Abstract

The urgent need for sustainable energy conversion technologies has propelled the development of efficient and cost-effective electrocatalysts for water splitting. In this study, we synthesize carbon-coated NiCoO2/NiCo@C composites through the calcination of CoNi Prussian Blue Analogues nanocubes, aiming to enhance the electrocatalytic performance for both oxygen evolution reaction (OER) and hydrogen evolution reaction (HER). Our findings demonstrate that the NiCoO2/NiCo@C composites exhibit outstanding catalytic activity, achieving low overpotentials of 329 mV for OER and 61.9 mV for HER at a current density of 10 mA cm−2, with robust stability under prolonged operational conditions. The enhanced activity is attributed to the large interface area and high density of exposed active sites facilitated by the unique heterojunction structure of NiCoO2/NiCo particles embedded in carbon frameworks and nanotubes. This architecture not only prevents the agglomeration of metal nanoparticles but also promotes efficient electron and proton transfer, significantly boosting electrochemical performance. This study introduces a promising approach for designing high-performance, cost-effective electrocatalysts, paving the way for their application in industrial water electrolysis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Water electrolysis presents a sustainable solution for hydrogen production, leveraging the decomposition of water into oxygen and hydrogen gases through electrochemical reactions1,2. Key to this process are the oxygen evolution reaction (OER) and hydrogen evolution reaction (HER), which occur at the anode and cathode, respectively3. The effectiveness of these reactions is intrinsically linked to the properties of the electrocatalysts employed, which dictate the overall energy efficiency and viability of the electrolysis under industrial condition4,5.

Recent advances in electrocatalysis have increasingly focused on the utilization of transition metals like cobalt (Co)6 and nickel (Ni)7, which are not only abundant and economical but also exhibit remarkable electrical conductivity and chemical stability8,9,10. Among these, CoNi nanoalloys have emerged as superior candidates for OER and HER due to their enhanced electrocatalytic properties and their crucial role in facilitating the cleavage of the HO–H bond, thus serving as effective bifunctional catalysts11,12. To further augment the activity of these nanoalloys, researchers have employed various strategies such as nanoparticle size reduction, intricate morphological tailoring, doping with non-metallic atoms, and the use of conductive supports13,14,15,16. However, manipulating the metal composition often proves more straightforward than precisely controlling the size and morphology of the nanoparticles17,18. For instance, nickel oxide (NiO), known for its low cost and wide availability, has seen modifications in its structural size and surface microstructure to enhance its catalytic capabilities. A pioneering approach by Ito et al.17 involved the synthesis of porous NiO nanoparticles with adjustable pore sizes through a simplified annealing process, which, despite its simplicity, led to partial agglomeration of the nanomaterials. Addressing this, Wang et al. enhanced NiOx’s activity by integrating it onto the surface of bamboo-shaped carbon nanotubes, thus optimizing the utilization of active sites and increasing the surface area available for catalysis19.

The transformation of Ni in CoNi Prussian blue analogues (PBA) to NiO represents another avenue for improving catalytic activity. However, challenges such as the aggregation of nanoalloys can diminish the exposure of active sites and reduce the efficiency of electron and proton transfers, ultimately compromising the stability and efficacy of the catalyst20,21,22. To counter these issues, conductive supports like carbon cloth, carbon nanotubes, graphene, and activated carbon are employed to evenly disperse the nanoalloys. Among these materials, carbon nanotubes are particularly valued for their exceptional stability, electrical conductivity, and their ability to adhere strongly to catalyst particles, creating a multifunctional design that enhances electrocatalytic performance23,24.

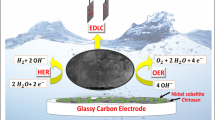

In our study, we have developed a carbon-coated NiCoO₂/NiCo electrocatalyst through the high-temperature calcination of CoNi PBA. This novel material embeds NiCoO2/NiCo particles within a robust carbon framework and nanotubes, effectively mitigating the issue of metal agglomeration while facilitating enhanced electrical conductivity. The resulting electrocatalysts exhibit superior OER/HER performance compared to conventional commercial electrocatalysts, offering a new perspective for the design and development of high-performance bifunctional electrocatalysts for energy applications. This work not only advances the fundamental understanding of the material’s electrocatalytic mechanisms but also sets the stage for the next generation of energy conversion technologies.

Experimental

Experimental materials and reagents

All reagents were used as received without further purification. Deionized water was obtained from the Large Instrument Center at Liaoning Petrochemical University. Anhydrous ethanol (C2H5OH) and potassium hydroxide (KOH) were purchased from Liaoning Quanrui Reagent Co. Cobalt potassium cyanide (K3Co(CN)6) and pure cobalt were supplied by Alding Reagent Company. Hexahydrate nickel chloride (NiCl2·6H2O) was acquired from Shenyang Xinxi Reagent Factory. Sodium citrate (C6H5Na3O7) and ammonia solution (NH3·H2O) were sourced from Tianjin Hengxing Reagent Company.

Catalyst synthesis

Synthesis of CoNi prussian blue analogues (CoNi PBA)

Six millimoles (mmol) of NiCl₂ and twelve millimoles (mmol) of sodium citrate were dissolved in 80 mL of deionized water to create Solution A. Separately, five millimoles (mmol) of K3Co(CN)6 were dissolved in another 80 mL of deionized water to form Solution B. Solution B was then gradually added to Solution A under constant stirring. The mixture was stirred for 30 min and allowed to react for 24 h at room temperature. The resulting CoNi PBA was isolated by centrifugation, washed three times with deionized water, and freeze-dried.

Preparation of NiCoO2/NiCo@C

Twenty-five milligrams (mg) of the dried CoNi PBA precursor were placed in a porcelain boat and introduced into a tube furnace. The system was purged with nitrogen gas (N2) for 20 min to displace any air. The furnace temperature was then increased to 400 °C at a rate of 5 °C per minute and maintained at this temperature for 2 h. After the completion of the reaction, the furnace was allowed to cool to room temperature, and the black NiCoO2/NiCo@C product was collected. The same calcination procedure was applied at different temperatures (200 °C, 300 °C, and 500 °C) to obtain samples denoted as CoNi PBAs-200, CoNi PBAs-300, and CoNi PBAs-500, respectively.

Results and discussion

Figure 1 illustrates the preparation process flowchart for NiCoO2/NiCo@C. Initially, the XRD pattern of CoNi PBA, as shown in Figure S1, perfectly matches the standard diffraction pattern for CoNi PBA (JCPDS: 89-3738)25, validating the successful synthesis of the precursor.

Post calcination at 400 °C, the XRD spectra (Fig. 2) reveal the transformation of the precursor into a multi-component composite consisting of NiCoO2 (JCPDF: 10-0188)26 and NiCo metal (JCPDF: 15-0806 and 04-0850)27. The peaks at 2θ = 36.8°, 42.8°, 61.8° are correspond to the (111), (200) and (220) crystal planes of NiCoO2 respectively, confirming the successful synthesis of NiCoO2, while other peaks at 44° and 52° belong to the (111) and (200) crystal planes of Ni and Co metal peaks. Additionally, a distinct peak at approximately 26° correlates with amorphous carbon, underscoring the successful incorporation of carbon within the composite structure.

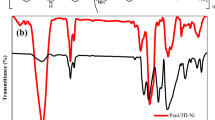

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) is conducted to analyze the elemental composition and valence states of the sample material. As shown in Fig. 3a, the XPS survey spectrum confirms the presence of Co, Ni, O, N, and C elements. As shown in Fig. 3b, the peaks located at 778.1 and 793.8 eV are respectively correlated with the Co 2p3/2 and Co 2p1/2 of Co0 28. Furthermore, the peaks at 781.7/798.2 eV are assigned to Co2+ and shake-up satellites29,30,31. In the deconvoluted Ni 2p region (as depicted in Fig. 3c), the 2p3/2 and 2p1/2 of Ni0 and Ni2+ ions emerge at 852.2/869.9 eV and 854.3/872.7 eV, respectively29,32,33. Meanwhile, their shake-up satellites are positioned at 859.4/878.1 eV. The O 1s spectrum (Fig. 3d) can be deconvoluted into three peaks corresponding to C–O (530.8 eV), M–O (529.1 eV) (M = Co or Ni), and O–H (527.6 eV), respectively29. The XPS results confirmed the successful formation of Co, CoO, Ni, and NiO through the heat treatment of CoNi PBA. The above results are in accordance with the outcomes of XRD analysis.

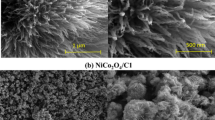

The morphology of the nano-catalytic materials synthesized in the experiment is characterized using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM). The SEM and TEM images of the NiCoO2/NiCo@C (Fig. 4a–c) clearly reveal the presence of tubular structures on the surface of NiCoO2/NiCo@C. The TEM image in Fig. 4c illustrates that some metal particles are encapsulated within carbon frameworks, while others are distributed within carbon nanotubes on the outer surface of the catalyst. The formation of carbon nanotubes enhances the electrical conductivity of the nanomaterials, thereby improving their electrochemical catalytic performance. The magnified HRTEM image (Fig. 4d) reveals that metallic metal particles are embedded within carbon frameworks (interspace of 0.36 nm)34, contributing to high structural stability and durability in an alkaline electrolyte. The lattice spacing of 0.177 nm corresponds to the (111) facet of CoNi35, while 0.213 nm corresponds to the (111) facet of NiCoO236. The elemental maps of NiCoO2/NiCo@C (Fig. 4e) indicate that Ni, Co, O, and N are uniformly distributed throughout the sample.

The OER performance of carbon-coated NiCoO₂/NiCo@C nanocatalysts is evaluated in an alkaline environment and compared to that of CoNi PBA, NiO, pure Co, Ni, and IrO₂. As shown in Fig. 5a, the polarization curve indicates that NiCoO₂/NiCo@C exhibits the highest catalytic activity for OER, achieving an overpotential of 329 mV at 10 mA cm−2. This value is significantly lower than those of CoNi PBA (390 mV), NiO (351 mV), IrO₂ (362 mV), Ni (393 mV), and Co (400 mV) in Fig. 5b as well as previously reported Co-based or Ni-based catalysts (Table S1). In addition, the overpotential of NiCoO₂/NiCo@C is only 392 mV at 100 mA cm−2 which is lower than CoNi PBA, NiO, IrO₂, Ni, and Co. The Tafel slopes (Fig. 5c) of NiCoO₂/NiCo@C, CoNi PBA, NiO, IrO₂, Ni, and Co are 61.88 mV dec−1, 69.64 mV dec−1, 65.37 mV dec−1, 67.9 mV dec−1, 80.2 mV dec−1 and 78.6 mV dec−1, respectively. Among all samples, the composite nano-catalyst NiCoO2/NiCo@C has the lowest Tafel slope and the highest OER catalytic kinetic properties. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) is performed and the fitted circuit of Nyquist plot in Figure S2. Figure 5d shows that NiCoO2/NiCo@C exhibits a smaller charge transfer resistance (Rct) of 3.5 Ω compared to NiO, Ni, and Co, thereby ensuring faster electron transfer. As shown in Fig. 5e and Figure S3, the Cdl value of NiCoO2/NiCo@C is 41.1 mF cm−2, which is higher than that of NiO (24.57 mF cm−2), CoNi PBA (15.77 mF cm−2), Ni (13.02 mF cm−2), and Co (14.77 mF cm−2). This indicates that NiCoO2/NiCo@C exposes more active sites during the catalytic reaction, thereby increasing the number of effective OER reactions. As shown in Fig. 5f, after 15 h of testing, NiCoO2/NiCo@C maintains a stable linear response under a current density of 13 mA cm−2, confirming its strong stability. Additionally, the LSV curve measured before and after 5000 CV cycles shows no significant increase in overpotential at 10 mA cm−2 compared to the first cycle, further demonstrating the catalyst’s durability. The excellent stability and durability arise from the protection provided by the 3D carbon network. The above results show the NiCoO2 and NiCo nanoparticles are incorporated into the heterojunction that boasts a large interface area and abundant exposed active sites and the NiCoO₂/NiCo heterojunction is further encapsulated by a stable and conductive three-dimensional (3D) graphitic carbon network37. Owing to the favorable interactions between NiCoO₂ and NiCo, modulated outstanding charge/mass transfer ability of the 3D carbon network22, NiCoO2/NiCo@C heterojunction shows high catalytic activity.

(a) LSV curves, (b) Overpotential required for j = 10 and 100 mA cm−2, (c) Tafel slope plots, (d) electrochemical impedance diagram, (e) Cdl to characterize the electrochemically active area for the four catalysts, (f) Electrochemical stability test for 5000 cycles of CV and i−t stability test for up to 15 h at a current density of 13 mA cm−2.

To investigate structural changes in CoNi PBAs calcined at different temperatures, TEM was used to examine the morphology of CoNi PBAs samples calcined at 200 °C, 300 °C, 400 °C, and 500 °C. The TEM images reveal that at a calcination temperature of 200 °C, the sample retains its cubic external structure with no significant changes (Figure S4a). When the temperature is increased to 300 °C, the cubic structure is still preserved; however, numerous internal pores become evident (Figure S4b). The presence of pores facilitates electrolyte penetration and gas expulsion. At 400 °C, the cubic structure of NiCoO2/NiCo@C disappears entirely, and nanotubular structures are observed on the surface (Figure S4c). The metal particles are embedded within the carbon framework, preventing agglomeration22. The formation of carbon nanotubes improves the electrical conductivity of the nanomaterials, thereby enhancing their electrochemical catalytic performance. In contrast, at 500 °C (Figure S4d), few tubular structures are formed, and significant agglomeration of metal particles occurs. In addition, the electrochemical OER performance of CoNi PBAs calcined at different temperatures is evaluated. The polarization curves of the electrocatalysts (Figure S5) indicate that the electrochemical activity is highest when the calcination temperature is 400 °C for OER (Figure S5a) and HER (Figure S5b), compared to catalysts calcined at other temperatures.

Similarly, the electrocatalytic hydrogen evolution properties of NiCoO2/NiCo@C, CoNi PBA, Pt/C, NiO, Ni, and pure Co are investigated under alkaline conditions. The polarization curve (Fig. 6a) shows that NiCoO2/NiCo@C has excellent catalytic activity of HER. When the current density is 10 mA cm−2, in Fig. 6b, the overpotential is 61.9 mV, which is better than CoNi PBA (140.9 mV), NiO (182.25 mV), Pt/C (94.51), Ni (281.3) and pure Co (260.0 mV). Tafel slope, as an important index to evaluate the performance of electrocatalysts, can reflect the rate control steps of electrocatalytic reactions and reveal the intrinsic activity mechanism of catalysts. As shown in Fig. 6c, the NiCoO2/NiCo@C has a lower Tafel slope of 42.6 mV dec−2 than that of CoNi PBA, Pt/C, NiO, Ni and pure Co, respectively. Figure 6d presents the EIS curves of each catalyst, illustrating the variation in charge transfer resistance during the HER process. Figure 6d shows that NiCoO2/NiCo@C exhibits a smaller charge transfer resistance (Rct) of 41.05 Ω compared to NiO, Ni, and Co, thereby ensuring faster electron transfer. Figure 6e shows the electrochemical Cdl values of NiCoO2/NiCo@C, CoNi PBA, NiO, Ni, and pure Co, which are 16.28 mF cm−2, 8.67 mF cm−2, 7.09 mF cm−2, 3.81 mF cm−2, and 5.48 mF cm−2, respectively. These results indicate that NiCoO2/NiCo@C possesses more active sites.

Conclusions

In this study, CoNi PBA is used as a precursor to prepare carbon-coated NiCoO₂/NiCo composite nanomaterials by sintering at 400 °C under N2. NiCoO₂ and NiCo nanoparticles are integrated into a heterojunction with a large interface area and numerous exposed active sites. Furthermore, the NiCoO₂/NiCo heterojunction is encapsulated by a stable and conductive three-dimensional (3D) graphitic carbon network. The morphology of the precursor CoNi PBA is affected by high temperature sintering. The catalyst exhibits excellent OER performance, with an overpotential of 329 mV and a Tafel slope of 61.88 mV dec−1 at a current density of 10 mA cm−2. Additionally, the material demonstrates good HER performance, achieving an overpotential of 61.9 mV at the same current density. The concepts, synthesis methods, and material properties described here offer valuable insights for the future development of high-efficiency OER and HER catalysts for commercial water splitting.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript and supplementary information files.

References

Patel, P. P. et al. Cobalt based nanostructured alloys: Versatile high performance robust hydrogen evolution reaction electro-catalysts for electrolytic and photo-electrochemical water splitting. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 42, 17049–17062 (2017).

Alagar, S., Gaur, A., Bera, C. & Bagchi, V. Rapid synthesis of a CuZn-MOF via controlled electrodeposition: manifesting enhanced overall electrocatalytic water splitting. Sustain. Energy Fuels 7, 3692–3700 (2023).

Xu, H., Shang, H., Wang, C. & Du, Y. Surface and interface engineering of noble-metal-free electrocatalysts for efficient overall water splitting. Coordination Chem. Rev. 418, 213374 (2020).

Zhang, Q., Duan, Z., Li, M. & Guan, J. Atomic cobalt catalysts for the oxygen evolution reaction. Chem. Commun. 56, 794–797 (2020).

Wen, H., Zhang, S., Yu, T., Yi, Z. & Guo, R. ZIF-67-based catalysts for oxygen evolution reaction. Nanoscale 13, 12058–12087 (2021).

Huang, C. et al. A hybrid Co NPs@CNT nanocomposite as highly efficient electrocatalyst for oxygen evolution reaction. Appl. Surf. Sci. 507, 145155 (2020).

Peng, X. Y., Huang, C., Dai, J. & Liu, Y. H. Uniform cobalt grafted on vanadium nitride as a high efficient oxygen evolution reaction catalyst. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 47, 4386–4393 (2022).

Anantharaj, S. et al. Recent trends and perspectives in electrochemical water splitting with an emphasis on sulphide, selenide, and phosphide catalysts of Fe Co, and Ni: A review. ACS Catal. 6, 8069–8097 (2016).

Li, R., Li, X., Liu, C., Ye, M., Yang, Q., Liu, Z., Xie, L., Yang, G. Enhanced electron transport through a nanoforest-like structure of CoNi nanoalloy@nitrogen-doped carbon nanotubes for highly efficient catalysis of overall water splitting. Appl. Surf. Sci. 517 (2020).

Huang, C. et al. Recent progress and perspective of cobalt-based catalysts for water splitting: design and nanoarchitectonics. Mater. Today Energy 23, 100911 (2022).

Yu, X. Y. et al. Formation of Ni–Co–MoS2 nanoboxes with enhanced electrocatalytic activity for hydrogen evolution. Adv. Mater. 28, 9006–9011 (2016).

Hu, F., Zhu, S., Chen, S., Li, Y., Ma, L., Wu, T., Zhang, Y., Wang, C., Liu, C., Yang, X., Song, L., Yang, X., Xiong, Y. Amorphous metallic NiFeP: A conductive bulk material achieving high activity for oxygen evolution reaction in both alkaline and acidic media. Adv. Mater. 29 (2017).

Pebley, A. C., Decolvenaere, E., Pollock, T. M. & Gordon, M. J. Oxygen evolution on Fe-doped NiO electrocatalysts deposited via microplasma. Nanoscale 9, 15070–15082 (2017).

Mondal, A., Paul, A., Srivastava, D. N. & Panda, A. B. NiO hollow microspheres as efficient bifunctional electrocatalysts for Overall Water-Splitting. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 43, 21665–21674 (2018).

QayoomMugheri, A. et al. Co3O4/NiO bifunctional electrocatalyst for water splitting. Electrochim. Acta 306, 9–17 (2019).

Sreekanth, T. V. M., Dillip, G. R., Wei, X., Yoo, K. & Kim, J. Binder free Ni/NiO electrocatalysts for urea oxidation reaction. Mater. Lett. 327, 133038 (2022).

Ito, Y. et al. One-step nanoporous structure formation using NiO nanoparticles: Pore size control and pore size dependence of hydrogen evolution reaction. Chem. Lett. 46, 267–270 (2017).

Huang, C. & Chu, P. K. Recommended practices and benchmarking of foam electrodes in water splitting. Trends Chem. 4, 1065–1077 (2022).

Wang, J. et al. Dominating role of Ni0 on the interface of Ni/NiO for enhanced hydrogen evolution reaction. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 9, 7139–7147 (2017).

Liu, Q. et al. Carbon nanotubes decorated with CoP nanocrystals: A highly active non-noble-metal nanohybrid electrocatalyst for hydrogen evolution. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 6710–6714 (2014).

Hou, Y. et al. Strongly coupled 3D hybrids of N-doped porous carbon nanosheet/CoNi alloy-encapsulated carbon nanotubes for enhanced electrocatalysis. Small 11, 5940–5948 (2015).

Huang, C., Wu, D., Qin, P., Ding, K., Pi, C., Ruan, Q., Song, H., Gao, B., Chen, H., Chu, P.K. Ultrafine Co nanodots embedded in N-doped carbon nanotubes grafted on hexagonal VN for highly efficient overall water splitting. Nano Energy, 73 (2020).

Xia, B., Yan, Y., Wang, X. & Lou, X. W. Recent progress on graphene-based hybrid electrocatalysts. Mater. Horiz. 1, 379–399 (2014).

Chen, W. et al. Polymeric graphene bulk materials with a 3D cross-linked monolithic graphene network. Adv. Mater. 31, 1802403 (2018).

Wang, S. et al. Controlled self-assembly of hollow core-shell FeMn/CoNi prussian blue analogs with boosted electrocatalytic activity. Small 18, 2203713 (2022).

Xu, X., Zhao, H., Zhou, J., Xue, R. & Gao, J. NiCoO2 flowers grown on the aligned-flakes coated Ni foam for application in hybrid energy storage. J. Power Sources 329, 238–246 (2016).

Yang, F. et al. Three-dimensional multi-channel structure NiCo alloy used for boosting efficient overall water splitting. Fuel 364, 131119 (2024).

Chen, H. et al. Elucidating the active phases of CoOx films on Au(111) in the CO oxidation reaction. Nat. Commun. 14, 6889 (2023).

Wang, D., Zhang, C., Hu, J., Zhuang, T. & Lv, Z. Nitriding-reduction fabrication of coralloid CoN/Ni/NiO for efficient electrocatalytic overall water splitting. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 655, 217–225 (2024).

Zan, L. et al. Electrodeposited cobalt nanosheets on smooth silver as a bifunctional catalyst for OER and ORR: in situ structural and catalytic characterization. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 14, 55458–55470 (2022).

Gaur, A. et al. Electronic redistribution through the interface of MnCo2O4–Ni3N nano-urchins prompts rapid In situ phase transformation for enhanced oxygen evolution reaction. Nanoscale 16, 10663–10674 (2024).

Rosmini, C. et al. Mesoporous Ce–Fe–Ni nanocomposites encapsulated in carbon-nanofibers: Synthesis, characterization and catalytic behavior in oxygen evolution reaction. Carbon 196, 186–202 (2022).

Tu, R. et al. Ni/NiO/C hollow microspheres fabricated by a mist-CVD process using ethanolamine: An efficient OER catalyst. New J. Chem. 48, 10133–10141 (2024).

Pi, C. et al. In situ formation of N-doped carbon-coated porous MoP nanowires: a highly efficient electrocatalyst for hydrogen evolution reaction in a wide pH range. Appl. Catal. B 263, 118358 (2020).

Shan, A. et al. Atomic-scaled surface engineering Ni-Pt nanoalloys towards enhanced catalytic efficiency for methanol oxidation reaction. Nano Res. 13, 3088–3097 (2020).

Su, C. et al. Controllable synthesis of crescent-shaped porous NiO nanoplates for conductometric ethanol gas sensors. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 296, 126642 (2019).

Huang, C. et al. Mo2C/VC heterojunction embedded in graphitic carbon network: An advanced electrocatalyst for hydrogen evolution. Nano Energy 60, 520–526 (2019).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the financial support by the Basic Scientific Research Project of the Education Department of Liaoning Province (JYTMS20231430), Scientific Research Project of the Education Department of Liaoning Province (Grant No. LJKMZ20220739) and the Research Foundation of Liaoning Petrochemical University (Grant No. 2019XJJL-022). These grants played a key role in the development of this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W.J. L. wrote the main manuscript, and Yajuan Chen analyzed data for the work, and S.Y. L. did the experiment and J. T. provided ideas and writing—reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, W., Chen, Y., Liu, S. et al. Enhanced electrocatalytic performance of carbon-coated NiCoO2/NiCo composites for efficient water splitting. Sci Rep 15, 12294 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96880-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96880-0

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Lithium-ion battery waste as a robust oxygen evolution reaction electrocatalyst for seawater splitting

Scientific Reports (2026)