0.113, p = 0.278). H2 received partial support.

H2: Cancer-related burden → Psychological distress. Higher cancer-related burden in patients and caregivers were associated with higher psychological distress (actor effects). Significant positive relationships were observed between symptom burden among advanced cancer patients and psychological distress (β = 0.100, p < 0.001), as well as between higher caregiver burden and heightened psychological distress (β = 0.066, p < 0.001). Additionally, elevated symptom burden in patients was correlated with in increased psychological distress in caregivers (partner effect) (β = 0.035, p < 0.001). However, caregiver burden exhibited no significant correlation with patients’ psychological distress (β = 0.015, p = 0.199). H1 was partially supported.

H3: Psychological distress → QoL. As hypothesized, higher psychological distress was associated with lower QoL in both patients and caregivers (actor effects). Specifically, patient psychological distress was negatively associated with their QoL (β = −2.226, p < 0.001). Similarly, higher psychological distress was associated with a diminished QoL (β = −2.536, p < 0.001). However, neither patient nor caregiver psychological distress were significantly associated with decreases in the QoL of their counterparts (β = 0.288, p = 0.461; β = −0.089, p = 0.871, respectively). H3 was partially supported.

H4: Indirect effects of cancer-related burden on QoL. Patient symptom burden manifests an indirect and negative association with QoL through the conduit of their psychological distress (actor effects) (β = −0.223, p = 0.001). Similarly, caregiver burden was indirectly correlated with their QoL through the mediation of psychological distress (actor effects) (β = −0.168, p < 0.001). Moreover, patient symptom burden indirectly correlated with caregiver QoL through the mediation of caregiver psychological distress (partner effects) (β = −0.090, p = 0.001). However, the association between caregiver burden and patients’ QoL via patients’ psychological distress was non-significant (β = −0.034, p = 0.259). H4 was partially supported.

Discussion

This study examined the intertwined relationships of cancer-related burden (symptom burden, caregiver burden), psychological distress, and QoL within dyads of advanced cancer patients and their caregivers. Building on prior work, it further investigated the role of psychological distress as a potential mediator within these dyads. The hypothetical model was partially supported. Regarding actor effects, the results showed that both patients’ and caregivers’ QoL were directly and indirectly correlated with their individual burden, mediated through their respective psychological distress. In terms of partner effects, only patients’ symptom burden exhibited a direct and indirect correlation with caregivers’ QoL through caregivers’ psychological distress. In contrast, caregiver burden did not show a significant direct or indirect association with patients’ QoL. These findings align with the dyadic application of the stress and coping theory.

In our study, QoL scores for advanced cancer patients fell below those reported for late-stage breast cancer patients by Gayatri et al. (78.02 ± 15.34)52, but exceeded Koyama et al.’s findings for terminal cancer patients (38.7 ± 27.1)21. Our sample predominantly consisted of patients diagnosed with advanced cancer in the past year, including both solid tumors and hematologic malignancies. This sample heterogeneity, relative to prior studies, could stem from various factors. For example, Gayatri et al. centered their research on stage III-IV breast cancer patients, who may have had better functional statuses52, whereas Koyama et al. focused on terminal patients with declining health and limited life expectancy21. We also found that caregivers’ QoL scores were slightly higher than those in Wang et al.’s study on advanced lung cancer caregivers (71.28 ± 18.16)22, and markedly surpassed those in Ullrich et al.’s research (42.2 ± 7.1)53. Notably, 78% of caregivers reported a moderate-to-high caregiving burden, which aligns with the significant symptom burden observed among the advanced cancer patients in our study, comparable to findings by Paiva et al.54. Moreover, patients demonstrated elevated levels of psychological distress and higher frequency of depression and anxiety compared to caregivers. These outcomes underscore the need for a comprehensive, dyadic approach in nursing care that considers the complexities of cancer type, functional capacity, psychological health, and caregiving dynamics. Targeting these variables could improve QoL for both advanced cancer patients and their caregivers.

Our study suggests that the symptom burden in advanced cancer patients and the caregiving burden in caregivers correlate positively with their respective QoL, aligning with prior research7,19. Such patients often grapple with significant symptom burden due to both the disease and treatment side effects7,8,9,10. These severe symptoms can expedite a decline in the patient’s functional capacity, resulting in diminished QoL. In China, where Confucian ideals significantly shape societal norms, caregivers predominantly bear the familial duty of offering continuous care to advanced cancer patients13,14. This cultural tenet underscores the sanctity of familial relationships, prompting relatives to tend to the sick. Consequently, in this societal backdrop, caregivers habitually prioritize patients’ needs, ensuring their daily comfort, emotional welfare, and overall well-being. This ingrained cultural ethic compels caregivers to consistently provide care, which, though noble, places them under enormous stress, arguably more than counterparts in other cultures, impacting their QoL negatively19. Notably, culture may exert a positive influence by fostering resilience in caregivers through the promotion of family cohesion and caregiver satisfaction55. In future endeavors, a more nuanced exploration of both the positive and negative impacts of cultural factors on caregivers could be conducted to provide a more holistic understanding of the intricate dynamics involved in caregiving within traditional cultural contexts.

Our data aligns with prior research in demonstrating a negative correlation between patients’ symptom burden and caregivers’ QoL56. However, it diverges from some earlier studies57,58 by revealing no significant link between caregivers’ burden and patients’ QoL. This discrepancy may be attributed to patients focusing on their own symptoms, thereby overlooking caregiver strain59. Shin et al. found that such underestimation correlates with lower caregiver QoL and heightened anxiety and depression60. These results point to the potential effectiveness of interventions designed to raise patients’ awareness of caregiver strain, fostering mutual empathy. Moreover, caregiver burden reflects not just the duties of caregiving but also the inherent challenges of the role, which, if pronounced, can degrade care quality and result in adverse patient outcomes61.

The mediation analysis in our study revealed that psychological distress partially mediated the “actor effects” between burden and QoL for both advanced cancer patients and their caregivers. This finding aligns with previous research indicating that heightened psychological distress adversely affects patients’ QoL23,24,62 and psychological distress is a mediator between stressors and QoL63. Moreover, our study extends the literature by establishing a mediating role of caregivers’ psychological distress between their caregiving burden and QoL, reinforcing earlier evidence of positive associations among these variables29,64. These results illuminate the critical role of psychological distress in the nexus between burden and QoL for both members of the patient-caregiver dyad. Accordingly, we recommend the incorporation of emotional management interventions, supported by the evidence that cognitive (e.g., cognitive reframing, effective coping skills training, anger management) or psycho-educational strategies (i.e., counseling, education, behavioral therapy, and social support) can positively affect QoL65 and mitigate depressive symptoms65,66.

Concerning “partner effects,” we observed a significant correlation between increased patient symptom burden and elevated caregiver psychological distress, which in turn partially mediated the impact on caregiver QoL. Various factors such as emotional attachment, sense of responsibility, extensive time investment, and lack of social support could contribute to this mediation67. To enhance caregiver QoL, interventions including coping strategies, social support, and improved communication between patients and caregivers are advised68. However, unlike some previous studies57,58, we did not find a consistent relationship between caregiver burden, patients’ psychological distress, and patients’ QoL. This discrepancy may be due to the possibility that patients’ psychological distress is more tightly bound to their personal illness experience23,24. Such divergence necessitates a more in-depth and careful examination of the emotional dynamics between patients and caregivers. Accordingly, healthcare practitioners are encouraged to foster open dialogue to collaboratively develop individualized care plans. Furthermore, influenced by Chinese culture, patients may perceive a sense of entitlement to care which could serve as a protective factor against diminished QoL or increased distress in response to caregiver burden13,14. Culture beliefs and expectations should be considered to effectively support patients and caregivers in clinical practice.

Strengths and limitations

From a dyadic standpoint that includes both advanced cancer patients and their caregivers, our study enriches existing literature by elucidating the mediating role of psychological distress in the relationship between cancer-related burden and QoL. Our findings extend beyond previous research by identifying both individual-level “actor-mediated” and dyadic-level “partner-mediated” pathways.

However, there are several limitations. Firstly, its cross-sectional design precludes the establishment of causal relationships and allows for the possibility of alternative variable orderings. To address this, future research should adopt a longitudinal design, examining these variables at various time points and exploring alternative mediation paths. Secondly, our results did not show a significant influence of caregiver burden on patient psychological distress and QoL, a divergence from some previous findings. Future inquiries might employ qualitative methods to explore the underlying reasons for this discrepancy, thereby deepening our understanding of the patient-caregiver dyad. Thirdly, demographic variables like age, gender, and education level, as well as disease-specific features, like hematologic vs. solid tumors, which may be linked to QoL, were not controlled in this study. It is recommended that future research addresses these variables and conducts subgroup analyses, enriching research outcomes and informing more targeted interventions. Additionally, due to incomplete general information, we refrained from directly comparing excluded and included dyads, potentially introducing bias. Despite efforts to ensure consistency in applying clinical staging criteria, variations may persist across participating hospitals, potentially influencing the categorization of patients based on cancer stage. This should be considered when interpreting results.

As for the generalizability of the findings, our study specifically targets a province, selecting hospitals with the aim of collectively representing broader characteristics of cancer patients in the region. This approach allows us to capture typical features, such as gender distribution, major cancer types, and urban–rural ratios, observed in cancer patients from our province (Central China). Additionally, the types and incidence rates of major solid tumors studied in our research partly mirror the characteristics of prevalent malignancies in the overall cancer population in China. However, it is essential to acknowledge that the generalizability of our findings to the entire country and worldwide may be limited due to differences in the age structure. Approximately one-third of advanced cancer patients in our study are aged 60 and above, with an average age of around 54 years. This contrasts with the peak incidence of cancer in our province69 and the entire country70, which occurs in the 80–84 age group, and the global median incidence (66 years old)1. This age distribution variance may introduce limitations when extrapolating our study results to represent the broader cancer population, particularly for elderly individuals suffering from advanced cancer. Future research endeavors should consider expanding the sample size to encompass a more representative demographic profile, including age, gender, cancer types, and geographical locations, to achieve a more comprehensive understanding of the characteristics and needs of cancer patients in both China and globally.

Conclusions

Our study identifies mediating effects at the individual level, emphasizing a mediation link between symptom burden, psychological distress, and QoL for both advanced cancer patients and their caregivers. Essentially, the perception of symptom or caregiver burden by patients and caregivers can be correlated with their own QoL through individual experiences of psychological distress. At a dyadic level, patients’ symptom burden indirectly associates with caregivers’ QoL through the mediation of caregivers’ psychological distress. This study underscores the importance of considering the holistic well-being of patients and caregivers in clinical nursing, recognizing the complex interplay between symptom burden and QoL. It suggests that adopting collaborative interventions—addressing symptom burden, providing evidence-based emotional support, and offering family-centered programs, while also balancing cultural expectations—clinicians can enhance QoL for both patients and caregivers. These insights can significantly improve clinical nursing practices, better supporting the unique needs of advanced cancer patients and their caregivers.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this manuscript and its supplementary information files. The datasets are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Sung, H. et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 71, 209–249 (2021).

Broeckaert, B. & Olarte, J. The ethics of palliative care. European perspectives (Open University Press, 2002).

Stegmann, M. E., Geerse, O. P., van Zuylen, L., Nekhlyudov, L. & Brandenbarg, D. Improving care for patients living with prolonged incurable cancer. Cancers (Basel) 13, 2555 (2021).

Baek, S. K., Kim, S. Y., Heo, D. S., Yun, Y. H. & Lee, M. K. Effect of advanced cancer patients’ awareness of disease status on treatment decisional conflicts and satisfaction during palliative chemotherapy: a Korean prospective cohort study. Support Care Cancer 20, 1309–1316 (2012).

Kitta, A. et al. The silent transition from curative to palliative treatment: a qualitative study about cancer patients’ perceptions of end-of-life discussions with oncologists. Support Care Cancer 29, 2405–2413 (2021).

Abstracts for MASCC/ISOO Annual Meeting 2019. Support Care Cancer, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-019-04813-1 (2019).

Kokkonen, K. et al. Cancer patients’ symptom burden and health-related quality of life (HRQoL) at tertiary cancer center from 2006 to 2013: A cross-sectional study. Anticancer Res. 39, 271–277 (2019).

Raijmakers, N. J. H. et al. Health-related quality of life among cancer patients in their last year of life: results from the PROFILES registry. Support Care Cancer 26, 3397–3404 (2018).

Grotmol, K. S. et al. Depression-a major contributor to poor quality of life in patients with advanced cancer. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 54, 889–897 (2017).

Rojas-Concha, L., Hansen, M. B., Petersen, M. A. & Groenvold, M. Symptoms of advanced cancer in palliative medicine: a longitudinal study. BMJ Support Palliat. Care https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjspcare-2021-002999 (2021).

Peters, M. E., Goedendorp, M. M., Verhagen, C. A., Bleijenberg, G. & van der Graaf, W. T. Fatigue and its associated psychosocial factors in cancer patients on active palliative treatment measured over time. Support Care Cancer 24, 1349–1355 (2016).

Mols, F. et al. Chemotherapy-induced neuropathy and its association with quality of life among 2- to 11-year colorectal cancer survivors: results from the population-based PROFILES registry. J. Clin. Oncol. 31, 2699–2707 (2013).

Zarzycki, M., Seddon, D., Bei, E., Dekel, R. & Morrison, V. How culture shapes informal caregiver motivations: A meta-ethnographic review. Qual. Health Res. 32, 1574–1589 (2022).

Zarzycki, M., Morrison, V., Bei, E. & Seddon, D. Cultural and societal motivations for being informal caregivers: a qualitative systematic review and meta-synthesis. Health Psychol. Rev. 17, 247–276 (2023).

Shi, Y. X. & Gr, W. Research on the Current Situation and Policies of Hospice Care Services in Chinese (Shanghai Science and Technology Education Press, 2010).

Celik, E. et al. The relationship between symptom severity and caregiver burden in cancer patients under palliative care: A cross-sectional study. J. Palliat. Care 37, 48–54 (2022).

Semere, W. et al. Poor patient health is associated with higher caregiver burden for older adults with advanced cancer. J. Geriatr. Oncol. 12, 771–778 (2021).

See, J. W. F., Teo, E. A. I. & Malhotra, C. Longitudinal trajectories of caregiving experiences among primary informal caregivers of patients with metastatic solid cancer (stage IV). Psychooncology 31, 1161–1168 (2022).

Uzar-Ozceti, N. Y. & Dursun, S. I. Quality of life, caregiver burden, and resilience among the family caregivers of cancer survivors. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 48, 101832 (2020).

Yeh, Y. C., Sun, J. L. & Lu, C. H. Associations between perceived stress and quality of life in gynaecologic cancer patient-family caregiver dyads. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 55, 102060 (2021).

Koyama, N. et al. The role of EORTC QLQ-C15-PAL scores and inflammatory biomarkers in predicting survival in terminally ill patients with cancer. BMC Cancer 21, 304 (2021).

Wang, H., Yue, H., Ren, M. & Feng, D. Dyadic effects of family-functioning and resilience on quality of life in advanced lung cancer patients and caregivers: An actor-partner interdependence mediation model. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 52, 101963 (2021).

Teo, I. et al. High anxiety and depression scores and mental health service use among South Asian advanced cancer patients: A multi-country study. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 62, 997–1007 (2021).

Grotmol, K. S. et al. Patients with advanced cancer and depression report a significantly higher symptom burden than non-depressed patients. Palliat. Support Care 17, 143–149 (2019).

Govina, O. et al. Factors associated with anxiety and depression among family caregivers of patients undergoing palliative radiotherapy. Asia Pac. J. Oncol. Nurs. 6, 283–291 (2019).

Karabekiroglu, A., Demir, E. Y., Aker, S., Kocamanoglu, B. & Karabulut, G. S. Predictors of depression and anxiety among caregivers of hospitalised advanced cancer patients. Singapore Med. J. 59, 572–577 (2018).

Leow, M. Q. & Chan, S. W. The challenges, emotions, coping, and gains of family caregivers caring for patients with advanced cancer in Singapore: A qualitative study. Cancer Nurs. 40, 22–30 (2017).

Jacobs, J. M. et al. Distress is interdependent in patients and caregivers with newly diagnosed incurable cancers. Ann. Behav. Med. 51, 519–531 (2017).

Tan, J. Y., Molassiotis, A., Lloyd-Williams, M. & Yorke, J. Burden, emotional distress and quality of life among informal caregivers of lung cancer patients: An exploratory study. Eur. J. Cancer Care (England) 27, e12691 (2018).

Folkman, S., Lazarus, R. S., Gruen, R. J. & DeLongis, A. Appraisal, coping, health status, and psychological symptoms. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 50, 571–579 (1986).

China, N. H. C. Ministry of Health Office, “Implementation Rules for the Evaluation of Grade 3 Comprehensive Hospitals (2011 Edition)”, http://www.nhc.gov.cn/cms-search/xxgk/getManuscriptXxgk.htm?id=0404f9cd71764ab29b2365e069cfbf2d (2011).

Hoyle, R. H. & Gottfredson, N. C. Sample size considerations in prevention research applications of multilevel modeling and structural equation modeling. Prev. Sci. 16, 987–996 (2015).

Oken, M. M. et al. Toxicity and response criteria of the Eastern cooperative oncology group. Am. J. Clin. Oncol. 5, 649–655 (1982).

Cheng, S., Qureshi, M., Pullenayegum, E., Haynes, A. & Chan, K. K. Do patients with reduced or excellent performance status derive the same clinical benefit from novel systemic cancer therapies? A systematic review and meta-analysis. ESMO Open 2, e000225 (2017).

Groenvold, M. et al. The development of the EORTC QLQ-C15-PAL: a shortened questionnaire for cancer patients in palliative care. Eur. J. Cancer 42, 55–64 (2006).

Ozcelik, H., Guzel, Y., Sonmez, E., Aksoy, F. & Uslu, R. Reliability and validity of the Turkish version of the EORTC QLQ-C15-PAL for patients with advanced cancer. Palliat. Support Care 14, 628–634 (2016).

Zhang, L. et al. Cross-cultural verification of the EORTC QLQ-C15-PAL questionnaire in mainland China. Palliat. Med. 30, 401–408 (2016).

Ware, J. E., Kosinski, M., Dewey, J. E. & Gandek, B. How to Score and Interpret Single-Item Health Status Measures: A Manual for Users of the SF-8 Health Survey (Quality Metric Incorporated; Health Assessment Lab, 2001).

Wang, S. et al. Development and evaluation of Chinese version of short form 8. Mod. Prev. Med. (Chin.) 34, 1022–1024 (2007).

Zarit, S. H., Reever, K. E. & Bach-Peterson, J. Relatives of the impaired elderly: correlates of feelings of burden. Gerontologist 20, 649–655 (1980).

Wang, L., Yang, X. S., Hou, Z. & Feng, Q. L. Application and evaluation of Chinese version of zarit caregiver burden interview. Chin. J. Public Health 22, 970–972 (2006).

Hébert, R., Bravo, G. & Préville, M. Reliability, validity and reference values of the Zarit Burden Interview for assessing informal caregivers of community-dwelling older persons with dementia. Can. J. Aging Revue Canadienne Vieillissement 19, 494–507 (2000).

Bruera, E., Kuehn, N., Miller, M. J., Selmser, P. & Macmillan, K. The Edmonton symptom assessment system (ESAS): a simple method for the assessment of palliative care patients. J. Palliat. Care 7, 6–9 (1991).

Hui, D. & Bruera, E. The Edmonton symptom assessment system 25 years later: Past, present, and future developments. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 53, 630–643 (2017).

Watanabe, S. M. et al. A multicenter study comparing two numerical versions of the Edmonton symptom assessment system in palliative care patients. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 41, 456–468 (2011).

Dong, Y. et al. Psychometric validation of the Edmonton Symptom Assessment System in Chinese patients. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 50, 712–717 (2015).

Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., Williams, J. B. & Lowe, B. An ultra-brief screening scale for anxiety and depression: the PHQ-4. Psychosomatics 50, 613–621 (2009).

Meng, R. et al. Longitudinal measurement invariance and psychometric properties of the patient health questionnaire-four in China. BMC Psychiatry 24, 517 (2024).

Fabrigar, L. R., Porter, R. D. & Norris, M. E. Some things you should know about structural equation modeling but never thought to ask. J. Consum. Psychol. 20, 221–225 (2010).

Sivo, S. A., Fan, X., Witta, E. L. & Jt, W. The search for “optimal” cutoff properties: Fit index criteria in structural equation modeling. J. Exp. Educ. 74, 267–288 (2006).

Cui, P. et al. Family resilience and its influencing factors among advanced cancer patients and their family caregivers: a multilevel modeling analysis. BMC Cancer 23, 623 (2023).

Gayatri, D., Efremov, L., Mikolajczyk, R. & Kantelhardt, E. J. Quality of life assessment and pain severity in breast cancer patients prior to palliative oncology treatment in Indonesia: A cross-sectional study. Patient Prefer Adherence 15, 2017–2026 (2021).

Ullrich, A. et al. Quality of life, psychological burden, needs, and satisfaction during specialized inpatient palliative care in family caregivers of advanced cancer patients. BMC Palliat. Care 16, 31 (2017).

Paiva, C. E., Manfredini, L. L., Paiva, B. S., Hui, D. & Bruera, E. The Brazilian version of the Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESAS) is a feasible, valid and reliable instrument for the measurement of symptoms in advanced cancer patients. PLoS ONE 10, e0132073 (2015).

Canda, E. R. Filial piety and care for elders: A contested Confucian virtue reexamined. J. Ethn. Cult. Diversit. 22, 213–234 (2013).

Holgin, E. A., Arias-Rojas, M. & Moreno, S. C. Quality of life of family caregivers of people with cancer in palliative care. Rev. Esc. Enferm. USP 55, e03740 (2021).

Tang, S. T. et al. Patient awareness of prognosis, patient-family caregiver congruence on the preferred place of death, and caregiving burden of families contribute to the quality of life for terminally ill cancer patients in Taiwan. Psychooncology 17, 1202–1209 (2008).

An, Y., Fu, G. & Yuan, G. Quality of life in patients with breast cancer: The influence of family caregiver’s burden and the mediation of patient’s anxiety and depression. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 207, 921–926 (2019).

Leroy, T., Fournier, E., Penel, N. & Christophe, V. Crossed views of burden and emotional distress of cancer patients and family caregivers during palliative care. Psychooncology 25, 1278–1285 (2016).

Shin, J. Y. et al. Underestimated caregiver burden by cancer patients and its association with quality of life, depression and anxiety among caregivers. Eur. J. Cancer Care (England) 27, e12814 (2018).

Liu, Z., Heffernan, C. & Tan, J. Caregiver burden: A concept analysis. Int. J. Nurs. Sci. 7, 438–445 (2020).

Mystakidou, K. et al. Assessment of anxiety and depression in advanced cancer patients and their relationship with quality of life. Qual. Life Res. 14, 1825–1833 (2005).

Faul, L. A., Jim, H. S., Williams, C., Loftus, L. & Jacobsen, P. B. Relationship of stress management skill to psychological distress and quality of life in adults with cancer. Psychooncology 19, 102–109 (2010).

Van Hof, K. S. et al. Caregiver burden, psychological distress and quality of life among informal caregivers of patients with head and neck cancer: A longitudinal study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19, 1873–1881 (2022).

Stagl, J. M. et al. Long-term psychological benefits of cognitive-behavioral stress management for women with breast cancer: 11-year follow-up of a randomized controlled trial. Cancer 121, 1873–1881 (2015).

Wang, Y. et al. Effects of Internet-based psycho-educational interventions on mental health and quality of life among cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Support Care Cancer 28, 2541–2552 (2020).

Valeberg, B. T. & Grov, E. K. Symptoms in the cancer patient: of importance for their caregivers’ quality of life and mental health?. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 17, 46–51 (2013).

Kleine, A.-K., Hallensleben, N., Mehnert, A., Hönig, K. & Ernst, J. Psychological interventions targeting partners of cancer patients: A systematic review. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 140, 52–66 (2019).

Henan Cancer Center. 2022 Annual Report on Cancer Registration in Henan Province https://www.anti-cancer.com.cn/Hospitals/Journals/ArticleIndex/2103 (2023).

Zheng, R. S. et al. Cancer statistics in China, 2016. Chin. J. Oncol. 45, 212–220 (2023).

Acknowledgements

We thank all participants, families, and healthcare staff in our surveys.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. P. P. C., J. S. A., X. Y. C., C. Y. C., J. X. S., S.F.L., M. Y. performed material preparation, data collection and analysis. P. P. C., H. Y. H. prepared the first draft of the manuscript. C. Y. C., H. Y. H. performed critical review of the manuscript. All authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cui, P., Ai, J., Chen, X. et al. Dyadic effects of perceived burden and psychological distress on quality of life among Chinese advanced cancer patients and their caregivers. Sci Rep 15, 12180 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96861-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96861-3